Beware the Man of Many Studies

Low-quality literatures mean meta-analyses are frequently worse than single studies

In 2014, Scott Alexander penned a post that has been widely-cited ever since. He described something everyone can agree is a problem: placing too much trust in singular studies instead of the results of literatures.

In turn, he emphasized the need to do a few things. For one, seek out comprehensive summaries of all of the evidence on a particular topic, like a high-quality funnel plot. For two, think about how results may need to be qualified. In his minimum wage example, the effects estimated in different studies could have differed for reasons besides the ideology of the economist behind the study. They might have depended on the size of the change in the minimum wage, the region or industry the change affected, or the time the change happened. Finally, be less confident about results, beware the conclusions of people who are clearly biased, and beware the conclusions of people who appear to be presenting a very strong case until you’ve done some research of your own.

But this isn’t enough. Sometimes literatures are corrupted. Scott wasn’t unaware of this; he did provide a passing mention of fraud and publication bias. But the problem is more extreme. This post briefly discusses why it is often better to trust a single study than a whole literature.

Publication Bias

Publication bias occurs when some results that belong in a literature are systematically more likely to be published than others. This can happen for many reasons, like editors preferring flashy results and flashy results having something in common like very large effects or using diverse samples.

One of the more common ways it happens is through filtering for significance. Authors know the public and journal editors do not want studies that did not produce significant results1, so there is an incentive to only submit a study when the p-value is below 0.05. This also creates an incentive to take results that are not p < 0.05 and adjust them, whether through residualizing for enough covariates, filtering sample observations, or checking results in subsets. The point is to find some permutation of the data that produces p < 0.05 that can thus be considered worthy of publication.

There is a particular effect that is the smallest you can detect with a given sample size. Because of this, if your sample is small enough, your effect must be very large.

