A Modest Proposal To Turn Canada Into a Narco State

Americans want cheap drugs and Canadians wants loads of money. I smell a deal.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than two hours to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

I have an idea to fix two problems at once, in the process mend a damaged friendship, promote prosperity for all, and make the world a happier, healthier place. That idea is to turn Canada into America’s pharmacy, to make a modern, Canadian pharma-state.1

Trump’s Pricing Plan

The Trump administration wants to lower pharmaceutical prices in several ways, from cutting out middlemen and promoting price transparency, to deregulating in ways that allow cost-cutting, but primarily through Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) pricing.

MFN is a form of reference pricing. The way this works is by capping the prices of drugs sold in the U.S. at the lowest price paid by a comparator nation like Canada, France, or the U.K.—members of the reference class. This approach has been adopted by many countries, and it does lead to lower prices, but those lower prices come at a major cost.

One of the costs of MFN is delays in introducing new drugs across countries. Within Europe, reference pricing leads to delays for poorer countries. The reason for this is that drug companies don’t want richer countries—who can pay more for their drugs—to have the option of poorer references. An added effect of this is that pharmaceutical companies raise prices in potential reference companies, so that their prices can’t be lowered in richer ones. The resulting impairments to the ability to engage in price discrimination make for lower global drug availability and lower global welfare.

If that’s not compelling enough to you, then consider what happened when Medicaid adopted reference pricing in 1991. The result was that Americans tended to face higher prices, because generic drug-producing firms raised their prices due to MFN’s price competition-limiting effects. One could avoid this particular issue by only applying MFN to brand name drugs without a generic counterpart. But think two steps ahead and you’ll notice that doing that reduces the incentives to ever start producing a generic version of drugs in the first place.

