"Harvard Study Says..."

Why a recent systematic review of the link between autism and acetaminophen only tells us that its authors were too incompetent to write it

The most prominent defense of the HHS’ decision to warn mothers about the autism-promoting risk of acetaminophen (paracetamol, Tylenol) is that a great new study came out that established the risk was real. I’ve already gone over why this conclusion is unwarranted; briefly, the study ignores good evidence in favor of poor evidence.

Now, I’ll more comprehensively go over the evidence that review cited, the cheap excuses the authors relied on to make their conclusions, their documented lies and conflicts of interest, and then I’ll finish this off with a review of the available causal evidence related to the review including some new evidence.

What the Review Says

To start, the review is a complete mess. It’s written by an environmental epidemiologist (lead author Andrea Baccarelli), another environmental epidemiologist (Beate Ritz), a children’s environmental health researcher (Ann Z. Bauer) who wrote a fake consensus statement (a consensus of who? of what evidence?), and a researcher at the Institute for Health Equity Researcher at Mount Sinai (Diddier Prada). None of these people have experience with pharmacoepidemiology and it shows in their choice of systematic review method: “Navigation Guide.”

This methodology is curiously entirely unused in pharmacoepidemiology before now. Perhaps that’s for the better, as it appears to have allowed these researchers to conduct an inconsistent analysis that portrays decidedly noncausal findings as if they’re causal. This fact was noted in court when Dr. Baccarelli appeared as an expert witness and the court repeatedly noted that he was inconsistent in his application of methods including the Navigation Guide methodology, that he was repeatedly contradicted by the sources he cited, that he cited evidence that had no relevance to the case, and that he conflated evidence for different types of conditions—among many other issues—before eventually stating to the court that “there is strong evidence of a causal link between prenatal acetaminophen use and an increased risk of being diagnosed with ASD in children.”

Dr. Baccarelli’s testimony—which now more popularly takes the form of the review everyone is citing—was eventually dismissed, but not before the court humiliated him. The remarks from the court are stunning. I’ll quote a particularly revealing segment where the judge thrashed him for his habit of selective citation:

Perhaps most tellingly, Dr. Baccarelli separated Gustavson 2021 into two studies: the initial data (which reported an association, and which Dr. Baccarelli rated as “strong evidence”) and the sibling-control analysis (which attenuated the association, and which Dr. Baccarelli downgraded from “moderate” to “weak” evidence “due to concerns about small size and the bias towards the null likely introduced by the elimination of the effects of intermediate factors”). Yet he did not similarly downgrade Brandlistuen 2013, discussed supra, instead rating it as “strong evidence” that acetaminophen causes other [neurodevelopmental disorders, or NDDs]. But Brandlistuen 2013’s sibling-control analysis would similarly “eliminat[e] the effects of intermediate factors,” and it included 134 sibling pairs discordant on exposure for greater than 28 days. Id. at 1704. Gustavson 2021, having the benefit of several more years of data on the same cohort, included 380 families with siblings discordant on exposure for 29 days or more. Id. at 5. This is a paradigmatic example of interpreting results differently based on the outcome of the study, Zoloft II, 858 F.3d at 797, and it is illustrative of Dr. Baccarelli’s approach to the Navigation Guide, in which he uses areas where an expert’s subjective opinion comes into play to selectively downgrade studies not supporting his analysis and vice versa. [emphasis mine]1

Later on:

Dr. Baccarelli failed to sufficiently explain the appropriateness of conducting a single Bradford Hill analysis for NDDs which included ASD and ADHD, selectively analyzed the consistency of the literature and the issue of genetic confounding, repeatedly pressed conclusions that study authors were not willing to make, and disregarded studies that do not support his opinion due to limitations that he did not view as disqualifying in studies that did support his opinion. Together, these deficiencies demonstrate that his opinion does not “reflect[] a reliable application of the principles and methods to the facts of the case.” Fed. R. Evid. 702. Thus, Dr. Baccarelli’s causation opinions are not admissible.

This is the sort of thing that you’re in for if you read this review. So, let’s read it!

Firstly, the method used in this review is supposed—per Dr. Baccarelli—to be used transdiagnostically, but for some reason, three separate reviews were done: one for ADHD, one for ASD, and one for other NDDs. Why? It’s not clear. At times, the review conflates findings across diagnoses, and at other times it separates them, seemingly always in a way that exaggerates the harms of acetaminophen. Curious.

We’ll start in Table 1, the list of studies cited on ADHD.

Right off the bat, we are greeted to a list that makes the review seem inconsistent. Before this point in the review, the authors wrote:

While a meta-analysis could provide quantitative synthesis, we opted against it due to significant heterogeneity in exposure assessment, outcome measures, and confounder adjustments across the studies evaluated. This variability, combined with non-comparable effect estimates, risked biased pooled results.

Yet, they apparently took no issue with citing a meta-analysis—Alemany et al. (2021), which they cited as Alemany, 2021—and not even noting in the table that it was a meta-analysis.2 In fact, they never noted that this was a meta-analysis, not in the table, nor when they directly discussed the study. This isn’t damning, but it’s the sort of thing that should at least be declared for consistency. The damning thing is how they treated this study in light of their remarks.

While they note that meta-analyses are difficult due to all the inconsistencies in reporting of outcomes and exposures, they did not note that this meta-analysis was not excepted. Instead, they declared that it had a very low Risk of Bias for both ADHD and ASD. This is despite the fact that the study conflates extremely heterogeneous measures across six cohorts and only achieves an overall significant result due to one of the studies. Moreover, that result refers to effects on symptoms within the borderline/clinical range, assessed using parent- and teacher-reported questionnaires.3 Including diagnoses, the study’s reported effect on ASD becomes nonsignificant and the ADHD association becomes somewhat larger, but as a result, the outcome becomes all the more heterogeneous and uninterpretable.

