Missing Fixed Effects Don't Justify Segregation

Ketanji Brown Jackson was too hasty when she extolled the benefits of medical segregation

Beyond campus, the diversity that UNC pursues for the betterment of its students and society is not a trendy slogan. It saves lives. For marginalized communities in North Carolina, it is critically important that UNC and other area institutions produce highly educated professionals of color. Research shows that Black physicians are more likely to accurately assess Black patients’ pain tolerance and treat them accordingly. For high-risk Black newborns, having a Black physician more than doubles the likelihood that the baby will live, and not die.

Those words are from Ketanji Brown Jackson’s dissent in the case of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard.1 The emphasis is mine.

Justice Jackson has made several statements like those, suggesting, in effect, that we need to racially segregate America. Blacks need Black doctors, Blacks need separate services provided by Blacks, and without racial discrimination in the college and university admissions process, there won’t be enough Blacks in professional roles to satisfy the need to segregate.

But—as one might infer from Justice Jackson’s writings generally—her supposition in favor of segregation was poorly reasoned.

Justice Jackson’s belief that the survival of high-risk Black newborns is doubled with a Black physician is based on a misreading of a 2020 study from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study used data on Floridian births between 1992 and 2015 and found that 99.1% of Black newborns with a White physician survived, compared to 99.6% of those with a Black physician.2 The survival rates were >99% for both groups, so it isn’t possible for Black physicians to have doubled survival rates in general, let alone for the “high-risk” Black newborns whom the paper never mentioned.

The scale of the effect of Black doctors on the survival of Black newborns was minuscule, amounting to under a dozen lives saved each year. Regardless, if the effect were real, it would have been correct for Justice Jackson to have said “having a Black physician halves the odds that a Black newborn dies.”

Even though the paper did appear to support that conclusion, it wasn’t strongly justified.

One of the issues in the paper was the choice of estimator. The paper’s headline results were based on ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions, which will work fine with the sorts of binary death data the authors used, but we don’t want ‘fine’ when the topic is this serious and relevant for policy. A logistic model is in general superior for this sort of analysis of rare, binary events3, and the paper’s authors even seemed to recognize that. Presumably because of model fitting difficulties, all the controls the authors were able to use with their OLS models weren’t available when they went to fit their logistic model, so the results of fitting it presented in Table S9 are somewhat more limited than we might like. Nevertheless, that table showed that with a more appropriate model, the effect of physician-patient racial concordance for Black patients was still significant and sizable (logit = -0.440), but it also showed that Black physicians came with increased risk of child mortality (0.157). If we interpret one of these coefficients, why not both?