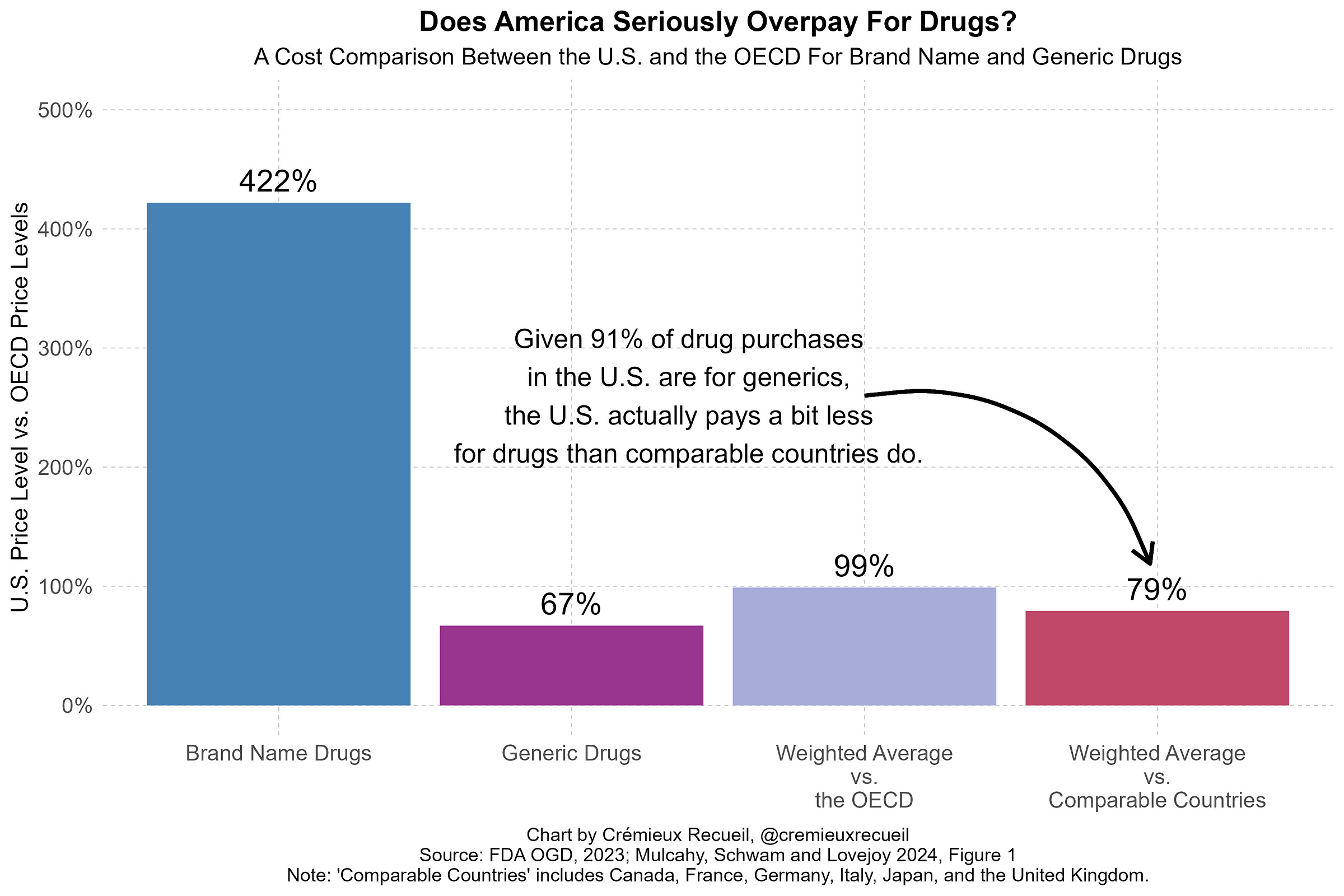

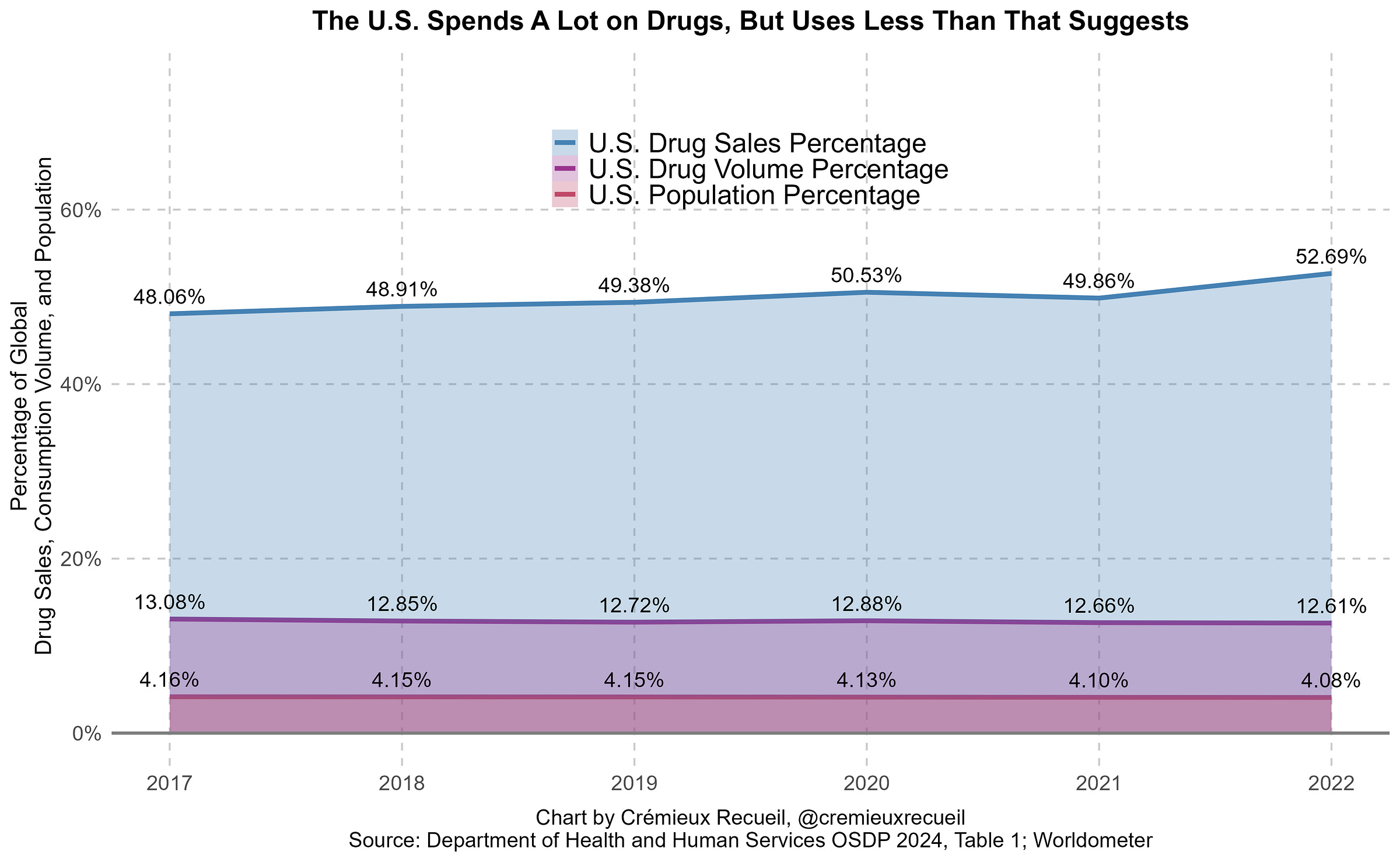

Doing a branded-only-no-generic MFN is almost-certainly bad for prices on net for three main reasons. The first is that America has wonderful generic drug prices.2 In fact, America’s volume-weighted price level is generally better than the price level in other developed countries because America buys so many low-price generic drugs.3

The second is that MFN is unlikely to be able to deliver large brand name drug cost reductions in any case. The best estimates of what MFN can do in practice come from a recent preprint on the subject. The short answer to the question of what MFN can deliver is: nowhere near the price reduction we expect from the introduction of generic drugs.

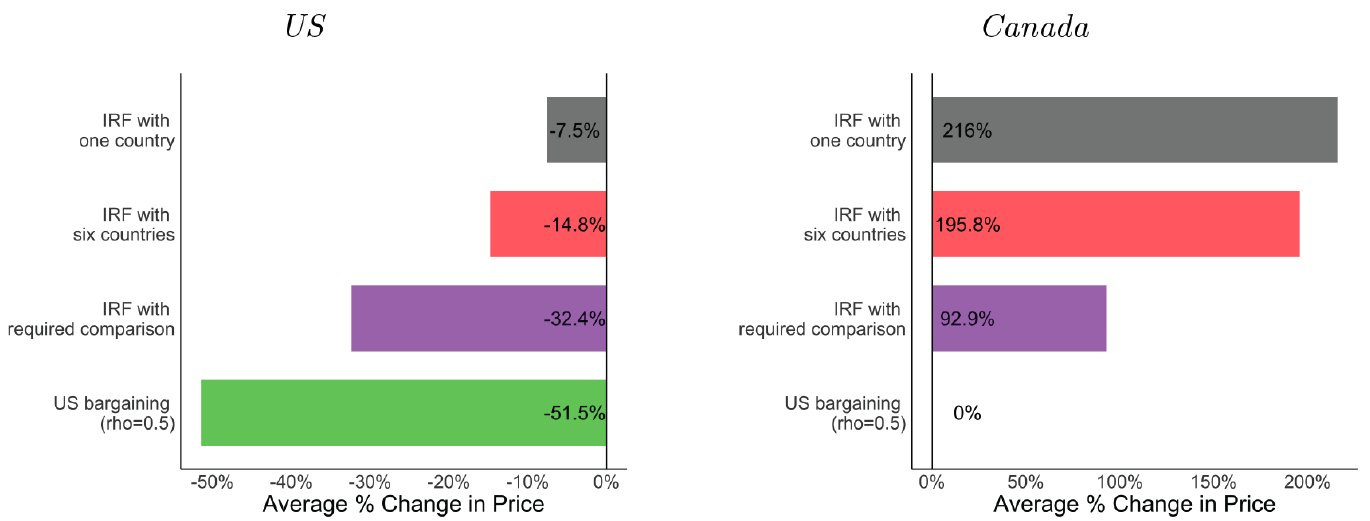

The paper models international reference pricing (abbreviated IRF) in three different scenarios. The first is an IRF with just one country—Canada. The second is one where the U.S. can use six different countries as its reference.4 The third is the same, but the U.S. also compels pharmaceutical companies to keep operating in peer countries, so they’re maintained as a reference. Each of these scenarios is compared with bargaining, where the U.S. starts using its buying power to force manufacturers to lower their prices like other countries regularly do. Take a look at what this does to prices:

In the extreme setting of MFN with compelled market presence, America only achieves a one-third reduction in prices, while prices in neighboring Canada double. You might look at this and think “Good! I hate Canada!” but hold off on that thought. Canada is, after all, America’s culturally and geographically closest ally, and the Founding Fathers wanted Canada to have the right to become part of America whenever it wished to. Canada is a natural friend to America; spiting them does the U.S. no good.

