Black Economic Progress After Slavery

An exploration of new empirical work on the topic

This post is long, but the conclusion is short. A recent paper provided data that indicated the effect of slavery on the socioeconomic status of Black Americans was now minimal. To understand how I came to that conclusion, read on.

Economist duo Althoff & Reichardt have produced what many are calling a tour de force, a magnum opus, and a variety of other laudatory loanwords for their new prepublication paper Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery. They used extensive linked Census and administrative records from 1850 to 2000 to detail the impacts of slavery on the socioeconomic progress of Black Americans through many generations. In their own words

Black families who were enslaved until 1865 continue to have considerably lower socioeconomic status today [compared to White families and Black families whose ancestors were freed prior to the Emancipation Proclamation]…. This persistence is entirely driven by post-slavery oppression under Jim Crow [with] limited access to human capital as a key mechanism.

The strength of this finding is unambiguous. By exploiting variation in the exposure to slavery by contrasting Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved for different amounts of time, we should be able to assess the direct impact of slavery on subsequent generations’ socioeconomic attainments. This important observation can help to unravel the mystery of precisely what legacy slavery has left us. As Americans might suspect, the legacy of slavery was substantial. The first glimpse of this comes in Figure 3:

Between 1870 and 1940, the gap between the descendants of freedmen and slaves substantially closed for literacy, but it only closed a bit when it comes to occupational skill. In both cases, the gap closure was significant. In Table 1, the Free-Enslaved gaps were presented numerically for education, income, homeownership, and home values. By 1940, the gap in education comparing the descendants of freedmen and the enslaved was 1.59 years of education (versus a mean of 5.99 years for a combined sample of descendants of freed and enslaved Blacks), $145.92 of income (versus $381.20), 7.24% lower rates of homeownership (versus 29.25%), and $694.69 lower home values (versus $1,371.95). The authors provided the means for the whole group along with the numbers of freedmen and slave descendants included in that and the difference in their means. With that information, we can use a bit of algebra to solve for the means for freedman and enslaved descendants. The mean number of years of education received by slave descendants was 5.91 versus 7.50 for the descendants of freedman; slave descendant income was $373.55 versus $519.47; homeownership rates were 28.87% versus 36.11%; and home values were $1327.29 versus $2021.98. Given the values for the descendants of the enslaved are so close to the total mean values, readers may correctly infer that the sample featured far more enslaved descendants than descendants of freedmen. In the United States at large, there were four million slaves in 1860, compared with .4 million freedmen, for an order of magnitude difference. In this dataset, the difference in their proportions is usually twice that.

Table 2 extended the analysis all the way to the year 2000, showing that descendants of the enslaved were 3.02% less likely to finish high school, 2.45% less likely to finish college, that they earned $4,795.93 lower incomes, and that their homes were valued at $15,755.30 less than the homes of freedmen descendants. In the year 1940, the descendants of the enslaved had 72% of the income of the descendants of freedmen and their homes were worth 66% as much; in 2000, their incomes were 86% as large and their homes were worth 82% as much.

At a first glance, it might appear that 60 years of progress wasn’t worth very much. This conclusion certainly makes sense if the only thing differentiating the descendants of freedmen and the enslaved was their experience with slavery. But, as the authors showed, location trumped slavery experience. The apparent effect of a longer time under slavery was actually the effect of living in poorer states and counties, with stronger Jim Crow laws.

Exposure to state-specific factors accounts for virtually all of the Free-Enslaved gap after 1940. […]

With Black families freed in the Lower South faring so much worse than families freed elsewhere, it may seem puzzling why so few of them left the region, while large fractions of those freed in the Upper South migrated to the North. Institutional and economic factors partly resolve this puzzle. First, Jim Crow directly targeted the geographic mobility of Black people. Enticement laws and contract enforcement laws limited Black workers’ ability to terminate their employment contracts; Vagrancy laws essentially criminalized not having a job; Emigrant-agent laws prevented employers from seeking workers from other states. Second, moving to the north was costly, especially from the Lower South. […] Even for those Black families who did migrate to the North, opportunities there were elusive.

To prove the importance of geography, the authors provided what I consider to be one of the most informative figures in the paper.

In other words, accounting for the state the descendants of freedmen and slaves were located in, the two groups were socioeconomically statistically indistinguishable. The authors computed the lower-bounds for geography’s effect and found that it explained at least 67% of the literacy gap and at least 50% of the gap in years of education. In their preferred models, geography respectively explained 95% and 75% of those gaps. As a further proof of this, the effect of location on years of education was estimated for groups whose ancestors spent varying amounts of time in the locations they were freed in rather than places they migrated to after manumission. When almost all of a person’s family’s time after being freed was spent where they were freed, geography was very strong (β = -.85); when about two-thirds of that time was spent there, the effect was attenuated somewhat (β = -.58); when about two-thirds of the time was spent elsewhere, the effect was even smaller (β = -.28); and when almost all of their time was spent outside of where they were freed, the effect was nonexistent (β = .03). Moreover, the effects of different locations are nearly identical between the descendants of freedmen and slaves, but they are unrelated to outcomes for Whites, and this is unambiguous:

The authors then showed that the geographic factors had to do with Jim Crow by showing that border discontinuities where borders demarcated the extent of Jim Crow laws mirrored state-level differences, suggesting that all of the geographic effects could be attributed to Jim Crow. Importantly, Jim Crow didn’t seen to matter for White Americans, except for White land-owning elites, who actually benefitted from it. We are even provided evidence about the characteristics of Jim Crow laws, little-seen elsewhere:

The number of different Jim Crow laws is important, because the authors hypothesized that the primary mechanism through which Jim Crow impeded Black socioeconomic progress. The Rosenwald schooling initiative, where thousands of schools were established to educate Blacks in the south, provides some strong evidence that this might have been the case, at least to some degree. Where Rosenwald schools cropped up, Blacks were able to achieve more years of education, and remarkably, by the year 2000, Rosenwald schools still had significant impacts on income, college degree attainment, and housing values, but these effects were absent for movers. And finally, states’ effects on Black socioeconomic progress in 1940 were comparable to their effects in 2000.

