Focusing on Healthcare’s Administrative Costs Is Misguided

Substantial thinking about healthcare reform starts with acknowledging that administrative bloat isn't the big problem

It’s frequently argued that the problem with America’s healthcare system is that there’s too much administrative overhead, and that it’s fallen behind other systems as a result. The people who argue this position are generally not doing a good job of quantitatively reasoning about the issue, because it is blatantly untrue.

Administrative Bloat is Popularly Overstated

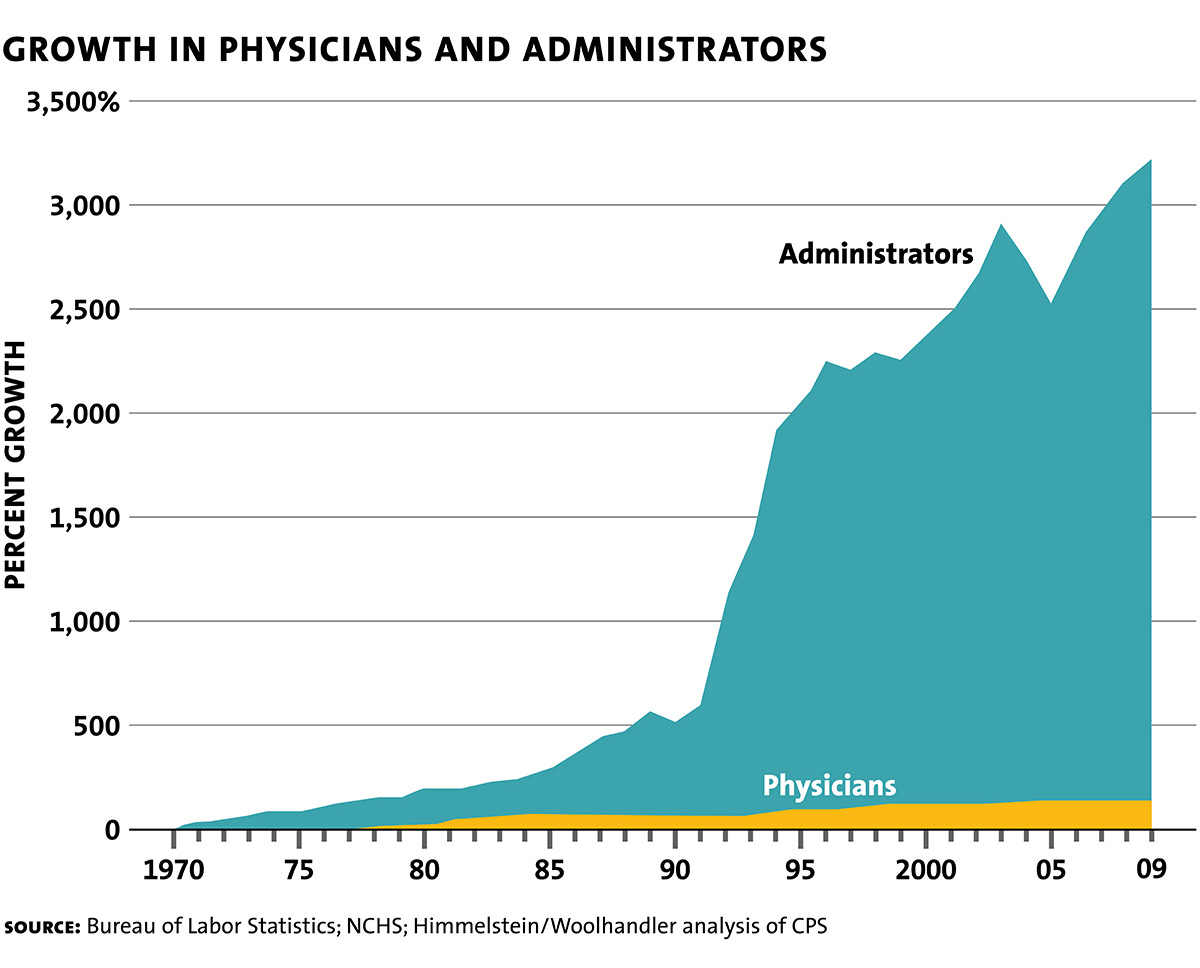

This chart and charts like it are famous, but they should be infamous. They appear to display an incredibly large increase in the number of administrators in the U.S. over time, and the insinuation is that these are driving America’s high healthcare spending.