For some reason, the review is missing the ratings of bias for the ADHD-related studies even though it has it for the ASD and other NDD studies. We don’t get to see how good or bad Alemany et al.’s measured are rated, but we get a hint from the study grading: despite its small effect size, Alemany et al. is cited as showing moderate evidence for a large effect. Despite explicitly saying “we did not address dose-response relationship [sic]”, the review says that Alemany et al. provided moderate evidence for a dose-response effect! In the study grading for ASD, the study is once-again cited as showing evidence for a dose-response effect and somehow it has a higher “internal consistency” rating than in the ADHD grading section, despite the study showing lower internal consistency and less robustness for ASD than for ADHD!

This is just one study, and I can go on about it because there’s even more that’s just not treated correctly about it, but pretty much every study was treated this poorly and inconsistently with the statements they made throughout their review, so focusing on this one (improperly cited and graded) study any longer feels like a waste of time to me.

The meconium (baby’s first poop)-based study by Baker et al. is the strongest evidence in the whole review for a dose-response relationship, and it isn’t impressive. This study has nothing to do with autism and is entirely focused on ADHD, so it’s not really relevant to yesterday’s announcement. Nevertheless, it should be discussed to get an idea about the review authors. In Baker et al.’s crude specification, the dose-response result is marginally significant (p = 0.02), and in their adjusted specification, it remains marginally significant (p = 0.01). Despite this being crucial to cite to support a dose-response relationship, the authors referred instead to the binary result for no acetaminophen versus acetaminophen detected, which was marginally significant (p = 0.03) before adjustment and became highly significant but still had a wide confidence interval after adjustment.

The study grading also said there was greater control of bias than in Alemany et al.’s study, but adjustments were more minimal, so it’s hard to see on what grounds they made this judgment. Perhaps it was on the basis of exclusively using diagnoses? I really don’t know, but it’s hard to see.

The other study that was crucial for the review to cite to support a dose-response relationship is Ji et al.’s study of cord plasma acetaminophen biomarkers. This study is so absurd that it was dismissed outright in court. In fact, the most authoritative debunking of this study comes from the European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS), which also castigated one of the review coauthors—Ann Z. Bauer— for her fake consensus statement on acetaminophen in pregnancy. In that criticism, they note that Ji et al. is a study whose results cannot be trusted:

This study has severe issues with external and internal validity. APAP [(this is another name for acetaminophen because its alternative name is N-acetyl-para-aminophenol)] or metabolites were detected in every single of the 996 umbilical cord samples. This does not compare well to our knowledge on the use of APAP during pregnancy. Among the 996 children, an unprecedented large proportion were diagnosed with ADHD/ASD (37%) and only 33% had no “developmental disability” diagnosis. Population prevalence estimates of ADHD is around 3-5%. The validity of the exposure construct “burden of APAP exposure” is undocumented and actual levels are not presented. Analytical methods are insufficiently accounted for including stability from up to 20 years of sample storage.

If ENTIS knew how this study would be cited by this more recent review, perhaps they would’ve been even more severe. Interested readers will note that Ji et al. is not cited in the studies on other NDDs. Curious! Why? It should’ve been! The single largest sample of kids analyzed by Ji et al. (n = 304) was for other NDDs! This is larger than the combined ADHD and ASD sample (n = 42), the ASD-only sample (n = 66), and the ADHD-only sample (n = 257). I know exactly why they excluded this result from the broader NDDs analysis: it found a negative result! There was not only no dose-response relationship for other NDDs, the effect went nonsignificantly in the ‘wrong’ direction, so no wonder it wasn’t cited.

To make the review’s evaluation of this study even worse, they claimed it had the lowest risk of bias among all the studies they provided Risk of Bias ratings for. In reality, it probably had the highest because of its incredibly unrepresentative sampling, obviously errant portrayals of acetaminophen usage rates in pregnancy, and the fact that it used a biomarker that only indexes perinatal exposure—exposure happening within the last three days rather than over the course of pregnancy.

The Ji et al. study cannot be relevant or informative, and both Dr. Baccarelli and Dr. Bauer were aware of this due to the fact that they both cited this study and got reprimanded for doing so, in court and by a major European medical association, respectively. They knew better, but they cited it anyway; to make things worse, they cited it incorrectly. This is beyond the pale, but it’s not even the worst offense in this abomination of a review.

Consider the 2016 study by Avella-Garcia et al. This study is cited for ASD and ADHD and per the Risk of Bias assessment, it has excellent outcome measurement and is the second lowest-risk study in the review. In the table of ADHD studies, the effect estimate is cited as an IRR of 1.25 (nonsignificant) for ADHD, but this effect was not for ADHD, it was for a symptom score. Further, they cited an IRR of 1.41 for attention/impulsivity symptoms. But when you go to the study, you discover that this is an inaccurate description. In fact, this IRR is the adjusted, p-hacked IRR (p = 0.045) for “Hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms”. The adjusted IRR for inattention symptoms is 1.12, and is very nonsignificant. For some reason, the review authors didn’t cite this part!

The authors’ table did not mention the study’s results for scores on the K-CPT, perhaps because those results were nonsignificant for the combined score or because they were inconsistent by sex. The grading table did mention that Avella-Garcia et al. provided very strong evidence of internal consistency—despite their incredibly inconsistent results—and very strong evidence of a dose-response effect—despite the fact that the authors could not evaluate dosages—in addition to moderate evidence for a large effect—despite all effect estimates entirely excluding a large effect.