Summary out of the way, the big conclusion from the study should be that there is no legacy of slavery. This figure makes that clear

By looking at the difference between within-county enslaved-freedman differences and the same differences between counties, it’s clear that slavery did not leave a lasting impact on subsequent generations. The differences were just due to things that varied between counties. Nothing significant remained comparing either group of descendants within the same places. This conclusion remained true looking at outcomes in the year 2000, too.

Contrarily, the authors wanted to strengthen their conclusions by noting how this pattern differed for Whites. To do this, they compared the freed-enslaved gap to the gap found between the descendants of Whites who had no physical or human capital in 1870 to the descendants of ones who did in the same year. In socioeconomic terms, minus discrimination and slavery trauma, those groups could be considered equivalent. Their conclusion was as follows

In only 30 years, the gap in literacy between those two groups of white Americans rapidly shrunk from over 90 percentage points to less than 10 (from twice the Free-Enslaved gap in 1870 to half the Free-Enslaved gap in 1900). The homeownership gap for the two groups of white Americans was similar to the respective Free-Enslaved gap in 1870 but closed by 1900—while the Free-Enslaved changed very little until then. Thus, consistent with racial disparities in intergenerational mobility throughout US history, we find that the Free-Enslaved gap narrowed far more slowly over this period than comparable gaps among white Americans.

But this conclusion was too hasty, and the graph of this White American benchmark shows why

If it’s unclear, the massive convergence between Whites whose ancestors lacked physical or human capital in 1870 and 1940 was due virtually entirely to the first jump from 1870, and that is why it exists in the first place. The gap is definitional: the group without any physical or human capital could only move up, and up they moved, so the line was steeper than it was for the group of Blacks it was being compared to, but only for the unfair comparison in the first period. The comparison is unfair precisely because it was defined as such. If we define individuals in the modern census by having zero assets, we will be unsurprised to see a rapid increase in assets in the next census because unlike picking a more natural group in the population, we have concocted one that can only evolve in one direction. Exampling this, in the Survey of Income and Program Participation, individuals in each wave who have zero or negative total household net worth have much greater increases in the next wave compared to the general rate of increase. The Black group, on the other hand, had roughly five years to build up from near-zero outcomes and is not defined in 1870 by its lack of assets, and thus its soon to be resolved precarity. Those five intervening years may not sound like much, but the Civil War induced labor shortages in the White population, and times of recovery and economic reorganization are often great for economic equality, since people need to do anything - including employing people of other races - to ensure their businesses survive. This benchmark does not justify the authors’ conclusions about it. But the post-1870 data is still useful, but I think it’s a whole lot more useful if we combine it with the freed versus enslaved gaps. To do this, I extracted the data from their images.

And if we subset to post-1880 to eliminate that nasty artefactual jump for clarity:

Benchmark homeownership catch-up is similar to the convergence between freed and enslaved Blacks within counties; literacy convergence was like the within-county convergence, but a bit less drastic than the between-county convergence; occupational skill convergence was less than that for within- or between-county Black convergence; income convergence was less than the within-county convergence, and was comparable to the between-county Black convergence up to 1940, but declined somewhat in that year. The reason for that decline may have to do with the fact that Blacks lived disproportionately in the south and the south was disproportionately affected by the Great Depression than much of the rest of the country. Part of this might have had to do with the south’s reserve bank districts being less activist than the rest of the country, which had a smaller Black population. There is an intra-southern example of how this could have come about. Mississippi was divided between two federal reserve districts, the Atlanta and St. Louis ones, and the Atlanta district was far more active than St. Louis, resulting in fewer bank failures and a smaller decline in physical output. Regardless of how it came about, it was unlikely to be more than a blip because World War II-induced labor shortages greatly enhanced the socioeconomic positions of Blacks.

But theorizing about the benchmark is unnecessary when we can do significance tests. As in Gregory Clark’s research, we should compare the slopes of convergence. The first step is to assess the base model: is the slope for each status measure by year significant, irrespective of group? Yes. Whether we cut off the first measurement year or not, the slope is very significant (t’s = 4.529 without the cutoff and 3.995 with it). Next, we need to assess whether slopes differed between outcomes. If they did for any outcome, subsequent models will need to separate them. As it turns out, they did for literacy versus the reference outcome, homeownership (t’s = -3.109 and -3.147), but slopes did not differ for income or occupational skill (all p’s > .5). And finally, for each outcome in no particular order, did the group - between-counties, within-counties, or Whites without capital - affect the slopes?

The reference category for testing these group interactions for each outcome is the between-counties group. In the long data, there were no significant interactions for literacy, but removing the first year (i.e., making short data), there were significant differences such that both Whites and within-counties converged significantly more slowly than between-counties (t’s = -4.592 and -4.852, respectively), although the convergence rates for Whites and within-counties did not significantly differ from one another. For income, there were no significant differences in the full data, and in the long data Whites converged slightly faster than between-counties but not differently than within-counties. This significant effect was due to the 1940 decline, and keeping trend, it was not significant, and removing it, it wasn’t either. For occupational skill, in the long data, Whites converged significantly more quickly than between-counties, but not differently than within-counties (only when using a one-tailed test; this is a nonsignificant difference when two-tailed). This significant effect disappeared in the short data, and it only appeared in the first place because it was built in by how the White sample was constructed. And finally, in the long data, Whites converged in homeownership rates more rapidly than between-counties but not within-counties, and like occupational skill, this was due to it being baked into the data. In the short data, Whites converged significantly more slowly than within but not between-counties, who converged significantly more rapidly (only one-tailed).

