"Yes, and..." Urbanism

What can the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth teach us about effective zoning law?

Alternative subtitle: “What can we learn about zoning from how other places manage it?”

With little exception, the Anglosphere makes too little housing1 and has trouble building out vital infrastructure. The legal regimes in these countries give existing home and land owners enormous power over what gets built near them, making it difficult to densify and connect cities. In their current incarnations, those systems are reminiscent of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but their problems could be fixed if they transitioned to direct democracy.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the legislature (Sejm) had a rule that allowed for any member to immediately end the current legislative session. The liberum veto2 made it impossible to convene a legislative session, for reasons domestic and foreign. Namely, foreign powers were able to exploit the legislative deadlock by paying off lords to use the veto, so the Commonwealth could not react to problems. From the beginning, the extremely individualistic and egalitarian setup of the Sejm meant the Commonwealth was doomed.

Anglo-Saxon land use regimes provide individuals with something akin to the liberum veto, creating some of the world’s most effective Not In My Back Yard-ism. Private citizens can vote down permitting local projects and they can leverage state and local laws to stall projects indefinitely, or at least until the point where they fall apart since long waits doom builders. Local elected officials have many means to frustrate building and they’re easily captured by local concerns, interest groups, and various parochial interests.3

For a solution, look east—specifically, to Japan.

How Does Japan Build Cities?

Tokyo is an urban wonder, but it would be much less wonderful without land readjustment. Roughly one-third of all of Japan’s urban building was done through a process of replotting land parcels and reconstructing homes to increase local density and make way for new infrastructure.4 Conceptually, that looks like this:

In this diagram, you can see an area of low-density homes that has undergone land rights conversion, where, when two-thirds of the area’s existing homeowners agree, everyone’s right to their land is converted to the rights to an equivalent part of a new building that will be constructed on the land, potentially alongside other amenities, infrastructure, and additional buildings.

The key consideration in that last paragraph was how the decision to modify the land was made: through direct democracy by the area’s existing homeowners. The complex bargaining between local officials, activists, and landowners looking to build under different legal arrangements in the U.S. is radically simplified by putting the decision-making power in the lands of the people most affected by the land’s development. The question changes from “Will someone use the liberum veto?” to “Do the people wish to see their land improved?” If the answer is in the affirmative, the people win.

Surprisingly, this means that Japan has relatively weak eminent domain law in the sense that their setup makes more concessions to existing landowners. To understand why, consider a community where the owners of different plots, enumerated A through H, need to gain access to infrastructure. They’re originally set up like so:

In America’s eminent domain regime, one way to connect these plots to infrastructure is like this:

The owners of plots A and G had their land expropriated to make way for the road, sidewalks, and other utilities. The owners of B, D, and E, and to some extent F, were compensated for the loss of parts of their claims through eminent domain, and they benefit through asset appreciation resulting from the new infrastructure. The owners of C and H got to fully maintain their properties, while also benefitting from proximity to new builds.

The system of expropriations and remodeling is not terribly fair, and it operates against the will of many of the people, to the benefit of a lucky few. Now let’s look at how Japan does it:

With land readjustment, no one is expropriated. Everyone maintains a plot and infrastructure gets built. People only compromise on size, proximity, to other plots, and so on. As a means of provisioning urban infrastructure, this is obviously going to be more acceptable to large numbers of people than is the use of eminent domain. But is it better than simply not building at all?

People who already own land might wish to keep it a certain way. Land readjustment might not be for them, and it’s likely to make them very upset because the people around them might vote to change their claims around.5 But enough people will agree to land readjustments in enough places that it can have radical impacts on economic geography, rewarding those who accept it with access to new infrastructure and higher densities. There will even be some people who elect to have the government or firms build infrastructure on their jointly-held parcels, letting them bid to build on their land. When the building is through, it’ll be returned to its owners in their newly-arranged plots.

Consider, for example, the readjustment of the Obu-Hantsuki area of Aichi Prefecture between 1994 and 2002:

Or consider the development of this new town in Chiba Prefecture between 1989 and 2005:

Or, if you’re a real nerd, just consider this picture of the Tsukuba Express. Why? Because land readjustment was crucial for building it!

High-speed rail? It can be had with land readjustment.6 A sparkling new tower full of homes? Land readjustment. A new park, airport, school, stadium, subway, bus line, trolley, convention center, bike lane, or hotel? Land readjustment can bring these things to fruition by transforming complicated representative democracy questions into simple, one-off direct democracy ones.7

To continue reading about land readjustment, here are several links.8

Looking Back West

Japan is not the only country that uses land readjustment successfully. India, for example, has had several notable successes with it. Go just a bit further west from there and you’ll arrive in Israel, where similar democratic schemes have broken zoning deadlock and promoted urbanization.

More than a third of Israel’s new construction is done through two programs:

Pinui Binui: A program within which buildings are rezoned for rebuilding, with the choice to go through the process started through an agreement between homeowners and developers.

TAMA 38: A program where homeowners only need to make a deal with developers to update existing buildings built before 1980, or to demolish and build something else in place.

These programs are elective, hyper-local, and successful, demonstrating dispositively that elective upzoning is politically feasible in Western nations. Similar programs have also helped to build rail lines and other local amenities. But how do programs like this get implemented? They upset incumbents, so there’s definitely resistance.

In Israel’s case, the programs were tolerated because of a need for resilience to earthquakes and concerns about dilapidation to the country’s relatively dated and hastily constructed housing stock. The country’s previously poor housing stock was made in such a slapdash manner because it was built to allow Israel to take in massive waves of immigrants and refugees. Or in other words, there was a historical impetus for the development of a quality institutional setup.

A curious fact is that this makes Israel a bit like Japan. Part of the motivation for Israel’s housing policies also applies to the Japanese case, where the issue of earthquakes has always loomed large.9

Looking Even Further West

To get good housing policies given the political economy of incumbents who generally don’t want more housing, there has to be some impetus in place and a means of making new building tolerable. Israel and Japan have figured out their own ways of making this happen, and the country of France might be yet another good institutional model.

In the French case, the law since 1977 has held that, above some size threshold, buildings must be subjected to a set of heightened quality standards. These standards are binding past an “Architect Requirement Threshold”, whereafter licensed architects become the mandated preparers for building creation or modification plans. The plan “aims at ensuring that only aesthetically pleasing, durable, and safe new housing is built.”

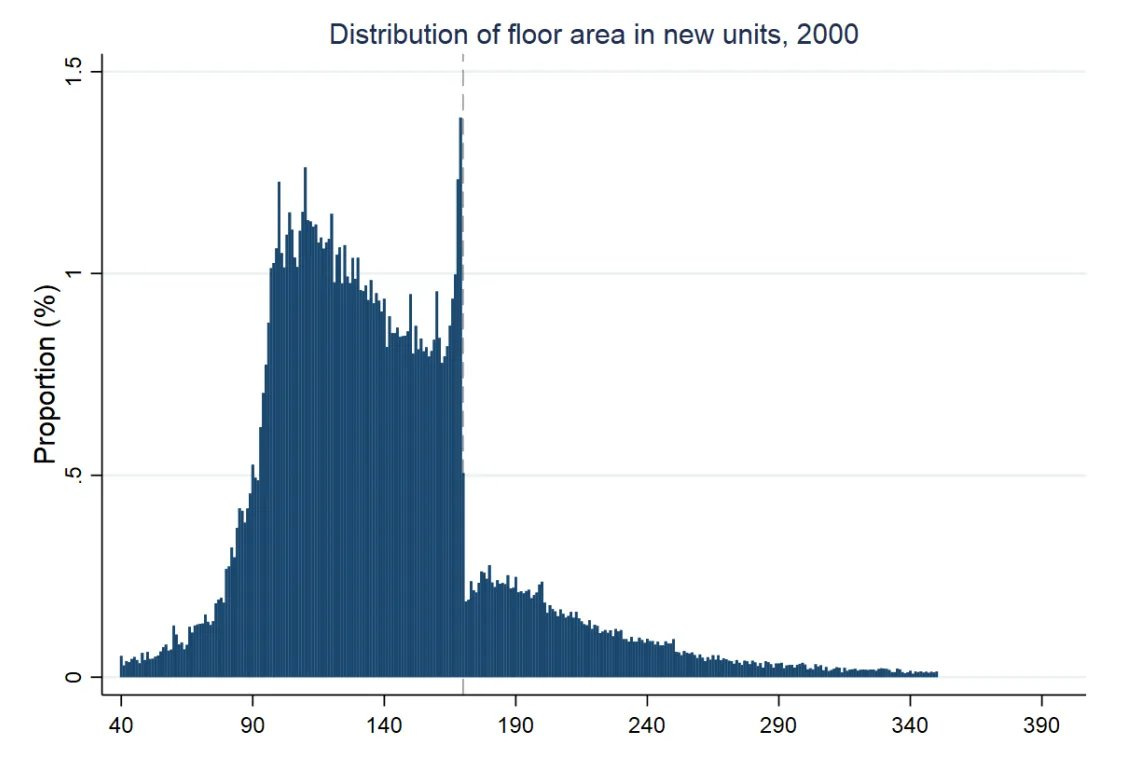

The thresholds are exploited. Developers try to avoid exceeding thresholds because of the added costs of contracting a licensed architect and meeting their exacting demands. This is highly visible in the distributions of floor areas in new units:

My point is less that France has issues with compliance with these sorts of regulations, more that it has thought of them, and that they seem like a fine concession. Imagine: What if homes could be built so long as they had a little added cost in the form of aesthetic review?

A major complaint at many zoning board meetings is that new homes being proposed are ugly. To that, France has generated a simple solution: mandate pleasing aesthetics and move on. Take locals’ views out of consideration and place the control in the hands of architects and bureaucrats whose duties are minimal—but necessary to satisfy the community—and whose demands cannot be extreme. The demands just have to be real, whereas in the current zoning board-dominated regime, they are frequently not. By that I mean, aesthetics are usually an excuse to reject building, which leads me to the French answer: accept the excuse, but take away the bargaining power it creates!10

Another westerly F-place worth mentioning here is Florida. In 2021, they passed a permitting reform bill for housing that made the state’s housing regime far more by-right than it was before. Under the bill, local jurisdictions are required to provide details about their permitting processes and the status of permit applications. This alone takes out a large portion of the issue with building by removing the opacity of the housing regime, but that’s not all.

Florida’s permitting reform bill also requires that permits are responded to in a timely manner. If a local jurisdiction does not respond within thirty business days, each additional day the permit is unanswered is a 10% refund of its total cost. If a permit is rejected, that’s not the end of it. Now, the jurisdiction must provide actionable feedback that can lead to correction and eventual approval. After this came into effect, Florida experienced an overnight building boom, and all because saying “Yes, and…” became the default.

Yes, and…

The techniques for building that I’ve outlined here all have one thing in common: they’re about getting people to say yes to building something. They’re things that enough people will find agreeable to allow something to be built. The overarching idea is simple: reformulate land use to take away the ability to say “no” or to otherwise stop building in its tracks. Instead, provide people with the ability to say “yes” with limited provisos that will help to leave them happier than if they had no input at all.

For the sake of clarity, limiting discretion is key, or even a place that adopts land readjustment will wind up held back by NIMBYs once again. The “and…” that comes when builders are told “yes” has to be sufficiently clear, final, and limited in scope, or it’s not really an “and…” at all—it’s a “no”.

The Agglomeration Imperative

Something must be done to promote agglomeration. By that I mean to promote not just urbanization, but different ways of allowing more people to get together in the real world. That includes not only high-density homebuilding in prime locations, but also the creation of rapid transport into those areas from far afield. Rail lines are a standout way to accomplish that goal, as they allow people to have their homes far outside of cities, but to easily enter cities rapidly, reliably, with little congestion and environmental impact, and at low cost.

Adopting mass rail transport generates a variety of benefits. As I’ve already suggested, it alleviates the demand for housing within cities. For two, it concentrates economic activity within certain areas of cities by placing it near stations, putting minds closer together while also making it possible to easily concentrate governmental resources like police11 in places where you can guarantee more traffic is happening. For three, it promotes geographic and social mobility due to its low user cost and time requirements.12

There are many other benefits to rail, but it’s also not the only thing that can be used to promote agglomeration. With the imperative and the means to have more homes and infrastructure provided by treating building as a matter of “Yes, and…” with land readjustment, democratically-supported upzoning, and aesthetic requirements, cities could demand and receive more green space, improved street lighting, designated zones where licentious activities happen (because if they’ll happen anyway, might as well have them happen around a bunch of police), and the room to work on other neglected aspects of city infrastructure, from fiber optic cabling on down to updates to sewage systems, accessibility, and more.

The benefits to agglomeration are small percentage growth dividends, and in the medium-to-long term, that means enormous returns. The price of delivering those returns could be as low as giving people democratic control of their cities.13

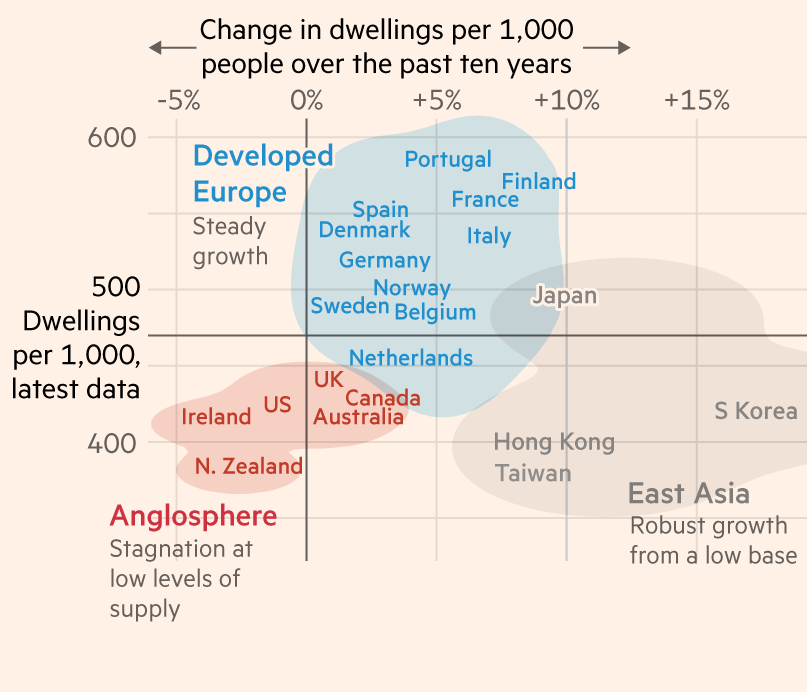

Cf. this. The problem with this response to Burn-Murdoch’s display that the Anglosphere has anemic homebuilding is that it seems to neglect that the Anglosphere clearly isn’t building enough, even if it’s building a lot in absolute terms, as evidenced by its extreme increase in housing costs. Consider the data provided by Aziz Sunderji over at Home Economics, in this article.

Firstly, the Anglosphere has had markedly increased prices:

Secondly, the Anglosphere has built unimpressively for how much population growth it’s experienced:

And finally, this dovetails with the building patterns of the Anglosphere being uniquely inimical to high-density urban building as Burn-Murdoch described. Burn-Murdoch showed that British and American attitudes towards building are not pro-density in the sense of supporting apartments/flats:

And the countries themselves are not high-density in terms of having high proportions of apartments/flats, or even just being very literally high-density:

These facts together suggest that the Anglosphere really is deficient at home-building in an important way that countries outside the Anglosphere generally are not.

Among homebuilding advocates, what I’m analogizing to the liberum veto is more often called a “heckler’s veto”, but I prefer the historical analogy.

Laws like NEPA can also make it impossible to build the infrastructure required for densification. As an example, consider the struggle to build bike lanes in San Francisco. The failure to build even simple infrastructure like that contributes to the veto power of local interest groups and activists because it can be cited as a justification to delay or revoke building projects.

It’s likely that much more than one-third of Japan’s urban development can be attributed to land readjustment after accounting for its indirect impacts on urban land allocation.

In Japan, the government and private developers can provide incentives to encourage people to agree to readjustment, and sometimes people feel compelled to agree because their property values may decline otherwise. It can take years for people to obtain the consent of landowners to remodel their land, so this is no panacea, but it is better than t he process not existing at all.

A major issue preventing it is how hard it is to acquire large swathes of land, and this simplifies doing that.

In theory, this system can also leave developers in a better position, since it can be fashioned in a way that lets them face all of their permitting barriers up-front.

Moreover, like Israel, Japan had to rapidly produce a large amount of housing in recent generations. In Japan’s case, the reason was World War II, and the policies from that era have stuck in some form or another. In Israel’s case, the issue was mass migration, and the poor policies of that era led to the better policies of today.

Something similar has been proposed in the U.K. To my knowledge, they have been met with limited success.

It might even promote electric vehicle adoption, as in China.

Also you have to reform NEPA (and, where applicable, its state-level equivalents) or it’s not even feasible to do major urban remodeling.

Korea, a housing market I have some familiarity with, has something like the land readjustment model described for Japan.

In Korea, the formation of a community organization to readjust the land tends to be a catalyst for the adjustment to happen. It only takes a few YIMBYs to create the community organization in the first place. Then, it hits the news that the organization exists. Prices in the reorganization area go up as people who want in on the reorganization buy from the (smaller) number of people who decide they aren't interested and sell out.

The large ecosystem of people (real estate firms, design firms, financial institutions, law firms, first time home buyers who want to lock in a place for when they are 'ready', etc) who benefit from reorganization create momentum for a reorganization to be negotiated and then happen.

Often the people that started the community organization get democtratically overthrown by a new coalition of owners in the community, often from the influx of new owners who came in when the news of the community organization broke. This can happen several times through the process if enough owners become unhappy with the process, each election being vibrantly contested.

Normally, the community ends up wanting something more ambitious than is compatible with some overall city plan and the City bureaucracy intervenes to dial back the ambition of the community organization - though too much of that has costs for local politicians at the next municipal election.

I think this is an extremely alarming article, because the LAST thing we want as a country is to go down the path of Japan, China, and other Asian countries with extremely dense housing and CATASTROPHIC, CIVILIZATION-ENDING BIRTH RATES:

https://x.com/MoreBirths/status/1833662042839949402

Whatever zoning law ends up with huge skyscraper condos where we cram couples who decide to have, at most, 1 child, we need to fight against it tooth and nail. The evidence is overwhelming that a handful of spread out houses are the only path toward a pro-natal future.