The dose-response analysis that is present in the study is strange, and clearly not “very strong” evidence in favor of a dose response effect. The analysis is based on comparing mothers reporting acetaminophen usage never vs in 1-2 trimesters vs in all 3 trimesters. For the K-CPT’s omission errors, maybe there’s evidence of an effect comparing users across 3 trimesters versus lesser users, but it’s nothing to write home about. The p-value on this is extremely marginal at just 0.036. The other results that can plausibly be commensurate with anything else in the review are all nonsignificant, and if anything, show evidence against a dose-response. For example, for the K-CPT’s detectability scale, there’s a significant negative result for 1-2 trimesters of use, and a nonsignificant result for 3 trimesters of use, although these are not significantly different (a fact that doesn’t seem to matter to the review authors).

The only thing consistent in this review is the studies are cited and graded incorrectly. Another of the studies tossed out in court made it to the review and illustrates yet again how incompetently conducted the review was. This study was Liew et al., and it used the one dataset used by Alemany et al. that made their results consistent. It’s quite remarkable that this study was miscited because one of the co-authors was Beate Ritz—a review coauthor!

The study has a marginally-significant (p = 0.01) overall +19% risk elevation comparing ever using acetaminophen during pregnancy to never using it. This only holds for autism spectrum disorders, but the authors fail to achieve a significant result for infantile autism. These results are not significantly different, so they should likely not have been broken up. Pooling them in an inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of the log(odds ratios), the effect is a 17% risk elevation with a p-value of 0.01. Basically the same, so no big deal, right? Possibly, but likely not. The real finding is that there is a significant interaction such that there was no apparent effect of ever using acetaminophen in the larger sample of kids without ADHD, and there was an effect only among those who had ADHD. Moreover, there was no dose-response among those without ADHD, and there was only a marginally-significant dose-response among those with it. This result is for ASD, but if we combine these results with the ones for infantile autism, then the p-value for trend rises to 0.24.

This is not much of a result. It seems fine to cite, but the authors never mentioned this interaction with ADHD, nor did they mention that this is the opposite of the Ji et al. result. More crucially, the authors cited this study as showing strong evidence for a large effect, but none of their coefficients was high enough to pass their threshold except for the nonsignificant one for infantile autism for individuals with ADHD who were exposed to more than 20 weeks of acetaminophen usage—an effect eliminated by combining the infantile and ASD results anyway. So this was a lie. They also said that this provided very strong support for a dose-response. There was no dose-response, properly-considered, and the evidence they looked at was marginally significant anyway. The results were also not internally consistent—the results with and without ADHD differed dramatically!

Amazingly, the authors cited this study in the tables on ADHD and NDD studies despite the fact that the study did not analyze ADHD or NDDs separately. In the ADHD table, they cite three statistically nonsignificant odds ratios (p = 0.05 is nonsignificant) for subnormal overall attention, selective attention difficulties, and parent-rated subnormal executive function. In the table for NDD studies, they say that it showed a mean 3.1-point IQ reduction for people who were exposed for 1-5 weeks. What about overall? What about for more weeks? We don’t know. The result is unavailable to us because it isn’t in the cited study. This isn’t because of one of their several typographical errors either—they actually cited Liew et al.’s 2016 study and stated that it produced different results from Liew et al.’s 2014 or 2019 studies, even though it did not report the outcomes they say it did! Incidentally, even though Liew et al.’s 2016 study is listed in the NDD study table, they don’t cite the only actual NDD result from the paper: the null supplementary result for Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. They also differentiate this study’s grading for NDDs and ADHD from the erroneous one we already know of for ASD, we just can’t evaluate that, except to say that their claims don’t hold for at least PDD-NOS. Oh well!

At this point, I’ve gone over all of the ASD studies except for the best one: Ahlqvist et al. The evaluation of this study was a doozy because it was all just so incredibly fake.