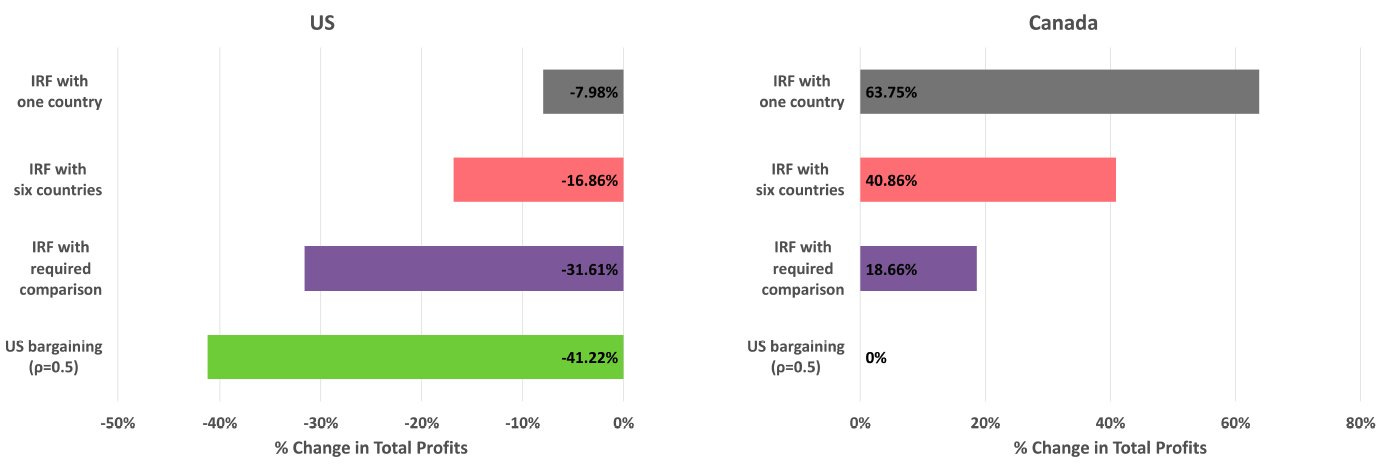

Even if you don’t care about being neighborly, then you should care about the other effects of this policy; namely, falling pharmaceutical profits.

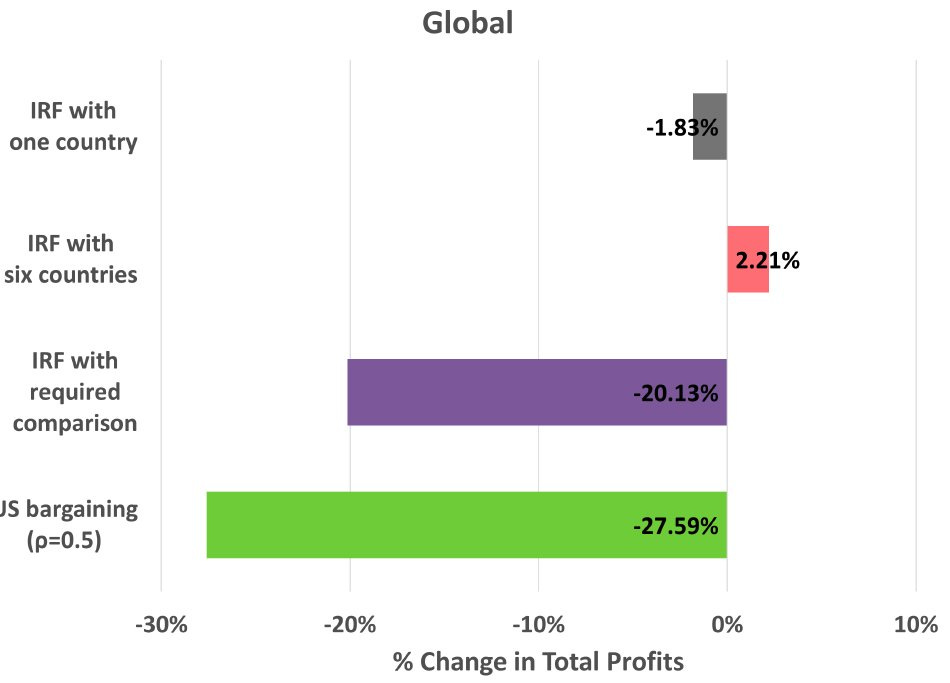

With price reductions in the U.S. and consumption volumes falling even more elsewhere, corporate profits would almost-certainly decline under MFN. In the pharmaceutical industry, that’s devastating generally and especially so right now, because the IRRs are already abysmal. Any additional pressure from the style of MFN that’s probable in practice would likely destroy them.

In the scenarios described above, profits from comparison countries increase, helping to compensate for profits lost in the U.S.

These internationally increased profits could mean that other countries ‘pay their fair share’, as it were. If that happened, the effects on global R&D might be fine. But that’s not very likely. Two of these scenarios result in profits being merely maintained, with all the added inefficiency and global welfare problems of this pricing scheme. But they are not realistic scenarios, because other countries will respond—they won’t sit around while the U.S. starts blowing up their prices. The dynamic effect of MFN pricing on profits is very likely to be globally bad, even with generous assumptions.

This brings me to the third point, which is that MFN runs counter to some of the Trump administration’s other goals. The administration wants pharmaceutical manufacturing done in the U.S. Not feasible with ruined profit margins. They want R&D to not fall apart while prices go down. Not reasonable even if other countries decide to increase public R&D funding, since that funding will not be distributed via market mechanisms, but instead by less reliable bureaucratic fiat. They want R&D done in the U.S. rather than China. Again, not feasible with ruined profit margins.

