The Pro-Life Should Play a Different Game

Abortion opponents can succeed by harnessing trivial inconveniences

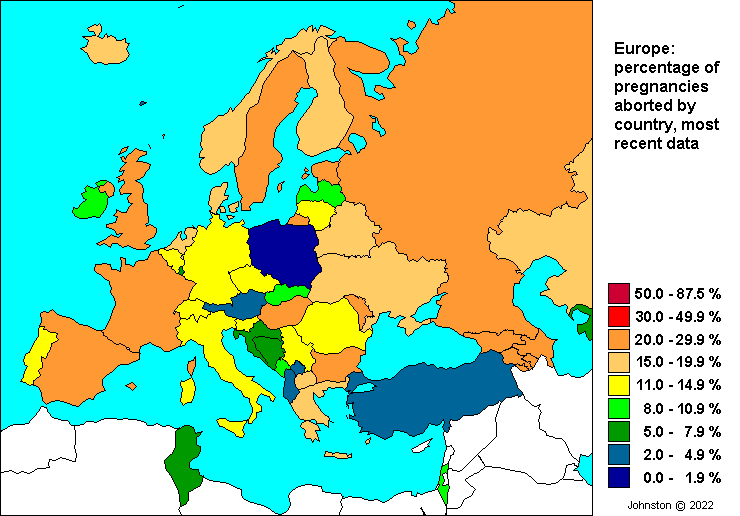

The valence of opposition to abortion in the United States is decidedly religious, but this isn’t the case in Russia. In fact, it’s not the case for much of the part of the world that was once behind the Iron Curtain. You can see this with your own eyes if you project abortion statistics on a map of Europe like so:

Within Europe, it’s clear that both Communism and Christianity have their roles to play. The role of the former in Russia is so extreme that abortion might as well be considered a first-choice for birth control.

Or at least, that’s how things were. In recent years, Russia has successfully reduced their abortion rate. By 2022, they’ve become much less of an outlier on the continent:

The most incredible thing about this transformation is that it doesn’t seem to have just been due to Putin’s much-publicized efforts to reduce abortion rates and accordingly boost fertility. There seems to be some similarity with the evolution of contraception usage and fertility rates in other places, like South Korea.

Putin’s efforts might not have actually done much at all. The more natural process of demographic transition and contraception adoption may have resulted in the abortion rate going down regardless of what he wanted to do. Something similar has occurred across the developed world, including in the United States:

The new received wisdom is that when affirmative action is on the ballot, Republicans win, while abortion is affirmative action for Democrats.

Most of the American public wants access to abortion, and they accurately feel that Republicans are a threat to that access. For this reason, it’s key to Republican electoral success that they avoid attempts to ban abortion through ballot initiatives. Republicans have come up with several workarounds, like six-week bans, but most of these efforts are transparent and enjoy the same unpopularity that outright efforts do.

Republicans will have more luck with a different strategy.

Easy Things Seem Hard

Trivial inconveniences are a major, underappreciated, part of everyday life.

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably already heard about the automatic opt-in pension nudge.

If you haven't, the gist is that automatically enrolling workers into making contributions to retirement plans greatly increases retirement plan contributions. This is no mere tautology, since people maintain the option to opt-out. Because of this combination of details, automatic opt-ins are a simple way to increase retirement preparedness without any threats to people’s financial freedom.

The success of this nudge reveals two things: the trivial action of opting in is a barrier to retirement contributions, and the trivial barrier of opting out is a simple way to keep people contributing to retirement funds.

Organizations weaponize triviality all the time, and you may not realize it. Here are a few examples:

High schoolers who want to drop out are often faced with the daunting task of having to sign a few pieces of paper. Forcing would-be dropouts to obtain parental permission and then have their parent officially withdraw them reduces dropout rates.

Some gyms keep their membership fees modest and make payments recurring. By making it a hassle to get rid of memberships, people continue paying even if they don’t keep going to the gym because they feel like it’s available, and that outweighs the effort to get out of their memberships.

Bars, amusement parks, and many other establishments have cover fees to obtain entry. Take notice of the change in attendance if you ever attend a free admissions day.

Companies will offer rebates on their products so they can make prices appear lower than they are. Since few customers claim their rebates because mailing them in is inconvenient, this works wonders for increasing sales without doing much to a company’s bottom line.

The power of trivial inconvenience generally declines with the personal importance of the thing it wards. As an extreme example, if you’re dying, you’re unlikely to avoid going to the hospital because you have to fill out the intake forms. But trivial inconvenience has lopsided effects. It is not so much a matter of life and death.

