The Myth of the Sommelier

Is there an art to wine tasting? Do the best tasters really know best?

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than three hours to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

My friend sold his company, made his millions, and now he’s—suddenly!—a “wine expert”. Practically, that means that when he hosts parties, I have to bring a more expensive housewarming gift. But it’s also motivation for me to write up my feelings on sommeliers and their wine discriminating abilities, or lack thereof.1

Judgment of Paris

When I mention “Judgment of Paris”, your first thought probably has to do with the Trojan War if the term means anything to you at all. But instead, I’m referring to an infamous wine competition that took place in Paris, France in 1976.

In the oenophile (wine lover) version of the Judgment of Paris, a British merchant invited France’s top wine tasters to judge two flights of wine: white Burgundies vs. California Chardonnays and Bordeaux vs. California Cabernets. At the time, the reputation of California wines was nonexistent; to quote the man behind the contest: “California wine was not viewed. California wine did not exist.” Nevertheless, going in blind, the raters picked the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay as the top of the whites and the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars S.L.V. Cabernet Sauvignon as the top of the reds—both are California wines.

This was an upset. Before 1976, ‘serious’ fine wine was widely assumed to be French, and French alone. The Paris result publicly punctured that belief, catapulting Napa Valley onto the world stage and accelerating investment, plantings, and global respect for New World wines. TIME magazine’s report by George Taber (which later became the book Judgment of Paris) popularized the story and museums now display bottles from the tasting, including the Smithsonian, which has displayed Montelena’s 1973 for quite some time. Quoting Taber:

The French bamboozled the world into thinking that only in France could you make great wines, that only in France did you have the perfect climate, the perfect earth, the perfect grapes. France was on a pedestal. France was alone.

The result was clear, but immediately contested. The oenophile community would not readily renounce their belief that, in wine, France was supreme. Replications took place. First, the San Francisco Wine Tasting of 1978 pitted another group of blind evaluators to the task of judging French versus Californian flights, and again, Californian wines came out ahead. The Judgment of Paris was evidently not a fluke!

Many oenophiles were still unsatisfied. Now, they argued, French wines aged better. Ten years after the original competition, the French Culinary Institute conducted another tasting. Eight judges blindly went at it again, and California vineyards still trounced their French counterparts. In the same year, Wine Spectator replicated this result even more decisively, with California wines ranking solidly ahead.

Still, committed oenophiles could not be easily repudiated of their belief that French wines, if not better, would be better.

Thirty years on from the original competition, tasters were assembled on both sides of the Atlantic, many of whom had judged in the original competition, and some of whom reportedly expected America’s downfall. But there was no downfall: thirty years after the Judgment of Paris, California wines won again! What made this more impressive is that three of the Bordeaux wines that were trounced were identified by the highest authority on Bordeaux—Le Conseil Interprofessionnel du Vin de Bordeaux—as the best vintages of the previous half-century and the fourth was rated as “very good”—a judgment supported by L’Office National Interprofessionnel des Vins.

The Judgment of Paris was a watershed moment in the world of wine. Cheap, unknown, and comparatively inexpensive California wines from upstart vintners had defeated elite French bottlings derived from generations of tradition, permanently resetting the starched views of critics, collectors, and consumers about the origins of great wine. But more importantly for us, they showed that cultured, haughty oenophile prejudices were bereft of substance; they laid bare the reality that the refined judgments of the top sommeliers were lacking in predictive power.

Les Habits neufs de l’empereur

Refined, practiced, and intergenerationally transmitted knowledge is something oenophiles take pride in. The art, style, and culture of wine is ancient, and mastery takes a lifetime, at a minimum. At least, that’s how ‘experts’ want the craft to be perceived. In reality, the Judgment of Paris is not exceptional; wine aficionados have repeatedly been taken for fools.

Wine Spectator is considered one of the wine world’s premiere lifestyle magazines. Its editors review hundreds of wines per issue and they organize banquets, philanthropic efforts, festivals, and wine tours across the globe to promote viticulture, oenology, and the love and knowledge of all things wine. Wine Spectator is, by all accounts, an institution supporting numerous other important institutions in the world of wine.