There would have to be major and unexpected compensating factors for MFN to not destroy America’s pharmaceutical research productivity, with the end result being that much of it simply moves to China. In fact, pharmaceutical research is already heading to China. Any factor like MFN that increases uncertainty and incentivizes corporate cost-cutting by relocating there and licensing R&D from there instead of doing R&D in the U.S., will probably do exactly that.

In other words, America should look elsewhere to fix drug prices. Why not north?

Canada’s Poverty Problem

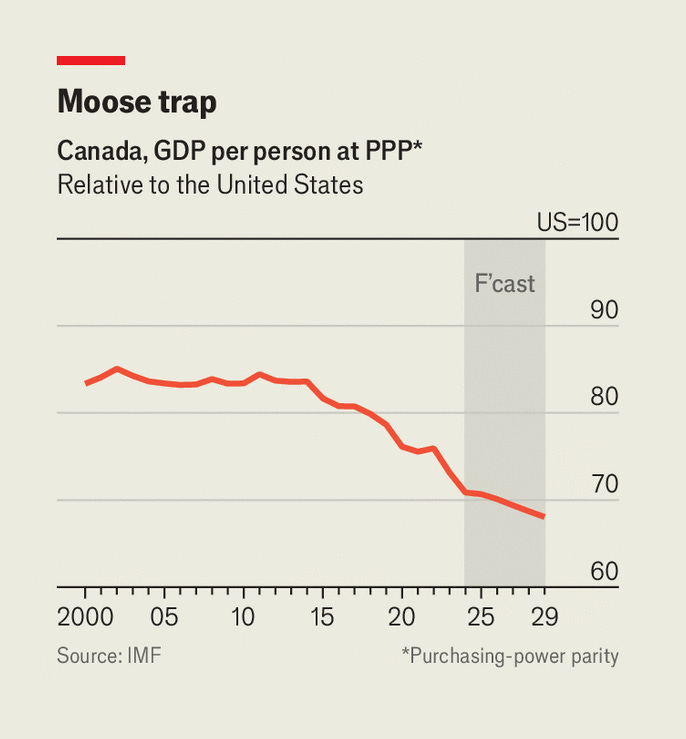

Justin Trudeau’s reign tanked Canadian economic performance. For most of Canada’s history, it was not that much poorer than the U.S. Under Trudeau, that changed. Canada went from being slightly richer than Montana—America’s ninth-poorest state—in 2019, to being poorer than Alabama—the fourth-poorest state—by 2024.

Whatever policies Trudeau decided or failed to decide for Canada did not work, and the country has gone from America’s sibling who’s doing fine enough to being America’s sibling who’s asking for a loan.

At one point in time, Canada was protected from mismanagement by its natural resource endowments—namely, oil—but that’s no longer the world we live in. As the globe transitions further and further from fossil fuels, the protection they’ve afforded Canada will become even weaker. So it’s time: Canada needs a new ‘thing’ to keep it afloat despite all its political dysfunction. That thing can be pharmaceuticals.

How the FDA Can Fix Both Problems

You might be wondering how this plan could work. After all, Canadian companies can’t just sell Americans their drugs. If they want to sell some drug in America, they have to go through the American approval process. Doing that is expensive and potentially not possible due to intellectual property issues. That is to say, if a drug is still under patent in America but not Canada, Canadian companies will be turned away if they ask the FDA to let them sell it anyway.

