Nutrition Beliefs Are Just-So Stories

But I really wish they weren't!

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here. I placed the advertisement before I started my writing timer.

Americans are fat. Is it because their diets are full of sugar? That would make sense because, after all, everyone knows sugar makes you fat.

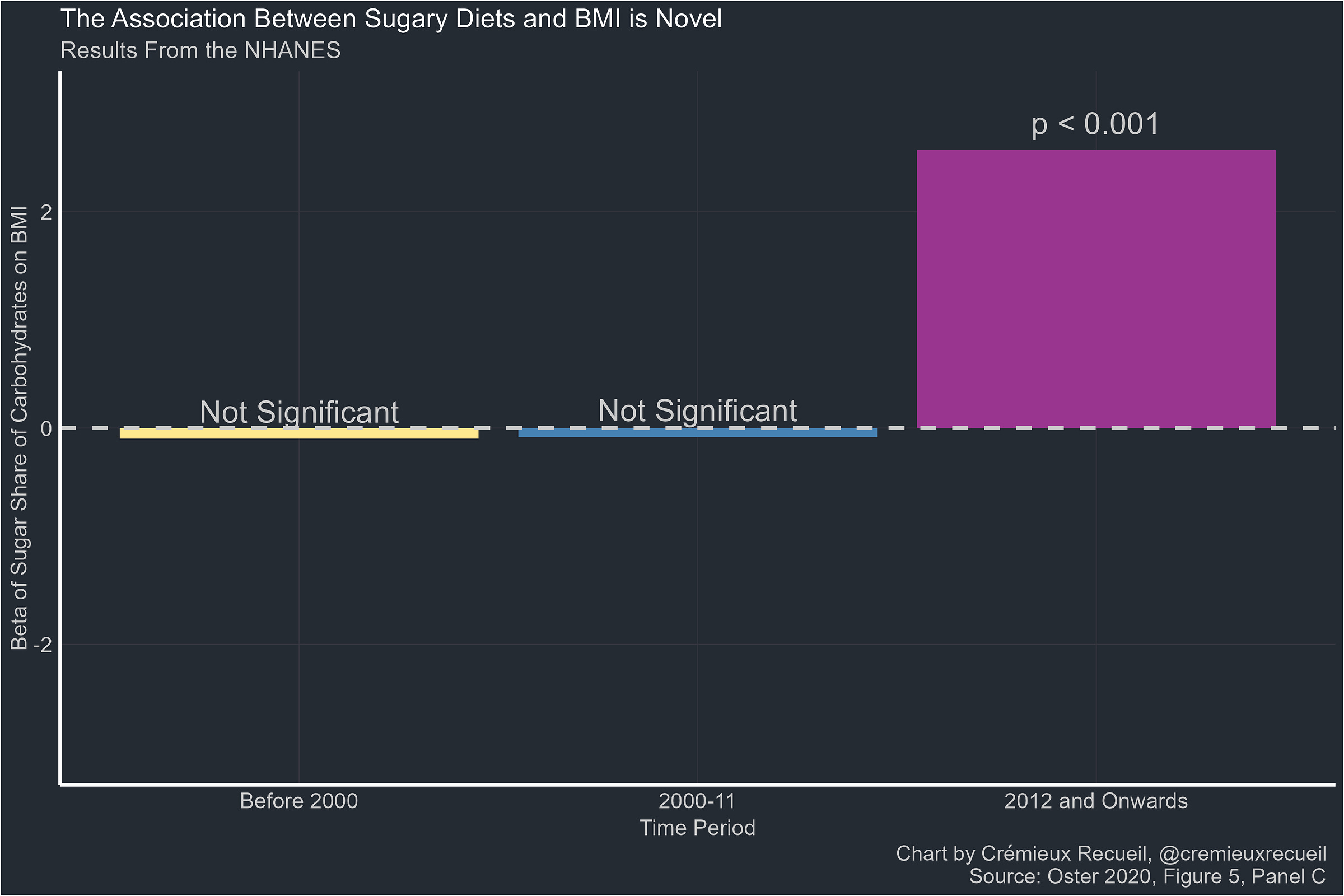

The harms of sugar have been the received wisdom ever since 2000, when U.S. dietary guidelines were updated to include explicit to encourage avoidance of foods with added sugars. After that guidance went out, people reduced the sugar share of dietary carbohydrates, but obesity didn’t seem to respond. If sugar is so critical, how do we explain that?

