Are the Rich Antisocial and the Poor Emotionally Intelligent?

Is caring too much the curse of the working classes?

Working-class people may be, as we're ceaselessly reminded, less meticulous about matters of law and propriety than their "betters", but they're also much less self-obsessed. They care more about their friends, families and communities. In aggregate, at least, they're just fundamentally nicer. — David Graeber, 2014

Is the above quotation true? When Graeber made those remarks a decade ago, he showed he was at least aware of some behavioral evidence against it in the form of poor people being disproportionately involved in crime and matters of impropriety (e.g., public indecency, alcoholism, substance abuse, vagrancy, public disturbances, and otherwise being a nuisance, a cad, a blaggard, and/or someone’s unwanted ward). Certainly the most objective indication of the disturbing nature of the poor is their disproportionate involvement in crime. However, many argue that involvement in crime isn’t their fault, as it’s only a natural consequence of a life of material deprivation. We now have excellent evidence against that view,1 but—as Graeber noted—there’s psychological evidence that “Those born to working-class families,” like Graeber himself, “invariably score far better on tests of gauging others’ feelings than scions of the rich, or professional classes.”

“After all,” we’re told, “this is what being ‘powerful’ is largely about: not having to pay a lot of attention to what those around one are thinking and feeling. The powerful employ others to do that for them.” Graeber’s allegation is that the rich, for want of capability, employ the “children of the working class” to do their emotional labors for them.

Beyond the argument not making sense, a glaring problem for Graeber’s narrative is that I happened to read his citations. I know that’s taboo in certain circles, but bear with me, because I’d like to show you what I’ve found.

Empathic Accuracy and Flashy Cars

One of the two papers Graeber cited was by Kraus, Cote and Keltner. It was a set of three studies comparing lower-class and upper-class people in terms of things like their empathic accuracy, the ability to make accurate inferences about emotion from static images of people’s eyes in motion, and the ability to judge another person’s emotions live.

The first study involved 200 full-time university employees and it was observed that participants with high school educations were better able to identify emotions in photographs of human faces (p = 0.02). This finding was robust to gender and education being included as covariates (p = 0.02). Thus, “lower-class individuals have greater empathic accuracy than upper-class individuals.”

The second study provided similar results based on 196 university students, with participants’ subjective social class being negatively related to the empathic accuracy. In this study, empathic accuracy was based on participants rating their own emotions and estimating the emotions of a partner during a hypothetical job interview. Subjective social class, treated continuously, was negatively correlated with performance (p = 0.04), and the result held up with controls for sex and emotional expressivity (p = 0.01). The authors did note that, the direct effect of subjective social class on empathic accuracy was not supported, as—they claimed—it was mediated by the tendency to engage in contextual explanation among the lower-class. The indirect effect of subjective social class via that tendency was significant (p = 0.04).

The third study involved 81 university students and a subjective social class manipulation. The manipulation was written out as follows, with the upper-class and lower-class positions differentiated in brackets:

Now, please compare yourself to the people at the very bottom [top] of the ladder. These are people who are the worst [best] off—those who have the least [most] money, least [most] education, and the least [most] respected jobs. In particular, we’d like you to think about how you are different from these people in terms of your own income, educational history, and job status. Where would you place yourself on this ladder relative to these people at the very bottom [top]?

By placing themselves relative to those doing very well or very poorly, participants were being ‘primed’ to think of themselves in the opposite way. After this, they performed the famous “Mind in the Eyes” task and, whaddya know, those who were in the upper-class condition performed worse than those in the lower-class condition (p = 0.03). With sex and agreeableness as covariates, this result held up (p = 0.04).

In presenting these results, I have shown all of the primary tests’ p-values, but not their magnitudes. In some cases, the magnitudes were large, but—critically—they were always just-significant. The p-values were all barely under the threshold for significance in the field the paper came from and never once did the authors correct for multiple comparisons. Beyond the evidence for p-hacking, these papers have all of the hallmarks of papers hit by the replication crisis: insufficient summary statistics, ‘priming’, university student and staff samples, and—with respect to Graeber’s inferences—a design that seems only tenuously relevant.

