Let's Not Overstate Support For Violence

Recent polling suggests left-wingers support political violence at extremely high rates. Those results need to be taken with a heaping of salt.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

Millions of people have recently been exposed to a simple, shocking idea: large numbers of left-wing Americans support political violence.

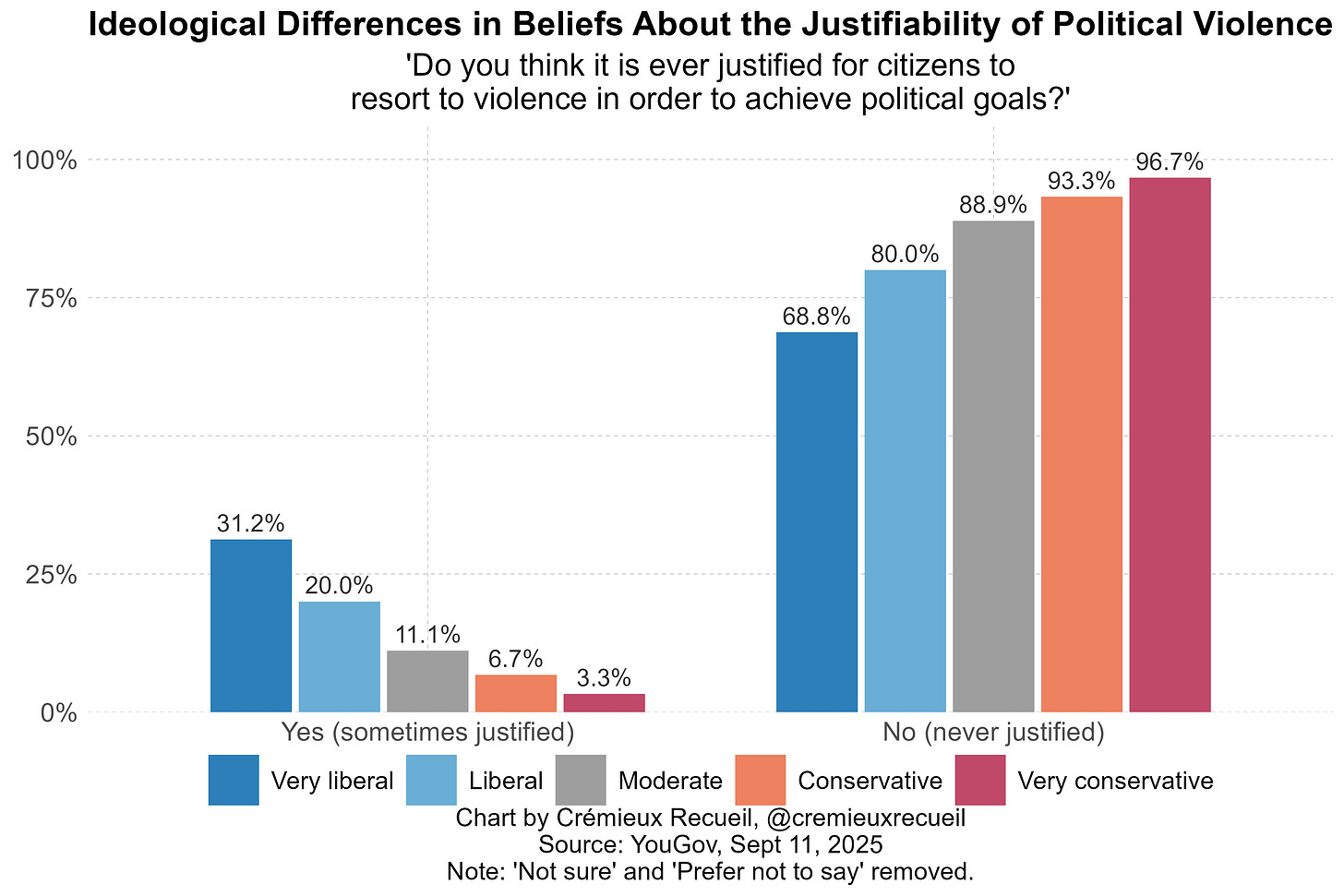

You might’ve seen this finding illustrated in charts like this:

On its face, this is compelling. It is rightly taboo to support political violence, as political violence signals the end of normal politics, the breakdown of democracy, the failure of liberalism, and a force that our world order should struggle against because it is just that harmful. No reasonable person wants civil war or revolution. So when 30% of so-called “very liberal” (i.e., leftist) and 20% of merely “liberal” people say they support political violence, that’s serious and it needs to be treated seriously.

