No, Penises Haven't Gotten Longer

A case study in unbelievable results

If you know this man, chances are you have a very polarized opinion on him.

If you don’t, allow me to introduce him. Born 1894, the man pictured there is Dr. Alfred Charles Kinsey, the world’s founding sexologist and author of several of the field’s seminal texts. A man of fertile imagination whose mind was constantly pregnant with ideas, his work inspired thousands of researchers and carries on its atypically elongated lifespan to this day. A man of considerable courage, he published several long tomes on the topic of sex in a time when much of what he was doing was taboo. Over the course of his career he had the gall to study gall wasps; he had the balls to study balls; and he never shied away from sex with his colleagues.

It’s best not to focus on the man, so let’s instead discuss one of his interests: genitals. In his book Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948), he presented the results of extensive measurements of White male college student’s penises. His methods became typical for the field. But this is really rather unfortunate, since his methods were absurd. The description by Bogaert & Hershberger says it all:

In Kinsey’s original interview protocol, five measures of penis size were included: estimated erect penis length; measured flaccid penis length; measured erect penis length; measured flaccid penis circumference; and measured erect penis circumference. Penis length was estimated or measured along the top of the penis from the belly to the tip. For penis circumference, the men were told to measure at the point of maximum circumference. During the interviews, Kinsey and his colleagues often slowly slid a finger along a standard ruler with the numerals not visible and told the men to indicate when the length of their erect penis had been reached. For the measured sizes, the men were given specific instructions on how to measure their penises, and precision of measurement was stressed. These measures sizes were performed after the interview, and the participants mailed their measurements to the Kinsey Institute using standard response cards and preaddressed stamped envelopes. The Kinsey researchers recorded the sizes to the nearest quarter inch.

There’s something very important to note about this: people lie about the size of their penises. They lie, and they virtually always lie up. In the wider literature, there is a staggering difference in penis size between studies using methods like Kinsey’s and studies in which measurement is conducted by a researcher.

Kinsey’s study was one of the larger datapoints in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Belladelli et al. (2023). These authors had a fairly astounding conclusion: erect penis lengths have increased by 24% over the past three decades. At the same time, somehow the same was not true for flaccid lengths.

But, this meta-analysis was error-riddled, featuring omitted studies, unreliable adjustments, conflation of self-reports with objective measurements, the inclusion of samples of people with conditions that impact penis size, incorrectly reported sample sizes, measurements, ages, and so on.

In this post, I’ve gone through all of the studies and added studies that were omitted by the authors but should have been included. Details follow.

Methodological Notes

A lot of samples have to be excluded. You cannot run a meta-analysis for changes in penile length over time with samples of men seeking penile implants, men who think their penises are small, men with erectile dysfunction (and thus most urological patient samples unless explicitly noted otherwise), or men seeking — often hormonal, as androgen suppression — treatment for prostate cancer. Because these people are so odd with respect to the average, we have no idea if it would be appropriate to include them even if there were time-invariant numbers of them. But, there are not, so I am just going to exclude them entirely.

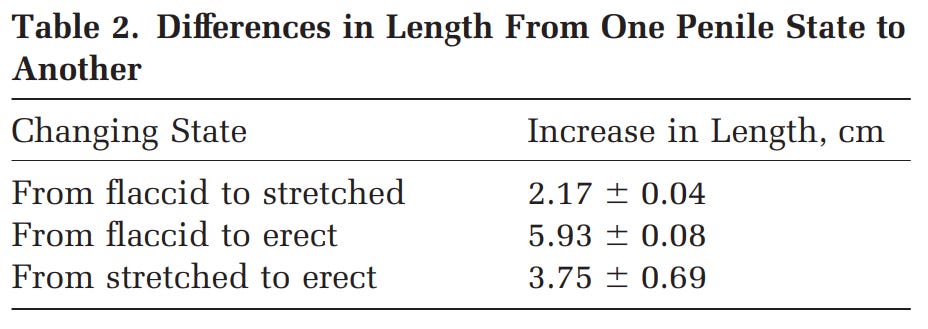

First, though some people believe stretched and erect penises are equal in length — but obviously not girth — this misconception is not supported by much data. It’s not even certain that stretched measurement is valid, since stretching tends to result in varying levels of arousal, confounding stretched with erect length, although similar complaints could be made about erect penises due to variation in erection quality and how erections were achieved (i.e., naturally versus injections). Moreover, stretching methods varied considerably in the literature. In some studies, stretching was just asking people to hold their penis out as far as they could firmly, while in others, it involved placing it in a device that held it with more force, with the effect being that it was usually closer to the erect length. Regardless, consider the work of Sengezer, Ozturk & Deveci (2002), who actually checked whether these two measurements were equal.

