Food Deserts Are Not Real

They're more like bad habit neighborhoods

Today’s post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

Parents, have you noticed your kids like certain foods more than others? I’m certain you have. For the rest of you, trust me, there are studies affirming that people of all ages—not just kids—have food preferences that influence what they choose to eat. On a related note, have you ever heard of food deserts?

Food deserts are areas where there’s limited access to fresh, nutrient-dense foodstuffs. Residents of these areas have to make do eating fast food, heavily processed microwave meals, soda, and other not-so-healthful items, resulting in food deserts having high rates of chronic illness and obesity if residents aren’t willing to travel the, sometimes prohibitively far, distances required to partake in the high-quality grocery shopping that higher-income households are more likely to enjoy. That’s the common narrative about food deserts, at least.

There is definitely some truth to the idea. The areas defined as food deserts do feature higher rates of obesity and poverty, and one of the hallmarks of food deserts—fast food joints—predicts eating fast food, whereas supermarket access predicts the opposite.1 There’s also evidence that systematic initiatives to promote grocery access in these sorts of underserved areas are lacking.

There is also some natural experimental evidence on the impacts of supermarket openings on purchasing and consumption decisions.

Elbel et al. examined the effects of a new supermarket opening up in the South Bronx due to tax and zoning incentives on “high need” individuals in the area. The effects? After a bunch of tests, there were two marginally significant changes: supermarket shopping increased by 2 pp., where the baseline usage was 94-97%, and there was a 20% decrease in sugary beverage consumption. In a separate study of two neighborhoods in the Bronx, Elbel et al. applied a difference-in-differences design to compare residents of Morrisania and Highbridge before and after the former received a new supermarket. Food intake was not affected. Similarly, Singleton et al. compared communities in Rockford, Illinois who were or were not subject to the Healthy Food Financing Initiative—a program to support healthy food purchasing in “low-resourced communities across the United States.” They measured food availability and promotions and found a marginally (p = 0.04) higher availability of frozen vegetables after the initiative was in place.

These sorts of findings are commonplace in the empirical food desert literature: objectively increasing availability and access to food doesn’t seem to do much to what people choose to eat or what food is considered available. To understand why, we need to look at some other results.

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

Who Counts Calories?

Many cities in the U.S. now have calorie label mandates. The way these usually work is to force local restaurants to provide calorie information for their menu items.