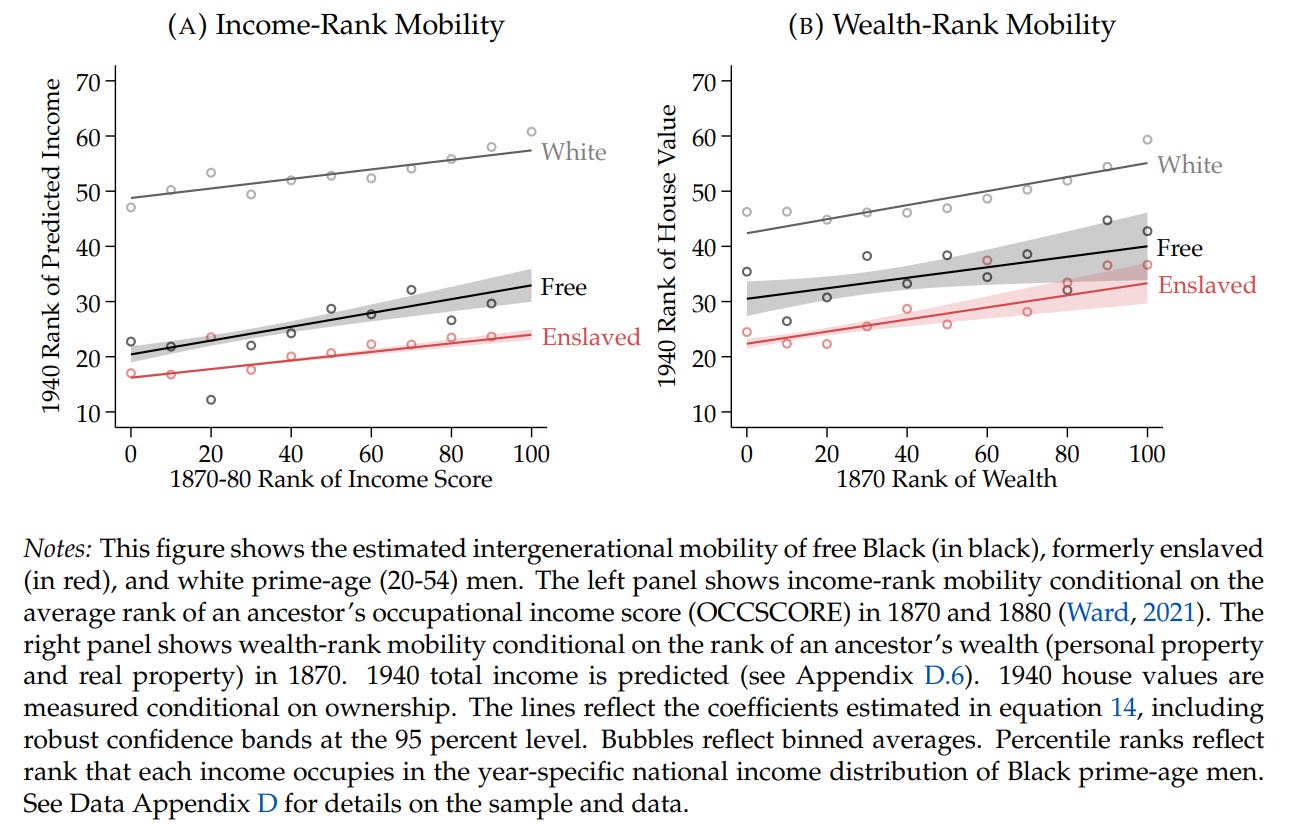

Overall, benchmark rates of convergence indicated that there was nothing unique about the convergence of the descendants of Whites without physical or social capital with the descendants of Whites who did have physical or social capital at the outset of the benchmark group’s creation. The rates did not differ from the rates for Blacks, and when they appeared to, this was artefactual (i.e., because the White group was defined to only be able to increase in some measures or because of an unexpected, and unkept trend break for Black incomes) or went in the opposite direction (i.e., between-counties Black literacy convergence was more rapid). We were also provided another benchmark of sorts, in the form of Income-Rank and Wealth-Rank mobility figures for the descendants of freed and enslaved Blacks, and Whites, and those indicate no significant difference in slopes for Whites and enslaved descendants for income mobility, and for anyone when it comes to wealth rank mobility.

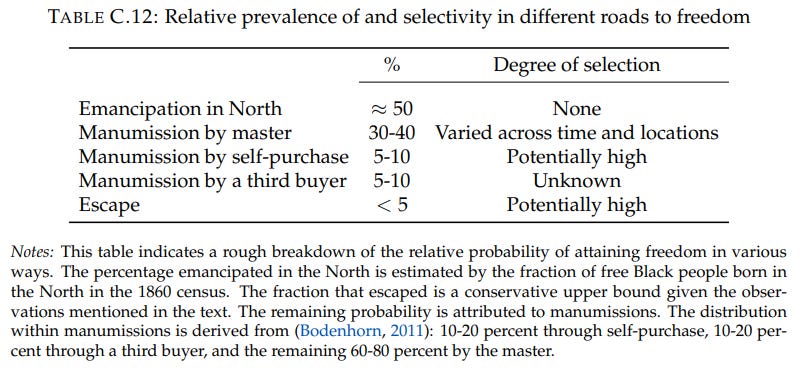

Besides the benchmark, there’s another issue with the study: misestimated magnitudes. Thanks to selection into geographic units, the estimated sizes of the effects of geography are far too large. The effect of geography is almost certainly not absent, but it is overestimated, and the authors know this could be the case because they devoted a section of their appendix to dealing with it. In section C, they dealt with selection from five different sources, given in Table C.12.

The sources and inferences that led to these conclusions are in error. Each of these points can be addressed in brief. Firstly, escape. As noted, the likelihood of selection via escape is high. This is because escape is difficult and things that are difficult are rarely undertaken by the physically and mentally infirm; instead, they are more likely to be done by the physically and mentally superb. But, as noted by the authors, the part of the free population who were escapees and their descendants was small, and likely considerably less than 5% of the total freed Black population. The estimates they presented included 1850 and 1860 census survey answers indicating fewer than 2,000 freedmen who were runaways, Dittmar & Naidu’s estimate of roughly 8,000 attained through linking runaway slave advertisements and slaveowner records, and a Pennsylvania census in which 2 of the 314 Blacks who were not born free were identified as runaways. Out of a population of approximately 400,000, those are runaway percentages of .5%, 2%, and .64%, respectively. As noted by Ira Berlin, “[runaways] had always been more skilled, sophisticated, and aggressive than the mass of slaves”. Despite its likely selectivity, due to their small population share, the impact of runaway slaves on the selectivity of the freedman population was necessarily small, even if being a runaway selected very strongly for human capital.