The explanation is selection, and selection is the great enemy of understanding in nutritional research. Consider some of the socioeconomic and wellness habit correlates of getting a higher share of your dietary carbohydrate from sugar. These things have changed over time:

People who obtained a higher share of their carbohydrates from sugar used to be more educated, higher-income, no less liable to exercise, and only slightly disposed towards smoking more. But after the news got out that sugar was not recommended, the associations drifted. In the period after Gary Taubes graced 60 Minutes and mainstream newspapers galore with the news of sugar’s harms, the associations kept becoming even more severe.

In other words, healthier people recognized sugar was bad—because the government and well-regarded authors started saying it was bad—and they turned away from it. But so what? The answer is that selection made sugar bad.

Having a more sugary diet was not related to being fat prior to the advent of the government’s advice or Taubes’ popularization of the concept that sugar is bad. And then, after healthy people stopped eating as much sugar, it became bad, at least cross-sectionally, but, because selection drove the change, probably not causally.1

This is a common pitfall for nutritional science to fall for. Selection in response to health news, beliefs, theories, myths, memes, and so on makes it difficult to evaluate the effects of different diets cross-sectionally. Certain people eat certain diets, and what we might assume is the effect of those diets could just be the effect of certain people wanting to eat in different ways, irrespective of the effects of diet, as with sugar.

A reversed example might make the issue of selection clearer. Consider the case of vitamin E supplementation. In 1993, two studies in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that supplementing with vitamin E could reduce the risk of heart disease. In 2004, a popular meta-analysis found that high doses of vitamin E were associated with increased rather than decreased mortality. In the NHANES and the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), people reported a massive uptick in vitamin E supplementation after its’ alleged health benefits became known, and they reported a reduction after its’ alleged harms were better appreciated.

During the time in which vitamin E supplementation was held in high regard, we see the same pattern we did with sugar: its use became confounded with class markers. Healthier people started supplementing vitamin E, but before and after the ‘healthful period’, the correlations dropped.

You can already guess what happened with the correlations with actual health. They were boosted between reports, but then things went back to normal.

The same story holds up with vitamin D and the Mediterranean diet, with breastfeeding, with vitamin C, with workplace wellness programs and so much more, in different datasets, with different stories, and across different years. What we have here is a robust effect of public perceptions on self-selection into certain types of supplementation and dieting:

Because healthy people want to be healthy, they adopt certain habits, making those habits appear healthier than they actually are.2

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

Further Problems

There are a lot of ways to fail at understanding nutrition. I showed the problem of selection above to make one of them clear, but there are many others.

Hastily Accepting Bad Evidence. So much of what people believe about nutrition is based on evidence that is hopelessly confounded or otherwise in error, and a lot of what people consider good evidence is only capable of misleading. For example, lots of people love the concept of Blue Zones, and believe in the life-extending powers of what they understand to be Blue Zone lifestyles. Fans want Blue Zones to be real, because their reality offers something good to the world: they’re felt to be a model for living a longer, healthier, and even a more harmonious life.

But then it turned out that Blue Zones were fake and they did not actually have any advice to offer the world: millions in book sales, a television series, speaking engagements, research papers, and nothing to show for it.

It Worked for Me! People frequently promote diets that aren’t special in any way, because “it worked for me”. Great! If something works for n = 1, that doesn’t provide an indication that it’ll work for anyone else, or even that it worked for the individual in question, barring some additional qualification like How did it work? Did you go off and on to test it? Are your criteria objective?