But the veneer of credibility these reviews, the efforts, and the recognition it receives provides Wine Spectator is fragile. Beneath the surface, the grapes are sour.

In 2008, writer Robin Goldstein launched the restaurant “Osteria L’Intrepido.” Headquartered in Milan, Osteria paid Wine Spectator a $250 fee to compete for one of their honors, the Award of Excellence certifying the quality of their wine selection.

But there were two problems. Firstly, the restaurant did not exist. It was a farce whose sole proof of existence was the piddling internet presence Goldstein had built it and the form and fee Goldstein had provided Wine Spectator. Secondly, Wine Spectator merely judged the wine list Goldstein sent them. Amusingly, said list was populated with wines that Wine Spectator had previously described as among the worst.

To wit, Osteria’s menu included a wine that Wine Spectator had given 65/100 points—a failing grade—and described as “not clean” and like “stale black licorice.” It included a wine they had previously judged was like turpentine—74 points—and another they dubbed “swampy”—64 points. In fact, every entry on the menu was a vintage that Wine Spectator had previously panned. Despite the obvious nature of the ruse, Osteria L’Intrepido was ushered into that year’s batch of winners.

This is far from the only time when wine institutions have been hoodwinked.

Counterfeiter Rudy Kurniawan blended and relabeled wines from his LA home, selling millions in fake high-end wines until years had passed and an FBI raid finally got him—not the ‘discerning’ palates of his picky customers. Similarly, Hardy Rodenstock duped prominent collectors into believing he had obtained bottles from Thomas Jefferson’s personal collection. He was only caught due to a personal crusade by famously disagreeable billionaire Bill Koch after facts failed to line up.

In “Pinotgate”, French suppliers sold 18 million bottles of Merlot and Syrah as “Pinot Noir” to American customers and tasters, and no one noticed. The controversy broke when French investigators saw that the wine merchants involved were selling more than the whole region produced—a clear sign that something was wrong! But again, purchasers and reviewers were caught unaware.

In “Brunellogate”, batches of Italy’s Brunello di Montalcino were found to have been diluted with grapes besides Sangiovese, the only grape they’re permitted to be made from. This controversy was noticed for similar reasons to Pinotgate—namely, fishy paper trails. Registry audits exposed mismatches and surveyors went out and found that some vineyards recorded as Sangiovese actually contained other varieties. This knowledge resulted in probes, investigations, raids, vineyard quarantines, and the seizure of millions of wine bottles. But once again, this was not at the behest of the refined palates of reviewers.

After the news of Brunellogate broke, some critics like Kerin O’Keefe might have helped the field to save face, claiming that Brunellos were suspect for several years prior to the controversy, but it’s hard to make much of this when polluted Brunellos were frequently lauded in the interim and even won several awards.

I have no doubt some of you will be familiar with grapes like these, but for the majority who are not, let me confirm what you’re seeing: those grapes are rotten. That’s a good thing! What you’re seeing there is “noble rot”, which makes grapes harvested late in the season taste even sweeter if the rot is properly exploited.

These rotted grapes make for excellent dessert wines. Unfortunately, harvests couldn’t keep up with the demand for the sweet stuff. But never fear: an intrepid Austrian innovator stepped up with a simple proposition: Why not add diethylene glycol?2

A small amount of DEG—a chemical closely related to antifreeze (ethylene glycol)—helps to mimic the luscious late-harvest taste of the highest quality dessert wines. After producers discovered this One Simple Trick, millions of gallons of DEG-adulterated wines flooded the market and flew off the shelves. Several even received rave reviews! But though DEG makes for tasty wines, it can be deadly in the right quantities. At least one bottle was found to contain enough to kill if consumed in a single sitting (luckily, there were no reported injuries, let alone deaths).