The Nontrivial Impact of Trivial Barriers to Abortion

This logic strongly applies to abortion, and many places have realized that.

For example, in Germany, if you want an abortion, you'll have to agree to counseling and waiting. Or in Israel, you have to have your abortion approved by a termination committee. In both cases, it's not exactly hard to get an abortion, you have to go through the process. Despite their simplicity and high approval rates, these things nevertheless help to keep the abortion rate down.

We know trivial inconvenience matters in America because of states like Texas.

In July, 2013, Texas passed House Bill 2, and immediately required two things:

Abortion providers had to obtain admitting privileges at hospitals within thirty miles of their facilities,

Abortion providers had to meet ambulatory surgical center standards, regardless of how they were doing abortions.

The bill also prohibited abortions after 20 weeks, required physicians to follow FDA protocols for medication-induced abortions, and restricted abortion pill use by requiring physicians to administer medication, with a limit of 49 days after fertilization.

Admitting privileges can take a long time to acquire, so when their requirement went into effect on November 1st, almost half of the abortion clinics in Texas closed shop. Due to a lawsuit, the ambulatory surgical center standards requirement went into effect on October 2nd, 2014, but it was blocked by the U.S. Supreme Court two weeks later so it never really did much.

In June 2016, the Supreme Court struck down these major provisions of HB2 and ruled that Texas had failed to demonstrate that they legitimately served to regulate women's health, while imposing a substantial burden on women's access to abortion. Thirteen months later, only three of the clinics that closed as a result of the admitting privileges requirement had managed to reopen.

This sort of supply-side abortion restriction had an effect, and it was a major one: access to abortion was made much more limited for millions of women.

A study by Lindo et al.1 analyzed the effect this had on abortion. It’s not hard to see how HB2 affected the accessibility of abortion services:

One single requirement backed up by the power of slow bureaucracy managed to halve the number of abortion clinics operating in Texas. This halving brought a doubling in both the distance the average person had to travel to get to an abortion clinic and the number of people each clinic would have to service.

So how did people respond? Well, by having fewer abortions of course.

