Tim Walz's Good Idea

Free lunches are real and probably good

Imagine what a midwestern school principal looks like. Focus enough and you’ll probably imagine someone like Tim Walz, the current governor of Minnesota, a former educator, and a potential vice presidential pick for Kamala Harris’ 2024 run.

Tim doesn’t seem like a very impressive pick for vice president. He has a relatively high (~50-60%) approval rating in his state, but he doesn’t pull in many voters outside of the Twin Cities, he hasn’t really been a policy innovator, and he doesn’t have much charisma. But, perhaps because of the drama surrounding Josh Shapiro of late, Tim Walz has now taken the top spot on Polymarket’s list of potential vice presidential nominees. Regardless, Walz has been a proponent of one policy that I’m excited to see him champion as his national brand recognition grows: free lunches.

[Edit: Tim Walz was selected as the VP nominee.]

[Edit: He lost.]

As of 2019, the cost of school meals in the U.S. was about $21 billion dollars, of which roughly a quarter was paid by the fees gathered from students and their parents. Thanks to COVID, as of 2022, only $0.7 billion of that $21 billion check was paid by students and the rest was covered by public subsidies. Altogether, the cost of school lunches (and breakfasts) is not much to the government, and covering universal free school lunches wouldn’t be too bad for the public purse.

Universal free school lunches might also pass a cost-benefit sniff test. There are papers arguing that free school lunches serve a social purpose, with claimed effects like:

Reduced delinquency

Boosted test scores

Curbed food insecurity

Improved student health

Reduced rates of child abuse

Reduced stress and worry for parents and children alike

I don’t put much stock in the results for delinquency, test scores, or child abuse, and the student health effects seem wrong in light of the concomitant general finding of increased student BMIs, but none of that is relevant. It’s easy to like free school lunches because they could pass the cost-benefit test through their effects on grocery prices.

[Edit: A new meta-analysis has come out. It confirmed my suspicion: none of the effects on student outcomes held up.]

Family Grocery Spending

Per the Census’ Annual Social and Economic Supplements, there were 62,515,000 American families with children under age 18 in 2023. 35,495,000 of those kids were between ages 6 and 18, and 18,971,000 were between ages 6 and 12.

If we assume the USDA’s moderate cost grocery budget accurately approximates median American household spending, then families with a child aged 6-18 spend about $330 per month, per child. Let’s assume the median American family has two kids and two parents, and the father eats the USDA’s $376.90 monthly figure while the mother eats $317.70. That means the median family spends $330 * 2 + $376.90 + 317.70 = $1354.60 per month on groceries.

If we use the 35,495,000 of those families with kids between ages 6 and 18, that nets out to $48,081,527,000 in monthly spending. Just using the kids between ages 6 and 12, the monthly food spending nets out to $25,698,116,600. If we round and halve these numbers to be conservative and to feel more realistic (given plenty of sources report monthly grocery spending between $300 and $1,300—all over the place!), we get about $24 billion and $13 billion in spending per month from these families.

The Retail Response to School Lunches

Two recent papers have estimated the effect of the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) on local food prices. Briefly, the CEP is a program that makes school lunches free to every kid in a district where at least 40% of the children are eligible for free school lunches. That includes a lot of children already, but it also means that there’s time-varying exposure to free school lunches within districts, because eligibility varies, and also because states rolled out the CEP at different points in time.

Marcus and Yewell (MY) used changes in CEP eligibility across states for their causal identification. Before getting to their results, I want to show their map of each zip code’s percent CEP eligibility:

More poverty, more program penetrance, exactly as we should expect. That’s a good start!

Now, the design used by MY was an event study, with results stratified at the household level. The impact of CEP rollout in an area was to reduce the household food purchases for families with kids by about $20 after two years:

These savings were not solely driven by the sorts of food provided as a result of CEP (i.e., lunch and breakfast foods), indicating that households substituted away from food purchases as schools moved towards them. In this sample, the impact amounts to a reduction in lunch and breakfast food spending on the order of 8.6%, and of total food spending of about 5.2%, so this sample seems to have somewhat lower grocery expenditures than samples like the families in the latest Household Pulse Survey. This sample is a bit older than the latest Household Pulse data, but I still doubt inflation could explain a discrepancy on the order of, say, a thousand dollars. In any case, what we see in these results is a reduction in household spending that’s beyond the cost of the program to these households due to their tax incidence. If the reduction is just $20 dollars per household with a kid aged 6 to 18 per month, that’s $8.52 billion in savings versus a program whose total cost is $21 billion, so among this group, the savings are already substantial parts of the way towards covering the program.