Second, men seeking penile lengthening procedures or men who think their penises are small are not simply deluded about the average size or their self-perceptions: they are at least somewhat correct and they do tend to have below-average penises. Mondaini et al. (2002) sought to disprove this notion by alleging that people who thought they had small penises really did just have more serious misperceptions. But in reality, their sample showed they have a distribution of penis sizes that was shifted to the smaller side, even if not significantly due to the small sample. Other samples support these sorts of men being smaller than average, so this isn’t concerning. More importantly, people who think they have small penises often have ED, which is much more robustly associated with smaller size. Plus, if we’re doing a meta-analysis, why would we use qualitatively different groups for the flaccid, stretched, and erect groups, as an analysis involving men who have ED must be? Using samples of these people is simply a way to confound results and introduce problems with time-varying sample compositions. Anyway, regarding ED, consider the data from Awwad et al. (2005):

Third, though the meta-analysis claimed to not use any self-report samples and to be comprehensive, both claims were clearly wrong: several samples were based on self-reports, like Kinsey’s (1948), as noted above, and many were excluded for no good reason. If we allow self-report studies like Kinsey (1948), we have to then include exact replications like Richters, Gerofi & Donovan (1995). But, self-report samples obviously cannot be used because people lie about their penis sizes. Lying is so pervasive that people lie about their heights in the same direction they lie about their penis size (bigger is better!). As an example of this, consider a study (see also) by one of the authors of a penis length study included here. This study showed height overestimation, and greater overestimation in bisexuals and homosexuals, coupled with lower objective but not self-reported heights.

Some studies included proper measurement and were not in the meta-analysis at all, and the authors should have known, since they were cited within studies they cited! For example, the studies Spyropoulos et al. (2002), Chaurasia & Singh (1974), Farkas (1971), Loeb (1899), and Awwad et al. (2004) were all cited within studies the meta-analysis cited, but they weren’t included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis clearly did not meet the goal of providing a comprehensive look at geographic or temporal variation, but I also don’t wish to claim that I have provided a comprehensive look either.

Fourth, there is a considerable literature on prostate cancer treatment effects on penis size, including studies about surgeries and hormones. For hormones, see Park et al. (2011) and Haliloglu, Baltaci & Yaman (2007). For surgeries, see Berookhim et al. (2013), Engel et al. (2011), Dalkin & Christopher (2007), Gontero et al. (2007), Perugia et al. (2005), Vasconcelos et al. (2012), Kadono et al. (2017), Su et al., 2021, Köhler et al. (2007), Savoie, Kim & Soloway (2003), Munding, Wessells & Dalkin (2001), and Fraiman, Lepor & McCullough (1999). For an example of both, see Brock et al. (2015). Because hormonal and radiation treatment are common in the run-up to surgery for various reasons (despite potentially not being useful; cf. Kadono et al., 2018), the baseline measurements from many of these studies cannot be taken for granted since they virtually all lack the relevant prior case history information needed to make the estimates interpretable as general population estimates. For all we know, prostate cancer treatment may have improved over time in such a way that penis size losses have become more minimal. Given how penis size loss is considered the “final indignity” of prostate cancer and a notable worry for many affected men, there’s clearly some reason for practitioners to have worked on this. Click some of those studies above to see evidence that the problem has been a topic of interest.

Since several of these studies were cited by the authors of the meta-analysis, it’s curious that they didn’t realize or even seem to care about their problems. But it’s more curious that, yet again, there were studies mentioned in the studies of prostate cancer sufferers that they cited that led to yet more work with penis measurements, and, if we consider prostate cancer patients to be usable for penile length measurements at all, they shouldn’t have been excluded, but mysteriously, that’s exactly what Belladelli et al. did.

All of this said, I hope readers don’t think the meta-analysis authors got everything besides these issues right. They didn’t: there are incorrect numbers in the meta-analysis for penile lengths, sample sizes, years, and ages. There was also evidence of arbitrary exclusions from certain studies. One study was also cited twice (Park et al., 2011) despite having only one available data point, so something else was presumably meant to be cited.

