Is There Lead In Your Protein?

And should you be freaking out right now?

Your favorite protein powder might be filling your body with lead.

That’s the takeaway from a new Consumer Reports writeup on 23 common protein powders sold in the U.S. This finding, however, is not new.

Consumer Reports has reached similar findings before and the Clean Label Project recently reported that 47% of protein powders exceeded at least one federal or state contaminant standard for heavy metals including lead. You can find tons of these tests over the years from many different sources and you’ll find the same thing repeated each time: there is lead in your supplements, and there is lead in your food.

Where’s the Lead From?

Lead enters the food supply at various points. The first is in soil uptake by plants.

Plants absorb the stuff from contaminated soil or irrigation water. This seems to be an important source, as indicated by the large differences that different testers seem to find between plant-based and whey protein powders. If you scroll to the diagram above, you’ll notice that plant-based protein powders are far more likely to be violators. If you read the latest Consumer Reports issue on this, you’ll notice that vegan products were the riskiest.

For animal-based proteins like whey and casein, if animals drink water or eat feed that’s contaminated, or they live in polluted areas, that can contribute to contamination in milk or tissue, but this will tend to be less severe than for plant-based powders for a few reasons.

Animal bodies do extra filtering and excreting of heavy metals, reducing the burdens that show up in foods. Heavy metals ingested by animals are also partially sequestered in places away from milk and tissue. Relatedly, if protein is extracted from seeds, legumes, or whole grains (vs. animal muscle), the parts of the plants that tend to accumulate metals are more likely to be included.

There is less cleaning involved in typical plant processing. Ultrafiltration, skim/whey separation, precipitation, etc. discard heavier fractions or precipitates compared to the drying, milling, grinding, filtering, and concentration steps involved in plant protein isolation. To add onto this, in animal proteins, the portion used (e.g., whey from milk, which is a filtered fraction) might inherently exclude heavy metal-rich solids.

Plant-based products also much more frequently use additives, flavorings, and complementary plant extracts, and those are notorious for accumulating heavy metals. Cocoa is an example of this. Notice the result for chocolate protein powders? That’s because cocoa picks up lead after harvest. Raw cocoa nibs are extremely low in lead, but lead appears later—during the fermentation, drying, transportation, storage, etc.—where dust and legacy lead (e.g., from old buildings, paint, leaded-gasoline fallout) can settle on shells and beans. Cadmium on the other hand is taken up from soil into the bean itself. Cacao trees absorb it from certain soils (especially Latin American volcanic/acidic soil) and it accumulates inside the bean.

Cocoa powder being a concentrated ingredient made from cocoa solids, even a modest percentage of cocoa in a flavor system can contribute measurable metals to a whole tub of protein powder. Product surveys repeatedly find that cocoa-rich products have high metal levels. The more cocoa-rich, the worse this will tend to be, with dark chocolate worse than milk. This is far worse than vanilla flavoring.

A major issue for plant-based protein powders is the sourcing. Plant protein raw materials tend to be sourced globally, including in regions with higher soil pollution, heavy metal contamination, and weaker regulation. By contrast, dairy is vastly more likely to be local. This is part of the main issue for cocoa as well, and if you want to be careful about these products, you’ll source them from low-risk regions.

Lead also enters protein powder during harvesting and transport, and it’s cross-contaminated by the equipment involved in that and during processing and milling. Poorly-maintained metal parts can introduce trace contamination and processing aids and reagents can be sources of contamination if they’re not ultra-pure as well. Airborne particulates from other production lines or ambient pollution can also settle into powders or on preparation surfaces. Finally, depending on storage container materials or storage in contaminated environments, trace leaching is possible.

How Bad Is It?

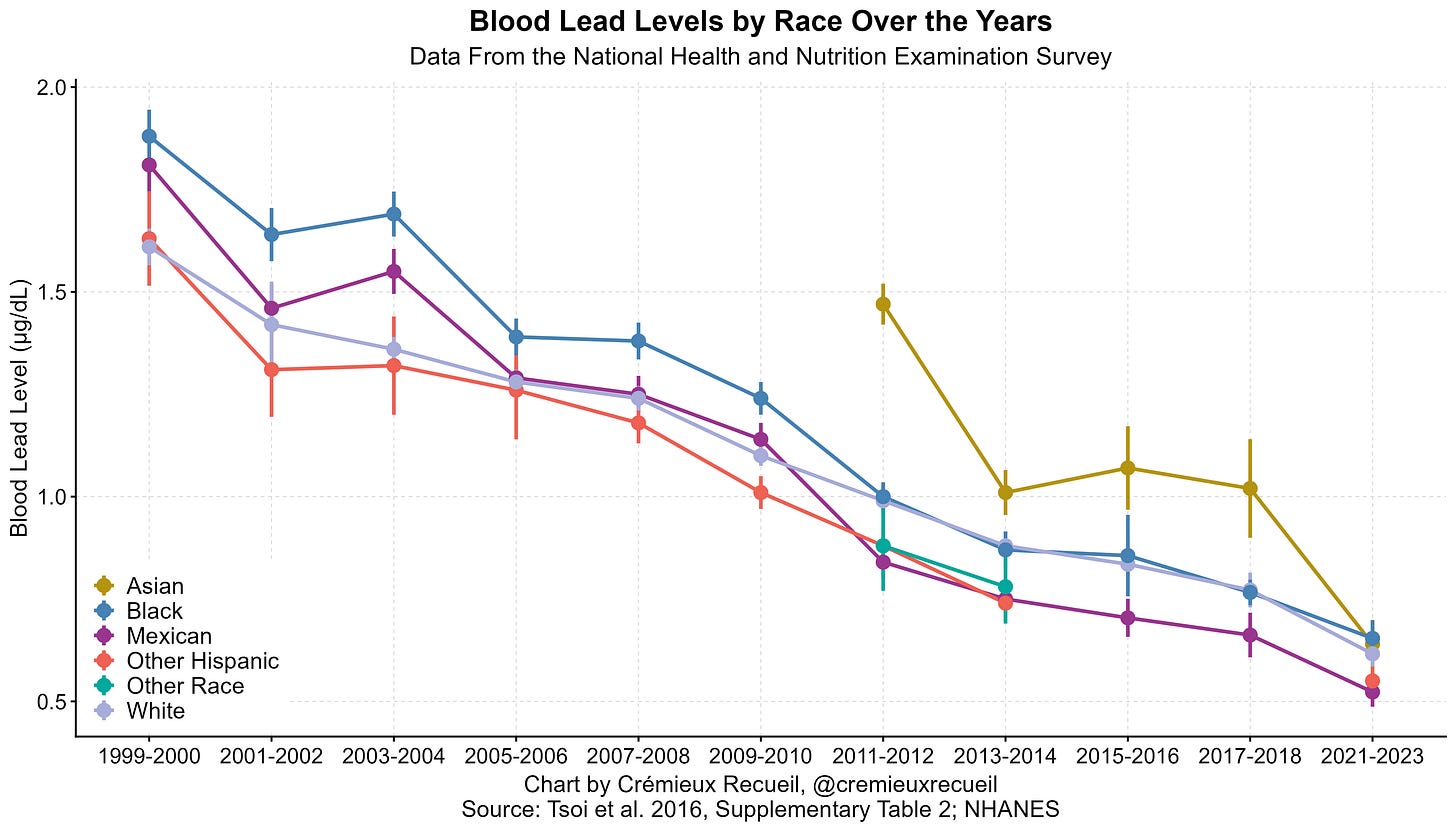

Not bad for lead, and certainly not worse from decades ago. To reassure yourself about the absence of ubiquitous and increasing environmental contamination by lead, just look at blood lead levels over time. Or, go look at levels assessed with any other measure, since they’re all agreed that lead exposure is becoming less common.

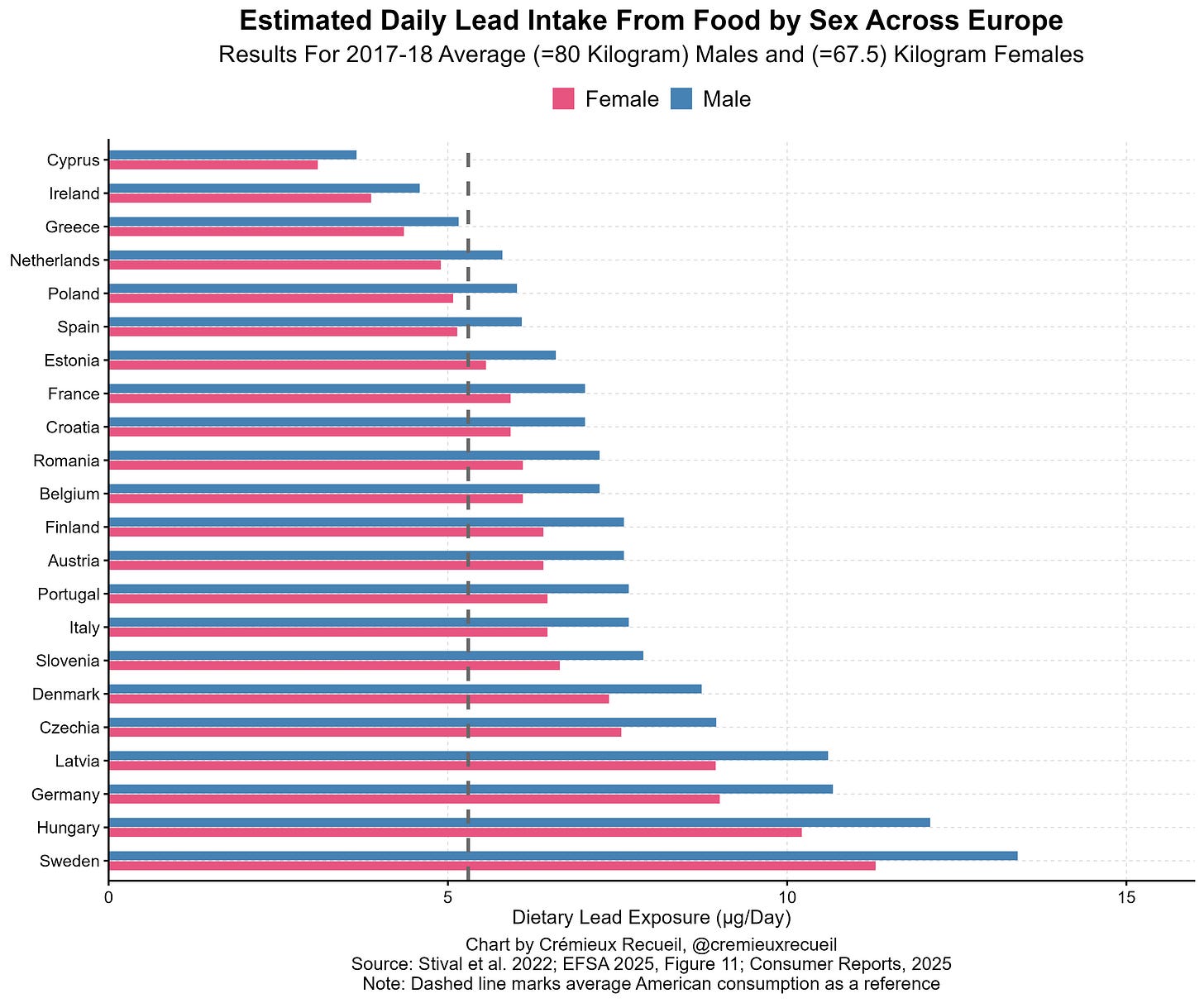

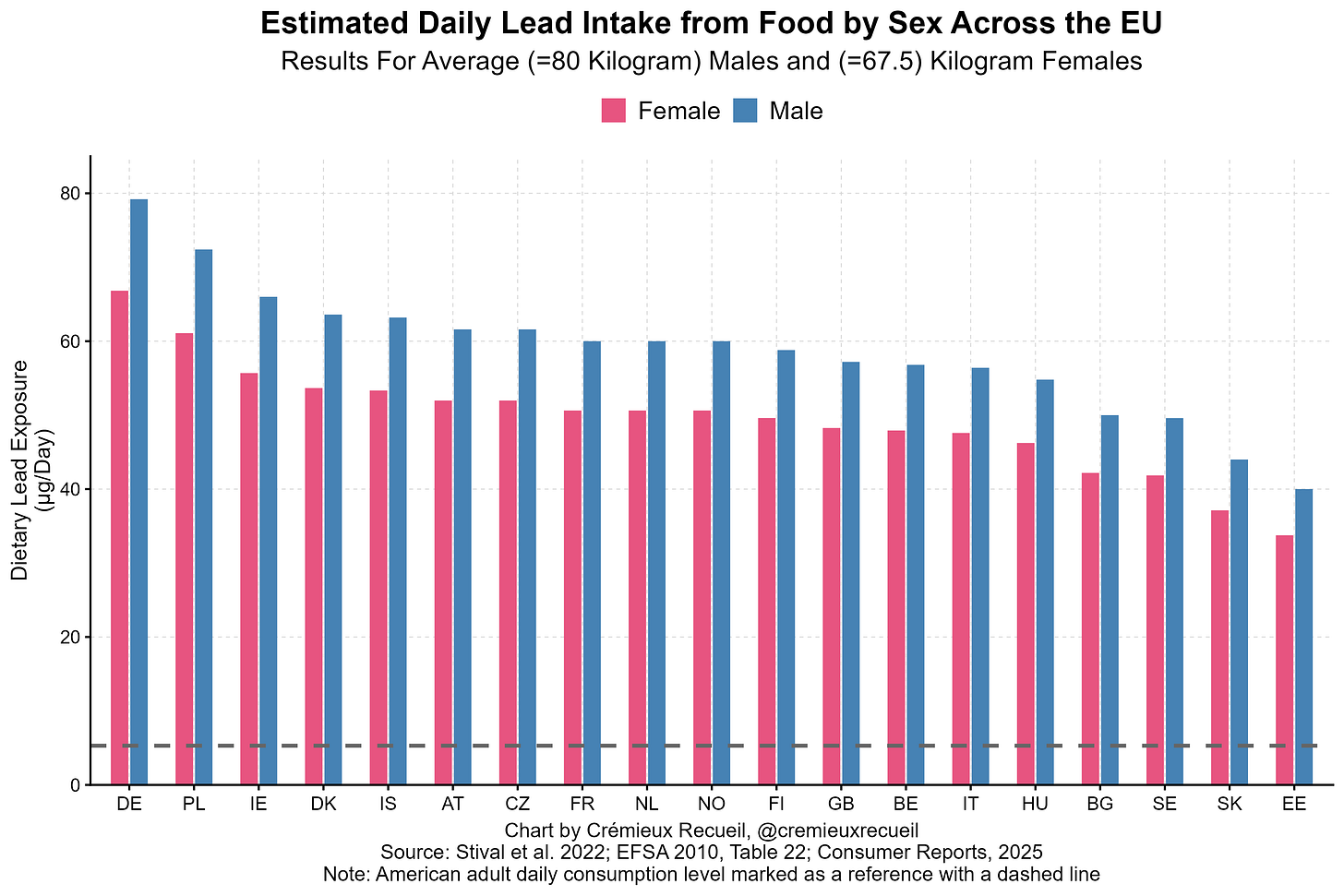

To reassure yourself about contamination in your protein powder, put the Consumer Reports numbers in context. Dietary lead exposure in the U.S. is considerably lower than it is in the EU, and the EU seems to be doing fine. If we don’t agree that Europeans are basically doing fine, then you won’t agree with what I’m about to write.

Two things. First, as Consumer Reports noted, one serving of Naked Nutrition Vegan Mass Gainer—the worst offender in their testing—gives you 7.7 micrograms of consumption, versus the 5.3 micrograms an average American adult gets in a day. Second, using the 2017-18 average European male weight of about 80 kilograms and the average European female weight of about 67.5 kilograms, and coupling that with European Food Safety Authority numbers on average adult dietary lead exposure, we can see that Europeans get much more lead in their diets compared to Americans.1

For an average American man, taking a serving of that gainer plus eating your normal amount puts you below your Swedish counterpart. If you look at Footnote 1, you’ll see that with the values in the EFSA’s 2010 report on the subject, you would need to eat what you normally do plus ten servings of Vegan Mass Gainer to get on Germany’s level. And those places are and were fine! That should help you get a reference level of understanding of the risk you’re facing with these products.

It is still bad to be exposed to lead, and all of these products can and should have less lead in them. But if you think Germans in 2010 were a fine bar for healthfulness, then you don’t have a lot to complain about unless you’re pounding back serving after serving of these products. The more immediately concerning issue than lead—which is what I’ve seen everyone panicking about—is cadmium. The amount of cadmium detected in Huel Black Edition was a large portion even of older, higher dietary intake levels from Europe. There’s no civilized reference sample that is routinely exposed to the amount of cadmium Consumer Reports detected in Huel’s product (9.2 μg/serving).

But what is a safe level of consumption, objectively? References and baselines don’t actually help us to know if we’re being hurt by these products since they are not true counterfactuals. This is something I’ve repeatedly come back to. I wrote a whole article on this topic, but if you don’t have time for it, here’s a summary.

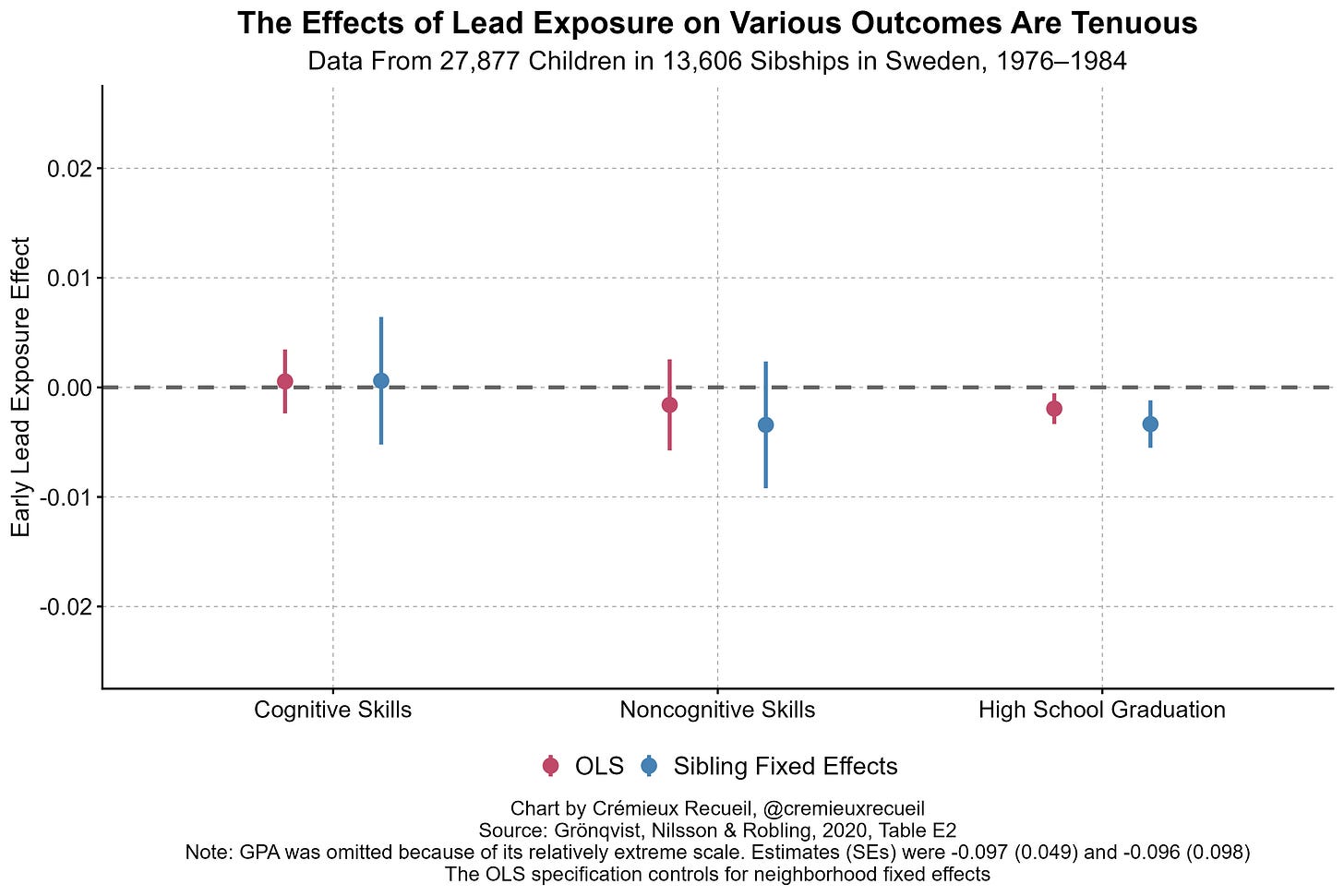

The effect of lead on IQ is overestimated and studies claiming that there’s no lower-bound for negative effects have not been adequately testing their hypothesis. Instead of effects of lead, what they’ve really been testing has largely been stratification of lead exposures by various causes of variation in IQ. Without something like twin or sibling controls or high-quality longitudinal data, it is dubious whether lead effects can be properly estimated at all.