Alex Tabarrok suggested that this chart displays an incorrect number of administrators in 1970 and a change in definitions around 1992, resulting in a graph that’s extremely off the mark. This is easy to believe, because the numbers from Woolhandler and Himmelstein don’t line up with the huge jump shown on the chart. In fact, Alex noted, “between 1989 and 1994, [Woolhandler and Himmelstein’s reported] share of health care administrators as a percent of the health care workforce increased from 25.5% to… wait for it… 25.7%.”

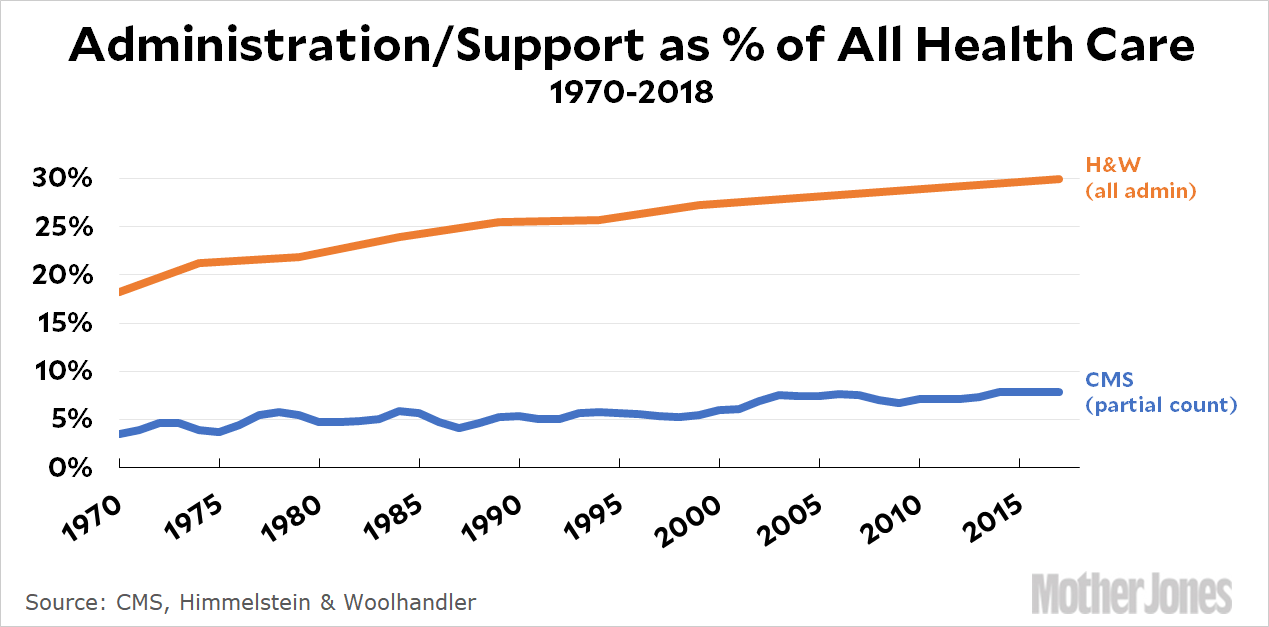

Something is amiss with this chart, so Kevin Drum sought to figure out what it should really show. Using using various clear and credible sources, he found that there wasn’t any room to support that graph, regardless of how you try to measure health care administration costs or administrator numbers. But more critically, the proportion of administration and support as a part of total health care costs barely rose using estimates from either the CMS or Woolhandler and Himmelstein.

While this increase is still sizable in relative terms, it probably doesn’t signal anything all that bad about administrators in healthcare. The reason is that things have changed:

In 1970, the health care industry spent approximately $0 on IT management. Today they spend a bundle, and all of that is admin overhead. Purchasing has exploded too, since there are far more things to purchase these days. Regulations have grown along with technology, so compliance offices have grown. Doctors and hospitals have always spent hours on the phone arguing with insurance companies, but that’s probably grown too.