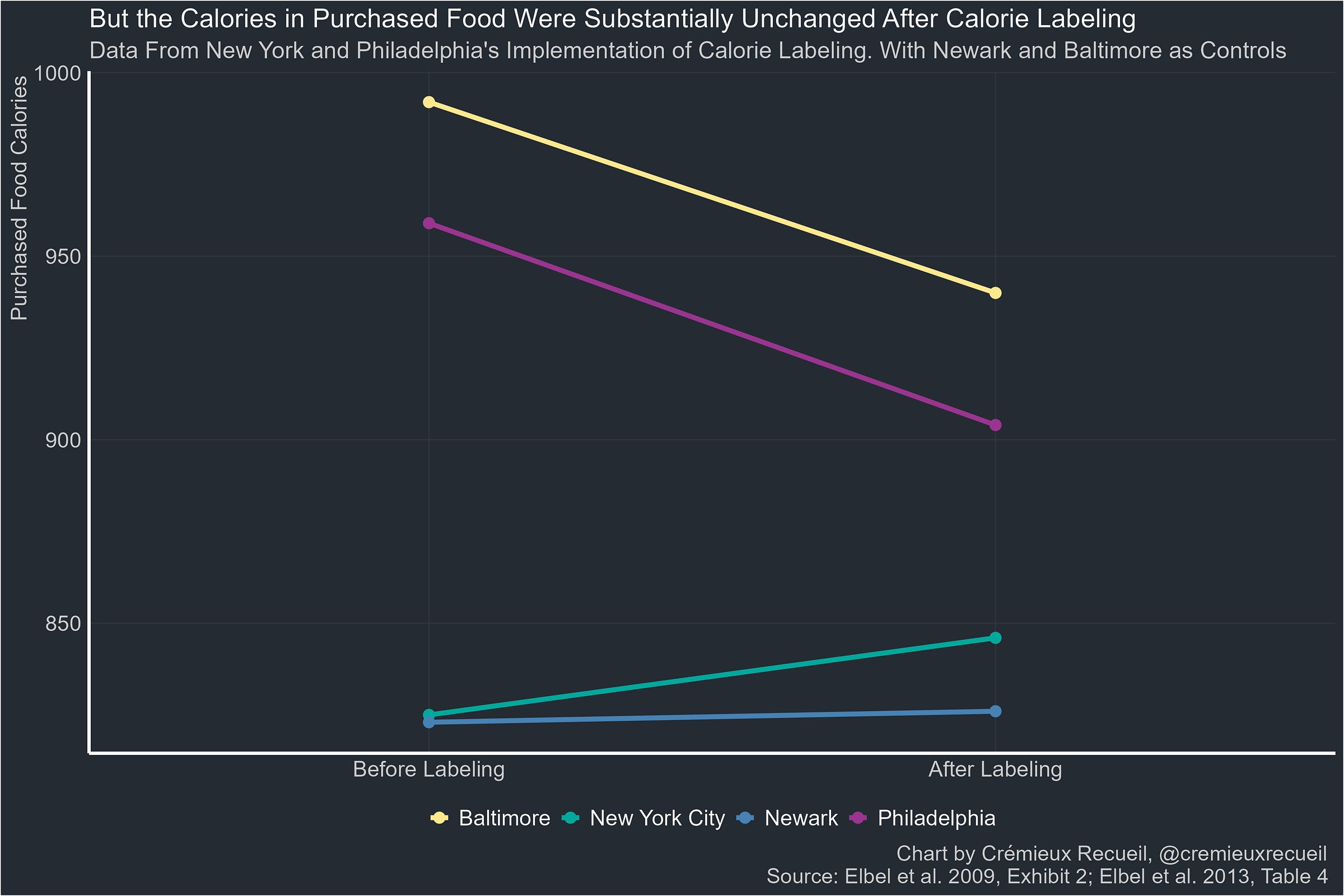

When calorie labeling mandates were implemented in New York and Philadelphia (Newark and Baltimore shown as comparisons), people noticed. People also claimed that calorie labels influenced their purchasing decisions, and they claimed that the direction of influence was generally towards buying fewer calories.

But what, in actuality, happened to their observed calorie consumption? Not a lot! In Baltimore and Philadelphia, calorie consumption fell by similar margins, but Baltimore didn’t have a mandate. Similarly, New York City saw an increase in calories purchased over non-mandating Newark.

People said they did one thing in response to the calorie labeling mandate, but they really didn’t. That’s normal, but it’s a surprising finding if you believe people do what they say they do when it comes to eating behaviors. On the other hand, this set of findings is not really surprising if you believe people have food preferences and habits that are hard to change.

Now let’s talk about food deserts again.

Structural Modeling Food Deserts

The most extensive and decisive work on the topic of food deserts leveraged thirteen years of grocery store openings and Nielsen Homescan data on people who moved between different geographical areas to fit a structural model explaining why the people in food deserts make different food purchasing decisions than the people elsewhere do.