Manumission by self-purchase and third buyers are intimately linked. Self-purchase involved obtaining enough extra spending money to pay off one’s master for freedom. Self-purchasing implied a huge amount about a person’s human capital. It meant they were industrious, at a minimum, and in addition, quite likely highly capable with that industry. Moreover, they had to be convincing enough to their masters to convince them to even let them purchase themselves. As examples, consider the cases of Israel Campbell and Venture Smith. Israel Campbell did not self-purchase, but instead, escaped slavery and made his way to Canada. However, his autobiography provides extensive details of the effort he could put in to earn more money in his time as a slave. He regularly attempted to exceed the quotas set for him so he could earn extra money, and he was even able to spend that money on a dress for his bride and a suit for himself. Venture Smith began his own autobiography eloquently

I was born at Dukandarra, in Guinea, about the year 1729. My father's name was Saungm Furro, Prince of the Tribe of Dukandarra. My father had three wives. Polygamy was not uncommon in that country, especially among the rich, as every man was allowed to keep as many wives as he could maintain. By his first wife he had three children. The eldest of them was myself, named by my father Broteer. The other two were named Cundazo and Soozaduka. My father had two children by his second wife, and one by his third. I descended from a very large, tall and stout race of beings, much larger than the generality of people in other parts of the globe, being commonly considerably above six feet in height, and in every way well proportioned.

The man described in this paragraph was enslaved and brought to America, but would go on to purchase his own freedom. After acquiring his own freedom, he would work tirelessly, scrimping and saving, buying nothing for himself, to gain the money to eventually purchase his two sons, Solomon and Cuff, for $200 a piece. He then purchased a Black man he didn’t know simply to free the man, and he even provided him with $60 (technically pounds, but I am treating them as dollars), but the man ran away from him. After some time, one of Venture’s sons took a job on a whaling boat but on that boat, died of scurvy, and Venture was never compensated for the pay he was owed for his son’s efforts on that voyage. Venture then bought a sloop and began to use it successfully, earning enough to purchase his wife Meg. After that, he became a watermelon grower, bought two slaves and released them, and then bought his daughter. All said and done, he earned thousands over the years, and managed to free multiple slaves, family and otherwise.

Both of these men were able to do a lot whilst slaves and a great deal after earning their freedom. The gumption required to free yourself from slavery by self-purchase of running away is immense, and self-purchase specifically was undoubtedly very selective. The purchase by a third buyer was also selective in several ways. Few people would buy others out of good will to free them; they would generally buy people with purpose - people who seemed like they could be used. Venture bought men to free them, and had his troubles for it, but he also hired one man who was a comb-maker (who did end up robbing him). To the extent a purchase is related to a person’s ability to work, it will be selective. To the extent a purchase of family reflects assortative mating, it will be selective. This is a likely scenario, even for slaves. It’s almost unfathomable to imagine, say, Einstein, electing to marry a woman with an IQ of 63. At the genetic level, there is considerable assortative mating for an “education” polygenic score, even when the phenotypic education correlation between spouses is low in the modern day. Clearly people can pick up on the nexus of socioeconomic status-enhancing traits affected by these genes. In preindustrial Britain, when environmental quality was basically nil for most Britons, there was still strong assortative mating. Even if there is no assortative mating, because this is an intergenerational analysis, we have to recognize that the traits of children will tend to be correlated with their parents, including the one who purchased their freedom.

Through these routes, being purchased for freedom should be considered highly selective in general, as most purchases of others for this purpose were purchases of family, and to be able to afford doing this implies a considerable level of ability and industry. The extent of self-purchase was also rather extreme, as opposed to the low 5 - 10% level proposed in the original paper. As an example, in Cincinnati in 1839, 42% of freedmen had purchased their own freedom. Because intergenerational transmission of the qualities that led to self-purchase will be transmitted in part genetically, this should be a very strong source of concern.

Manumission by masters was highly selective in general for several reasons. Firstly, due to the structure of American poor laws, many states banned manumissions by masters with limited exceptions that tended to revolve around demonstration of a slave’s merit. Masters who wished to free their slaves had to support them if they became charges of the state, but they could also pursue a certificate that alleged the slave was of a high enough quality to avoid personal liability for that slave’s status after being freed. Without that certificate, they may have to provide a bond for the slave’s manumission, and without proof of the slave’s good character, they may not have qualified for an exception to the rules stating that they had to provide transportation outside of the state they were freed in. These rules were often violated and violations were often punished, but they were still in place and still had an effect, making manumission by one’s master, even without self-purchase, more selective. Importantly, the authors knew about this source of bias because it was mentioned in a source they cite, Bodenhorn (2010).

Bodenhorn contains all the relevant information we need to understand the other major source of bias lies in who masters chose to free: they disproportionately freed mixed-race people (i.e., “mulattoes”, as they were then known, and “half-White”, as they will be referred to here, except in quotation), and these tended - as many, including Ira Berlin observed - to be their own children. There are three reasons this generates a substantial bias.

The children of slaveowners are the children of relatively high-status individuals.

Compared to the children of slaves alone, the children of slaveowners have lighter skin and more European appearances.

Compared to the children of slaves alone, children of slaveowners have more European-like cognitive traits.

The first reason provides direct and indirect status to people freed by masters, because they had a chance to receive a bequest, and they inherited the genes of the master freeing them. There is considerable heritability for hourly, occupational, annual, and lifetime earnings, and wealth (at least in the modern day) is approximately income. Moreover, it is known that when the Civil War ended, slave owners lost their socioeconomic status, but they also regained it rapidly, despite not having access to slave capital. The explanation provided for this in the linked paper is that “Sons of wealthy fathers were able to bounce back through the transmission of other advantages, which may have been access to social networks.” And one might conclude, then, that sons of slaveowners could hold this source of advantage; their fathers freed them, they might as well socially favor them too, right? But this explanation was completely unevidenced, and the authors provided numerous other examples of status persistence despite that explanation not being viable at all for those. Parsimony demands we consider these examples to be explicable similarly, rather than by a totally unevidenced mechanism. To that end, they rule out social networks and rule in the genetic transmission of status. Lets briefly review. First, quoting the paper:

Although every historical episode is specific, the loss of wealth of Southern slaveholders rivaled the losses of wealth households in Germany after World War I, in the United States, the United Kingdom and France during the Great Depression, and even Chinese and Russian elites after the Communist revolutions. We find that, in the case of the U.S. South, such large wealth losses at the very top can be temporary, resulting in recovery within a single generation.