Administrative Bloat in the U.S. is Not Uniquely Bad

If you want to blame administrators for high American healthcare costs, you won’t get far, because you’ll quickly run into how much the costs are and how they compare to the costs faced in peer countries. As it turns out, America’s spending on administrators is in line with the spending of other countries, America is just richer:

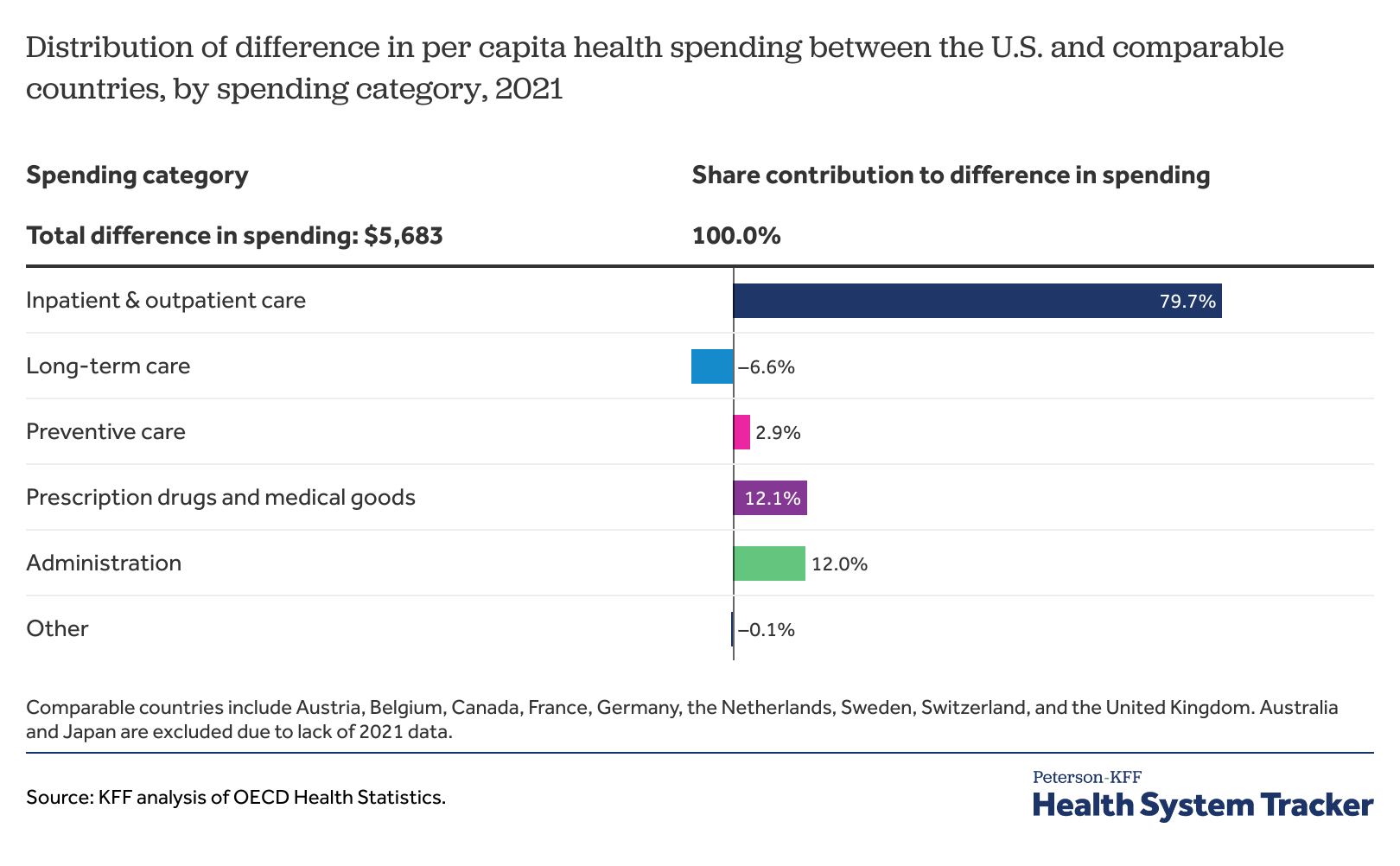

America also spends much more per capita than its peer countries, and when you just measure the sources of the differences in spending, administration makes a relatively small contribution:

The real source of differences in costs is not administration, it’s payments to providers, including hospitals, doctors’ offices, clinics, and so on. Although to be clear, this measure provided by Peterson-KFF is payer administrative expense, and provider administrative expense is rolled into the other categories. If you want to get a very maximal estimate of what’s on the table by eliminating administrative bloat, you’ll have to look to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The CBO estimated that transitioning to a single-payer system would reduce administrative costs within the healthcare sector by 1.8% of 2030 GDP, or a percentage approaching $500 billion today, or about 11% of all healthcare spending in 2022. Moving to such a system would eliminate most of the work done by insurance staff, medical billers, coders, and so on as a result of extreme simplification.1 Such a system would also force down physician pay and could generate savings in other areas while forcing people who are currently misallocated in healthcare administration into the wider economy where they can be more productive. Keep in mind that it would do so while generally reducing the availability of care and quashing America’s place in the world as an engine of healthcare innovation. That is a trade-off most Americans probably wouldn’t like to see, so while this provides us with a plausible upper-bound of administrative costs and it can reassure us that administrators are not really America’s ‘big problem’2, it’s still not a politically viable fix to America’s high healthcare spending.3

