Laser Eye Surgery

Why I chose to do it, whether I expected it to work, and if it does

Here’s the complete timeline of my laser eye surgery:

I checked in at reception and was beckoned to an exam room where a nurse asked me to take some valium. I sat for about half an hour and, when it kicked in, they walked me to the operating room.

I sat down on the operating table, laid my head back, and I was given a plushie I was told to squeeze. Moments later, the surgeon brought a mechanical arm over my head.

A ring of white lights turned on and the surgeon administered some numbing eye drops. The surgeon inserted a speculum to keep my eyes open and then a green light turned on and I was told to stare at it. Eight seconds later, my right eye was done, the speculum was pulled off without feeling like anything, and we repeated the process on the left eye.

Surgery took about five minutes total, with under 20 seconds of laser time.

I felt like the surgery should have taken more time, but that was really it. I voiced my concern when I got up, but the nurse responded by telling me to look at the clock on the wall, and… Wow! It was clear. I guess it was done.

Laser eye surgery is a simple, highly-refined process at this point. It’s been done successfully for tens of millions of people globally. Given how many of these operations that have been done, we can be extremely confident that serious long-term complications from the various laser eye surgery procedures are exceedingly rare.1

The reason I chose to do laser eye surgery is three-fold: I recognize that the risks are low; I saw that the operation pays for itself in my case; and I’m aware that laser eye surgery works!

How Does It Work?

The operation I underwent is the safest, newest, and quickest, but I don’t want to start by describing it. Because so many of you won’t be eligible to undergo it, I want to talk about all but one of the options you have available, and I want to treat any recommendation to undergo them equivalently, since they are all safe and they are all effective.

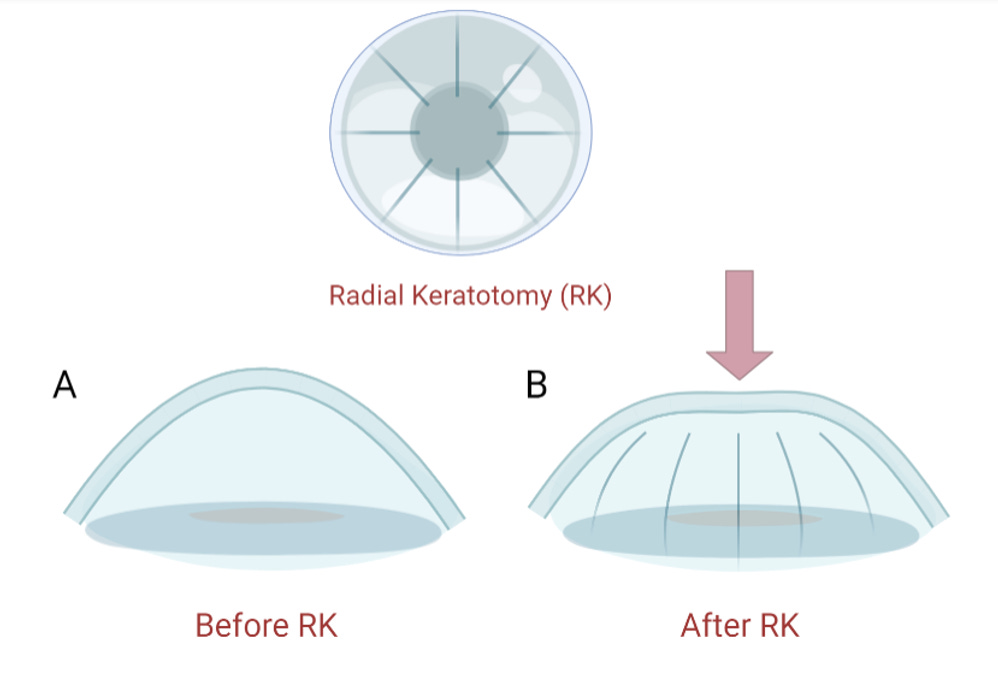

I’ll start with the oldest method that is still in use, albeit very rarely. This method is the only one I’ll discuss that is not almost-always safe and effective: radial keratotomy, or RK.

In RK, the doctor takes a diamond knife and cuts into your eyes to push down the cornea in cases of myopia (nearsightedness). This surgery is lengthy, it comes with an altogether too high—but still surprisingly low!—risk of infection, it hurts, and its results don’t last as well as the results of the other methods. Specifically, with time, the eye flattens out and people tend to be come hyperopic (farsighted).

I’m mentioning this for completeness, but please: just don’t consider this an option.

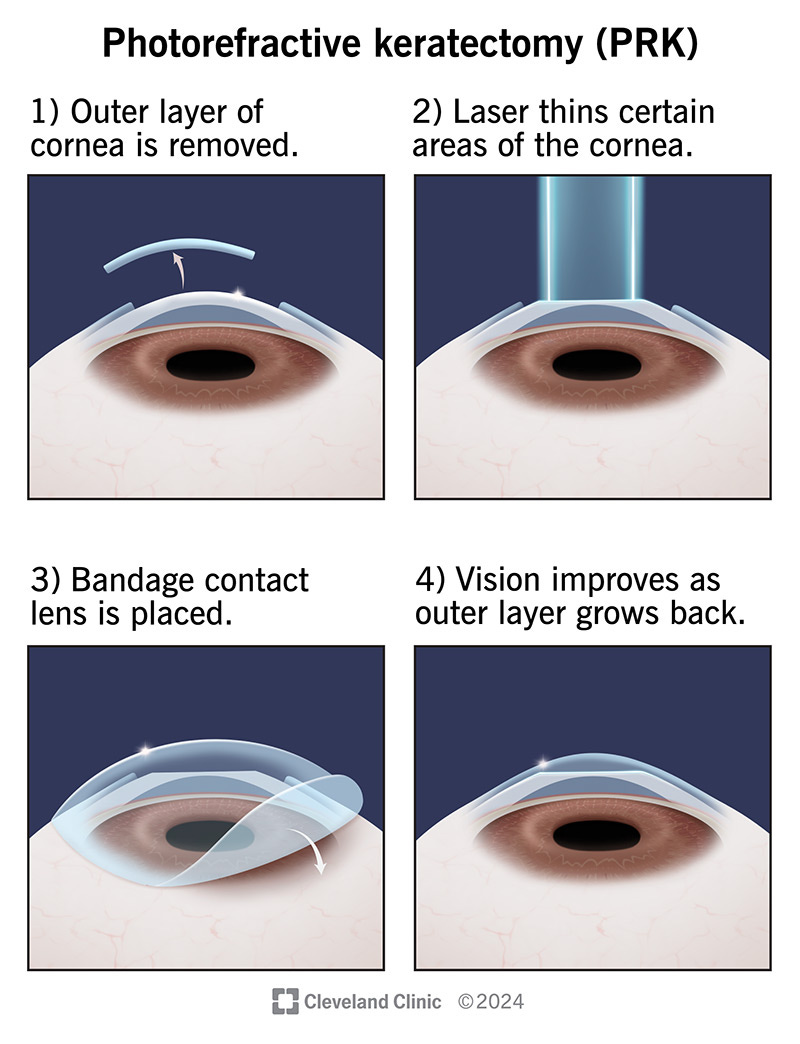

RK is up in the family tree from a more modern, effective, and safe therapy: photorefractive keratectomy, or PRK, the first therapy in the excimer laser era.

Excimer lasers are excited dimer lasers, and in laser eye surgery, they involve using argon fluoride gas to very precisely blast tissue with 193nm UVB. The laser destroys molecular bonds in tissue, breaking them down through a process called photoablation, which is ‘cold’, meaning that it prevents burning. This is used so that the cornea can be precisely sculpted without causing additional tissue damage.

In PRK, the doctor removes the surface epithelium from the eye and then they align an excimer laser to reshape the cornea to the desired shape. After that, the surface is bandaged up and the recovery period of about a month begins, over which time, proper vision starts to come back to the patient. The patient has the bandage removed around days 3-7 of recovery and during recovery, they’ll need to wear sunglasses outside, and avoid screens, driving, close reading, and physical activity.

During this procedure, patients are held under a laser, with numbing drops and a speculum in, for about 30-60 seconds. After the healing is done, patients can expect 20/20 vision and very high stability. In fact, a Navy pilot once ejected from a plane six months after PRK and nothing about his prescription changed.

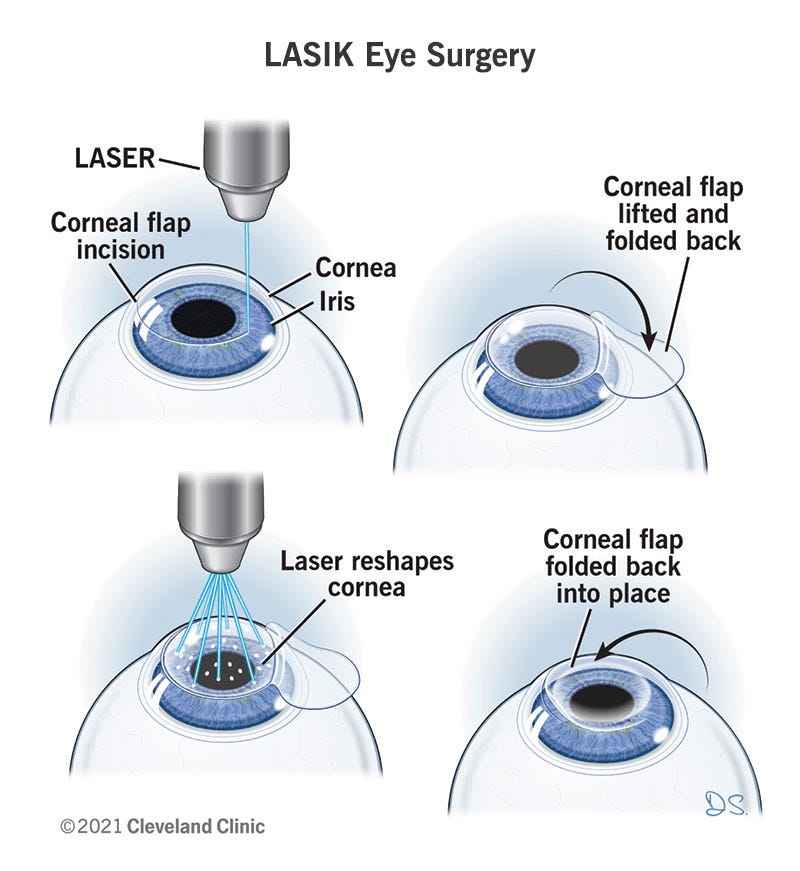

PRK was the first part of the excimer laser era, but not long after its introduction, laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis, or LASIK was introduced.

With early LASIK, surgeons would take a small, vibrating blade called a blade microkeratome to the patient’s eye to create a corneal flap that they would then lift, before performing the corneal reshaping with an excimer laser. After the corneas were reshaped, they would then set the flap back, keeping natural eye material behind, and allowing a faster recovery than with PRK. In fact, the recovery is so fast that patients usually report a ‘Wow’ moment immediately after surgery, when they discover that their vision has noticeably—if not fully—cleared up.

Over the following weeks, patients report their vision progressively improving and report that side effects like dry eye, halos, starbursts, and haziness tend to go away, leaving behind vision that, in the most modern version, tends to be around 20/15. That means that patients can often expect to see at 20 feet what a normal person sees at 15. At least 90% achieve at least 20/20, and some number are corrected to roughly 20/40, which still tends to be a large correction for those people.2

Before moving on, I wish to note that, nowadays, LASIK is generally not performed with a blade, but instead, with a femtosecond laser, for more consistent flap geometry, fewer mechanical flap edge cases, greater automation, and a faster procedure, among a handful of other benefits. Expect to spend about 30 seconds under a laser.

Not much later, a procedure blending PRK and LASIK, called laser-assisted epithelial keratomileusis, or LASEK, showed up. This procedure is basically a more advanced PRK with a faster recovery time, for patients with thin corneas. This procedure involves holding a sort of pan over the eye, filling it with alcohol, and scraping up a small epithelial flap with a surgical spatula. After doing this, an excimer laser is put to work fixing the shape of the cornea over the course of about 30 seconds to a few minutes, and the thin flap is then put back over the eye and covered with a bandage that’s removed a few days later, like in PRK. But, instead of a month of recovery as with PRK, the recovery time with LASEK is more like 3-7 days.

The flaps left behind by this procedure heal up extremely well and are basically unnoticeable without a lot of magnification. They can also be used years down the line for revisions, if needed. The flaps heal up so well that they can withstand airplane ejections, being shot with a paintball gun, being flicked with fingers, having the face struck by a tree branch, and so on. They are remarkably sturdy in both rabbits—the typical test animal—and humans. Furthermore, despite the existence of the flap, with the latest version of LASIK, habitual contact wearers might achieve lower rates of dry eye after recovery from the operation.

As time went on, the platform underlying both LASIK and LASEK became more advanced. The aforementioned laser flap creation was just part of this, but one of the more impressive additions was making the corneal ablations more individualized. This both improved the quality of LASIK results and increased the number of people who were eligible for the procedure while limiting the presence of side effects like halos and issues with corneal shape idiosyncrasies.

For older patients who have presbyopia—the age-related loss of the ability to focus on close objects—or slight hyperopia, conductive keratoplasty, or CK, came out around the same time some of these advances were happening. This procedure is uncommon because it’s generally considered inferior to laser-based techniques and there’s no subgroup of people for whom it’s really optimal. To do it, surgeons use a radiofrequency probe to tighten up areas of the cornea to make them more normal. This has a short recovery time, and is not a surgery that’s expected to have lasting results. Most patients only get 3-5 years out of this procedure, but they can seek out a revision if they want.

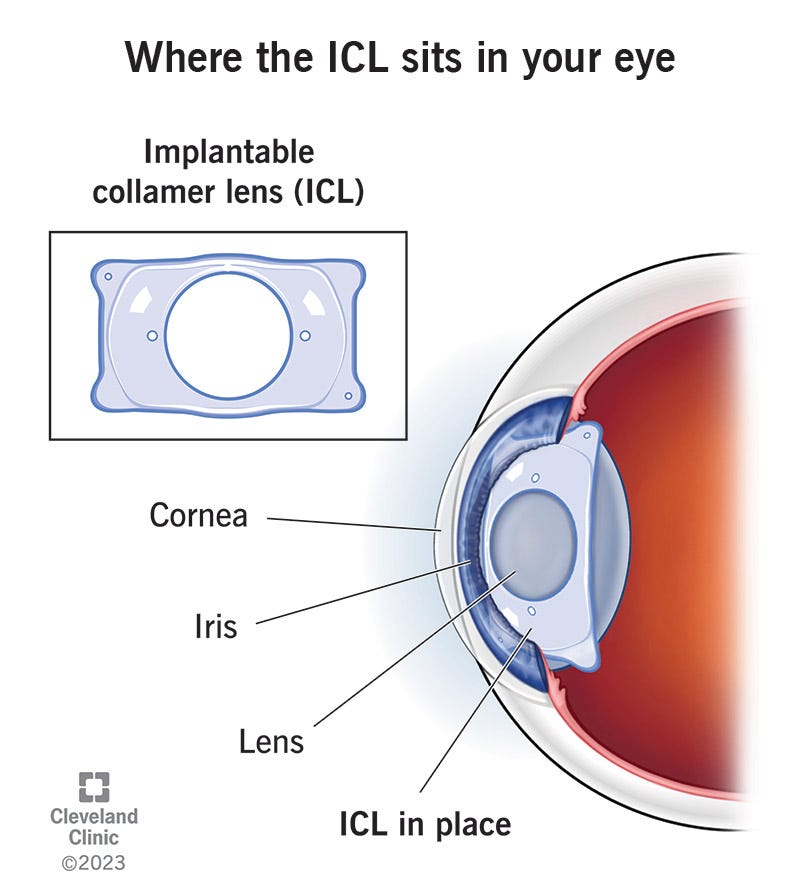

Some patients with particularly high prescriptions or thin corneas are ineligible for these procedures, and some of them can pursue implantable collamer lens, or ICL. With ICL, a small incision under local anesthetic is used to insert a custom lens between the iris and the eye’s crystalline lens. This is reversible, decently customizable, and has a short, one-day recovery period without an adjustment time like LASIK, while offering 20/20 vision and low risk of dry eye, via a roughly 20-30 minute surgery that patients often describe as daunting, but painless.

Refractive lens exchange, or RLE, is a similar procedure, and it’s kind of like elective cataract surgery. This is more appropriate for patients who are seeking to deal with presbyopia, so it’s suited to an older crowd that might not benefit as much from a laser-based procedure that’s primarily for treating myopia.

