Climate Change is a Policy Choice

A brief reminder of what the Messmer Plan shows us

The need to curb climate change is a pressing one. If it continues without abatement, the world will become a more miserable place. The ways it’ll do that are well documented elsewhere by numerous others, so I won’t delve into them. But I will note the results of a new study that asks and answers the following question:

What can we do to get people to reduce their carbon footprints?

Global Interventions

Vlasceanu et al. recently published their evaluation of a massive 63-country global intervention tournament in which eleven expert-sourced interventions based on behavioral scientific findings were pitted head-to-head to see which would work best for improving climate change beliefs, bolstering environmental policy support, increasing information sharing intentions, and getting people to take action to save the climate.

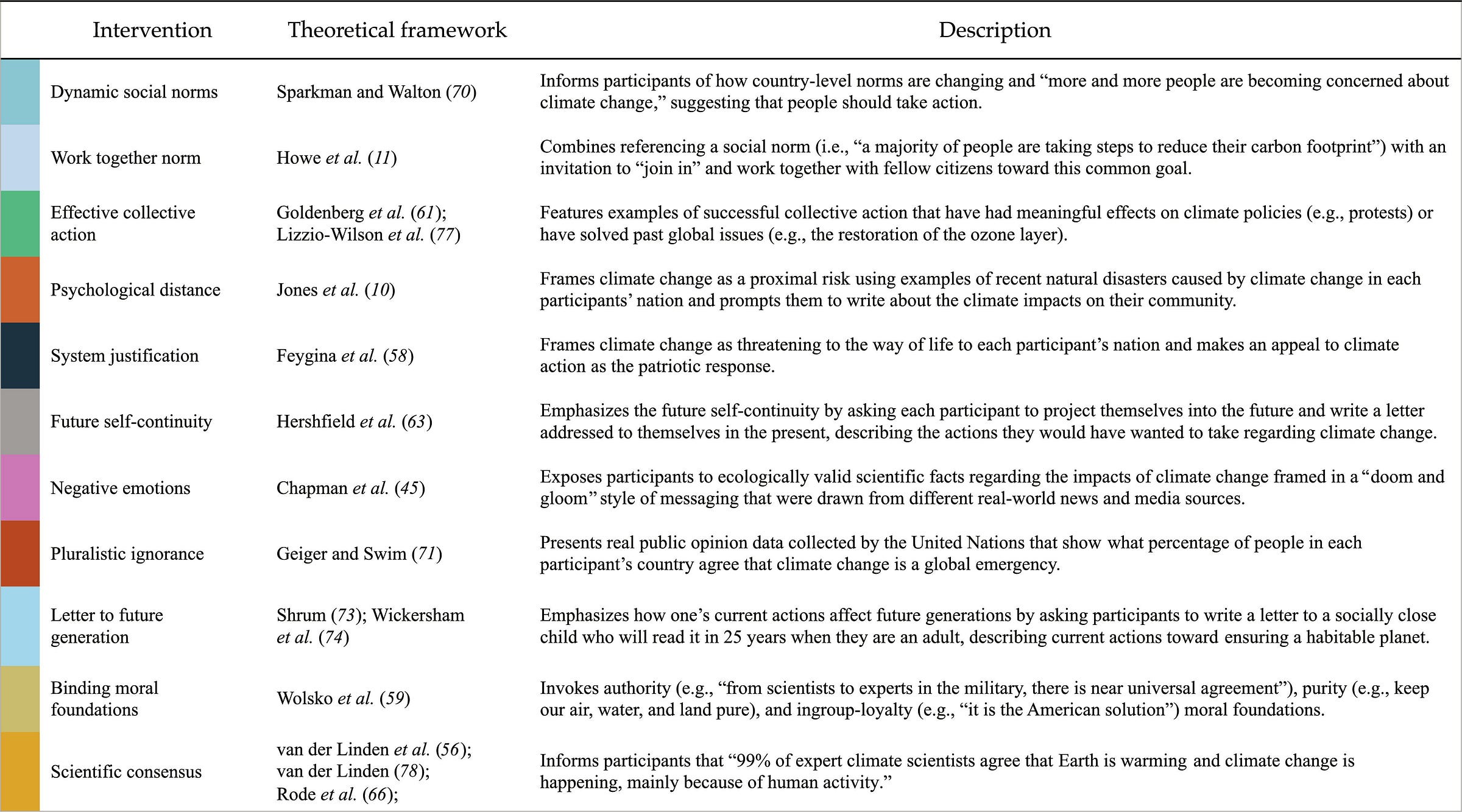

Participants in the study were randomly assigned to one of the eleven different interventions or to a control condition in which they read a short literary text. The interventions were as follows:

These interventions, at a glance, are certainly paternalistically inspired, but they also seem to be condescending and polarizing. I don’t know if the researchers behind them felt that way. Because their goal was for them to work, I doubt they did, but man do they. If I encountered most of these, I would just be irritated, but perhaps I’m odd.

