Most Trend Breaks Aren't Real

Shocking trends are more likely to be artefactual than signals of real things worth worrying about

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. I made the table for this beforehand. You can find my previous timed post here.

When a time-series suddenly jumps, plummets, or accelerates, the likeliest cause is a shift in how the phenomenon is measured—its definition, detection technology, reporting incentives, or data coverage—rather than a real-world change in the phenomenon itself. Whenever you see some hard-to-explain trend, it’s more likely to be artefactual than real.

I’ve compiled an unsystematic sampling of instances of this below. Suggest more and I’ll add them to the table!

I have no doubt that if you spend enough time looking at Twitter ‘data accounts’ in the abstract, you’ll find plenty of instances where the incidence of something changed for reasons that were not real, or which at least didn’t align with what many people were thinking. For example, Eric Kaufmann documented that a large portion of the rise in LGBT identities was due to a rise in identification as bisexual, without much evidence for a corresponding shift in non-heterosexual behavior. The rise was, it’s been argued, exaggerated by factors that promote identification without substance.

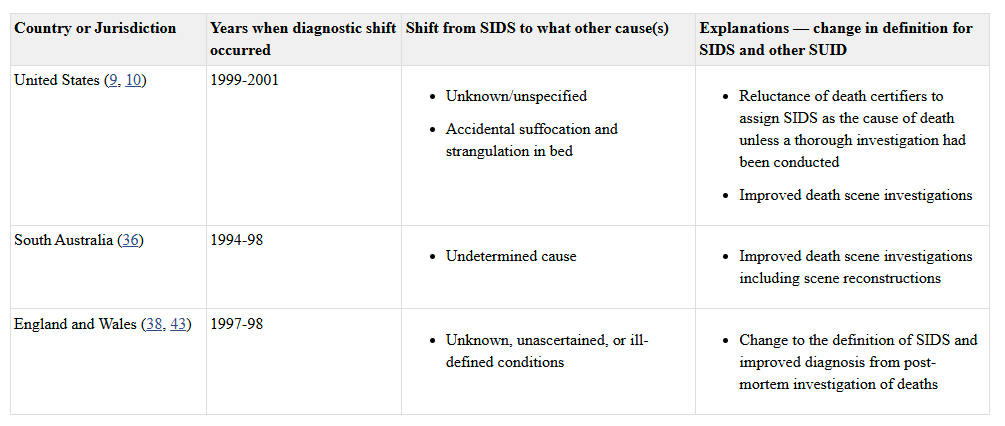

There are plenty of examples of false trends in medicine. One common example is “sepsis”. A stark rise in sepsis noticed in insurance claims was not supported when looking at the incidence recorded in electronic health records, deaths, or discharges to hospice. The purported ‘rise of sepsis’ was due to Medicare incentives to upcode patients and the adoption of other billing practices that raised the number of charts labeled “sepsis” without a parallel mortality rise. Similarly, did Lyme disease cases rise 70% in 2022 compared to 2017-19? No! Surveillance methods changed because they began allowing certain jurisdictions to start reporting based on laboratory test-based evidence alone, without the need for clinical confirmation. Or, more morbidly, did Sudden Infant Death cases rapidly decline? Yes, but some of this shift was due to diagnostic changes:

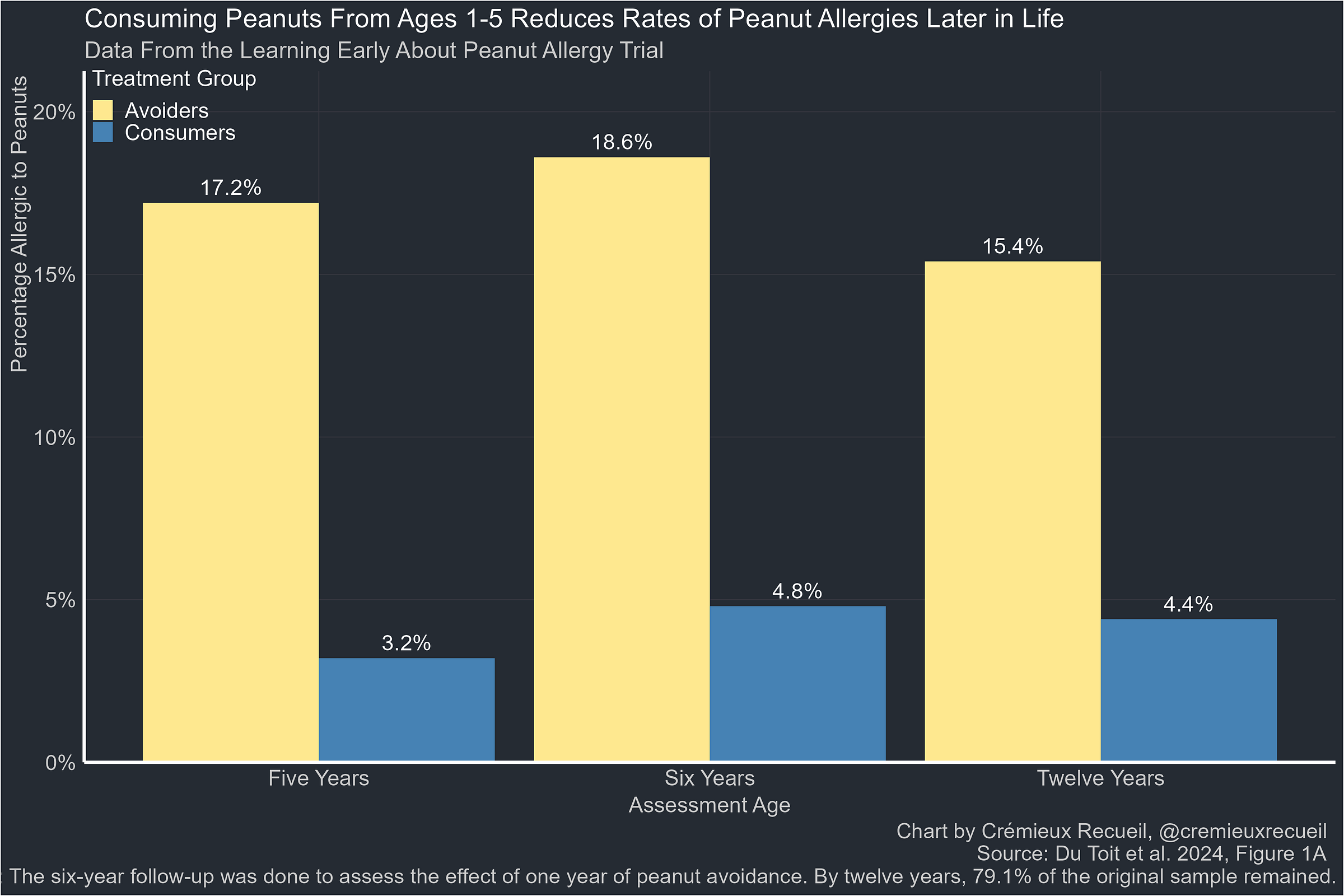

Often enough, rapid changes do have a real element. The SIDS example is one such case. But the trend was exaggerated for artefactual reasons. Sometimes trends are entirely real, but due to an abrupt societal response to bad information. For instance, in 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended parents delay the introduction of peanuts to their kids’ diets until age three. The LEAP study showed that this advice was exactly backwards, and waiting leads to a higher incidence of peanut allergy. By the time the AAP reversed course, the damage was done.

