Evaluating a Sitting Senator's Healthcare Claims

If you're a public official who wants to to use numbers, use correct numbers, and if you're going to speculate, try not so speculate wildly, lest you end up telling brazen lies to the American people

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy does not have even a basic understanding of American health statistics.

On December 15th in a video he posted to the social media platform X, he claimed that “thousands of people… die often anonymous deaths every single day in this country at the hands of a healthcare industry that mostly doesn’t give a shit about people and only cares about profits.” He noted that there were exceptions in the form of good people like “nurses, doctors” and he castigated a system that “pad[s] profits and make[s] money for the people who run the biggest companies”, likely referring to UnitedHealthcare and other large health insurers. Quote: “The business model of the healthcare industry is to deny care—necessary medical care to people who need it—and [to] force them into bankruptcy, or worse let them die, in order to grow a profit.”

He says he knows all this, and millions of Americans know it. But they do not “know this” and they cannot “know this” because it is not and cannot be true.

If you know the most basic healthcare statistics for the U.S.—like life expectancies, mortality numbers from different conditions and at different ages, denial rates and reasons and so on—then you realize that Senator Murphy’s is an impossible claim. But in case you don’t, I’ll explain why while being generous to his position and still taking him seriously given the power of his position and the duty holding that position puts on him to do his due diligence before addressing the American people as he did a few days ago.

Firstly, Senator Murphy claims that “thousands of people” die “every single day” due to the denial of care. If we set “thousands” to the minimum it can be, then we get to 730,000 annual deaths due to the denial of care by a system that “only cares about profits”. He was being hyperbolic, but, two things: there are plenty of people who share his exactly-stated view—ignorance is common—, and he’s a Senator, someone who represents millions of Americans, so he should own the things he says. We ought to take him seriously because he is in one of the world’s most important positions.

