Fertility in an Ideal World

What would society look like if women had as many kids as they wanted?

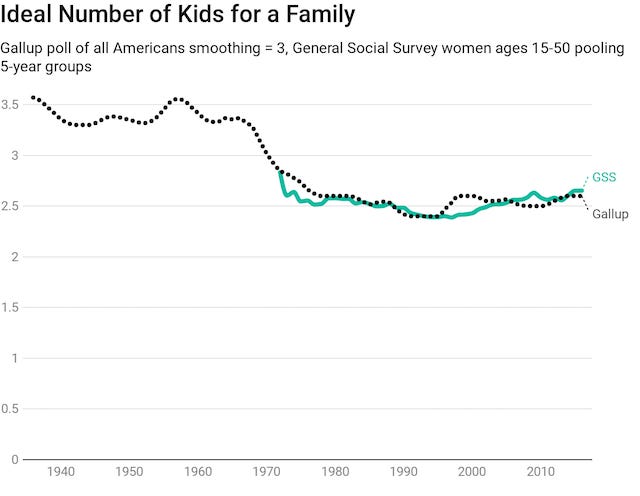

If women only had all the kids they wanted, we wouldn’t have a fertility crisis. That is the conclusion reached by basically anyone that looks. Consider this post from the Institute for Family Studies (IFS). They found that the ideal number of children people reported wanting has consistently been above the replacement rate of 2.1 per woman.

And their conclusions are highly interesting:

The decline in fertility is not due to women wanting fewer kids. It also isn’t due to men wanting fewer kids, or to population aging. Nor is it due to abortion: abortion rates are actually declining. It may be partly due to the rising usage of longer-acting contraception, or diminished sexual frequency, or any number of social factors. It might also be due to economic pinches on household budgets. But the truth is, none of those are probably the biggest driver of declining fertility. The decline in fertility is mostly due to declining marriage.

If the fertility crisis is a product of the unmet desire for children, policy that fills in that gap would be sufficient and it might be popular enough to implement. It could even be sold as a patriotic-moral imperative if we called it The American Family Act or some other standard-waving euphemism.

But this would only deal with the “quantity” part of the birthrate problem. To be sure, the lacking number of kids is discussed far more than the quality of those kids, but the people who have the most kids are the least capable, and when fertility policy is embraced, that doesn’t change.

Consider Sweden. For as long as they’ve recorded, the relationship between fertility and education or, more controversially1, intelligence, has been consistently negative. When Sweden dramatically expanded their family policies, they had some success at not only stabilizing, but momentarily increasing the birth rate. But, the least-educated Swedes still had more kids than their more highly educated peers2, although less so, but some of the apparent reduction in the fertility-education gradient was attributable to changes in the mean level of education.

These fertility-related qualities are important. Intelligence predicts success, not only in terms of income, education, socioeconomic mobility, and occupational prestige, but also in terms of health and sanity. And, there has been some decline, with the effect being largely relegated to intelligence itself rather than specific abilities like the Flynn effect is and, due to Bateman’s Principle, the negativity of the relationship between intelligence and fertility is greater for women than for men.3

If we’re pursuing policy aimed at helping women achieve their ideal fertility, we have to compare a few scenarios: the ideal, the real, and applicable policy options. Ideal fertility is just the case where every woman has the number of kids she personally believes to be ideal; real fertility is the situation on the ground, where we’re working entirely with women’s realized fertility in terms of the numbers of kids they have. But there are a lot of potential policy options, so looking at those first two scenarios should be more feasible because we actually have good data for dealing with them.4

To get a good picture of what real fertility and ideal fertility look like, I'm going to use the General Social Survey (GSS). The GSS has an intelligence measure, the Wordsum vocabulary test. Here’s how its results are distributed for the full sample of women.5

As the IFS showed, participants were asked how many children they considered ideal for a family. They were also asked how many children they currently had. Plotted next to each other, those variable’s relationship is not resoundingly clear.

