Two Stories About Jews

When anti-Semitic propaganda backfires; and answering the question, does love win?

I like reading about history. Sometimes I’ll make a Twitter/X thread on some historical topic of interest. Below, I’ve decided to describe two historical anecdotes about Jews that I consider pretty amusing.

The first story is provided for free and the second is for subscribers.

Europe and Japan Perceive Propaganda Differently

Before the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-05, there was a globally-widespread belief in something akin to “White Supremacy” in combat, where White nations like Germany, the British Empire, and the United States were seen as undefeatable in combat.

To be sure, there were multiple instances of Whites losing in combat to non-Whites prior to the Russo-Japanese War. For example, the Zulu repelled the first wave of the British invasion in the Anglo-Zulu War, but they ultimately ended up decisively defeated when the second wave happened. A similar outcome was reached in the Anglo-Ashanti Wars, with the British taking making limited headway between 1823 and 1874, but decisively crushing the Ashanti in the period 1895-1900.

The First Italo-Ethiopian War is another example of a European power being, in a sense, trounced by a non-European one, but this deserves qualification. Critically, the First Italo-Ethiopian War was an Italian loss, where Italy ended up forced to concede after losing a fight in which its forces were outnumbered by at least four-to-one. But the concessions Italy was forced to make in the Treaty of Addis Ababa were minimal. They merely had to recognize Ethiopia’s independence, but they otherwise maintained their Eritrean possessions. This loss did serve as a powerful symbol for Pan-Africanism, and a proof that Africans could win against European powers, but it wasn’t a lasting symbol, and the victory was viewed as one with limited meaning because, after all, Italy was not a Great Power. Similarly, the poor prestige of Spain and Portugal, and the perception that the rebellions led against them were ones led by other Whites limited the degree to which their losses were perceived as a crack in the edifice of White world supremacy.

The difference with Japan was one of magnitude: Ethiopians weren’t cattle to be pushed around, but Japan was a capable, first-rate and, indeed, Great Power. After the Japanese victory, no one could doubt that it was possible for a non-White nation to meet Whites in direct combat, with their forces fully-mustered, and win. But don’t take me at my word alone; this was also the judgment of the arch-White Supremacist Lothrop Stoddard, who wrote the following in his 1920 book The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy:

The bitter resentment of white predominance and exclusiveness awakened in many colored breasts is typified by the following lines penned by a brown man, a British-educated Afghan, shortly before the European War [referring to World War I]. Inveighing against our “racial prejudice, that cowardly, wretched caste-mark of the European and the American the world over,” he exultantly predicts a “coming struggle between Asia, all Asia, against Europe and America. You are heaping up material for a Jihad, a Pan-Islam, a Pan-Asia Holy War, a gigantic day of reckoning, an invasion of a new Attila and Tamerlane—who will use rifles and bullets, instead of lances and spears. You are deaf by the voice of reason and fairness, and so you must be taught with the whirring swish of the sword when it is red.” [Quoting Aclimet Abdullah in “Seen Through Mohammedan Spectacles,” in Forum, October 1914"]

Of course in these statements there is nothing either exceptional or novel. The colored races never welcomed white predominance and were always restive under white control. Down to the close of the nineteenth century, however, they generally accepted white hegemony as a disagreeable but inevitable fact. For four hundred years the white man had added continent to continent in his imperial progress, equipped with resistless sea-power and armed with a mechanical superiority that crushed down all local efforts at resistance. In time, therefore, the colored races accorded to white supremacy a fatalistic acquiescence, and, though never loved, the white man was usually respected and universally feared.