The paper cited Gregory Clark’s The Son Also Rises, an extensive, well-documented book published in 2014, which showed that there seemed to be evidence consistent with a “law of mobility” across the entire world. People of high status had genotypes that apparently disposed them to achieving high status even after radical upheavals of the social and economic order. Contrarily, people of low status had genotypes that disposed them to achieving low status even after radical upheavals of the social and economic order. Over many generations, status was persistent within lineages, and it showed slow regression to the mean, for both the rich and the poor.

This pattern was observed in the Indian subcontinent, where status persistence was comparable for the Hindus, Muslims, scheduled caste elites, and the Kulin Brahmin. Under British colonialism, status persistence was as strong as it was after, all the way up to 2011. The lone exception was the scheduled caste group. This group was arbitrarily defined by the British, and it included many prosperous, high-status groups within it. After the advent of the reservation system and the end of the caste system as a matter that suppressed their status artificially, they skyrocketed in status, but the groups who no longer enjoyed official privileges and had become artificially crowded out by the reservation system were unaltered. The non-zero sum nature of status was also made apparent due to a change in the composition of the Kulin Brahmin, where emigration after independence led to a reduction in average status in stayers of the same groups, but among a group that didn’t leave, there was no change in status.

In Japan, the Samurai were a class with the exclusive right to surnames and the Kazoku were the merger of the kuge and daimyo classes. Both enjoyed substantial privilege, but in the case of the Samurai, the Han and Tokugawa privileges they held were wiped out by decree, and sometimes by force. Various Samurai groups led several rebellions against the Meiji government, all unsuccessful, and all resulting in loss of Samurai life and status. From the Hagi, to Saga, to Shinpūren, to Akizuki, to the Boshin War, through to the legendary Satsuma Rebellion that culminated in the Battle of Shiroyama, the Samurai were taking hits left and right, and by the end of it, their station had been effectively eliminated. They were not even the only class who could have surnames and participate in politics anymore, and they frequently faced rustication for even petty misdemeanors. Despite this, the descendants of the Samurai - and the Kazoku - still maintain high status in Japan. And even more importantly for eliminating social networks as an explanation, Samurai and Kazoku descendants have similarly high status in America. Even more important than that is that the Kazoku were more downwardly mobile across generations than the Samurai. The reason lies in that the Samurai were a long-standing class, and the Kazoku were only 42% hereditary, with the rest being people awarded the rank as recognition of their meritorious conduct. This singular exemplar of merit made for a single generation with greater notability than the Samurai of the same generation, because it was selection on a single generation’s notability; underlying status in that generation was poorly tagged because it was assessed based on one thing, so the underlying status regressed to the mean faster across generations. But this also reinforces the point about kin networks, because the Kazoku earned their spots and they maintained them, despite lacking preexisting advantages.

In South Korea, despite being conquered, placed under a dictatorship, fought over extensively, and totally rebuilt from the ground-up, a family’s test score prior to 1898 still predicted educational attainment all the way to 2000. South Korea did not even have the luxury of having physical capital in place, as the North was the part with more capital prior to the Korean War. Social status persistence in South Korea was comparable to other countries in terms of social status persistence despite all it went through in the 20th century.

Other highlights include Catholics and Protestants in Ireland, Gypsies/Travelers, Jews, Copts, and more. A prominent example is Jews, who, if our family lore is to be believed, largely came to America with nothing, but achieved everything. Importantly, social status persistence in the United States went both ways. Groups like the Hmong, who were a poor refugee group from Laos, maintained their low levels of social status. Given the sheer number of groups, from the French - an underclass - to Koreans - an elite - in the United States who have maintained their respective social statuses across borders, theories of status persistence that invoke kin and social networks are hard to believe.

This status persistence is not attributable to ethnicity, it holds up with immigrants, and it has not changed going from the 19th century to the 21st. Importantly, it is more consistent with a genetic model of status transmission than one based on parental investment and community socialization. But we can go further with this. Some groups took extreme losses and their descendants still maintained their social status.

For this example, consider the Mandarins and the Nationalists. Nationalists were relatively elite before they fled to Taiwan. When in Taiwan, they maintained high social status across generations, again, despite losing their physical and social capital. China’s exam-dominating elite, the Mandarins, were the subjects of extreme persecution domestically. They had their properties confiscated, their privileges revoked, and their status reduced to penury. And, as Clark records, they maintained their status despite this. Their lives were ruined, they were sometimes relocated, and they had no capital to pass on to their kids, but their descendants still had higher status than their non-Mandarin descended peers. This was confirmed again in a more recent paper, which allowed for this wonderful graphic:

And we can get even more extreme. Think not just class enemies like the Mandarins and Nationalists, but Enemies of the People, like the intellectuals of the USSR. These persons were moved from where they lived throughout the Gulag system. They had their livelihoods taken from them, and they lost their freedom too. Their children had no physical or social capital to take advantage of. And yet, the descendants of these enemies of the people are more successful today. More importantly, the areas their descendants live in have higher productivity, more profits per employee, and greater average wages today. Perhaps more importantly, the fall of communism coincided with an increase in the raw predictive power of polygenic scores in both Estonia and Hungary. But there was still status persistence, both from on high and on low in Hungary after the fall of the USSR. Reconciling these results requires noting that privileged groups in politics were wiped out by the fall of communism, as when it fell, there was sharp mobility for political elites specifically, and the outcomes being predicted were specific rather than general status.