The second paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science by Piff et al., and it comes with a very forceful title: Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Given the aforementioned reality that poverty and crime are related, the title is provocative—what sorts of ‘unethical’ behavior might the rich be getting up to without getting in trouble?

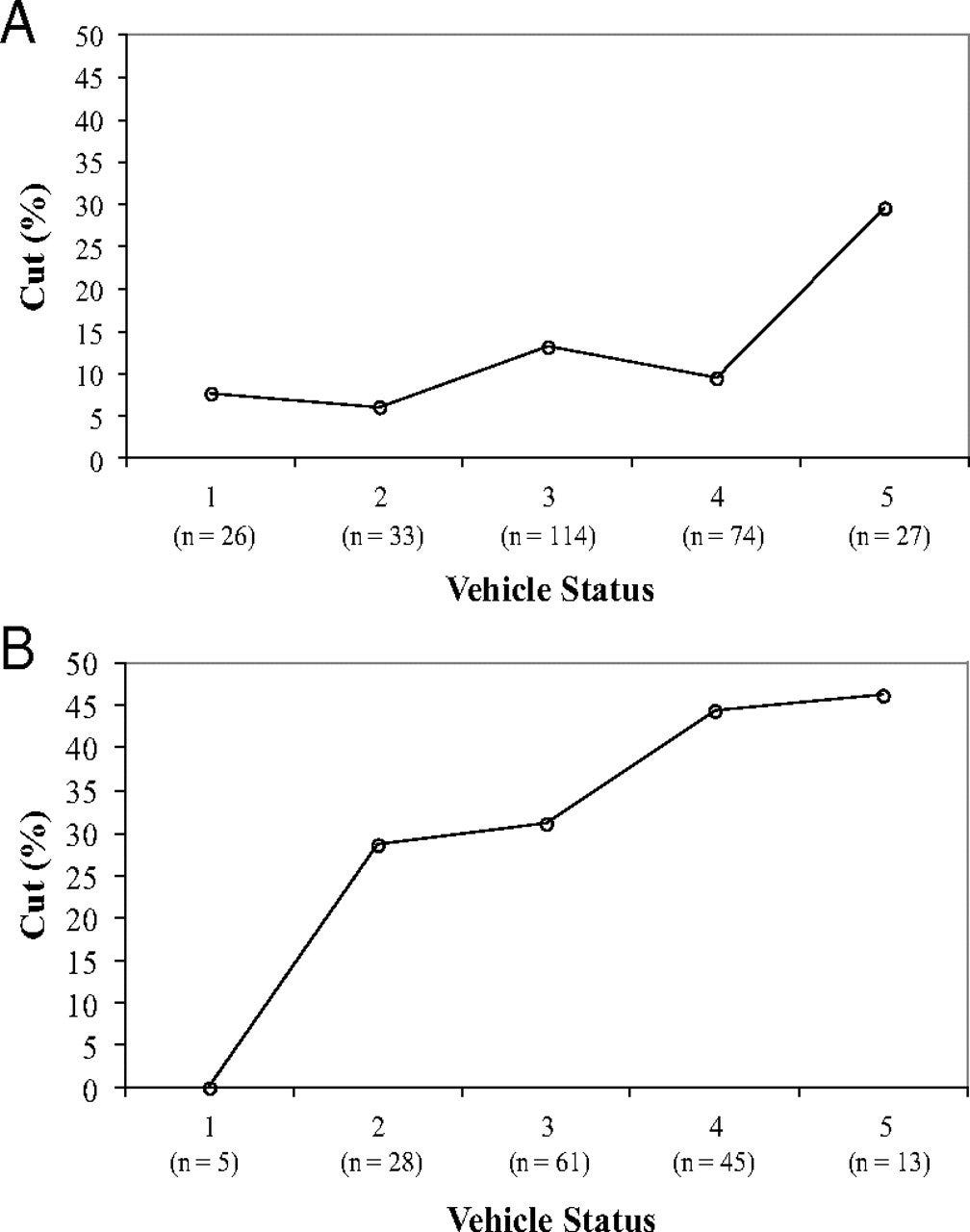

The paper’s first two studies were naturalistic: students watched four-way intersections and concluded that “upper-class” cars were less likely to wait their turn, cutting off other vehicles (A) or pedestrians (B) in the process. The effect in these studies was decidedly nonlinear for the cutting off other vehicles, and the point estimates for the second study are obviously not credible given how few cars were classified in the most extreme class bins. And for that matter, what in the world is an upper-class car? The authors leave that unknown: they’re whatever student raters said they were. P-values? 0.046 and 0.040.