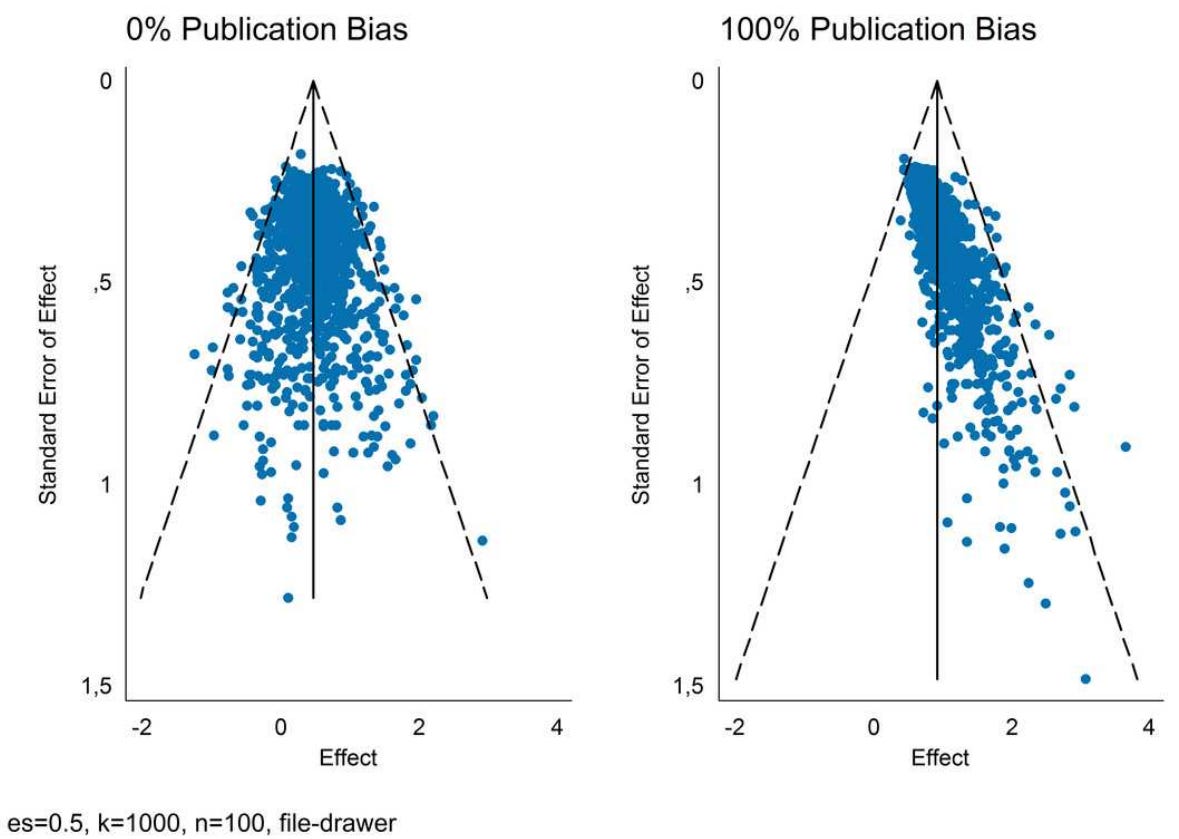

The selection for significance and the dependencies between p-values, sample sizes, and effect sizes combine to give birth to the publication bias pattern, the consistent observation that effect sizes in many literatures are larger the less precisely they’re estimated. If you’ve read me before, you probably know what this looks like, but if you don’t, here’s an example provided by Andreas Schneck:

In funnel plots like these, the publication bias pattern is readily visible. The effect on the meta-analytic estimate is also quite clear: because of the large number of studies that have estimates that are too large because they weren’t precise enough, the effect seems to be much larger than it really is when there’s bias!

Many literatures actually look like that plot on the right. Consider two examples: air pollution effects on various outcomes and mindfulness effects on students outcomes.