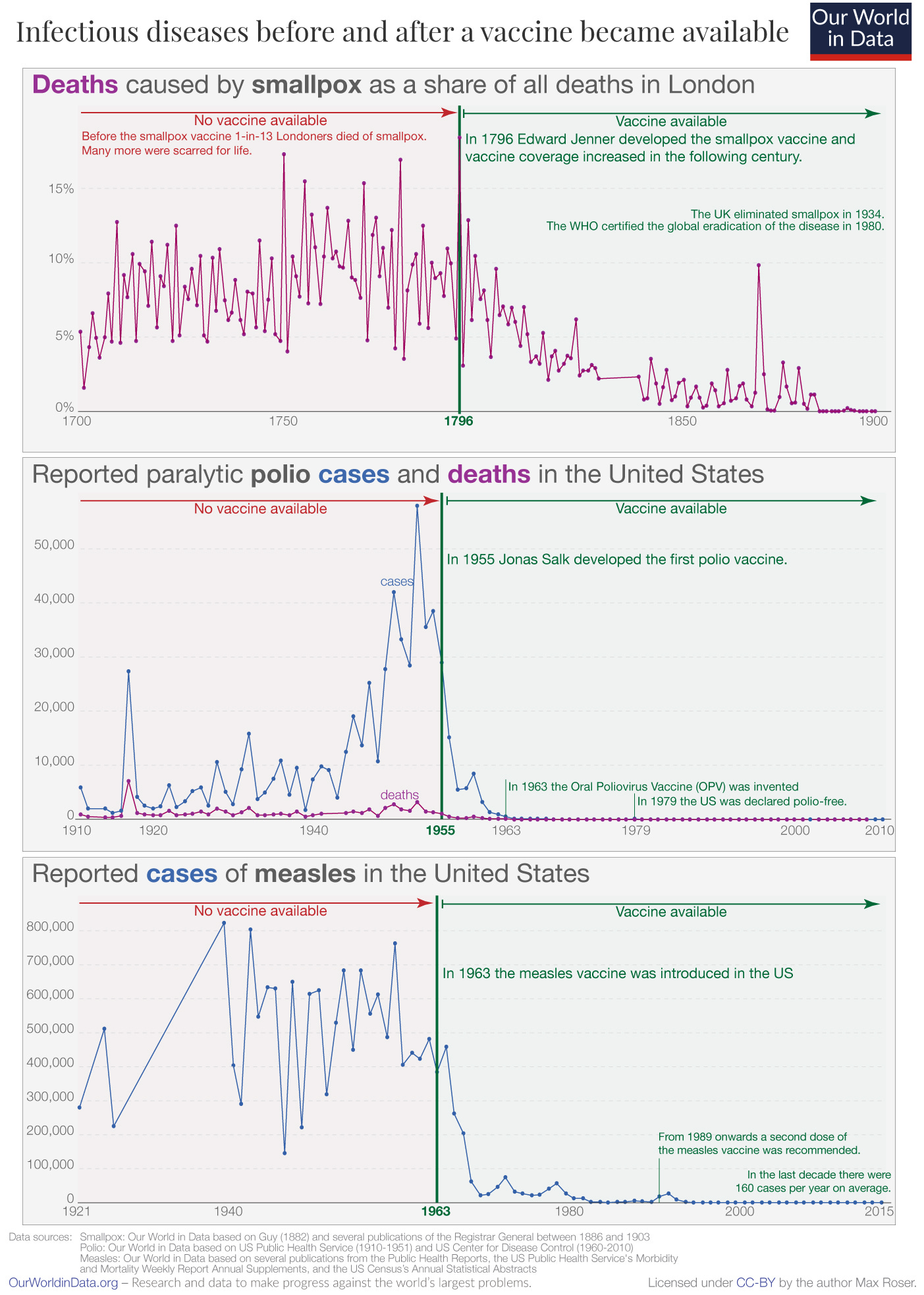

In the rarest of cases, trend-breaks are due to miracles. Economic liberalization and mass vaccination campaigns are among the few examples of this that come to mind:

Miraculous and abysmal trends are few and far between. The default assumption ought to be this: when something looks too good to be true, it is, and what we’re really seeing is an artefactual change, or perhaps as poor accounting of some data.1 When the world shocks us—as in the case of Cuba’s “exceptional” healthcare system—it is more likely because we’re being presented with something unreal than that we’re seeing something truly awe-inspiring.

