Fertility Goes Up When Men Win

Successful fertility policy might need to raise male incomes specifically

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

Did you know that many Israelis received reparations for the Holocaust?

The first agreement to pay Holocaust reparations was signed in 1952 between Israel and West Germany. The terms of the deal were that the latter agreed to help resettle Holocaust survivors to Israel. In 1953, West Germany began providing individual payments to some survivors, but eligibility for the payments was limited to only a small number of those affected. In 1956, many more Jews became eligible for payments and immediately received a lump-sum equal to 100% of Israel’s GDP per capita, followed by a monthly stipend equal to 30% of average wages. In 1957, eligibility expanded once again, and take-up became widespread, with recipients set to receive 25% of the GDP per capita and a monthly stipend equal to 12% of average wages. Then, in the 1990s and 2000s, eligibility expanded once again.

Hazan and Tsur leveraged Israeli data on those who became eligible in the 1950s compared to those who became eligible long after their reproductive years (in the 1990s and later) in order to understand the effects of subsidies on the birth rate. We know subsidies work to boost the birth rate—that much is not in question. What makes this study interesting is that it provides an answer to a different question: How should we set up fertility benefits for maximum effectiveness?

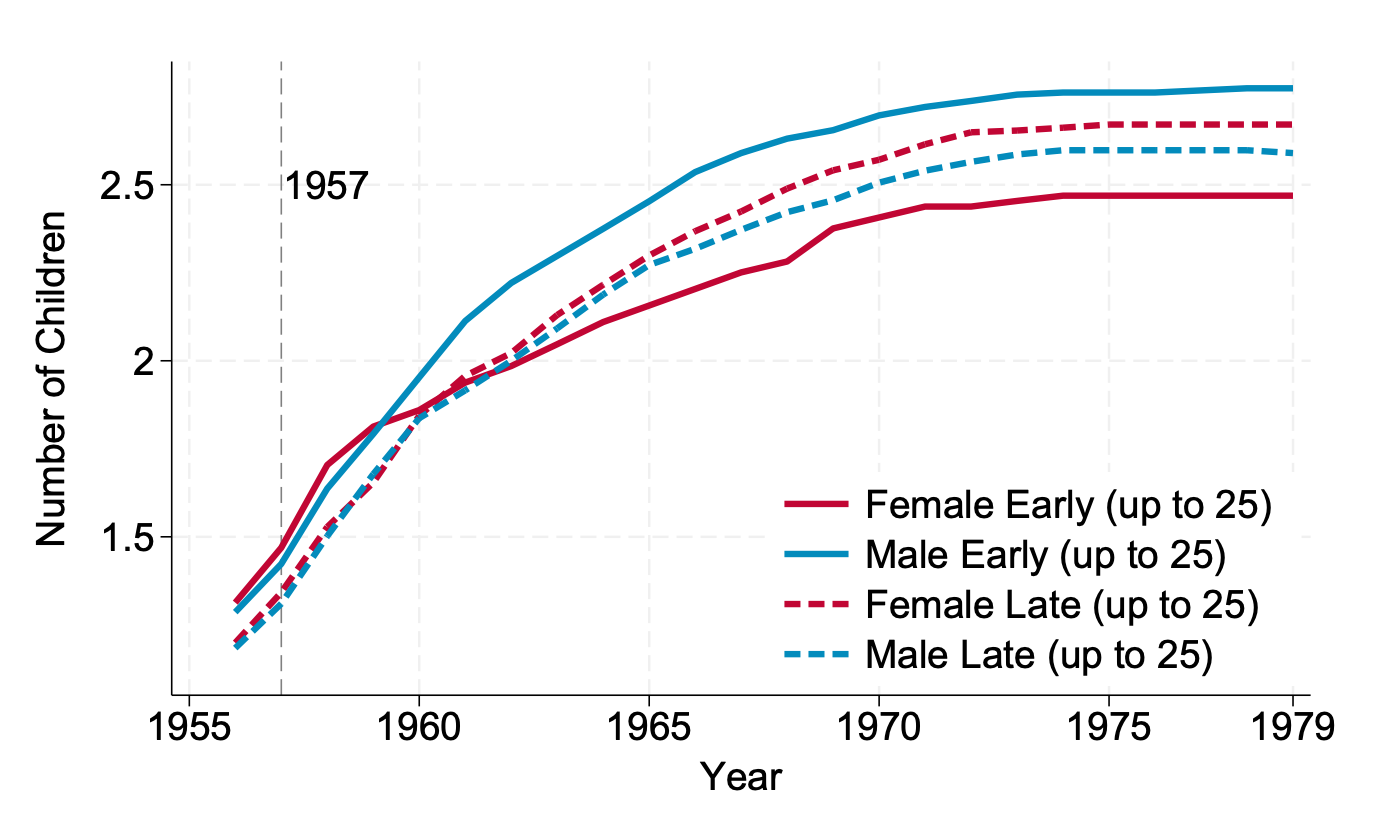

Take a look at this graph from the paper, which is stratified by the sex of the household’s reparations recipient, and see if you can tell what the answer is.

In households where the male partner received the reparations, fertility was a bit higher. In households where the female partner received the reparations, fertility ended up lower. Per the authors:

By comparing fertility outcomes by timing of receipt, recipient gender, and age, we show that young women who received reparations early had significantly lower fertility than comparable households in which the male received reparations. The effect—emerging after 1957 and persisting through the end of the reproductive years—amounts to a reduction of 0.25–0.4 children…

[W]hen women’s individually controlled resources rise, completed fertility falls. This creates a potential policy tension with per-adult UBI. Unconditional transfers that raise individually controlled resources may dampen the effectiveness of pronatalist, child-contingent programmes that lower the marginal cost of an additional birth.

These findings don’t seem to be driven by women changing their labor supply, but instead, through the simple mechanism of greater female bargaining power. That is, when women’s resource control increases relative to men’s, their relationships change in a way that hurts fertility prospects.

This finding is a replication; it’s far from the first time this pattern has shown up.