During the closing decades of the nineteenth century, to be sure, premonitory signs of a change in attitude began to appear. The yellow and brown races, at least, stirred by the very impact of Western ideas, measured the white man with a more critical eye and commenced to wonder whether his superiority was due to anything more than a fortuitous combination of circumstances which might be altered by efforts of their own. Japan put this theory to the test by going sedulously to the white man’s school. The upshot was the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, an event the momentous character of which is even now not fully appreciated. Of course, that war was merely the sign-manual of a whole nexus of forces making for a revivified Asia. But it dramatized and clarified ideas which had been germinating half-unconsciously in millions of colored minds, and both Asia and Africa thrilled with joy and hope. Above all, the legend of white invincibility lay, a fallen idol, in the dust. Nevertheless, though freed from imaginary terrors, the colored world accurately gauged the white man’s practical strength and appreciated the magnitude of the task involved in overthrowing white supremacy. That supremacy was no longer acquiesced in as inevitable and hopes of ultimate successes were confidently entertained, but the process was usually conceived as a slow and difficult one. Fear of white power and respect for white civilization thus remained potent restraining factors.

To understand the difference from the petty skirmishes the British had with the Ashanti and Zulu, or even the relative meagerness of the First Italo-Ethiopian War, simply look at the broad military details of the conflict between Russia and Japan:

The war began with a Japanese surprise attack on the Russians in Port Arthur, China (modern-day Lüshunkou in Dalian, Liaoning) in February, 1904.

Throughout the war, the Russians faced logistical difficulties that made it difficult to meet their Japanese foes effectively. To make matters worse for Russia, the Japanese fleet had the advantage of proximity and novelty: their ships were newer and faster, and they made heavy use of radio communication, allowing them to outmaneuver the considerably larger Russian fleet every step of the way.

Nearly a year after the war began, the Russians and Japanese faced off at the Battle of Tsushima. The Russian Baltic Fleet suffered more than 5,000 casualties, 800 injuries, and nearly 6,000 of its sailors were captured. For the Russians, this was an unimaginably poor showing. since all they had to show for it was 117 deaths and 583 injuries inflicted on the Japanese. After all was said and done, the Baltic Fleet lost the majority of its warships, putting Russia in the position of having practically no naval forces left in the region.

The Russians were forced to sue for peace and the Japanese were officially recognized as the victors with the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth in September of 1905.

As an interesting historical anecdote, the mediator of this treaty was then-president Theodore Roosevelt. For his efforts in making this peace, he became the first American to win a Nobel Prize: the Nobel Peace Prize of 1906. The announcement of this peace prize acted included a further acknowledgement of what everyone now knew: a non-European nation had joined the ranks of the world’s Great Powers. The official reason cited for Roosevelt’s award was “his role in bringing to an end the bloody war recently waged between two of the world's great powers, Japan and Russia.”1 The emphasis there is mine; the importance is yours to decipher.

An interesting detail of this war was that Japan probably would have lost were it not for the efforts of a single American banker.

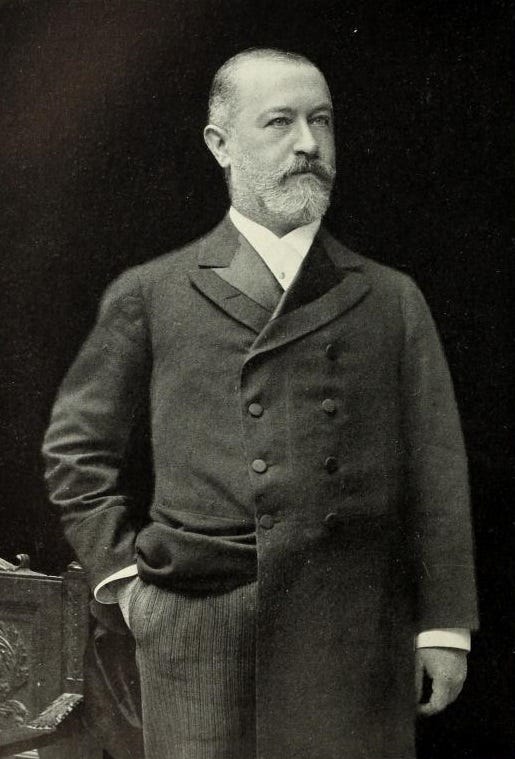

Jacob Schiff was an important proponent of American railroads and he ran numerous major corporations, like Wells Fargo, Union Pacific, and Equitable Life Assurance. He was also Jewish.