But let’s not take this too far. We probably don’t need to start mass-surveilling left-wingers to prevent them from violently organizing. We should instead make an effort to understand surveys and what they can tell us about the world we live in.

Biased Responding

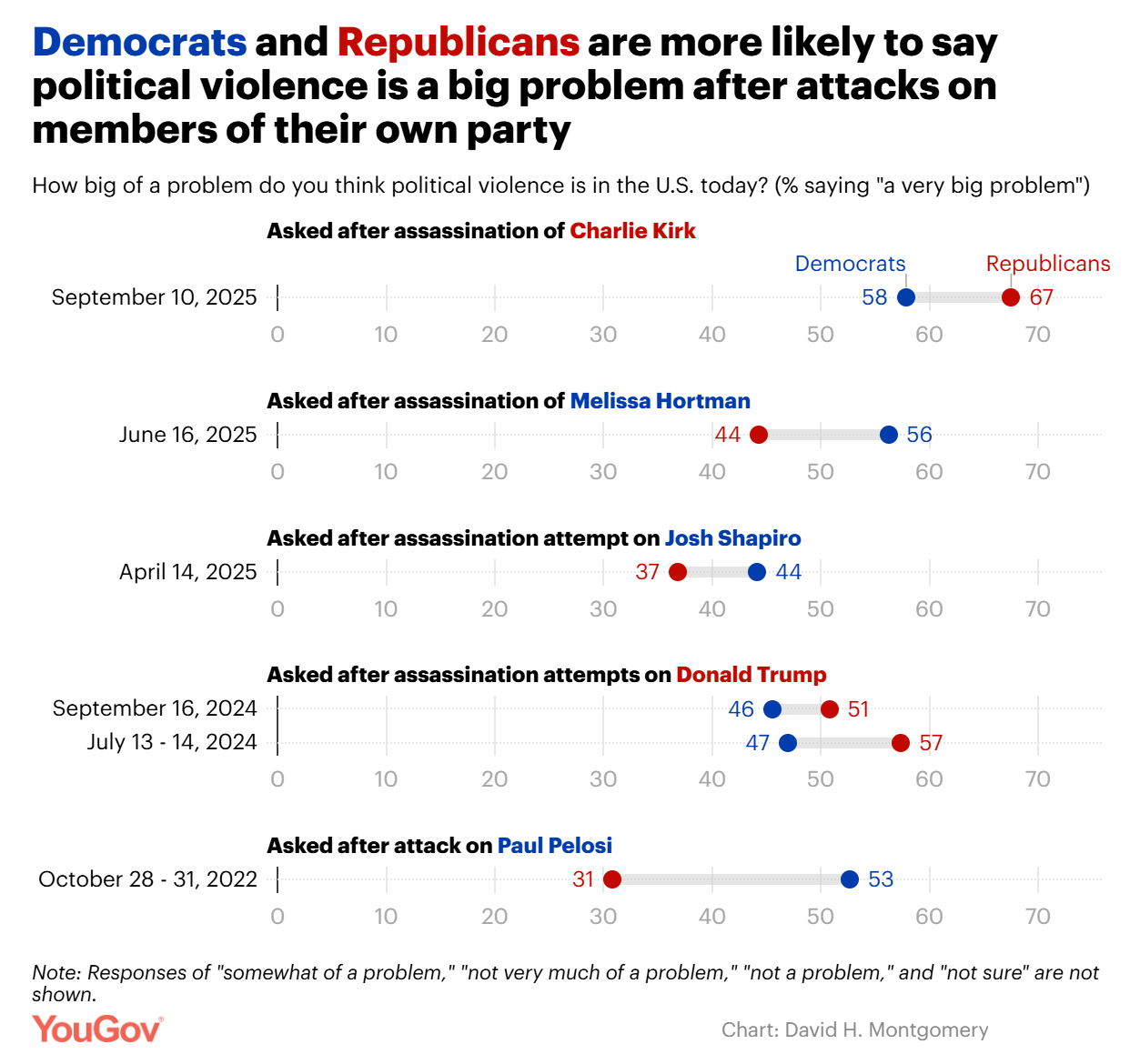

Firstly, this is not a consistent finding. The pollsters responsible for that chart have been asking the same questions about political violence since 2022, and they’ve timed surveys to be after major incidents of political violence. The political valence of concern about political violence shifts based on the target of attacks. After the assassination attempts on President Trump, Republicans were more concerned; after the attempt on Pennsylvania’s Governor Shapiro, Democrats were more concerned.1

What we see in polling data is that people express greater concern about and disapproval of political violence when it’s happening to people perceived to be on their side. We don’t know if the effect is systematically larger for one or the other party in the U.S. or elsewhere, but we do know that this happens reliably enough for major incidents or when people are prompted accordingly.

Therefore, it’s reasonable to speculate that people are not providing pollsters with accurate statements of principle. They are more likely engaging in polarized responding. They might be doing something like bashing the other side, following the leader, or otherwise providing socially desirable responses. Downgrade your evaluation of the seriousness of people’s survey responses with this in mind.

Disengaged Responding

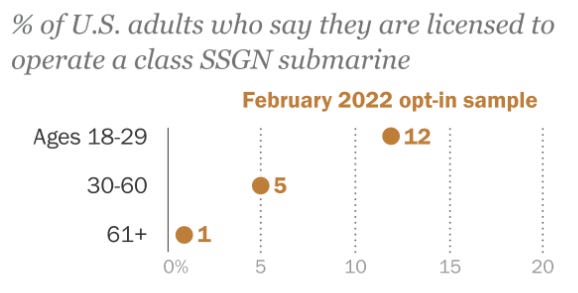

Secondly, do you operate a nuclear submarine? Fewer than 0.01% of Americans are, but if you ask opt-in samples, you can easily overstate that number. Pew found that, in a sample from 2022, every age showed a massive exaggeration of the rate of being licensed to operate nuclear submarines, from 1% among those aged 61+ to 12% among those aged 18-29.

