Written by Cremieux Recueil.

The three brothers shown below were members of Israel’s elite special reconnaissance unit, Sayeret Matkal, many of whose members would go on to become Israeli politicians (prime ministers, defense ministers, members of the Knesset, etc.). The middle brother is the oldest. This Harvard man, who had turned a failing tank brigade into the foremost unit in the Golan Heights, was killed while leading the Israeli assault squad in the Entebbe raid in 1976.

The events preceding the raid were familiar to anyone who followed the news at the time: a plane was hijacked; there was a request for ransom; and then negotiations began. Yet the finer details are worth rehashing. On June 27th, 1976, Air France Flight 139 departed from Tel Aviv carrying 246 passengers and twelve crewmen. When the plane touched down in Athens, Greece, it picked up a further fifty-eight passengers, four of whom were hijackers. The plane then departed for Paris but was soon hijacked by two Palestinians from the Marxist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and two Germans from the Marxist Revolutionary Cells group. It was immediately rerouted to Benghazi, Libya.

The plane was held in Benghazi for seven hours while it refueled, and during that time, the hijackers released a woman who claimed to have a miscarriage due to the stress of the event. Shortly afterward, it left Benghazi for the flight’s ultimate destination: the Entebbe airport in southern Uganda. When they arrived, the hijackers were met by four friends of theirs and they received support from Ugandan dictator Idi Amin’s forces. It was there they began to make their demands of the Israeli government. Ultimately, however, nothing worked – so Israel had to use force to free the hostages.

After the Israelis received permission to refuel their planes over Kenyan airspace, the raid began. The assault team departed from Sharm el-Sheikh and flew over the Red Sea before crossing into Ethiopia and then into Kenya. They refueled and proceeded towards Entebbe, where they landed at 23:00. The team was aware that Idi Amin was flashy, opting to drive around in a Mercedes with an entourage of Land Rovers, so they brought a black Mercedes and some Land Rovers along with them in the hope that they could use them to get through checkpoints. But this didn’t work: when they approached the first checkpoint, the Ugandan sentries stationed there became suspicious since they knew Idi Amin had recently purchased a white Mercedes. After being pulled to the side, the Israeli commandos shot the sentries with silenced pistols, but another commando was a bit hasty, and open fired with an unsuppressed automatic rifle. The team had to adjust their plans.

The commandos ran into the terminal yelling, “Stay down! We are Israeli soldiers!” in both Hebrew and English. Two Israeli hostages stood up and, because they’d been told to stay down, were mistaken for hijackers and were shot by the commandos. Another hostage got caught in the crossfire after the hijackers opened fire on the Israeli commandos.

After dispatching one of the German hijackers, the commandos made their way over to the hostages and yelled out, “Where are the rest?” The hostages pointed, and the commandos threw grenades in that direction before running in and killing the remaining hijackers. Now they had to deal with evacuation.

The C-130 Hercules the Israelis had brought with them were stationed on the tarmac, and several armored personnel carriers had been unloaded. Meanwhile, the Israelis had destroyed nearby Ugandan MiGs to prevent them scrambling for a pursuit. The team brought the hostages towards the planes and Ugandan soldiers began to fire on the escaping Israelis from the control tower. The commandos suppressed Ugandan fire with RPGs and machine guns, and were ultimately able to save 102 of the 106 hostages in the airport. Ten of the surviving hostages and five of the commandos suffered injuries in the fight, compared to 7 dead hijackers, 45 dead Ugandan soldiers, and somewhere between eleven and thirty Ugandan aircraft destroyed. The Israeli commandos suffered one death: the boy in the middle of that picture at the beginning of the article.

The deceased had no children, but was survived by his two brothers – who would go on to become a successful radiologist and playwright, and the prime minister of Israel, respectively. His name was Yonatan Netanyahu, and his brothers are Iddo and Benjamin.

Each of the three brothers was highly successful, and Yonatan was considered the brightest of the three. If his life hadn’t ended so suddenly and senselessly, it’s suspected that he would have become the Israeli prime minister instead of his brother. Regardless, all the boys showed talent, and they accomplished an enormous amount. And why shouldn’t they? After all, Benjamin Netanyahu has claimed descent from the esteemed rabbi Vilna Gaon and talent is very general. One need only look at the accomplishments of former members of the Sayeret to see that the skills involved in being a commando clearly transfer to other domains, even though they don’t have any obvious relevance to things like excelling in politics, medicine, religious scholarship, science, or the arts.

Even if Netanyahu’s claimed lineage is inaccurate, it’s difficult to dispute his family’s accomplishments. His grandfather Nathan Mileikowsky was a successful activist, writer, and rebbe during the Emancipation. His father Benzion was a respected historian and an Ivy League professor who also found the time to be a successful activist. His cousin Elisha Netanyahu was a mathematician who served as the Dean of the Faculty of Sciences at the Israeli Institute of Technology, and he married Israeli Supreme Court justice Shoshana Netanyahu (née Shenburg), whose son was the successful computer scientist Nathan Netanyahu.

The reason this is interesting is that the family clearly has an extremely high level of talent, and its members have applied their skills in numerous different ways. They are, in short, elites. They’re elite at everything they do, from apprehending terrorists to leading nation-states to administering the law to commanding congregations to developing optimal algorithms for nearest-neighbor search and more. It’s unlikely any of them would have failed in life.

The Netanyahu family is interesting, but their level of talent is far from unique. They can be readily compared to the numerous cousins involved in the development of the atomic bomb, or with other esteemed families like the Darwin-Wedgwood-Galtons:

Amazingly, if you transplant a number of esteemed families to foreign soil, you might just create an elite group out of them. As it happens, this sort of process has been studied. In 2014, UC Davis economic historian Gregory Clark defended his then recently-published book The Son Also Rises against some criticisms that Aporia readers might consider inane. Yet he pointed out something important:

Studies of social status within ethnically homogeneous groups show that genetics plays a substantial role in outcomes. Thus if elites and underclasses are drawn from parent populations by selective recruitment, they will differ genetically from the general population. It will take many generations for those differences to dissolve. This is not an “ugly” fact. It is not a “beautiful” fact. It is just a fact.

This fact slams head-first into our modern, egalitarian sensibilities. And yet, it is still true: many processes can trivially create differences between groups in terms of the genetics underlying status attainment.

One can skim from the top of the distribution in, say, Lebanon, and create an accomplished elite in Mexico. One can do the same thing in America by importing doctors from Africa. The possibilities are limitless, and immigration is only among the most obvious ways to create an elite. Affiliative and assortative processes abound! Let’s consider some of the processes by which elites can be made.

Japan

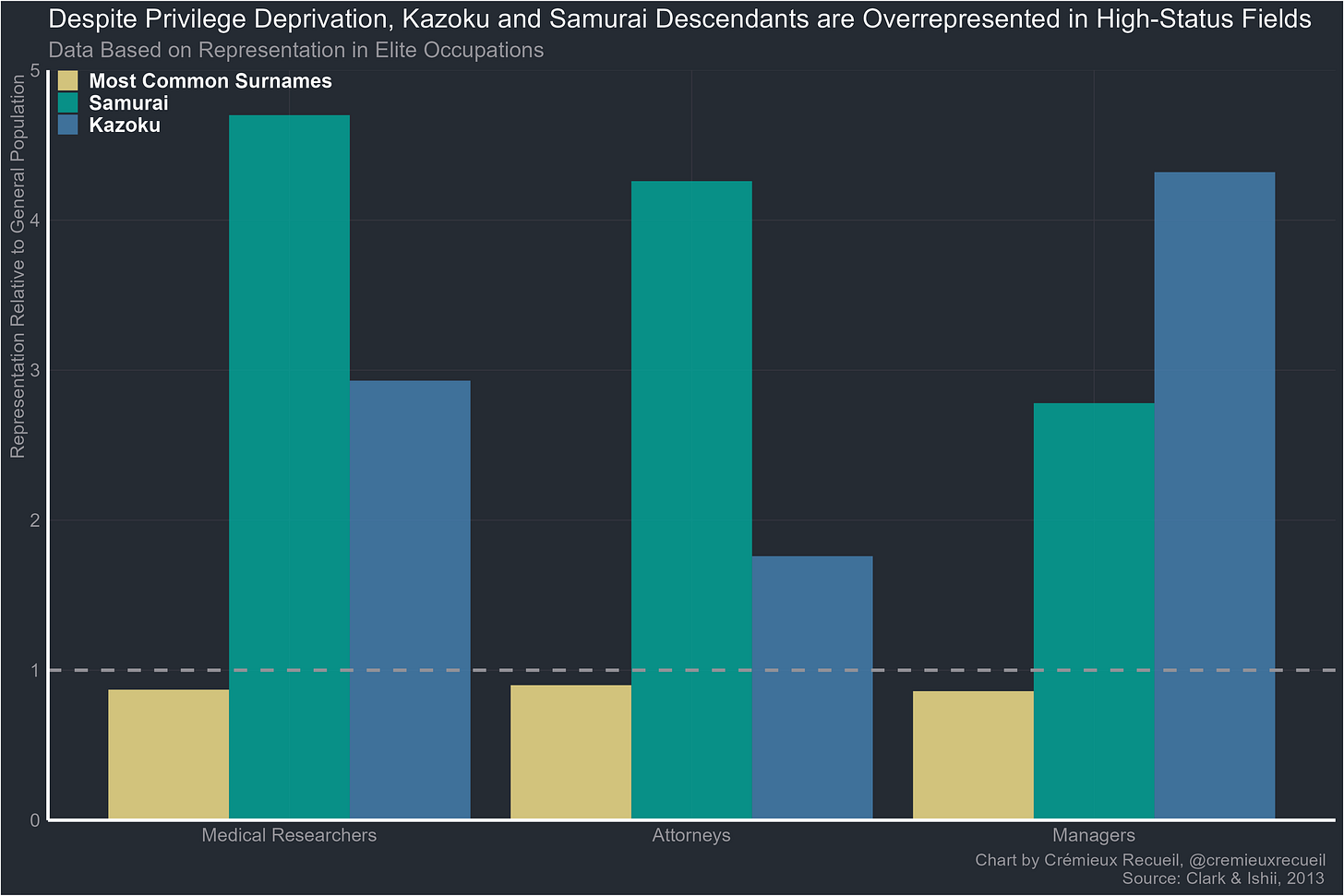

Immigration is a powerful force, and Japan is a country known for its long-standing restrictionism. It’s not surprising, then, that they don’t have imported elites. But they do have homegrown ones. The two most distinct are the well-known Samurai and the lesser-known Kazoku. As it happens, Gregory Clark detailed the experiences of these groups in The Son Also Rises and in a 2013 paper with Tatsuya Ishii.

The Samurai are an ancient, hereditary nobility of warriors that formally existed between the 12th century and the Meiji era. The Kazoku are a more recent invention that lasted between 1869 and 1947. The reason for their disestablishment in 1947 specifically should not come as a surprise: just as the reformers of the Meiji Restoration had ended the Samurai, the Americans ended the Kazoku when they wrote Japan’s modern constitution. A major thing the two groups have in common is that both lost their formally-granted social status and yet both managed to maintain their stations.

The Kazoku peerage initially comprised just 427 families, but its membership expanded through recruitment of individuals who distinguished themselves in the service of Japan. By 1946, it comprised 1,011 families, meaning that the number more than doubled over its brief existence! To understand just how well these groups have maintained their elite status, consider their incredible overrepresentation in academia. Even today, after losing their government stipends, land rights, and other privileges, they’re more than ten times as likely as non-Samurai or Kazoku Japanese families to have published scholarly articles:

The Kazoku and Samurai are also overrepresented among medical researchers, and to a very extreme degree:

Compared to holders of Japan’s most common surnames, they’re also far more likely to be attorneys and managers:

Golden Convicts

One of the other incredible things about social status that Gregory Clark has documented is that the Australian class system – which is often held to be much looser than its English equivalent – was actually just as rigid.

Interestingly, Clark also showed that convicts in Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania) were positively-selected! They weren’t enormously positively-selected, but they did have somewhat higher status than the norm. And this makes sense: convicts were often sent because people with their occupation were requested by colonial authorities, or because they were debtors. Note that being a debtor meant a person was among the portion of the population that had a high enough income, or had possessions like land, which required them to pay taxes for which they could become a debtor.1 Being able to commit a crime made you somewhat elite! Couple this with Tasmania’s reputation as a place that was notoriously harsh, and you have a recipe for creating relatively elite groups.

Bengali Brahmin

In West Bengal, though the upper classes have had surnames for longer than members of the lower classes, the advent of surnames in the region is, for the most part, relatively recent. Many of the West Bengali upper class acquired their surnames around the time of the arrival of the East India Company. When these upper-class groups petitioned the East India Company, we see an overrepresentation of names like Banerjee, Khan, Haldar, Mandal, Mitra, Sen, Datta, and Chatterjee. Several of the names of those petitioners are notably Hindu in origin, and they belong to the Brahmin.

Remarkably, Clark & Landes found that even today, in an era where explicit quotas for lower castes and underrepresented groups have been implemented, the Kulin Brahmin are overrepresented in elite occupations. Consider these recent figures for doctors and judges:

As the paper showed, this overrepresentation is also observed among Indians in America. What’s even more interesting is that explicit reservation policies failed to make much of a dent in these status differences between 1920 and 2009. Note that no Kulin Brahmin obtained their doctor position through reservations. The country’s historically-unprecedented system of affirmative action failed to change the relative positions of the Kulin Brahmin. In fact, things still seem to look how they did in the era of the East India Company, which says something about the persistence of social status.

The Jizya, Freddie Mercury and the Jizya-Gavur

Like many minorities, Egyptian Copts have been historically persecuted. Yet today, the Copts are exceptionally well-off, and not just abroad, but also in their homeland of Egypt! In fact, the persecution may have made them well-off.

If you are ruled by Muslims and are not yourself a Muslim, you are supposed to be under their protection, making you a dhimmi. Just as Muslims had a duty to protect the dhimmi, the dhimmi had a duty to their Muslim overlords: a duty to pay the jizya, a poll tax placed on non-Muslims who wanted to keep to their faith.

The tax had qualifications: it applied only to free, sane adult males who were not elderly, physically infirm, or suffering from disease, who had not become hermits or slaves, and who were not simply traveling through Muslim lands. The tax could also sometimes be avoided by serving in the military for a Muslim ruler. Muslims, by contrast, paid alms in the form of the zakat, which was not always mandatory, and was usually lower than the jizya – which was mandatory.

Muslim rulers upheld their end of the bargain when it came to the workings of the jizya. For example, after the assassination of ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab by a Persian dhimmi, he proclaimed from his deathbed that “I urge [my successor] to take care of those non-Muslims who are under the protection of Allah and His Messenger in that he should observe the convention agreed upon with them [the covenant of jizya], and fight on their behalf and he should not over-tax them beyond their means.” And indeed, Muslim rulers did not tend to overtax with the jizya, because it was a major source of revenue.2 Some rulers, however, were more pious. They imposed higher tax rates, leading to greater numbers of conversions to Islam.

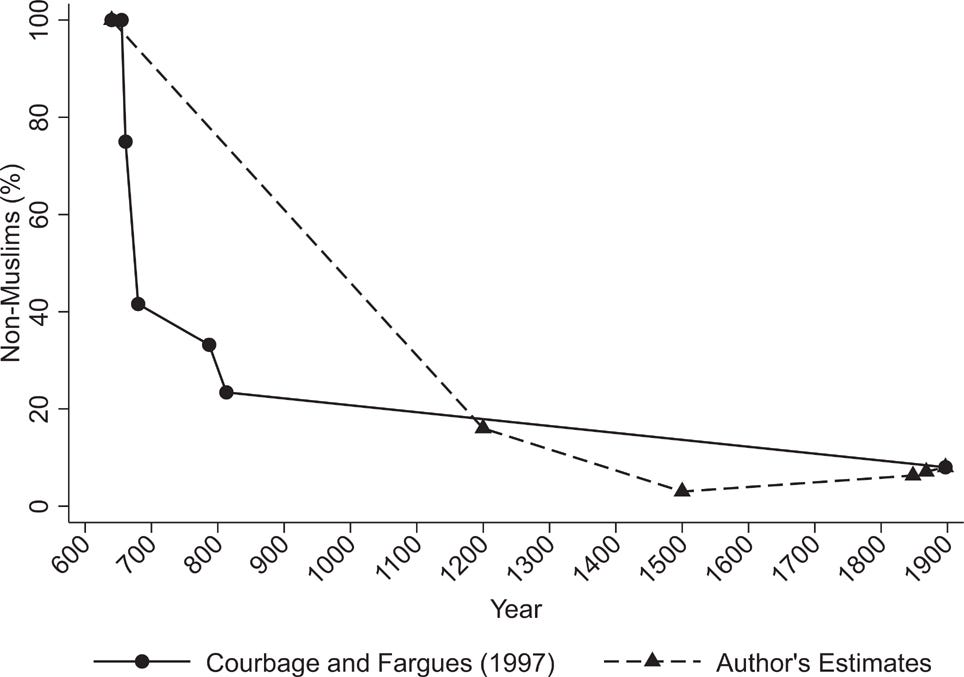

Economic historian Mohamed Saleh has detailed the effect of this jizya on Egypt’s Coptic Christian population. To begin with, consider what the non-Muslim (Coptic-inclusive) population of Egypt has looked like over time:

Before Islam arrived in Egypt, Copts were a major part of the population, alongside Jews and non-Coptic Christians like Melkites. After the Islamic conquest of Egypt by ‘Amr ibn al-As between 639 and 642 AD, the Coptic share fell rapidly due to conversions, murders, and outmigration. Here’s what the tax burdens faced by Copts and Muslims looked like:

Because the rule in Egypt had become ‘pay up or else’, those places that had higher jizya burdens have considerably smaller Coptic shares in the years 1200, 1500 and the period 1848-68:

Poorer Copts simply could not pay up, so they had little choice but to convert. Accordingly, we see divergence in the occupations where Muslims and Copts were represented:

Did the jizya create other elites across the Muslim world? Kukić & Arslantaş studied its effects in Bosnia. The Kingdom of Bosnia existed between 1377 and 1463, when it was conquered by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, leading to a wave of conversions:

Between 1468 and 1600, Bosnia went from being a Christian country to being around 70% Muslim. Thankfully, the Ottomans kept good tax data. These show that settlement or town-level household incomes in 1468 were negatively related to Muslim shares in 1604, even when controlling for many potentially confounding factors. The association even holds for the year after Bosnia was freed from the Ottomans: income per household was negatively related to Muslim shares in 1879 too. This effectively replicates the process of selective conversion that Saleh documented in Egypt. Kukić & Arslantaş wrote that the jizya “stimulated low-income households to adopt Islam upon the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia”. Yet “patterns of religious affiliation persist after the initial conversion process”. In other words, despite the Ottoman yoke being cast off, many of those who converted remained Muslim!

The data these authors had access to did not show that Bosnian Christians were highly-educated like Coptic Christians are in Egypt. Ethnic cleansing and selective emigration might have contributed to the lack of any apparent Christian bonus in modern-day Bosnia. Tito’s Yugoslavia also worked to eliminate ethnic differences through public sector quotas that modern Bosnia and Herzegovina hasn’t eliminated, so perhaps the markers of selective conversion in Bosnia have been covered up or quashed by history.

Christians are also notably absent in other parts of the former Ottoman empire. Shortly before the establishment of the Turkish republic, that country carried out a genocide of Armenians, Assyrians and Greek Christians – which was certain to have wiped out some of their wealth. The republic also enacted the Varlık Vergisi (a wealth tax that was later characterized as explicitly discriminatory) with the goal of impoverishing non-Muslims, who saw it as the return of the "jizya gavur", or the jizya for infidels. It is perhaps the closest a government has ever gotten to writing up a list ranking ethnicities by how much they hate them. At the top of the list, Christian Armenians were forced to pay an incredible 232% rate, followed by Jews, who had to pay a 179% rate. There was clearly an ethnic element to this tax because Christian Greeks were faced with a rate of “only” 156%. Muslims, on the other hand, were taxed at an extremely low rate of 4.94%. It’s no wonder this caused a massive transfer of wealth to Muslims and left a huge number of non-Muslims enslaved in prison camps, deprived of their livelihoods, and in many cases, dead by their own hands.

The Parsis are another very accomplished ethnic group. They’ve produced many famous people and earned a reputation for charity. Their most famous Western member is the singer Freddie Mercury. Parsis were a Zoroastrian group that lived in Iran. Under the Rashidun caliphate, Zoroastrians disproportionately manned governmental roles. Yet when the Umayyads came to power, Zoroastrians were banned from manning those posts. Coupled with several other forms of persecution, this inspired many Zoroastrians to leave the country, whereupon they became the Parsis. And because they could escape persecution by converting to Islam, this emigration episode was again somewhat selective.

I have to read?

The story of how Jews became successful in Europe is well-known, so I won’t discuss it here. But the story doesn’t begin in Europe. In fact, as the economists Botticini & Eckstein have shown, the story of Jewish success started at least 600 years before Islam existed.

At the turn of the first millennium, Judaism was the majority religion in the land of Israel. It was split between groups like the Samaritans, Essenes, Zealots, and most importantly the written Torah-promoting Sadducees who had adopted Hellenistic culture, and the written and oral Torah-promoting Pharisees who opposed the adoption of any aspects of Greek culture and language. Around AD 63-65, Joshua ben Gamla – who was sympathetic to the Pharisees – proclaimed that every Jewish father had to send his six-to-seven-year-old sons to primary school, and that, barring mental infirmity, Jewish men ought to be literate.

This choice of date for the mass advent of Jewish literacy culture isn’t without its critics. As Botticini & Eckstein noted in their book The Chosen Few, other scholars have contended that the need for primary schools in Judaism was established around 70 BC; other scholars have argued that the effort began even earlier under Simeon ben Shetatch. But these quibbles don’t make a difference to the fundamental thesis, as we’ll see.

When the hope of a new temple was destroyed after the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Pharisees gained a major advantage over the Sadducees because they didn’t participate in the rebellion, leaving them relatively unscathed and better able to advance their project of universal education. They went so far as to replace the practice of sacrifice with the practice of Torah study. This effort succeeded to such a degree that by the time the great rebbe Judah ha-Nasi had finished redacting the Mishna around AD 200, Jews who did not educate their sons had become known as the amei ha’aretz, or the people of the land. Because the Jewish community was now literate, being am ha’aretz letorah carried a major social penalty.

At this time, Judaism was the only religion in the world that forced fathers to educate their sons. The Pharisees had thereby given Jews an incredible advantage. Yet interestingly, this was not the intent of the measure! The Pharisees wanted boys to be able to go to the front of their synagogue and read the Torah in Hebrew, which was not very useful for much of the Jewish diaspora, which resided in places where people instead spoke Greek, Latin or Aramaic. Moreover, this cultural revolution happened without an initial, corresponding change in the economic niche Jews occupied.

With this historical background in mind, Botticini & Eckstein formulated a model. Prior to the educational reform that made Judaism so unique, “both Jews and non-Jews are assumed to derive utility only from consumption, because no religion required literacy.” After the reforms, “Jewish and non-Jewish individuals are identical from the production point of view but are different in terms of their religious preferences … Jewish farmers derive utility from their children’s and their own Hebrew literacy.” They then got to the historical evidence for those predictions.

Firstly, the Jewish community was, indeed, composed of farmers at the beginning of the period in discussion:

Because farmers don’t derive much utility from reading, education was basically just a drag on their time. As Botticini & Eckstein noted, they were living at near subsistence levels, so the burden of educating their sons was often too much to handle, leading some Jews to live with the shame of being am ha’aretz letora and others to leave the religion entirely.

The dynamics of conversions between AD 1 and AD 750 are remarkable: the Jewish population shrank from almost five million people in the first century AD to fewer than 1.5 million by the eighth century. This change wasn’t entirely due to conversions: other populations also shrank, due to various massacres, wars, famines, disease, expulsions, etc., but the Jewish population shrank much more. The two primary religions these Jews converted to were Hellenistic paganism and Christianity. With the decline of Hellenistic paganism, Christianity became practically the only religious exit for Jews looking for an alternative to the faith.

Early Christianity aimed to peel off individuals from other faiths who had low socioeconomic status. This helped Christianity to grow rapidly. When the Edict of Milan was brought down in 313, tolerance of Christianity was enshrined in Roman law. After the Council of Nicaea, Christianity was free to spread across the Roman empire, and as it grew, the conditions for Jews became somewhat less favorable. Under Constantine, it was declared that Jews could not harm Jewish converts to Christianity. That seems perfectly reasonable – but the decrees became weirder with time.

Under Valentinian, Jews could not disinherit their children who chose to convert. Under Theodosius, the death penalty for harming converts was altered to a death penalty by fire. Under Honorius, things got somewhat better, as Jews who converted to Christianity could now go back to Judaism. Under Arcadius, Jews were forbidden from converting to Christianity for economic reasons. And under Justinian, Valentinian’s order was reiterated. Several of these emperors imposed various restrictions on Jewish activities, such as banning the building of new synagogues or the buying of Christian slaves. Although Jews were not forced to convert, many did. Those who did not were, essentially, a highly- and increasingly-literate class of farmers who weren’t allowed to do very much with their literacy.

When the Muslims came, they accepted the existence of Jews and let them worship, while also reducing restrictions on them. They also allowed Jews to finally apply the literacy they’d been selecting for by expanding urbanization. As the following table shows, the Abbasid policy of developing places like Baghdad and Samarra was a rousing success. The Muslims also created numerous cities that were not central to the Caliphate but were nonetheless larger than anything in Europe – and would be for four hundred years.

All this was very good for the Jews. As Botticini and Eckstein noted:

The growth of new cities, towns, and administrative centers in the Muslim Near East vastly increased the demand for skilled occupations. The literate Jewish rural population in Iraq and later in all Muslim lands moved to urban centers, abandoned agriculture, and became engaged in a wide range of occupations: crafts, trade, moneylending, tax collecting, and the medical profession. This occupational transition took about 150 years and, by 900, almost all Jews in Iraq, Persia, Syria, and Egypt were engaged in urban occupations.

This is how the story of Jewish success began. Jews opted into well-paying occupations thanks to their literacy, which had come about through a process that selected out less elite Jews. In their new economic niche, education took on a more secular character and emphasized other languages, making it even more advantageous to be Jewish. Since their Muslim peers mostly focused on religious education and the memorization of the Qur’an, the quality of their education was far lower.

Under Muslims, Jews had to pay the jizya, but this tax was generally less of a burden than the cost of education, so after Jews had entered their new economic niche, it wasn’t a major source of conversions. Forced conversion events were more of a problem.

Jews leveraged their literacy, their court system, and their international systems of communication with other Jewish communities, to get ahead in long-distance trade and eventually spread to Western Europe. When a Jew moved within the Caliphate, they simply had to pay the jizya, but were otherwise free to do so. When they moved to Western Europe, they faced a mountain of charters, regulations, taxes, and other burdens like having to ask for express permission from local priests and bishops, so those who did go there tended to be elite – the elite from among the elite, as it were.

By the time of large-scale Jewish migration to Europe, Jews were elite relative to Christians in Europe. The fact that there were charters regulating Jews in high human capital activities is clear evidence for high Jewish human capital. But there’s also the fact that rulers actually vied for Jews to settle in their demesnes, cities and towns. Botticini & Eckstein recounted numerous instances of this happening, such as the following:

In 1066, William the Conqueror brought some Jews with him (when he conquered England) in order to collect taxes and to obtain help with financial matters. In 1084 Bishop Rüdiger of Speyer in Germany explained that, ‘when I converted the village of Spyres into a city, I believed to increase the dignity of our locality a thousandfold if I assembled there Jews too’. He invited a group of Jewish merchants from Mainz, who were granted complete freedom to carry on their commercial enterprises in exchange for protection and exemption from tolls.

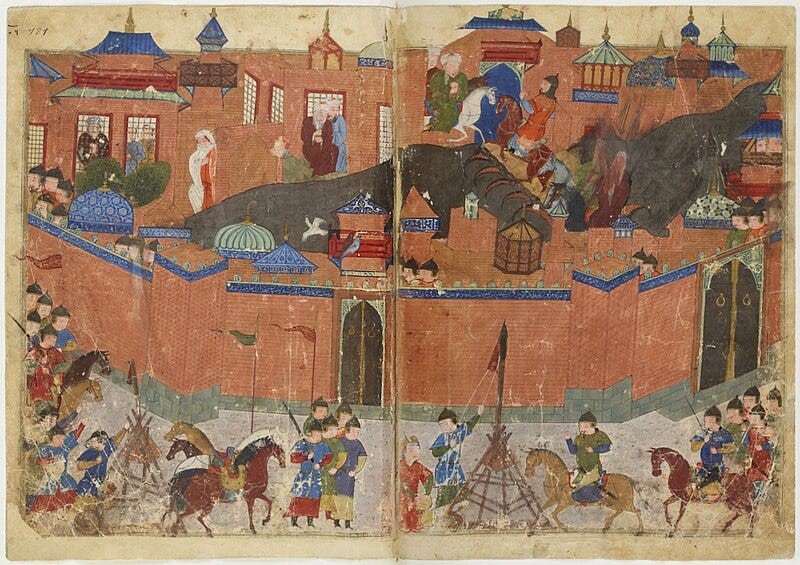

When the Mongols invaded the Near East in the 1250s, they crushed the economy of the region. The Sack of Baghdad (pictured below) alone resulted in the execution of the Caliph Abu Ahmad Abdallah ibn al-Mustansir bi'llah and the death of all 50,000 Muslim soldiers who defended the city, in addition to more than 500,000 civilians. The estimate preferred by Botticini & Eckstein was near the higher-end of Western estimates, at about 740,000. For the world at this time, this was an incredible level of devastation. Even today, it would be considered immense! As a result, Baghdad was turned from the jewel of the Near East into a backwater.

The devastation wrought by the Mongols in the Near East didn’t end until the Mamelukes managed to defeat them in battle, whereafter their conquests in the region ceased. But the Near East was now barren, and the Jewish population experienced a major relative decline, despite being largely spared from Mongol massacres. The reversion to subsistence farming coupled with the dual burdens of having to educate their sons and pay the newly-elevated jizya compelled Jews to convert at higher rates.

This view is mostly consistent with the more popular explanation for Ashkenazi brilliance put forward by Cochran, Hardy & Harpending. Here’s what Botticini & Eckstein have to say about the two theories:

Cochran, Hardy & Harpending maintain that there is evidence of higher-than-average cognitive abilities of Ashkenazi Jews and that this may be the outcome of centuries of prohibitions and restrictions on the occupations that Jewish people could practice. We do not have a strong view in favor of or against this argument … On the one hand, one prediction of our model—that individuals with low cognitive skills were pushed out of Judaism once the religion made literacy and education the main requirement for belonging to the Jewish community—may be consistent with this evidence on cognitive abilities. On the other hand, as we emphasize … the Jewish people left farming and selected into urban skilled occupations well before any restriction or prohibition was imposed on them.

Transmitting status shocks

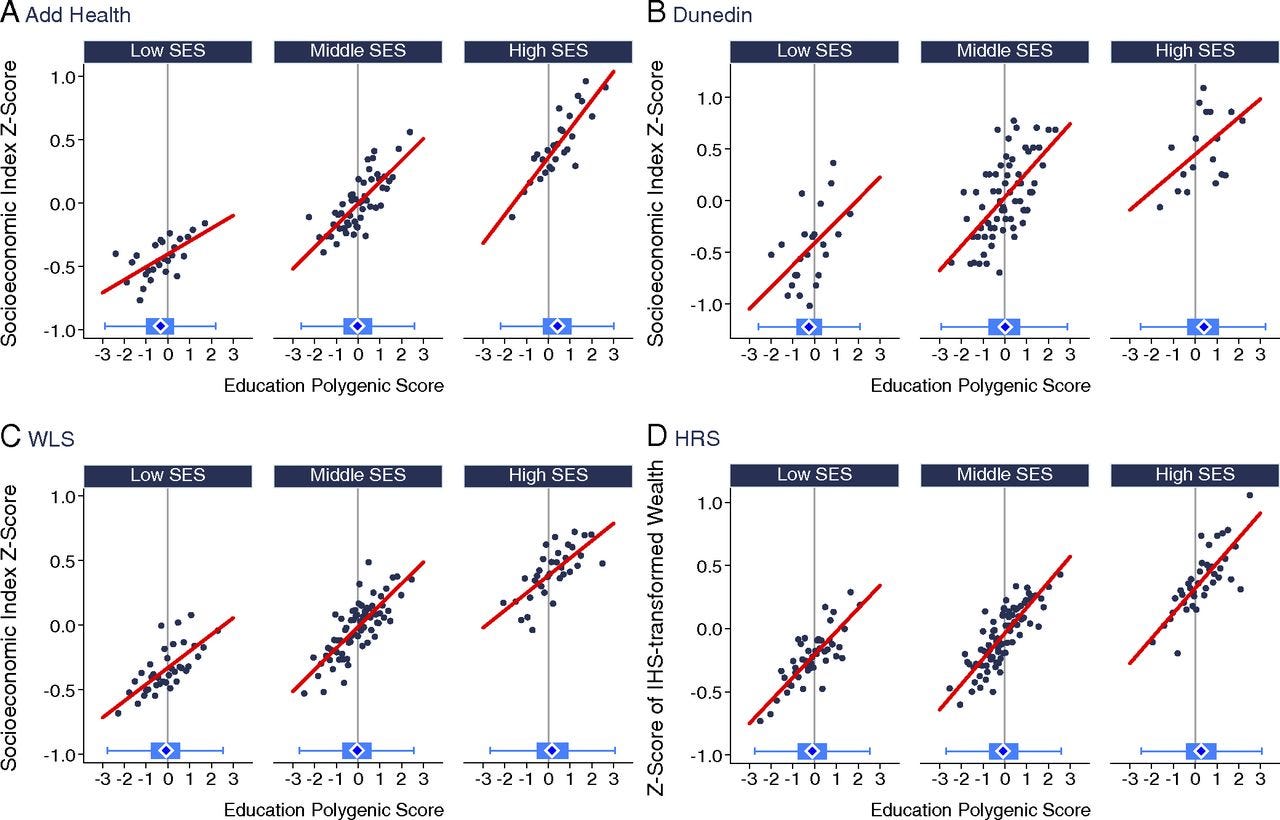

A brilliant recent paper showed that economic shocks can be transmitted genetically. The paper used biobank-scale data from Britain and Norway to investigate the effect of sibling birth order on the education polygenic scores of people’s spouses. But before explaining further, some background is required. Specifically: richer people have better genes.

What makes a set of genes "better" or "worse" when it comes to the attainment of a high level of social class is the degree to which the genes produce phenotypes that are conducive to social class attainment. For example, if being extroverted means that you earn a higher income, any genes that promote an extroverted personality will come to be associated with social class over time.

In Western societies, genes that promote educational attainment are also associated with social class. Note that these genes affect traits that are relevant to socioeconomic status both within and between classes, as well as within and between families! Here's an illustration of how genetic variants associated with educational attainment are stratified in four different cohorts from the U.S., U.K., and New Zealand:

In these studies, individuals who had better genes than their parents tended to be upwardly mobile. This finding has also been replicated in another cohort based in Minnesota. Matt McGue and colleagues showed that when a child has greater cognitive and noncognitive skills, and higher polygenic scores for those traits, they tend to move up. The result even holds when comparing siblings: the one with better skills tends to move up, whereas the one with worse skills tends to move down:

But I digress. The new paper explores how genes come to be associated with social class: Abdellaoui and colleagues showed that if there's a shock to a person's socioeconomic status, it may get transmitted intergenerationally through genetic means.

This doesn't have to do with epigenetics. It has to do with sorting on the mating market: when people mate assortatively on status-related traits, they aren't sorting themselves into couples based on their underlying genes, but on the appearance of those genes in the real world. So if someone manages to earn higher status than expected given their genes, they are likely to marry someone whose status is closer to what you'd expect for a person with better genes. In their paper, Abdellaoui and colleagues exploited the fact that birth order is associated with a person’s social status but is independent of their genetic endowment:

It is known that earlier-born children receive more parental care and have better life outcomes, including measures of SES such as educational attainment and occupational status. On the other hand, all full siblings have the same ex ante expected genetic endowment from their parents, irrespective of their birth order. This is guaranteed by the biological mechanism of meiosis, which ensures that any gene is transmitted from either the mother or the father to the child, with independent 50% probability ... We can therefore use birth order as a 'shock' to social status.

The size of this shock in Great Britain was modest: one additional elder sibling translates into a 7.9% lower chance of attending university, 0.077 standard deviations lower income, 0.27 points lower fluid IQ on a 13-point test, 0.7 centimeters smaller stature, 0.043 points worse self-reported health on a 4-point scale, and 0.19 points higher BMI. Birth order effects also showed up in Norway.3

In both countries, a negative birth order effect on a person's own status predicted worse genes in their spouse. This means that people really are exchanging status for a "higher-quality" spouse! Different mediator variables were available in the analyses for the two countries. Here's how the birth order effects were statistically mediated:

In both countries, the biggest mediator was education! By improving a person's chances of getting a university education, being born earlier improved the likelihood that they'd meet a high-quality spouse. The implications of this finding are considerable.

Victimization and elite formation

There is some evidence that the forced migrations of Poles from their traditional lands in the Kresy territories to the Western Territories after World War II might have encouraged them to value human capital formation more than physical capital formation. And something similar might have reinforced the formation of human capital among medieval Jews, and perhaps other historically-persecuted groups like the Huguenots.

In 1987, the government of the Republic of Fiji was taken over in a series of military coups. After the takeover was completed, the government enacted affirmative action policies that favored ethnic Fijians over Indians, and wrote a new constitution that allowed racial discrimination. Suddenly, laws cropped up making it harder to live and work as an Indian: they could no longer hold many university positions or earn a taxi license, and the government disfavored them when it came to starting a business. But if the Indians wanted to leave, they were allowed to do so.

After the coup, Indians began to invest more in their human capital so they could leave for places where they wouldn’t be the targets of discrimination. Investing in human capital was practically their only option since all other avenues were legally proscribed. Accordingly, educational attainment for Indians in Fiji increased substantially.

The strategy seemingly worked. Indians were able to leverage their newfound credentials in the form of a mass exodus from the island:

The exit option produced an exodus of tertiary-trained Indo-Fijians – descendants of Indian immigrants of a century ago who were very similar on socioeconomic observables to the Indigenous population – following two coups d’état of 1987. The net counterintuitive effect was to increase the stock of tertiary education inside Fiji. That is, the option for skilled emigration induced mass skill creation amongst the Indo-Fijians that more than offset the skill depletion mechanically caused by emigration…. [I]nvestment into human capital increased for the very half of the population that suddenly faced lower prospective returns on human capital at home, and relatively higher returns abroad.

Where does advantage come from?

When we look around, we see huge differences in achievement across groups. Some groups are vastly overrepresented in domains like law, finance, business, science and journalism – while others are hardly represented at all. In addition, we see that such differences are consistent across societies and are maintained over long stretches of time. How did they emerge?

The success of elite groups is often attributed to the value they place on education. But this is rarely a satisfactory explanation (Indo-Fijians and expelled Poles may be exceptions). If all it took to become elite was to place a high value on education, why wouldn’t other groups have copied them? And why would differences have persisted long after the advent of universal education?

The truth is that, in many cases, elite groups are genetically different from the rest of the population. And they got that way through processes of selection, whereby less- and more-elite members were separated, so that over time or in certain places, membership became disproportionately elite. These selection processes have been created endogenously (as in the case of the Jews) and other times imposed exogenously (as in the case of the Egyptian Copts).

How do elite groups form? The answer is often just: selection.

Cremieux Recueil writes about genetics, 'metrics, and demographics. You should follow him on Twitter for the best data-driven threads around.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

Like and comment below.

British taxes have been progressive ever since the Window Tax of 1696. The uniform land tax was implemented in the late-17th century, and the first permanent British income tax was implemented in 1842, but even after its implementation, many didn’t have to pay it due to their low incomes. Clark’s sample includes all persons transported to Tasmania in the period 1804-53 and all those convicted within Tasmania up to 1893, so the minutiae of British tax law is a plausible factor given the time periods in question.

In fact, it provides us with perhaps the earliest example of the Laffer Curve.

Note that, for this effect to appear, parental age had to be controlled for, since it mechanically reduces the birth order effect. Adjusting for this reduces this confounding. This is a credible adjustment that is explained in the study and its citations.