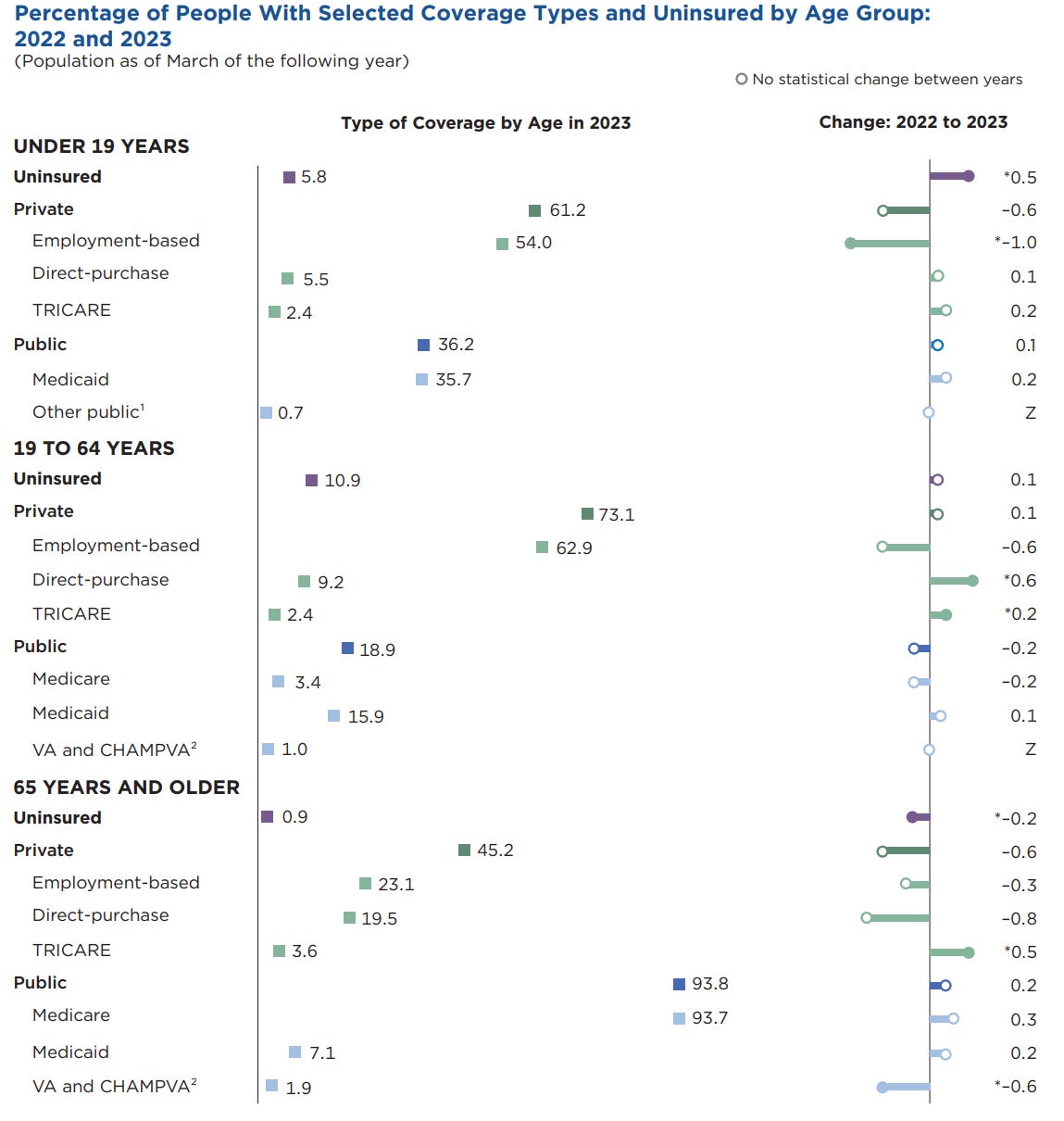

The qualifier he provided, that denial deaths are driven by a system that “only cares about profits”, is critical, because it means that almost all deaths after age 65 do not count. When people turn 65, they qualify for Medicare. Medicare is the reason why virtually everyone over that age is covered. Not only that, but Medicare means that the elderly are covered by a system without a profit motive on the insurer’s part, since the insurer’s role in Medicare is filled by the government.

I am reasonably certain that Senator Murphy does not believe Medicare is a broken system that kills Americans with denials since the fee-for-service (FFS) variant minimally uses prior authorization and Advantage outperforms FFS while operating within strict constraints set by CMS. Senator Murphy is a champion of ‘Medicare-for-All’, so for consistency, we have to cut virtually all deaths over age 65 from the possible deaths that can be attributed to denials.

