Are Girls Smarter Than Boys?

A new paper suggests the answer is 'yes', but it's not a very good paper

After more than a century of study, we actually don’t have an answer to the question of which sex tends to be smarter. We know with considerable certainty that men are more variable, but we don’t know if they also tend to be more or less capable. This isn’t for want of trying: lots of researchers have looked into this question and come to varying conclusions on the matter! A new Journal of Political Economy (JPE) paper by economists Harrison, Ross, and Swarthout (HRS) provides the following answer:

Contrary to received literature, women are more intelligent than men, compete when they should in risky settings, and are more literate.

Such a definitive answer deserves serious consideration. Unfortunately, on further inspection, it turns out that the authors’ conclusions are not warranted by their data and their methods are so poor that they would never be taken seriously by any qualified psychometrician. Their paper provides an example of peer review failing.

How Did They Make Their Conclusions?

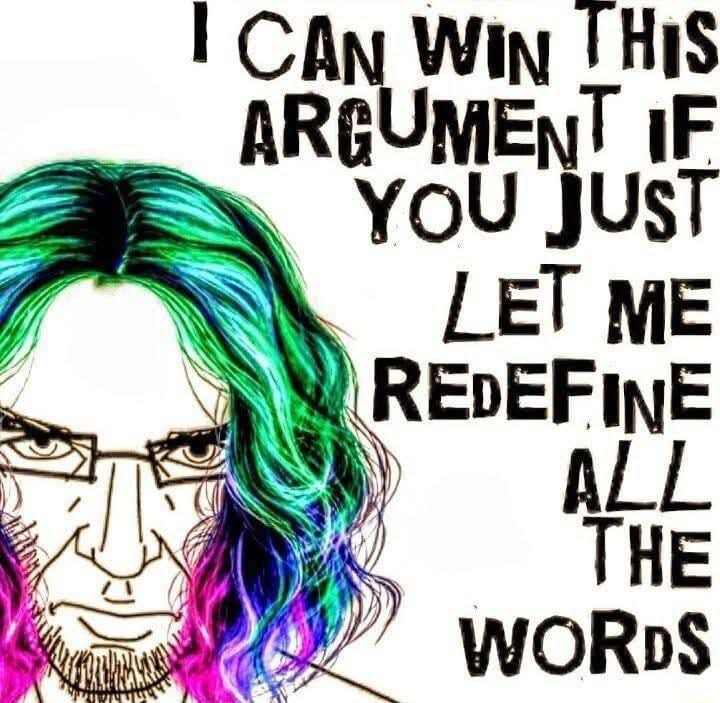

HRS were able to reach the conclusion that women are more intelligent than men by redefining intelligence in a way that favors women. They didn’t show that existing measurements were flawed or that their preferred definition of the trait is more consistent with how intelligence is generally understood than the standard definition is. Instead, HRS declared by fiat that they had a better measure and, by that measure, women are more intelligent.

This may sound like ‘the authors were just playing word games’, and that’s because they were! They measured something different from what people typically mean by ‘intelligence’, called it ‘intelligence’, and declared that women are ‘more intelligent’. By the same token, I could say women are taller if I define height as ‘height over weight’ rather than as, well, height. If I did, I hope most people would recognize that I’m just misusing words. Unfortunately, the peer reviewers and editors at the JPE did not.

Their work is less clever than it is annoying. But let’s be overly generous to HRS.

How Exactly Did They Make Their Conclusions?

HRS started from a reasonable enough observation: conventional intelligence tests record only whether a response is correct or incorrect, discarding potentially useful information about respondent confidence. When someone selects answer C on a multiple-choice question, we don’t know if they were certain it was right or if they thought it was slightly more likely than answer B, or even if they were just guessing.

This does seem like a genuine loss of information. Two people may both answer incorrectly, but one might have narrowed down the answers to two plausible options while the other had no idea what was going on. Traditional scoring, where you’re either right or wrong, conflates these failure modes. Similarly, two people might both answer a question correctly, but one might have been certain while the other was just lucky. Traditional scoring makes these into equivalent successes.

HRS proposed that this missing information—calibrated confidence—is itself a component of intelligent behavior. Knowing what you know, and knowing what you don’t know is certainly cognitively valuable; a person who recognizes the limits of their knowledge can seek help, defer judgments, or hedge better, whereas a person who is confidently wrong may produce catastrophe. From their perspective, intelligence measurement should reward not just rightness or wrongness, but calibration: he who reports uncertainty when he’s uncertain and confidence when he’s confident is more intelligent than he whose subjective confidence remains irrelevant.

To capture calibrated confidence, the authors adapted Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) to a new response format.