Don’t Forget Regression to the Mean. One of the most popular forms of self-delusion about diets that “work” for individuals comes when they convince themselves that a diet fixed some ailment that would’ve gone away regardless. Regression to the mean is the norm, rather than something exceptional, so if you’re struggling with an achy back, a runny nose, some bloating, or a weird lump and it “goes away” right after you decide to start a new diet, the most likely explanation isn’t cause-and-effect, it’s happenstance. Recommending others follow your derived advice is unlikely to net them any benefits, but you’re sure it worked, so why not offer away?

Misplaced Trust in Yourself. This is basically how I see every bit of common nutritional or exercise advice or ‘knowledge’: it’s almost all derived from being deluded. Practically all of it comes from hearsay, unsystematic self-experimentation, selective readings of literatures, extrapolating from confounded correlations and the weakest RCTs you’ve ever seen, etc. And there’s good reason for this: What people “know” is plagued by self-assuring hopefulness.

If you like vegetarianism for moral reasons, you’re likely to come to the conclusion that it’s also good for nutritional reasons; if you like the Mediterranean diet because tomatoes are your favorite food, then you’ll be proud to share those family recipes your Italian grandma used to make you; you want to have maximum testosterone, and you saw a study saying black licorice and strawberries lower it, so naturally you’ll refuse any opportunity to eat those foods; someone told you that replacing carbohydrates with fat would make you lose more weight even if you ate the same number of calories (thermic effects of food and whatnot)3, so now you’re a fat-maxer; you were told seed oils are mixed in sludgy vats, so, screw waiting for evidence, they’re obviously bad! (Right?) Regardless of the answers, you saw something that prompted you to make a choice, and now you’re going to justify it.

Belief in a Simple World. You heard that in Europe, the people are skinnier and they live longer. You take a trip to Britain, you see the skinny people, and you conclude that what you’ve heard is right and there’s something to learn from this little island. You study the lifestyles of the people there, their weekend activities, the number of steps they walk from their flat to Tesco in an average week, the food, the sleep, all of it. And you conclude… Britain is special, and America has something to learn from it.

But then it turns out, most of what you saw was because Britain is just poorer than America. To make matters worse, after we account for race, age, and America’s penchant for violence, Britain might even be in a worse position health-wise at the same levels of wealth. What, then, is there to learn? How to be healthier by living a poorer life?

But this sort of abject failure to reason carefully before making conclusions is de rigueur among policymakers, among book authors, among public personalities and influencers of all stripes, and out there in the wider world. People genuinely tend to think they’re just comparing like-to-like when they make statements like ‘Singapore spends much less than the U.S. despite having a higher GDP’. They tend to think that countries are different for the reasons they want them to be (‘Reverence for the elderly promotes Japanese lifespans.’//‘The diets in Sardinia are great for health!’), and in forming their beliefs, they lose track of their duty to do their due diligence to figure out factors that we can confirm differentiate countries in a meaningful way, like wealth, age, race, immigration status, rates of gun ownership, and so on.

The Stuck Influencer and Influencee Problems. A lot of nutrition and exercise knowledge people have comes from influencers. Sometimes they run YouTube channels, sometimes they spam TikTok or put out Instagram Reels, and many of them even write books. Only a very small portion of them have something important to say, and of those few, it’s still extremely unlikely that they’re consistently right about multiple subjects or all the ins-and-outs of the ideas they promote.

A major problem with influencers is that so many of them develop a shtick. They promoted some unique diet and they became associated with it and apparently knowledgeable about it. But these things often fail, and they don’t want to go and admit they’re wrong. There are numerous examples here, from the advice in The China Study to the dietary recommendations of Seventh Day Adventists to Taubes on sugar to vitamin D as near-panacea—it’s all bunk, but the promoters have to spend the rest of their years ignoring the counterevidence.