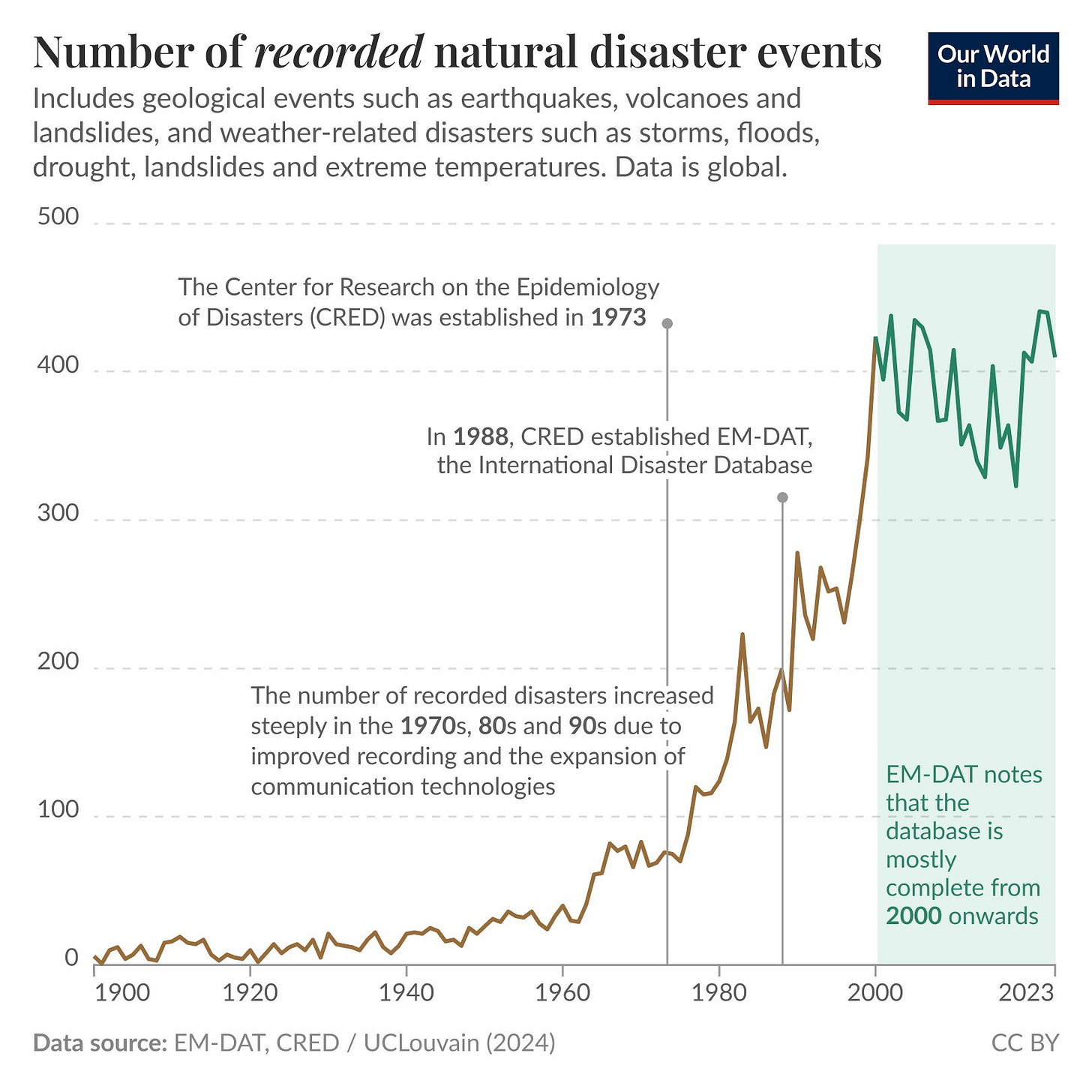

The thing that inspired this post was natural disasters. Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data documented that the frequently-touted four-to-five-fold increase in natural disaster numbers over the past half-century has more to do with the adoption of satellite monitoring, improved communications technology, the spread of the Internet, and intentional and recent efforts to catalogue disasters. To be sure, there may have been a real increase of late, but this data doesn’t provide unequivocal support for it, and indeed, as more disasters have been documented, they’ve tended to become less severe. Part of that hopeful trend might be down to an improved ability to respond to disasters, but a likelier candidate is better reporting.2

For example, some people like to use poor-quality data to exaggerate the increase in ultraprocessed food consumption, when high-quality data shows a more slight increase in consumption shares over time.

In case it is not clear, reporting can explain all or part of trends by improving and by getting worse. This instance is just one where the cause is clearly improvement.

Yes, when I see a supposed break in a trend, my first thought is:

1) Did the metric change?

2) Is there something the matter with the raw data?

Wow, so it's 98% virtue signalling everywhere, not just "genocides"...