Yes, Affirmative Action Justifies Discrimination

People who benefit from affirmative action tend to be less qualified

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

It’s taboo to say it, but affirmative action beneficiaries tend to be less qualified than the people who got somewhere on their own merits. That is just a fact, and it can be easily explained statistically.1

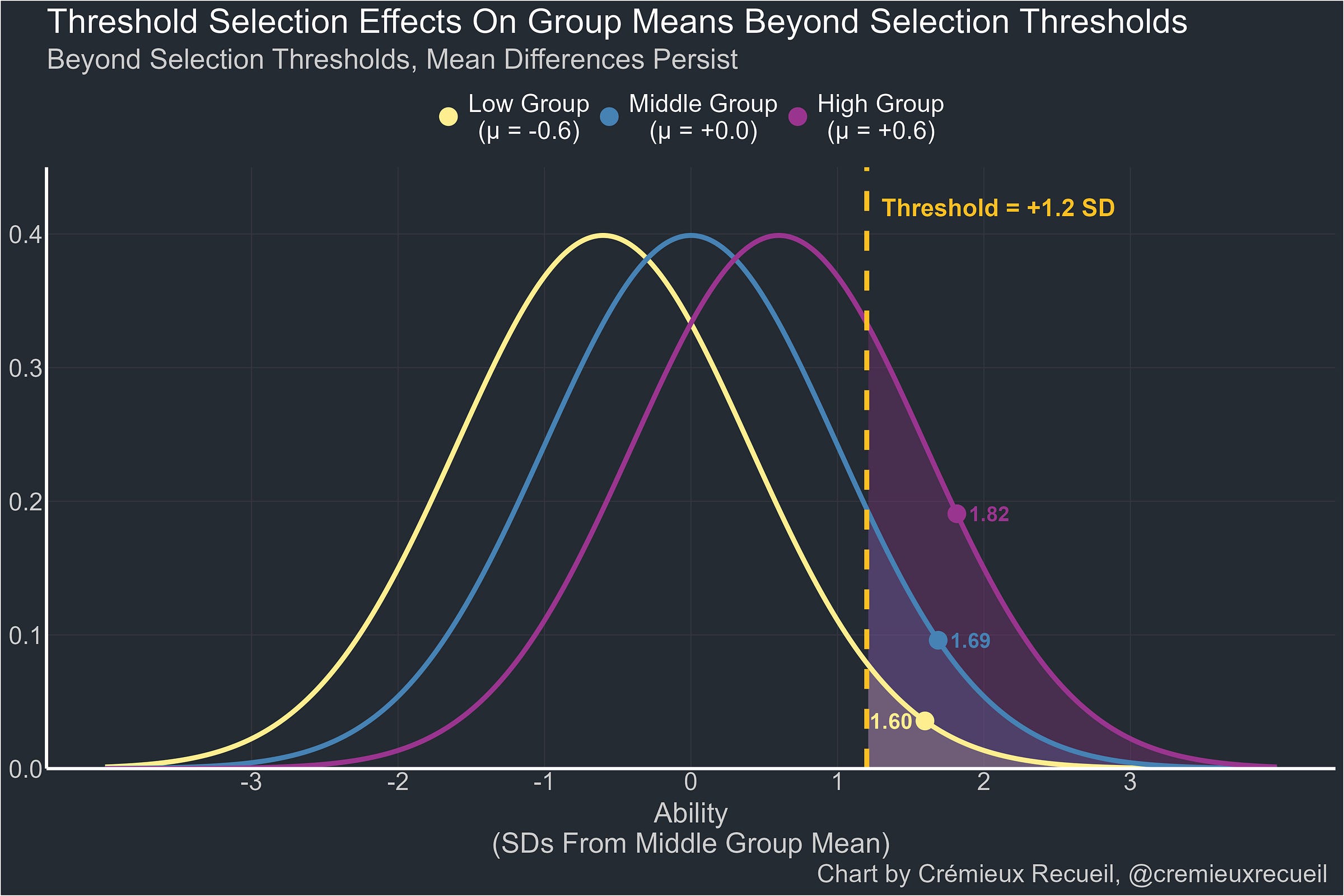

Consider three groups with normally distributed ability with equal variance, who only differ in mean ability level by 0.6 standard deviations on either side of the middling group. Members of these groups will be “selected” if their ability level is 1.2 standard deviations above the mean of the middling group. The means for the groups above this ability threshold are shown with dots on the lines in this diagram:

Selection reduced the initial 0.6 and 1.2 standard deviation gaps, at least among the selected, but it did not eliminate them. Beyond the selection threshold, there is still a gap, and it favors higher-scoring groups. Another notable effect of selection based on this threshold is that just 3.6% of the low-performing group made it past selection, compared to 11.5% for the middling group and 27.4% for the high-performing group.

These results are a mixture of happy and sad. On the one hand, selection has made it so that the ability signal associated with group membership is minimized, and therefore, people selecting from among members of the selected population have little to gain by discriminating on the basis of group membership. On the other hand, selection on such a high threshold eliminates representation for members of low-performing groups.2

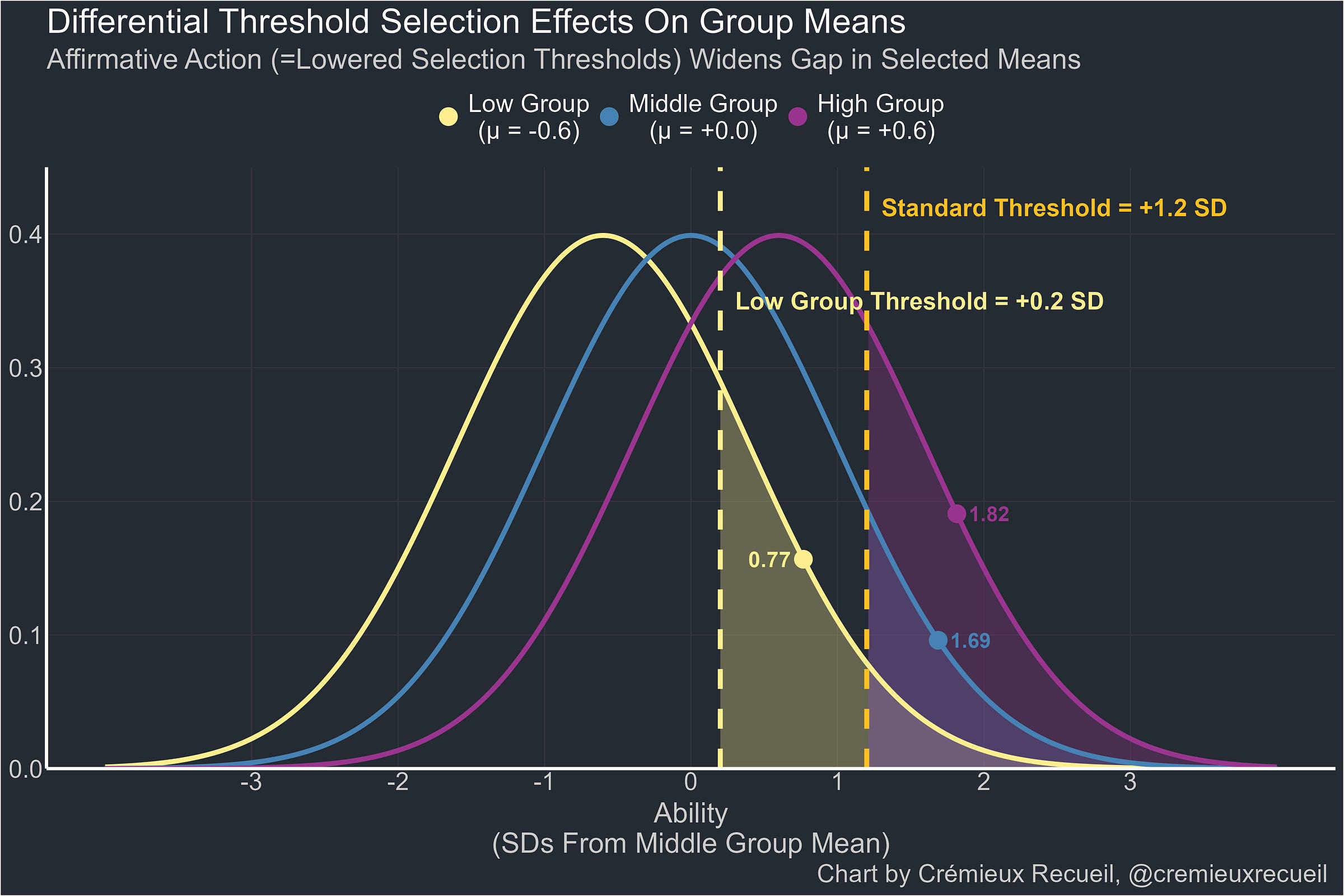

What happens if we try to eliminate the representation gap for the low-performing group by, say, moving the threshold down—just for them!—to about 0.2 SDs above the overall mean? That would come with downsides. See if you notice them:

With affirmative action—a lower selection threshold—in place, there’s now a much larger performance gap between the higher-performing groups and the lower-performing one. This gap is so large that in some domains, it becomes rational to discriminate against selected members of the low-performing group. If you don’t discriminate, you can expect to work with, say, lawyers who are more likely to get complaints made against them, be put on probation, or to be disbarred, or doctors who perform similarly poorly. Why risk that for yourself? Why risk it for your kids?

In short, affirmative action3 makes it rational to discriminate. If there’s affirmative action on the basis of sex, it’s rational to discriminate against professionals from the preferred sex; if there’s affirmative action on the basis of race, it’s rational to discriminate against professionals from the the preferred race or races. Affirmative action makes the credentials of groups benefitting from it worth substantially less than the same credentials for members of groups who don’t benefit from it.