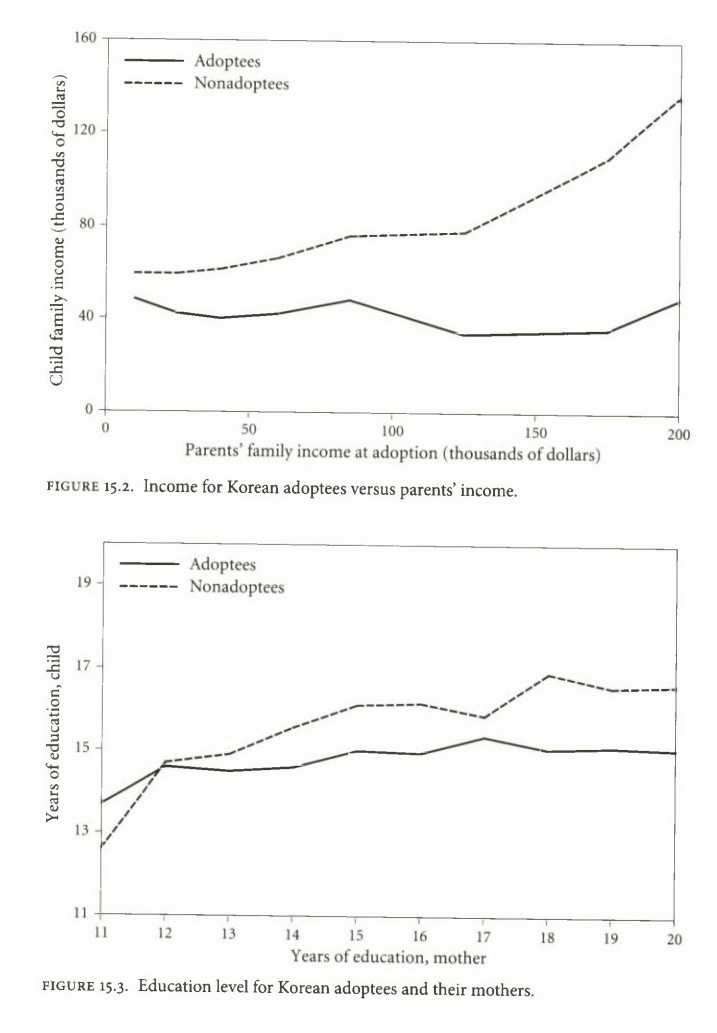

All of this evidence is consistent with a genetic model, and the realities of genetic data. Notably, genes predict outcomes within and between families and classes, the vast majority of the variance in intelligence is genetic in origin, and the same is true for personality when it’s measured well, with substantial implications for the transmission of social status-cultivating trait transmission between generations. As noted by Clark, this likely resolves why adoption studies generally do not show status correlations between adoptees and their adoptive families after selection is taken into account. The following figure is from his book.

But there’s still a more specific question of what behaviors allow people to recover from losses. The mechanisms are certainly multifaceted. For example, only relatively intelligent people adjust their behavior as prescribed by the consumer Euler equation and, intelligence predicts beneficial stock market behaviors, and genes predict rates of return in the stock market. I believe that to understand this more fully though, one has to flip the coin and go from discussing persistence through surprising losses and immigration to also discuss windfall gains.

In the Cherokee Land Lottery, almost every White adult male in Georgia participated and winners earned a large windfall that was unrelated to their underlying status or ability. The windfall was roughly the median level of wealth in general, and thus, it was very large. Winners had a few more kids than nonwinners, but they did not prioritize their children’s educations more than nonwinners, and their sons ended up no better off than nonwinners’ sons in terms of wealth, income, or literacy. Furthermore, their grandchildren did not show any higher literacy or school attendance. In an interesting twist on this, Cherokee casino profits present another experiment in windfalls failing to generate intergenerational gains. The youngest kids in the sample felt the gains through their family’s incomes, and at age 18, if they graduated high school, they would also start earning casino profits. So, with that incentive in place, they did complete high school more often, in addition to doing fewer minor - but not major - crimes. Otherwise, living conditions hardly moved. In a final example, the Norwegian oil boom led to increases in the value of labor, effectively providing some areas with windfalls. Income improvements at the family level did not transfer to improvements in children’s education levels.

In short, it is largely not wealth itself that propagates wealth, but the traits underlying typical wealth acquisition. Where we see exceptions, we are looking at too few generations, or systems in place that perpetuate a given class’s position artificially. Unless such a system fully suppresses potential, we’ll still see a remnant of this transmitted status’s effect. When such systems disappear, status converges to where it would with a more equal expression of underlying status-producing traits.

A likely mechanism explaining why windfalls and surprise deprivation fail to affect status intergenerationally lies in the behavioral response to status changes. There is some evidence that households will adjust their consumption for expected income changes that are large, consistent, and predictable, and increases in income lead to increases in consumption. Likewise, government spending can increase individuals’ consumption and anticipated positive changes in income decrease people’s marginal propensity to consume, but when these changes are small, they tend to increase it.

In Massachusetts and Sweden, lottery winners reduced their earnings after wins, and the larger the lottery win, the larger the reduction in earned income. In Golosov et al.’s estimation, every $100 in wealth provided by a lottery reduced annual earnings by $2.3. Winners did not need to work, so they reduced the amount they worked. But more importantly, winners’ long-term wealth often isn’t improved by windfalls. Using the Florida lottery, Hankins, Hoekstra & Skiba found that winning small lotteries did not affect long-term bankruptcy risks, and winning a larger lottery only momentarily reduced risk, whilst in the longer term, increasing it before it returned to the typical rate. Moreover, the debts, assets, expenditures, and incomes of lottery winners who subsequently declared bankruptcy did not differ based on the size of their winnings. Similarly interestingly, NFL players do not smooth their consumption over their lifespans: they simply spend more. There’s a high rate of bankruptcy filing after players stop playing, and this is largely independent of how much they earned and how long their careers were.

So, stating the mechanism simply, people who experience windfalls choose to spend more and earn less than would be expected in their lineage. People on the other end, who are relatively more deprived than might be expected in their lineage, will tend to aim for higher earnings and more scrimping, sometimes even choosing to concentrate their investments in human rather than physical capital or move to locations less affected by economic downturns.

The children of slaveowners come from relatively high status families, and will tend to preserve some of their parents’ status for reasons that are inherited. Since the descendants of masters were overrepresented among those manumitted by masters, this can be a substantial source of bias. The next source of bias won’t take as many words to appreciate. This one is simple: regardless of your explanation, European admixture will improve the status of slaves manumitted due to their parentage.

One route through which this is true is discrimination, also known as colorism. The descendants of Whites and Blacks should receive less discrimination than the descendants of Blacks alone, because they will appear shifted towards being White, and will, in many cases, be able to pass themselves off as White. The skin color pattern with respect to social status exists across the entirety of the Americas, rather than in the U.S. alone. It also exists among immigrants.

But the other explanation is that admixture shifted qualities like the ability distribution. To explain this requires a few pieces of knowledge. Namely, for latent variable models and identification in behavior genetic models work. In brief, behavior genetic models are latent variable models used for variance decompositions, in which the variances are causally identified by way of knowledge about theoretical quantities like relatedness in different groups. The most common behavior genetic model is the ACE model, in which a phenotype’s variances from additive genetics, the shared environment, and the nonshared environment are computed, typically with groups of twins, since we can identify the additive genetic variance component by exploiting the fact that monozygotic twins are genetically identical and dizygotic twins share an average of half of their genes.