In the third study, participants “read eight different scenarios that implicated an actor in unrightfully taking or benefiting from something, and reported the likelihood that they would engage in the behavior described.” They reported their subjective social class as well and—allegedly—as “hypothesized, [subjective] social class positively predicted unethical decision-making tendencies.” (p = 0.043, reported as “P < 0.04”).

In the fourth study, they replicated the priming paradigm Kraus, Cote and Keltner used in their third study, and they found that significantly more of those in the upper-class rank condition would take candy from counterfactual children (p = 0.002—marvelously significant!), and they engaged in more unethical decision-making otherwise too (p = 0.02).

In the fifth study… subjective social class, telling job candidates truthful statements about the job they’re interviewing for being eliminated soon, p’s = 0.02, and being favorable towards greed, p = 0.001. Sixth study, same social class measure, participants were given prizes based on high dice rolls but the dice were rigged to sum up to twelve and reports exceeding twelve indexed cheating, p = 0.049, being favorable towards greed, p = 0.03. Seventh study, priming people to feel greedy, finding that subjective social class differences in unethical behavior (p = 0.049) and related to the greed prime (p = 0.032) held up, that in the neutral condition, the high-class group was more unethical (p = 0.047) and in the primed condition, the differences were nonsignificant (p = 0.16, reported as “P = 0.17” with a directionally consistent effect), because there was a significant social class by condition interaction (p = 0.03).

You’ll notice I phoned in the descriptions near the end. My reason is simple: it is a waste of everyone’s time to think about these studies. They were not good! They were small and underpowered and the authors made conclusions based on their lack of power, they were obviously p-hacked, they were implausible, their measures were bad, their samples were not population-representative, and, in a few words, they were little more than mind-polluting, politics-justifying rubbish.

Who’s Really Unethical?

Large-scale, representatively sampled tests of the effect of social class—real social class, not just subjectively-felt social class—on prosocial behavior came out in the year following Graeber’s article. With these tests in hand, we can see if Graeber was right, if there is a reason to think “the ultimate bourgeois virtue is thrift, and the ultimate working-class virtue is solidarity.”

Korndörfer, Egloff, and Schmukle (say that five times fast; henceforth, they’ll just be “KES”) start off their paper with an important note that, if true, Graeber should have known:

Recent social psychological research has presented evidence of a negative effect of social class on several prosocial behaviors. In these studies, higher class individuals were found to be less charitable, less trusting, less generous, and less helpful than lower social class individuals. These findings have been implemented in a social-cognitive perspective on social class, have been used as a paragon for a newly developed psychological decision-making process of prosociality, and have been eagerly picked up by the lay press.

However, there are important reasons to question the proposed negative relation. On the one hand, research outside the field of psychology has not been in line with this psychological perspective. On the other hand, some methodological weaknesses in this psychological research lower its generalizability and conclusiveness.

This context is nice. It tells us that what Graeber was citing as widely accepted was really the work from one field: social psychology. Today, social psychology is a field widely considered—alongside nutrition—to be the most impacted in the replication crisis. If we believe social psychology is worse than other fields, we should, thus, work from a prior that the findings Graeber didn’t cite were probably better than the ones he did. The fact that his cited findings were directionally what you might want if you’re someone with progressive politics makes things worse.

KES proposed revisiting these findings with large, population-representative, international datasets that contain objective measures of social class and diverse measures of prosociality. In terms of datasets, they used the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), the American General Social Survey (GSS) and Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX), and the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP).