The authors’ findings didn’t stop there. They also found that the USDA-based health ratings of the food families opted to purchase after CEP rolled out in their areas were unchanged—in other words, the ratio of unhealthy to healthy food at home neither increased nor decreased as a result of the advent of free school lunches. Even more interestingly, all of these results held up for families that were and families that were not previously eligible for free and reduced-cost school lunches. What’s more, measures of food insecurity and parental statements that they “ran short of money, tried to make food or food money go further” also declined. In short, CEP reduced budgetary constraints on households without any apparent negative impacts.

To be sure, MY’s results might mask some downsides of CEP, but what those are isn’t clear. Given that the households that are most impacted by CEP at home are poor ones, I would argue that kids’ nutrition probably improved in aggregate, because even if the government screws up school lunch healthfulness, they would probably do better than what those parents would have provided.

The second study was Handbury and Moshary’s (HM) independent investigation of the impacts of the CEP’s grocery impacts, not just with household expenditure reporting, but additionally with data from retailers. The CEP impact on household expenditures looks like the impact observed by MY, but here it amounts to a sizable reduction in household grocery spending and also in the number of grocery trips by households with kids, but not those without them:

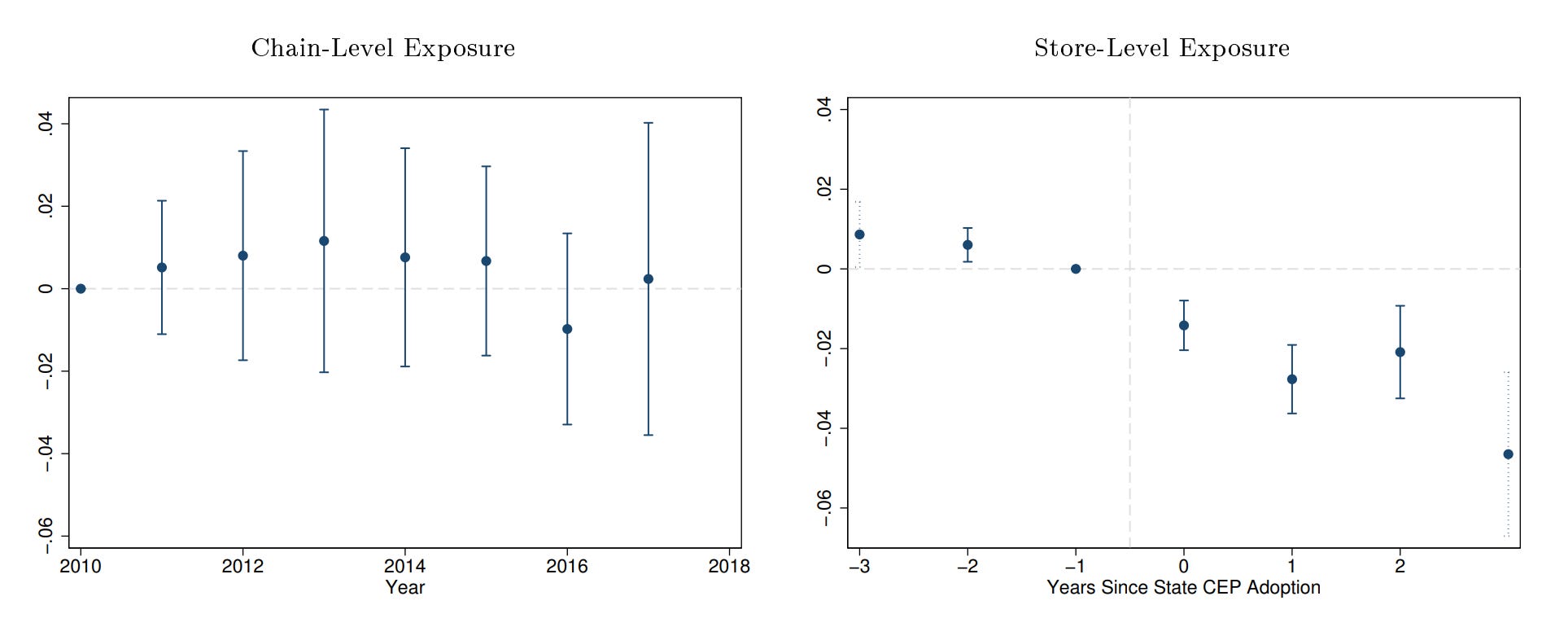

The retailer response to this reduction in spending at their stores is the novel detail from this study. HM found that, rather than locally lowering prices at the most affected stores, retailers lower prices across whole chains, reducing prices somewhat for everyone, generating indirect benefits that appear outside of CEP-affected areas! The chain-store disparity in effects is remarkable:

But even though prices go down across chains, revenue does not, because the stores lowering their prices see compensatory purchasing. On the other hand, the CEP-affected stores do see a reduction in revenue!

