Mensa: The Above Average IQ Society

What happens when people who obsess over tests form a club based on test results?

Mensa, the original high IQ society, has a well-earned reputation as an organization for nerds, a place where smart but not-quite-affable people go to reassure the world about their talents.1

Joining the society is easy, all you need is a qualifying test score showing you’re in the top 2% for smarts. A lot of people necessarily qualify, but Mensa’s membership hasn’t yet encompassed anywhere close to 2% of society.

Being a voluntary organization, there’s some self-selection into who joins up. It’s a group that has, unfortunately, become frequented by underachievers from modest backgrounds, with extensive interest in playing games that prove they’re intelligent but who have little achievement otherwise. For a lot of people, being in Mensa is a major part of their identity because it tells the world that they’re smart, even if they don’t show it in any other way.

This selection of high IQ oddballs has generated some peculiar research findings thanks to researchers who have investigated samples of Mensa members and treated them, simply, as high IQ samples. I won’t go into examples, but you can check some out here. The gist of this area of research is that higher IQs are related to better outcomes across the board, but when your ostensibly high IQ sample is composed of Mensa members, the group as a whole has a bunch of unusual traits like severe allergies, high neuroticism, poor mental health, etc.

This is well-trod ground by this point, but there’s another issue afoot: Mensa members are not actually smart.

Mensa members join the organization with a qualifying test result, but imagine if they had scored below the threshold. They obviously wouldn’t submit their results. But, results from tests are imperfect measurements, so Mensa member scores regress to the mean on retesting like everyone else’s. Because of this, many Mensa members near the qualification threshold should not actually be able to join the organization.

But that’s not all. Many Mensa members play games, and they play lots of them. Some even prepare for IQ testing, retake tests multiple times, etc. etc. and so on and so forth. They behave in ways that invalidate tests because they’re coming into test-taking with knowledge that most people shouldn’t be expected to have because they don’t waste their time playing games.

I was given data from a sample of more than 200 Mensa members who volunteered to take the Woodcock-Johnson III.2 223 of these people took the full test. The purpose of the original researcher’s investigation was to look at the ability profiles of Mensa members, a population they took for granted to just be a high IQ sample. But I have access to a much larger, population-representative sample of people who took the same test: the Woodcock-Johnson norming sample. Comparing the norming sample to this extreme sample can be a useful way to check a few things