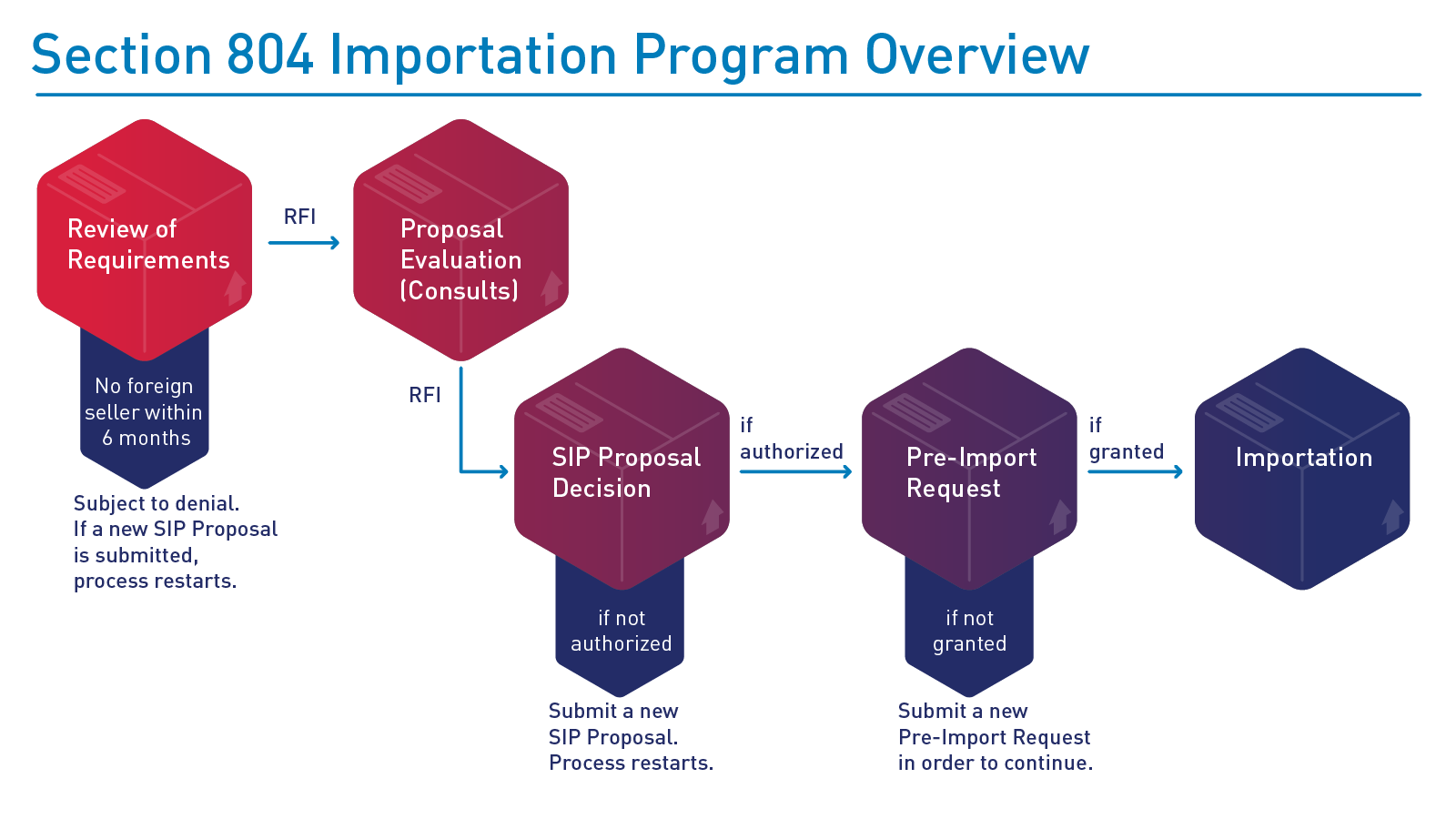

The way around this issue is through a special program that, I’ll argue, is currently extremely underused. That program is the FDA’s Section 804 Importation Program.

The Section 804 Importation Program, or SIP, was borne out of a snippet in a late Clinton-era appropriations bill, which was eventually developed into the modern program in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. The program allows for American states and Indian Tribes to import drugs from Canada for resale, provided they’re also approved for marketing in the United States and they can save the applicant entities significant sums of money.

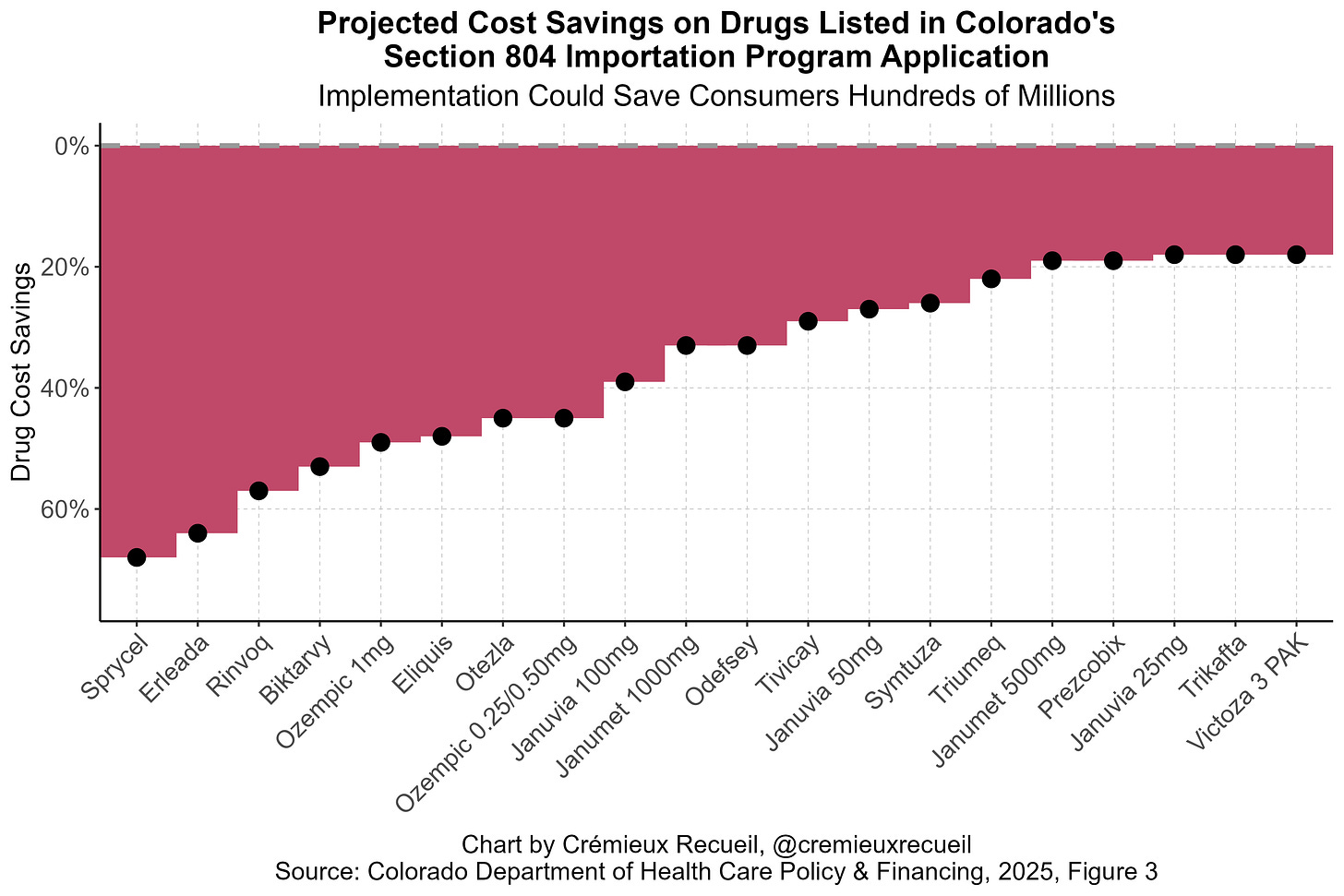

This program essentially allows for importing Canadian drugs to take advantage of the fact that they’re cheaper in Canada. Where this has been proposed, the savings are often considerable. Consider, for example, Colorado’s projected savings for a few drugs listed in their SIP application:

Other states have made similar projections and the numbers are realistic: this program offers clear cost savings for many different drugs, from EpiPens to Ozempic.

But, though these cost savings are clear, are they meaningful? The intuitive answer is “Yes, of course”, because the savings shown above are obviously large in some cases. Lower drug prices would benefit many consumers, right? Unfortunately, the unintuitive answer that I now believe to be right is “No”, because SIP is insufficiently broad, and there are numerous barriers to its use. Notice: the drugs listed above are all that Colorado has settled on asking to import, hence the subtitle’s savings estimate of just a few hundred million dollars, rather than saving consumers the billions that might be available if they had proposed importing a larger basket of drugs.