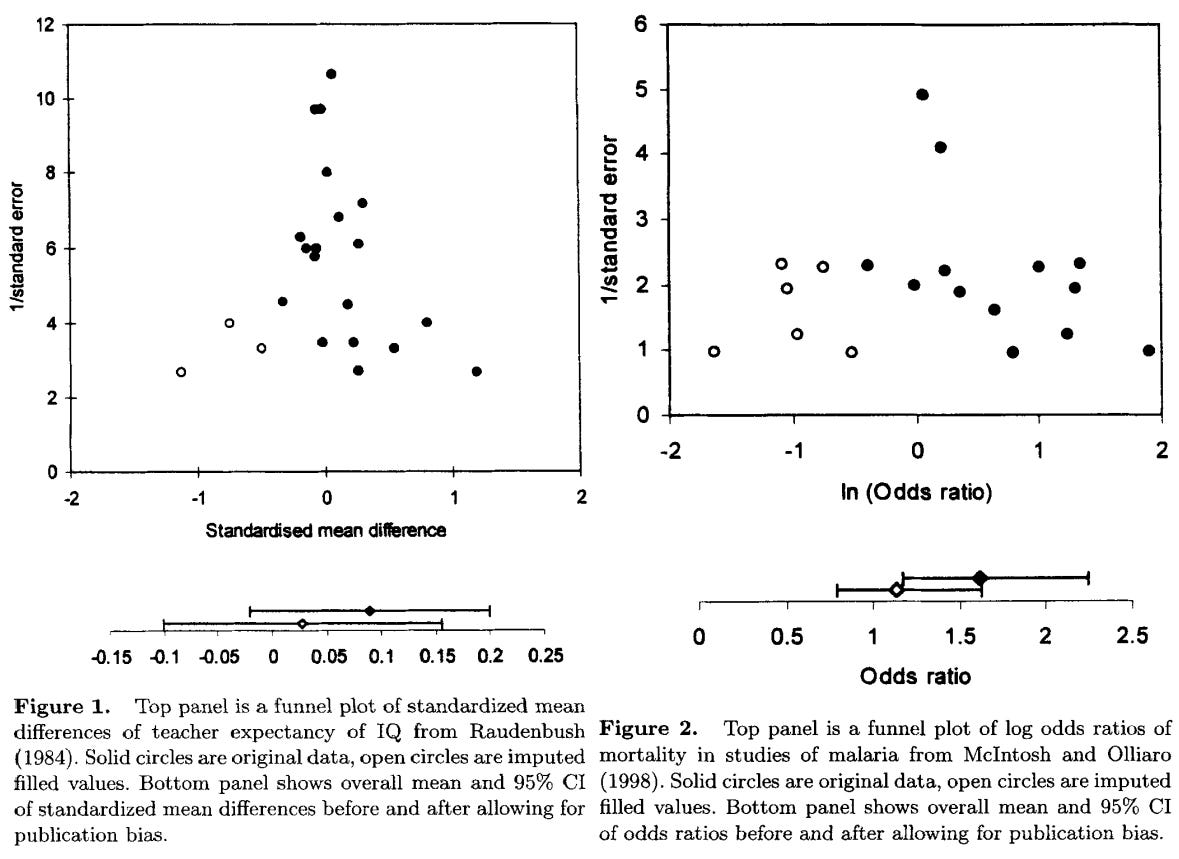

The trim-and-fill method is a ready-made way to correct this bias by adding datapoints that mirror the observed asymmetry in the plot on the other side of the meta-analytic estimate. The original examples makes it pretty clear how this works. In these figures, the “filled-in” estimates are the empty white dots and the black dots are the estimates that were observed in the meta-analyses. After adding the white dots and effectively limiting the power of the imprecise, outlying results to exaggerate the meta-analytic estimate, the new estimates are greatly reduced. There are many more severe cases where estimates become entirely null after correction.

There are other publication bias correction methods like PET, PEESE, PET-PEESE, p-curve, and three-part selection models. The only problem with these methods is that they only work when the number of studies is larger, the publication bias pattern is observed because of a filter for significance, and when the pattern is weak, but not so weak that the algorithms for bias correction don’t recognize points as requiring correction.

We know this is true because we can simulate it and because it has been empirically tested. The empirical tests show very poor results: every method tends to undercorrect the meta-analytic estimate. On the left-hand side, you have the meta-analytic effect size and right next to it, you have the effect size from large, preregistered replications. The yellow columns represent the effect sizes obtained when the meta-analytic estimates are adjusted with PET-PEESE — a correction many consider too conservative — 3PSM, and trim-and-fill.

This point is not unique. My favorite replication showed an incredibly visible publication bias effect in the literature on money priming. Note the results for published and unpublished studies. One was clearly larger and more biased than the other. Interaction effects, which are harder to detect than main effects, were also subject to very notable publication bias. Because of the low power to detect them, preregistered studies probably didn’t even attempt to look for them either. And finally, pre-registered effects were centered precisely around 0. Money priming is not real. Like many effects that build extensive literatures, it was an invention that was built by publication bias.

Some of the publication bias pattern happens due to minimal filtering for significance, simply shooting for a p-value less than 0.05, and just under 0.05. As I’ve written elsewhere, this leads to a bump in the distribution of p-values so that there’s an excess right below the threshold for significance. But it doesn’t have to be this way, and that weakens publication bias corrections. This occurs when people perform their p-hacking — knowingly or otherwise — in a way that creates an effect that is extremely significant rather than just significant.

Sometimes something similar to the publication bias pattern crops up for reasons that are not publication bias. This is what happens when an intervention fails to scale. Because scaling failures could lead to a lower expectation for future effects, they may actually be a good thing if they lead to power analyses that are more conservative and either suggest the need for larger samples or more funding per person. But if larger samples result in smaller effects because of scaling issues, this can be a self-reinforcing problem. Because of this, differentiating publication bias from a scaling failure can be difficult and requires large, preregistered replications to provide a credible adjudication between or qualification of different explanations.

One thing is certain though, and it’s that scaling failures should not produce results that are just significant or which appear to produce a bump below significance thresholds. Scaling failures without publication bias should lead to results that are not significant rather than just significant. They could augment the risk that p-hacking happens, but this means scaling failures should be thought of as a promoter of publication bias rather than a complete alternative to it.

Because of how often preregistered replications vindicate the explanation being largely or entirely publication bias, I tend to expect it to explain results far more often than scaling failures do.

Sometimes neither scaling nor publication bias are the reason for a pattern that appears to be consistent with either at a first glance. This happened with educational interventions that had required reporting, preregistration, and outsider analysis as conditions to receive funding. You can see that in this plot of studies funded by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) and the National Center for Educational Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE).

This plot is worth careful inspection. The dashed line represents the minimum detectable effect size for a particular trial. You can see that there’s a publication bias pattern of sorts, and if you click into the study you’ll see it looks more typical in Figure 2.

So what’s going on? This looks different from publication bias, typically-construed, because very few of the studies that provided the basis for the pattern actually produced significant results. They were not p-hacked; they were just not significant and appeared large because imprecise null effects are tautologically more likely to be outrageously large than precisely-estimated null effects.

