How Many Sexual Misconduct Allegations Are False?

An Anonymous Guest Post

Sexual harassment seems to be everywhere. According to activist sources, 81% of women have experienced some form of sexual harassment at least once in their lifetime. After the 2016 #MeToo moment, sexual harassment awareness is at an all-time high. There is hardly a man of any fame or significance, who has not been accused of sexual misconduct. From President Trump and Justice Kavanaugh, to Johnny Depp and Marilyn Manson, no one seems to have escaped accusation. Young professionals in Western countries are advised to check their sexuality at the door, and everyone has a colleague who has lost his job over a harassment allegation.

But how many of these accusations are actually truthful? The case of Johnny Depp v. Amber Heard certainly made the public think twice about the substance of many sexual abuse allegations. More recently we had the case of Andrew Tate, who was imprisoned for four months without having been formally charged, on allegations of sexual violence. Amongst those with first-hand experience of sexual assault cases, there is widespread disbelief in their validity. On average, police officers think that half of rape accusations are fake. But what do the data say?

A casual Google search will inform you that only 5% of sexual harassment accusations are false. Google points us to a website set up by Brown University, which purportedly debunks the “myth” of false accusations. The first page of Google also contains results from the most prestigious outlets (CNN, BBC, etc.) which seemingly unanimously repeat the 5% number. Some media go as far as to inform us that “Almost No One Is Falsely Accused of Rape”.

All of these outlets cite the same study, which also happens to be the first academic paper returned by Google (and any other search engine) on the topic: Lisak et al. (2010). This is a rigorous study by David Lisak, a retired professor and anti-rape activist who was himself sexually abused as a minor. The study examines every single sexual assault claim made at a prestigious American institution (Northeastern University), over a 10-year period. Of the 136 cases, only 8 (5.9%) turned out to be false. This percentage is confirmed by a 2015 meta-analysis, which found the average rate of false reports to be 5%. Case closed? False accusation myth debunked? Not so fast!

As you can see in this overview of the studies included in the meta-analysis, there were just seven studies and they were all published prior to 2016, the beginning of the #MeToo movement. Only one was published post-2011, which is when the U.S. federal government began to encourage lower standards of evidence for accusations of sexual assault on campus (through the now-infamous “Dear Colleague” letter1). One of the seven, with the second-largest sample size, was not even a published paper, but a “personal communication”! Another is the famous Lisak et al. study.

To illustrate the weakness of these studies, we’ll turn back to Lisak et al. The first drawback has already been noted: the study covers the decade from 2000 to 2010, which was truly a different era when it came to sexual harassment accusations. Universities were not under pressure to punish students for sexual misgivings and #MeToo wasn’t in vogue. But the devil is in the details of how “false accusation” is defined, a problem common across all relevant studies.