Good Governance Can Address Administrative Bloat

Private equity firms bring excellent corporate governance incentives to the firms they acquire, and this is true for diverse businesses, like airports and fertility clinics, as well as for hospitals. It was recently found that when private equity acquired hospitals, it tended to lead to a small increase in profitability with no visible impacts on care volume, revenues, patient mix, core worker (nurses, pharmacists, physicians) employment, or patient outcomes. How?

Right after acquisitions take place, the impact on core worker employment is negative, as they make the choice to leave for more amenable arrangements. But after a few years, it rebounds and the acquisition leaves behind no significant impact on their employment numbers:

The real employment impact is on administrative workers, whose numbers continuously decline through almost a decade after acquisition:

Private equity hospitals save money through this route, and also through reducing administrative wage rates, while preserving the wages for core workers: In the short-term, the core wage rates nonsignificantly increases, and in the longer term, it nonsignificantly decreases, all while administrative wages significantly decline, by a bit over 7%. Putting these changes differently, the number of core workers per patient is unchanged in the long run after acquisition, while the number of administrative workers per patient declines substantially, without affecting heart attack or failure numbers, pneumonia infection numbers, readmissions for those conditions, or much of anything else, including the number of available beds, patient numbers and sales, the outpatient ratio, the proportion of patients using Medicare or Medicaid, and anything to do with the case mix index.

In short, private equity is very likely identifying hospitals that actually are spending too much on overhead and it’s turning them profitable not by charging or doing more, but by cutting the admin by about 13% over eight years on average. The amount this increases gross margins is about 2pp, while operating income goes up by 6pp, and the return on assets increases by 5pp. Compare this to non-private equity acquisitions, and the differences are stark. For example, those reduced the numbers of core workers by nearly 30% by the end of the observation period, and they generated smaller returns, with more potential patient downsides.

Nothing really beats good corporate governance—not for success, nor for providing us reasonable estimates of the scale of administrative burdens. The scale implied by private equity acquisitions, by the way, is too small to explain America’s high healthcare costs. These acquisitions show that administrative bloat can be considerably reduced, but they don’t say that private equity is perfect or that there aren’t areas in which it’s made mistakes or elected to push up prices.4 They tell us a lot about how far we can expect to go cutting out unnecessary admin, and how the amount we can reasonably expect to save is something, but it also just isn’t that much barring significant reforms.

What Policy Actually Addresses Administrative Bloat?

Short of transitioning to government-managed care or promoting more vertically-integrated care, what policy would reduce America’s administrative bloat issue? The obvious answers are all removing rules that mandate administrators or otherwise make it hard to do without them, but here’s the rub:

That doesn’t go very far;

Other countries suffer similar levels of administrative bloat, they’re just poorer.

If you have ideas, feel free to tell me, because I’m just not seeing them, nor am I seeing how they’ll make a big difference anyway.

More Ways to Reform the Healthcare System

If you want to actually reduce costs and improve the quality and availability of healthcare in the U.S., I recommend reading this, by Lawson Mansell; this, by Helland and Tabarrok; this, by Mitchell and Koopman; this, by Cicala, Lieber and Marone; this, by Thierer and Wilt; everything related to this; this and this by Michael Abramoff; this by Michael Cannon; and really, so much more. There are reform ideas aplenty, and they can save the healthcare system trillions while improving the quality and volume of care if done right, but they almost-certainly will not make things better principally through cutting administrators and other perceived ‘middle-men’ out of the mix.

June 29 Update: Fragmentation Nothingburger

David Cutler has long claimed that the healthcare system would save a lot of money if payers and providers used standardized billing processes. Writing for the Hamilton Project, he suggested that there would be substantial cost-savings with the establishment of an automatic clearinghouse for healthcare claims modeled after the one in banking.

While plausible, there’s hardly been any empirical evidence to support Cutler’s clearinghouse idea until recently. A new preprint on the topic just came out, and it suggests the need to temper our expectations.