To follow up on that, since we do have one sibling control study, let’s give that a look:

We are dealing with an environmental exposure that is heavily confounded, so knowing what it does beyond its acute effects is tough. When we do get informative studies like this, they are reassuring that lead exposure does not have large effects, at least on important traits like IQ. But when it comes to direct evidence, we are in the dark for so many other traits, and we have to resort to reasoning that, given that lead exposure has declined so much, if it had big effects, the world should’ve changed in a lot of very obvious ways. Instead, what we see is that reducing lead exposure has reduced rates of acute lead poisoning. That’s good, but it’s not a lot.

Some researchers have sought to evaluate the claims from Consumer Reports and the Clean Label Project. One of their important findings was that, if people consumed a serving of the various tainted products each day, their blood lead levels would tend to be higher than what we observe for the general population—that should help to reassure you about mass contamination! The other major conclusion was that the hazards associated with these products are still objectively very low, unless reference levels used by American health authorities aren’t strenuous enough. Keep your European reference in mind, since they’re less strict.

How Bad is Consumer Reports?

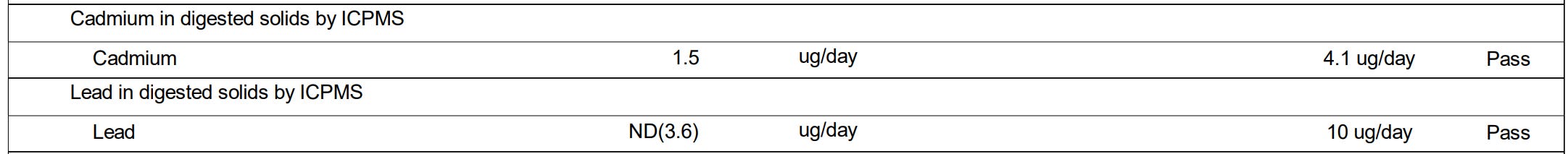

The numbers supplied by Consumer Reports (and many others) might just be wrong. They used common testing methods, but Huel also ran their own testing through the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF), which is recognized as the ‘gold standard’ for testing. The NSF results can be read here.

Take the two big metal results, for lead and cadmium. Consumer Reports says there’s 9.2 μg of cadmium per serving of Huel Black Edition, but NSF says the level is 1.5 μg. For lead, Consumer Reports says they found 6.3 μg per serving, but NSF found a level that was so low it could not be detected at the 3.6 μg tolerance NSF uses.

Both of these findings are:

Well below the level where risk has been shown.

Well within all evidence-based limits.

So what’s going on with Consumer Reports? Maybe Huel supplied a ‘clean batch’ to NSF, but Consumer Reports is reporting what consumers should expect out there in real off-the-shelf product. Maybe there’s large batch-to-batch variance and Huel got lucky, or maybe NSF is acting unethically and their well-earned reputation should disappear. Basically all of that seems likely to be wrong. The idea that lying explains these results is far-fetched because it puts Huel at obvious legal risk when someone does the requisite testing.

We currently do not know what’s up with Huel and their heavy metal contamination levels, but we should lean towards the NSF result, since they are the more reliable authority. NSF’s results also match up with years of testing that has reached similar conclusions. We should also lean away from Consumer Reports, because they are attempting to be the vanguards of standards that are not evidence-based. Specifically, their in-house experts have developed a ‘level of concern’ based on California’s Proposition 65, which in lead’s case, involves taking exposure levels demonstrably associated with risk and arbitrarily dividing by 1,000 to give consumers a risk buffer.

The problem with arbitrary standards is that they are arbitrary. They are not acceptable barometers for consumers to understand health risks. Given how Proposition 65 works, if it’s properly understood, several of these results actually suggest protein powders are fine. Notice how the Clean Label Project’s standard was being above or 2x Proposition 65 levels. That means those products are probably fine.