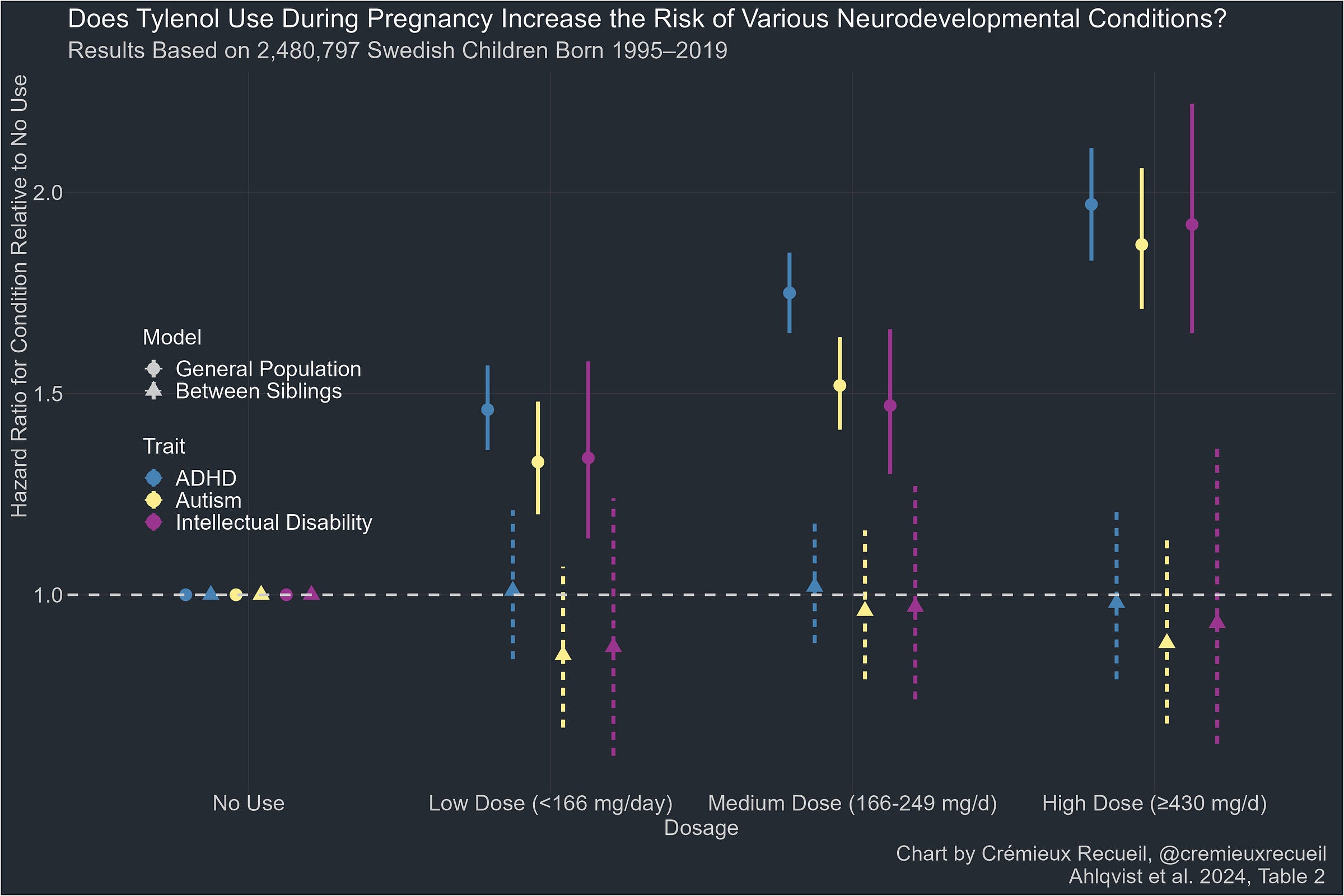

In reality, the Ahlqvist et al. study is by far the best study cited in this entire review. It used ICD codes for diagnosis determination rather than relying on poor quality parental or teacher questionnaires; it used structured interviews by midwives and physicians 8-10 weeks into pregnancy and then again later and it replicated this analysis with prescription numbers in a country where most acetaminophen usage is by prescription. This study had the least bias by recall, it had by far the largest sample (millions of individuals and over 16,000 sibling pairs), and it didn’t rely on biomarker-based acetaminophen assessments that are too unreliable to take seriously.

And yet, the authors misdescribed it and dismissed it. The reason is presumably that its result is so clear: there was no causal effect of acetaminophen exposure when comparing siblings exposed to it versus siblings not exposed to it.

Looking only at the non-causal, cross-sectional analysis, for some reason, for ASD, the authors suggested that this study provided weak evidence of a large effect, when they said Ji et al. provided strong evidence. Why is this inconsistent? Because Ji et al. only shows a large effect with extremes stratification, just like this study. The point-estimate doesn’t cross 2 here, but the CIs do, and they do so with considerable precision, so this is good evidence of a large effect cross-sectionally if we’re going to treat studies comparably! But the review does not treat studies comparable, or even sensibly at all. Consider their statement about the sibling-controlled analysis: apparently that shows moderate evidence of a dose-response effect! Do you see evidence of any dose-response effect? I can’t!

They said the same for ADHD, but for some reason omitted this study for NDDs despite the intellectual disability findings. The inclusion criteria and treatment of these results is just so incredibly inconsistent and untethered from reality. That’s really all there is to this: it cannot be taken seriously because nothing matches up as it should if the authors were being serious in their review.

To make matters worse, the authors selectively applied various arguments against Ahlqvist et al. and other studies they disliked. The court case Baccarelli was humiliated in noted this, but I should too.

The authors downgraded Ahlqvist et al.’s exposed rating and said it had limits. But it was superior to the exposure outcome for practically every other study! They stated that exposure assessment relied on midwives in order to make it seem like the study had weak exposure assessment, but the results were replicated using prescription information, and the midwife surveys were superior to the surveys used in practically every other study. What is this criticism if not an indictment of everything the authors liked? It’s obviously just inconsistent for the sake of saving their preferred findings from falsification.

The authors attacked the Ahlqvist et al. study for allegedly getting the usage rate of acetaminophen wrong, but they didn’t even read that this is actually quite consistent with what we know about acetaminophen usage in pregnancy even though Ahlqvist et al. explained this and provided citations to this effect! Unsurprisingly, we know the authors should’ve known this because they read Ahlqvist et al. and ENTIS stated similarly to one of the review’s coauthors.

Even worse, the authors’ criticism of Ahlqvist et al. proved they do not understand how different biases should act on estimates (e.g., by stating that a bias that would move sibling-controlled studies to the cross-sectional estimate should move them to the null); they provided evidence that they did not actually read or comprehend the specifications in Ahlqvist et al. (e.g., by stating that they overcontrolled for relevant conditions when they in fact did not control for these balanced conditions); they failed to recognize that their only legitimate bias complaints applied as well to the cross-sectional as to the within-family results; and they read Ahlqvist et al. to look for some sort of bias they could suggest was present—”carryover bias”—and mentioned that offhandedly so they could dismiss the result.

The authors of the review seemingly discovered carryover bias by reading Ahlqvist et al., who took the possibility seriously and testing for it. The review failed to mention that Ahlqvist et al. evaluated the possibility of carryover bias and found that it didn’t explain their results. They note that Ahlqvist et al. couldn’t reject the possibility of carryover bias for the ADHD outcome, and alright! But the bias was balanced with an OR of 0.83 for if the first child was the exposed one compared to 1.12 for if the second child was the exposed one, thus making the net effect on the aggregate results effectively indistinguishable from nothing. Moreover, the review failed to mention that Ahlqvist et al. even assessed the potential impacts of “if acetaminophen use had been substantially underascertained” in their sample and in that case, that still wouldn’t explain their results. The review just ignored all this in favor of their preferred result.