This study found that the year of publication, the quality of the trial, the cost per pupil, and the total cost of the trial weren’t moderators of the effect sizes of these trials. The only moderator that mattered was theoretically expected and it was the difference between efficacy and effectiveness trials. The former are trials conducted in ideal conditions and the latter are ones that are conducted in realistic ones. The difference was very minor but it went in the expected direction: a mean effect of 0.05 for efficacy trials and 0.01 for effectiveness trials.

These trials were all large, well-funded, and conducted remarkably well for their field. The publication bias-like pattern happened because of the inherent likelihood of extreme estimates in imprecise studies coupled with the selection of studies for funding. To obtain funding, researchers had to submit evidence that their method would work, so there was a bias towards funding interventions that were at least likely to not cause harm. Despite this, the evidence for any effect was basically zero across all of the studies; the power was also low, with a median of just 17%, which suggests that the relationship between power and the publication bias pattern is due to p-hacking since it wasn’t actually observed among these studies.

So we have a problem: meta-analyses can sometimes suggest but often cannot address the issue of publication bias. If you trust uncorrected meta-analytic estimates, you will be misled. If you trust corrected meta-analytic estimates, you will often still be misled.

Dependence on Low-Quality Effects

Studies vary in their quality, but until you’re doing moderator analyses, your meta-analytic estimate treats studies as if they’re all the same quality. All it takes is your estimates and your standard errors, and the result you get is the weighted estimate of the effects across studies that can wildly vary in how trustworthy they are.

The weight for a study with 10% power will be based on an SE just like a study with 80% power. If the majority of studies have low power, they may have less individual weight than more powerful studies, but they will still tend to drag the estimate towards where they are rather than towards where the powerful estimates are. If they’re in the same place, no problem; if they’re systematically differentiated with less powerful studies producing larger effects, as they tend to, you may have a problem.

Low power is the norm for almost all fields, including neuroscience, political science, environmental science, medicine, or breast cancer, glaucoma, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s research. When performing a meta-analysis, you are almost certainly working with underpowered research, and meta-analytic results will reflect this. Meta-analysis and corrections for publication bias will only be able to go as far as the provided data allows, and if the quality is low enough, all that can be obtained is a biased and unrealistic result.

As noted above, no amount of correction solves these problems. “Garbage in, garbage out” is a problem that meta-analysis cannot solve; to get around it requires new studies, not the tired reanalysis of garbage. But if one decides to check the effect of study quality as a moderator of meta-analytic effects, they may think they can handle quality issues. How well they’ll be able to do depends on how well they’ve coded study quality with respect to how dimensions of study quality varied with respect to the estimate used in the meta-analysis.

A typical way to code study quality is to make a checklist of things that denote higher or lower quality and then to give each study a score that denotes their quality. But let’s say study quality varies within items on a quality checklist, some items matter much more than others, and some items deemed relevant to quality don’t matter at all. It may be impossible to know a priori how one should weight study quality dimensions, whether the effects of those dimensions on estimates are sufficiently accounted for by the coding, or even if the resulting estimate is biased

So researchers may decide to assess the moderating power of individual dimensions of study quality. Again, the validity of the assignment of quality scores may be lacking, scores may not be granular enough, the coding may be insufficient, and the separate analysis of dimensions may obscure details that require a fuller simultaneous modeling of study quality. With the small number of sample sizes included in typical meta-analyses, this problem is exacerbated by random error in addition to whatever systematic errors pop up in the coding process. Researchers must be lucky for moderator analyses to work. The exceptional dimensions are for things that are obviously independently relevant to study quality, like whether there are passive or active controls in an experiment. When a moderator is something that is due to sampling (like age) rather than study design (like controls for the placebo effect), it is more likely to leave or promote endogeneity concerns.

I can go on about other ways to do this, but they all reach the same tired conclusion: meta-analytic estimates can only be moved so much by correction and moderation, and any changes to the estimates will usually be of uncertain utility. This cannot obviate the need for replication.2

Heterogeneity

Scott mentioned the example of minimum wage effects. The literature on minimum wages is one that is minimally amenable to meta-analysis because its effect sizes hinge on important moderators. A meta-analysis that finds a null across all studies probably omits important details, like that minimum wage effects are broadly beneficial when there’s lots of monopsony power, or that the minimum wage is less deleterious when it’s raised by a little bit rather than by a lot.