Even Blue Zones—now known to be centers of fraud rather than longevity—are still being actively promoted. They will undoubtedly persist as their creator intended them to for many years after their thorough discrediting, and they’ll persist as the people who bought in desire them to just as easily.

Get Scientific. We now know that sugar wasn’t promoting obesity until people started believing it was bad, so if someone tells you how you need to put down the Mexican Coke, try asking “Why?” and following up by asking “How do you know?” To avoid promoting nonsense, it’s a good epistemic practice when you notice something unusual to think less about ‘How?’ and more about ‘If’.

When someone is telling you something, ask them if what they’re saying is true and how they know it, rather than asking them to explain how what they’re saying is right. People have a preternatural ability to confabulate self-justifications and a capacity for self-deception that lets them turn weak evidence into strong beliefs, so scrutinize harder, and make sure that there’s good reason to believe something needs to be explained long before you try explaining it or letting other people explain it to you. If you don’t do this, then you’re liable to fall into believing a story that’s “just-so”—it makes internal sense, it’s appealing, and it might even be helpful, but it’s not right.

And if you’re a policymaker just trying to understand the world of nutrition and exercise, for the love of god, consult well-qualified, neutral scientists for help before you turn just-so stories into rules and recommendations that govern peoples’ lives.

P.S. I realize the title is hyperbolic. I wanted it to fit on one line, so I took out the key qualifier “mostly”.

Don’t misread this. I am not saying that sugar is good, or even that it’s neutral, what I am saying is that nutrition-related relationships can become and usually are impacted by selection in ways that complicate inference.

In trials with ad libitum eating, when people increase sugar intake, they gain weight, and when they reduce intake, they lose weight. Perhaps sugar leads people to overeat more readily, or maybe people advised to substitute sugar into their diets just eat more, and those advised to substitute it out do better portion control in the other direction. There doesn’t seem to be a sugar overeating effect based on studies featuring isocaloric exchange of sugar for other forms of carbohydrate. Or in other words, people who eat more sugar while reducing the consumption of other forms of carbohydrate in lock-step don’t uniquely hold onto weight, nor do they elect to eat other forms of non-carbohydrate food at greater rates.

Sugar as a ‘big bad’ of nutrition—as with any other such foodstuff characterized similarly—is a view that’s hard to seriously support.

This is not to say that the advice people adopt is necessarily bad or that the resulting selection makes cross-sectional inferences useless. As an example, the parents most willing to adopt the U.K. government’s advice regarding SIDS were healthier, more educated parents. This makes SIDS deaths more confounded, but the reason is that the intervention suggested by the British government was a good one, and less educated people with worse health habits ignored good advice, making them more disproportionate victims of SIDS deaths.

If I had to guess, in nutrition, nulls are more likely because so much popular advice that can be given doesn’t matter, whereas in basic childrearing, advice will tend to matter more because babies are genuinely fragile in ways that aren’t obvious to many parents, and especially not if they’re new parents.

Cross-sectional harms can also help with identifying excess burdens for different demographics, even if there’s confounding, as with SIDS, where the higher burden for the less educated could help with targeting education drives.

It's interesting how some diet advice sticks around longer than others. Your older contemporary Jean Brillat-Savarin wrote in Physiologie du goût (1825) that a primary cause of obesity, aside from variance in people's constitutions and lack of exercise, was eating way too much starchy food. He sounds like he's advocating the Atkins diet sometimes ("Avoid everything starchy in whatever form it appears. You still have the roasts, salads, and herbaceous vegetables."). He also notes the problem of eating when we aren't actually hungry.

Sugar and other carbs drive food cravings in "most" people.

Those cravings result in over eating. Which is why you gain weight.

That's why low carb. And keto work for so many people. They reduce cravings which means you eat less junk food which means less total calories which means you lose weight.

Also please note the word "most" studies have shown that people are different. There is no one perfect diet for everyone