But plotted differently,6

It seems women anchor to between two and four children as the ideal number, but the actual number of children they have is much less cleanly distributed. If every woman had her desired number of kids, we would have very few women without any children, very few with just one child, lots of families where the parents have replaced themselves, lots of families where they’ve done that and a bit more, and a large number of families where they’ve doubled their size, coupled with a modest number of large families. Clearly the largest impact of achieving ideal fertility would be a huge reduction in childlessness and only-children.

If we take a woman’s ideal number of kids as her desired number regardless of level, we can also estimate what women want relative to what they currently have.7

Given 79% of women don’t want more kids, it might be odd to consider that it is also true that if all women had their ideal number of kids, we wouldn’t have a fertility crisis. But it shouldn’t be: the women who want fewer children don’t want that many fewer, and the women who are alright with their current number usually have some kids. But enough of the women who want more are childless or below their ideal, so the ideal fertility level still exceeds the real one by a considerable and growing margin.

Now let’s combine Wordsum and this fertility information.

There’s quite a bit to say about this. For starters, regardless of cognitive ability, women wanted more kids than the replacement rate and more kids than they actually had. It’s also clear that cognitive ability varies with both realized and ideal family sizes. However, cognitive ability more strongly differentiated realized than ideal fertility.8 The extent of this was enough to clearly show that the only women adequately replacing themselves have below-average intelligence. Because of the stacked natures of these bar plots, it might be clearer to just plot the gap.

And to be even more explicit, the realized fertility gap between the smartest women and each other cognitive class averages 1.85 times the ideal fertility gap. In the real world, the smartest women have 0.83 fewer children than the least intelligent women, but in the ideal world, they only have 0.40 fewer.

So, how dysgenic9 is the real world compared to the ideal one? With a Wordsum mean of 5.986 in the current population, the real world population mean if we simply considered these women’s fertility representative for the next generation would be 5.785. Contrarily, in the ideal world, the mean moves much less, descending from 5.986 to just 5.922. In terms of the standard IQ metric, the real world produces a generational loss10 of 1.455 IQ points versus just 0.462 in an ideal world. A world in which every woman has the number of kids she considers ideal is 3.15 times less dysgenic than the real world.

But the benefits obviously do not stop at reduced IQ loss. As already mentioned, women in the real world have fewer kids than they want. Alongside its smaller level of IQ loss, the ideal world also has a 27% more populous next generation.

With all these facts, we can make a powerful conclusion: women’s ideal fertility is sustainable in terms of numbers of people produced and it is substantially more sustainable in terms of the quality of people produced. If women had all the children they wanted, we would not have to worry about the quantity or quality of the population for generations to come.

The options to actually help people achieve their ideal fertility are limited. It is a political non-starter to restrict women’s education or employment, so a full recovery of pre-demographic transition fertility rates is certainly not on the table. Getting to ideal fertility also requires finding stimuli that do not just boost everyone’s fertility but, instead, selectively boost the fertility of smarter women.

One option to reduce the fertility-intelligence differential is to make IUDs universally available. The lower a person’s intelligence11, the greater their risk of an unwanted child. If every woman had an IUD in, the rate of unwanted childbirth would fall to nearly zero.12 The problem with this is that a considerable but notably declining share of pregnancies in general are unwanted, unplanned, or due to accidents rather than being due to planned or unrestricted procreation in marriage or otherwise. So doing this could crater the fertility rate, exacerbating the quantity problem.

There is an obvious way to boost the population size in general, and it’s immigration. The problem with this is that it is politically contentious, it leads to cultural and political changes that many — and quite likely the majority in most countries — may consider undesirable, and it runs into the quality problem. But a more in-your-face observation about this proposed population replacement-based solution is that one of the few ways immigrants seem to assimilate besides learning the language is by adopting low fertility. Consider the data from Denmark which clearly illustrates immigrant’s convergence to and, perhaps, even falling behind Danish fertility levels.13

Advanced forms of family policy that explicitly target women based on their education level or socioeconomic status are theoretically easy to implement and they could help a bit, so they’re possible, but they have no political viability. They would quickly be denounced as eugenic policies, as regressive, etc. Any family policy that involves subsidies and the like will have to funnel resources up through seemingly more innocuous means like tax breaks. Unfortunately, the magnitude would hardly end up doing enough with realistic policy options.