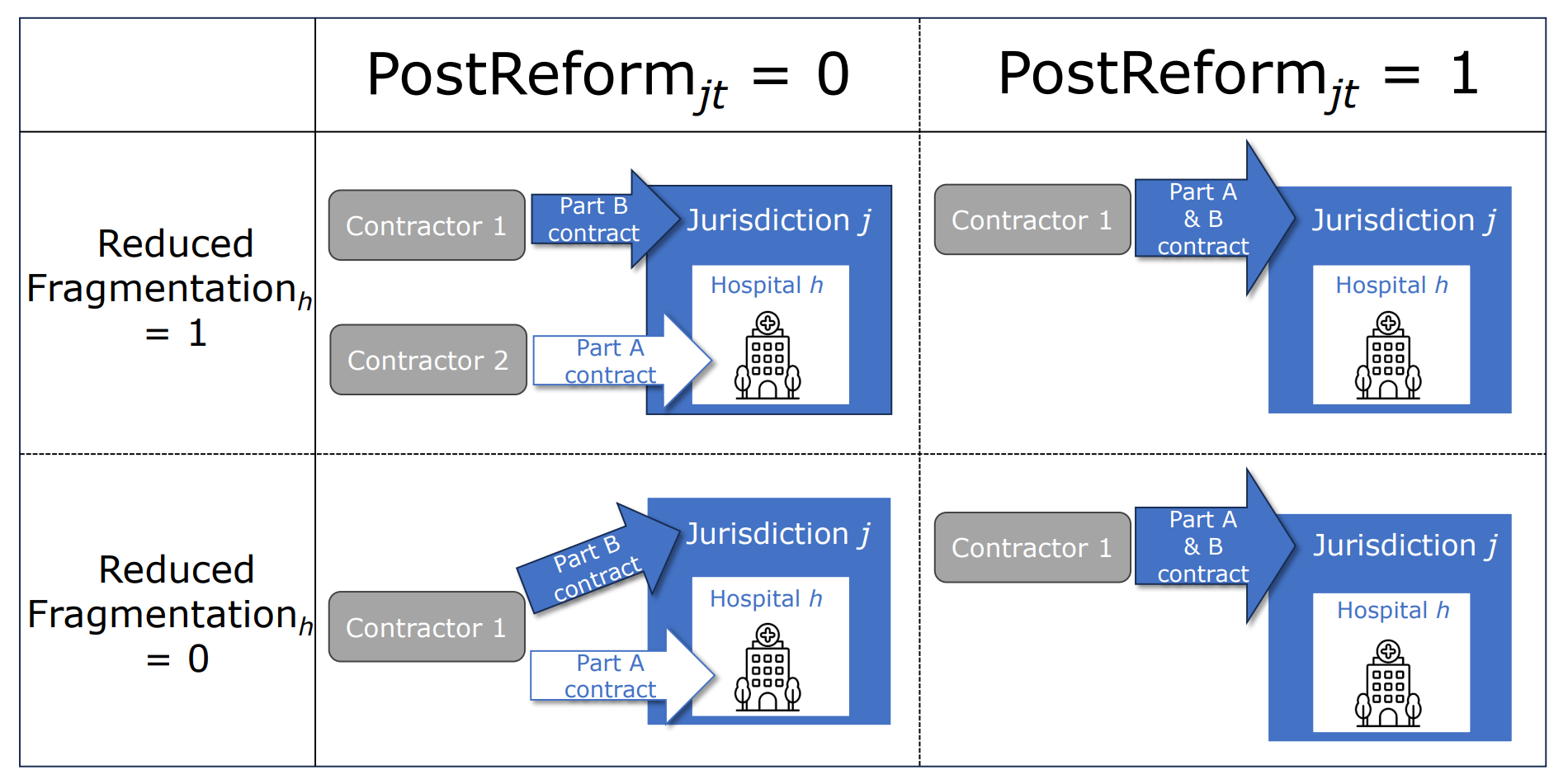

The preprint deals with the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 reforms that created modern Medicare Administrative Contractors, or MACs. MACs were supposed to remedy the heavily fragmented situation Medicare was facing, where they contracted out Part A and Part B administrative services to different entities—”fiscal intermediaries” for A and “carriers” for B. The CMS-chosen carriers filled an administrative role across regions and the intermediaries were nominated by groups of providers, approved by the HHS, and then set to task, creating a situation where, often enough, an individual patient would have to deal with multiple firms handling different claims. Under MACs, a single regional contract handles claims for Parts A and B, greatly simplifying the whole process.

Like most Medicare reforms, the rollout was not immediate. The scheme kicked off in 2006 and it reached completion some eight years later.

The rollout was practically random with respect to geography, which combined with its staggered nature, is a major boon for econometricians, since it provides lots of identifying variation to work with. The rollout also accomplished its goals and did, in fact, simplify medical contracting. The share of admissions with multiple contractor encounters falls substantially the moment after the reforms are in effect, albeit with some lead-in. The effect is to halve the likelihood of multi-contractor contact.

The reform had one notable effect beyond its big effect of reducing administrative fragmentation: it somewhat reduced rates of claim denial. Some level of reduction in the frequency of claim denials is expected purely as a result of reducing the number of points of friction patients have to deal with, but intuitively at least, a 50% reduction in the probability of encountering multiple contractors sounds like it should do more than reducing denial rates by 2.3 percentage points. Oh well!

What the reform failed to accomplish is much more noteworthy. Shockingly, it didn’t reduce bill processing time by more than 1%. The number of inpatient stays, total administrative spending, administrative salaries, information technology adoption, patient spending and provider encounters, and even readmissions, were all unaffected.

Simply put, there were no meaningful effects of pretty sizable reductions in administrative overhead and confusion. Having a single contractor handle inpatient and outpatient care billing instead of multiple definitely reduced administrative fragmentation, but the benefits stopped there—so much for the clearinghouse, so much for the powerful role of billing heterogeneity.5

While other administrative reforms might be more effective, going from two to one claims handlers wasn’t. It’s possible that larger fragmentation reductions among private payors will have some effect, but it seems doubtful that effects could be very large given this example. For the purposes of reforming healthcare’s administrative costs, it’s probably time to look elsewhere than this style of fragmentation.

The dollar value implied by the CBO here is unrealistically large. I am aware of this. They have assumed greater savings than are possible, which is why I am presenting this as a very hard upper-bound. Even if you take all insurer-side administrative costs and all the costs borne by hospitals, providers having to have massive billing departments, negotiating with different insurers, etc., you’re still south of their number.

With some caveats and clarifications for additional precision about what quantities are being described.

Although a single-payer system would almost-certainly reduce administrative burdens, it’s likely you could still do better in a market system if you simplified the contracts between physicians and insurers. As Scheinker et al. wrote:

Though we find that a single-payer system will reduce certain administrative costs, we also find that reforms to our current multi-payer system could generate at least as great a reduction. There might be benefits to pursuing national health reform, but we can reduce burdensome administrative costs through much simple and less disruptive paths.

It has. For example, PE acquisitions of nursing homes have been deleterious to patient health. It’s easy to imagine why. Just think of what might happen to health if janitorial staff are cut, or care workers who flip people in their beds are pushed out. The things that seem to be low-hanging in nursing homes are, I think, more likely to be things that might matter more than a PE partner thinks. Looking outside of healthcare, PE acquisitions have also been harmful to student outcomes. Again, makes sense to me. PE partners probably have preconceptions about education that mean larger tradeoffs for students when you act on them.

Looking back at healthcare, there’s evidence that physician management companies—which are often PE-backed—worsen the notorious habits of anesthesiologists, allowing them to charge higher rates for the same services. They promote higher allowed charges, higher unit prices for charges, and a (nonsignificantly) higher probability that the provider is listed to the insurer as being an out-of-network one, leading to more surprise billing for patients:

Can you blame them? Everyone knows anesthesiologists’ deservedly bad rap for doing an easy job while extracting high rents from insurers, patients, and the healthcare system in general. That PE is aware of this and exploits it shouldn’t be surprising to anyone. Market power makes anesthesiologists capable of doing bad, and PE can make that market power worse. Couple this with things like Certificate-of-Need laws, or the lack of site-neutrality in Medicare payments, and it’s shocking that the whole healthcare system isn’t owned by like five companies.

The solution to bad PE behavior is to fix the bad incentives that PE companies exploit, because that is what they’re often doing. Once those are fixed, PE involvement will be more like the general case of hospitals, where they’re visibly not impacting much of anything, they’re just profiting through optimizing, and that’s a good thing, for them and, through releasing administrative workers, for the economy as a whole, even if there are no savings passed on to patients.

Referring to heterogeneous claims handling.

Interesting article. As a healthcare administrator, seems to me the best way to reduce healthcare costs at the personal level is to create more providers. There’s an intense shortage, driving up salaries restricting access. Additionally, this limits their ability to help intervene in patient care early enough to prevent longer term issues that cost more to solve.

Please apply to work at DOGE. Seriously. You'll be writing articles about their decisions anyway.