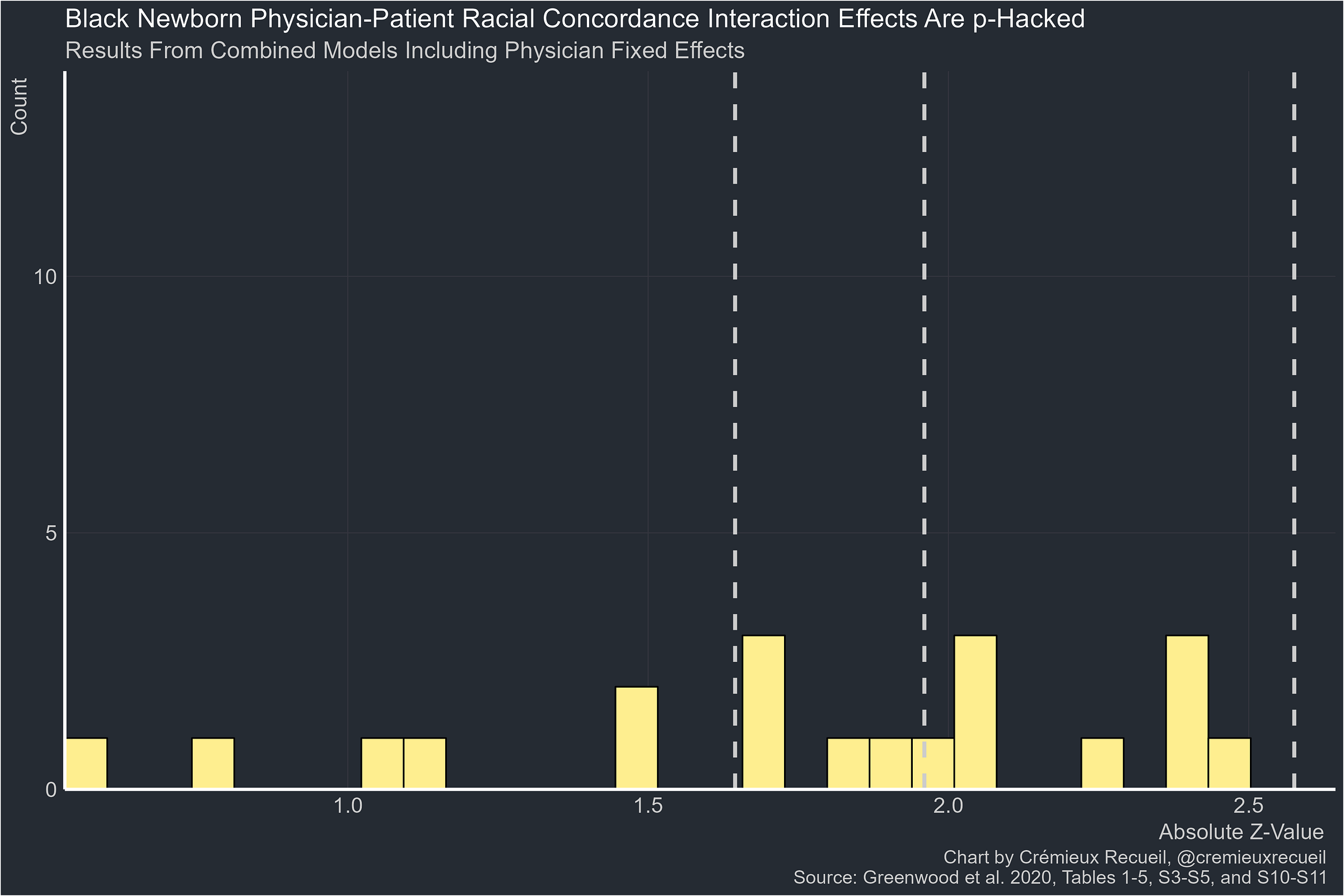

Another issue with the study is p-hacking. Some of the paper’s results are not significant, but of their significant results for newborn survival with all their fixed effects taken out, all of them are between 0.10 and 0.01. I’ve elaborated elsewhere how this pattern indicates p-hacking.

The odds of this happening by chance with a real effect4 are extraordinarily low, so the paper is immediately untrustworthy. But if we believe it, we’ll have to also deal with the fact that the effect is not robust across specifications where we have no a priori reason to think it wouldn’t hold up.

The estimates are all of similar magnitudes so they’re not inconsistent with one another per se, but they are also all marginal, so they are hardly consistent with any effect at all. Even if these were robust, however, we have no reason to think any of them is causal because the authors only had a handful of fixed effects, and among that handful, they were missing the most critical one for causal inference: patient fixed effects.

The authors controlled for patients’ insurance, comorbidities, time of birth, hospital, hospital-year, and physician fixed effects, but even with all of those things held constant, there are many theories that could explain the result that patient-physician racial concordance is related to lower newborn mortality rates. For example, wealthier, healthier Black mothers might pick a doctor of their own race.

To interpret the study’s estimate causally, we need to observe the same patients giving multiple births,5 with some of those patients giving birth with the help of doctors of different races. If the effect holds up after using this fixed effect, it should be causal. The alternative is to watch the same person being born multiple times to doctors of different races, but that design suffers from logistical difficulties.6

Missing Fixed Effects As A General Problem

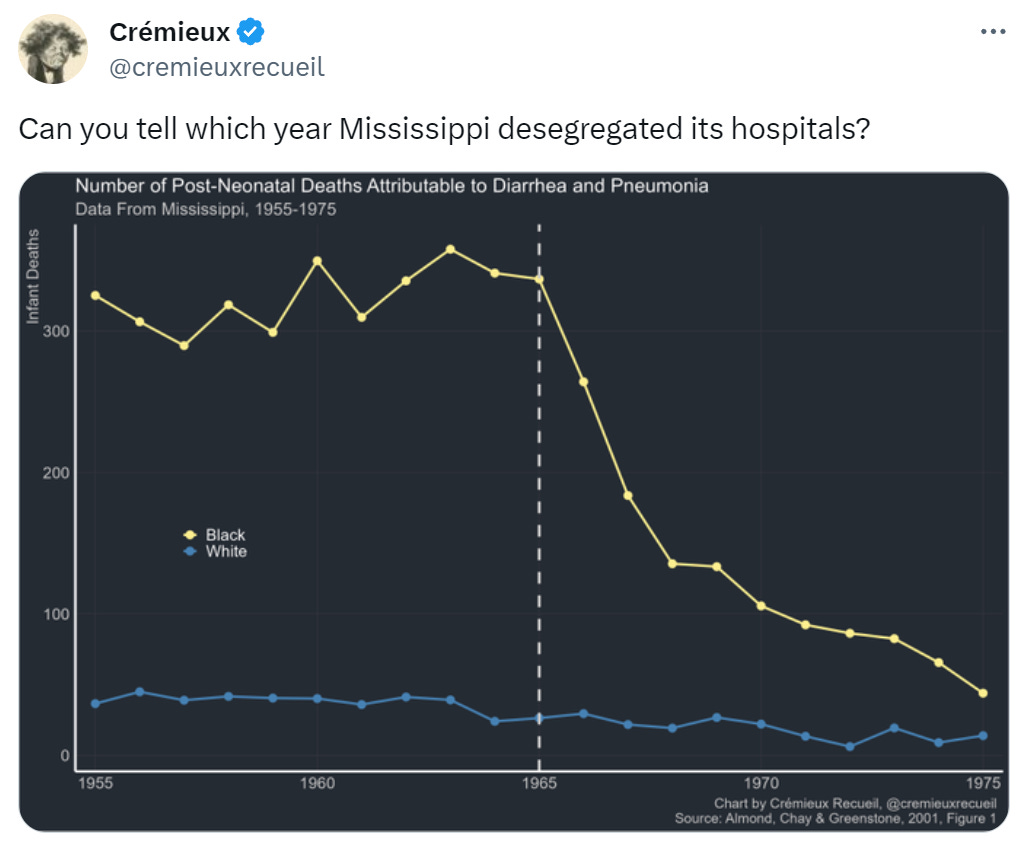

Can you tell?

This post I made back in September shows a plot of data from Almond, Chay and Greenstone’s paper on hospital desegregation in Mississippi. It clearly suggests that Mississippi desegregated in 1965 and that immediately had major, beneficial effects on the survival of Black newborns. The effect was so large that the study’s authors argued that Title VI led to no fewer than 25,000 Black infants being saved between 1965 and 2002.

Their explanation was plausible and the effect was large. The belief in this effect has been popular among economists because it’s believable that desegregation might save lives through channels like giving Blacks access to hitherto inaccessible medical treatment, causing Black and White infant mortality rates to converge like they did. Almond, Chay & Greenstone’s effect was so large that it could explain all of the Black-White infant mortality rate convergence between 1965 and 1971. As the chart shows, that was a period of particularly marked convergence.

But what if the apparent effect of desegregation was an artefact of excluding the right fixed effects?

Almond, Chay and Greenstone computed event-study estimates of the effect of a county gaining a Medicare-eligible hospital. For a hospital to be Medicare-eligible, it had to be desegregated, making this is an intuitively appealing instrument.7 The effect of desegregation measured with this instrument was apparent with a number of county-level controls, county fixed effects, and county-specific linear trends, but because all but five counties in Mississippi had a Medicare-eligible hospital by 1969,8 there was too little variation in Medicare certification dates to include year fixed effects. Accordingly, the effect of desegregation couldn’t be differentiated from any other changes that happened after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

The decline in Black fertility, Black economic and educational progress, the rollout of community health centers, Medicaid—without year fixed effects, in Almond, Chay and Greenstone’s paper, that’s all conflated with desegregation!

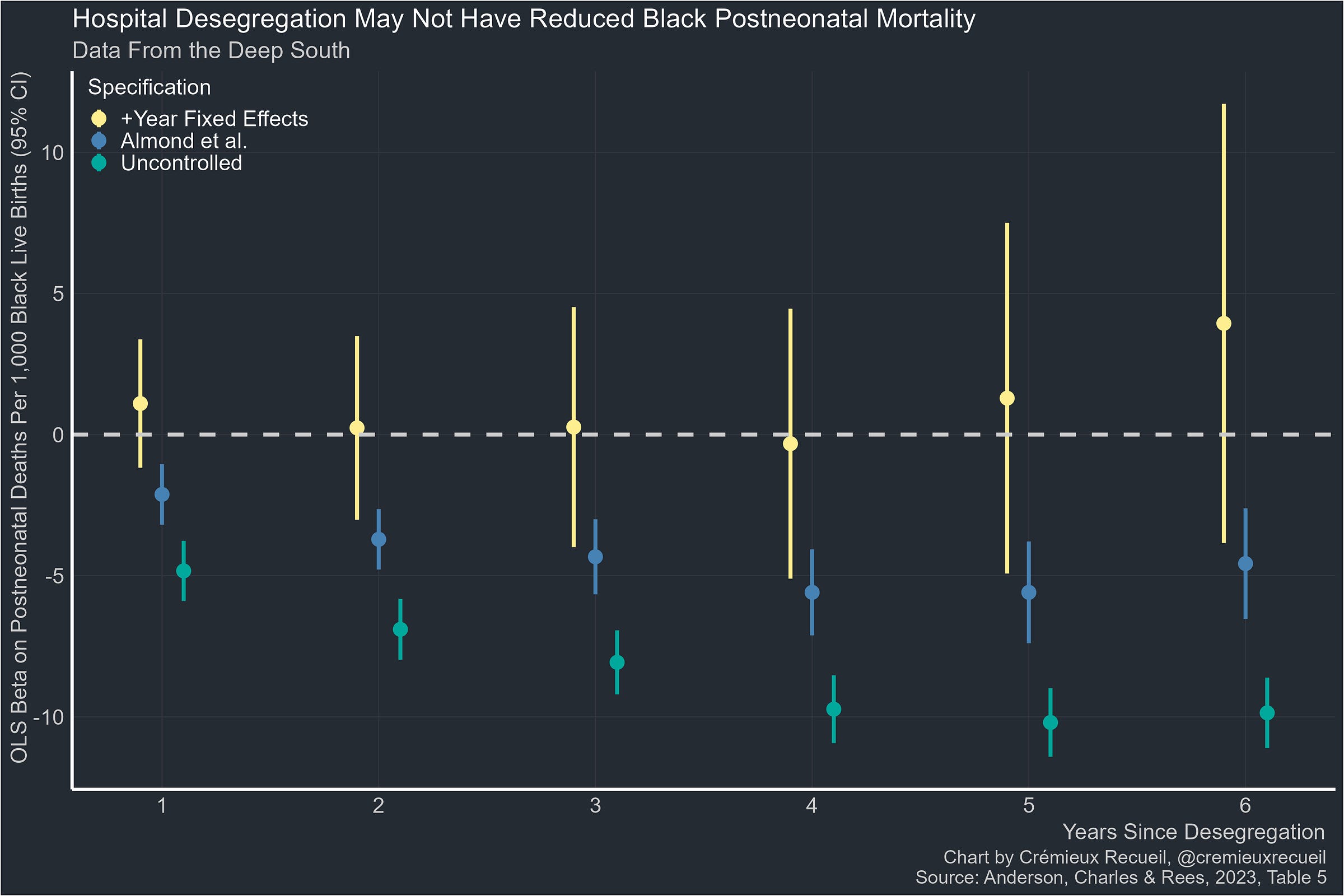

Years later, Anderson, Charles and Rees sought to replicate Almond, Chay and Greenstone’s results, but they used data from five states in the Deep South instead of just Mississippi. Their expanded dataset had more variance in Medicare certification dates, so they were able to estimate year fixed effects.

So let’s compare the uncontrolled event-study estimates of the effect of desegregation on Black postneonatal mortality with Almond, Chay and Greenstone’s maximally-specified event-study estimates and Anderson, Charles and Rees’ version with added year fixed effects:

This is a stunning lack of effect. Apparently the reason for the association of desegregation with improved Black postneonatal mortality was because of improvements that accompanied desegregation, but not desegregation itself.

Since the shocking estimate I posted on Twitter was for diarrhea and pneumonia, we’re lucky that Anderson, Charles and Rees also provided estimates for pneumonia, influenza, and diarrhea induced deaths specifically:

It’s marginal, but apparently, if anything, hospital desegregation might have increased Black postneonatal mortality from pneumonia, influenza, and diarrhea.

How Often Is This a Problem?

In the two examples I’ve cited so far, failure to include the right fixed effects either precluded causal inference or completely nullified—and potentially reversed—results.

There’s no telling how often this happens. When it came to physician-patient racial concordance effects on infant survival, the problem was obvious; for hospital desegregation, the nature of the problem obviously wasn’t as clear. Neither of these is a one-off.

Some people hold the reasonable view that when teachers partake in professional development programs, they become better teachers, resulting in benefits to their students. In line with this view, cursory investigation suggests that is the case. But when student fixed effects are thrown in, that conclusion suffers an about face and the effect is either nullified or teacher professional development becomes harmful to students’ achievement test scores.9

In a paper published in mid-2023, McNeil, Luca and Lee used the British Household Panel Survey to provide convincing evidence that being born into a location with high unemployment had major, long-term impacts on individuals, making them more likely to support government intervention in the labor market, “less progressive on gender issues, and less likely to support the Conservative Party.” However, this study lacks the required design-based controls to actually render the conclusion its author wanted to in a credible way. The issue is that there’s residual confounding because we cannot observe the people born into places with high unemployment prior to their birth, so sorting-induced confounding remains.10 If there were observations of siblings born in locations with different levels of unemployment, this issue could be resolved because siblings could be compared to see if the effect remained within sibling pairs.

There are innumerably many instances where we can go so far and eliminate so many potential explanations from consideration in a study while the possibility that a crucial fixed effect or other residual issue remains. Cutting out these alternative explanations for findings is hard, and the data to address these issues often isn’t available. McNeil, Luca and Lee probably won’t find a dataset with everything they need for a long time; Almond, Chay and Greenstone didn’t have data beyond Mississippi and it took another group fourteen years to address the issue with their study. How many people were misled over that decade and a half? How many people are still being misled by it?

This issue is important because it impacts policy and research priorities. It’s an issue that will also always be with us in spite of our best efforts. All we can do to combat it in the long run is to cultivate a culture of radical data openness. Many people don’t want that, however, as they fear data will be misused. For better or worse, they tend to be people with views like Justice Jackson’s. Let’s hope their numbers diminish and more reasonable people win the day, or we might end up with more Supreme Court Justices arguing in favor of segregation.

September 2024 Postscript: Mystery Solved

Thanks to a wonderful new reanalysis of Greenwood et al.’s paper on physician-patient racial concordance, we now know why there seems to be a benefit to concordance for Blacks.

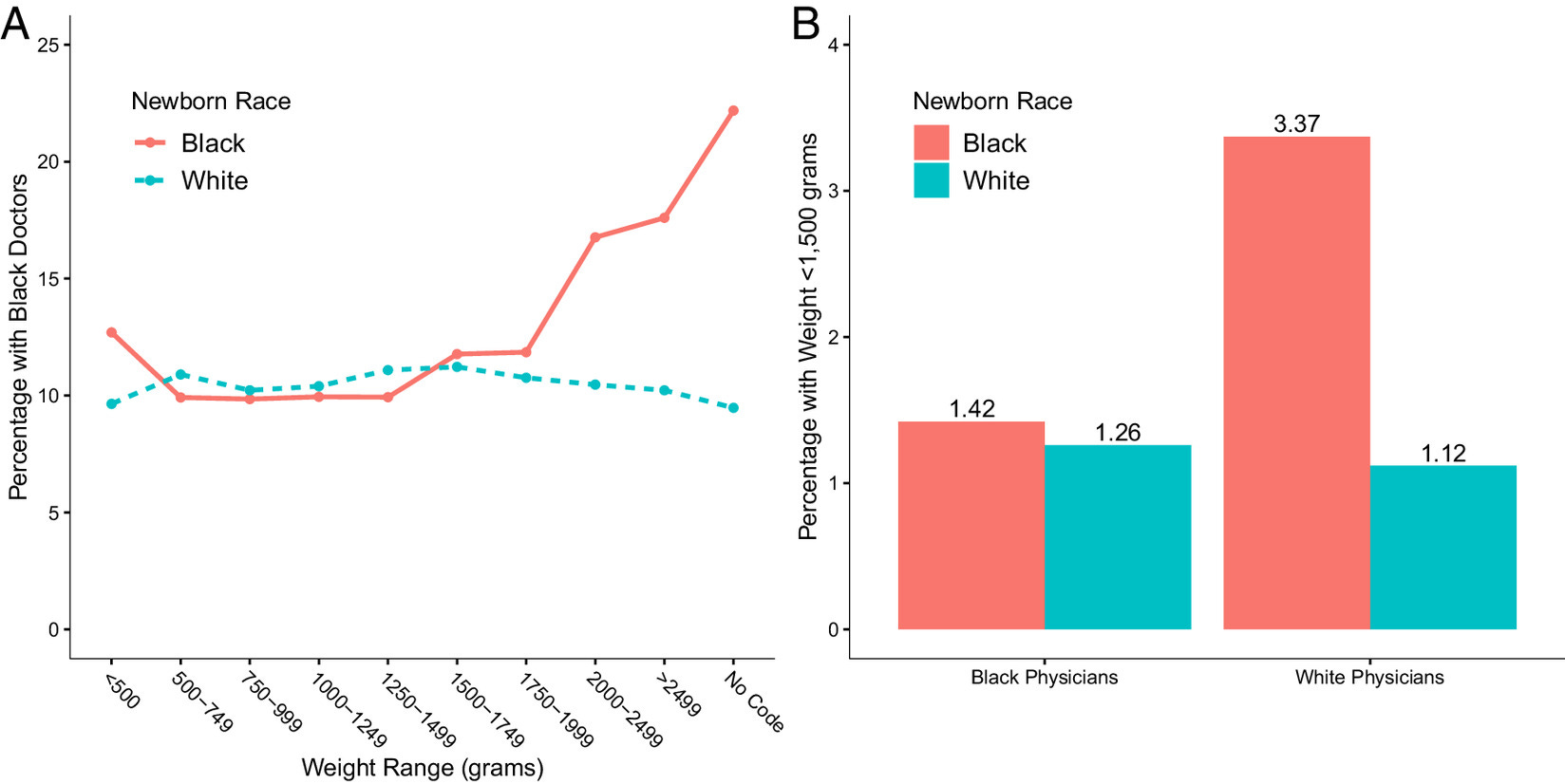

The first thing to note is that low birthweight is a predictor of mortality, and though the overall infant mortality rate for the U.S. is low, the mortality rates for extremely small infants are very high. Extremely small babies have very high mortality rates regardless of (A) whether they’re Black or White, or (B) if they’re delivered by a Black or White physician:

The reason this matters is unfortunately simple and it indicts the publication process at the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: the original analysis that showed benefits to patient-physician racial concordance failed to control for birthweight. Among their long list of controls and their numerous fixed effects, they were missing one that should be incredibly obvious, but apparently wasn’t. And that matters because (A) Black babies with high birthweights—and thus lower mortality risk—disproportionately went to Black doctors, and (B) Black babies with low birthweights (<1,500 grams) disproportionately went to White doctors.

When you account for this fact through simply controlling for birthweight, the positive impact of having a Black doctor dissipates to nothingness:

If you wanted to put this in practical terms, then in the original model, the mortality rate for Blacks was -0.49 percentage points (pp) lower with racial concordance and the effect dropped to -0.13 pp with the full suite of controls. This means that, since newborn mortality was 0.8 pp lower for Blacks than for Whites, concordance reduced the gap by about a sixth (0.13/0.8, p = 0.009). In the final specification from the best-fitting model with birthweight controlled, the effect of having a Black doctor on the mortality risk for Black infants is, instead, nonsignificantly reduced by about 1.8% (0.014/0.8, p = 0.681).

Why does this indict PNAS? Simple: Because they should have demanded transparency. There was no way to know that birthweight differences drove the wildly popular results they allowed to be published in their venue, but it should have been an obvious question for anyone interested in this topic to ask and the answer should have been discoverable by looking at the model specification that PNAS didn’t require to be published. There is simply no way around this: It’s known that Blacks have lower average birthweights, and it’s likely that harder cases (i.e., those with lower birthweight) are assigned to more skilled physicians, and that those will tend to be White, leading to an apparent physician-patient racial concordance boost for Black physicians in the absence of appropriate fixed effects or, as we’ve seen here, a control for birthweight. It’s also clear that the authors of the original analysis knew they should have controlled for birthweight. Their only mention of it was this:

Black newborns experience an additional 187 fatalities per 100,000 births due to low birth weight in general.

And yet, their analysis lacked the decisive control, so they ended up providing a Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court with part of her justification for racial discrimination.

March 2025 Postscript: The Original Authors Are Frauds

Do No Harm—a nonprofit committed to fighting identity politics in medicine—recently partook in a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request that dredged up emails and an early draft of the Greenwood et al. paper alleging Black newborns benefitted from the experience of a Black doctor. What they found in those emails indicts both the authors and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: they found fraud.

The FOIA’d documentation can be found here. What it reveals is incredible.

Firstly, the authors knew they should not have been making causal claims. The documentation reveals that a reviewer notified the authors of the need for patient fixed effects—the fixed effects I discussed above. They were aware of this, could not do it because they lacked patient identifiers—something we should have known given the importance of this particular fixed effect—and simply did not explain it, before lapsing into using excessive causal language.

When you cannot perform an analysis due to a data limitation, you do not simply act as if there’s not a problem, but that is exactly what they did.

Secondly, we now know that the authors had absolutely no excuse for ignoring the role of birthweight, since a health economist they consulted asked them about it. The authors even recognized that using birthweight might be important for interpreting their results in light of potential selection, based on their consultation with that economist. It was already clear that they understood the key role of birthweight, but this makes that even more apparent.

And finally, the fraud. In the original paper, there’s a quote:

Concordance appears to bring little benefit for White newborns but more than halves the penalty experienced by Black newborns. [Emphasis mine.]11

Now that we have access to an earlier draft of the paper, we see that it contains the following line:

In this model, white newborns’ [sic] experience 80 deaths per 100,000 births more with a black physician than with a white physician, implying a 22% fatality reduction from racial concordance.

Apparently, this statistically significant 22% reduction was “little benefit”, and not worth mentioning. Who knows if it would survive a control for birthweight12, but the point is that this is equally important to the results they did choose to show. They found this, and they chose not only to not show it, but to omit it and lie about what they found, claiming that racial concordance was only a benefit to Black children, when their method showed it helped White children, too.13

Why did the authors do this? To quote:

I’d rather not focus on this. If we’re telling the story from the perspective of saving black infants this undermines the narrative.