Now isn’t that interesting? The CEP losers are the local grocery stores, but the grocery store chains as a whole aren’t harmed thanks to consumer responses to the diffuse price effect of CEP that happen because chains usually use uniform prices and they end up responding to their aggregate rather than local CEP exposure.

HM estimated the welfare impacts of CEP as being substantially positive and not relegated to families alone.

Free School Lunches As Family-Oriented Redistribution

These studies didn’t estimate the effect of universal free school lunches, but instead, a partial impact of free school lunch availability. They understate the benefits for that and several other reasons I’ll get to in a second.

First, if CEP reduces the median American family with children under age 18’s grocery spending by just 1% per year, that could be $2.88 billion saved by families, or $1.56 billion if we just count those with children aged 6 to 12. If the CEP saves the high estimate of 10% of the median family’s grocery bill, it might save families more than its total cost. Through the diffuse effects on prices, it might save childless families meaningful amounts too. The savings to American consumers could easily come to equal the costs of simply making school lunches universal, and that’s before considering any other benefits of providing them.

Because the distributional impact of this program is obviously to give to families directly and—less obviously—through grocery price savings, it’s also a good example of pro-family policy. The redistribution is not just to families, but to those that are doing the worst, since they’re disproportionately positively affected by school taking the pressure off of their household budgets.

This policy redistributes to families across income strata, making it acceptable to conservatives,1 and it redistributes progressively, making it acceptable to liberals. Win-win. The speculative benefits might make this a win-win-win, too.

By helping families with their budgetary constraints, the incidence of child abuse might be reduced, and children may come to school less stressed not only because they’re eating better, but also because their home environments are less stressful. This route could impact test scores, but more probably, it could impact homework completion, since a better home environment for homework completion is entailed. Homework completion might also be impacted by free breakfasts incentivizing arriving at school, either by bus, by walk, or by parental transport, and giving kids relatively focused time that could be spent on homework.

In addition to speculative benefits on student behavior, parental interactions, test scores, GPAs, health, food insecurity, and whatever else, free school lunches might also just be efficient. If everyone is automatically eligible, then the infrastructure required to means test children could be disappeared, and that infrastructure is expensive. The cost of means-testing infrastructure has unfortunately not been itemized for the U.S. as a whole, but it’s not hard to imagine it running into the millions, and it is accentuated by the costs school districts currently pay to contract with third party payment processors.

Means-testing is also a policy that disparately impacts families with unintelligent parents. Huge numbers of people are eligible for free or reduced-cost school lunches and they don’t receive them because means-testing can be hard to deal with. Tim Walz might be able to attest to this, because in his state of Minnesota, participation in the program ended up being 20% higher than expected, because lots of people participated who weren’t expected to. Those people could be under-utilizers, but they might also just be parents who are doing fine who are taking advantage of the newly available opportunity to simplify the experience of sending their kids to school. A mix of both is probably true and either way is fine.

That’s my case. To sum it up, free school lunches (and, to reiterate, breakfasts):

Don’t cost the government much

Are already heavily subsidized, so going universal won’t boost costs much

Redistribute to families

Redistribute to the poor

Generate sizable consumer benefits via grocery price effects

These increase the impacts for families

These can benefit childless households in some ways too

These don’t hurt grocery chains

Cut expensive means-testing bureaucracy

Cut out the need for school districts to interface with payment processors

Save parents cognitive effort and time spent contending with Byzantine educational bureaucracies

Might reduce food insecurity

Might benefit students in diverse ways, from potentially reducing child abuse rates to improving classroom focus and giving kids more focused time in school to do their homework and additional reasons to attend in the first place

So Tim, spread the message, because you could be the champion for a government program with a ratio of benefits to costs >1.

Caveat: ‘some’, of course.

One issue with universal free school lunches here in Sweden in recent years has been that it is incredibly easy for schools to reduce the lunch budget if they ever struggle financially. This is because each small successive cut is barely noticed and the main group who suffer can't exactly go anywhere else.

So school lunches get continuously worse nutritionally (schools will most likely excuse this with the environmental impact) and then it begins to defeat the purpose of the project itself.

Free school lunch removes responsibility from parents, placing it with government. It encourages a mindset of dependence on government. It is not “pro-family.”