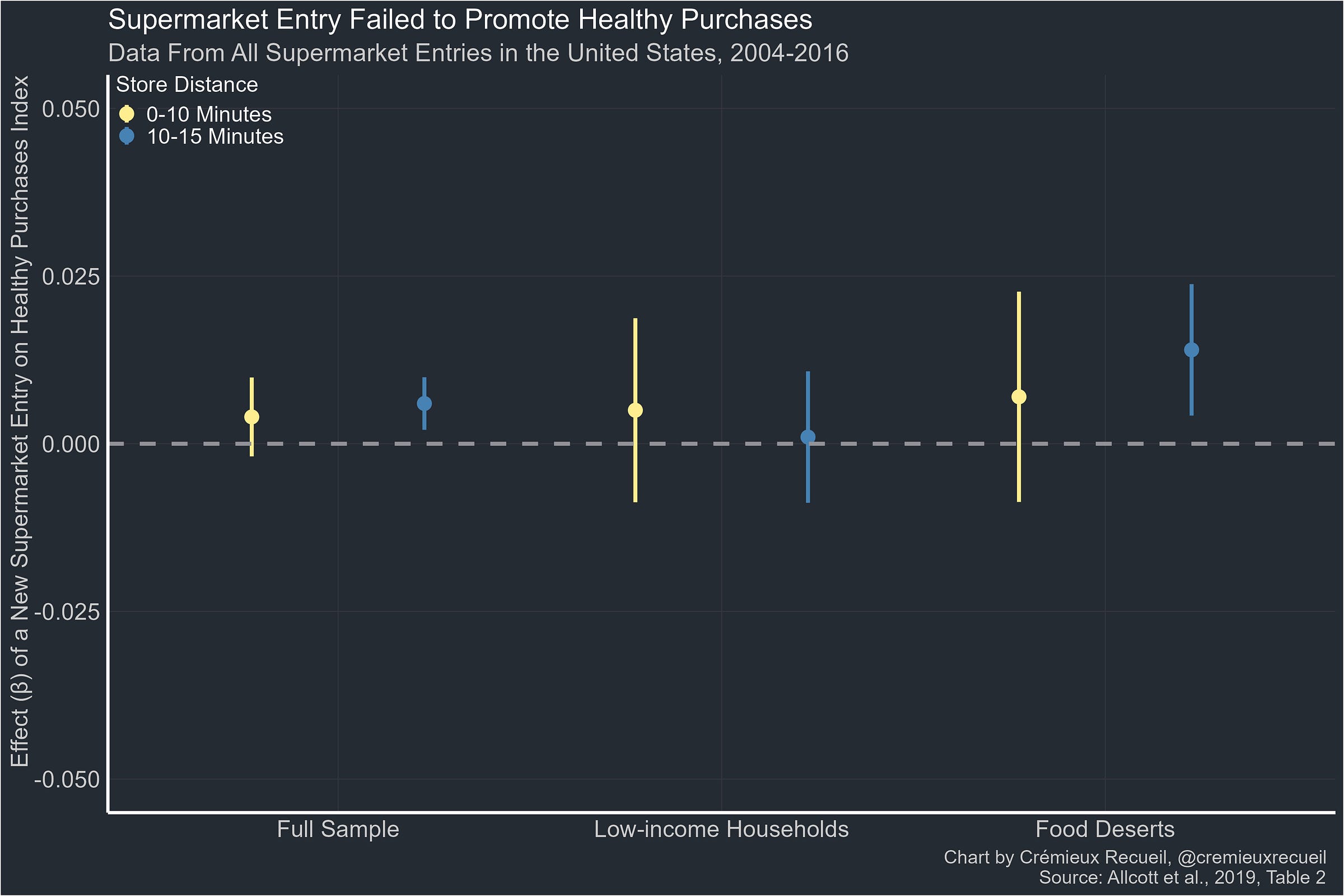

To get to the structural model results, we have to look at some other results first. Using supermarket entry data, the effect on healthful purchases was estimated to be minimal for openings within 0-10 or 10-15 minutes, with no significant effects for low-income households at all, and only a meager effect in food deserts, but curiously, just for stores 10-15 minutes away rather than 0-10.

When supermarkets entered an area, people did shop at them, but they also didn’t seem to shop less at preexisting stores.

The effect of new supermarket openings is to grab a share of local grocery sales, but the effect on healthy eating is glaringly absent, in total, among low-income households, and in food deserts specifically.