This last part brings me to a wonderful point: the reviewers don’t understand how recall error can bias study results. They repeatedly suggested in the review (and Dr. Baccarelli did this in court) that estimates were biased towards the null, when they could very well have been biased upwards, as in the case for the link between ovarian cancer and talc. It could also very well be the case that misremembering could be systematic; correcting it could also expand standard errors and render published estimates nonsignificant.

All of this depends on the sensitivity and specificity of recall, and for medicines typically used in the short term, sensitivity is often very bad. For example, acetaminophen recall in this 6-week diary study had a sensitivity of 0.57. Comparing first trimester interviews to prospective diaries, this study arrived at a sensitivity of 0.786 and a specificity of 0.623 for NSAIDs. Comparing self-reports to urinary metabolites, it’s clear that there’s high agreement with recent reports, but there’s also underreporting afoot. There’s some evidence that, at least the recall of OTC medications shouldn’t be biased when comparing people with typical and disabled children.

If we adapt the code from the talc case to, say, reassessing Liew et al.’s 2019 ADHD paper, and use the NSAID recall figures I just cited, then, well, the apparent bias is too extreme and none of the simulated draws are valid. So, being very generous and setting the specificity to 97% and the sensitivity to 85% and applying this to the main analysis at time of pregnancy sample in the study, the estimated odds ratio increases from 1.34 to 1.45, but it goes from having a confidence interval from 1.09 to 1.64 to below 1 and above 4—or in other words, nonsignificant.

I could go on. The review is very bad, but now that I’ve covered the ASD studies, I think I’m sufficiently done with it for people to understand the situation we’re in.

What the FDA Cites

The FDA cites… Ji et al.—which we saw was a horrible study—and Liew et al.’s 2019 study—for which we saw a not-so-robust result on reassessment, and for which we can see not-so-robust results by just looking at the paper. The main analysis result for the time of pregnancy ended up with a piddly p-value of 0.02. Restricting the analysis to mothers who are pregnant at the time of assessment so as to reduce recall bias, that rises to 0.041. What a great coincidence that it remains just-significant!

In the supplementary analysis with full adjustment, all the results were nonsignificant. The authors also claimed that by using data on pre-pregnancy and post-pregnancy acetaminophen usage reports and finding that the results of using said data were generally null whereas the main result for pregnancy usage was not, that they had controlled away genetic confounders. This is an absurd conclusion for a few reasons, not least of which is that the negative control results were not significantly different from the pregnancy results and thus it is improper to separate them.

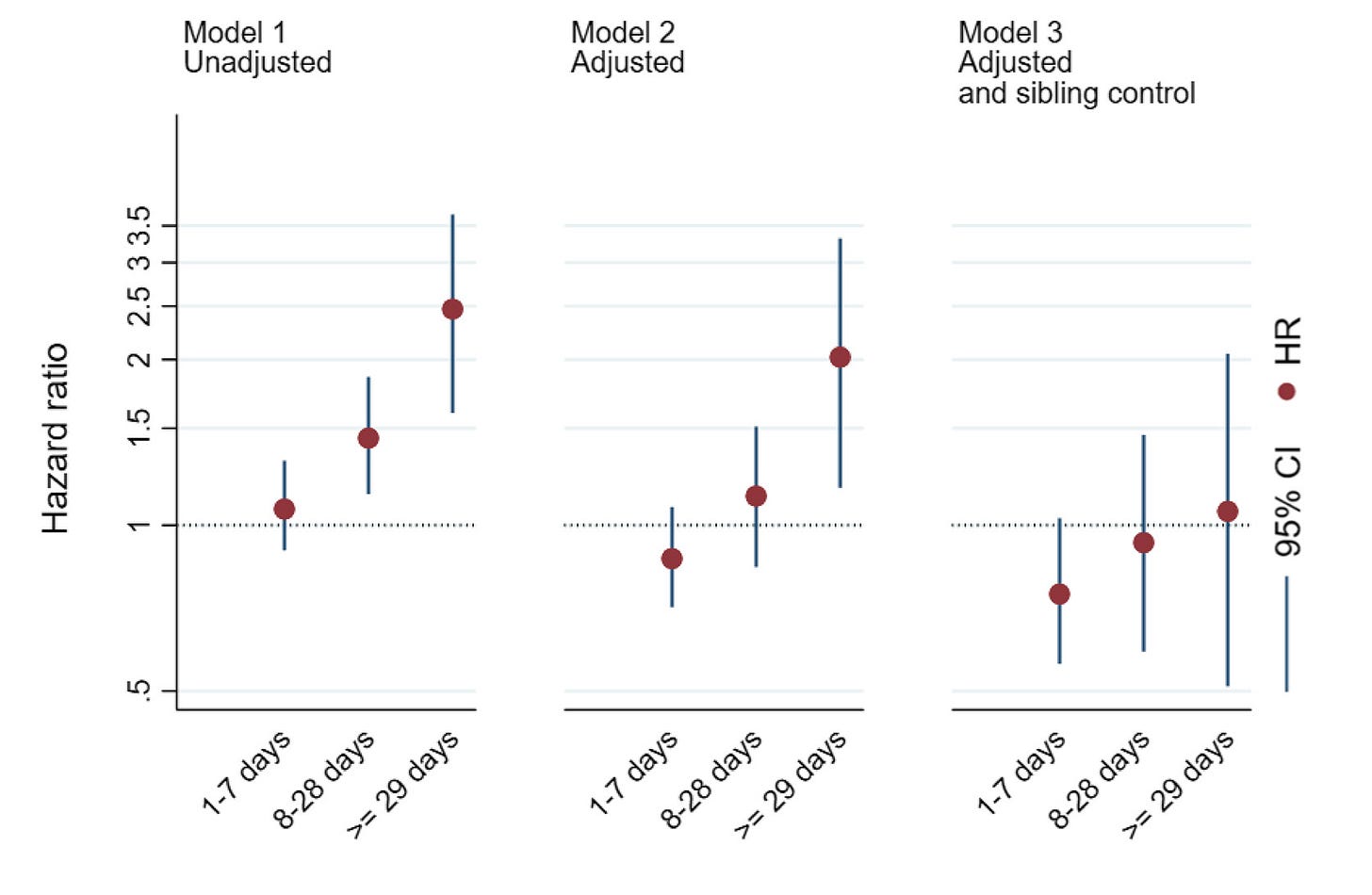

The FDA did not cite the massive Ahlqvist et al. sibling-control study we have for autism and ADHD instead of the shoddy Ji et al. study and it did not cite the large Gustavson et al. sibling-control study we have for ADHD instead of the shoddy Liew et al. study either. The Gustavson et al. result—which the court called out Dr. Baccarelli for ignoring in favor of an earlier, more favorable result from the same cohort when it had less data—is very clear. There’s no risk elevation for ADHD:

What the Public Apparently Sees As Evidence

The same blanket warning every careful company provides is the sort of thing that the public sees as evidence that Tylenol is harmful for pregnant women and their developing children. This says nothing about whether there’s harm from using Tylenol during pregnancy and it certainly says nothing about whether the company might secretly know harms are afoot. But that is how delusional people, who evidently have no real understanding of the healthcare system, interpret it.

The public has such bad epistemics that this section could be limitless, so I’ll end here.

Causal Evidence

The aforementioned sibling studies by Gustavson et al. and Ahlqvist et al. are the strongest pieces of literature published on this topic and they show us extremely strong evidence that there is no causal role for acetaminophen in autism or ADHD. Beyond that, there’s little published evidence. If I had to guess why, I’d suggest it’s because pieces like Gustavson et al.’s and Ahlqvist et al.’s are reactive; they’re responses to people getting carried away with bad theories about acetaminophen causing all sorts of problems that it doesn’t. In the world we live in, we know acetaminophen is safe, so there’s no need to do a bunch of causal studies ahead of time, and when they inevitably return nulls, they’d be hard to publish if there wasn’t something to react to.