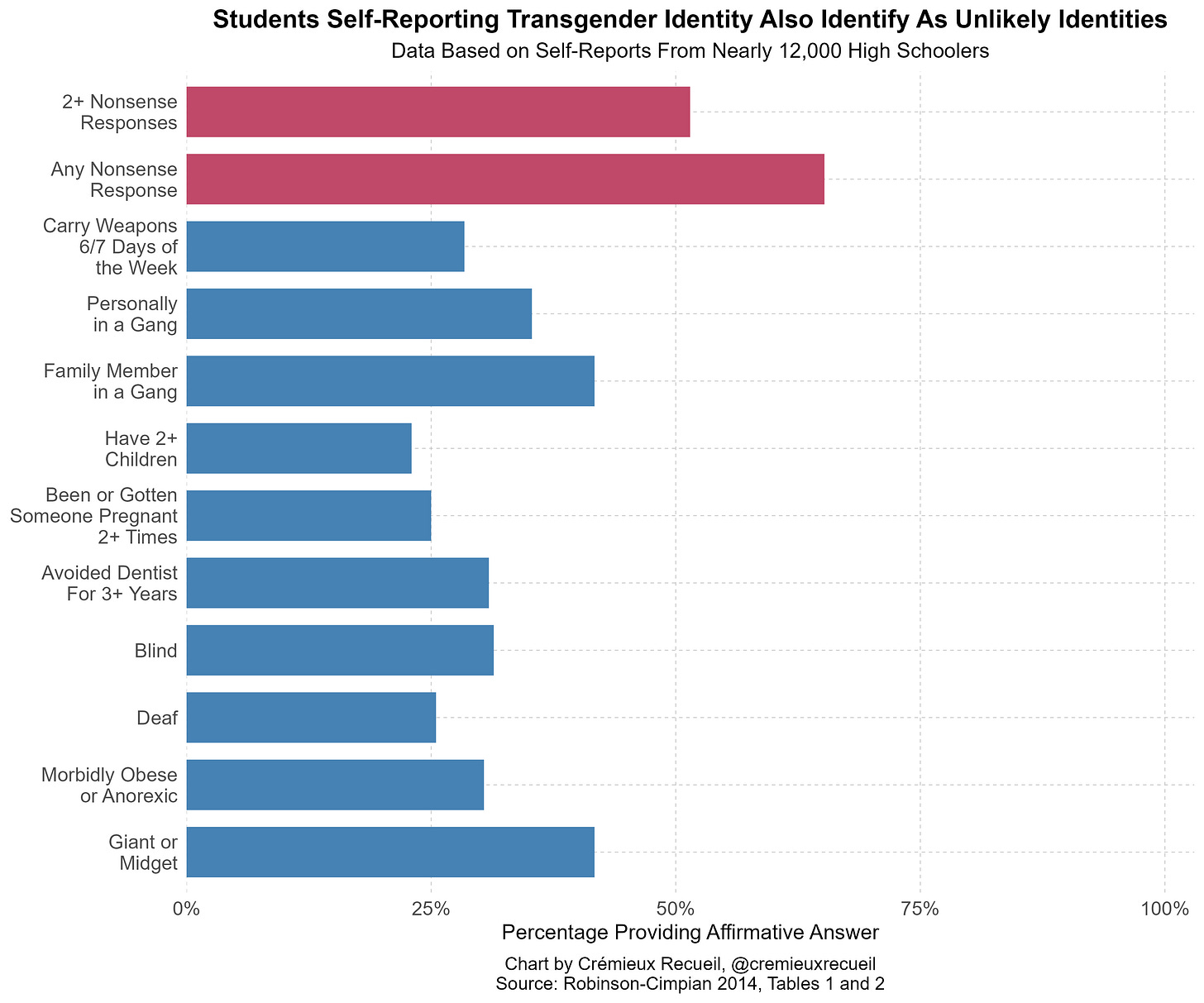

As of March 2025, about 1 in 1,000 Americans are in the Navy, and only a small share of that number are licensed to operate a nuclear submarine. These reported polling numbers are impossible to generate with a representative sample responding honestly, but they are not out of the ordinary. Consider what happens to polling about being transgender among high schoolers. They think it’s funny to lie on surveys by saying that they’re trans and a number of other things. Accordingly, students who self-report that they’re trans also shockingly likely to report being blind, armed, 7-foot-tall obese crackheads with an inveterate aversion to the dentist. People just say things.

Unfortunately for those of us who want to avoid their peers freaking out about the topic of political violence, people also ‘just say things’ on surveys about it.

My favorite study on this was a survey study that did two things:

Gave survey respondents questions that weren’t ambiguous.

Provided respondents with questions that kept them engaged.

The first issue has to do with how insufficient definition in questions likely upwardly biases reported support for political violence. In an era where everything is violence, this is a very salient concern.

The question “How much do you feel it is justified for [respondent’s own party] to use violence in advancing their political goals these days?” doesn’t explain to participants what “violence” means. The conditional average for Pr(support partisan violence) subsumes very different definitions of violence. Some participants think it’s about assault, and others think it’s about murder. Every reasonable person thinks murder is worse than assault and there’s a deservedly stronger taboo on murder than on assault. But when we see statements like ‘X% of the the left/right support political violence!’ what those people support is not addressed, everything gets put under a broad label.

It’s important to handle this conflation of different types of violence because it’s debatable whether some forms of violence qualify as political violence or fall under society’s taboo on political violence. As the authors note:

It is impossible to know, from existing responses to vague questions, whether respondents support severe, moderate, or minor forms of violence, which could range from support for violent overthrow of the government to minor supporting assault at a local protest.

The second issue has to do with survey respondents being insufficiently reflective when it comes to complex questions. For example, the question “How much do you feel it is justified for [your party] to use violence in advancing their political goals?” might include the response levels “Not at all,” “A little,” “A moderate amount,” “A lot,” and “A great deal,” and anything above “Not at all” might wind up being recoded as support for political violence. Without a truly neutral option or an option to say they “Don’t know,” some participants will wind up frustrated or otherwise disengaged, they’ll satisfice and end up inflating the extent of reported support for political violence because most of the available options are ‘consistent with’ support.