How much regression to the mean matters for Mensa member’s IQ test results

How much tests are biased in favor of or against Mensa members3

Just how smart Mensa members really are

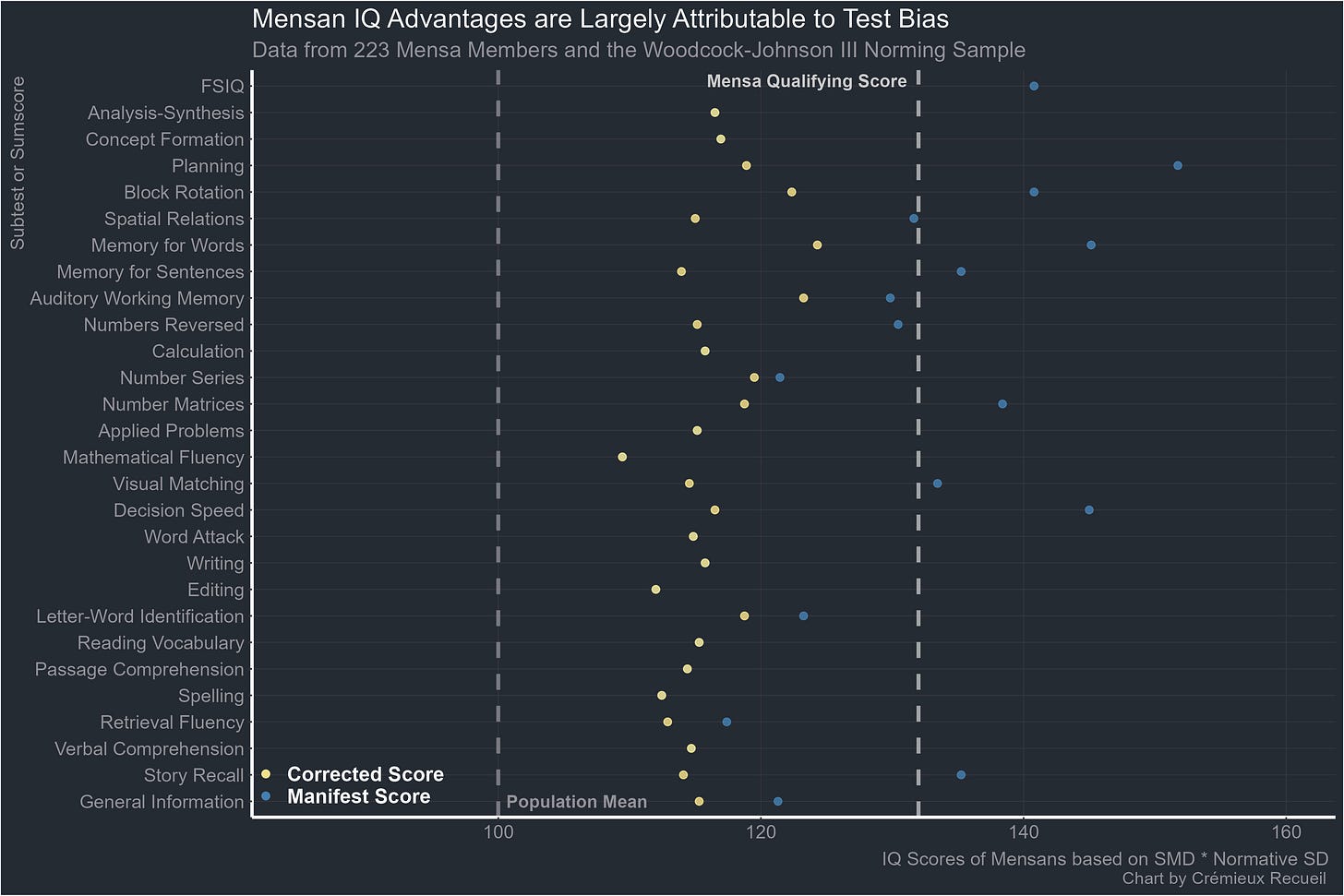

The answers were certainly interesting. To get to the common IQ metric, I took the gaps between Mensa members and the general population of adults (age 18+) and multiplied it by 15 and added 100. Take a look at how Mensa members test:

The blue dots are the manifest scores, which are the scores prior to any sort of correction.4 The yellow ones are the corrected ones or, in the cases where scores did not need any correction, they're also the manifest ones. In each case correction was needed because a partially invariant model was required, the bias favored Mensa members.

Mensa members had a full-scale IQ (FSIQ) of nearly 140, and that score was buoyed by a statistical phenomenon and a psychometric one. The statistical phenomenon is the composite score extremity effect, whereby imperfectly correlated parts lead to more extreme sums.5 This animation makes it clear how this works:

The psychometric phenomenon is test bias: tests are biased in favor of Mensa members because they practice at the content involved in the tests, or they’re otherwise more familiar with the content than a random person with the same level of intelligence should be. So, how smart are they? Let’s look at latent factors from a partially invariant higher-order model.6

