From Caveman to Chinaman

How man went from bumbling around in savannahs to building the Great Wall, and why China fell behind Europe

Where there are three men walking together, one or other of them will certainly be able to teach me something — Confucius

Anatomically modern humans first appeared roughly 200,000 years ago1 and after several false starts, the global dawn of man took place with a series of dispersions out of Africa around 60,000 years ago. By 40 to 50 thousand years ago, humans were dispersed across Eurasia and Australia, and by 10 to 20 thousand years ago, they had spread throughout the Americas too.

For almost the entire time humans spent dispersing throughout the world’s major landmasses, they roamed as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Before the advent of sedentism and the closely-related phenomenon of agriculture, hunter-gatherers lived everywhere man can be found today, from its more resource-poor, desolate locales to the places we might have once considered Edenic. Where man could go, man went, and he subsisted much like man anywhere else.

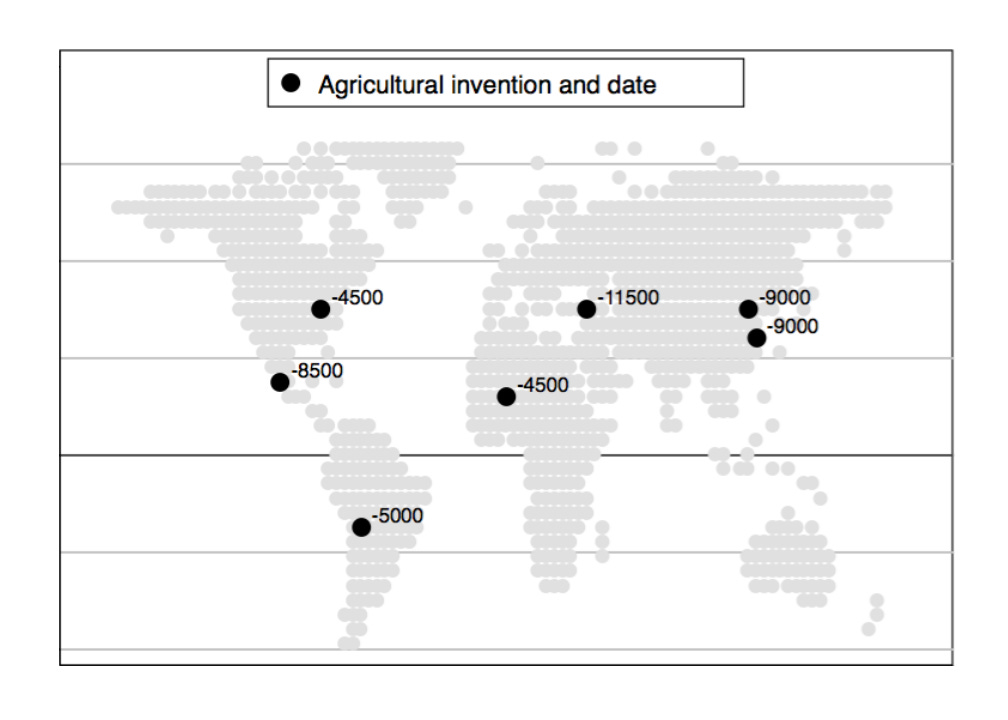

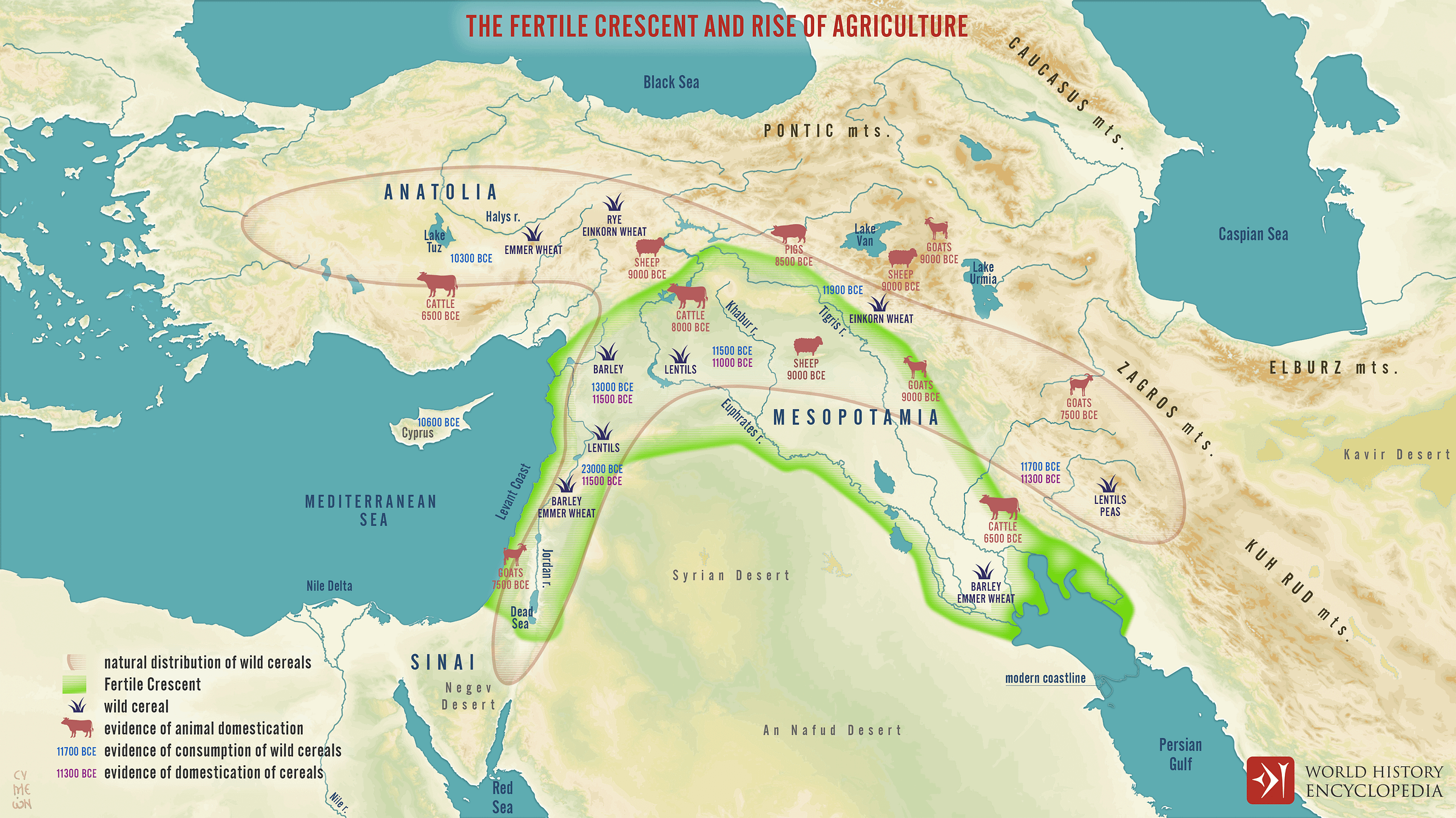

Then, suddenly, in a five to seven thousand year burst, no fewer than seven locations independently developed agriculture. These locations did not adopt agriculture from one another, were not engaged in long-distance trade with each other, and weren’t even related by conquest; there was no cultural exchange that explains how all of these places took to the plough and the field simultaneously, and yet they did.

A theory sufficient to explain this requires six elements:

Something that was absent when humans were exclusively hunter-gatherers;

Something that became common roughly 10,000 years ago;

Something that was present in the places agriculture emerged;

Something that comports with the observation that the agricultural revolution negatively impacted human health;

Something that lets people settle down even if they don’t know how to farm, and;

Something that can explain all of that despite differences in crop availability, farming techniques, and cultures.

In his The Ant and the Grasshopper (alternatively: The Gift of Persephone), economic historian Andrea Matranga argued that there is a candidate. For various reasons, it’s not megafauna extinction; gracefully transitioning from limited horticulture to farming; animal husbandry being similar enough to farming to enable a rapid transition to farming; or simply global warming. Matranga’s explanation is quite literally astronomical.

In Matranga’s telling, humans made the change from hunting and gathering to farming because of changes in Earth’s seasonality.

Briefly, seasonality is primarily dependent on three factors. The first is the Earth’s tilt, or obliquity, which determines how hemispheres will be tilted towards the Sun in summer and away in winter. The other two factors are lesser-known, but they are nevertheless important. They are the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit, which is how elliptical it is, and the precession, which is about whether the Earth’s closest approach to the Sun happens in the northern or southern hemisphere’s summer season.

Each of these parameters changes over time as part of Milankovitch cycles, which are largely driven by the orbital pull of Jupiter. Thanks to our gas giant neighbor, there was a coincidental syncing up of each of these parameters’ motions that made the Neolithic a period of extremely strong seasonality relative to practically any other time anatomically modern humans have been around.

For astronomical reasons, we now have extreme seasonality in the northern hemisphere. What next? Milutin Milankovitch predicted that this should end ice ages since warm summers melt ice and cold winters don’t have the opportunity to lay down as much snow. This change meant winters stayed miserable, but summers became more agriculturally favorable. Nearer to the tropics, there were even some exceptions that proved the rule about the importance of seasonality, as hunter-gatherers in those regions experienced stronger monsoons, a form of precipitation-based seasonality.