Sommeliers can allegedly tell you all about wines, from the time of the seasons grapes were planted in, to the regions they came from. They’re supposed to be able to suss out acid, tannin, and alcohol balance, typical aromas, climate signals, oak aging, malolactic fermentation, and lees stirring cues, new versus neutral oaks, oxidation versus reduction, residual sugar and approximate alcohol, sparkling methods, smoke taint, cork taint, vinegar and nail polish remover, sulfur faults, and more. They’re also supposed to be intimately familiar with different vintages, regional wines, and so on. And yet, no one caught the epidemic of mass DEG adulteration; authorities, magazines, connoisseurs, and reviewers even gave adulterated wines awards and in a rare few occasions, even praised their uniqueness! (Perhaps that’s to their credit.)

DEG adulteration was detected through routine market surveillance picking up large quantities of DEG in supermarket stock in Stuttgart. Broader screenings followed and quickly identified many Austrian bottlings and some blends bottled in West Germany that contained DEG. Product withdrawals, warnings, and higher standards followed.

Let me be clear. There are hundreds of different large-scale wine scandals that suggest the institutions responsible for reviewing, rating, and certifying wine don’t deserve the reputations they pride themselves on. The authorities responsible for training sommeliers and informing the interested public about oenology are also bankrupt. Many wine scandals indicate credulity rather than expertise; others suggest that the skills sommeliers and their like have claimed to hone are limited at best and in so far as those skills inform the refinement of their palates, those skills and that refinement may be as good as nonexistent and perhaps little more than prejudice.3

My point is, the emperor has no clothes. Now, let’s move beyond anecdotes.

Experts at What?

In 2003, California Grapevine tracked 4,000 wines across fourteen competitions. Of those 4,000, some 1,000 received a gold medal in at least one competition and then went on to fail to place in any of the others. Why?

Is it because panels of judges vary that much? If reviewers and sommeliers are to be believed, that should not be possible—there should be standards!

Is it because different bottles vary that much? If producers are to be believed, that should also not be possible, and there’s a good case they’re right because there are production standards that should keep ‘the same’ wines similar across bottles.4

Is it because of luck that other wines would outcompete them just-so? Highly unlikely!

With 4,000 bottles across fourteen competitions, where 1,000 received a gold medal in at least one competition and failed to place in others, the implied per-contest gold rate p is 1— 0.75^¹⁄₁₄ or just over 2% under independence.5 With 4,000 bottles, that’s 81 of these golds per contest on average. Let K ∼ Binomial(14,p) be the gold count across fourteen contests for a bottle.

Or in other words, among 4,000 bottles, you’d expect the number of bottles receiving a gold exactly once to be 4,000 × 0.217 ≈ 868 (σ = 26, hence the approximate symbol) and the number receiving a medal two or more times to be 4,000 × 0.033 ≈ 132. Take those 1,000 gold winners and throw them in thirteen other contests and the chance that they win at least one other one is

So you’d expect about 234 of the 1,000 to show up with another win somewhere else with a small σ of about

So about 766 would be unique to a given contest. If we observe multiples and the counts are roughly 200-260 overlaps, that’s plausible. But the real number of overlaps is much smaller, so that’s not plausible. Moreover, if judges are actually reliable—that is, the independence assumption is wrong—then it becomes even less plausible.

Consider the extremely conservative scenario where judges are only 50% reliable, meaning that there’s a huge amount of non-wine variance in wine judgments. We can model this as a beta-binomial including an intraclass correlation ρ = 0.5 and assuming each bottle has its own underlying “gold probability”, pᵢ which holds across contests. Mathematically, we have:

The mean per-competition gold probability averaged over bottles is thus

So across 4,000 bottles, we should have about 346 of these golds, not 1,000 if judges are even 50% reliable. Calculate out our probabilities again for K = 1 and K ≥ 2, and now we get about 6.5% and 18.5% of bottles. That means that across 4,000 bottles, you’d expect about 261 to get a gold once and 739 to get two or more, making the observed overlap across contests inconsistent with expectations if judges are even 50% reliable. If judges are more reliable, then the results are that much more damning.6