Schiff's advocacy on the part of Jews was renowned. He actively fought to combat anti-Semitism at home and abroad and he bankrolled numerous Zionist efforts. As one might imagine, he felt deeply about Jewish problems.

One such problem that drew particular ire from him was the April 1903 Kishinev Pogrom, in which 49 Jews were killed, 92 were gravely injured, and more than 500 suffered other injuries, including the destruction of more than 1,500 homes.

It's only natural to ask what incited the pogrom. The answer delivered by Count Arthur Cassini, the Russian ambassador to the U.S., was that it wasn't anti-Semitism. No, in his own words, "The situation in Russia, so far as the Jews are concerned is just this: It is the peasant against the money lender, and not the Russians against the Jews. There is no feeling against the Jew in Russia because of religion. It is as I have said—the Jew ruins the peasants, with the result that conflicts occur when the latter have lost all their worldly possessions and have nothing to live upon."

Or in other words, Jews were being scapegoated for other people’s economic woes. In Kishinev (modern-day Chișinău, Moldova) itself, there's evidence that public officials also cooperated with the rioters, enabling this tragedy.

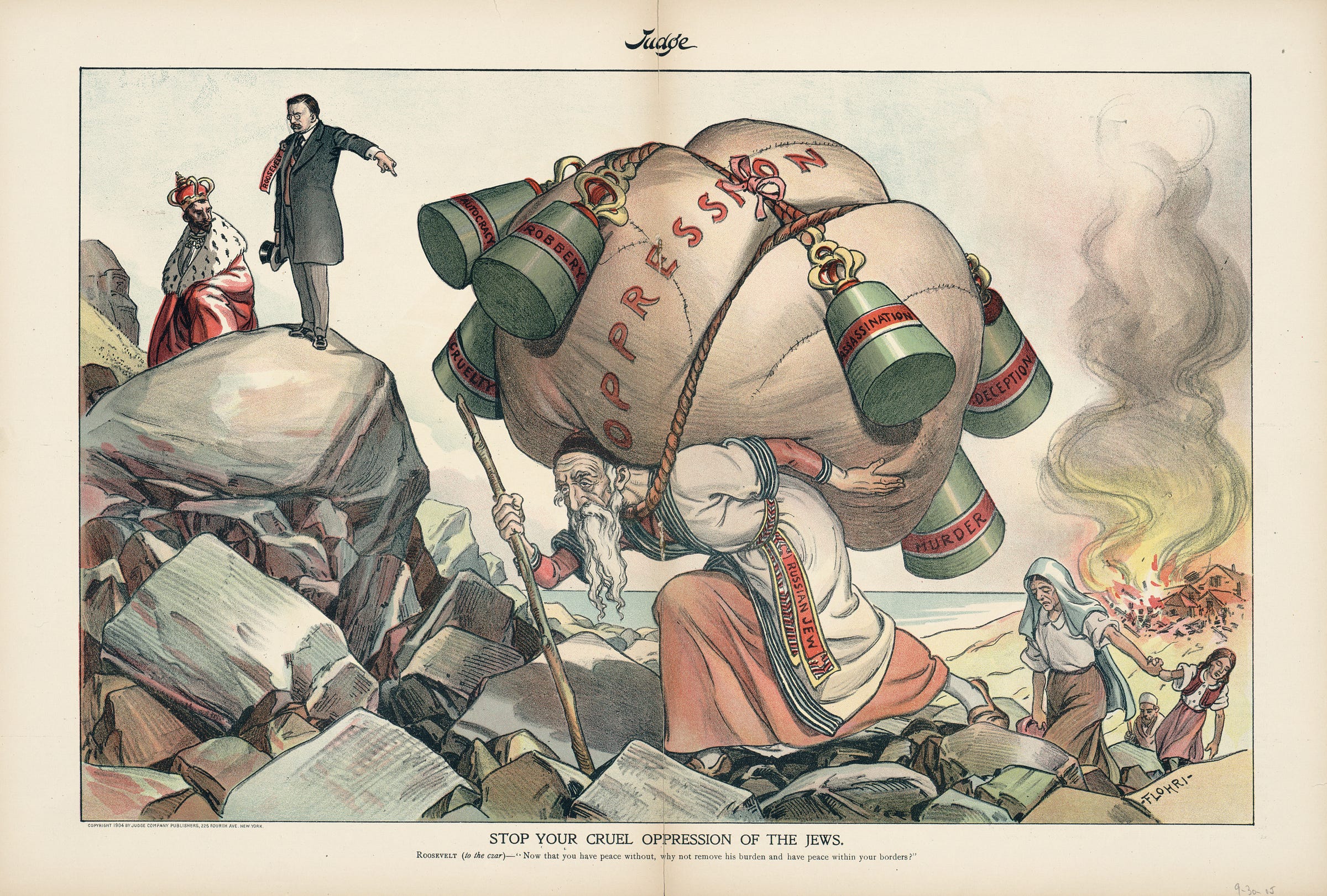

William Randolph Hearst brought the media's focus on the pogrom and dispatched journalists to investigate immediately. Thanks to his efforts, two instigators were sentenced to imprisonment and millions heard about what happened. Comics depicting the American view towards the plight of the Jews of the Russian Empire graced the newsstands. Here’s an example:

The effect this pogrom had on Jews was immediate and extreme. The outcry from American Jewry was incredible, and it resulted in huge amounts of aid being funneled to the tens of thousands of Russian Jews who wanted to escape from the anti-Semitic persecution that the Czar didn’t seem willing to stop. This particular pogrom was also the motivation behind Theodor Herzl's proposed "Uganda Scheme" to obtain Jews a measure of security against the burgeoning anti-Semitism in Europe by resettling them in Africa.

Schiff had developed a hatred for Russia due to this event and several other incidents, so when he saw the Japanese and Russians engaging one another, he offered his help. And help he did!