There are problems with this program that may limit its importance to reducing medical spending by a few hundred million dollars at most. If that’s the case, it’s barely worth it. Let’s go through some of these.

The first and most obvious problem with the program is that Canada hates it. Canada views it as a threat to their drug supply, and rightly so! The program buys drugs sold in Canada and resells them to Americans. It could easily lead to shortages for Canadians. That’s not mutually-beneficial, so Canada has noted that they will step in if the program causes them any issues.

The second problem is less obvious and has to do with regulatory minutiae. I’m referring now to some ambiguity in how eligible drugs are defined for the purposes of the program. 21 CFR § 251.2 defines eligible prescription drugs as those that meet the conditions in an FDA-approved New Drug Application (NDA) or Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA; this is the application used for generic drugs), including “equipment, and facilities”. The point about facilities is crucial. Since the SIP has never been used, and all existing applications are milquetoast, we don’t know if this statute is actually saying that the drugs that the SIP imports must be manufactured at exactly the locations listed in the original NDAs/ANDAs. Moreover, we don’t know if the statute is saying that the facility details must match potentially secret details contained in NDAs/ANDAs and never made public.

If either is the case, then the utility of the SIP is extraordinarily limited, and it’s effectively no better than a somewhat adversarial program that makes Canadians upset while saving Americans a few pennies. The most that can be garnered from this program under this narrow interpretation is an opportunity to say that manufacturers are hypocrites because they don’t want people to be able to reimport their drugs at lower prices—effectively proof that they know they’re ‘ripping Americans off’.

A Mutually Beneficial SIP Redesign

To realize the full potential of the SIP—allowing Americans to access cheap Canadian-produced brand name and generic drugs—we either need (A) a courageous judge who will interpret the law favorably, where manufacturers need only verifiably produce certain drugs that the FDA has already approved in some form, or (B) Congressional action.

Regulators could—and should—get ahead of Congressional action by rewriting the 2020 rule on the SIP. The current rule says pre-import paperwork must show the Canadian drug lot was made in the facilities and on the lines named in the NDA/ANDA. This can be fixed by regulatory fiat. The FDA may delete this section and replace it with a requirement to show compliance with current good manufacturing practices, lot-by-lot chemical testing showing NDA/ANDA-listed specifications are met, and a short supplemental report explaining any process differences. This lets generics made in Canada through the program, so long as they analytically match the U.S. brand.

21 U.S.C. § 384(e)(2)(A) mandates that if an importer does lab work to verify a drug is what it’s supposed to be, the manufacturer must supply the information needed to authenticate the lot of drugs. The large pharmaceutical producer consortium PhRMA hates this and has filed a lawsuit claiming that making them supply this information violates the law and is unconstitutional because it means leaking trade secrets. They’ll probably lose this case if it ever has jurisdiction, but just in case they do some judge shopping, the FDA should preempt them. The FDA can choose to keep letting importers do testing; issue guidance on publicly-available Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls tests so the importer only needs minimal proprietary data to get the job done; or deem the requirement satisfied if the Canadian firm supplies its own certificate of analysis and batch record. The ambiguity in the wording of “supplied by the manufacturer” potentially allows for considering any firm to be the manufacturer, including the one making the imported lot. This probably would hold up in court.

§ 384(h) says that a manufacturer must authorize the use of FDA-approved labeling for imported drugs. PhRMA also says that this is objectionable and says it infringes on their copyrights. If their lawsuit fails, then the FDA can simply wait 30 days and provide importers with the labels, because ignoring the FDA is “deemed consent”. The FDA can also alleviate any labeling-related issues by clarifying that deemed consent applies when a manufacturer is not the NDA holder, and by further allowing importers to strip proprietary names and logos then use the rest of the text from a branded drug verbatim, as domestic generics do. There’s a deemed consent escape hatch from not being able to sell drugs that domestic manufacturers refuse to provide labels for, and that’s great. The FDA should acknowledge that and provide appropriate guidance for it.

The net effect of doing this would be three-fold:

Canadian generics would become regulatorily eligible and the facility-match hurdle would disappear.

Importers can rely on their own testing plus batch data from Canadian firms, without touching U.S. brand holder trade secrets, obviating another lawsuit risk.

Labeling hurdles for the program shrink thanks to the 30-day ‘silence = consent’ supposition and the FDA’s ability to provide permission to remove trademarked content from labels.

But, crucially—and this is what PhRMA would probably sue over—, importers would have to certify that a product is “approved for marketing in the United States”. That could very well mean that a Canadian manufacturer must obtain an ANDA or be written into the drug’s NDA as an alternate manufacturing site. I say “could very well”, because it’s not clear. The wiggle room in the statute remains untested! If it does mean an ANDA or NDA requirement, then all of this regulatory change amounts to nothing. Alternatively, if it does not, then that means we live in the sensible world where a drug that’s identical to another drug is deemed to be resalable as if it is that drug—which it is. But just in case this fails in court…

Congress should go ahead and amend § 384(c)(1), which says every imported lot must comply with section 355 of the Act, thus potentially tying them to exact facilities named in NDAs/ANDAs. They can do this by inserting this sentence onto the end, reading: “except that, for a drug imported under this section, the Secretary may deem it to comply with section 355 notwithstanding manufacture at a facility not identified in the application, if that facility is registered with Health Canada, meets current good-manufacturing practice, and the importer shows the lot meets all quality and specification requirements in the NDA or ANDA.”

They must then do one more thing, which is to strike § 384(h). This currently requires manufacturers to provide importers with written authorization to use approved labeling. They can replace this with “The importer shall submit, and the Secretary may approve, labeling that is substantively the same as the FDA-approved labeling except for proprietary names, logos, or other trademarked matter.”

If Congress made just these two changes, there would be no need for regulatory changes, because the SIP would simply function as a lever to lower costs and build friendship with Canada.