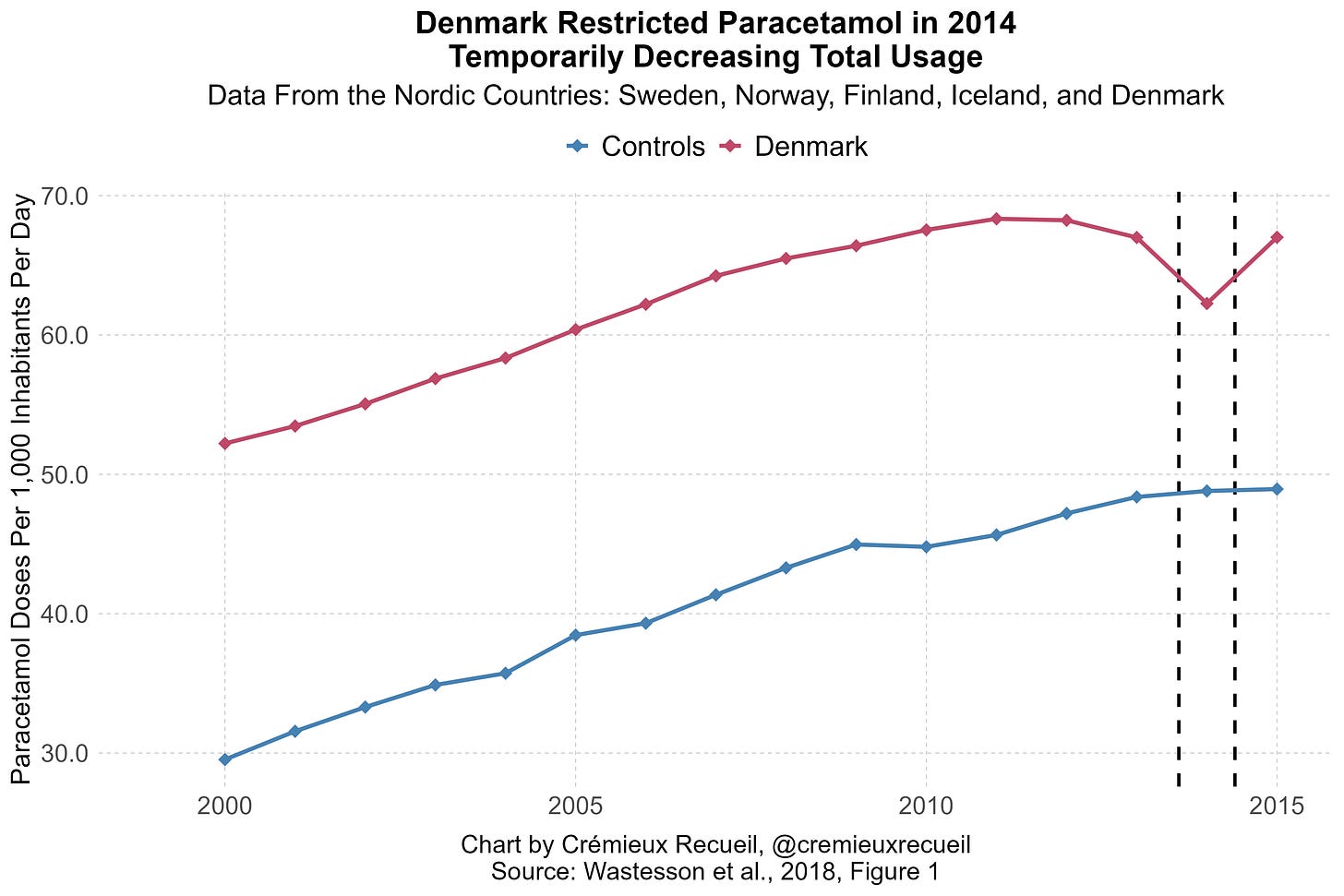

All that said, I’ve put together two additional pieces of causal evidence. One is an event-study based on Denmark’s acetaminophen regulations. I’ve described this here. Briefly, Denmark had a sizable, almost 10% dip in acetaminophen purchases when they made it harder to get high doses of the stuff.

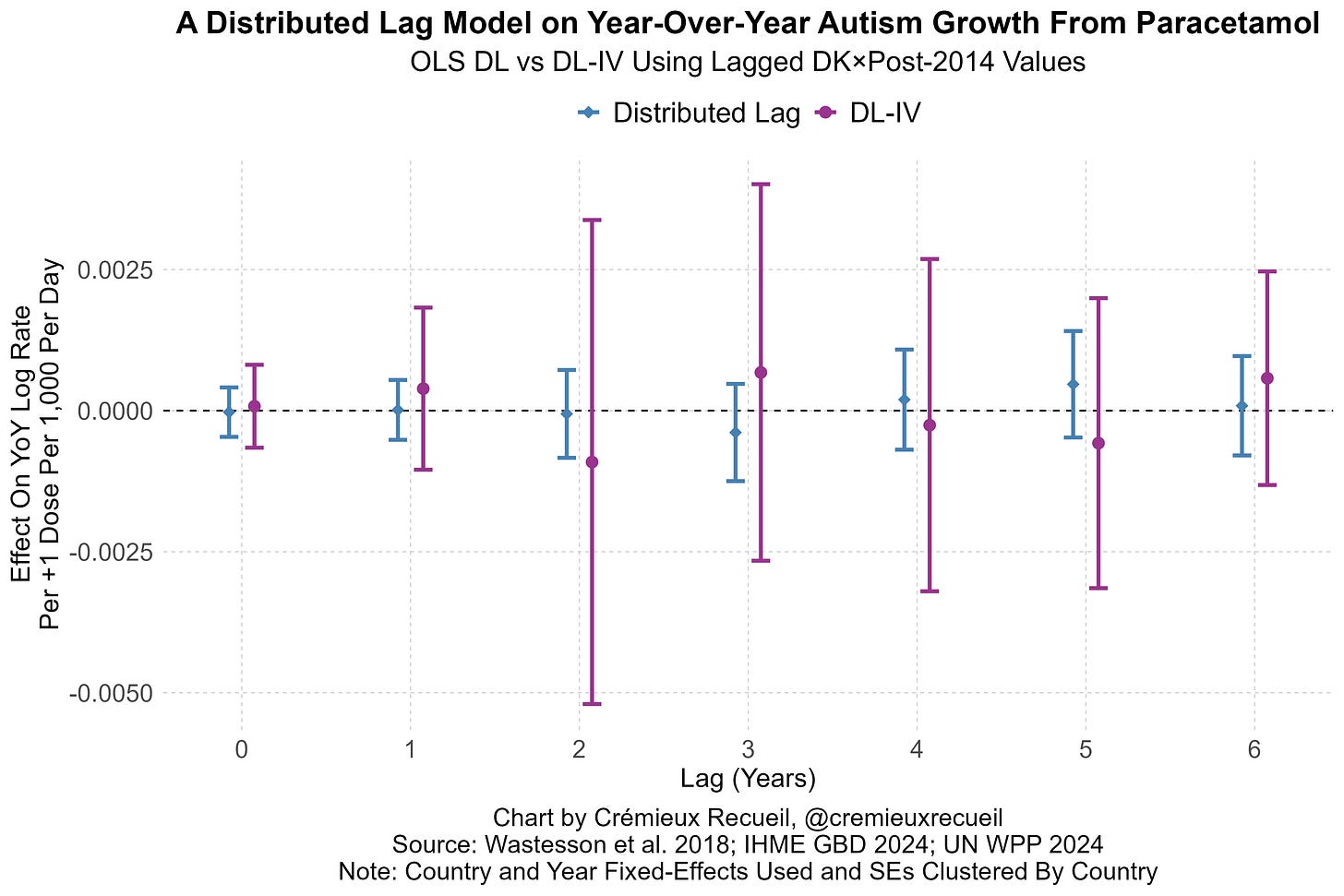

We can leverage this to assess what happens to prenatally affected birth cohorts years down the line. A basic distributed lag model applied to Scandinavian data returns no effect; combining this with an IV approach leveraging Denmark’s restrictions, we get larger standard errors, but also point-estimates around zero.

This evidence and the other evidence cited in the thread allow us to strongly reject the theory advocated by one of the people behind the Tylenol-autism announcement: that 90% of autism cases are due to acetaminophen. They allow us to reject other extreme theories, but they’re too underpowered to let us reject more reasonably theories. Luckily, the effect sizes we can reject using the sibling studies are very small, and there is extremely strong evidence in favor of the null in both.