If we believe a latent variable to be “real”, in the sense of causing covariation between a set of items tests, or what have you, it will have a corresponding common pathway model. As an example, such a model fits for intelligence but often not when it comes to personality. Instead, for personality, an independent pathway model fits better, meaning that the covariances among personality indicators are due to specific shared genetic and environmental influences rather than a general one that overarches all of them. When these models are fitted for intelligence-like data, it becomes clear that intelligence is extremely highly heritable. This paper from 2020 by Paige Harden et al. includes a good example.

The heritability of intelligence here is 86.49%, which is higher than the heritability for each of the individual subtests, which contain reliable non-intelligence variance and error variance, for individual heritabilities of .42, .62, .50, and .74. We can also fit these models for mean differences. The method for this is quite old, but more recent papers have broadened it to allow for the decomposition of means in ordered-categorical variables, and some have even applied the method to several outcomes. For example, that last paper applied it to male-female differences in politics, this one applied it to sex differences in alcohol use, this one applied is to racial differences in birth health risk, and most importantly, this one applied is to racial differences in intelligence. It found that genes accounted for 66-74% of group differences. We can expand on this with the NLSYLinks dataset. Fitting hierarchical common pathway models to the AFQT/ASVAB data from the NLSY’s two waves, from ‘79 and ‘97, we can check for support for intelligence as a construct, and then decompose the mean differences. With that said, a common pathway model fits better than an independent pathway model, and the heritability of intelligence ended up being 90% and 92%, while the between-group heritabilities were 77% and 84%.

Another way to get to the conclusion that admixture from slave owners is a source of bias is to simply look at admixture studies. Again, and again, and again, and again, and again, it appears that among individuals, counties, countries, provinces, etc., admixture predicts intelligence, socioeconomic status, and so on and so forth. It does this when controlling for sex, age, skin, hair, and eye color, and socioeconomic status, and it even does so within racial groups. Moreover, this relationship is measurement invariant by European ancestry in samples of both White and Black Americans, and Black Americans alone. What this means is that, all across the range of European ancestry, the causes have to be shared; they cannot be qualitatively different or act differently. If we want to suggest, for example, that socioeconomic status influences IQ, but we know IQ measurement is invariant by group and we see that socioeconomic status is only related to IQ in one of the groups but not the other (and we have power for that determination), then socioeconomic status is not a cause of either IQ or group differences in it. As it happens, this is the case for some aspects of socioeconomic status, and as Jensen explained in his The g Factor, (graph from it pictured below), this is likely due to differential regression to the mean.

Even if we want to be maximalist about socioeconomic status confounding of ability differences between races, ignoring genetic confounding, adoption studies, windfalls, and so on, it hardly seems to matter, since the delta when there aren’t socioeconomic differences is still the vast majority of the gap. For example, in this study, the Black-White gaps in mathematics and English language arts achievement were mostly preserved when there were not differences in socioeconomic status, at the district and metropolitan area level. In that study, socioeconomic status was defined by the log of median family income, the proportion of adults with a bachelor’s degree, the poverty rate, the unemployment rate, the SNAP receipt rate, and the single-mother-headed household rate. Speaking to the quality of this composite, it is probably very good and comprehensive, since income is approximately wealth for most of the population, and education is more important for predicting intelligence than income, the latter of which is a finding replicated in the district/metropolitan gap and SES study. The mean Black-White gap across metros is .73, and across districts, it is .66. When this composite doesn’t differ, the gaps are .45 and .52, or 62% and 79% as large. When assessing the size of the gaps across levels of school poverty exposure, when those are equal, the gaps are .55 and .58, or 79% and 83% as large.

Altogether, the selectivity of escape, purchase by a third buyer, self-purchase, and manumission by master should be considered high, and the risk of selectivity biasing them, considerable. Emancipation in the north is the only remaining source of bias proffered by the authors, and it is incorrectly labeled unselective. For the same reasons that admixture is biasing - effecting discrimination risk and affecting ability - so is the emancipation of northerners because they were far more likely than southern Blacks to be mixed-race. The census recorded figures for this.

As can be seen, in 1850, 28.96% of the northern Black population were at least half-White, versus 10.14% for the southern Black population. Blacks were 286% more likely to be half-White in the north. In 1860, this number changed to 252%. The following quote from right below this table is important to understand:

Comparing the northern division with the southern, a greater proportion of mulattoes is found in the free States. But this peculiar feature can be referred to either of two suppositions, namely: that the mulattoes have multiplied excessively in the condition of freedom in the northern States; or, on the other hand, that in the manumission from slavery, the mulattoes have had greatly the preference over the pure blooded Africans. [Note: This latter conclusion is unavoidable if one believes in any of colorism, kin preference, or racial preference generally.] To determine which of these suppositions is the correct one, let equal numbers be taken in the proportions existing in 1850 and in 1860, as shown by the columns of Proportions. On a common scale of 100 colored persons, irrespective of civil condition, the mulattoes will be seen to have gained 1.99 per cent in ten years in the free States, and 2.16 per cent in the slaveholding States in ten years, thus showing but little disparity at the present time in the prevalence of such admixture. This conclusion excludes the first supposition above and confirms the second, that the greater number of mulattoes in the condition of freedom has arisen chiefly from the preference they have enjoyed in liberation from slavery.

And further down, the paper provides yet more numbers that are highly relevant. For example, it provides numbers of free Blacks, with numbers for half-White persons. In 1850, there were 196,308 free Blacks in the non-slaveholding states, compared to 238,187 free Blacks in the slaveholding states. In the non-slaveholding states, 56,856 were half-White, and in the slaveholding states, 102,239 were. In other words, 29% of free northern Blacks were half-White, and 43% of free southern Blacks were. This compares to 7.7% of the slave population which was half-White. In 1860, there were 226,052 free Blacks in non-slaveholding states, and 261,918 in the slaveholding states, and 69,969 and 106,770 of them were half-White. In other words, the free population in the non-slaveholding states was 31% half-White, and in the slaveholding states, it was 41%. The slave population at the time was 10.4% half-White. The disproportionality is obvious, and in some places and time periods, it was even more disproportionate.