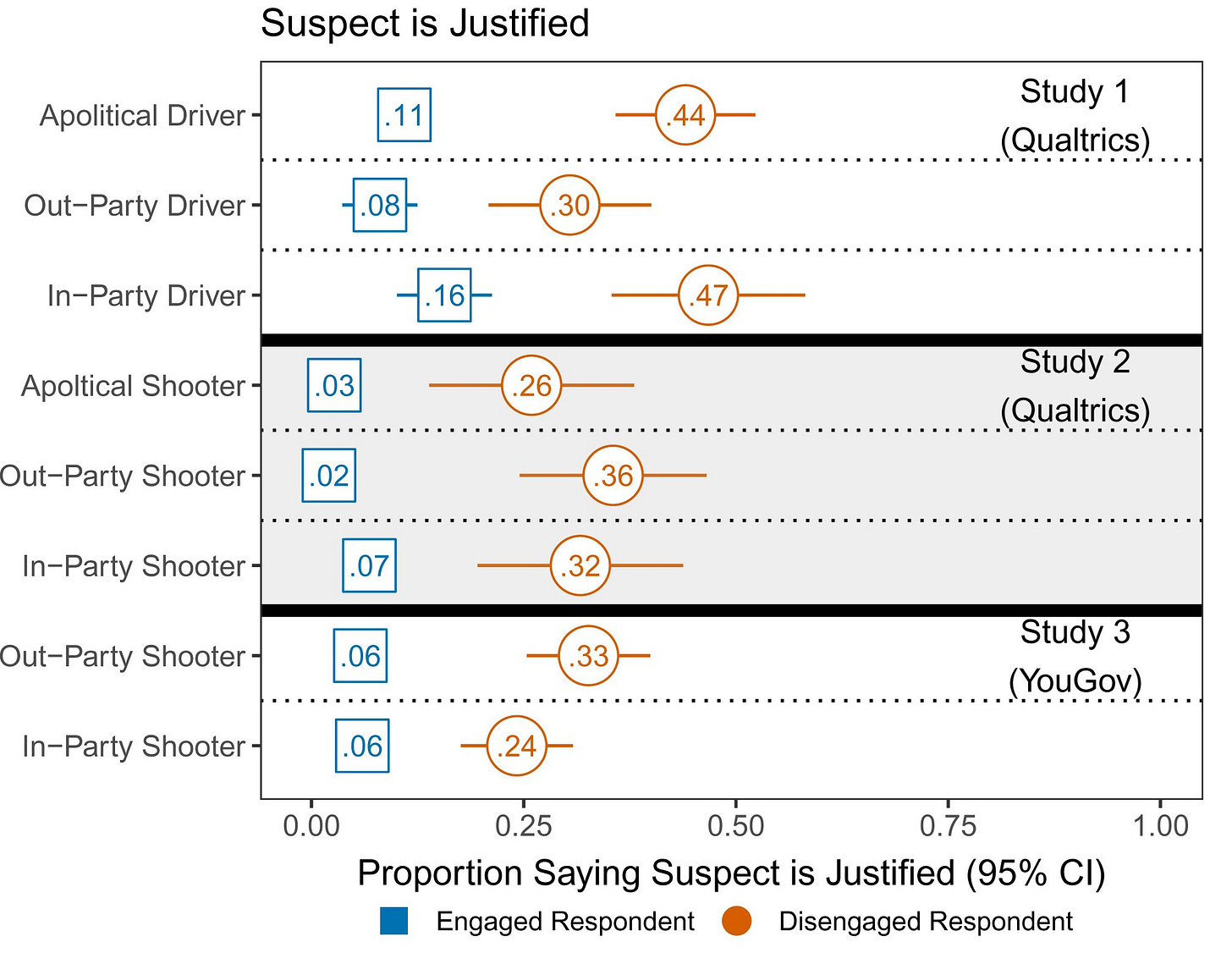

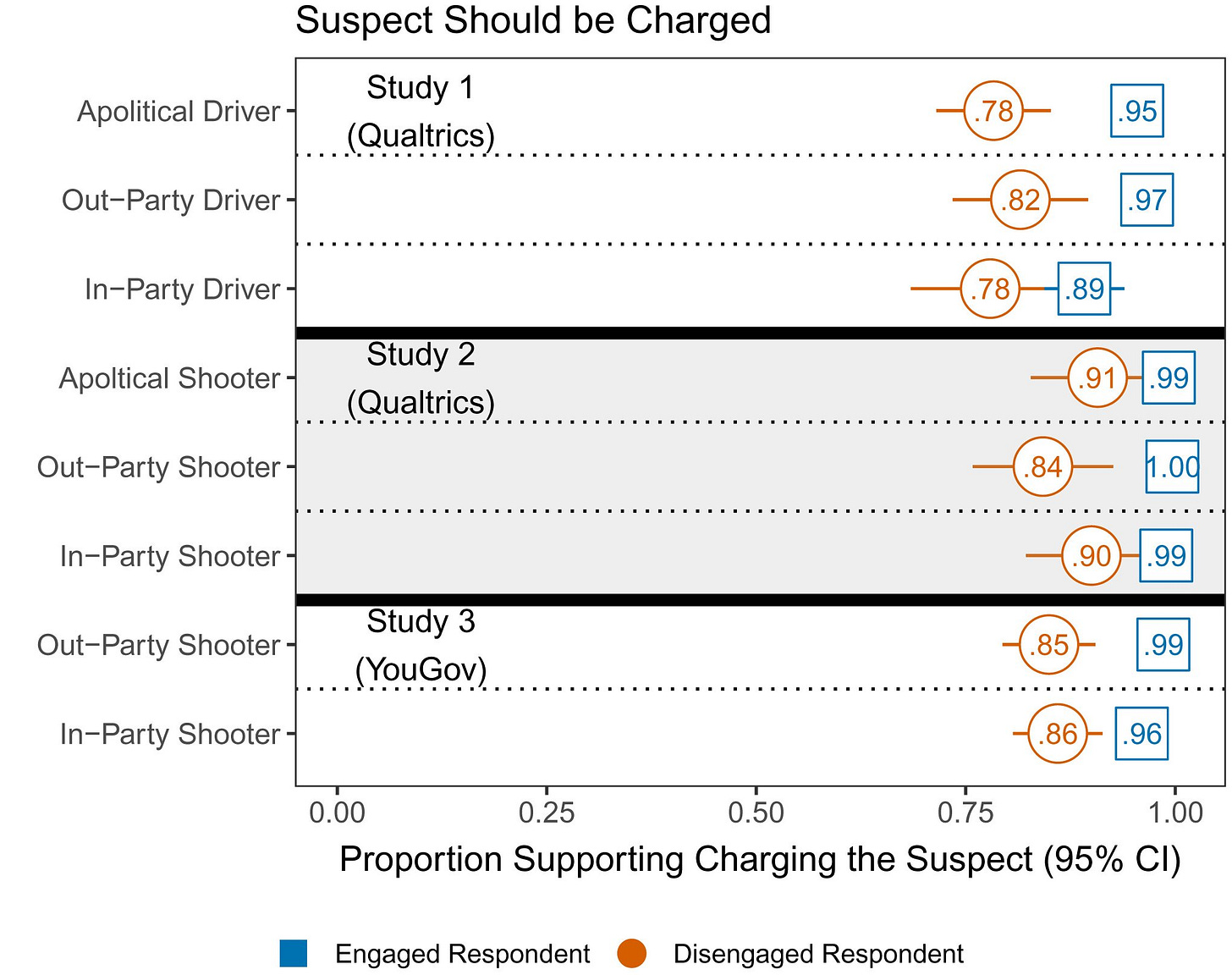

By designing a better survey, the authors were able to plausibly account for at least some of the influence of these issues. For example, across three sets of surveys conducted using two different surveyors, they found that people were far less likely to claim that a suspected violence perpetrator was “Justified” when the survey plausible did a better job keeping them engaged. This engagement gap accounted for the vast majority of the belief that violence suspects were justified.