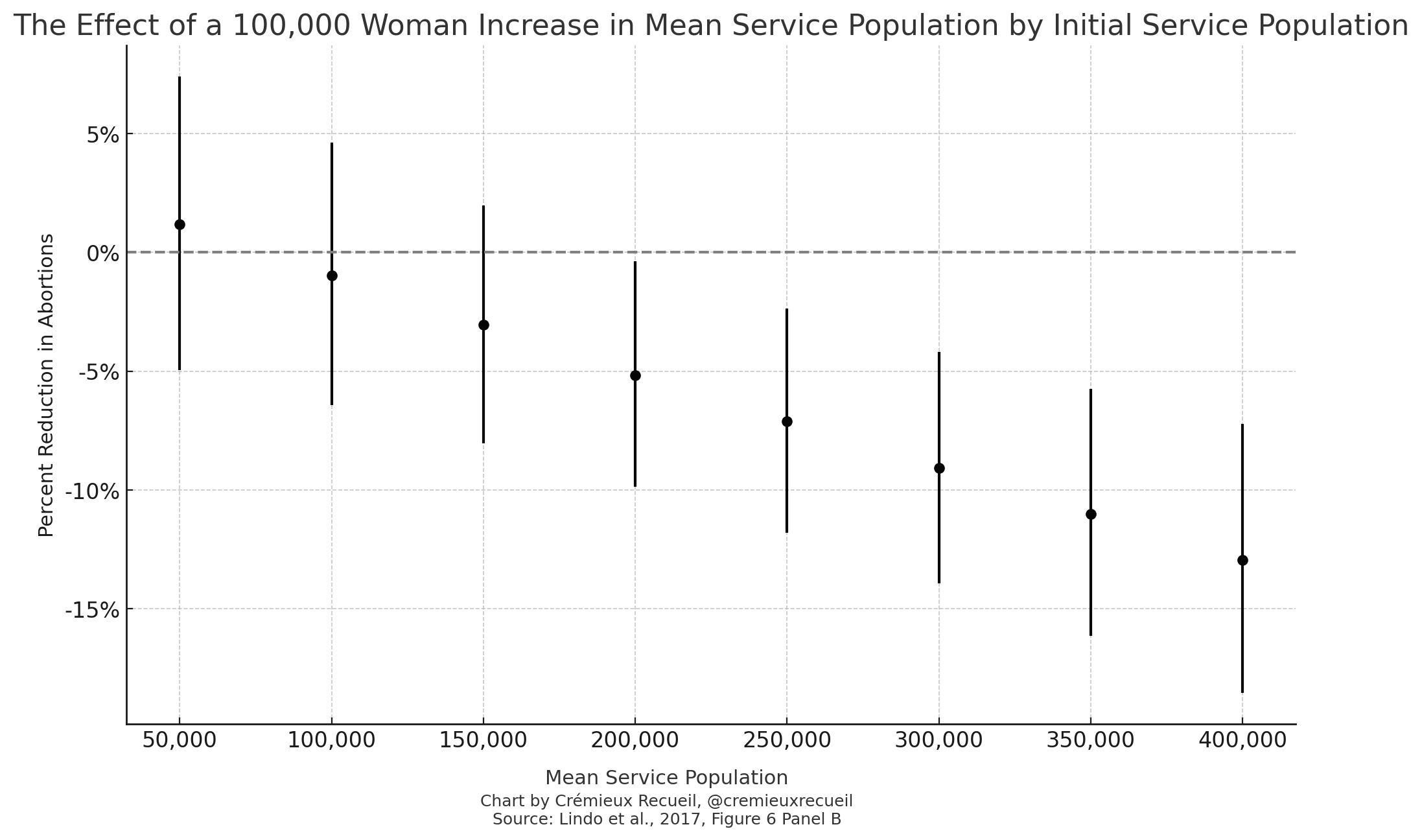

Nontrivially, when the population a clinic had to service increased, they became less capable of offering people abortions. Trivially, when people ran into longer wait times, higher costs, or both, they gave up on getting abortions. You can see this in the following graph that shows the effect of adding 100,000 people to a clinic’s service population on the number of abortions they performed.

Shockingly, the largest clinics took the biggest hits, indicating that the capacity to expand was either not available, or was limited in some way, like through HB2’s regulations.

This may seem off because surely clinics would not provide fewer abortions if their clientele expanded abruptly, they would just provide at least the same number and as many additional abortions as possible. But the number of abortions they provided did decrease because clinics became congested. Congestion leads to fewer abortions because clinics cannot deal with the volume; it also leads to delays, because clinics have to give people later appointments. Accordingly, the gestational age of abortions increases with greater congestion, and this points to yet another way congestion reduces abortions: by pushing people over the deadline, giving people time that leads them to rethink and give up on seeking an abortion, and by creating more opportunities for appointments to be missed for reasons that have to do with later-term maternal mobility problems.

A more shocking and explicit way to see the impact of trivial inconvenience is to look at how much abortions declined for people within a given distance of a clinic.

If a person had an abortion clinic nearby, a 25-mile increase in the distance to the nearest clinic reduced their probability of obtaining an abortion by nearly 10%.2 But on the other hand, for people for whom an abortion clinic was already more than 200 miles away, an additional 25 miles didn’t matter. For them, obtaining an abortion was already an inconvenience, so another 25 miles didn’t matter.

Being 10% less likely to obtain an abortion because the clinic is a mere 25 miles away is a staggering effect. It’s hard to imagine 25 miles of driving being worth raising a child all the way through to adulthood. It’s almost unbelievable, but this magnitude of effect has held up in a subsequent synthetic control study that also looked at Texas, a difference-in-difference study that used data from Wisconsin, and a national-level difference-in-difference study as well.

It’s only natural to ask what happened to birth rates. Surely, if people couldn’t abort, they would have more kids, right? Lindo et al. estimated the effect on births and they estimated what would have happened if, hypothetically, all of the “missing abortions” induced by access restrictions since 2012 showed up two quarters later.3 This theoretical result contrasts sharply with the empirical one:

If a person’s nearest clinic went from within zero to fifty miles to fifty to 100 miles away, Lindo et al. projected that birth rates would have increased by 2.1%. They projected that if their nearest clinic went from zero to fifty miles away to 200 plus, then birth rates should have risen by 3.6%. But alas, there were no significant effects on birth rates for any distance. The most plausible increase in birth rates was, shockingly, for the smallest increase in distance.4

So what happened?

A few things, but generally-speaking, people had a broad behavioral response to reduced abortion access: they changed how they acted so that they would require fewer abortions.5 That means that, instead of seeking abortions, people were using contraception, improving how they used contraception, illicitly inducing abortions, using other means to avoid conception, or just having less sex.