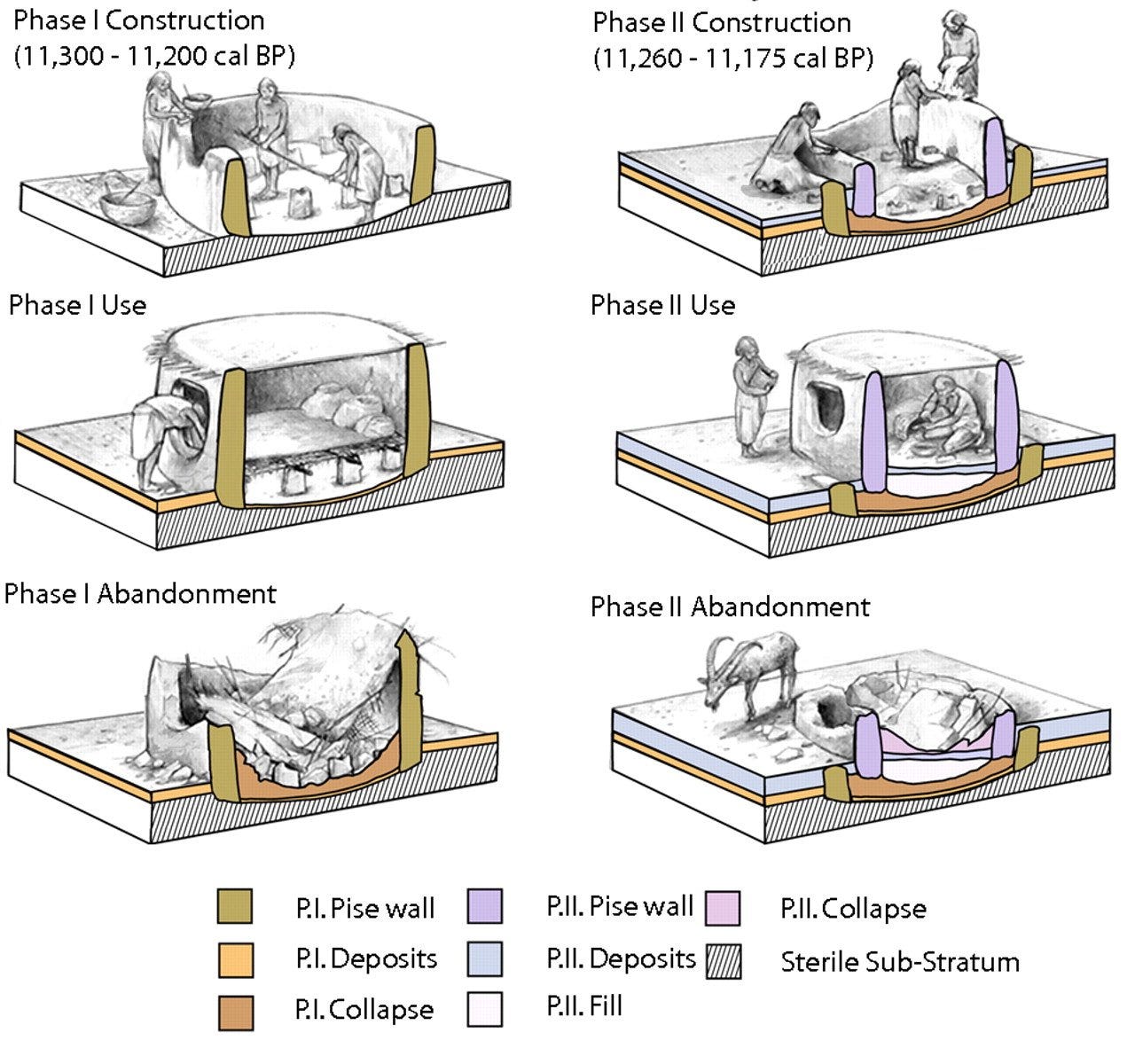

Seasonality is important for this story because it explains a very relevant phenomenon: farmers without farming. Globally, numerous hunting and gathering groups have been found who became sedentary to facilitate food storage. After becoming sedentary, these hunter-gatherers started acting like farmers do. Their social structures became more complex and hierarchical, they began to practice gifting and showing wealth accumulation, and—critically—they began to partake in consumption smoothing behaviors: saving in times of plenty for the times when food and supplies are scarce. In other words, they started acting in all the ways farming civilizations have been known to, but they weren’t really farmers.

This situation can become possible either due to major advances in storage technology, or due to situations where there are storable foodstuffs that are abundant during certain times of the year and scarce during others, either as they’re harvested or after preparation. Key to the latter strategy is that whatever you’re able to acquire seasonally and store for the thin parts of the year is also something you can move about and cultivate. Lacking those characteristics, people wouldn’t be geographically mobile enough for this explanation to work.

Seasonality in a location with crops that can be cultivated and stored makes it so hunter-gatherers have an incentive to invest effort into the areas they live in, and to stay with those places and their improvements for longer parts of the year. If they garden here or there, build a fence, dig a ditch, and tend to a few crops, those crops soon become many, and if they’re locking the fruits of their labor away, suddenly, the transition to agriculture has begun.

But is there evidence that seasonality actually led to storage behaviors prior to the advent of agriculture? The answer is yes!

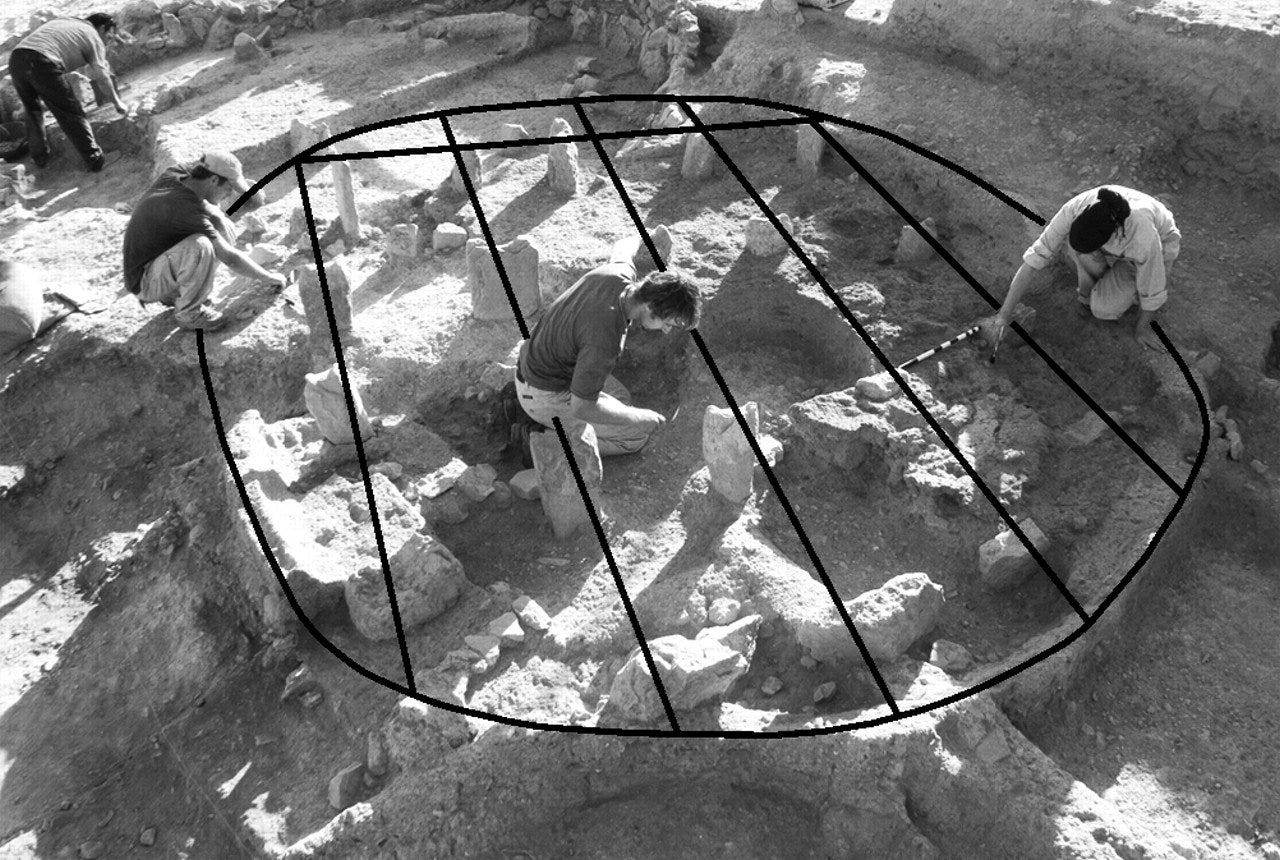

One example comes from when researchers dug up the pre-pottery Neolithic site of Dhra’, among other Levantine digs; what they discovered was nothing short of dispositive. At the dig sites, archaeologists uncovered evidence of floor beams used to hold up suspended floors used to make the bottoms of pre-farming granaries:

The timing of the construction of these pre-farming granaries occurred when Matranga’s theory posits they should start showing up. The whole story fits together, and the usage of these granaries precedes settled agriculture in the region by thousands of years.

This example isn’t alone. Every region where agriculture developed satisfies at least two—and usually three—of the theory’s four core predictions: seasonality, sedentism before agriculture, sedentism before or during storage, and/or storage before agriculture.