Or to make this simpler, given 4,000 bottles and fourteen contests with 25% ever winning a gold, the implied per-contest gold rate under independence is about 2%. That predicts about 870 bottles winning exactly once and about 130 winning multiple times, and that roughly a quarter of any contest’s winners should show up with a gold somewhere else. The observed pattern—basically just 1,000 “one-off” winners with very little overlap across the other thirteen contests—is many standard deviations away from those expectations. And if judges are even moderately reliable (consistent in their judgments of different wines across contests), then repeats should be much more common than under independence. So, the data are inconsistent with any reasonable level of judge reliability and strongly suggest unreliable criteria or noise rather than robust, repeatable quality judgments.7

It seems very likely a priori that wine judges are unreliable, and that throws the whole enterprise into question. The go-to citation on this subject evaluated judges at the California State Fair, a massive wine competition involving thousands of wines being served to more than a dozen panels of judges. The awards issued at the Fair are thought to be more than worth the entrance fee: top-rated wines are widely believed to get a sizable sales boost and they definitely get public recognition! But if the judges are unreliable, that should inform us about the worth of those medals.

In this study, the judges for the years 2005 to 2008 were systematically assessed. In each panel, the wines that judges were blindly issued contained triplicates (i.e., three identical pours) poured from the same bottles so we could see how consistent their ratings were for the exact same wines from the exact same bottles.

How consistent were they? Not very. Only 10% of judges consistently placed the exact same bottles in the same medal range (i.e., within four points in a twenty-point scale). Another 10% awarded scores that were twelve points apart or worse. The typical level of consistency was an eight point gap, or the difference between a high bronze and a low gold medal placement. Perfect consistency was only achieved 18% of the time, but almost always for wines that judges entirely rejected—obviously bad wine!

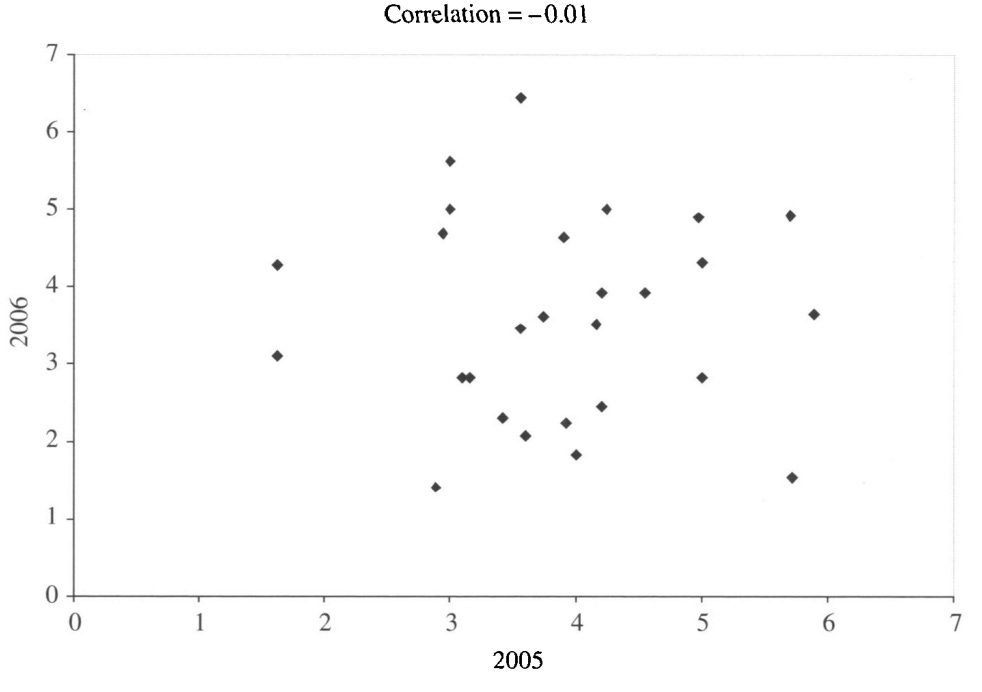

This was repeated across years, too. Judge variance in one year did not predict their variance the next year at all.

