Are All the Good Men Married?

Why do married men earn so much? Is it because the good men get married, or does marriage make men good?

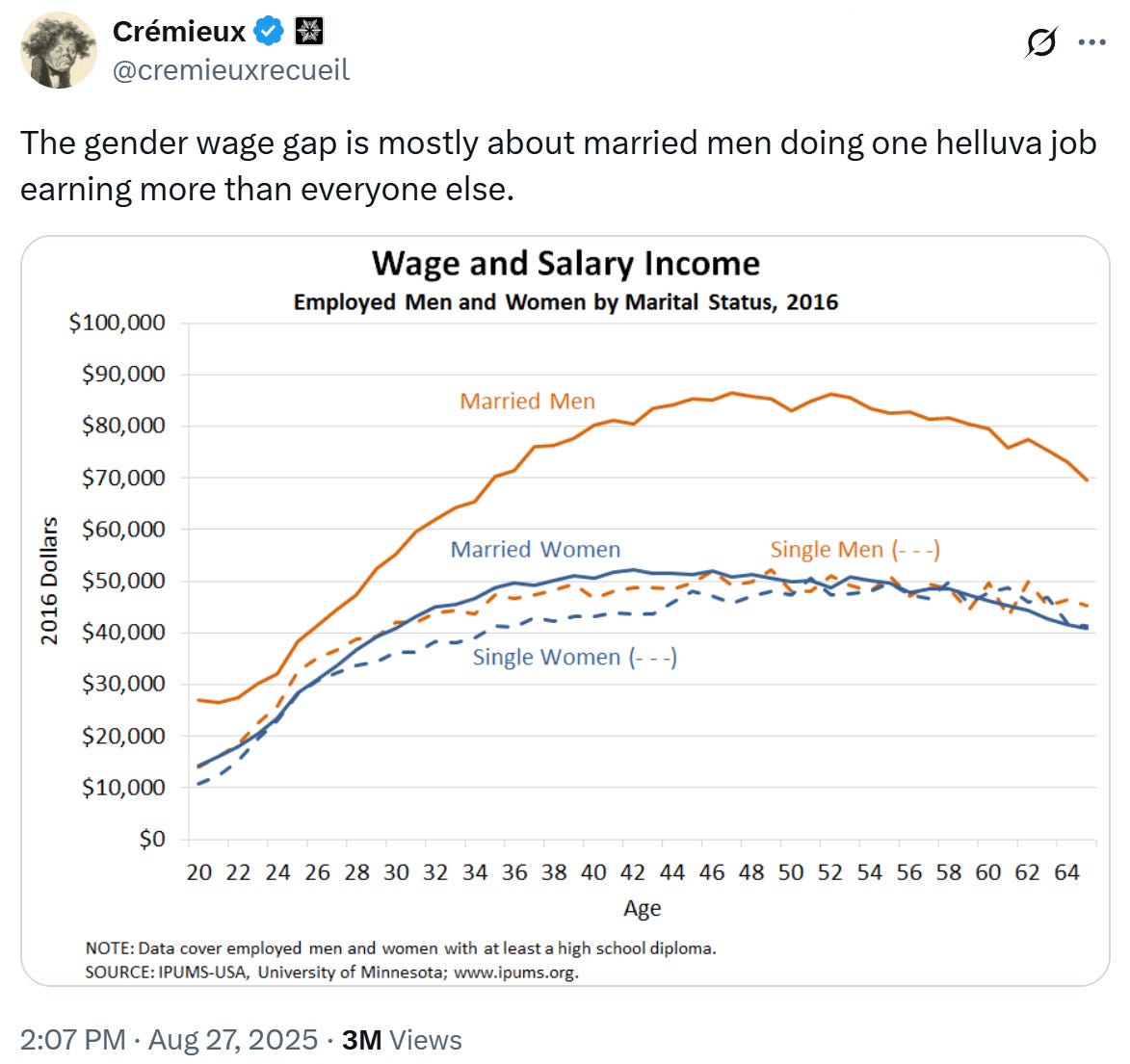

Men tend to earn more than women. Among employed people who completed high school, there’s not much of a wage gap until you look at married men versus everyone else. This finding was true going very far back, and it’s remained directionally true today. This considerable salary bump has come to be known as the Marriage Premium.