These datasets are pretty great. The SOEP surveyed more than 10,000 randomly-selected German households containing nearly 23,000 people, and has been surveilling since 1984. The CEX is gathered by the U.S. Department of Labor and is a quarterly interview series the government uses to produce official statistics, from which KES drew data on over 32,000 households surveyed between 2005 and 2012. The GSS is an annual cross-section of American life, with thousands of persons involved each wave, from which the authors drew the data for nearly 4,000. The ISSP involves surveys in more than thirty different countries, from which the authors drew data for more than 37,000 people. Any one of these datasets dwarfs the combined size of the data from the studies Graeber cited.

The first thing KES checked was for something they believed might be a methodological artefact: Some of the social psychological work on this topic had indicated a U-shaped relationship between the relative amount of money people donated and their social class. In other words, the poorest and the richest donate the largest parts of their incomes, even if the rich—by virtue of being rich—donated absolutely more. KES noted that this could simply be an artefact of looking at only those households that donated. If donation probability was related to social class, that could inflate the appearances of lower-class homes’ donation habits.

In the SOEP and the CEX, objectively-measured social class (i.e., things like income, education, occupational prestige, etc.) were positively-related to the probability of donating at all, confirming KES’ suspicion about a possible source of the artefact.

From the GSS, KES had access to both objective and subjective measures of social class, so they could compare those. In doing so, they found that objective social class was a stronger predictor of donations than subjective social class, which—as a reminder—much of the prior literature was based on.2

In terms of odds ratios, the probability of donating related to social class like so:

The artefactual nature of the curvilinear relationship between amount of donation and social class was confirmed: looking only among donating households, the poor did donate relatively more. But, we must remember: they tended to donate far less often.

The GSS did not contain data on the relative amounts of donations, but it did contain data on the frequency of donation, allowing us to square this circle if that quantity monotonically increases since the “relatively large” donations by the poor who choose to donate would be more likely to be one-offs. That was the case.

This line of evidence on donations might not be totally convincing, since lower-class persons have to operate under much tighter material constraints than the rich. In all likelihood, they’ve had to do so for longer as well, so they could have had it dinned into them not to give, for fear that they might not be able to in the future—neither a point for or against Graeber.3

The next thing to look at was volunteering behaviors.

The lower-class tend to have more free time, to spend relatively more time on leisure activities, are more likely to use welfare and less likely to have a recorded job or a full-time job if they’re employed at all, and they take longer to do things we all have to do. They have no non-sociological excuse not to volunteer more.4 On the other hand, if the upper-class volunteer more, they would be doing so in spite of being gainfully employed more often and just generally having less free time for helping others.

In the SOEP, the upper-class volunteer more often and at higher frequencies.

In the GSS, the upper-class volunteer more and at greater frequencies, when stratified by either objective or subjective social class.