How could they do this? The big issue there is that PhRMA lobbies hard, and they put millions in the pockets of Congressmen to great effect. The best way to go about this is, therefore, to be sneaky and to throw these changes into an appropriations rider that no one mentions until it’s passed. I know that’s asking for a lot, but it is a legal method to get things done.5

What About Innovation?

Before getting onto the last section, I want to mention a quibble people have with saving money in healthcare: what about innovation?

There is evidence that more medical spending yields more medical innovations, more new drugs, more new devices, etc. People run too far with this and say that cutting medical spending is evil, genocidal, anti-innovation. This is mostly exaggeration. Though there needs to be some way to reward medical innovation, there is nothing that can justify the current system of indefinite patent protection under flimsy justifications, like that an NDA filing needed to be updated to add another spring to an injector.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers also engage in a variety of corrupt practices, like hiring adversarially to prevent researchers going elsewhere to do research, obtaining patents on things they never intend to produce, and building up unjustifiable and absurd patent thickets.

It’s extremely debatable whether allowing pharmaceutical producers to indefinitely fend off competition through exploiting legal loopholes helps innovation. In fact, I’d argue, it helps to stop innovation, because the incentives to innovate are just not there. Instead, companies (like Novo Nordisk—check the semaglutide thicket) choose to iterate on ways to extend patent protection and stop innovating in meaningful ways, because it’s more difficult and expensive than exploiting the broken IP system.

I’ll contend that Canadian patent terms are more than enough to reward medical innovators. And if they are not, let’s revisit some time down the line. We have a fiscal crisis afoot, and that’s likely to be a bigger issue than modestly lower returns for pharmaceutical manufacturers who’ve more than paid off and profited from products like the EpiPen or Keytruda.

What Does a Realized SIP Mean?

Imagine if America could import cheap, Canadian semaglutide. It could end the obesity crisis right away, saving trillions in the process. Imagine if America could import cheap, Canadian versions of any number of drugs. Their domestic prices would undoubtedly fall, just as prices tend to fall when copy-cat drugs or generics enter the market.

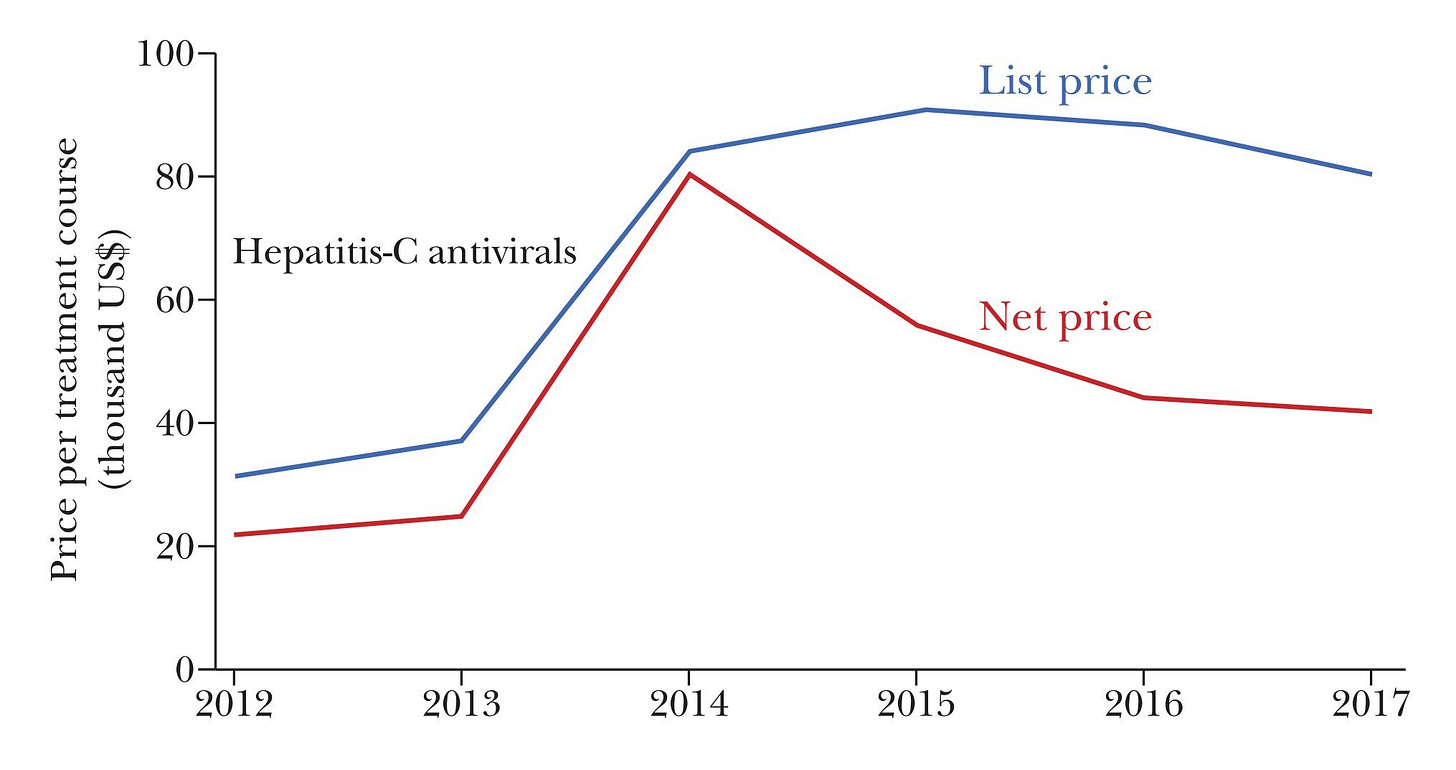

Consider the case of hepatitis-C antivirals. Gilead’s 2014 cure was revolutionary, but it had a huge price tag. After Abbvie released a product that did the same thing in 2015, the price plummeted. This isn’t unusual. The typical price-cutting effect of having just a handful of drugs on the market for a condition is massive.

Now imagine what selling those drugs would mean for poor ole Canada.

America accounts for roughly half of all global drug spending on an ex-manufacturer basis.6 In 2024, that meant about $798 billion in spending. That’s about a third of Canada’s $2.24 trillion 2024 GDP.