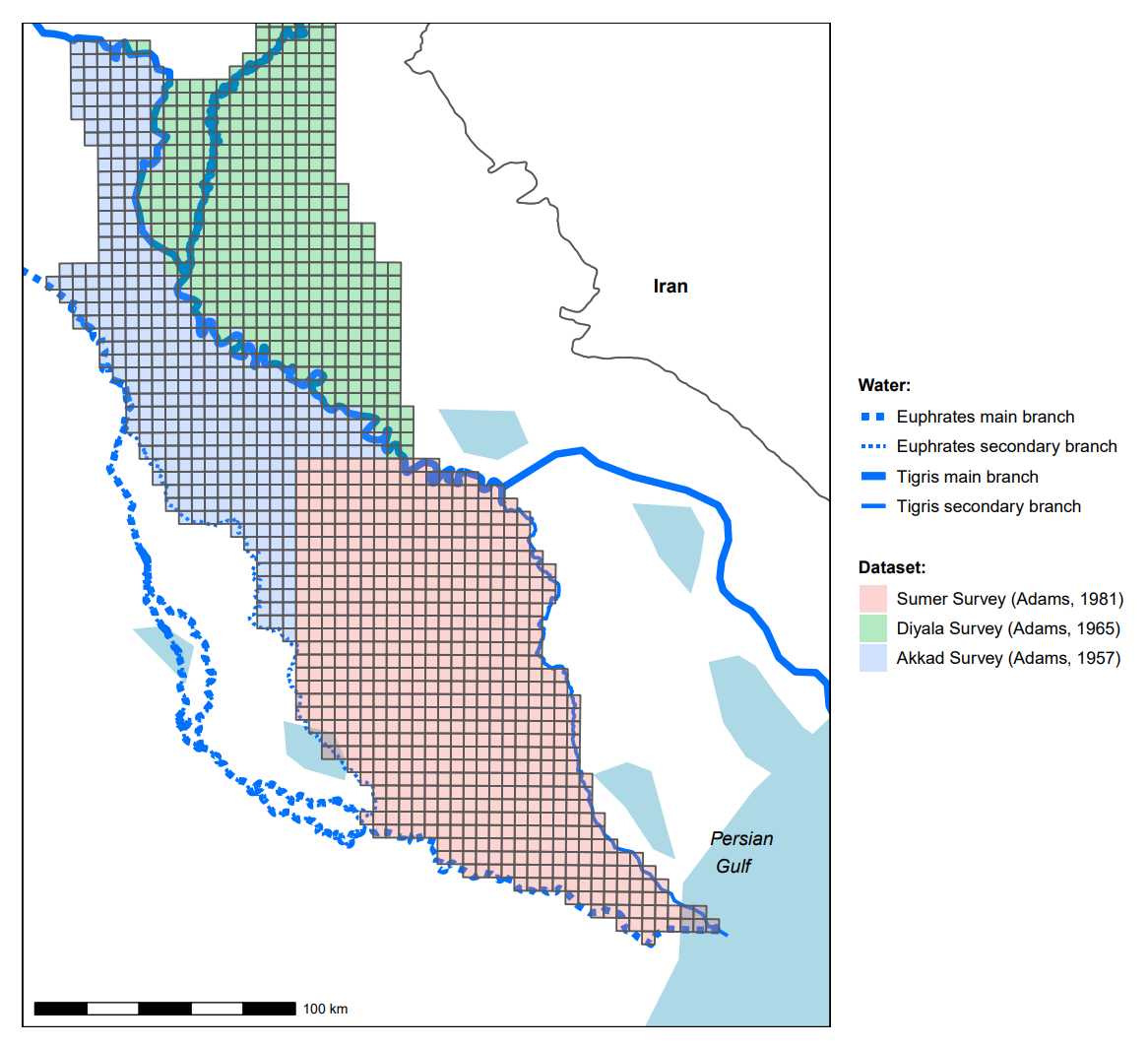

While, so far, the case looks persuasive, qualitative evidence isn’t sufficient for a theory of history to stand on. To make testing systematic, Matranga divided the world into cells with known characteristics like precipitation and temperature in different parts of the year. Those looked like this:

In the regressions used to predict the advent of farming, an additional degree of temperature seasonality was associated with farming arriving roughly 130 to 220 years earlier.2 Also consistent with the theory, seasonality predicted the spread of farming, and all of this predicting worked fine across areas that farmed small-seeded millet or squashes, potatoes, and legumes, or grasses that otherwise had small seeds.

Moving away from regressions, the last thing the theory needs to explain is human health. The transition to farming worsened human stature, it made human jaws relatively narrow and cavity-pocked, shrank people’s legs and arms, and made them appear to be generally weaker. There were decreases “in adult stature following the introduction or intensification of agriculture” in Portugal, Scandinavia, Southern Europe, the Levant, Bahrain, China, Japan, Peru, the Georgia Bight, and the California Channel Islands, no changes in Ecuador, West Central Illinois, and Florida, increases followed by decreases in Egypt and Britain, and “only Thailand and the [American] Southeast saw an increase in adult stature.”

In other words, farming definitely was bad for health, and as Jared Diamond put it, it’s, thus, a candidate for “the worst mistake in the history of the human race.”

The reason the poor health of farmers was preferable to the relatively large stature and physical robustness brought about by the hunter-gatherer lifestyle wasn’t just that farming scaled better or that it made hierarchical organization easier, but also that farming prevented pain.

[Human growth] overwhelmingly reflects the average nutritional status an individual experienced through childhood, while volatility in food intake is only marginally recorded. Acute starvation episodes in children can in fact pause skeletal growth entirely, but if sufficient nutrition is provided thereafter, the child will experience faster than normal growth. This catch-up growth will generally result in the child rejoining its original growth curve and achieving virtually the same adult height as if the starvation episode had not occurred….

[Catch-up] growth leaves telltale signs along the length of the bones themselves. Long bones (such as those of the leg) grow from their end outwards. If a growth-arrest episode is ended by a rapid return to favorable conditions, the body will deposit a layer of spongy bone in the normally hollow interior. These layers, called Harris lines, will form a permanent record of the number of growth disruptions suffered by an individual before the end of adolescence.

The Inuit were traditionally hunter-gatherers of a sort, and each spring, their food intake would skyrocket with the arrival of migratory species, whereas in other times of the year, food was more scarce, and quite often not available at all for fairly long stretches of time. Here are some Harris lines observed in an Inuit adult from the 19ᵗʰ century:

The pain these lines reveal is multi-faceted. There’s the obvious: the personal pains of an empty stomach and the pain that comes from restarting growth and getting yet another growth spurt when catch-up happens. Then there’s the social: the pain of tribes splitting up, conflicts emerging from the harshness of starvation, and the raw emotional pain involved in dealing with the deaths starvation so often leads to.

These lines are commonplace for hunter-gatherers, and rare for farmers. Matranga cites as an example that the nomadic hunter-gatherers of the Central Ohio Valley averaged eleven Harris lines a piece, but when they started to farm, they ended up shorter and with only four lines on average—a marked, and tolerable change towards more reliable availability of food, albeit of a lower quality.

When On High

Agriculture began when and where it did because of coincidences of cosmic proportions that drove man to new opportunities tending his land rather than merely roaming it. Once the hoe had found its way into man’s hands and the plough had found its way into his fields, he spread both inventions far afield, because now his population could grow so long as there was dirt to till and seeds to be sown.

But it’s awfully hard to sow seeds when you can’t secure the homestead and the rain has washed them away. That’s where states come in.

The Babylonian creation myth—Enūma Eliš or “when on high”—begins with a primordial soup, a mixture of fresh water—the god Apsu—and saltwater—the goddess Tiamat. All life came from the marriage of these differentiated water gods.

Apsu and Tiamat first created younger gods, but the younger gods were annoying people who stayed up late, acted rambunctiously, and kept Apsu from sleeping well. Out of annoyance, Apsu decided to slay the younger gods. Their mother, Tiamat, learned of the plan and warned her son Ea, who proceeded to strike first, entrancing Apsu into a sleep and then killing him. Ea then harnessed Apsu’s body to create a home he lived in with his consort, Damkina, and their new son, Marduk.

Apparently Tiamat didn’t expect Apsu to be killed, however, as she went mad when she learned about it. In her madness, she recruited the god Kingu and lent him the Tablets of Destiny, a powerful artefact that contained the secrets of creation and were able to be worn as armor by Kingu. Tiamat also gave birth to eleven monsters and turned into a sea dragon in order to wage her war on the younger gods.

After her intent was declared, the younger gods sought to find a way to defeat her. Everyone agreed: Marduk should kill Tiamat. Ea went to his son and asked him to defend him and his companions, and to become the king of the gods, and he agreed. Marduk defeated Kingu and then went to Tiamat and engaged her in combat for days and days. Marduk eventually caught her in a net he could kill her in with an arrow that split her in two, and from her eyes, she gave birth to the Tigris and Euphrates.

Marduk took the Tablets of Destiny from Kingu and his reign over the other gods was legitimized in turn. After a swift trial, Marduk put Kingu to death and he used his blood to give birth to humans, while the body of Tiamat was used to create the sky and winds, earth and moon, and the mountains. To commemorate his victory, Marduk’s final act is to recite the Enūma Eliš so that it might be remembered.