An ANOVA of the results suggested something disheartening:

In 30 cases, about 50 percent, the wine and only the wine was the significant factor in determining the judges’ score. For the remaining 50 percent of the panels, other factors played a significant role in the award received… Ideally, an examination of… judging panels… would show… wine and only wine is the determinant factor. How can one explain that just 30 panels, less than half, achieved those results? The answers are judge inconsistency, lack of concordance—or both.

The author of this research followed up on this using the Grapevine data I mentioned earlier. Their conclusion was the same as the one I pieced together based on a naïve understanding of the structure of the data. That is: judges are radically unreliable. The highest correlation between any pair of festivals was 0.33 and the median was just 0.10:

(1) there is almost no consensus among the 13 wine competitions regarding wine quality, (2) for wines receiving a Gold medal in one or more competitions, it is very likely that the same wine received no award at another, (3) the likelihood of receiving a Gold medal can be statistically explained by chance alone.

If the wine experts in charge of judging at these competitions were really expert and they deserved the high reputations oenophile stereotypes suggest, then wine and wine alone would influence their judgments. No judge ever recorded has met this bar.

Empirically, researchers have attempted to quantify expert consistency in terms of the statistic kappa, a measure of agreement over time. Using data on triplicate pours from the same bottles, a kappa of 1 means that every rating a judge gives is consistent. This is trivial to achieve if all the judgments are that wines are all good or all bad, but judgment distributions are not like this, so we don’t have to worry about that, and we don’t observe it in any case. A kappa of 0.70 is what psychologists would dub a “substantial”—more than moderate, less than perfect—degree of agreement.

For an expert judge to achieve a kappa of 0.70 across four bottles, they would have to give their triplicate pours the same exact ratings in two out of four bottles, and they would only be able to disagree once per pour. That means that if they have four bottles, an acceptable set of ratings is Bronze-Bronze-Bronze, Silver-Silver-Silver, and something like Bronze-Silver-Silver and Silver-Gold-Gold. If they had a judgment like Bronze-Gold-Gold, this would be too large a gap and their kappa would drop below 0.70. In other words, expertise leaves little room for inconsistency. But as we’ve seen, judges are incredibly inconsistent:

What do we expect from expert wine judges? Above all, we expect consistency, for if a judge cannot closely replicate a decision for an identical wine served under identical circumstances, of what value is his/her recommendation? […] Based on a weighted kappa criterion of 0.7, this study as well as that of Gawel and Godden suggests that less than 30% of expert wine judges studied are, in fact, “expert.”

Consistent with these findings, wine guides are similarly unreliable. In fact, though they’re regarded as important for consumer purchasing decisions and brand reputations, there doesn’t seem to be anything standard about them:

The results show considerable divergence between the qualitative and quantitative assessments by professional tasters in the Wine Enthusiast wine guide…. In fact, even when wines are grouped according to their characteristics, there are still discrepancies amongst experts. Therefore, it cannot be said that the guide follows a single, uniform set of criteria for its wine reviews.

Inconsistent, Sure. What Else?

An extreme example of oenophile claims failing to hold up is that dyeing white wine red confused expert wine tasters into describing them less like whites and more like reds. This is damning because red wines have tannins in them that come from the grape skins during fermentation. These are supposed to provide a different mouthfeel, but the lead author of the paper says that, even though anybody should be able to detect that feature, “About 2 to 3% of people detect the white wine flavor.”

But it’s not like there’s nothing to the hype, there’s just not much. In favor of there being something, consider Robert Parker. He is perhaps the most well-known wine critic alive today, and his opinions have sizable impacts on the price of Bordeaux. These opinions are also not random: Bordeaux prices are somewhat predictable from the weather! In fact, those simple regressions do just as well as Parker’s system. (Where have we seen this before?)

There’s also evidence that experts are better at recognizing and organizing wine-relevant aromas, and at describing them consistently. Tasters are also able to classify grapes and countries of origin at better than chance rates. In that example, tasters got grape varieties right in 47% of cases, and 37% of their country-of-origin calls were right too. With the number of possible options, that’s quite good, at least in a vacuum. This is both fortunate and unfortunate, though, because that accuracy stems from familiarity and training into a culture. That is, as people train at wine tasting, they become somewhat better guessers, but their preferences also shift towards snobbery, towards what the field values: older, more expensive wine with certain characteristics!