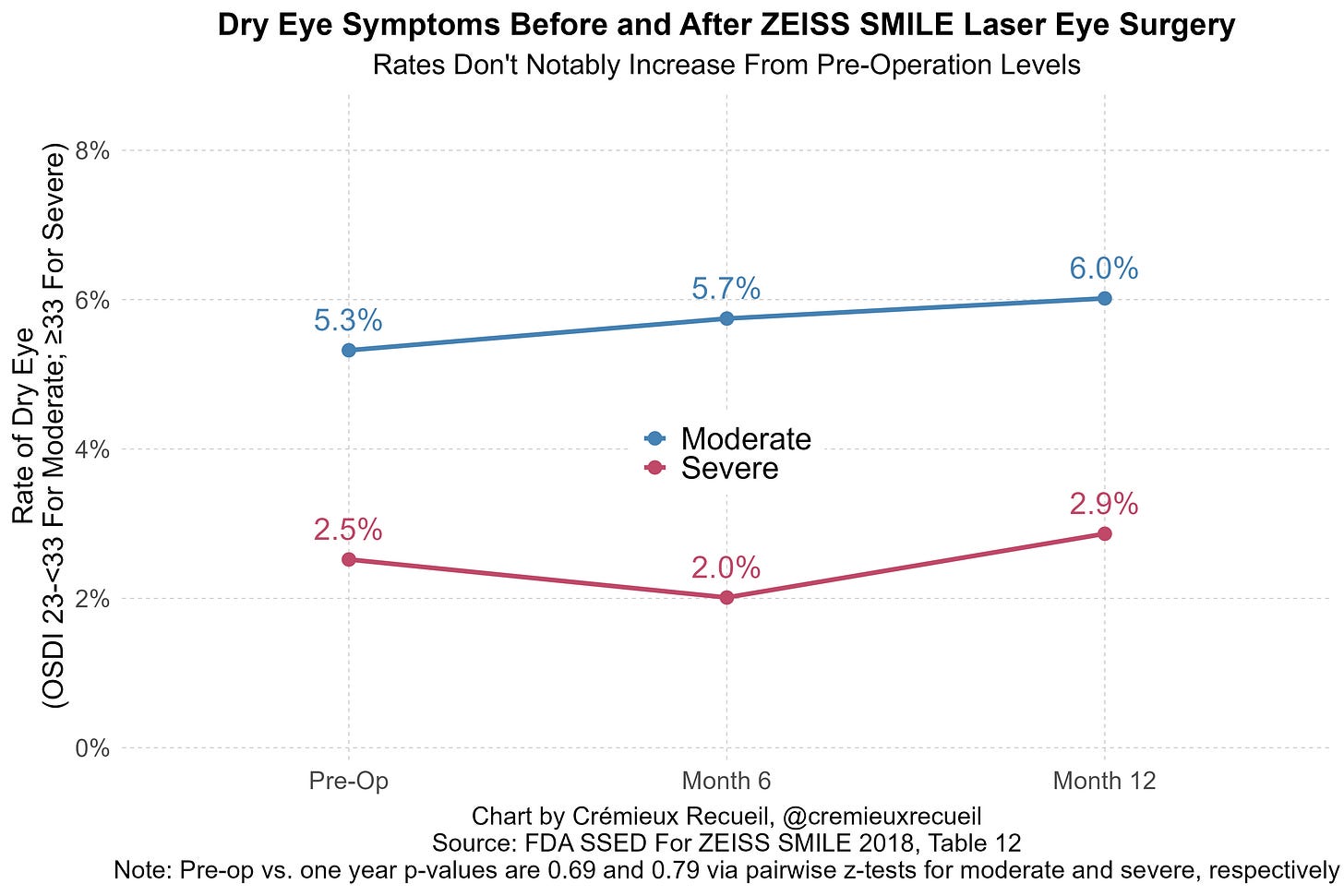

Finally—and this is what I elected to undergo—there’s small-incision lenticule extraction, or SMILE. This procedure involves using a femtosecond laser like the one used in modern LASIK, to turn part of your cornea into a disc called a lenticule, which is then sucked out through a tiny incision, leaving behind a correctly-shaped cornea with 20/20 vision, no flap, and the lowest risk of dry eye for the surgical procedures listed here. The only real downside is that the visual acuity is generally slightly worse than with the most up-to-date LASIK and there are fewer and more difficulty means of doing revisions down the line, if those prove necessary. But regarding the risk of dry eye, it’s so low that it’s hard to distinguish it from the pre-surgery rate!

The current state of the field is one where all of the popular procedures have massively improved with time, having been made more ergonomic and successful.

Which Procedure Do I Pick?

Ultimately, this is between you and your doctor. You state your desires and needs—what you want to correct, what you want to achieve, and what you’re willing to undergo—and after an evaluation, the doctor can match those preferences to whatever procedures are available to you, as a patient. You might be given the run of the gamut, or you might be limited to a few procedures like ICL and PRK, but this ultimately depends on your eyes, your wallet, and your comfort level.

As a general rule:

Young, mild-to-moderate myopia and astigmatism and in need of a fast recovery? SMILE or LASIK.

Have thin or irregular corneas? PRK, or sometimes ICL.

Have high myopia or a cornea that isn’t ideal for lasers? ICL.

Over ~45-50 and presbyopic and just want a one-and-done lens solution? RLE. But also, maybe a corneal laser plus reading glasses, or monovision surgery, where one eye is corrected for near and another for far vision, so as to create normal vision when viewed together.

Should You Undergo Laser Eye Surgery?

This is highly personal, but let’s go over some important factors.