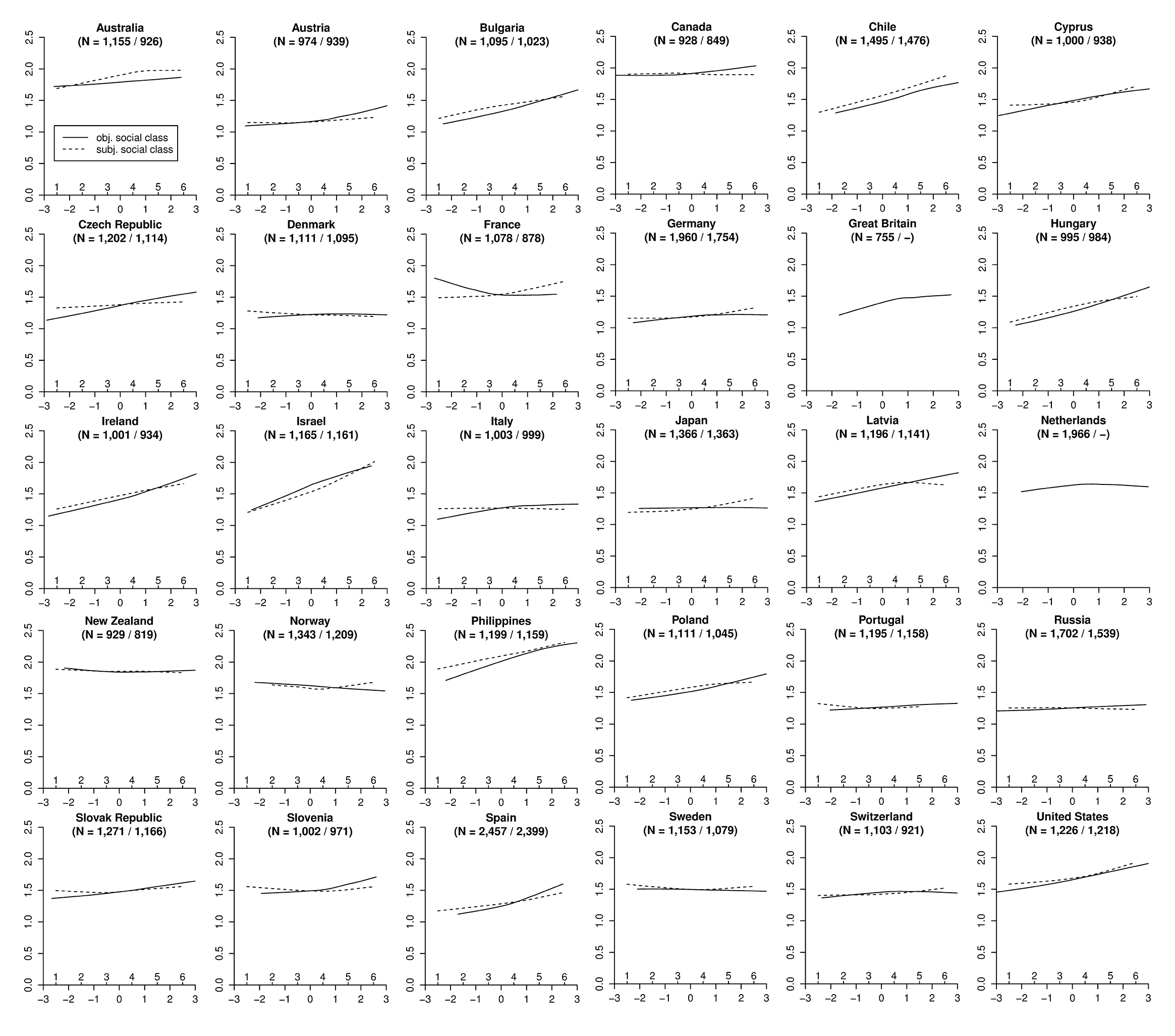

Across all 31 countries featured in the ISSP, objective and subjective social class were associated with 18% and 15% greater odds of volunteering at all, and meaningfully higher frequencies of volunteering. The relationship between the frequency of volunteering and social class was generally positive across countries, but it was a bit less clear-cut:

Looking back at the GSS, respondents were asked about a different type of volunteering: “Everyday helping”. This is a form of giving defined by respondents having, in the last twelve months: “(a) given food or money to a homeless person, (b) returned money to a cashier after receiving too much change, (c) allowed a stranger to go ahead of them in line, (d) offered their seat on a bus or in a public place to a stranger who was standing, (e) looked after people’s plants, mail, or pets while they were away, (f) carried a stranger’s belongings, such as groceries, a suitcase, or shopping bag, (g) given directions to a stranger, or (h) let someone they did not know well borrow an item of some value such as dishes or tools.”

There was a non-monotonic relationship for this scale, such that people did less everyday helping if they were poor, but not much more if they were richer. Though this fits with the rest of the datapoints presented so far, one could much more easily argue that this has something to do with capability than they could for volunteering more generally.5

The evidence on volunteering is much less ambiguous and much less legitimately contestable, so therein lies a point against Graeber’s original thesis. But, one could still argue something about material constraints on the ability to volunteer and an audience might stick with their point. So, here’s a resolution in the form of a game.