What Makes a Good Wine?

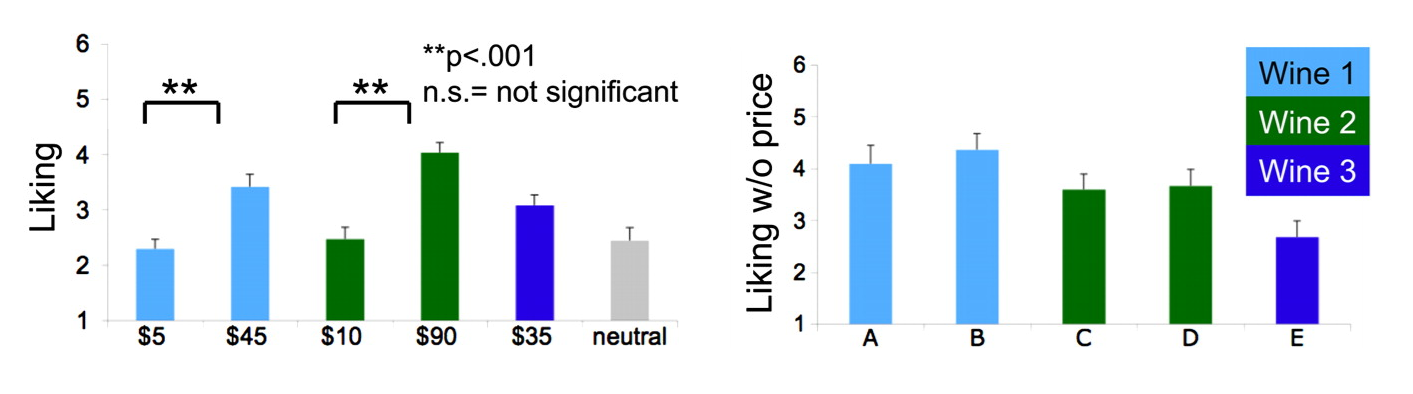

Unfortunately, regular people’s judgments of wines are readily influenced.

Including price information about wines in a tasting, for example, leads to disparities in evaluations (left). Masking price information (right) returns people back to their senses so they maintain that they “like” the same wine consistently when it’s served to them. This effect is strong enough to modify the rank-order of wine judgments to such a degree that they place wines they like less—in the absence of price information—ahead of wines they would actually like more!

But price does not actually seem to be distinguishable without training. When almost 600 people were asked to blind comment on red and white wines priced between £3.49 to £29.99 per bottle, they classified ones costing £5 and less differently from the ones costing £10 and more about as well as you’d expect from a coin flip. More to the point, people do not tend to rate higher-priced wines as more enjoyable when they don’t know the prices. In fact, for non-experts, the correlation between price and enjoyment is slightly negative, and only for individuals with training does it become positive.

Expertise in the world of wine is wildly overstated. Wine-related institutions are less reliable, more error-prone, and far less useful for consumers than they make themselves out to be. The prejudices of oenophiles don’t have a basis in what makes a wine desirable to normal people, and they don’t even seem to hold up when wine experts evaluate them. Because of facts like these, what makes a good wine isn’t set in stone; nevertheless, it’s obvious what makes a good wine: personal preference!

The best wine is the one you like—period.

Throughout this piece, I refer to sommeliers, tasters, experts, judges, and so on using these different terms, but I mean practically the same thing in most cases and where I literally mean something different, it should be clear from surrounding context or nearby links.

A reference to this controversy appeared in The Simpsons S1E11, The Crepes of Wrath.

In the case of certification cheating scandals, I believe that view is strongly supported.

To convince myself of this, I got different bottles of ‘the same’ wine and had people assess if they could detect differences. We’re not wine experts, but some of us have fine sniffers, and we couldn’t detect meaningful differences.