One of the available tests of this is comparing Hispanics and non-Hispanics. The reason this tells us about substitution away from clinical abortion to other methods of contraception or abortion is simple: Hispanic women could easily go to Mexico to obtain Cytotec, the brand name version of Misoprostol and an over-the-counter drug just south of the border.

In the first trimester, Misoprostol causes an abortion for nine out of ten pregnancies by inducing uterine contractions. Its efficacy drops as pregnancy progresses and it can also increase the risk of birth defects if it fails. But since this drugs works well and it’s well-known, access to it should increase the effect of a nearby clinic closure for Hispanic women. And indeed it does! If the nearest clinic goes from zero to 25 miles away for Hispanic women, abortion rates decline by 11% if they’re near the border; if they’re far away from the border, however, the abortion rate only declines by 3%.

Speaking of race and ethnicity, I recommend checking the paper’s preprint Figure D2. In it, we see something curious: the aforementioned larger effects for Hispanic women are there for both congestion and distance, but at the same time, there’s only one effect size for Black women. For black women, distance and congestion didn’t matter; their abortion rates simply declined by 4% for distance changes and 7 to 10% for congestion changes, without any significant moderation across levels of either variable. The effect of trivial inconvenience only applied to White and Hispanic women, but despite that, there were no consistent effects on births by race.6

Lessons for People Who Care About Abortion

This feels like it has a lesson for everybody.

Family values conservatives may not succeed in raising birth rates by much in the short-term or at all in the long-term if they manage to ban abortion. When Texas seriously restricted abortion access, abortion rates declined, but fertility didn’t significantly budge because people changed their fertility-related behaviors in a way that offset their newly-limited ability to receive an abortion. The national-level difference-in-difference study I mentioned did have more power to detect a change in births and it used an increase of 100 miles instead of 25 miles, so it found a larger effect. That study found something that may be heartening in sign and disheartening in magnitude for family values conservatives:

In a scenario in which a full set of 25 forecasted bans take effect, abortion rates are predicted to decline by an average of 25.0% in ban states. Aggregating to the national level, abortions are predicted to fall by 8.5% (or about 79,000) in the first year following enforcement of the full set of bans. Births are predicted to increase by 1.5%, suggesting that about three-quarters of the women seeking abortions who are trapped by increases in distance give birth as a result.

For pro-choice people, it’s important to know that this is a strategy many Republicans understand. They’ve acted on it many times, and it has worked to reduce abortion rates. They get confused and let the hardcore push them for stronger ends that are less popular and more likely to fail, but some of the more sensible ones still know that supply-side abortion restrictions are on the menu and they work. Even if they fail to move the needle on births, they still make people’s lives harder. It’s not hard to imagine a world where part of the behavioral adjustment people resort to is just reducing the amount of sex they have, making everyone more miserable!

It’s important to remember this, on both sides, because supply-side abortion restrictions are much easier to sell than wholesale bans. All you have to do is swap up the questions that go with the bill. For example, “If they’re so interested in women’s health, shouldn’t abortion clinics be ready for anything that might happen? Vote to bring abortion clinics up to surgical center standards.” The public does not think in terms of second-order effects without coaching, so bringing abortion clinics up to a particular standard puts the onus on those clinics and the costs might be too much for them to bear, causing them to shut down. That’s a win that pro-life people can sell the public.

Realize that this is always the game and you can promote or better ward off the implementation of supply-side restrictions.

The lesson for the hardcore who can’t stomach a single abortion by any means is that they need to give up and moderate. This isn’t a lesson that I made clear in this post, but it is true. Wholesale bans do not sell. They are not popular enough for the public to accept them, and poorly-disguised bans won’t work out in the moderate-to-long term because they’re always simple enough that people will be able to wise up.

If abortion access can still be qualified, weaponized inconvenience is a restricting way to do it. The hardcore will have to accept that it’s better to have one dead baby than ten, and work from there. The best way to prevent that last one is also already known: they have to work to change the culture around fertility and abortion. I don’t know how to go about that, but it’s a battle pro-life people must win if they want to end abortion in a world where a wholesale ban isn’t yet an option.

I primarily reference the preprint throughout this piece, although for the results I note, the paper is not different. For clarity, Section F in the paper is 4.6 in the preprint and the paper’s Table 4 is not in the preprint. Some graphs from the preprint are also not contained in the paper. Here’s a link to the paper’s supplement.

A less powerful study that was also from Texas found a similar effect in the opposite direction, for violent offenses. In that study, a 25-mile increase in clinic distance was estimated to increase the number of violent offenses by up to 1.9%, with smaller impacts at greater initial clinic distances and with smaller lagged effects.