Schiff floated $200 million in bonds to provide Japan with the modern equivalent of more than $7 billion in war backing. This was equal to about half of Japan's total expenditures during the war and, accordingly, when Japan won, Schiff was lauded by the Japanese. He would go on to receive the Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure and the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star from the Emperor Meiji himself.

The irony of Schiff’s involvement is that it made anti-Semitism worse. A recently-published forgery entitled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion felt as though it was confirmed through Schiff’s military support. To many, the credibility of The Protocols was now strongly affirmed. In his fight against anti-Semitism, Schiff had become all the proof anti-Semites ever needed for the conspiracies they believed in.

But as is often the case, backfiring is rarely a simple matter. In this instance, Schiff’s efforts might have backfired on the propaganda front, but that is precisely why there is one Japanese man listed as hasidei ummot ha’olam: Righteous Among the Nations.

The honorific Righteous Among the Nations refers to those who altruistically risked it all to save Jews from extermination in the Holocaust. The title has been conferred to more than 7,000 Poles, nearly 6,000 Dutchmen, almost 4,000 Frenchmen, and more than a thousand others, with the notable inclusion of some five Americans, three Peruvians, two Chinese people, one Egyptian, one Irishman, and one Chiune Sugihara, the vice-consul for the Japanese Empire in Lithuania.

Chiune Sugihara has been the subject of a considerable amount of media within Japan, and when a book on his life emerged in the English-speaking world, it immediately invited a lawsuit in Japan. The book, entitled In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust, came out in 1996 and in it, there’s an honest attempt to describe the life and deeds of this diplomat. But Chiune’s widow engaged in a lawsuit against the book’s author, Hillel Levine, over his depiction of Chiune. The lawsuit appears to have been a frivolous attempt to secure exclusive movie rights, and I can’t find what the result was, so I’ll choose to simply take the depiction of Chiune in Levine’s book as accurate.

Sugihara had evidently come to hold the same set of beliefs about Jews that the Japanese military officers Koreshige Inuzuka and Norihiro Yasue, as well as industrialist Yoshisuke Aikawa had: they believed that The Protocols were not only true, but vindicated by Schiff’s efforts, and that they presented a clear suggestion that Japan would greatly benefit from inviting Jews to settle in its imperial possessions.