Outside of the poem, there are numerous prayers to Marduk, and he was worshipped widely. His role, it seems, was to be a canal digger. To quote:

Many sources present Marduk as the maintainer/controller of water and watercourses, and so by extension, the provider of fertility…. Marduk is depicted as the supplier of water by means of (1) water running over the land: rivers, irrigation systems, and the seasonal-flood, and (2) water dropping from sky: dew and rain. As the supplier of water, Marduk is also praised as the god of fertility.

For the Babylonians, the Tigris and the Euphrates had obvious importance, as they were key suppliers of fresh water, and a major source of the region’s well-known agricultural productivity. But they were also prone to flooding, and flooding kills, both directly and through causing harvest failures, lack of shelter, and social collapse. Drought also kills, and the region was so drought-prone due to river movements and changes in the positions of its brinier marshes that virtually everyone was eventually familiar with canals and other means of redirecting water flows and irrigating places distant from water sources.

Babylonian myth has parallels with other flood myths from the region, like the Sumerian Eridu Genesis or the Gilgamesh flood myth, but for my purposes, I want to focus on the Babylonian one because it is the one that’s the most directly connected to the actual history of the region’s states. The chief god being a canal digger makes sense.

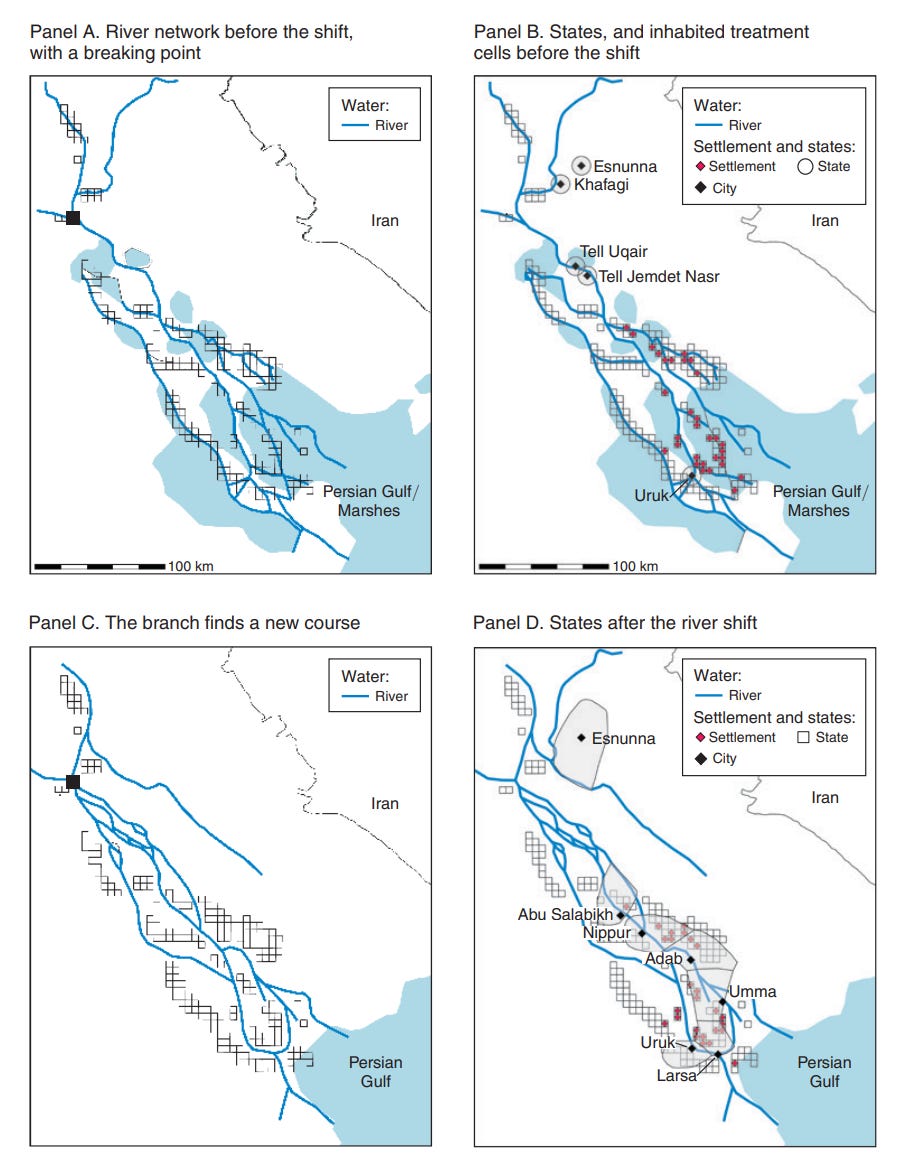

The setting would today be called southern Iraq and the period the story begins is 5,000 B.C. The region at the time doesn’t yet have the Tigris and the Euphrates. Instead, it has the Ur river and its various forks. The region looked unfamiliar to modern eyes, with a notably fluctuating coastline:

As time passed, sediment flowing down the river built it up and elevated it, setting it on a course to shift in the event of high levels of upstream rainfall. In most cases when the natural levees on the sides of rivers broke, the river would barely shift because the break would decrease the flow speed of the river and sediment deposits would fill up the resulting gap in the levee. The shifts that bifurcated the Ur river and gave the region a more modern appearance must have been preceded by large changes in the variability of rainfall upstream. You can see these large changes in this plot of 50-year standard deviations of rainfall in the area of modern-day Turkey relative to notable (numbered) river course changes in the area of modern-day southern Iraq:3

These big rains gave rise to this shoreline and water course appearance by 1,000 B.C.:

These shifts, argued Allen, Bertazzini and Heldring (ABH), stressed local populations in ways that led local elites to start providing state services in the forms of canal building, setting up irrigation, collecting tribute, and so on. The data they used to justify these conclusions was derived from sets of archaeological surveys that took place in the region, with results split into 5x5 kilometer grid cells, like so:

To build a graphical intuition for how this works, consider the following sets of figures that show the impact of a river shift on governance, settlement, and city development. In panels A and B, you can see rivers and states, respectively, prior to the river shift, with the first point where the river breaks indicated in black in panel A. In panels C and D, you can see rivers and states, respectively, after the shift river, with the place the surge in river water over the levees took place marked in black in panel C. Statehood can be seen to coincide with grid cells impacted by the river shift, and the formation of states is clearly concentrated where habitation took place prior to river shifts. In other words, states formed where people had a newfound need for elites to bring them irrigation so they wouldn’t have to move to the new river location.

Using a difference-in-differences design, a cell being impacted by a river shift is related to subsequently being under a city state (p = 0.0005), being under a new state (p = 0.006), but not being under an existing state (p = 0.32). When the river goes, demand rises, and the state comes in, with its biggest impacts where there are actually lots of people in need of a state:

One possible explanation for these results is less canal digging beneficent rulers who benefitted the public, and more warlords who kicked people while they were down, imposing rule when people were weakened by the hazards and harms of riverine shifts. But we know this is not so, because there was record-taking, and we are certain that states brought canal building and the construction of protective walls (p’s = 6.3e-5 and 0.006), while, yes, calling for tribute and setting up administrative buildings (p’s = 0.0005 and 0.003). Cuneiform tablets also confirm this, as they start talking about leadership positions far more often after rivers shift, and they also go from barely mentioning canals to their mention being commonplace, while tribute shifts from being unmentioned to also being quite common.

Eventually, the process of formally organizing in response to geographical changes turned states from a rare occurrence to a universal across the entire landscape of the fertile crescent. Once states were there for long enough, their existence was a settled matter, and all it took to get that process started was for farmers to cry out for organization.

Aristotle, Marx, Wittfogel

The water-based states that emerged from the need to supply irrigation (and defense) at scale are now sometimes referred to as “hydraulic empires.” These states have been argued to be particularly despotic, but it’s not always clear what that means. When Marx wrote about the “Asiatic mode of production,” these are what he was referring to.

For Marx and Engels, Asian societies existed in a sort of stasis because of the impacts of the state’s control of land, its military might, or how they wield irrigation. Irrigation settled people into areas with high population densities and incentivized clan-like organizational structures because those were the units that supported their early state-crafting, and after a while in place, they just kind of ‘stuck’.

In the Grundrisse, Marx described the resulting situation in Asia as individual “propertylessness” due to the “clan or communal property [that acts] as the foundation, created mostly by a combination of manufactures and agriculture within the small commune.” In these, a “part of their surplus labor belongs to the higher community, which exists ultimately as a person, and this surplus labor takes the form of tribute etc., as well as of common labor for the exaltation of the unity, partly of the real despot, partly of the imagined clan-being, the god.” In Das Kapital, he wrote that these locally-necessary economic structures supplied “the key to the riddle of the unchangeability of Asiatic societies, which is in such striking contrast with the constant dissolution and refounding of Asiatic states, and the never-ceasing changes of dynasty. The structure of the fundamental elements of society remains untouched by the storms which blow up in the cloudy regions of politics.”

Before Marx, Aristotle wrote in Politics, that the societies in the hotter regions of the world—to him, the Middle East and North Africa—were given to powerful governments. He also concluded that those north of him, in Europe proper, supported looser forms of government. I would argue more harshly than him that they didn’t really support governments, they supported tribes at the time and states with governments to speak of were rare. Regardless, he also argued that his people, the Greeks, supported more temperate and fair governance than either regime.