In the SOEP, participants played the trust game. In this version of the common game, Players 1 and 2 receive 10 points of seed capital to start:

They were told that they could keep the points for themselves or that they could fully or partially allocate some of their points to the other player. They were further instructed that (a) for each point they kept, they would receive one euro, (b) for each point they allocated to the other player, the other player would receive two euros, and (c) conversely, for each point the other player allocated to them, they would receive two euros themselves. To reduce bystander effects and to maintain the original double-blind design, participants were told to write down their decision on a form and put it in a sealed envelope, which was given to the interviewer. Player 1 was informed that he/she would be the first to make his/her decision. He/she was further told that Player 2 would come to know his/her decision before he/she made his/her decision. In this game, the behavior of Player 1 is therefore interpreted as trust behavior. Player 2 was told how many points Player 1 allocated to him/her. He/she could subsequently decide how many of his/her 10 points he/she wanted to send to Player 1 in return. In the trust game, the behavior of Player 2 is therefore interpreted as trustworthiness.

Unlike a real trust game, the partners were fictional, although the participants were not informed of this fact.

When people went to play, here’s how things turned out: the higher their objective social class, the greater their trust and trustworthiness.

As with donations and volunteering, one could construct some reason why the selfish performance of the lower-class isn’t their fault.6 At the end of the day, that doesn’t matter because selfish is part of who they are, regardless of why. If society imposes on them and makes them more selfish, so be it—they’re still selfish!

As for the rich, once we’ve moved past the narratives about their evils and the low-quality social psychological results levied against them, we can enjoy some certainty that they’re rich in more ways than one. Indeed, it seems the rich are also rich at heart.

And the crime issue mainly has to do with impassioned acts of violent crime, but why let a fact like that get in the way of Graeber’s nice story?

This difference in predictor strength could be influenced by the greater granularity in objective as opposed to subjective social class. The difference shouldn’t be very large though.

Notably, if the poor were just equally generous to start and they hadn’t had something pushing down their probabilities of doing things like donating and volunteering, we should expect them to donate more for reasons like that, among the rich, support for redistribution falls being around the poor, and among the poor, it increases. On a similar note, there is a study that suggests those rich who grew up poor are, in various ways, less sympathetic to the poor than those rich who grew up rich.

Besides higher rates of obesity and other disability, which analyses can easily be adjusted to account for.

This makes sense given that this form of volunteering doesn’t mesh with results about volunteering more generally.

Perhaps more interestingly, by downloading and analyzing the publicly-available data with a single-factor model, it can be seen that linearity is achievable by correcting (liberally given the poor fit) for measurement noninvariance. Perhaps this has to do with the fact that answers were provided by choosing six categories which could differ on an individual basis, and for which the categories that tended to be chosen by the lower-class were different than those picked by the upper-class, rather than that the difference was due to differences in capability shown through honest question answering. Because the items people chose were not totally comparable by social class, noninvariance is unavoidable either way. I’ve said it many times before: finding bias doesn’t tell us why we found bias.

One could, for example, claim that, to the lower-class, the amount of money that they could win by duping other people and being selfish would be more likely to change their life in a positive way, giving them greater incentives to be untrustworthy.

A lot of this seems like it could just be explained by diminishing marginal utility of money and a increased burden of the poor. If we try to isolate properties of the personalities of the kinds of people who are poor vs the kinds of people who are rich, they should be properties that don't apply to two sets of identical populations who were arbitrarily assigned to "ditch digger for 10k a year" vs "interior designer for 300k a year" category. Our ditch diggers would presumably be more fatigued, less able to volunteer, less capable of noble acts of financial self-sacrifice, and so on, even if at a personal level they were all just as nice or even nicer than our interior designers.

As a very crude level we can approximate how pro-social someone is by their propensity to trade their own standard-of-living utils for other people's standard-of-living utils (because they receive feel-good-for-helping utils in return), which is a pointlessly crass way of formalizing "willing to help others at expense of self." But for two people identically willing to make this tradeoff, and thus somehow "morally equivalent", the rich person will be far more able to buy "I was a good person today" utils at $10,000 a piece because it costs them a lot less in standard-of-living utils to do so.

Anecdote: as part of the freshman university hazing in Brazil, I had to beg for money at a traffic light for hours. I was quite surprised to notice a strong correlation where poor cars donated more often than rich cars! Maybe it was mediated by AC on and windows closed, but at that time I was shocked. P.s. It would have been obvious I was a fresher at university rather than a common beggar.