Similarly, keeping survey participants engaged increased the extent to which they said suspects should be charged with crimes.

When you ask the questions appropriately, almost all people seem to agree that political violence is bad and should be punished. The authors also quantitatively assessed this by asking people about the sentences they would propose for the suspects of different things that might be forms of political violence. This finding was clear: support for political violence is lowest for the most severe forms of crime. This meant that there was less support for murder than for assault with a deadly weapon; for arson than for assault; for vandalism than for protesting without a permit.

Unfortunately for everyone who wants to really understand support for violence, these biases not only lead to overstated support for political violence, they also inflate correlations with support for political violence. For example, scores on a short aggression questionnaire were predictably related to support for political violence—that is, more aggressive people were more likely to support violence. Go figure! However, accounting for engagement and using more precise measures of aggression, the strength of the relationship became about four-times smaller.

Our goal is not to argue that there is no support for political violence in America. Recent events demonstrate that groups of American extremists will violate the law and engage in violence to advance their political goals. Instead, our purpose is to show that, when attempting to estimate support for political violence among the public, care and precision is required. Generic and hypothetical questions offer respondents too many degrees of freedom and require greater cognition than a sizable portion of the population will engage in. [Emphasis mine.…]

Our results show support for political violence is not broad based and is [many times less common] than… previously reported. The public overwhelmingly rejects acts of violence, whether they are political or not. [E]xtant studies have reached a different conclusion because of design and measurement flaws.

Real Data

Gathering data on support for political violence is fraught. Gathering data on actual acts of political violence has been even worse. Recent efforts to classify this or that incident as violent, let alone to assign it to one or another group or side have given rise to infinite methodological critiques for what might just be a ‘hard problem’: What constitutes political violence? How can you say who’s responsible? What’s uncounted and why?

Test yourself: were the BLM George Floyd riots left-wing political violence? When the Latin Kings and Aryan Nation engage in race-based conflicts in prisons, is that political violence? And to what side do these things ‘belong’? If you’re honest with yourself, you should be willing to admit that these questions don’t have unambiguous answers. There’s too much to legitimately debate about these efforts, so there will never be a quantification that leaves every reasonable party satisfied enough to cleanly tally up support or responsibility for political violence.

I’m going to end by reemphasizing something: political violence is wrong. Rioting is wrong, terrorism is wrong, revolution is wrong, assassination is wrong, prejudicial discrimination on the basis of irrelevant characteristics is wrong, and so on and so on. It’s a real issue if we can’t all agree on at least these things.2 Let’s not distract from that.

Do note: There is a major issue of awareness. Practically everyone knows who Donald Trump is, but far fewer are aware of someone like Melissa Hortman, and awareness seems related to political sides, where Democrats are more likely to be aware of who Hortman is than Republicans are. Even President Trump was unfamiliar with her when a journalist asked him about her assassination in the days following Charlie Kirk’s assassination.

To preempt unnecessary quibbling—which really just makes one of my points—the phrase “murder is wrong” is reasonable and generally accepted, even if “murdering Hitler to prevent the Holocaust” is also reasonable and generally accepted. The overwhelming majority of normal people understand the difference and there’s no need to discuss it.

Cremieux Recueil getting people to think critically about survey results always gets a "like" from me.

I remember from the 2-year stint I spent working in the survey statistics, seeing those nonsense answers. Especially in the age of self-identification of gender, etc., we would see respondents with write-in answers of "Attack Helicopter" or "Batman" for their gender. Higher quality surveys will try to disqualify these respondents or at least filter out the obviously bogus responses. I doubt the mass-produced Gallup/Pew/YouGov style polling does, but I never worked with those kind of firms specifically.

This is a problem that seems to be getting worse as survey response rates plummet and surveys resort to online survey modes. A lot of people are brain dead in front of a screen from being constantly in front of screens.

“ This finding was clear: support for political violence is lowest for the least severe forms of crime. This meant that there was less support for murder than for assault with a deadly weapon; for arson than for assault; for vandalism than for protesting without a permit.”.

Lowest for the least, or lowest for most?