Because these important qualifiers may not be accessible as often as minimum wage studies can be published, a null may be the result of the typical study without an important effect of those moderators being more common. A meta-analysis treating the typical and the exceptional study alike will obscure important, policy-relevant identifying variance. If researchers have an ideological bent, a meta-analytic null may just be an expression of the typical sentiments of researchers. It doesn’t take many biased people for this to be true even if every analysis is completely internally credible.

For meta-analyses that are more naturalistic and less standardized like minimum wage studies, there will always be something to dispute. You cannot be a man of one or all the studies when it comes to the minimum wage because too many studies say importantly different things despite fitting under the broader banner of being “minimum wage studies”.

When heterogeneity matters, you ought to be a man of several (but likely not all) studies or a review that credibly compiles them and shows an understanding of the nuance that goes into understanding them all in concert.

What about literatures where the things that produce effects are relatively homogeneous and the things being affected are too? In those cases, you might still need to be a man of one study rather than the man of all the studies. For this example, I will use the effects of income or wealth on mental health and I will use lotteries to identify the effect free of confounding, because lottery wins are random for the individuals who play them.3

Lindqvist, Östling & Cesarini (LÖC) recently published a far better estimate of the effect of lottery wealthy on psychological well-being than the entire literature published before their study.4 Their study had a larger sample than most of the prior literature, it had more variation in the size of wins and thus more identifying variation, it had a more representative sample of winners, and it had the most years of coverage among published studies. Simply put, it was by far the best study on the effects of lottery wins on psychological well-being.

Let’s compare it to the prior literature. There were four studies to speak of that came before LÖC. Look at their results versus LÖC’s:

These effects are so extreme relative to LÖC’s and the effect of income in the general population that they obscure the standard errors for both of those estimates. In the general population, $100,000 is associated with 0.068 SDs (SE = 0.009) better psychological well-being. In the prior literature that I meta-analyzed, the effect of $100,000 was consistent with 0.873 SDs (0.443) better psychological well-being. By contrast, LÖC’s estimate was 0.013 SDs (0.016).

The effect of $100,000 on psychological well-being appears to clearly be confounded and is unlikely to be causal based on a design that is very well identified.5 But if you had used the prior literature, you would find a different result: a major effect of lottery income and at the same time, no difference from the relationship in the general population. You would be misled by using all the available studies.

The number of available studies was small, but the point applies generally because it’s not that unrepresentative of what happens with literatures that are full of tons of studies.

Fraud

Sometimes studies are fake, and fake studies pollute meta-analytic estimates. A man of all studies sometimes may not survive fraud. If he considers a fraudulent study to be representative of a wider literature for an effect he’s interested in, he’ll be misled.

You can see this in the relationship between motivation and IQ testing. In the latest meta-analysis of whether motivation can enhance IQ testing results, Duckworth et al. (2011), three of the studies were by convicted fraudster Stephen E. Breuning. The three likely-fraudulent studies were among the largest in the literature, they had some of the largest effects, and they were estimated more precisely than the rest too. They made it seem like there wasn’t any publication bias, but if you remove them, every standard publication bias correction suddenly turns the meta-analytic estimate into a null.

How many studies are fraudulent? It’s unlikely that a large proportion of studies are completely fraudulent, but many have some degree of fraud involved, even if it’s the result of something as simple as incorrectly rounding a p-value, effect size, or standard error by a small amount that could, potentially, add up to an incorrect meta-analytic result.

Spend a few hours scrolling through Elisabeth Bik’s Twitter and you may come away thinking everything is fraudulent. Who really knows?

Peer Review Hardly Applies to Individual Studies

Scott mentioned the “magic words ‘peer-reviewed experimental studies.’”

Peer review is not magical. If you’ve ever participated in it or been the subject of it, you’re probably aware of how bad it can get. As many have recently learned from the preprint revolution, it also doesn’t seem to matter for publication quality. The studies I mentioned in the previous section on fraud all passed peer review and it’s almost certain that every bad study or meta-study you’ve ever read did too.