Aristotle was probably not just being self-serving; a read of the historical record suggests Aristotle was right. Given what we’ve discussed above, we have a probable reason why: Greece was settled by people who had adopted statehood, but in Greece, there was much less need for empires to be hydraulic ones; states persisted even without a mechanism of water control. The Greeks even built over the original inhabitants of Greece and might have adopted statehood shorn—albeit incompletely—of some of its more authoritarian cultural elements provided in the natives’ hydraulic age.

Karl Wittfogel extended this general thesis of despotic, water-based empires further, arguing that the hydraulic empire was an appropriate label for ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Hellenistic Greece, the Roman and Chinese empires, the Abbasids, the Mughals, and Incan Peru, among others. Since Wittfogel argued these states were marked by terrorizing their citizens, demanding submission, and a lack of restraint, it’s probably wise to believe Wittfogel wasn’t completely right; after all, state adoption wouldn’t have been as likely to happen if it didn’t at least benefit communities on net.

Each of these scholars had insights and issues in their theses, but they converged on something real: there was something to be explained about hydraulic empires. In the modern day, it may even be the case that these places have left a mark on the populations they ruled. For example, Johannes Buggle has argued that the more suitable regions were to irrigation agriculture, the more collectivistic they are today.4

Why Rome? Why China? Why Empire?

One of the most interesting parts of Wittfogel’s work and the work of his colleagues is how it explains China. His disciple Ji Chaoding wrote The Role of Irrigation in Chinese History, within which he argued control of watercourses was crucial to the survival of Chinese dynasties since it allowed them to control and promote agriculture, transport goods over great distances inland, and provide the government with a means of deploying troops and collecting taxes in hard-to-reach places. That seems right. Wittfogel’s colleague Owen Lattimore added to the China discussion by arguing that the history of China was also governed by interactions between the agricultural Chinese and the various Central Asian and Steppe pastoralist societies.

To begin, China’s founding mythology, like Mesopotamia’s, was also focused on taming water. Despite its geographically distinct origin, it shares many key elements with the Enūma Eliš.

In China’s deep antiquity, legend has it that the ancient sages took control of water to create order. In the myths, the pre-civilization world was overrun with rampant wilderness. Flora and fauna dominated the landscape, and a consistent deluge of unrestrained waters rendered the soil impossible to cultivate. The sages were comprised of various kings and heroes whose collective aim was to create organized civilization out of the chaos.

In fact, China has its own founding great flood myth, the “Gun-Yu myth”. Continuing:

Among the sages, Yu was most accredited for his role as a flood tamer, for establishing control over the waterways of the landscape and thus enabling a pathway for social civilization to safely emerge. To make this final step towards establishing society, Yu determined that the unchecked waters were inhibiting humans from establishing their own formal boundaries within nature. Without constant flooding, the people would be able to participate in agriculture and form the basis of society. Yu set about restraining the floods by reshaping the very land itself; in doing so, he redirected the rivers into manageable arrangements, and facilitated the development of irrigation methods.

The efforts of the mythical Yu went beyond mere canal digging and extended into natural and political philosophy. Yu’s riverine flows established the way tribute would flow towards the center of the dynastic regime and his establishment of boundaries between man and nature inspired future scholars to focus, likewise, on the categorization and distinction of natural phenomena. Moreover, the legends of Yu established that flooding was linked not so much to the sins of man, but to the illicit actions of criminals. In the stories, Yu would apprehend criminals who tried to break down the distinction between man and nature by causing floods, symbolizing the problem of resisting the orders of the state and failing to serve it well. In some of these stories, the causes of floods were quite literally leaders of deviant intellectual movements and corrupt and/or incompetent public officials.

Regardless of the historical reality or lack thereof of Yu’s Xia dynasty, his ordering of man and nature, his suggestions for dealing with floods, and his portrayal of opposition to the state as crimes against the civilized, human side of the world would stick. How many states composed that civilized, human world? The modal number is one (for 1008 years) and the average is low, with the total between 0 and 1800 AD being just 80 different states.

At the two ends of Eurasia, we have China and the West, the latter being demarcated by the Hajnal Line. The explanation for why the West had a huge number of states is simple once we understand the reason China tended to have no more than one or a handful of them. So you have a clear idea of the geography we’re looking at, here’s a map provided by Ko, Koyama and Sng:

China has some of the world’s most blessed geography for farming, replete with “river basins, fertile alluvial soil, sufficient rainfall, and moderate temperature.” The steppe, on the other hand, forced its inhabitants to be pastoralists because of its common, extensive, and extreme droughts that made stable living an impossibility. To make things worse for the nomads of the steppe, cold weather was also crippling to their food supply and when a cold snap or particularly severe drought occurred, the weather compelled the steppe nomads to organize for conflict and invasion of their agrarian neighbors so they could acquire the food they needed for survival. This conclusion isn’t based on historical inference alone, but has, in fact, been empirically demonstrated.

These invasions favored the steppe nomads decisively. China supported greater populations than the steppe could imagine, but the nomads were highly mobile in their attacks and they were capable of outflanking infantry armies due to their speed and the fact that their horses were more vigorous than the horses raised outside of the steppe environment. Critically, there was no way to retaliate against steppe nomads. They didn’t have towns, they didn’t have cities; because they moved with herds, there was nothing for sedentary populations to capture to stop them from coming. Steppe nomads effectively had what Lattimore dubbed an “indefinite margin of retreat” along the steppe’s grass highway, leaving no way to conquer them no matter how badly they could be defeated in battle, since they could ride to the Black Sea in a few weeks’ time as long as they could get away at all.

The eventual end to the threat of steppe nomads came when Russia expanded into central Asia through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. With the Russians making it impossible to retreat, the Qing dynasty was able to conquer the Dzungar khanate, finally ending the threat. Before then, they acted with near-impunity. All China could do to hold them off was keep working on the Great Wall to keep them out. This project was even a group effort before China was unified, as the first Great Wall of China was made by connecting steppe-bordering walls built by the Qin, Zhao, and Yan. Dynasties after the Qin unification repeatedly put laborers to work on this project at enormous cost to the state—it was just that necessary.

But this wasn’t that bad. These were practically the only important enemies China ever faced before 1800: all major external threats to China came from this single direction because China’s geography shielded it from the east, west, and south, and even the pirates it faced in the mid-1500s couldn’t muster anything at the level of steppe nomads. Steppe nomads could definitely be bad, but they weren’t as multidimensional as the treatment received by Europe, which included steppe invasions—from Goths, Sarmatians, Vandals, maybe Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Mongols, and Turks—of a relatively minor nature due to Europe’s forests, mountains, and distance from the steppe, but which also included threats from Vikings, Arabs, Berbers, and settled Turks. These threats were individually smaller, but they were multi-faceted and multi-sided, precluding the use of a simple, expensive strategy like one big wall.

With these facts noted, Ko, Koyama and Sng (KKS) developed a model.

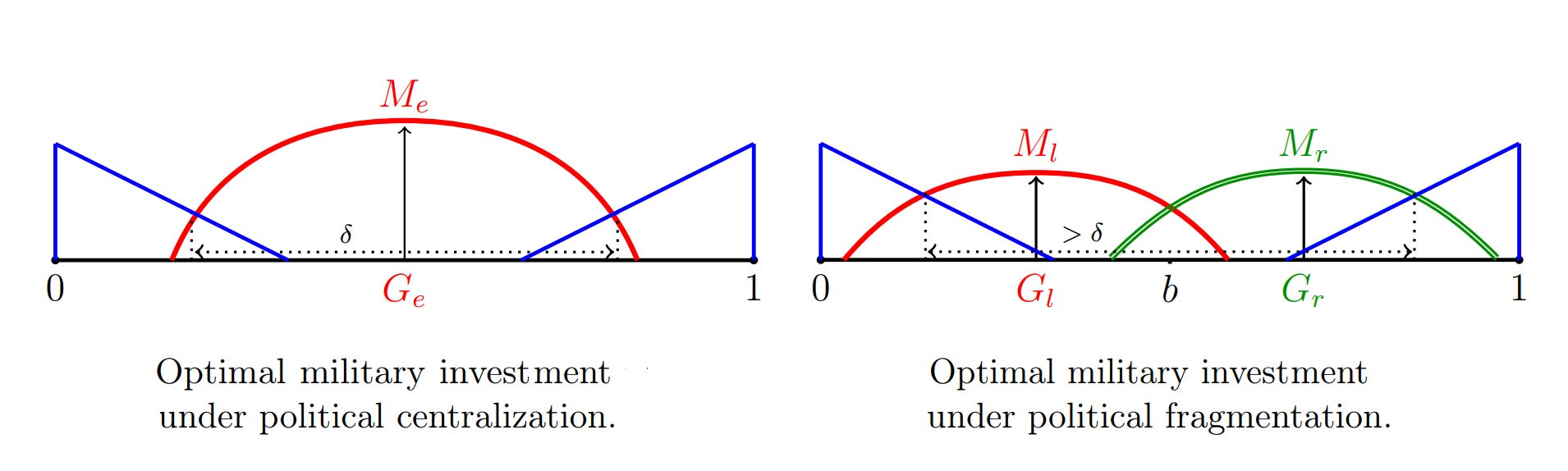

The KKS model realizes a continent as a line [0,1] with individuals uniformly distributed along it with income endowments that are taxable and non-taxable. Outside threats with a magnitude of Λ can cause gross damage of Λ at the continent’s frontiers, with gross damage for a point at t distance from the frontier being max{Λ - αt, 0}, where α > 0 is a constant used for scaling. Threats can come from one or both frontiers, there can be multiple regimes, yadda-yadda—this makes more sense if you recognize the notation and look at the diagrams:

The model implies that the ability to project military power declines with distance from a regime’s capital, so centralized empires facing unitary threats will move their capitals towards said threats since capitals are administration centers. It also implies that the borders between politically fragmented regimes will be determined by the relative balance of their projected military strengths and the demands of other external threats.