Traditionally, a test-taker looks at a matrix pattern with a missing element and picks among eight options to complete the pattern. If they’re correct, they earn a 1, and if they’re wrong, they earn a 0, with their total score being the count of correct responses. By contrast, in the adaptation, respondents allocate tokens among different responses according to their subjective beliefs about which is correct. If they’re certain response number five is correct, they can place all their tokens on it, and if they’re split between options five and three, they can split their tokens accordingly.

In the adaptation, respondents’ allocations are rewarded using a Quadratic Scoring Rule (QSR)—a proper scoring rule from decision theory—, which incentivizes truthful probability reports under risk neutrality. If a respondent places all their tokens on the correct answer, they earn $2, and if they hedge uniformly, they’re guaranteed $1.13, regardless of the correct answer. The authors call the resulting measure “efficiency” and define it as the fraction of the maximum possible earnings people achieve, thus rewarding accuracy (modal correctness) and calibration (appropriate confidence).

With traditional scoring, men outperform women, but with efficiency scoring, women outperform men. The authors interpreted this as evidence that women are smarter.

What’s the Problem?

Efficiency scoring changes what’s being measured. This is a fundamental issue; it means that the authors’ conclusions are only valid if what they’re measuring is closer to ‘intelligence’ than what the RAPM measures with standard scoring. This cannot be.

Efficiency scoring introduces variance from constructs that are distinct from intelligence. These constructs can be called metacognitive calibration, confidence, and risk preference, but as long as you understand them, the particular names are irrelevant.

The principal finding of intelligence research is the positive manifold: the observation that all valid measures of cognitive performance are positively correlated in the general population. The most common perspective holds that the positive manifold arises because each test loads on a common factor—g—plus test-specific factors. In matrix form, that comes out to:

where \lambda is the vector of g-loadings—regression betas on the general factor—, S contains the specific factor loadings, and \psi are the specific factors. The positive manifold appears because all elements of \lambda are positive, so higher g means higher performance on every test. Contrarily, consider what happens when you replace accuracy scoring with efficiency scoring: you introduce a new component into the measurement model! For simplicity, we’ll just add \kappa, for metacognitive calibration, and \rho, for the inverse of risk aversion. The efficiency score loads on these three latent factors, like so:

Risk-averse individuals (those high on \rho) hedge toward the floor. On easy items, this hurts them because they tend to leave money on the table by not concentrating their tokens on correct answers. On hard items, this helps them because they secure the floor winnings of $1.13 instead of gambling for scraps. This means that \delta_j is negative for easy items and positive for hard items.

Consider what this means for the covariance structure of the items. For two items, j and k, with different difficulties:

If j is easy and k is hard, then \delta_j<0 and \delta_k>0, so \delta_j\delta_k<0. The risk preference component contributes negative covariance between easy and hard items. This works against the positive manifold! It means the authors have introduced a factor that makes performance on easy items negatively correlated with performance on hard items, conditional on g. The empirical consequence of this is that the factor structure of efficiency scores should be messier than the factor structure of accuracy scores. You might see…

Lower overall loadings on the general factor

The emergency of spurious difficulty factors

Negative residual correlations between item pairs at opposite ends of the difficulty spectrum—a violation of the local independence assumption of latent variable models

If Harrison et al. had computed a correlation matrix of item-level efficiency scores and extracted factors, I would predict they’d find worse fit to a unidimensional model than they would find with accuracy scores. Moreover, they would not find something consistent with the key findings of intelligence research, but instead, with a novel understanding of intelligence as a behavioral combination of multiple constructs, including what is typically considered to be intelligence. This is clearly absurd.

What Should They Have Done Instead?

Testing which sex is smarter is straightforward and simple. All you have to do is administer a large, diverse test battery, score the answers as right or wrong, and then fit an appropriate latent variable model if such a model holds between the sexes (meaning that there’s no bias). Then, check which sex has a higher level of g. That’s all!

In the absence of psychometric bias, the authors cannot claim that there is any important measurement issue with typical testing, aside from, say, a given battery being weighted towards content that favors one or the other sex. All they can do is quibble about intelligence being something different from what the field of intelligence research has understood it as. They’re stuck arguing that it’s not one thing that can be measured, but multiple things that come together from different traits, one of which is what the relevant field considers intelligence to be, and the others of which are clearly measured with bias across demographics like sex and race.

On its own, this should be considered devastating: HRS are just playing word games and they’ve failed to justify their conclusions from playing those games. They provided no reasons to think intelligence needs to be redefined, let alone as they’ve chosen to define it. As I’ll discuss below, they don’t have room to play this game at all. Their preferred definition of intelligence is simply unjustifiable—full-stop.