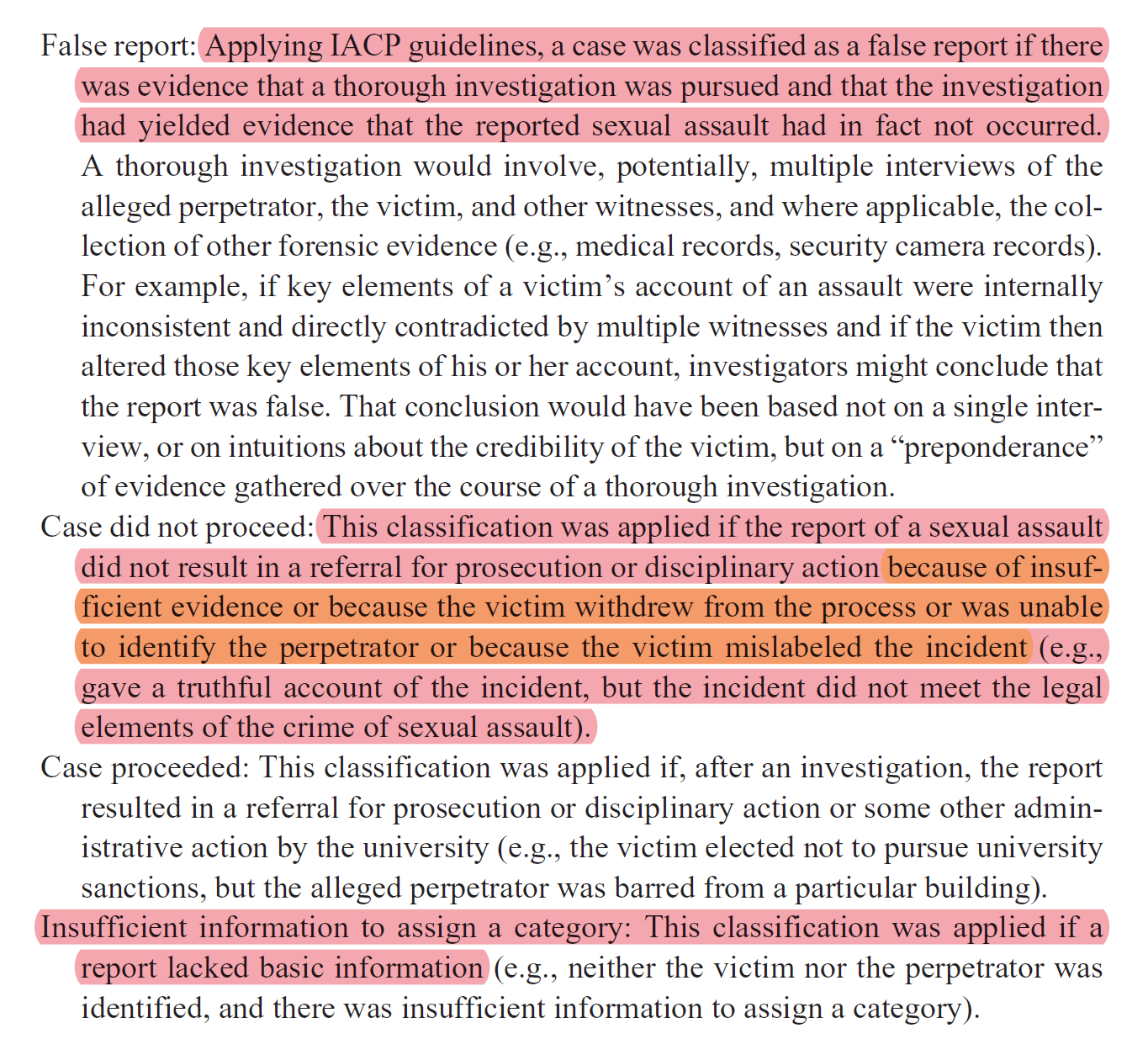

According to their own description, a claim can only be described as false if it made it to the prosecution stage and was then proven to be incorrect beyond any reasonable doubt (this used to be the standard before the government forced universities to abide by the “preponderance of evidence”—which in practice means that the accused is always guilty). If we estimate the proportion of false claims as a subset of those cases that made it to prosecution (following the authors’ definition), then the percentage shoots up from 6% to 14%. But that’s not the full story. A full 45% of cases did not even make to the prosecution stage because of insufficient evidence. These claims may not be considered “false” under the legal definition, but they are certainly unsubstantiated under any common-sense framework.

From that study, all we can conclude is that 35% of accusations have any substance to them. And we may assume that some of those cases that made it to prosecution were eventually dismissed, so the real percentage of truthful sexual misconduct accusations could be even smaller!

In conclusion, a single study is used across all mainstream sources to state that false sexual misconduct accusations are rare. A close reading of that study reveals that the majority of sexual misconduct complaints were actually unsubstantiated, even before the advent of #MeToo. Unfortunately, this problem also affects every other study on the topic: rather than estimating the rate of false accusations, they only ever estimate the rate of confirmed false accusations. This topic requires further research, but we are unlikely to witness any, due to the tremendous reputational repercussions faced by anyone who might obtain the wrong result.

This is described in greater detail in Chapter 2 of Richard Hanania’s The Origins of Woke.

Danish data: 7.3% of cases the case is closed with a judgement against the accuser for lying. Same limitations apply as with the data you cite here. The police clearly think there are more lying accusers, but it's not possible to prove. I would trust police's word over the court outcomes, so maybe 30-50% of claims are indeed false.

Danish: https://teknologipartiet.dk/2016/08/22/falske-voldtaegtsanklager-og-retssystemet/

"Most accusations are true" is compatible with "most accusations are legally unsubstantiated" if the legal system sucks at identifying true accusations.