This undermines the narrative. The important thing to these authors was not doing science, or discovering facts about the world, it was promoting a narrative. As one might expect from narrative promoters (as opposed to real scientists), their narrative came with lying, because their narrative was wrong, and they had the tools and the warnings needed to have figured that out. To make matters worse, either the person who wrote that was wrong, or the person who created the chart PNAS decided to publish (Fig. 1) was. And guess what? The authors were aware of that too. One of them wrote as a comment on the Figure:

Why is the White-Patient Black Phys not significant here but PhysBlack coefficient is significant in Table 1: Column 4?

Whatever the answer that person might have received, I know the real answer: dereliction. The Greenwood et al. paper is an example of narrative-crafting and a total dereliction of the authors’ duty to truth-seeking and doing no harm. Instead, they caused massive harm, they fomented racial antipathy towards Whites, and no doubt endangered the lives of Americans, while certainly altering research trajectories and skewing funding towards dead-end research.

The course of action is simple. Outside of publication, these authors ought to be criminally prosecuted if they fabricated results or, at minimum, booted from academia for negligence and distortion of facts in addition to being barred from accessing the sorts of administrative data used in their paper. The authors are all complicit in harming the American people through intentionally constructing a vile racial blood libel that they carelessly promoted in the press as if they were simply telling hard truths the nation needed to hear. But the nation did not, because there were no hard truths to be found in Greenwood et al.’s paper, only lies. For all of this, PNAS must retract their work.

Note that the effect on mortality risk was specific to pediatricians, not obstetricians.

The paper also suggests that physicians may have trouble learning whatever behaviors give rise to the patient-physician concordance effect because experience with Black newborns is seemingly irrelevant (Table S12).

The comparability of linear model estimates is a point in their favor that has no bearing on anything written here except for the comparison of their magnitudes across specifications.

The odds are less extraordinary in this specific case because the estimates are all based on estimating the same effect in different scenarios. However, the effect is still dubious because it falls into this range.

Other patient characteristics like age at birth will also need to be controlled.

A randomized controlled trial could work, but as I noted here, such a design might be hard to implement in America and even if it’s done, it’s likely to have major generalizability concerns.

Unfortunately, investigating the effects of physician-patient racial concordance in another country doesn’t help, since we are interested in an effect that people will readily argue is culture-specific: specific to African descendants of slaves, specific to doctors who benefitted from affirmative action, etc.

Almond, Chay and Greenstone’s estimate of the effect of desegregation is backed up by more recent findings like that the advent of Medicare-eligible hospital access was associated with greatly reduced non-White elderly pneumonia mortality.

Or their residents had the option of receiving care at a certified hospital in a bordering county.

This is charted here. It is also noted there that this study shows simply using student-level controls is insufficient, as the result was not the inversion observed when student fixed effects were used.

In other locations on Twitter, I have posted about the likely insubstantial and absent effects of teacher-student racial concordance.

Additionally, it was explicitly—and we now seem to know, incorrectly—stated that the White-White concordance effect was null. They wrote:

The Physician Black coefficient implies no significant difference in mortality among White newborns cared for by Black vs. White physicians (columns 1 to 5 of Table 1). In contrast, we observe a robust racial concordance benefit for Black newborns, as captured by the Physician Black * Patient Black interaction.

This seems more plausible than the reverse given known differences in doctor skill by race.

Albeit, again, not in a rigorous, causally-informative way.

I continually (without success) try to understand this pretzel logic that outcomes for minorities in areas of healthcare and educational attainment can somehow be tied to getting treated or taught by fellow minorities. If this were true, the empirical evidence would be clear.

For example, wouldn't Inner-city school testing scores would be some of the highest in the nation?

Vinay Prasad evaluated a similar study claiming that in counties with more black doctors, black patients live longer: https://open.substack.com/pub/sensiblemed/p/does-black-representation-save-lives.