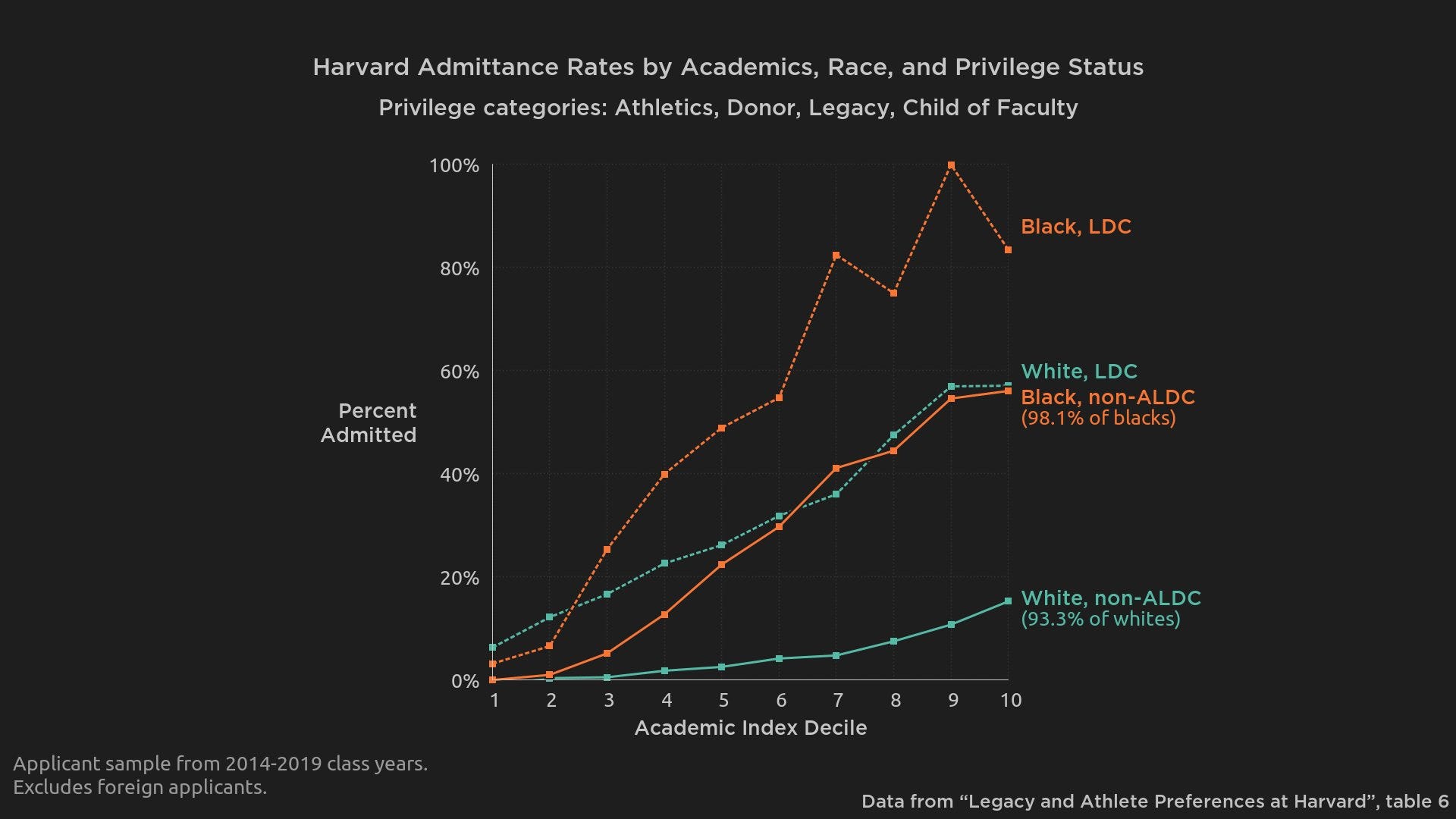

In the real world, this means that racial discrimination against Black professionals is justifiable if you want to receive the highest quality care in settings impacted by affirmative action. Leveraging data from the SFFA v. Harvard case, we can see how this turns out: at each level of academic qualification, Black students were substantially more likely to be admitted compared to Whites. Couple this with the fact that almost everyone who’s admitted eventually graduates from Harvard, and you wind up with a large affirmative action-driven racial performance gap among graduates. Thanks to the wonders of courtroom disclosure, we know that the gap in qualifications at Harvard is actually considerably larger than what I simulated above. Thanks to admissions data exfiltrated from Columbia and NYU, as well as a court case against the U.S. Naval Academy, and comparisons with other universities like the Ivy-11 or just Yale, we know this holds in many other places too.

Given the extreme nature of this racial discrimination in favor of Blacks, it’s no wonder people like Justice Clarence Thomas feel that affirmative action devalued their educational achievements. Luckily, Justice Thomas has a lifetime of work to show that his degree wasn’t an affirmative action get. But other Black professionals may not be so lucky. Until proven otherwise, affirmative action has made it so that the degrees they hold should—from a rational Bayesian perspective—be viewed with suspicion. Thanks to affirmative action, there’s just no way that the average Black Harvard degree recipient can be as capable as the typical White or Asian one.

Who should be the most upset by these facts?