There are two policy proposals I believe would have some effect. The first is land use reform. There is a literature worth considering that reliably indicates that high housing prices reduce fertility among renters and the young while increasing it among older women and homeowners. The net effect is a reduction in fertility. Consider the following:

Shoag & Russell found that areas with stricter land use regulations had lower fertility rates, and that fertility rates were primarily reduced for teens and young women, while they were raised to a smaller degree in women older than their thirties.

Seah used the Mariel Boatlift to assess the effect of housing prices on fertility, with the logic being that immigrants need places to live and so an immigration shock acts as an instrument for increased competition for a constrained stock of housing. Native fertility declined in aggregate, but the effect was only due to the fertility of renters rather as opposed to homeowners.

Dettling & Kearney found that an increase in housing prices had a negative effect on fertility, but for homeowners, the price effect is positive due to an increase in their home equities. Accordingly, assuming homogenous price changes, the net effect of prices should actually be an increase in American fertility because American homeownership rates are high nationally. But, though not in their paper, it’s clear that pricing is spatially heterogenous in a way that means price increases are a net drain on birth rates.

Clark found that living in an expensive housing market leads to delayed fertility, but in the time period covered by his data, total fertility wasn’t affected.

Washbrook found that housing prices elicited positive, temporary effects on the fertility of homeowners and social renters, but long-lasting, negative effects on family renter fertility, with a more modest negative effect on private renters. For the nulliparous, the effects were more often and severely negative than for people with previous births.

Stone found that higher rents were associated with lower fertility. Additionally, larger and less crowded houses were associated with higher birth rates.

Clark & Ferrer found that housing prices benefitted homeowner but not renter fertility, and these beneficial effects were only found in people who stayed where housing prices were high.

La Cava found evidence that housing capital income has risen due largely to lower interest rate, lower CPI, and new housing supply constraints: “In effect, I argue that the fall in nominal interest rates over the 1980s and 1990s raised the demand for housing and pushed up housing prices and rents (relative to non-housing prices) in supply-constrained areas. I estimate that the long-term decline in interest rates can explain more than half the increase in the share of nominal income spent on housing since the early 1980s.”

Improving housing prices by building more homes should help with fertility. Because many professionals postpone family formation until they’ve made career progress, the inability to move to cities because of high housing prices may have a disproportionately negative effect on relatively intelligent women. In so far as these women are delaying their fertility due to high housing prices, it is certainly the case that they’re having fewer kids than their ideal.

The other proposal I believe would work is to fight the tempo effect (i.e., fertility timing effect) induced by education. This specific tempo effect is something that promotes the negative fertility-intelligence gradient. The way fixing this works is simple: either get kids into school earlier so they get out earlier, or just let them out earlier with the same starting age. If people spend fewer years in school, they have more adult life to live, and in that adult life, they’ll have more time to have kids. An additional appeal is that if this policy is pursued by electing to start earlier while spending the same amount of time in education, more children will have access to early childhood education and they’ll still start adult life a few years younger.

Policymakers could effectively push forward every milestone from high school graduation to college graduation to starting a career, and so on and so forth.14 With another year or two to have kids — years in which the situation would normally discourage people strongly from having kids because they’re in school or they’re starting their job or moving around or whatever else — this would be virtually guaranteed to provide some boost to fertility. In so far as certain milestones are segregated to the highly intelligent, as is the case with acquiring a PhD, the way through which this achieves a reduction in the negative fertility-intelligence gradient is obvious.

People may object to this policy because there are several studies of schooling extensions that seem to find benefits to poverty levels, home values, incomes, etc. But these studies are largely relegated to places with very low levels of initial education, they are severely p-hacked, and they not infrequently suffer from the use of instruments that are correlated with variables that influence the metrics authors choose to test the effects of education. When you have a high-powered test of education expansion near the educational frontier, the result is usually bupkis.