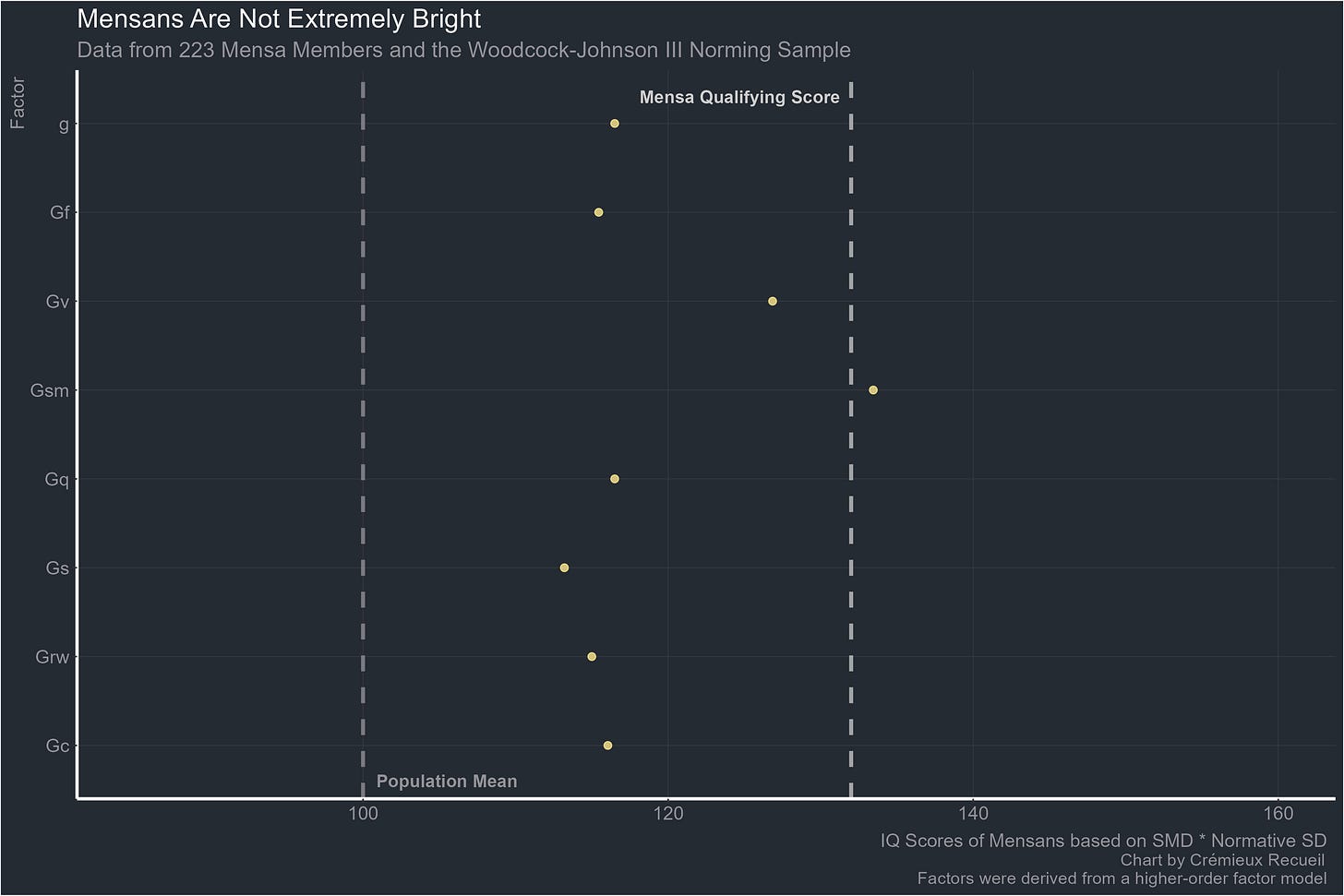

Mensa members have good memories and they seem to be good at visuospatial tasks, net of general intelligence. But, their general intelligence was actually only modest: their mean was equivalent to an IQ of about 117, a full norming sample standard deviation below the 132 ostensibly required to join Mensa.

To answer the question “Why do studies of Mensa members show poor outcomes despite high intelligence when the highly intelligent tend to do well in basically every way?” we now have two answers:

Mensa members are self-selected to be high-IQ losers.

Due to mismeasurement, Mensa members aren’t as smart as they believe they are.

Does being a Mensa member signal intelligence? Sure, but not high intelligence. And unfortunately, it probably signals being a weirdo who wastes their time playing games much more than it signals being someone smart.

As a disclaimer, I am a member of Mensa.

The people who volunteered to take the test — and were told they would be compensated in cash — may themselves be an unrepresentative sample, but this time, an unrepresentative sample of Mensa members rather than high IQ people.

With bias being removed by taking out the bias estimated with dMACS. The sign of the bias was figured out through computing dMACS_Signed.

The FSIQ scores were not corrected because the corrected numbers only apply to the means, and they’re computed at the individual subtest level. There is certainly some way to aggregate them, but I didn’t care to attempt that since I went on to look at latent gaps anyway.

This effect is all the more extreme for Mensa members because of Spearman’s Law of Diminishing Returns.

This is a model in which the only variables used to estimate factors are those that are unbiased between groups. An aligned model is one in which parameters are made as similar as possible when they’re close, but still significantly different, and that model produces similar results, albeit with slightly higher scores for Mensa members.

The level provided for g is more important for determining FSIQs than all of the group factors combined; the mean differences being in some cases comparable reflects a combination of Spearman’s Law of Diminishing Returns and higher performance in aspects of cognitive ability that explain small proportions of the total variance.

Because this is not the output from a bifactor model, the group factors do not contain variance from violations of local independence. With a bifactor model, factors tended to have limited residual variance if there’s not a lot of misfit to model out. The bifactor model for this battery fit poorly since g subsumed most group factors, so it couldn’t legitimately be fit for this comparison.

"Yes, I saw that he claims to be a member. I'm not sure if I buy it tbh. I don't know what the author is bitter about. It just reads like it's written by someone who was rejected by a mensan. The language is emotionally loaded and dismissive; it reeks of butthurt. Just my opinion btw" comment from MENSA subreddit. Maybe even stronger evidence than what you presented!

I'm not too suprised by this finding. In Mensa France for instance, they even have a page where you see a test sample composed of abstract item so that you can practice it, so to speak, and feel more confident before applying to Mensa membership. Just the fact they made it publicly available speaks so much about what they think of IQ validity.