Consumer Reports’ results also fit in with a large grifting industry that includes a lot of influencers. These influencers frequently go out and use poor testing instruments and inconsistent and unreliable testing methodologies on every product under the sun, in order to claim that those products contain harmful levels of different chemicals that consumers should avoid. Some of the worst examples of this include blackmailing companies to not report results. Others just scare the public. If all these claimed lead exposure levels from different foodstuffs were truly correct, that would show up in NHANES data, but it doesn’t. So take all of these results with a pinch of salt.

The FDA Can Fix This

We shouldn’t even have to worry about this in the first place. We shouldn’t have to question the interests of companies and consumer watchdog groups, but should—if we don’t mind the tradeoff—instead have assurances from the state that this isn’t an issue. To that end, the FDA’s Office of Food Chemical Safety, Dietary Supplements & Innovation should step in and use their ability to set action levels for these products. They have the regulatory authority, they just have to choose to wield it.

They could easily mimic what they’re doing for food for babies and young children with supplements. It would be costly, it would be time-consuming, and it might not be worth it given how well the industry does seem to regulate itself. (Contamination incidents are still remarkable because they are uncommon.) But, though it would not be free, and it might make the market much more limited, if we want true assurances about food quality, this is how we would make sure we get it.

Though Consumer Reports’ evidence for contamination isn’t that great and the reasons for concern on the part of consumers are not that strong, don’t let that get in the way of good fun! As a friend of mine remarked:

on the one hand the science is bad and the whole thing is probably nothing, but on the other making fun of rationalists for something they’re famously super neurotic about is pretty funny, so it’s a complicated issue really there are good points on all sides

Postscript: More Testing!

After I posted this, the CEO of Equip came into my comments section and linked a post arguing against the Consumer Reports results for his products. I disagree with some of the content of his post but not with the main thrust. In particular, I disagree with his claim that cocoa “has naturally occurring lead and heavy metals like many fruits and vegetables.” This is a soil issue for cadmium and a post-harvest contamination issue for lead, as noted above. Nevertheless, he provided two certificates of analysis (COA) from Light Labs, which is a lab I’m not familiar with.

Assuming the COAs are correct, his product is fine and Consumer Reports’ results are extreme. The first COA is for unflavored protein. It shows low arsenic, low cadmium, low lead, and undetectable mercury. The second COA is for the chocolate protein variety, and it shows much higher arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury levels, presumably due to the cocoa. But, these levels are still generally regarded as acceptable, and they are less than what was detected by Consumer Reports, making this another case of discrepancy, both numerically and in interpretation.

As a final note on Equip, their CEO had the good idea to note what natural levels tend to be in a random vegetable. I think this is a really smart thing to bring up. He mentioned that “organic carrots test at 20ppb lead”, which compares to his chocolate protein powder’s 11.15 ppb. Like with protein powders, it is hard to get accurate figures on something like ‘the average carrot’, but I think he’s pretty close to correct for much of the world. This Polish study, for example, found 19.2 ppb lead in conventional and 11.8 ppb lead in organic carrots. But remember that this varies wildly by geography. In the FDA’s Total Diet Study (FY2018-20), Baby Food, Carrots had 7.3 ppb lead and raw baby carrots had no detectable lead at a 4 ppb threshold.

Note: this undersells contemporary European lead exposure, because Europeans have gotten fatter since 2017-18. It oversells European lead exposure at the time, because they were skinnier. Both of these biases are not very meaningful.

If we use 2010 EFSA figures with these 2017-18 weight figures, Europe looked far worse, but still didn’t seem like that bad a place.

something something betteridge's law of headlines tells me everything lol

I am an old fart and grew up with lead soldered copper plumbing and leaded gas as well as a full mouth of amalgam fillings. My wife is a health food fan and 'toxin' vigilante who had us doing hair tests for metal exposure. My teen son and I tested higher on lead when we were handling .22 ammo and reloading pistol rounds. Once we switched to nitrile gloves for handling rounds and loading magazines, the hair lead level dropped. I was far less worried about the issue than my wife, and even so the lead levels were not high. There is far too much fear about low levels of exposure. I live in an area with a close to the limit Arsenic exposure in the drinking water - natural background. I am not worried, my wife is. We do a lot of water filtration.