The second piece of causal evidence I want to posit is based on Mendelian randomization. There are many variants we know that affect the pharmacokinetics of acetaminophen. For example, in UGT1A6. I used all the known variants for glucuronidation in UGT1A6, UGT1A9, and UGT2B15*2 and I used a lead reported near COMT, as well as a variant in CYP2E1 to target bioactivation to NAPQI, and alongside that, I looked at GSTM1 and GSTT1. I looked at variants in SULT1A1 to get at sulfation as well, but none of this separately or together threw up any sorts of warning signs. There was no relationship between factors affecting the metabolism of acetaminophen and autism.

But why would anyone be surprised by this? If you go into the Grove et al. GWAS’ supplementary information, not one of the gene-based associations or gene sets found to be enriched in autism has anything to do with xenobiotic metabolism. If you look through every SNP, you’ll notice that there are no hits near chr2 at 234.6-234.7 Mb, chr4 at about 69.5 Mb, anywhere near the right spot for CYP2E1 on chr10, and there are none on chr22 at all! Based on positioning alone, there’s nothing, not even LD; but if there was something strong here, it would show up. If there was even something small here, it would show up, but it doesn’t.

Where does enrichment take place? Not along UGT/SULT/CYP/GST/ABC transporter/glutathione pathways.4 Instead, the biological interpretation centers on neuronal function, exactly as we’d expect given what we know about neural development in autism cases.

Those who think acetaminophen is involved heavily or even slightly in autism need to contend with the strong causal evidence against their position and the fact that the only facts supporting their view are non-causal, statistically weak, and thus far always based on poor designs or premature (because it lacks statistical support!) and ultimately empirically untethered mechanistic theorizing. Moreover, they need to seriously contend with the fact that autism is extremely heritable, a large portion of cases are driven by de novo variants, diagnostic drift can fully explain the rise over time, and that exposures like acetaminophen usage are clearly genetically confounded.

Conflicts of Interest and Funding Lies

I’m going to keep this very short. Lawyer Nathan Schachtman, has written a good post on the people involved in this review and their lacking credibility. One particularly funny example is the coauthor Beate Ritz, who is to the lawsuit industry what Tobacco Institute scientists are to the tobacco industry.

More importantly, Schachtman noted that the review is being touted as NIH-funded. There is reporting that it’s an NIH study, but a review of the grants shows that they are unrelated to this topic area and the researchers have merely been supported financially by these grants for another purpose. This would normally not be a problem, but it is right now, because this erroneous funding claim is being used to suggest the review is reliable. After all, the NIH wouldn’t fund bogus research, right?5

The American public has been misled by false claims promoted by incompetent and malicious researchers who are the scientific equivalents of ambulance chasers. These researchers eschewed scientific rigor and serious thinking in favor of alarmist proclamations that will result in material harm to mothers and their unborn children for no more reason than that they would like to get paid as expert witnesses.

We have been lied to by trial lawyers and their paid witnesses. We have been told that this fraudulent review is “NIH-funded” (a lie) and “Harvard-backed” (a lie and a misunderstanding about author affiliations signaling university support), and the fact that their conclusions are entirely in the wrong and the authors are documented promoting nonsensical conclusions is being swept aside and covered up by appealing to the false authority that one of them obtains from being a Dean at Harvard.

But anyone with eyes can see that the American public is being lied to and anyone with a memory better than a goldfish’s can remember that just a few weeks ago, Harvard was being portrayed as the HQ for this administration’s enemies. Now that the HHS is promoting harm, and presumably since they have no real arguments in support of the link between acetaminophen and autism, Harvard is respectable again. Curious!

P.S. The HHS said they would explain autism by September. They were provided with data that showed what a proportion indistinguishable from all of the rise in autism diagnoses was attributable to—diagnostic drift and its accouterments—and they ignored it in favor of promoting hurting people by promoting fraudulent work.

Something that the judge did not notice about this study is that it generally did not reach significant results in the total cohort. The focus on the sibling study by Baccarelli—despite his criticizing better sibling studies—seems to be driven by the significant results, whose adjusted estimate p-values in all but two cases ranged between 0.01 and 0.04, a sign of p-hacking. In the total cohort, there were three marginally significant results (p’s = 0.01, 0.02, 0.03), one significant result that would not survive correcting for multiple comparisons (p = 0.004), and four that are significant, among many that are not. The four clearly significant results were for Externalizing and Emotionality, and only one significantly held up in the sibling pair analysis (Externalizing), albeit now seemingly not between no and moderate exposure levels.

Their statement and the following review also shows that, instead of meta-analysis—which would’ve been fine and would’ve clearly shown that larger, better studies yield smaller effects, consistent with publication bias—they prefer ‘vote counting’ studies. Basically, they think a better methodology than quantitative review—which would’ve delivered small enough ORs that all PAFs would be tiny—is to do a ‘narrative review’ amounting to little more than repeating their opinions by dismissing studies they dislike and lauding studies they do like.

Their focus on statistical significance is in support of this goal and it effectively places publication bias-afflicted studies over more careful and less corrupt work. As an aside, my focus on statistical significance here is something I’ve explained in my article on the suspiciousness of marginal p-values. Go check it out!

Notably, because Trump kept mentioning postnatal exposure, this study found no association whatsoever with postnatal exposure. Also, this study suggests that acetaminophen cannot explain the rise of autism because there’s no effect on autism without ADHD.

The same is true for ADHD, but I didn’t discuss it here since the topic is really autism and ADHD should be secondary.

Note: DOGE cut tons of bogus research.

The work, thought, and knowledge reflected in this post yet again reminds me why I’m a paid subscriber.

There is a concurrent article at John Leake from FOCAL POINTS that is diametrically opposed to this one. Some of the illogical comments from the author and followers are sometimes comical. To me, the author and his followers are dogmatic.