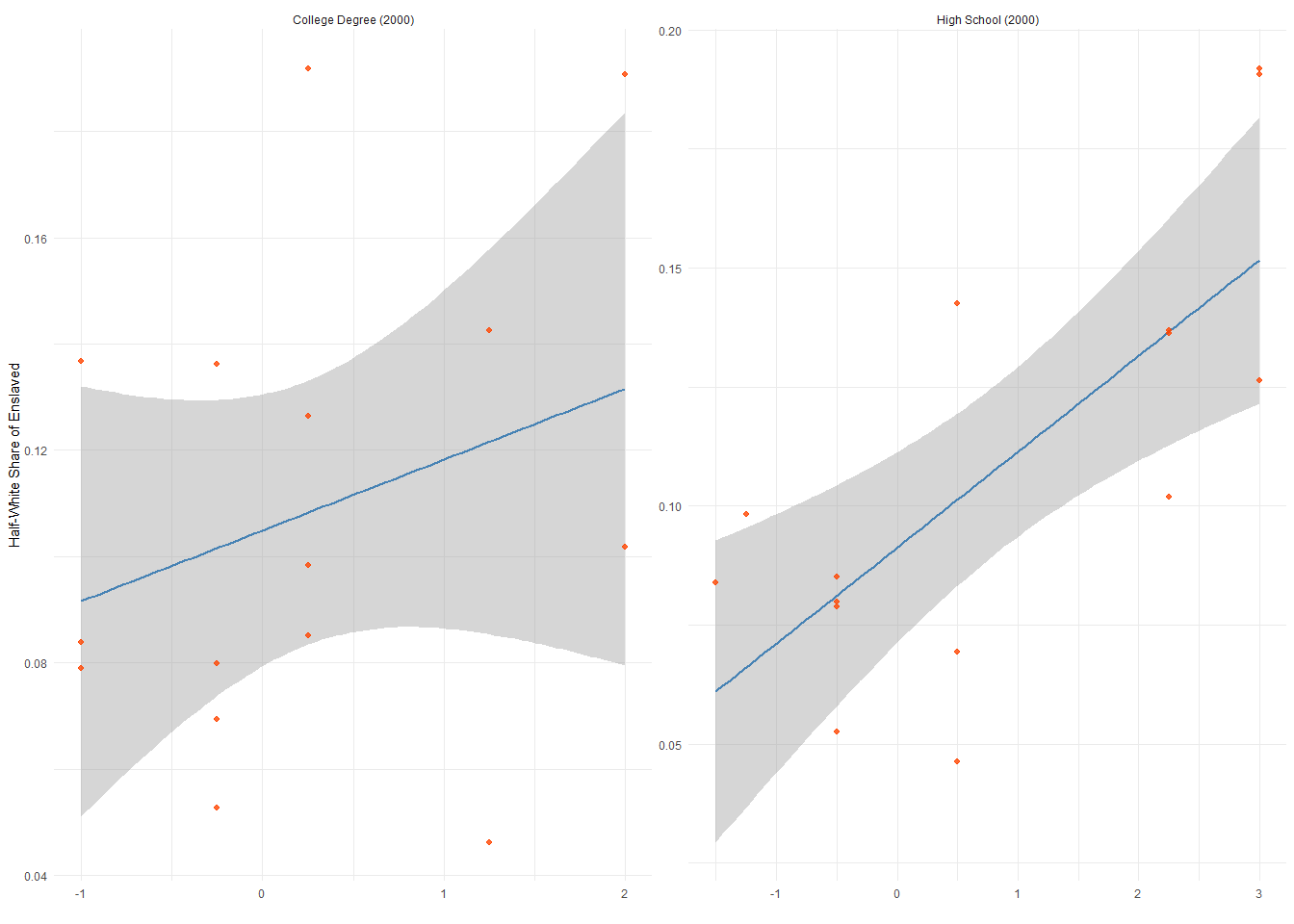

To push this point home, using Althoff & Reichardt’s data on state-level effects on high school degree attainment and college degree attainment in the year 2000, we can combine it with the census data on proportions of the enslaved who are half-White by state, and then assess how related they are. An admixture effect as specified here should generate larger state effects the more a state’s slave population had European admixture.

The more European admixture a state’s slave population had in 1860, the higher their descendant’s educational attainment.

All in all, the estimates of geography effects are biased, and the magnitudes are accordingly overestimated, but also almost certainly not eliminated. They may be eliminated by today though - the provided estimates of slavery effects in the year 2000 cannot speak to that and the post-1940 mobility increase in the South supports the possibility. Combining the benchmark results, the within-county results, and the high levels of suggested confounding to the study’s geographic effect estimates suggests that whatever effect slavery had is now virtually indistinguishable from nothing. The Clarkian take on status has come out substantially correct: beyond the trivial, whatever travails American Blacks suffered during slavery no longer matter for their socioeconomic attainment today.

Thanks. I've been thinking about a mechanism behind what you observe.

Looking at the map graphic on p. 9 of the article, it appears that there were far fewer free blacks in the cotton-growing slave states that had opened up in the 19th Century than in the older states, slave or free.

My guess would be that free blacks tended to accumulate in a place generation by generation, due to masters freeing their children, manumissions by humanitarians, and self buy-outs.

But the Cotton Belt was populated by a large scale migration as the Indians were pushed out in the 19th century. This migration from the eastern seaboard west appears to have served as a selection event, with free blacks being left behind. The authors argue that there wasn't selection of slaves who were forced to migrate by their masters' moving west to plant cotton, but there was clearly selection on the black population as a whole, with very few free blacks moving into the Cotton Belt.

Further, there was probably selection among urban slaves being left behind, with relatively fewer city-dwelling masters than plantation-masters, which likely made the Cotton Belt slave population more rural and less urbane than the Eastern Seaboard slave population.

This probably had some effect on the post Civil War trajectory of Jim Crow, with whites in states like Mississippi with black majorities and virtually no bourgeois black pre-Civil War freedmen to act as intermediaries, being especially extremist about rigging the laws to keep blacks down.

Thanks. Great stuff.

Just a minor note for anybody wondering why many of the graphs lack a data point for 1890. It is because the detailed Census archives for 1890 burned up in a fire.