This belief went so far in Japan, that Inuzuka and Yasue had managed to convince the Foreign Ministry of Japan that each embassy and consulate the world over should keep the ministry informed about the actions of their local Jewry. The numerous reports that this effort generated didn’t amount to any proof of a global Jewish conspiracy, as Inuzuka and Yasue had hoped, but they nevertheless carried on with their efforts to understand the success of Jews.

In 1937, Yasue was recorded meeting with Abraham Kaufman, who would establish the Far Eastern Jewish Council. Their meetings included frequent discussions of how to bring more Jews to settle around Harbin. But by this time, the Japanese acceptance of Russian Whites as anti-Communist enforcers in the area led many Jews to fear pogrom-style attacks, and the community had shifted its mass to Shanghai. The following year, Kiichiro Higuchi expressed a similar sentiment to Yasue, and he requested that Hideki Tojo approve letting Jewish refugees settle in Manchuria, to which Tojo agreed.

In December of 1938, the Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, the Foreign Minister Hachirō Arita, Army Minister Seishirō Itagaki, Naval Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, and Finance Minister Shiegaeki Ikeda met to discuss the issue of Jews, and they agreed to issue a decision prohibiting anyone from expelling Jews from Japan or any Japanese imperial possessions in Manchuria and China. Since Japan’s alliance with the Nazis was becoming closer and more important, the Nazis effectively overlooked this action, but after the global Jewish boycott that resulted from Kristallnacht the month prior, the Japanese had become fully convinced that Jews would be a boon to their nation. So, this group of ministers also allowed nearly 15,000 Jewish refugees from eastern Europe to obtain asylum in the Japanese quarter of Shanghai, effective immediately.

Sugihara would follow suit, proving his righteousness after the outbreak of the Second World War. Working in the consulate, he was able to negotiate a deal with the Soviets to allow him to issue visas to local Jews, who would then be allowed to transit through the Soviet Union to Japan. But the Foreign Ministry didn’t approve of his efforts, and they told him that he could only issue visas if there was a destination beyond Japan, without exception. So, against their clear directives, he simply issued the transit visas to Japan, in as great a number as he could, until the Soviets shut down the embassy and sent him back to Japan on September 4ᵗʰ, 1940.

It’s not clear how many Jews Sugihara saved in his defiant act that was, he later noted, simply never brought up to him after he did it. At the very least, Sugihara saved thousands of Jews, with the most popular estimate being that he saved 5,558. Accordingly, around 100,000 Jews today owe their lives to Sugihara’s efforts—that’s almost 1% of all Jews alive today. Without the visas issued by Sugihara, there also wouldn’t be any original surviving European yeshivas either, as Sugihara and his Dutch counterpart Jan Zwartendijk alone managed to save the Mir Yeshiva.

Regardless of why Sugihara did it, the backfiring of anti-Semitic propaganda in Japan allowed Jewish refugees to land there, and it’s what allowed ancient European Jewish traditions to stay alive. Whatever the effect publications like The Protocols and their apparent vindication by people like Schiff had on anti-Semitism globally, they were, strangely, not all bad. For many Jews today, they were, shockingly, crucial.

In the modern day, what Westerners would certainly dub anti-Semitic publications seem to sell well in Japan, but as in the 1930s and ‘40s, they still don’t seem to provoke any ire against Jews. The Japanese seem to be some of the few people in the world who hear a phrase like “Jews control the global media, banks, and everything else”, who turn around and think “Wow. I want to be like that.”

And Japan is not alone! Across all of East Asia, ideas that are associated with the most vile strands of anti-Semitism in Latin America, the Middle East, India, Africa, Europe, and North America are little more than business advice and proof that you can achieve what you set your mind to in countries like South Korea and China! This isn’t some minor reporting item either; it’s supported by mainstream publications, like Newsweek, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and, most convincingly, Tablet Mag.

Does Love Win?

“Love Wins” is a popular slogan, but is it true?

Consider the 1972 Munich Massacre.