A fully realized SIP could easily see Canada gaining tens of billions (and likely more), while saving Americans tens of billions (and likely more) in turn. That shift could leave Canada much like Denmark between mid-2022 and mid-2023. That is, with an economy buoyed by American pharmaceutical demand.

But, you might be thinking, would Canada want that? As I mentioned earlier, they are against the SIP as it is. But I think in its fully realized form, that would no longer be the case. In fact, they’d be incentivized to invest more in pharmaceutical production to meet American demand, and there’s no doubt with their new-found spending power and production, that they would have fewer issues of their own with drug shortages and losing out to Americans’ comparatively greater spending power. And who knows—maybe turning Canada into America’s drugstore will end all the tariff angst and lower the odds of a repeat.

The title of this article is “Narco State”. I used that for the association with drugs. I find it more humorous than “Pharma State”.

American generic drug approvals are very powerful tools for affecting price changes. As an example, they have successfully disrupted price-fixing cartels.

When I presented this fact, some people said that it was wrong because America’s prescription drug spending needs to be weighted by branded versus generic spending instead of branded versus generic consumption volumes. This is a confused view because it double counts spending and produces an index that simply acts as a proxy for the averaged price level without respect for the amount of consumption of either the branded or generic categories. Taken seriously, it means that America having cheaper either branded or generic drugs alone could practically never appear to fix its spending problem, which is illogical.

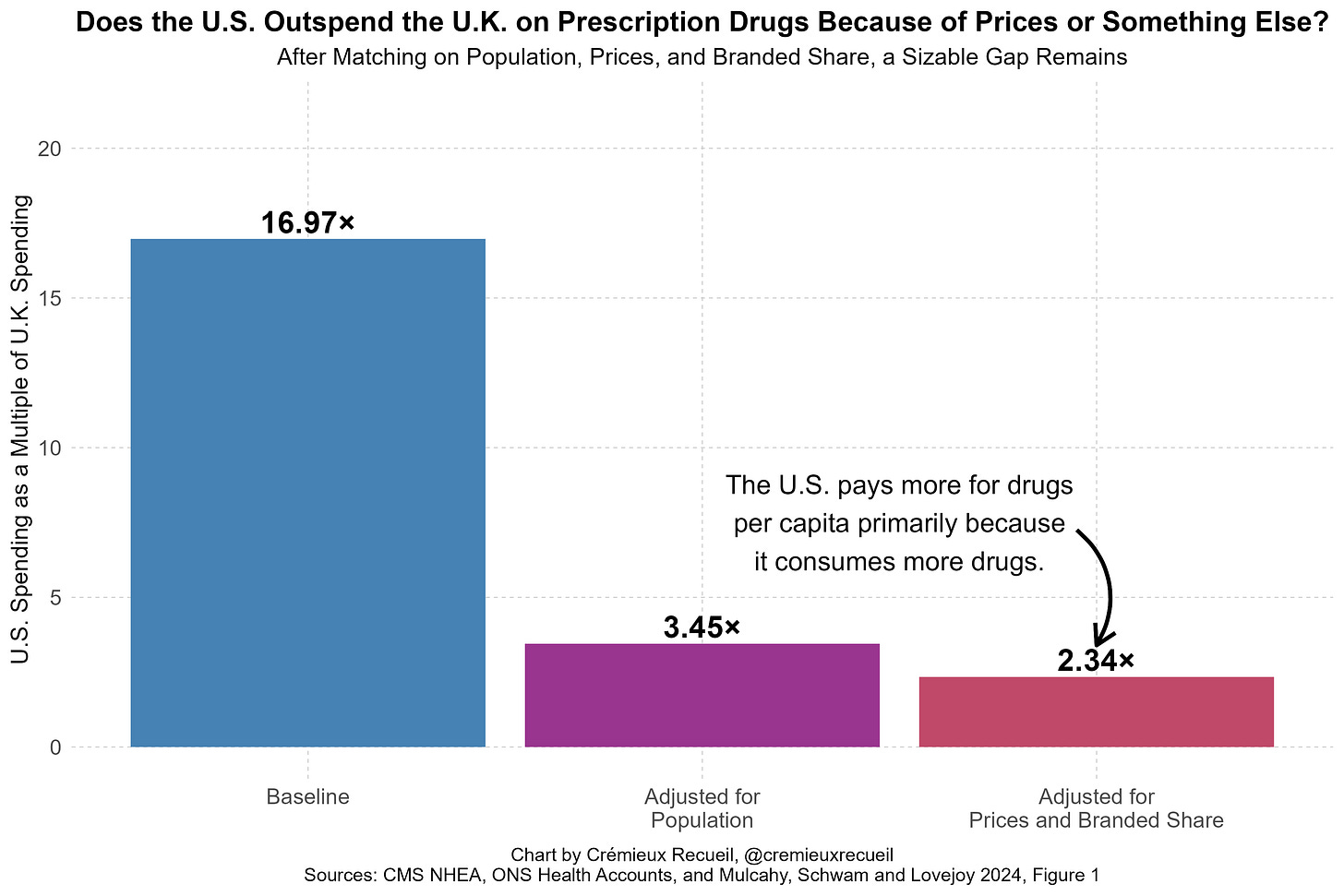

You can see that this suggestion is absurd by simply comparing the U.S. and a country like U.K. and adjusting away the effects of paying more for branded drugs. Most of the prescription drug spending gap remains because America’s overall drug spending issue is about volume, not prices. That is, Americans consume more; higher prices are a secondary concern when it comes to total prescription drug spending.

And as an aside, the U.S. should never use a poor country as its reference, as this would be a humanitarian disaster and undoubtedly tank pharmaceutical profitability for many drugs.

Reconciliation could also do the job. Under the Byrd Rule, a reconciliation provision must have budgetary effects that are not “merely incidental” to the policy change. The CBO would have to show that allowing Canadian generics lowers federal outlays enough to satisfy the parliamentarian. I think this is trivial. But even then, any extraneous policy language like trademark carve-outs could be stripped by a Byrd Rule point of order, requiring 60 votes to waive. So if the reconciliation route was pursued, they could change § 384(c)(1) and leave the rest to regulators, achieving the same end result we wanted.

After rebates and discounts (i.e., using net prices), U.S. medicine spending falls by almost 40%, leaving it responsible for well under half of global medicine spending.