Among lottery winners, the fertility of men tends to increase, while the fertility of women seems to be unaffected. This appears to be marriage-mediated, as male winners end up with higher rates of marriage and lower rates of divorce—both things that facilitate fertility—and women end up with higher rates of divorce and no change in the incidence of marriage.

The Appalachian coal boom also increased fertility. What makes this such an interesting scenario is that the coal boom was basically purely beneficial for the status of men, as it increased their general employability, their wages, and their bargaining power relative to women. As a result, when the coal boom set in, fertility rose, and when the bust set in, fertility fell, as household incomes fell absolutely, and men’s fell relative to women’s.

Natural resource shocks like the one in Appalachia have actually furnished many examples of male-biased fertility benefits. For example, oil shocks—which primarily boost male career prospects—have been found to boost fertility in Indonesia as well as with America’s fracking boom.

One of the most interesting studies in this area leveraged variation in immigrant numbers to identify the effects of sex ratios on these sorts of outcomes. With data from the 1910, 1920, and 1940 Census samples in hand, it was found that relatively more men from a given immigrant group in an area led the group’s members to marry more, for the women to work less, and to higher male and total couple income:

The… results for men are consistent with the view that higher sex ratios cause men to marry sooner and to try to become more attractive to potential mates… A number of specification checks support the notion that the primary factor mediating these links was increased female bargaining power in the marriage market.

This result may seem different from the expectations you’d get via modern studies, but it makes sense for its era, when women had not really begun entering the workforce en masse yet. But it’s just a digression here; it’s not really on-topic when the topic is male-biased fertility benefits working better than balanced or female-biased ones, it’s just something to think about.

Moving away from causal studies, cross-sectional results generally also support the same pattern regarding bargaining power. In the U.S., for example, the more husbands earn, the more likely they are to have children, whereas the more their wife earns, the less likely kids are. By contrast, in contemporary Sweden, there’s a positive income-fertility gradient for both men and women, but the gradient is stronger and more monotone for men, and it’s more sensitive to timing and parity for women.

With all this information, an obvious solution for fertility policy is to explicitly inject a bias towards men. This may be obvious, but it is a political non-starter. It’s simply not possible policy because it is unacceptable, and it’s not clear how it could be implemented in a way that even had any facial, let alone real, fairness. No one credible would stand for this. We have to consider this ‘obvious’ option off the table.