This means that what happens in other contests doesn’t affect other contests: no memory, no reputational boosts or halo effects from prior golds (blocked by blinding). It means that bottles do not carry over advantages across contests, so each judging is a fresh roll at the ‘dice’ with the same odds. This also means that judges and contests aren’t linked in other, hidden ways that make some bottles win together more often.

Stated in that last way, it’s hard to believe in independence, because judges do maintain their palate, they use the same or similar rubrics, and because contests often involve a discussion phase, judges might influence one another due to these common biases. But we should not believe in independence, it’s just used for illustrative purposes.

Because we’ve set the reliability, a gold becomes informative: conditioning on a gold, the posterior for a bottle’s pᵢ shifts way up, making repeats more likely. Given a bottle won in one contest, the chance it wins at least once in the other 13 is

Among 1,000 winners, you’d expect about 946 to also win elsewhere and only 54 to be unique.

As a final note, the model is overdispersed. The variance of golds in a contest across 4,000 bottles is huge, with an SD of 795, so given a mean of 346, seeing 1,000 win just once is only a +0.82 sigma event. The other parameters are what make the observed values so incredibly unlikely under any reasonable degree of reliability (as explained above).

To play around with this, here’s some code:

indep_fit <- function(overall = 0.25, T = 14, N = 4000) {

p <- 1 - (1 - overall)^(1 / T)

q_overlap <- 1 - (1 - p)^(T - 1)

list(

name = “independence”,

N = N, T = T, overall = overall,

p = p,

expected_winners_per_contest = N * p,

q_overlap = q_overlap,

unique_fraction = 1 - q_overlap,

pk = function(k) dbinom(k, size = T, prob = p))}

not_indep_fit <- function(overall = 0.25, T = 14, N = 4000, rho = 0.5) {

stopifnot(rho > 0 && rho < 1)

S <- 1 / rho - 1

target <- 1 - overall

f_root <- function(alpha) {

beta <- S - alpha

if (alpha <= 0 || beta <= 0) return(Inf)

val <- beta(beta + T, alpha) / beta(beta, alpha)

val - target}

alpha <- uniroot(f_root, c(1e-10, S - 1e-10))$root

beta <- S - alpha

pbar <- alpha / (alpha + beta)

q_overlap <- 1 - (beta(beta + (T - 1), alpha + 1) / beta(beta, alpha + 1))

pk <- function(k) {

choose(T, k) * beta(alpha + k, beta + T - k) / beta(alpha, beta)}

list(

name = sprintf(”beta-binomial (rho=%.3f)”, rho),

N = N, T = T, overall = overall, rho = rho,

alpha = alpha, beta = beta,

pbar = pbar,

expected_winners_per_contest = N * pbar,

q_overlap = q_overlap,

unique_fraction = 1 - q_overlap,

pk = pk)}For the independence model, just extract p, q_overlap, and expected_winners_per_contest. For the 50% reliability model, extract pbar, q_overlap, expected_winners_per_contest, alpha, and beta.

Another possibility is that wine contests fail to remove the effects of other wines on subsequent tastings in a given competition day. This is not really a possibility because it’s so obvious that of course there are credible (but imperfect!) attempts to account for it.

Tastings are blinded and independently scored (before being discussed), samples within flights are shuffled for each judge and across judges, the design is often a balanced incomplete block or Latin square, so no wine is always early or late in the flight. Small matched flights are sometimes used to group by style, alcohol, sweetness, or tannin, so intensity is comparable and the number of wines per flight is limited to reduce fatigue. Palates are also managed with spitting, timed breaks, water and neutral crackers, sometimes protein and fat (cheese!) for high-tanning reds, and temperature and glassware are standardized. Judges record notes and scores per wine without seeing prior wines’ scores to reduce anchoring, too.

Finalist wines are also often retasted in fresh orders to verify earlier impressions, but we’ll get to this.

New suggested name for your substack: “Cremieux Ruins Everything.” Like the old show but better, and with less snark.

I always said there was only two types of wine: good and bad