This leads us to what happens, respectively, with centralized, imperial and fragmented regimes with non-severe outside threats.

If there were no threats (i.e., Λ = 0), imperial regimes would make no military investments, as there’s no point given they can protect up to δ = 100% of the population for free. Do note: this means no internal or external threats; the possibility of revolution still necessitates military investments even for imperial regimes that don’t have external threats. If, on the other hand, Λ > 0, then interstate competition protects a larger interval of the space than a centralized, imperial regime would, because interstate competition leads to overinvestment relative to what’s needed to hold off external threats. As noted already, this theory can also predict where capital cities will be located, because force projection depends on distance from the capital.

The reason why a one-sided threat would reduce the extent of political fragmentation should be getting clearer now. A severe one-sided threat would crush fragmentary state regimes, since they wouldn’t be able to withstand both it and their neighbors. The efficiency of military projection, state administration, and so on—β—was low in the past and it decayed rapidly with distance and population—size— so centralized, imperial regimes also wouldn’t be able to withstand even small, but multiple external threats without massive, and probably wasteful investments.

Hopefully by now the picture for military investments is clear. But two more implications also need to enter this picture.

Firstly, premodern imperial regimes taxed less. This has to do with those aforementioned internal threats and the decay of β with scale. Under political fragmentation, rulers live right near you. If you cause a problem, they can beat you up at little cost to them and in little time. Under massive centralization, the emperor might be a continent’s breadth away, and if you lead a tax revolt, you might be able to secure a breakaway state for yourself with relative ease. The empire is thus incentivized to tax you as little as it can get away with because the area it has to manage—and the population in it, in the case of China—is so vast. Therefore, imperial citizens earn a tax reduction relative to those living in the fragmented west.

Secondly, the variance in population change in large, imperial regimes facing one-sided threats is greater than the variance in population in politically fragmented regimes. The reason for this follows from the graph on the right of the last set: there are multiple, overlapping sources of protection and robustness for populations in fragmented regimes, whether that’s robustness to external or internal threats, like invasions or peasant rebellions.

To briefly summarize the model’s implications:

Interstate competition wastes state resources, as if there are no threats, interstate competition still necessitates military investment;

Interstate competition is robust because is there are threats, it leads to a larger interval of a given area being protected than an empire does;

Under a sufficiently large one-sided external threat, empires will relocate capital cities away from their centers, towards threats;

Political centralization is more resilient than political fragmentation under severe, one-sided threats;

Political fragmentation is more resilient than political centralization in the presence of two-sided threats when military power projection is inefficient;

Taxation is lower in politically centralized regimes confronting one-sided threats than in politically fragmented regimes confronting two-sided threats;

The variance in population change is greater in centralized regimes facing one-sided threats than in politically fragmented regimes facing individually less severe two-sided threats.

Now, evidence.

What KKS cited for China is empirical evidence. They walked through ADL, VAR, and IV estimation exercises to explain when and why China would unify and fragment. I would add that we also have data indicating that the majority of the warfare fought in China after consolidation was definitely with Steppe Nomads:

For Europe, KKS were unable to perform the same empirical exercise because data on the number of regimes in place in given years was unavailable. For Europe, they instead described its history.

[The] closest Europe came to [being] ruled by a unified political system was under the Roman Empire. The rise of Rome parallels the rise of the first empire in China. In terms of its model, one advantage Rome had over its rivals in the Hellenistic world was relatively less convex cost function of military investment—Rome’s ability to project power and increase its… manpower was unequaled among European states in antiquity. Thus, Rome was able to impose centralized rule upon much of Europe. Our model suggests that two factors can account for the decline of Rome:

(1) Over time, Rome’s military advantage declined relative to the military capacities of its rivals such as the Persian empire or the Germanic confederacies; and

(2) These rising threats came from multiple directions along Rome’s long border.

Like episodes of dynastic and imperial collapse in China, the fall of the western Empire was associated with political disintegration and economic collapse across Europe….

In the mid-sixth century Justinian I (r. 527-565) attempted to recreate the old empire by conquering north Africa and Italy. But this attempt was short-lived. In the early seventh century, the empire nearly collapsed under the two-sided threat of first the Avers and Persians and then the Arabs. The remnant of the Byzantine empire that survived was a substantially smaller state.

In other words, ‘Rome’ the entity was predicted by KKS’ threat-based model, its demise was predicted by that model, and the failure to reconstitute it was predicted by the same model. Likewise, the attempt by the Carolingians to unify Europe would prove short-lived, as Charlemagne’s successors struggled with Magyars, Vikings, and Muslims. The East Francian Ottonian dynasty would rise in response to Magyar invasions, and it would of course create the Holy Roman Empire. But like the Carolingians, that ‘empire’s’ emperors would find their power slipping, until the Holy Roman Empire was little more than a “loose federation of German principalities” by the thirteenth centuries.

With the Viking and Muslim threats receding in the 11ᵗʰ century, Western Europe was through with multi-sided threats, but as the KKS model predicts, once you’re fragmented, that state is likely to persist without a severe external threat. That was, indeed, the case. The Mongol invasion might be considered an exception, but it didn’t last long. However, the “less dramatic but more sustained rise of the Ottoman empire” seemingly did cause a reduction in the amount of interstate warfare around Eastern Europe. As Lord Acton once noted: “Modern history of Europe begins under stress of the Ottoman conquest.” And as Murat Iyigun recorded, Ottoman warring against Europe led to peace within Europe. Feuds and conflicts between European states declined in response to Ottoman invasions, and considerable consolidation took place in sites where there was contact with the Ottoman threat.

More direct tests of the model predictions are available as well.

Capital Locations

Throughout China’s history, its capital was rarely located in the most populous provinces or in locations where there were natural defenses. Instead, the capital tended to be located in the northern or northwestern frontier regions, with China’s capital being either Changan (Xi-an) or Beijing for 84% of its unified history between 221 BC and 1911 AD. The choice of Changan (within Guanzhong, a region with 4% of the population during the Han dynasty, versus 60% who were in Guandong) or Beijing as the capital reinforces the point that capitals were located strategically to counter invasions. This is so because Changan was usually the capital in the years where invasions were more likely to run over the Central Plain, and Beijing was usually the capital in the later years, when the problematic forces were more likely to be Manchurian in origin.

Rome affirms the theory further, because its capital was not always Rome. When Rome the republic and empire was expanding, its threats were generally unidirectional, it was more likely to play the role of the conqueror, and its capital was Rome the city. In Rome’s latter years, it faced multiple external threats and it became less convenient for the capital to be Rome itself, or even its larger cities that were located towards the interior of the empire. Instead, the capital was moved to militarily advantageous, smaller cities on the frontiers. Even Constantine’s choice of Byzantium (later Constantinople) wasn’t based on it being economically significant, but on it being near the eastern frontier and the Danube front.

Taxation

China has historically had a much larger population than all of Europe. Despite this, its government only rarely collected as much tax revenue. In 1700, England, France, the Dutch Republic, and Spain combined had a population that wasn’t as large as China’s, but together, they collected 14% higher total tax revenue. In 1750, they had just 3% higher total revenues, and by 1780, they had 78% higher total revenues. On a per capita basis, the Spanish collected 275% more revenue per head in 1700 than China did in the same year, whereas France collected 418% more, England collected 884% more, and the Dutch collected more than 20 times more revenue per head than the Chinese. These ratios became more extreme with time. Even the European average in 1700 was 501% what China was pulling in. Remember this number because I’ll return to it.

The “bare-bones subsistence basket” that Allen constructed also turned out to be usable for estimating tax burdens in Europe and China, and it led to similar results: average European taxation per head amounted to 450% of the level in China: “Clearly… taxation was lighter under politically centralized China than it was in fragmented Europe.” As I’ll show later, it wasn’t just fragmented Europe that pulled in high tax revenues.