The Nielsen Homescan data on people who moved between locations with different levels of typical food consumption healthfulness also suggested that the impacts of local supply on healthful purchasing are minimal. Movers who changed zip codes saw medium-term place effects on the healthfulness of their purchases explaining no more than 2% of the high- versus low-income difference, and movers across counties saw medium-term place effects explaining no more than 3.2% of the difference.

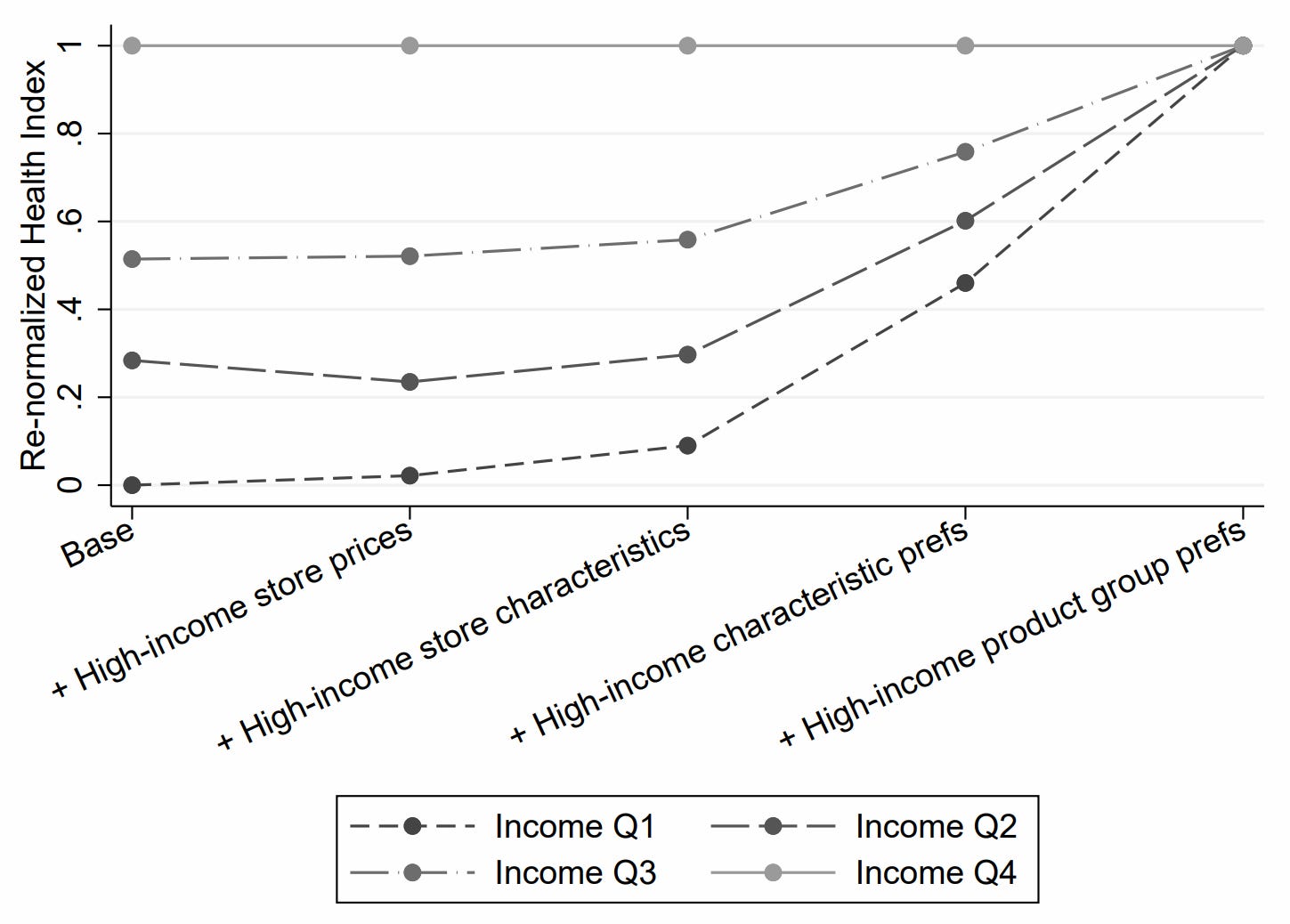

So with these findings in mind, what would it take to make households at all income levels make equally healthy food purchasing decisions? Going from left to right, we get our answer:

At baseline, there’s a large gap in food purchasing healthfulness, and scaling the lower-income groups’ prices to the level observed in the highest-income group does little to change that. Setting the available product nutrient quality to be equal also doesn’t do much either, but giving the different income groups identical nutrient preferences does start to make a noticeable difference. Finally, the gap between households with top and bottom incomes is virtually eliminated (reduced by 88-93%) after matching them on their product preferences.

Eat That

The reason food deserts are places where people make so many unhealthy food decisions has little to do with supply and a lot to do with demand. The people living in those places just like eating in ways that are not healthy, for whatever reason. It might be easier to eat processed junk, it might taste better, and much else fits the bill. Those people like eating things that aren’t very nutritious on their own, and to get from there to obesity, we also know they like to eat a lot. In fact, eating a lot is really the only way to get to food deserts having an obesity problem, because the people living in them don’t eat that much less healthfully, so they must tend to eat excessively.

So here’s my advice if you were taken in with the narrative that food deserts are to blame for a big part of the income-health gradient and the obesity crisis. If you want to change the habits of the poor, downtrodden, obese people who disproportionately live in the areas social scientists have dubbed “food deserts”, then you should support UBO: Universal Basic Ozempic.

Two notes.

First, this may not predict being fat.

Second, it also seems to be the case that food deserts don’t attract dollar stores, but when dollar stores enter the area, they might repel supermarkets.

FWIW, George Orwell gave the standard left wing explanation for this demand phenomenon in The Road to Wigan Pier:

"Would it not be better if they spent more money on wholesome things like oranges and wholemeal bread or if they even, like the writer of the letter to the New Statesman, saved on fuel and ate their carrots raw? Yes, it would, but the point is that no ordinary human being is ever going to do such a thing. The ordinary human being would sooner starve than live on brown bread and raw carrots. And the peculiar evil is this, that the less money you have, the less inclined you feel to spend it on wholesome food. A millionaire may enjoy breakfasting off orange juice and Ryvita biscuits; an unemployed man doesn't. Here the tendency of which I spoke at the end of the last chapter comes into play. When you are unemployed, which is to say when you are underfed, harassed, bored, and miserable, you don't want to eat dull wholesome food. You want something a little bit 'tasty'. There is always some cheaply pleasant thing to tempt you."

The personal finances and fitness/health decisions are correlated in an utterly intuitive way: some people optimize for the short-term over the long-term: they favor things like ultra palatable and convenient food with long-term bad health consequences (such as ultra processed carbs with lots of added refined sugar). They favor things like frivolous consumption over saving and investing. They congregate in certain areas. Others take short-term costs -- bothering to make healthy food that is great long-term but less convenient and palatable. Consuming a lower percentage of their income to save and start businesses with long-term potential. They live elsewhere. Both are perfectly fine. You get what you get. So the fitness and finances should pretty much go together. And for profit businesses designed to serve respective groups should go where they're demanded.

The only annoying thing about this wholesome and expected pattern is when people pick the short-term over the long-term then want to re-trade when you get to the long-term. Hell no! You got cheesecake for breakfast and spinning rims on your car ten years ago. Those were the prizes. I hope that they made you happy. But there should be no surprise or scandal if they result in obesity and poverty. It was a decision to be fat and poor. Behaviors, habits, and decisions are not 100% of the story. Perhaps only 99%. But they're the 99% that you can do anything about so the part worth focusing on. Perhaps grocer treachery is some (certainly <1%) of the story but the evidence looks pretty sparse; instead it looks like the effort to make short-term decisions then complain when you get to the long-term and got your prize a long time ago.