One interesting question is Why?

Is there a marriage premium because wives do all the housework so men have more time to spend on their jobs? Is there a marriage premium because marriage motivates men to work? Because childbirth motivates men to work? Is it because men anticipate marriage and get ready for it by growing their incomes? Is there a marriage premium because employers discriminate in favor of married men?

To figure out the answer, we have to define the predictions different hypotheses make. For example, the Anticipation hypothesis holds that men work to increase their wages because they expect to take on the husband role. The Reverse Causality hypothesis holds that men delay marriage until they’re able to meet their financial goals. The Spurious Association hypothesis contends that it’s all a coincidence because in the period where men are rapidly maturing into adults and moving up financially, they’re also likely to get married.

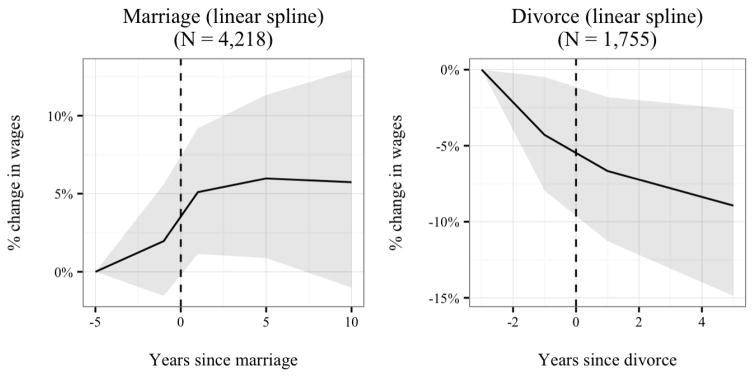

One of my favorite papers on this topic distinguished between these hypotheses using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY ‘79). Their dataset of choice provided them with the means to look at the wage effects of unexpected marriages, to investigate wages relative to marriage and age, and to determine whether the marriage premium was affected by subsequent divorce. Take a look at wage trajectories surrounding marriage and divorce:

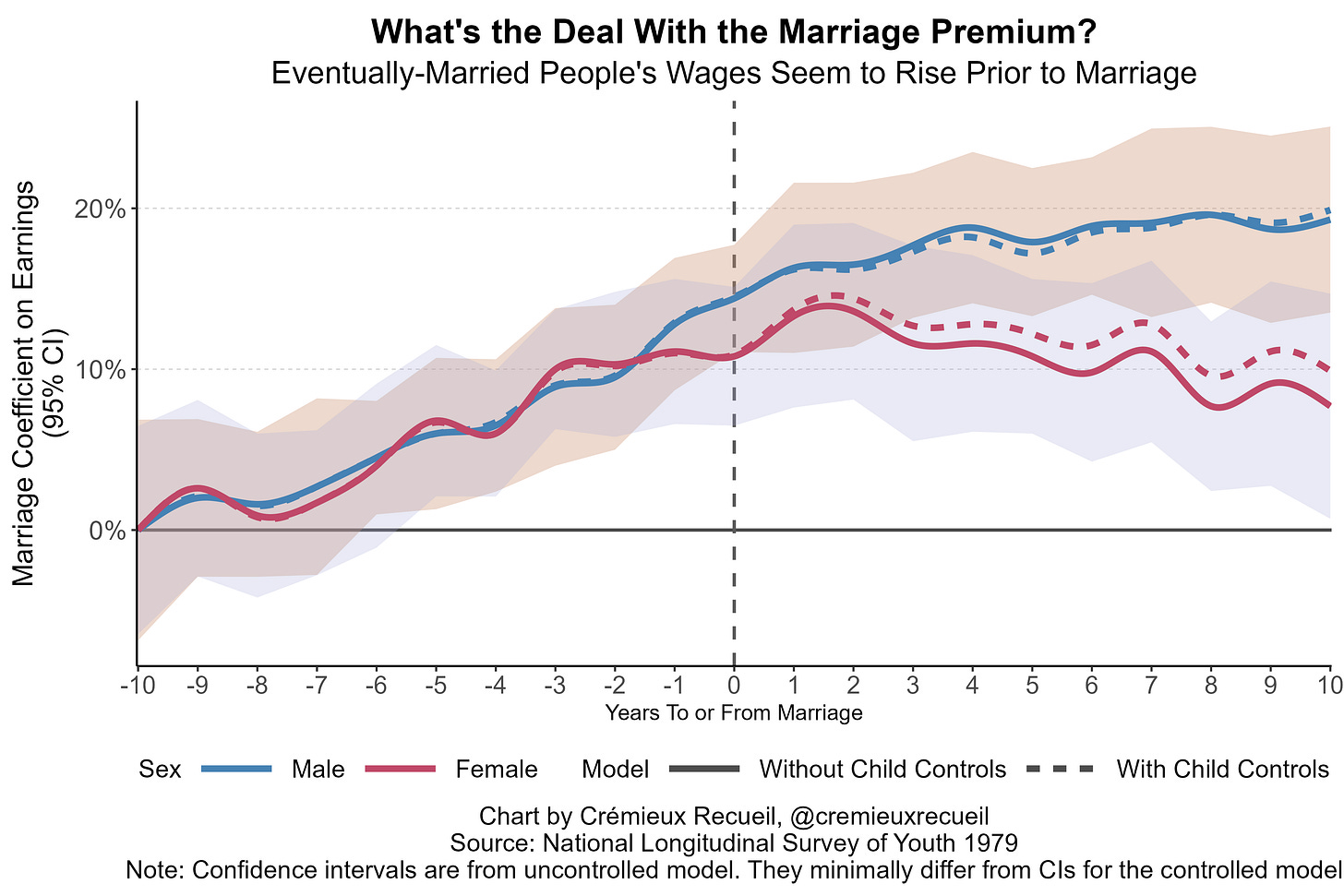

First, with marriage, people’s wages seem to start growing years ahead of the event itself. The increase is not statistically significant until after marriage happens in the authors’ specification, but I found this odd because, when I redid this, I had much smaller standard errors and did obtain a significant result. Others who used the same dataset and others have had similar findings. I’m going to replot the marriage data from the NLSY ‘79, but for a longer timeframe, with newer data releases included, using the method and controls from Dougherty (2005), and with results for both sexes.

This is an interesting finding for so many different reasons, and several of those reasons are theory-dependent. For example, what’s the marriage premium in this model? Is it the non-effect of marriage happening, or is it the rise leading up to marriage? For women, is it the decline that happens shortly after? (Which, I’ll add, is significantly hastened by childbirth.) For that matter, what does this say about the marriage premium as it’s typically estimated? The most common method is to use a fixed-effects model. Because that model includes single people who later marry as comparisons, it underestimates the marriage premium if we’re to count the rise leading up to marriage as part of it because people close to marriage are already earning the premium. I could keep talking about this, but I’ll digress in this section.

The Anticipation hypothesis predicts this result. It suggests wages will rise prior to marriage, so long as marriage is predicable. But, I’d caution against this view, because the increase begins long before people tend to be thinking about marriage with a particular person. Usually anticipation only applies about two years out, but in the NLSY ‘79, the rise is significant six years before marriage and it continues for a while after.

Luckily, the Anticipation hypothesis predicts other things. Those include a wage decline after divorce. On the subject of divorce, the authors noted that it “appears to be the consequence rather than cause of falling wages.” I can very significantly replicate this over a longer timeframe in their data, but though that is a controverted prediction of the Anticipation hypothesis—and a supported prediction of the Reverse Causality hypothesis—, it’s not definitive. Two things far more likely to be definitive are the effects of unexpected, shotgun marriages, and the existence of age-related moderation.