Lutz & Skirbekk explicitly proposed looking at policies aimed at addressing the tempo effect, since they seem to be “powerful and socially acceptable”. They described five scenarios,

A baseline, where the tempo effect is maintained and, because of biological limits on reproduction, the quantum (total fertility) must fall to produce a constant period total fertility rate.

The case where the increase in the mean age at childbearing ends and the period fertility immediately increases to the tempo-adjusted fertility level.

The case of a school reform that has the effect of reducing mean childbearing age by two years.

The case where such a reform leads to a tempo-quantum interaction, yielding higher total fertility.

The case where the increasing postponement of childbearing ends and a school reform also happens.

For Austria, Bavaria, and Italy, the scenarios increasing the fertility rate and promoting earlier childbearing would lead to greater improvements in the old-age dependency ratio, larger populations, and, based on data from outside the paper, likely greater prosperity. For countries suffering primarily from tempo effects like Korea and Japan, the value of these proposals is accordingly amplified.

Thankfully, education does not seem to impact intelligence, so reducing the years spent in education is unlikely to harm population-level cognitive ability. Making our way to the ideal by taking a bite out of education is probably safe, but more options must be considered.

Politically, not scientifically.

And there are nonlinearities that make for reduced fertility among the severely intellectually disabled.

And two more things. First, the typical policy option that promotes fertility will not act with respect to this gradient. Second, it is politically difficult to sell a policy option that is aimed at taking down this gradient.

Most statistics in this article are adjusted for sampling year and age of the participant. Results for fertility do not change much using women with likely completed fertility (i.e., age 45+) compared with age adjustment.

The scale for the ideal number of kids was 1-7 whereas the actual number of kids was on a scale of 1-8+, so for this plot, the right tail of actual kid numbers was Winsorized. Because of the small numbers of such families, this couldn’t make much of a difference.

Obviously the ideal family size can be influenced by things like a woman’s age and fertility status, current number of children, marriage status, quality of partner, and much more. Longitudinal data on women’s preferences for children across the lifespan and in relation to events like births and marriages would help considerably in the effort to understand this construct.

If the GSS used a better test we could probably see even more differentiation. Investigating that will have to wait.

Eugenic fertility means traits or the levels of traits regarded as good are increasing because people with more desirable traits or trait levels are having more kids than those who have less desirable ones. Dysgenic fertility means those traits or trait levels are decreasing for the opposite reason.

Assuming no renorming. This section also uses rounding in text, but calculations were done without it. It is also worth noting that the distribution of the fertility decline with respect to cognitive ability makes this dysgenic pattern worse with time.

Using a prospective subset (i.e., no children and age below 30), the results replicate very closely, with the ideal fertility dysgenic effect being equal to 0.682 IQ points (5.955 to 5.869, SD = 1.892).

Because this prospective cohort has no kids to allow a comparison between their ideal and realized fertility, comparing it to the full sample, the dysgenesis is 47% as large as the realized dysgenesis and the ideal population is 24% larger than the realized one; there is practically no change in this result when the prospective cohort is removed from the full sample and the comparison values are recalculated.

But only to a point: fertility is greatly reduced for the severely mentally retarded.

And this can be marketed as increasing the control women have over their own reproduction, getting them off of medication that affects their emotional lability, preventing reproductive risk from rape, etc.

The heritability of fertility won’t save this, either. Even a group as impressively prodigious as Mormons can’t keep the rates sufficient. The situation in Israel is also interesting. Krugman’s proposed permanent stimulus, while interesting and probably beneficial, will also not fully fix issues related to fertility, as its stability and utility runs against demographic limitations like every policy proposal.

And greatly increasing grade skipping for qualified students would also help, with the added benefit that it would favor increasing the length of reproductive careers by a greater amount for more intelligent people.

So we don’t have a cultural problem. Desires are where they should be. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.

One fundamental fact in the fertility discussion is this: raising children is time-consuming, difficult, and expensive. If people generally don’t feel that it is truly necessary to have children, then they will generally have fewer. All the government subsidies and programs to increase the number of children, especially among the cognitive or social elite, will fail if the potential parents don’t have a felt need to have more children.