Population Cycles

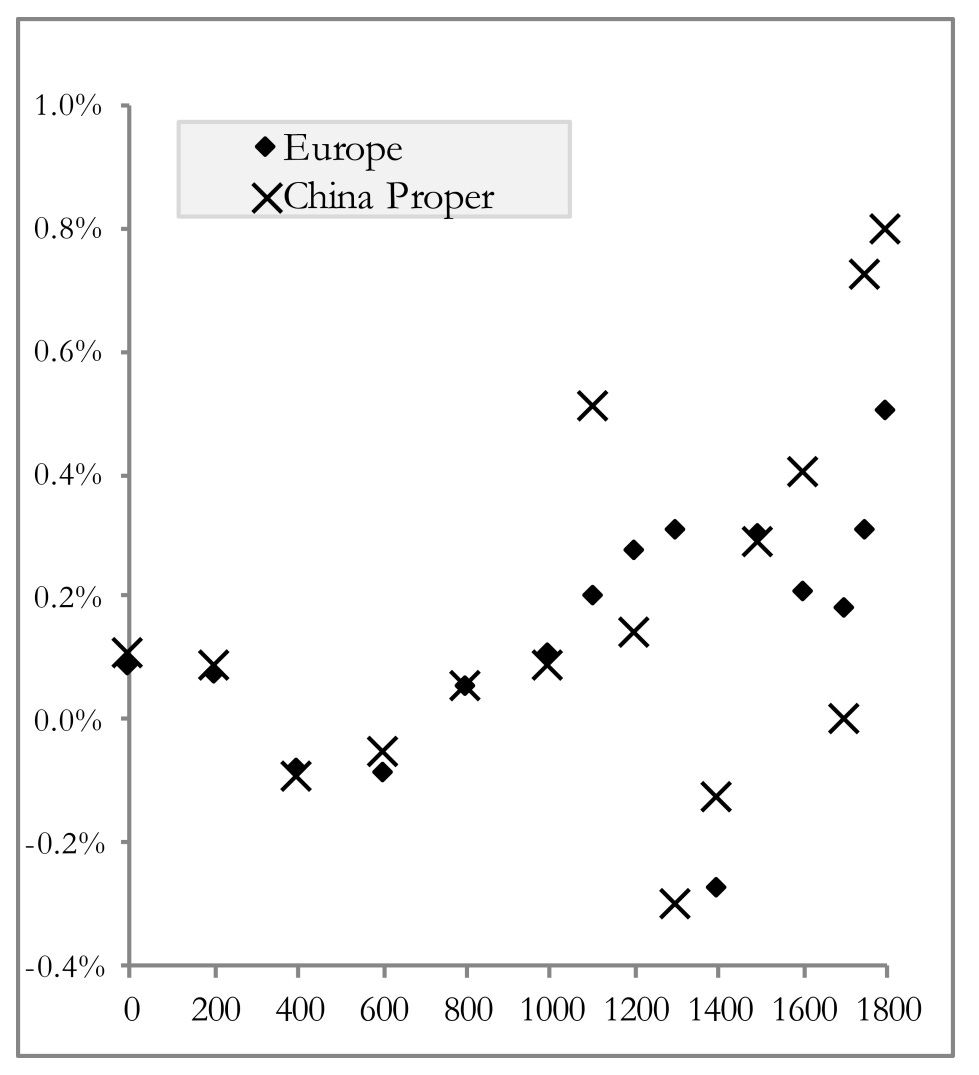

The variability in China’s population was greater than it was in Europe. The fragmented regime did better prevent threats from impacting aggregate European population growth, and multiple sources seem to affirm this belief. For example, the low-frequency population data from McEvedy and Jones does this.

The more high-frequency data from Cao tells a similar tale, but very clearly shows population contractions related to the falls of dynasties:

Put differently using the McEvedy and Jones data, we can see that China and Europe grew in tandem when they were both centralized, but when Europe fragmented, their annualized growth trajectories split apart:

It is simply easier to fit a line through European population estimates than it is to fit a line through Chinese ones because the Chinese ones change erratically in response to known exogenous shocks. Using the official historical records from China reveals the same story to a more extreme degree, but this is likely a contaminated estimate because records should drop in quality during dynastic collapse. KKS remarked that a “substantial amount of this population ‘loss’ [in the official historical records] was likely due to the state’s inability to keep accurate records during times of crises instead of actual deaths.” Either way, the reconstructions and official records agree in direction, if not over matters of magnitude. As a final contrast, Europe only suffered one major population decline after fragmenting: the Black Death.

Dovetailing Alternatives

There are certainly other parts to the stories of China and Europe, but popular alternatives do not really threaten this one. Nomadic incursions Granger-caused political unification in China, but they weren’t the only factors at play, nor does the KKS model claim they are. For example, the explanation that “European (Chinese) geography was less (more) conducive to political centralization due to the presence (absence) of irregular coastlines and mountain barriers such as the Alps or Pyrenees” fits squarely within this one as a reinforcing factor. Likewise, institutional-cultural-religious factors such as the imperial examination probably reinforced China’s centralization, while the papacy actively sought to limit the size of states and the interconnectedness of families to hamper competition for secular power in Europe.

As KKS noted, several other scholars’ cases strengthen theirs:5

While the presence of multi-sided threats could shed light on why Europe was fragmented in the Middle Ages, our argument cannot explain why the number of states in Europe continued to rise after 1100, when external threats to the continent subsided considerably. Tilly addresses this, arguing that the presence of independent city states along the corridor between southern England and northern Italy prevented the emergence of large empires in Europe at the end of the Middle Ages. More recently, Hoffman also suggests that the Catholic Church played a crucial role in preventing first the Holy Roman Emperor, and later the Habsburgs, from dominating Europe.

However, Tilly’s theory does not explain the existence of independent city states in late medieval Europe, which was a legacy of the collapse of the Carolingian empire. [Citing Pirenne!] Similarly, Hoffman takes as given the papacy’s rise to secular authority in medieval Europe—a phenomenon made possible by the existence of numerous rival kingdoms and the absence of a legitimate and powerful European hegemon in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. In this regard, our argument complements the above theories by highlighting how Europe’s external threats contributed to its political fragmentation before the eleventh century. This “initial” fragmentation then proved persistent because the absence of a single long-lasting hegemonic state made it easier for the Catholic Church to entrench itself as a genuine rival to the secular powers of Europe and allowed small independent city states like Genoa, Florence, and Venice to emerge and contrast the power of territorial states.

In the same way, Ji Chaoding and Owen Lattimore seem to have both explained China.

Why China Lost the Mandate of Heaven

The questions of why Europe industrialized before China and why anyone industrialized at all are important historical questions that remain unanswered. Though they’re not formally answered, I think the broad strokes behind why China fell behind are now known.

Recall that China was a hydraulic empire, unified in no small part so a central government could service major subsistence infrastructure projects and provide for the common defense of an enormous realm against essentially just one serious threat. The reasons for its enormous population variability also do not solely follow from invasions, but also from internal failures, and China’s large size practically ensured that those failures would happen.

Remember the tax figures from KKS? The per capita tax revenue in 1700 for China was 10.4 silver grams. By 1760 or so, the Great Qing had reached their greatest geographical extent, and during that upswing, they managed to extract more per capita tax revenue, reaching 11.8 silver grams per capita in 1750. But with their greater size and higher total revenue, by 1780, that figure had reached 9.2 silver grams per capita.

This is probably explained by many factors and it’s certainly not a large trend in this instance, but there is probably something significant to say about the evolution of taxation over time in different regimes like the one found in China and those found in Europe. Consider per capita tax revenues in early modern China and Japan:

Over time, China’s tax revenues fell, while Japan’s remained much more stable. I’ll contend that this dynamic characterized both regimes more generally. As time advances, the Chinese state generally sees its revenues fall, reducing its capacity to maintain infrastructure, spend on the upkeep of the military, and provide other crucial state services. Contrarily, in fragmented societies like Japan and Europe, the fragmented states are more capable of reliably taxing their citizenry because—as we know—state capacity decays with scale. This explains why China had lower revenues in general, but it doesn’t immediately explain why they would tend to decline with time or why they would be reset.

The thing that explains why China’s state would become less effective at taxation and every other state service in tandem as time goes on is the accumulated harms of the large-scale presence of principal-agent problems. Several scholars have attested to and found evidence for this issue, whereby the principal—the emperor, the imperial center, etc.—is poorly-represented by its agents—tax collectors, mayors, regional administrators, bureaucrats, etc. Given China’s scale, duties had to be delegated through bureaucracies

Because rulers couldn’t monitor the Chinese realm due to its size, they needed to keep taxes low, but the agents of the rulers had the opposite incentive: because the ruler couldn’t monitor them, they might as well extort as much as possible in the name of the emperor. As this theory predicts, the further from the capital, the more lax the taxation regime. Some scholars have even theorized that China intentionally allowed some level of graft by local officialdom in order to keep the peace.

Even though its efforts would ultimately prove to do little, China did try to prevent corruption. Officials were audited, people were assigned to positions with loyalty in mind, and systems such as the Keju imperial examinations allowed China to identify, recruit, and distribute talent in ways that benefited state capacity in various ways.6 But these systems didn’t exclusively work in the state’s favor. For example, a greater number of major officials that came from a prefecture, province, or county slowed the rate of adoption of the Ming’s Single Whip.

Try as it might, China’s realm declined in power, prestige, and stability as time advanced, and it recovered after crises like the Taiping Rebellion7, floods, invasions, and so on provided opportunities to do massive shake-ups to its bureaucracy. But in many cases, these shake-ups only happened when the next dynasty took over. In other words, this dynamic reinforced China’s dynastic cycle, whereby it existed in a state of either despotism or anarchy, and when the despot became weak, it quite literally felt like the world was ending.

Dynasties lost the Mandate of Heaven cataclysmically. Because the imperial state maintained canals, levees, and the allocation of corvées, maintenance failures led to natural disasters in the form of massive floods, and particularly, violent Yellow River floods. The reason the world appeared to end to so many millions of people when dynasties fell was that dynasties artificially propped up many elements of everyday Chinese life—as the Yu the Great stories illustrate—and their failure to keep propping up the requirements for subsistence in China was a massively discrediting indictment. It’s no wonder new dynasties kept taking the reins after the old ones lost the Mandate of Heaven.