Is it Black professionals, because even if they’re qualified, they’ll need to do more to signal that to everyone? Or is it the wider world, because the quality of the expertise signals they’re offered have been muddled by racially discriminatory policies?4

I think the answer must be the latter group. The former still benefits from affirmative action because there are significant premiums to obtaining a degree that’s more elite than the ones they would otherwise have been able to earn. Moreover, they gain access to higher-quality peer networks via attending relatively elite institutions, and the latter group actually misses out on opportunities because they’re displaced from rightfully-earned positions because admissions are relatively zero-sum. Society as a whole should be upset by affirmative action for the additional reason that it makes credentialism worse, and because it means talent is misallocated on the basis of misleading credentials—a problem made all the worse by the civil rights law-driven support for using credentials instead of just testing people.

What would it take for affirmative action to not matter? There are a lot of possibilities!

One way affirmative action wouldn’t matter would be if ability measurements didn’t predict anything. This simply isn’t the case, so we can ignore this possibility.

Another way affirmative action wouldn’t matter would be if it actually corrected an unjust representation issue. That is, if, in the absence of affirmative action, groups were being unfairly penalized at any given level of ability and affirmative action merely fixed that. But we know from all existing data, from the MCAT, to the LSAT, to the data from SFFA v. Harvard, to so much data contained in IPEDS, that this is not the case, so we can ignore this possibility too.

Another way affirmative action might not matter would be if there are compensating benefits to diversifying elite positions, since credentials can help to put people in those positions, either because they act as a qualification or because they’re required for them. I’ll cite an example of each.

A great many professional organizations and companies thought affirmative action in medicine was justified because of a paper that alleged to show that doctor-patient race matching helped to improve Black infant mortality rates. The paper turned out to have been analyzed inappropriately and, indeed, presented fraudulently. The result did not hold up and it has since then not held up.

McKinsey produced a famous report that linked corporate board racial diversity to firm performance. The report suggested that firms would benefit from racially diversifying their boards, and firms actually acted on this ‘knowledge’ even though the analysis wasn’t a causally informative one. The findings of the report also didn’t even hold up! In fact, nothing of the sort has held up. The best evidence we have for benefits of diversity itself has to do with scenarios with unrealistic characteristics—and thus little reason to think the findings from them generalize—and analyses that are better described as salami slicing adventures.

There are certainly more arguments for (and against!) affirmative action5, but I think they’re all weak for a simple reason. Even if affirmative action could be justified in any number of ways, I’d argue that we still shouldn’t want it on a moral level. Affirmative action is a form of racial discrimination, and it makes it rational to racially discriminate much more broadly. Like most people, that leaves me inherently opposed.

There’s no good reason to think this actually matters, but people still stubbornly feel like representation matters even when they can’t justify that position. What makes representation gaps “sad” is that they run against our typical moral sentiments. They’re obviously not sad to everyone.

Typical affirmative action, that is (i.e., affirmative action favoring lower-performing groups).

Affirmative action comes in many forms. If you haven’t been exposed to the litany of DEI programs directly, consider yourself lucky!

One of these is that affirmative action is a still-necessary corrective for past injustices. This is absurd for many reasons. One is that the way it’s applied is completely uncalibrated for adequately correcting anything. And if it’s applied as a corrective, when is it no longer needed? If the answer is ‘when full equality is achieved’, then it has to be abused, since group ability distributions differ. Another is that it’s not necessary, since there are not deltas in socioeconomic status attainment beyond those predicted by racial differences in ability levels. This finding coexists with the acknowledgement that there’s still racial discrimination in the labor market.

> the latter group actually misses out on opportunities because they’re displaced from rightfully-earned positions because admissions are relatively zero-sum.

Furthermore, this zero-sum dynamic makes affirmative action even worse than the statistical illustration in the first half of your post. There you merely lowered the acceptance threshold for the preferred group, but the zero-sum constraint entails additionally _raising_ the threshold for the non-preferred groups, inducing an even greater difference between group distributions amongst those selected.

The worst part of affirmative action is it's a double hit on whatever group gets the DEI person: the DEI person has to have a minder who might have be doing useful things. The group is really down two peop.le