The cachet earned by peer review is undeserved. It does not protect against problems and it’s not clear it has any benefits whatsoever when it comes to keeping research credible. Because peer review affects individual studies heterogeneously, it can also scarcely make a dent in keeping meta-analyses credible. The meta-analyst has to trust that peer review benefitted every study in their analysis, but if, say, a reviewer preference for significant results affected the literature, it could have been the source of publication bias. A preference for any feature by any reviewer of any of the published or unpublished studies in a literature could be similarly harmful. Significance is just one feature that there’s a common preference for.

When it comes to reviewing meta-analyses, peer reviewers could theoretically read through every study cited in a meta-analysis and suggest how to code up study quality or which studies should be kept and removed. Ideally, they would; realistically, when there are a lot of studies, that’s far too much to ask for. And you usually won’t know if it could have helped in any individual case or for meta-analyses because most peer reviews are not publicly reported. Peer review is a black box. If you don’t take expert’s words for granted, why would you trust it?

Peer review is simply not something that helps the man of many studies. At best, it protects him when the meta-analysis is done poorly enough that reviewers notice and do something like telling the researchers being reviewed to change their estimator. If they tell them to seek publication elsewhere, the researchers could keep going until they meet credulous enough reviewers and get their garbage published.

Because of how little evidence there is that peer review matters, I doubt it helps the man of one or many studies often enough to be given any thought.

A Final Thought

Like Scott, I do not want to preach radical skepticism. I want to preach scientific reasoning. If you’re interested in the research on $topic_x, you should familiarize yourself with the methods of that field, and especially with the field’s most critical voices. You should know what’s right and what’s wrong and be able to recognize all of the issues that are common enough for the field’s researchers to see them with a sideways glance.

Most people are not equipped to do this. When they are, they may not know they’re capable; when they’re not, they may wrongly believe they’re capable. Scott’s recommendation to decrease your confidence in claims is good, avoiding biased people’s conclusions is also good, although I would like to add that biased people are good to read to understand flaws in the arguments of the people they oppose, and the need to look at all of the evidence is still quite obvious.

I want to add that thinking about causal inference by focusing on designs is necessary to build a proper understanding of science in general. One well-designed, high-powered study is often much more valuable than a vast number of more poorly-identified and lower-power studies. This is so true that the man of one study who knows he’s the man of one study because the rest are garbage is often much less wrong than his peer men of many studies. Because it’s hard to convey that he is the man of one study who knows he’s the man of one study, that may be hard to see.

This can be reasonable. If editors did not have a preference for significant results, they might find themselves publishing underpowered null results.

This was a point made frequently by Hans Eysenck.

There are many examples where this happened. For example, I showed that this occurred in an earlier post on the effect of gas stoves on asthma rates. The meta-analysis that produced an effect size that caused a lot of alarm ended up being a huge overestimate due to a combination of coding and reporting errors alongside considerable publication bias. Because corrections for publication bias don’t go far enough, the end result was almost certainly a null one. Consistent with this proposition, a later study that was practically as large as the whole literature covered in that meta-analysis ended up finding a null.

This does not mean that there are not potential gains to psychological well-being in heavily impoverished environments or for specific persons, but it does credibly limit inferences that can be made about the average treatment effect in developed countries.

This is an absolutely superb article for anyone who is interested in interpreting the scientific literature. I have been aware of most this kind of thing on an intuitive level, and obviously spend a lot of time wrangling with issues like fraud in my review of alcohol https://thingstoread.substack.com/p/is-alcohol-good-for-us and even more in my review of parapsychology https://thingstoread.substack.com/p/the-rising-star-of-parapsychology . My very favorite way to go is to investigate things personally and on my own, but I only have so much time and money for that, and it still leaves everyone else to wonder whether I'm falsifying my data or shopping around for effects like everyone else.

Ultimately reading your essay here, it looks like the thing to do is generally to accept evidence in an ascending hierarchy of credibility: no studies < small studies < large studies < meta-analyses < strong studies. Identifying the strong studies unfortunately may require a bit of savvy, and trying to convince clueless people of what you're doing won't always work. What you really, really want is a massive, meticulously designed, preregistered study - and even then, good luck that the people who carried it out were honest. It's quite a tragedy the way politicization and declining levels of trust in the developed world are leaving people without the time and talent for this sort of thing with fewer and fewer credible sources to rely upon in figuring out what to believe.