Regarding penile lengths, the errors were usually understandable, but readers wouldn’t notice because the authors of the meta-analysis didn’t provide their data. Readers would have had to look at their graphs and pull the data to know that the meta-analysis authors messed up in cases like with Shalaby et al. (2014). This study included the wrong measurement in the abstract (13.84cm) and the correct measurement in the body of the study (13.24cm), but the authors of the meta-analysis seem to have used the abstract’s errant number.

Regarding sample sizes, the errors were often harder to understand. For example, Tomova et al. (2010) was listed as having 310 people, but it actually had 310 per listed age, and the authors used ages 18-19, so the sample size should have been 620! But, because several studies used ages as young as 17, I don’t see why that age shouldn’t be included too, to bring the sample size up to 930. Alves Barboza et al. (2018) was more baffling, because those authors had a sample of 450, but the author’s proposed sample size for this study was double that for no apparent reason.

Regarding years and ages, the errors were usually less significant, but they could have been consequential in aggregate. For example, for year, Kinsey was cited incorrectly in their references and was listed with the citation year 1950 instead of the real year, 1948. Many studies were published several years after data collection, so this becomes a source of error because some studies are published closer to their data collection years. For age, studies with cadavers were not helpful since they didn’t list ages, and obviously cadavers tend to be older and thus stretchier for two reasons: age and death. But worse, other studies just had careless age number errors, like Söylemez et al. (2012), who reported a mean age of 21.1 (+/- 3.1) rather than the author’s reported 21.3. Needless to say, the conflation of age and cohort effects in this study was considerable and not able to be addressed due to the small number of studies. Known effects of age (i.e., greater penile elasticity, selection for normal samples related to lack of ED or prostate cancer) or location (geographic variation in size) simply had to be ignored for this reason.

Results for this reanalysis come from an inverse variance-weighed meta-analysis and study publication years are assumed to be accurate recapitulations of the year of measurement, even though that’s known to be wrong.

Trends in Penis Length

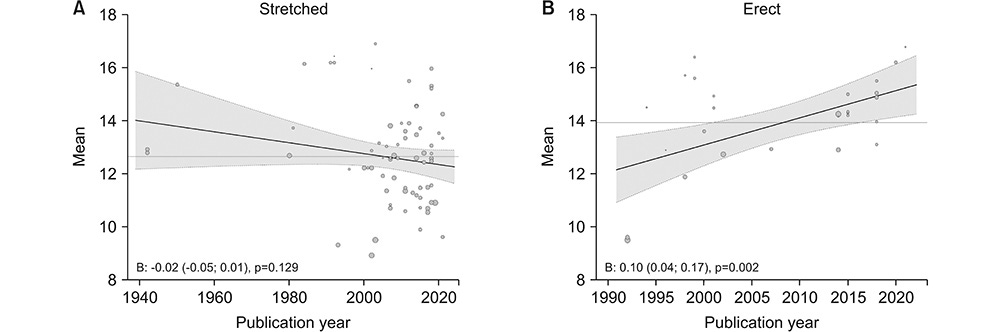

Belladelli et al.’s meta-analytic results by year were these:

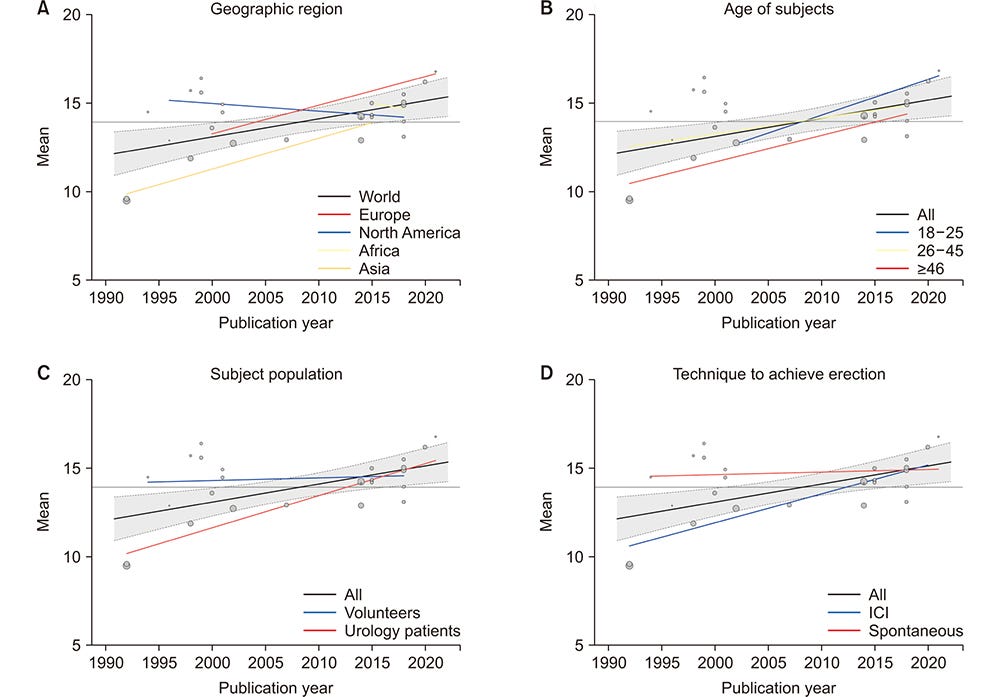

and they tested several moderators, despite there not being large enough samples for those to be anywhere near credible, and those results looked like this:

Taking these seriously, perhaps Asians and Europeans have grown much larger penises while North Americans have shrunken; drug-induced erections have gotten larger but natural ones have remained the same; volunteer samples (i.e., samples more likely to just be normal, healthy men) haven’t budged, but urology patients have gotten much larger. More interestingly, their erection trend (p = 0.04) was driven by the inclusion of a study of 20 Taiwanese men with erectile dysfunction who were given erections by injection. Belladelli et al. also improperly claimed this study had twice as many men (check their Table 1) as it did. Their erection trend was also apparently based on a nonexistent study conducted in the same year, because we see two dots in their plots, while the Taiwanese study was the only one with erection data in the year 1992 and their two other 1992 citations involved only flaccid and stretched measurements. Remove this study or even just correct the weight and they didn’t find any significant trends for erect, flaccid, or stretched flaccid length.

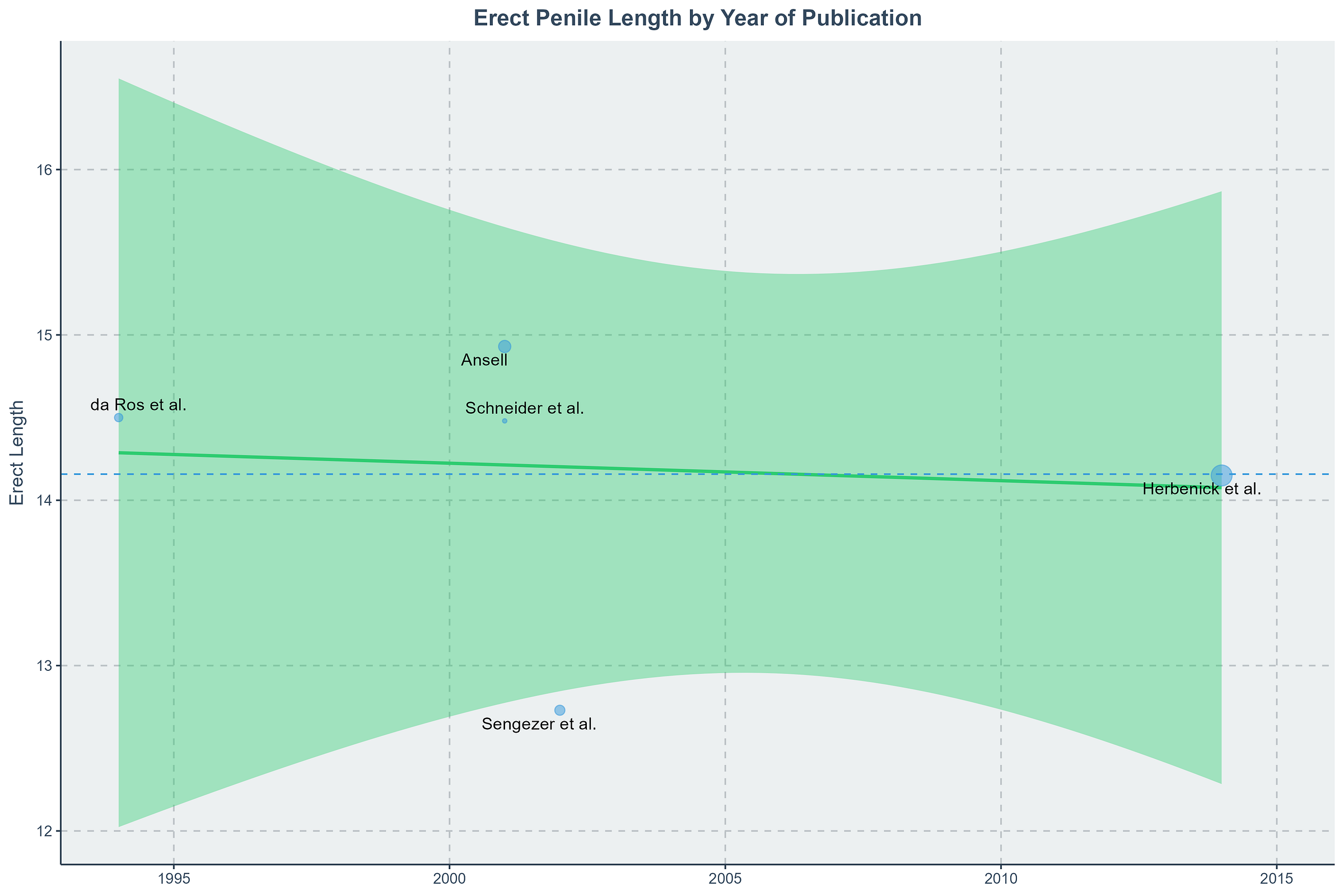

These were my results, where blue datapoints are ones included in Belladelli et al.’s meta-analysis and green dots are ones they should have been aware of but neglected to include:

Flaccid lengths didn’t change from 1899 to 2012.

Stretched lengths didn’t change from 1942 to 2018.

Erect lengths didn’t change from 1994 to 2014.

What About Girth?

A natural question is whether girths changed. There are not many datapoints for this. The total number of viable flaccid girth measurements was eleven while there were only five erect girth measurements. The correlation between flaccid girth and year was 0.18 (B = 0.0042, p = 0.597), and for erect girth it was a much greater but still nonsignificant 0.70 (0.0159, 0.192). The notably highly unreliable flaccid and erect girth means (SDs) were 9.04 (1) and 12.35 (1.08).

Am I Normal?

These numbers are not adjusted for geographic location, race, etc. because there’s too little data to reasonably do that. The average flaccid length was 8.74 cm (SD = 1.22), while the average stretched length was 12.76 cm (0.84), with an average erect length of 14.16 cm (2.45). Here are nomograms, so you can see just how normal you are.

I believe that the numbers for this nomogram are more trustworthy than those used by Veale et al. (2014) since they included several studies whose samples should be considered suspect, like studies of people seeking circumcision (usually phimosis sufferers, and thus people with slight deficits in length) or experiencing sexual dysfunction (see above). However, the numbers here were clearly more extreme in terms of both stretched and erect lengths. Their numbers were 9.16 (1.57) for flaccid length, 13.24 (1.89) for stretched length, and 13.12 (1.66) for erect length. Simply averaging my standard deviation estimates and theirs, noting considerable sample overlap, we get SDs of 1.395, 1.365, and 2.055, for a nomogram that looks a bit more likely.1

Here are the nomograms for girth, which Veale et al. proposed had flaccid and erect means of 9.31 (0.90) and 11.66 (1.10).

A Tentative Meta-Conclusion

Widely reported and counterintuitive studies should be considered wrong until extensively reviewed, and the peer review that precedes publication is virtually never extensive enough to provide the credibility a comprehensive post-publication review does. Peer review as typically construed simply does not provide any noticeable protective effect against the publication of nonsense and errors.

Belladelli et al.’s penile length meta-analysis produced a result that is almost certainly not true, and it should never have been taken for granted. Because of the absence of measurements conducted on samples that aren’t unusual over sometimes multiple decades, the ability to reliably discern a trend is also severely handicapped and any trends produced in newer studies will have to be unreliably computed based on differences from small numbers of past datapoints. So, don’t expect anything to do with changes in penis lengths any time soon.2

This is the nomogram based on the simple mean of this meta-analysis and Veale et al.’s.

Nomograms could be computed for testicular volumes too, but the data there is even more limited (K = 7) and highly inconsistently measured in a way that clearly impacts reported volumes. Nevertheless, the mean volume was 18.14 (2.29), with a correlation with year of 0.19 (0.0175, 0.681).

And if such work gets done over a long enough timespan, it will almost certainly not find a difference in trend between flaccid and erect penis lengths.

It might not be worth noting, but the current lack of trend is robust to treating measurement techniques (i.e., bone pressed versus non-bone pressed) differently, presumably because splitting the data or adjusting data points with fat pad data when available decreased the power for an already low power meta-analysis.