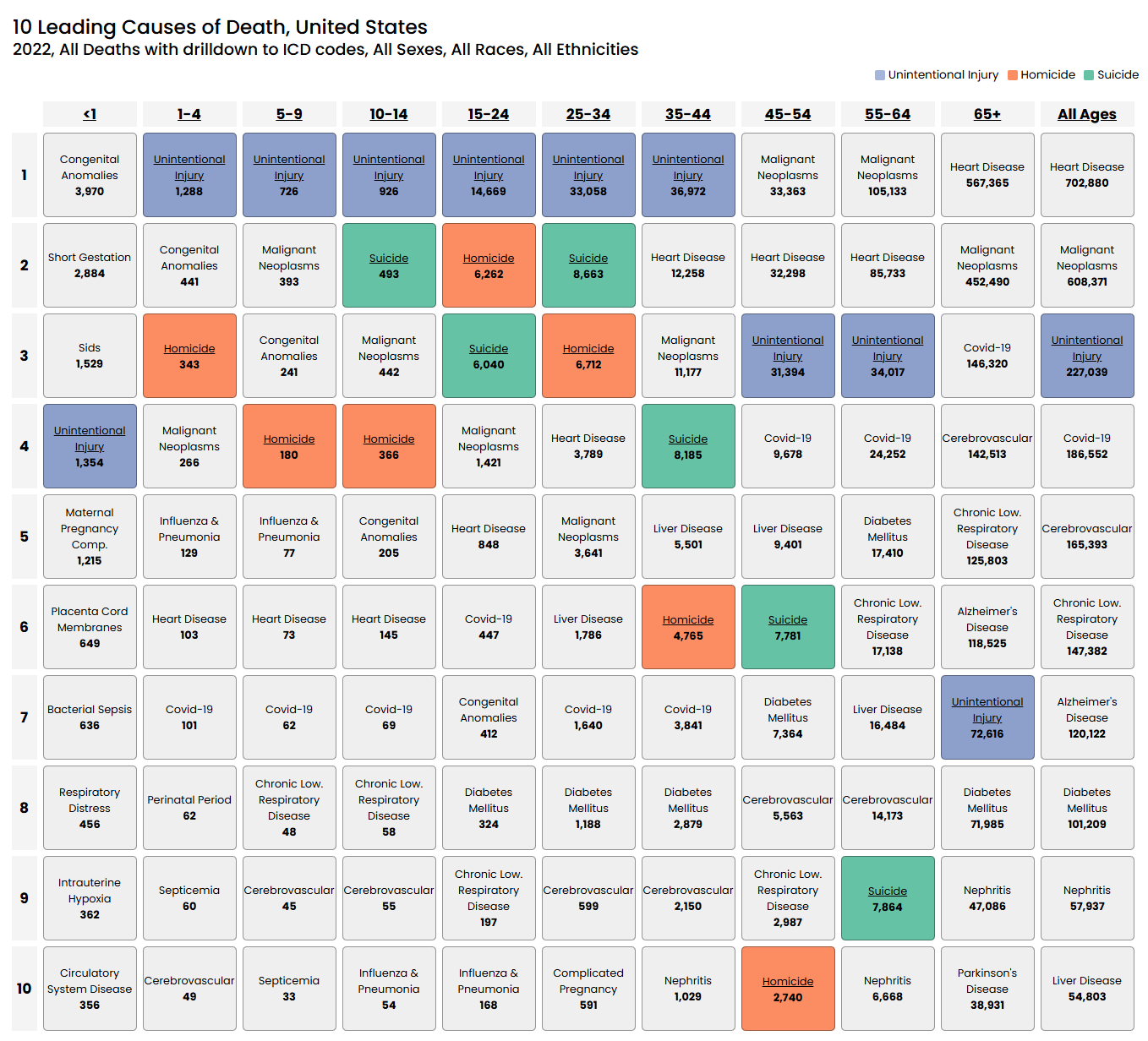

If we look through causes of death by age in 2022, then we see that cutting out even just the top-20 causes of death for those aged 65+ means losing 1,984,199 deaths out of 2022’s total of… 3,279,857. We’re losing just over 60% of the deaths and leaving ourselves with 1,295,658 to pull at least 730,000 from, and that’s not even counting out all of the deaths over age 65! But let’s be accurate and go all the way with removing deaths over age 65, bringing us down to 853,082 from which to pull 730,000.

Next we need to whittle down the remaining deaths, because many of them are clearly not plausibly driven by denials. For example, deaths due to unintentional injury and homicide are not being driven by denials because people cannot be denied emergency care thanks to EMTALA.1 In 2022, unintentional injury was the leading cause of death for ages 1-44, it was #4 for individuals <1 years of age, and it was #3 for ages 45-64. Then count out homicides, and it’s probably fair to just count out suicides too, since insurance denial is not really a documented correlate of suicide and the age groups with lots of suicides usually have fine coverage, but also for another reason I’ll get to in a moment. With all that out, we’re down to 625,979 deaths.

The next issue is that lots of young Americans are insured by another government insurance plan, Medicaid.

