Go Ahead And Have Kids

Depopulation won't stop climate change, but your kids might

Fear of climate change is commonplace among today’s youth. Large numbers of young adults report feeling hesitant to have children for reasons having to do with fear of bringing children into a warmer world or because they want to avoid contributing to climate change. These concerns are not just American or Western ones, they’re felt by people the world over. But are they valid?1 A new preprint may have an answer.

The preprint uses economics’ workhorse model for analyzing the impacts of climate change, the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy—DICE—model. The DICE model was invented by William Nordhaus in 1992, and its climate-related predictions for 2015 held up well. DICE population predictions were close to the mark and the model’s predictions about economic variables like per capita GDP and consumption per capita were also not that far off, although the model was consistently pessimistic about them. For 23-year predictions, the performance is pretty impressive.2

The new preprint expanded the DICE model to be more realistic in three ways:

(i) Technological progress increases in population size based on the endogenous growth literature;

(ii) the distinction between total population and labor is explicitly represented, such that an economy with more children or retirees has lower GDP per capita, other things equal; and

(iii) emissions from deforestation and other sources of land use scale with population.

With this model in hand, the authors sought to compare two scenarios:

Depopulation: The U.N.’s “Medium” 2022 population projection for the globe, within which populations transition to lower fertility and decline; versus

Stabilization: The same projection, except global populations immediately and indefinitely have their fertility rates bounded from below at the replacement rate.

The global population in those scenarios looks like this:

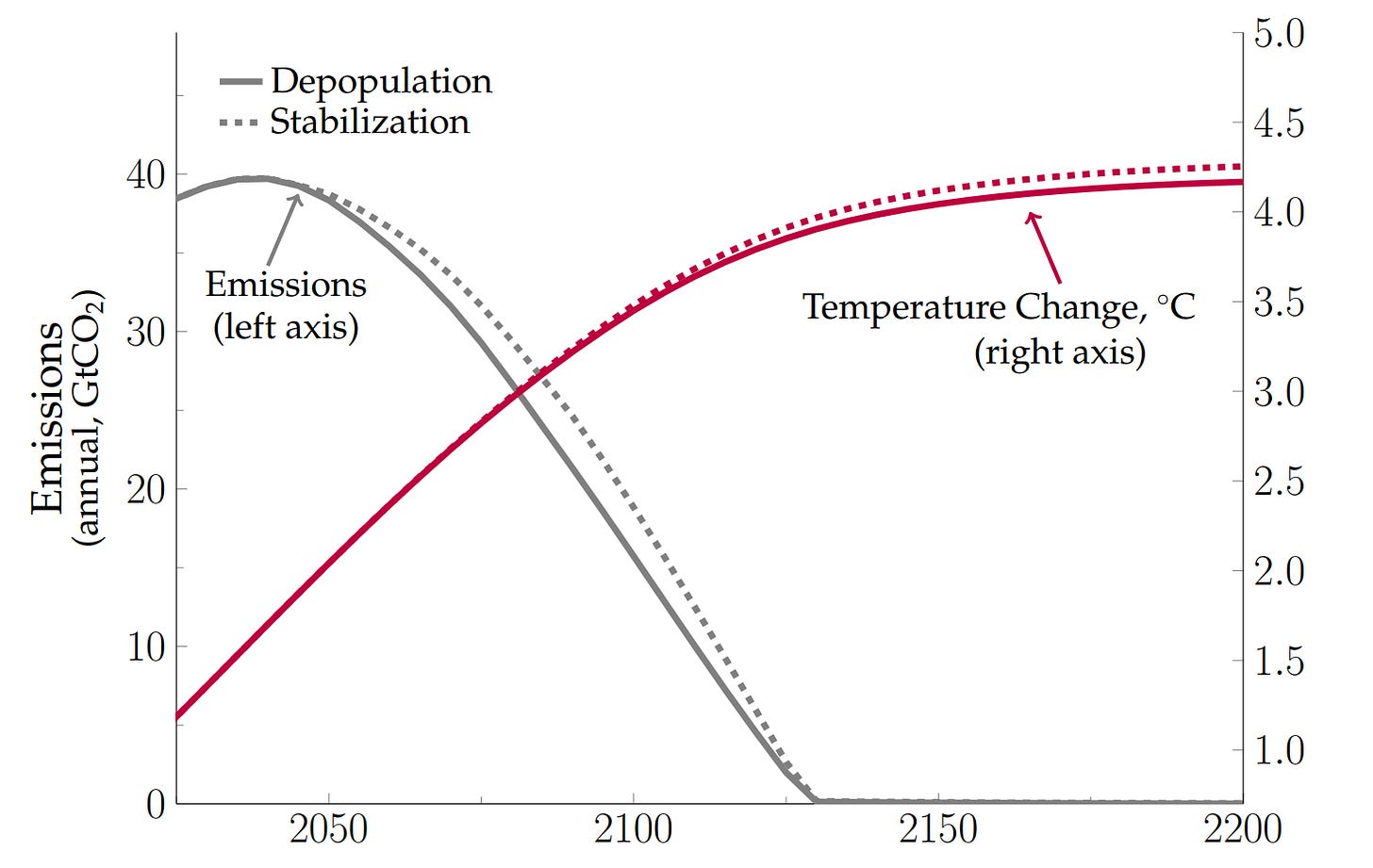

Though these scenarios result in massively divergent population numbers over the next two centuries, the fact that emissions are expected to decline shortly despite increasing productivity means that the fertility shifts that will slowly shrink total population size result in minimally different emissions and temperatures in the long run. Or in other words, long-run warming barely differs between Stabilization and Depopulation even though Stabilization results in a 90% larger population by 2200.

Having more kids is unlikely to doom the world through climate change, so we can check off one worry.. The next one is that the kids will live in a worse world. That too can be discounted, because more people will tend to mean greater productivity and accordingly higher quality of life, if history is any indication.3

Relative to Depopulation, there’s an initial, short-term dip in real GDP per capita for Stabilization because of the greater emissions levels. This dip is not an absolute decline in living standards, just a relative one. This relative dip is quickly overcome by the greater levels of innovation and resulting improvements to productivity that follow from having a larger population. This result holds across 192 different specifications whose parameters range between reasonably optimistic and extremely pessimistic:

In realistic models of different population trajectories for the next two centuries, the conclusion is clear: holding off fertility realization due to climate pessimism is unwarranted. In fact, it’s likely to be a net harmful decision for the world. If more people have more kids, that’s likely to make the world an even better place to live in, even though there’s climate change to contend with.

But let’s be even more realistic about this. In the real world, countries are already decoupling emissions and economic growth and there are available methods to stall global warming indefinitely at low cost. The implications of that latter fact are momentous. To quote Bundesbank economist Tom Holden:

Technological progress ensures that extracting CO2 will be cheaper in [the] future, in part due to declining energy costs. In the presence of [this sort of] technological progress, a problem delayed [is] essentially a problem solved. All problems are eventually trivial.

So please, stop worrying. Don’t forego family life because you’re concerned about the climate. Rationally, you should reverse the worry, if anything: you should be concerned about not having kids if you really care about humanity. And, if you’re the sort of person who has enough wherewithal to panic about climate change, you’re probably the sort of person likely to have kids who will make the planet healthier.

I am aware of the complaint that human capital will decline in the future as births shift from East Asia to Africa. This is addressed in the stabilization scenario by the fact that all countries’ fertility is bounded, so the distribution of births by regional human capital levels can at best shift marginally, and may even improve in the near-term. If this were modeled, we would see that the Stabilization scenario would almost-certainly end up even better off than the Depopulation one due to the reduced shift towards regions with lower levels of human capital.