The standard errors for the theoretical estimates were borrowed from the empirical ones.

The last graph might be interpreted to mean this is not shocking. That is not the case because their estimand differ.

The aforementioned synthetic control paper provided weak, but suggestive evidence that this behavioral change was not facilitated by increased retail purchases of condoms and emergency contraception. That study also suggested there was a small but significant effect on the birth rate.

Distance might have increased White births and left Hispanic and Black ones unaffected. Congestion may have increased Hispanic births without increasing the rest. Some, and perhaps most, of the heterogeneity in these effects may reflect modest statistical power.

There was perhaps one other notable effect on birth rates (Table 4), and it might be an upside: the aggregate effect was a null because of a nonsignificant reduction in first births accompanied by a significant increase in second births. If a person is having their nth birth and n isn’t 1, that means they’re already a parent. The people who had more kids were people who already had parenting experience. Perhaps that meant the kids that resulted from increasing limitations on abortion access were had by more capable parents! But to put some rain on this, the increase may have been among people who were less capable parents, but nevertheless had kids, as many do. We can see this because the increase was observed among unmarried mothers rather than married ones. This one isn’t clear.

Each of the three other cited studies did find an effect on births. Because of the dubiousness of synthetic control studies and how it used the same identifying variation as the main study I discuss with less power, I’ll consider that one suggestive and not discuss it. The Wisconsin study suggested that a 100-mile increase in clinic distance translated to 30.7% fewer abortions and 3.2% more births. This is a larger shift than the 25-mile increase discussed in Lindo et al., so it makes sense it would be an apparently larger effect. The national-level study by Myers reported Lindo et al.’s effect was a 25.8% decline in abortions with a zero-to-100 mile shift in Texas and she reported the Wisconsin result was a 24.9% decline for the same distance. In Myers’ national-level data, the effect of the same shift in distance was a decrease of 19.4% for the first 100 miles and 12.8% for the next 100 miles. In Myers’ study, abortion reductions mechanically translated to a 2.2% increase in births for the first 100-mile increase and 1.6% for the next. As noted in the last section, Myers was able to make the projection that, in a post-Roe world where abortions fell by 25% in “ban states”, national-level abortion numbers would decline by 8.5% in the first year following enforcement, while births would increase by 1.5%. In other words, three-quarters of the women trapped by distance will give birth, so there is an effect of abortion reductions on births, but it is modest at best.

Myers’ results should be qualified by her limitations, which make her study quite different from Lindo et al.’s. In Lindo et al.’s study, they were able to assess the impact of congestion and to provide evidence of an increase in self-managed abortions for Hispanics, who had more opportunities to do them. Myers was aware of these issues but had no means to account for them. Since congestion was responsible for more than half (59%) of the effect in Lindo et al., that’s potentially very meaningful. On the other end of things, the Wisconsin study failed to find a congestion effect, but, their decrease in abortion clinics was smaller than the one in Texas and the law in Wisconsin required multiple physician visits, which augmented the distance effect by approximately 1.33 times. Myers also noted more factors that might limit the effective decline in abortion and effects on the birth rate, like the setup of organizations that provide financial and logistical support to women seeking abortions in affected states, facilities that open up in non-ban states on the borders of ban states, and the rise of self-managed abortions, like the aforementioned Cytotec abortions.

What I ultimately believe is that in the immediate period following a ban, many more would-be abortions will turn into births than will, proportionally, in the longer run, where people will have more time and ability to plan around bans and trivial inconveniences and adjust their behaviors accordingly.

Thoughts on this? https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/09/07/us/abortion-data-bans-laws.html

The goal of pro-life shouldn't be to minimize abortions. The safest way to do that would be to minimize births, which is the opposite of what pro-life wants.

The problem I have with pro-choice people isn't necessarily that they get abortions, but that they are low fertility and just don't seem to like children and big families all that much. If your average pro-choice person had four kids and aborted one Down syndrome kid along the way that would be fine, but in reality pro-life people are averaging at least an extra kid per woman over pro-choice people. I think peoples view on abortion is basically just a proxy for their views on what kind of status family and children should have.

Pro-life should focus on making people want to have kids, and thus they will voluntarily get fewer abortions. And while it would "be more expensive" in the short run those incentives have to include the middle and upper middle class because its really them we need to have more kids. They may not get abortions, but they are birth controlling themselves into sub replacement TFR.