This cuts against the profit driven denial-induced mortality explanation offered by Senator Murphy.2 This also makes it harder to interpret the remaining deaths because they disproportionately affect those enrolled in Medicaid. For example, relative to those with private insurance, people with Medicaid are more suicidal.3 People on Medicaid also have much higher infant mortality rates than people with private insurance do, they have higher mortality in very diverse settings, and their mortality rates are, in general, higher. Medicaid also enrolls disproportionately many people with disabilities, and wherever you look, disability is associated with mortality. Medicaid is also disproportionately used by American Indians and Blacks, whose nonelderly mortality rates are much higher than the rates for Whites at the same ages.4

It’s unlikely that the greater mortality seen among Medicaid enrollees just reflects the quality of care they receive, because it is a program for low-income persons. It is necessarily selective about who gets enrolled, leading to confounded estimates of the cross-sectional mortality delta associated with Medicaid versus private insurance. But this isn’t relevant for our purposes, because we just want to know how much of the under-65 death we can be cross-sectionally attributed to private insurance plans, and for that, all we need to know is the mortality delta associated with Medicaid, confounded or otherwise.

Interpreting mortality under age 65 as being due to profit-driven denial of care was already hard to do, but with Medicaid and the high mortality of Medicaid enrollees noted, it should be very hard to do. To make this clearer, let’s look at the mortality for people under one year of age.

The top causes of death for <1-year-olds are largely things that happen around birth, like deaths from short gestation or intrauterine hypoxia, not really things that can be attributed to insurance denials, since care is already being provided at that point and it won’t be stopped and it’s obviously unlikely that a parent would call for it to be stopped regardless of cost. About 41% of all births in the U.S. happen to mothers with Medicaid coverage, and as noted above, their infant mortality rates are considerably higher than the rates for insured mothers.5 If we say that 41% * 1.15 = 47.2% of these deaths are Medicaid deaths and we keep the rest as private insurance deaths, then the plausibly profit-driven share of deaths declines by a few thousand, but if we were being maximally realistic, it should probably still go down even more.6

A lot of the deaths for people under one year of age are not preventable by the healthcare system. A denial shouldn’t matter for SIDS, sepsis, a neonatal hemorrhage, atelectasis, hydrops fetalis, delivery complications, and so on. Frankly, a lot of these need to be removed given the coverage mix (about half) and the feasibility of the system intervening for these conditions (the overwhelming majority of the remaining half!), but let’s be exceedingly generous to Senator Murphy’s position and just cut out half, and, at that, only half of the deaths from the top-20 causes of death, excluding what we’ve already parceled out. That reduces the death count from 625,979 to 618,999.

We then need to apply this logic to deaths from ages 1-64 too, because after all, how exactly is the healthcare system supposed to intervene on, say, diabetes, in a way it doesn’t already? And given the low socioeconomic status and thus high probability of Medicaid coverage for those who die below 65 years of age from causes like diabetes and heart disease, how can we chalk this up to the profit motive of insurers? I’m almost-certainly being extremely generous to Senator Murphy’s position by only counting out half of the deaths from the top-20 causes of death, and doing that brings us down to… 369,635 deaths.

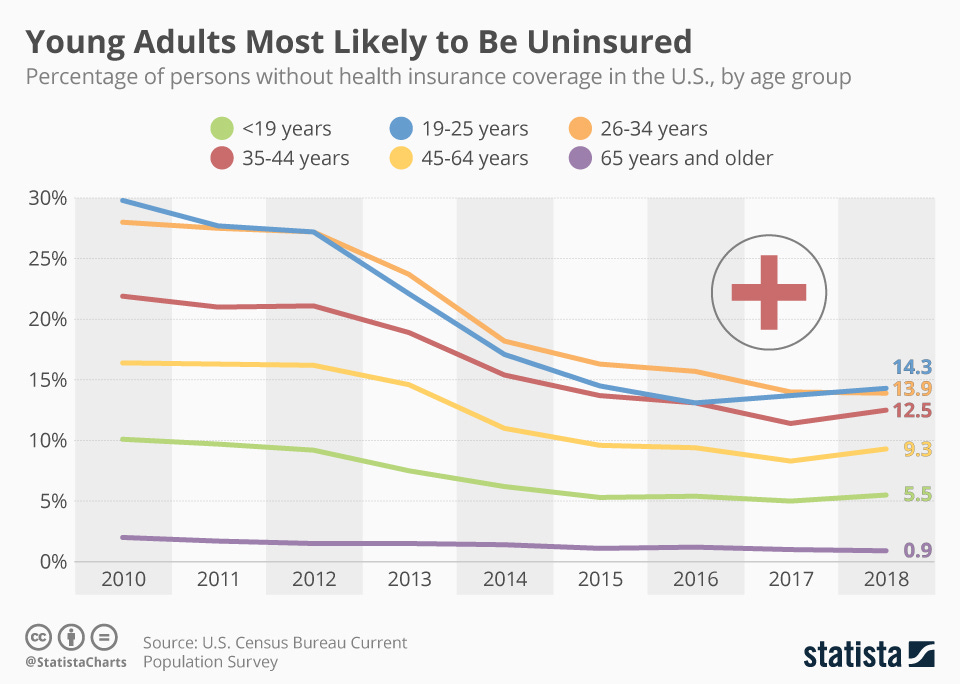

And we’re not done scaling this down. We still ought to scale this down to account for medical care received by the small portion of people who are uninsured, who are not suffering through care denials at the hands of insurers. The uninsured use care at lower rates than people with insurance, but their usage rates are far from zero. If we were to say, flatly and generously, that the uninsured use medical care at 25% of the rate of the insured ignoring that they would use critical care at more comparable rates, then we would cut deaths below age 19 by 5.8% * 0.25 and between 19 and 64 by 10.9% * 0.25, bringing us down to less than half what Senator Murphy proposed, and we’re not even done whittling down that number!

But I suggest we don’t go further than this. We haven’t exhausted the sources of public insurance coverage (cut another ~8%-12% from the initial number to cut from depending on how you treat Tricare), and we’ve been excessively generous with how treatable we’ve considered different causes of death, and it is already impossible to achieve Senator Murphy’s stated numbers. It is impossible to even support 1,000 profit-driven denial-based deaths per day! After all is said and done, even the estimate I’ve produced is still a major overestimate, but going further merely adds insult to injury.

So how might we figure out a good estimate?

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

Free Insurance, Limited Benefits

If we take Senator Murphy’s implied numbers seriously, then almost all non-homicide, accident, or suicide deaths for the young should be attributable to care denials and, accordingly, we should see an almost total elimination of mortality when nonelderly people obtain reliable access to medical care. The implied effect Senator Murphy stated would see doctor strikes having a near-genocidal impact7, it means Medicaid expansions should be majorly life-extending for the population, and when people gain access to care in other ways, practically any study should be able to show us huge benefits to mortality.

Let’s open up our handy-dandy copy of Joseph Newhouse and the Insurance Experiment Group’s Free for All?, turn it to page 211, and notice that in the RAND Health Insurance Experiment the book documents—in which people were given free health insurance—there was no effect whatsoever on overall mortality. There were two marginally-significant effects for “all elevated-risk persons” (p = 0.03) and for “elevated-risk and low-income persons” (p = 0.049), but if we believe these are real, they’re still far too small to justify Senator Murphy’s claims, and it’s not clear these findings would hold since the mortality benefits were apparently driven by blood pressure control and modern health plans cover blood pressure medication very well. In fact, private plans cover it as well as Medicare and Medicaid.

Newhouse also evaluated another free insurance experiment, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, in which people became able to receive Medicaid via a lottery. Whereas Senator Murphy predicts a huge effect on mortality immediately because denied care is critical to living, the reality of the experiment was that there was no effect on mortality (p = 0.638) at one year in. At two years, mortality didn’t even get a mention.

A deeper issue with this approach is suggested by the evidence that giving out free hospital insurance in the very poor setting of India didn’t impact mortality (p = 0.838) at 3.5 years post-intervention.8 If gaining access to hospital care doesn’t even materially affect mortality in a setting with extremely limited utilization of care—both before and after receiving free insurance!—, effects in America should be considered more doubtful. But not too much more doubtful, since the Indian study participants seem to have been affected by a lack of awareness of how insurance works.

If we look at a more optimistic estimate based on IRS notifications to get insured, we get a 0.06pp reduction in mortality among those aged 45-64 years of age who received a letter. This was marginally significant with a huge sample size, so it’s a result that’s more likely under the null. When I pointed this out to the author, he responded by restating the p-value as if that somehow made the result more believable. I am not sure why this would impress anyone, but I know saying a p-value twice does impress some people, so I can’t discount the strategy.9 A further problem with this is that this result is just for individuals aged 45-64 and we’re never presented with the results for individuals who are younger, but we are presented with estimated impacts on coverage, and we know those ages got covered less (but still a significant, positive amount) in response to IRS letters. We don’t know if it was statistically appropriate to split the sample by age because the authors provided insufficient documentation of their results, unless I missed something in a table somewhere. In any case, this stated result is in a higher-mortality age bracket than the bracket <65-years-old which we’re interested in for evaluating Senator Murphy’s claims. For the rest of that bracket, below 45-64, this study found “no evidence that the intervention reduced mortality… over our sample period.”

There are other studies that have looked at the impacts of expanded coverage too. For example, Currie and Gruber estimated that Medicaid eligibility expansion by 15.1pp between 1984 and 1992 reduced child mortality by 5.1%. Sommers et al. found that Medicaid expansions between 1997 and 2007 increased Medicaid coverage, decreased rates of being uninsured, decreased rates of delayed care, and led to significant reductions in all-cause mortality on the order of -6.1%. A later paper by Sommers et al. estimated10 that Massachusetts’ 2006 healthcare reform that pushed the state to near-universal healthcare reduced all-cause mortality by 2.9% and drove down deaths from causes amenable to healthcare intervention by 4.5%.

The ACA allowed Medicaid to be expanded substantially starting in 2014, and since then, there have been several evaluations of the mortality benefits to expanded coverage. Miller, Johnson and Wherry looked at ACA expansions across several states and focused in on the high-mortality population of people aged 55 to 64, finding a 7.0% reduction in year 0 and an 11.9% reduction by year 3 post-expansion. In aggregate, they documented an 8.1% reduction in morality relative to an estimated counterfactual mortality rate. The reductions in mortality for those aged 53-58 and aged 65 and older were nonsignificant. The reductions really set in only for those aged 59-64: old, but pre-Medicare.11 For a more general estimate of the mortality reduction from the ACA’s Medicaid expansions, see Borgschulte and Vogler, who estimated a decline of 3.6%.12

I don’t wish to make this section any longer, so I’ll say this: I’ve shown that insurance coverage matters, but the best evidence also strongly suggests that Senator Murphy cannot be right. The estimates based on providing free insurance, Medicaid expansions, IRS notifications, and other reforms suggest that increasing insurance has small-to-modest effects on mortality among at-risk populations, not that it has the gobsmackingly huge effects that Senator Murphy suggested it should among the whole population. And these are largely the effects of going from being uninsured to being insured, not from the more operative going from being insured with necessary care being denied to being insured with necessary care not being denied. Since going from being uninsured to being insured almost-certainly matters more than going from being poorly to less-poorly insured, and the effect of going from no insurance to some insurance (which mostly means public, not-for-profit insurance) is nowhere near enough. Being generous, Senator Murphy was probably off by more than an order of magnitude. There is simply no way to credibly argue for Senator Murphy’s claims.

Are You OK?

There is simply no way Senator Murphy could honestly support his conclusion that thousands die every day due to medical care being denied to support profits. Let’s review.

For one, there aren’t that many people denied care, and no one directly dies due to an insurer denial because you can’t even be denied healthcare for an emergency at the point of care.

For two, even if you take confounded cross-sectional estimates of the impact of being uninsured—which has a much larger impact on healthcare utilization than being poorly insured—on mortality, it’s insufficient to explain anywhere near a large enough portion of all deaths.

For three, too few deaths happen among those with private insurance alone for his claims to be true.

For four, there aren’t enough deaths from medically preventable causes at the right ages for his claims to be true.

For N, we can go on! There are so many lines of evidence that Senator Murphy should have known that would have disconfirmed his claim, and yet there he was, making it before an audience of millions.

Politicians are infamously dishonest. A lot of that probably has to do with just being ignorant. Politicians usually aren’t exceptionally brilliant people, and there’s no end to the reporting on their dumb gaffes and mistakes. Given his statements, it’s clear that Senator Murphy is no exception, and he would have benefited from checking his numbers and having someone there to give him a sanity check before he opened his mouth. More generally, every politician should have this when it’s time to make empirical claims.

But being wrong about healthcare isn’t Senator Murphy’s worst sin. There’s a far more fundamental and pressing issue with Senator Murphy’s claims than just being wrong. His video’s entire purpose was to turn a senseless murder into a call for action against people whose harms he was actively exaggerating. His goal with the video was to vindicate violence by way of people feeling aggrieved over a problem that neither the killer nor he seem to understand.

Imagine if a sitting Senator who started their Congressional tenure in 2024 was killed in cold blood over an issue like U.S. military bases in Iraq. One could argue that people are disheartened and fed up with American military deployments and the Congressmen who contributed to them. By Senator Murphy’s standards, such a murder would be justified. To quote him: “People in America today feel ignored, they feel scared, they feel alone in a system that intentionally grinds them down. A system where profit matters more than life. My colleagues need to listen and we need to do something about it.”

My suggestion for Senator Murphy’s “something” is to be a little more sane, to get a lot more informed, and to be much less sensitive to the half-baked arguments of psychopaths who kill Americans in cold blood. Maybe then he can start to fix the healthcare system.

Notably, this applies to Medicare-participating hospitals and you cannot reasonably blame the healthcare system for the very small number of cases where people do not pursue critical care because they believe they won’t be able to pay for it. That’s not the fault of a system that won’t deny them the care they need.

It’s also important to understand that recent increases in coverage since the passage of the ACA have been largely driven by increases in Medicaid coverage, often at the expense of better, private coverage.

This study also found a potentially composition-driven effect of the ACA on Medicare-related suicide risks.

The mortality rates for the completely uninsured are also relatively high, but they constitute a very small portion of total births.

You could argue that some number of deaths are due to Medicaid enrollees’ coverage lapsing before or after pregnancy, but the impact of this would be small even if you maximized the possible number.

They actually tend to have null or positive impacts, suggesting healthcare is overused.

As noted in this study, the quasi-experimental literature (which they mistakenly called “quasi-empirical” in Footnote 1) produces split results on mortality benefits.

For whatever it’s worth, the author of that paper did bring up another recent study, suggesting that cost sharing reduces drug usage, resulting in mixed and generally marginally significant effects on mortality. This isn’t relevant here, but it is relevant to the idea that drugs matter for survival in general.

With a method that’s liable to leave a lot of residual confounding and with results that do not seem very robust. See the commentary on the article.

Although I’d caution that, though this makes theoretical sense to see risk rising with age, splitting the sample reduces power, and this is already a domain where power is very concerning.

There is also, to my knowledge, just one sibling controlled estimate of the impact of Medicaid eligibility expansion, but it’s about childhood expansion impacts on adult outcomes, and it was dubious. The inclusion of the sibling control or family fixed effects turned results for impacts on cumulative total taxes at best marginally significant, but didn’t meaningfully affect their magnitude. It’s unclear how to interpret this given the statistical uncertainty.

The smartest take down on the dumbest senator.

Thanks for a more balanced overview of the American health care system than that generally found by substack authors. Several substack authors target an audience of naysayers who badmouth every aspect of our healthcare system. Some prolific authors publish 2-3 or more articles daily, hashing the same screed repeatedly. They are after monetary gain rather than public safety.