Or maybe I’m not alone and it’s the researchers who are strange. From Ireland to India to Peru, it seems the impacts of the interventions were minimal and sometimes even harmful.

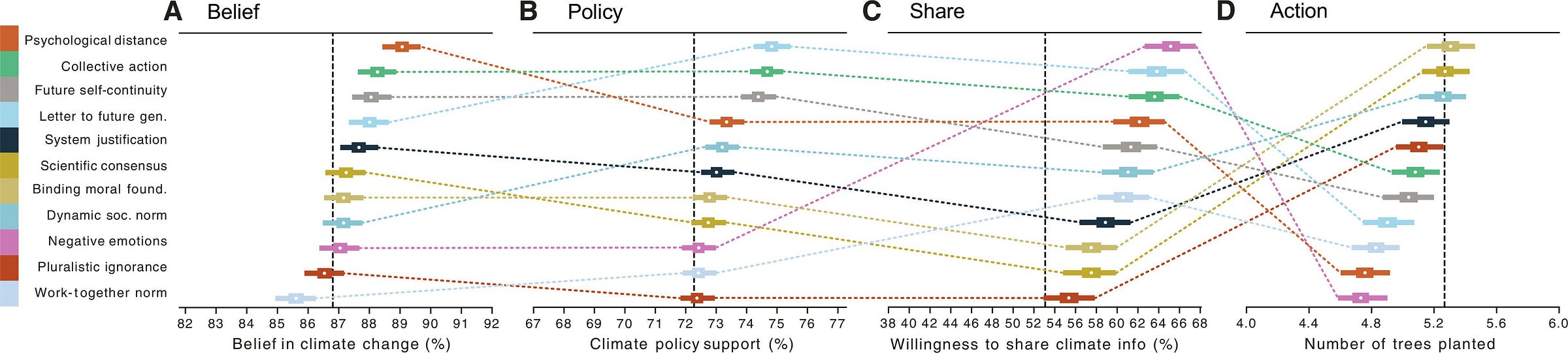

First, most interventions failed to elicit much change in beliefs in climate change. The most effective intervention increased beliefs by 2.3% compared to the control.

Second, most interventions failed to elicit much change in policy preferences, with the most effective intervention increasing climate policy support by 2.6%.

Third, interventions seemed to get people engaged and led to fairly consistently to increased willingness to share climate related information, with the largest effect being an increase of 12.1%.

Finally, the meatiest outcome was performance in a tree-planting task where participants were asked to voluntarily exert cognitive effort, screening for specific numerical content with the reward for doing so successfully being actual trees planted by the Eden Reforestation Project. Interventions were associated with, at best, getting as many trees planted as the control group, and more typically, getting fewer planted.

Overall, the results are fairly minimal.

The first two outcomes don’t mean much. Climate change belief is already high in this sample, and belief in climate change usually isn’t well-informed and rarely ever leads to meaningful policy support. People just don’t want to be immiserated, so when it comes time to call for typical climate policy-matter, support means nothing. People don’t want to put up with government-imposed austerity even more than they’re opposed to personally imposed austerity.

In this trial, the beneficial effects of the interventions were problematically heterogeneous, so whatever gains they might bring are probably small:

The results… indicate that the impact of the interventions on each outcome depends on peoples’ preexisting belief in climate change…. For belief, the effectiveness of several interventions (e.g., decreasing the psychological distance and collective action efficacy) was maximized among the uncertain, with lesser effects among believers and skeptics. For policy support, however, interventions were generally only effective among those with high initial levels of belief, with negative emotions backfiring among skeptics. Similarly, the robust increases in willingness to share on social media were largely restricted to people who already believed in climate change—with negative emotions increasing sharing intentions even among skeptics. For the higher effort behavior, however, interventions appeared to uniformly reduce tree planting across all levels of initial belief.

Sharing might be polarizing, and the message it sends reinforces practical resistance to policy. Consider some example mitigation information the study asked about sharing on social media:

Did you know that removing meat and dairy for only two out of three meals per day could decrease food-related carbon emissions by 60%?

Ultimately, this is asking people to give up a joy in life for an abstract benefit to the climate that they can readily justify not caring about. It only takes a moment of looking to find plenty of people who object to this sort of call for personal austerity by invoking how politicians zip around in private jets enjoying themselves while calling for their lives to become worse.