What this has to do with why China fell behind the West is actually very clear when we understand one more fact: in the premodern world, where technological know-how was stored in people’s minds rather than in easily-accessible tomes or computers, population change asymmetrically impacted the aggregate amount of knowledge a society had. This is because of the little-discussed phenomenon of technological regress.

In the premodern era, populations would technologically progress as they grew, but when they shrank, living conditions frequently worsened enough that people would be forced to give up using, working on, and transmitting newly-learned techniques and newly-minted technologies in favor of simple farming, and the knowledge related to those things would be lost to subsequent generations. Likewise, the demand for new technologies and techniques would fall, and those who knew them would fail to transmit them to the next generations because there’s no time or need. When those subsequent generations reversed the declines that caused people to drop new technologies, they wouldn’t be able to just pick them up again, so their productivity growth rate over the years would almost-certainly have been negatively impacted relative to the counterfactual where the division of labor hadn’t shrunken.8

The storage of knowledge in the premodern era was also very lopsided towards elite individuals because it had to be. Books? At least in Europe, these were rare and expensive. Education? So costly it made the Jizya seem like a pittance. Apprenticing? This takes time, and the premodern era was frequently Malthusian, so downturns were very often life-or-death. For that reason, if there’s a serious economic downturn because of steppe nomad invasions or a dam breaking, expect people to move away from skilled trades and more towards the sorts of unskilled farm labor required to survive at all. In other words, transmitting elites’ knowledge en masse was generally infeasible. If a natural disaster or invasion took them out, it’s likely whatever discoveries they made wouldn’t be transmitted to subsequent generations, or at best would be unreliably transmitted.

As we’ve seen, this implies that fragmentation decisively advantaged Europe. Aiyar, Dalgaard and Moav described this phenomenon with other examples, like the loss of Easter Islanders’ knowledge of how to make Moai or the loss of the Romans’ knowledge of how to build large baths:

Consider for example the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. The bath building was huge: 228m long, 116m wide, and 38.5m in height. It could hold an estimated 1,600 bathers, and the complex covered about 13ha featuring sumptuous decorations. This entire structure was erected in a mere 5 years, between A.D. 211 and 216. After the fall of the Roman Empire, however, we find an apparent cessation of construction in fired brick (and concrete) north of the Alps from about the fifth century.

Declining demand undoubtedly played a crucial role in explaining this fact. Temin, for example, argues that the standard of living in ancient Rome likely was comparable to that of 17th and 18th century Europe; this would suggest a major demand contraction in the aftermath of the Empire’s collapse. As a result, construction simply did not take place on the scale and frequency of earlier times, making the quasi-industrial organization of the sector unprofitable. This would explain the loss of such a basic technology as fired brick; the technology was no longer profitable, and was therefore not practiced and transmitted. Technological regress was the consequence. In fact, fired brick was by all accounts not used again in construction (in the Northern part of Europe) until the first half of the 12th century. With fired brick we also see the loss of Pozzalana cement.

The consequences for productivity in construction were considerable. Whereas major undertakings such as the Baths of Caracalla or Diocletian was completed in less than a decade, Medieval Cathedrals, such as Laon, Notre-Dame, and Salisbury often took 50-100 years to complete, albeit of comparable size to the baths of Rome. The root cause was a marked reduction in the division of labor, brought on by the demand contraction, which ultimately led to the loss of important technologies like fired brick and Pozzalana cement.

Elites build productivity-enhancing knowledge slowly and lose it quickly. China was institutionally set up so that it often lost elites and disincentivized remembering new techniques and technologies. For this reason, fragmented Europe managed to slowly lurch ahead despite China outgrowing it in terms of population; while China might have out-learned Europe, China also forgot more than Europe.

From Caveman to Chinaman

Man started farming because the motions of Jupiter pulled the Earth into a stellar situation that made proto-farming desirable and, from there, it was a hop and a skip to real farming. Farmers established states to make life possible when nature threatened their ability to farm. After the Chinese state unified, it tended to stay unified because of the constant threat of steppe nomads invasions. Finally, the unity of China was its downfall because premodern state capacity was limited in ways that disposed its dynasties to massive population shocks that critically impaired the process of knowledge accumulation.

Historical contingency set China on a path for failure, and that is why the West won.

A Fun Aside: Quesnay and Montesquieu, or

Despotism (Boo!) and Despotism (Hurrah!)

[In Europe, in contrast to Asia] strong nations are opposed to the strong; and those who join each other have nearly the same courage. This is the reason of the weakness of Asia and of the strength of Europe; of the liberty of Europe, and of the slavery of Asia. — Montesquieu, De l'esprit des loix

Montesquieu’s views on China and the tyrannical nature of law in Asia more generally have been massively influential to many thinkers. But contrary to his theory, the government of China was generally quite lax. Compared to Europe, commerce was minimally regulated and the citizens tended to be taxed much less while receiving a larger basket of state services, from calendars to the opportunity to enter into the state’s civil service through testing that was usually demonstrably fair.

So, in what way was China more despotic than Europe? Why would the Chinese be slaves and Europeans be free men? I’m not alone in asking this question. In Montesquieu’s time, the Physiocrats penned the same question. Montesquieu’s contemporary François Quesnay actually went in the opposite direction and posited that China was freer and France ought to emulate her in his La Despotisme de la Chine. He praised China’s constitutional despotism, standardized taxation, universal education, meritocracy, and other aspects having to do with China’s relatively free commerce.

I think we can say that the difference is two-fold. Firstly, Montesquieu exaggerated the situation in Asia. In many ways, the average person in China was more free than the average person in Europe. But secondly, China was arbitrary; because China was such a large domain, officials could do things like doling out capital punishment without fear of peasant insurrections, resistance, or anything to do with comeuppance. The scale of China encouraged graft and made it so that the oftentimes evil, but individual actions of the Chinese state were not all that bad for the stability of the realm. If you governed a European microstate on the other hand, you were probably better insulated from arbitrary injustice at the hands of the government, but you would have tended to be less insulated from the routine injustice of living under a tyrannical government that is so because it’s capable of being so due to its small size and the scaling constraints of premodern state technology.

Montesquieu and Quesnay were both right about Asia in different ways.

Jebel Irhoud is 315,000 or so years old, but it is only debatably modern and is often considered to be proto-modern, including by Chris Stringer as of early-2021. Omo-Kibish could easily be more than 233,000 years old. Ultimately the precise timing of the rise of anatomically modern humans so far back is irrelevant for this article.

Precipitation seasonality was also directionally related to the advent of farming, but it was less consistently statistically significant. This seems like a statistical power problem.

Additionally, the authors showed countered the potential objection of this being human-led by showing that “our first river shift does not correlate with lagged human activity, suggesting an exogenous and geographical origin for this shift.”

Three notes.

First, be cautious about the exact levels and rank orders of collectivism measurements across cultures. Their meanings are also debatable.

Second, check out this cool paper that argues historical agricultural suitability predicts long-term time orientations in the modern day. Related to this, Europe doesn’t really need to be a hydraulic empire because it has ample rains. Irrigation just isn’t necessary, and that makes the value proposition for large empires that much worse in Europe, while also making would-be empires that much weaker because they wouldn’t have water control.

Third, check out this cool paper that argues that historical climactic variability predicts trust in the modern day, at least within Europe. Caution about the trust measurements’ comparability and meanings is warranted, but the result at least makes intuitive sense.

I think the same thing about other things I’ve written here, I just haven’t written every little thing that could go into this post, and I wouldn’t want to.

Including funneling talent into the state instead of maintaining it outside of it where it can cause problems, and giving people a more positive view of the state thanks to the appearance that the Keju was mobility-promoting.

Moving talent into the state’s orbit via the Keju and accordingly away from commercial enterprises might also be considered a downside of the system, since it might have been the case that work in the state would be less productive than the work smart people could have been doing outside of it. Similarly, in modern-day China, the state receives many of the most talented youngsters and there’s little doubt they could be more productive in the private sector.

The Qing actually discovered additional, indirect revenue streams after the Taiping Rebellion, like customs duties levied on foreign commercial activity.

This is not to say that there cannot be good things to certain collapses or population declines. For example, the Black Death arguably shook up sclerotic institutions that held back development in Europe, making the losses to knowledge and population that it directly yielded worth it in the longer run. This is not clearly the case in China, whose institutions seemed much more static, likely due in part to their nature as a hydraulic empire facing a severe one-sided threat.

This was a superb read, thank you. Are you by chance familiar with Scheidel's Escape From Rome? He deals with much overlapping themes of European comparative prosperity and China's hardships with centralisation and steppe hordes.

The book argues that the fall of the Roman Empire and the resulting political fragmentation in Europe was the best thing that ever happened to us. It fostered competition and innovation, leading to the region's eventual economic and technological sucaess. Unlike centralised states like China, Europe's divided states encouraged military and technological advancements, preventing monopolisation of power. This fragmentation laid the groundwork for capitalism, scientific progress, and modern political institutions, making the collapse of Rome a crucial turning point for Europe's prosperity.

I found many, many same things mentioned in this post as was in the book.

I couldn't help but be reminded of Taleb's theory of anti-fragility. It seems The West was more anti-fragile because of its diverse geography and the multi-variate threats against it, while China was bigger and better organized but ultimately more susceptible to frequent( every hundred or occasionally more years) Black Swans because of its geographical unity and the uni-dimensional nature of the threat from nomads.