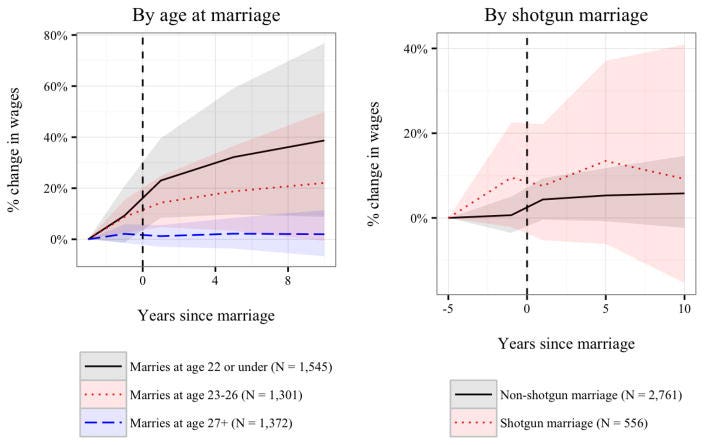

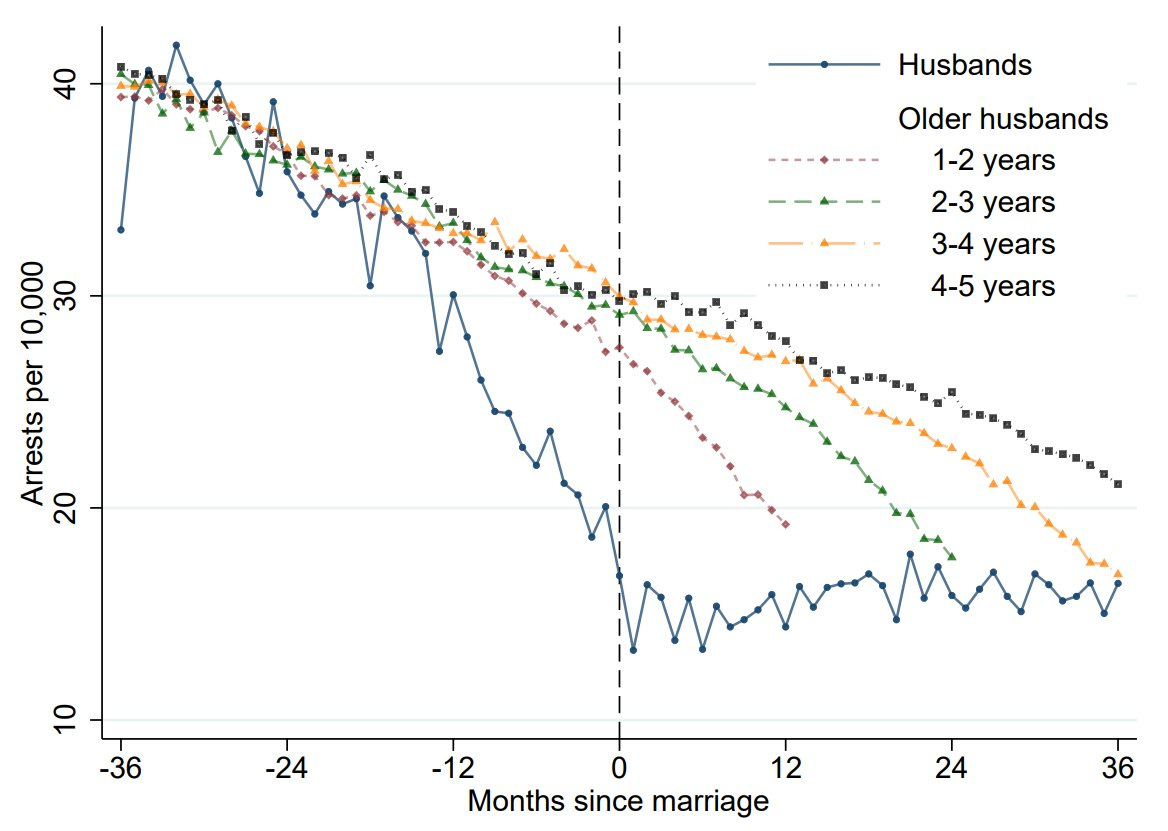

Anticipation predicts tiny premarital wage increases when the marriage is unexpected, and it predicts wage increases regardless of a person’s age, albeit perhaps only for first marriages. Reverse Causality predicts much the same, but the Spurious Association hypothesis does not. Findings like age-related moderation and similar wage increases regardless of marriage expectation fit best with a false marriage premium. Both of those things were observed by the authors, and this result is another one that can be replicated with tighter standard errors by redoing the analysis in the same dataset.

The finding that men who marry older don’t see any wage premium whatsoever is consistent with the idea that the marriage premium is a reflection of a maturation process rather than something prompted by marriage or the expectation of it. Similarly, the finding that shotgun marriages don’t vary from predictable marriages speaks against the Anticipation and Reverse Causality hypotheses. The hypothesis that the marriage premium is attributable to women taking over a man’s home duties is also contradicted by these results and by the observation of the premium primarily emerging prior to marriage itself, and long before it’s likely people are living together.

With the Anticipation, Reverse Causality, and Women’s Work hypotheses contradicted to different degrees, the authors progressed to addressing a number of other hypotheses. For example, they noted a lack of significant variation in marriage premiums by race, educational background, cognitive ability, wife’s employment status, gender role attitudes, or other expectation measures. They also computed individual marriage probabilities and found that, contrary to the predictions under a causal marriage premium, men with low probabilities who nevertheless married had, if anything, less favorable wage trajectories around marriage.

To top all of this off, the authors then proceeded to replicate this result in the NLSY’s later version, the NLSY ‘97:

We replicated our analyses on the NLSY97 cohort and, as in the NLSY79, found no evidence in favor of a causal marriage premium. Descriptively, as in the NLSY79, wages rise beginning prior to marriage and do not accelerate following marriage, while wages begin to decline prior to divorce. For this cohort, we do find significant variation in wage trajectories across specialization categories. Men with non-employed wives have the fastest wage growth one year before to one year after marriage, but then their wage growth changes significantly to a slight decline in the post-marriage period. This trajectory is the opposite of the prediction one would make based on a specialization argument.

To sum everything up, this report produced robust evidence that men marry when their earning power has already substantially risen, and they divorce after their wages have substantially fallen, with no implied causal effect of marriage on earnings. One can liken this to the picture observed with crime perpetration.

In perhaps my favorite paper on marriage and crime, Massenkoff and Rose documented that marriage is the culmination of a long-term reduction in crime perpetration. After marriage, the risk of committing a crime only declines slightly more, much like what happens with men’s wages increasing only slightly more after marriage. This is a long-term thing, where people mature prior to marriage, and that marks the time when they’ve truly become their developed, adult self.

Married Men are Mature Men

What we call the Marriage Premium appears to mostly be selection of matured men and women into marriage, not a causal effect of marriage. Earnings ramp up well before wedding and this increase doesn’t accelerate thereafter; earnings fall before divorce; shotgun marriages don’t differ from planned ones; and men who marry later show no premium. This pattern undermines theories built on anticipating marriage, high wages causing marriage, and wives’ housework allowing men to focus more on their careers.

Practically, claims that marriage raises men’s wages should be treated skeptically; marriage seems to coincide with and signal a completed or nearly-completed maturation process that is not universal, as opposed to causal effects of the institution. To the extent there may be a causal component to the marriage premium, it will be too small to detect in most datasets.

Thus, we can say the following: The marriage premium is primarily a matter of selection.

I mentioned above that the main study informing my conclusions is “one of” my favorites. There are many more papers that have dealt with the reasons behind the marriage premium, and I’ve compiled and elaborated on many of them below.