The point about how the interventions reduced people’s actions is probably a mistake having to do with wasting participants’ time:

[In] an exploratory analysis, we assessed the effects of the interventions when adjusting for the time spent on each intervention. While we still observed the negative effects of some interventions on tree planting, we now also observed positive effects of five interventions. That is, when controlling for intervention length, binding moral foundations, scientific consensus, dynamic norms, pluralistic ignorance, and system justification all increased the number of trees planted compared to the control condition. Thus, in the absence of time constraints, these interventions might increase proenvironmental behavior. However, the degree to which these findings actually generalize to proenvironmental behaviors that do not hinge on time (e.g., donations) should be assessed in future studies.

Overall, what this study ends up saying is what it doesn’t come out and say: we’re not going to address climate change by asking people to change their behaviors.

Cool in a Crisis

In France, we don’t have oil, but we have ideas.

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries—OAPEC—embargoed the countries who supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Overnight, the resulting oil crisis struck the nations of Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with Portugal, Rhodesia, and South Africa soon to follow.

Across the developed world, gas rationing became commonplace. Oregon banned Christmas lights; gas stations closed down from Saturday night through to the following Monday; Labour told Britons to heat only one room in their homes in the winter; Japan cut back on their air pollution regulations so businesses could stay afloat after the government foisted a 10% energy usage cutback on industry, and the Soviets tried to use the crisis as an opportunity to convince Japan to give up its claim to the Kuril Islands in exchange for oil (Japan refused). The crisis had major global implications and resulted in a fair amount of oddball policy. For example, in David Frum’s How We Got Here: The ‘70s, he recorded that, in the Netherlands, prison sentences were handed out for exceeding the electricity ration.

But the most lasting impact on any nation was likely what happened in France.

In response to the global inflation that ensued, France put its foot down, and then-Prime Minister Pierre Messmer set in motion the French transition to being nuclear-powered, so France could reduce the odds of having its economy strangled by hostile nations again.

Marcel Boiteux managed the effort carefully and his reactor fleet ended up costing France fractions of what Germany’s ongoing Energiewende has. The work paid off and by 1990, France was the world’s most dominatingly nuclear-powered nation.

Today, France engages in spent fuel reprocessing and manages the cleanest large-scale power generation of any major nation. France is the nuclear power.

And that’s that. All it took for France to nuclearize was an incentive to push policy in the right direction, after which it became a largely nuclear power in less than a decade and a half. Even more impressively, because France manages the entire nuclear loop, their system likely produces even fewer emissions than nuclear is estimated to generally.

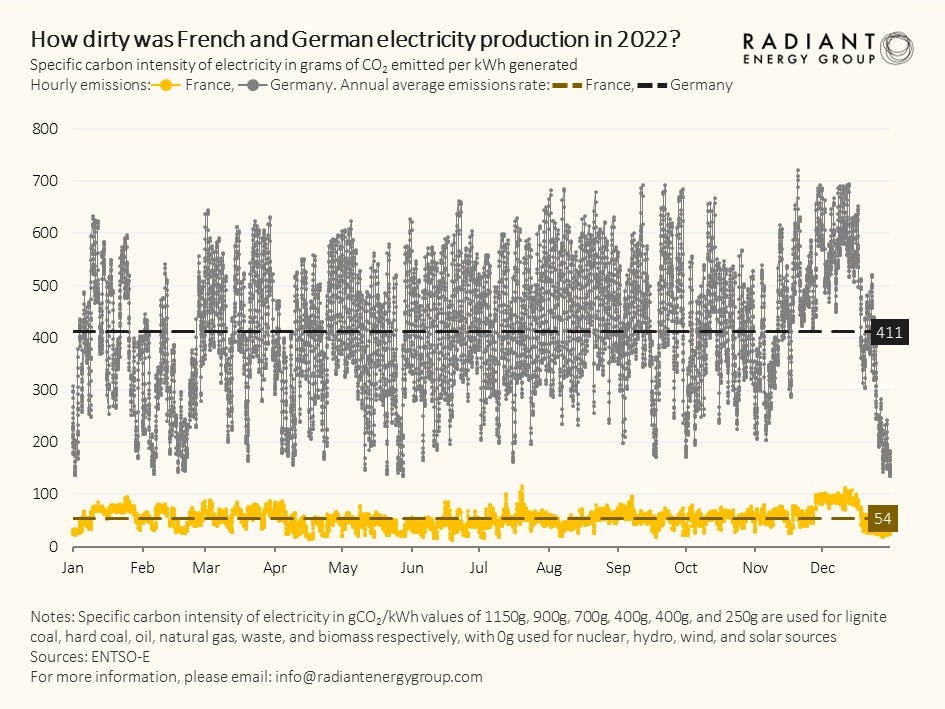

Compare French and German emissions. Here’s an insightful way of doing that with data from 2022:

The oldest version of this chart is for 2015, and Germany has certainly improved since then, but it’s still no match for France: