People Listen to Public Health Authorities

Good news: people care about studies and guidelines and they want to follow rules! Bad news: that.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

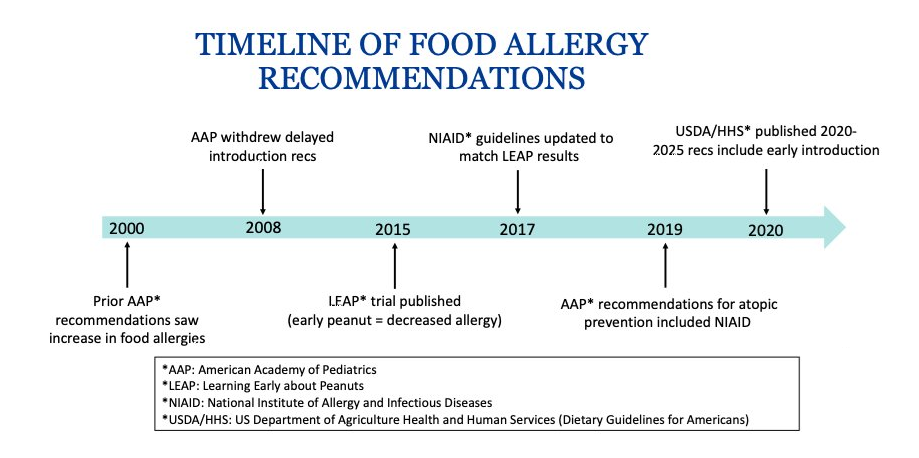

The prevalence of peanut allergy increased from 0.4% in 1997 to 1.4% in 2008 to about 2% in 2015-16. The increase happened because of bad advice. Specifically, in 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a recommendation that millions of parents immediately complied with. Their advice was to avoid exposing children to peanuts until they’re three years old.

The AAP made their recommendation on the basis of a few scant pieces of evidence, the opinions of a handful of experts, and the precautionary principle. Basically:

Some cohort studies showed that introducing kids to peanuts earlier was associated with more eczema, so they thought delayed introduction could prevent atopy (the tendency to show an exaggerated immune response to otherwise harmless things like peanuts).

Because peanut reactions can be life-threatening, they thought they should be maximally cautious and advise parents to have their kids avoid peanuts so that nobody dies.

The AAP’s in-house committee thought these things were compelling enough to advise parents to act.

There’s a logic to this that might be persuasive if this was everything we knew and the committee had strong, well-justified prior beliefs about allergy development. We do not live in that world. In the real world, the advice was hasty—ironic given the invocation of the precautionary principle—and numerous people in the field had good reasons for disagreeing about the scientific claims. Those disagreements were swept to the wayside and parents started following the AAP’s advice immediately, causing rates of peanut allergy to grow and grow and grow.

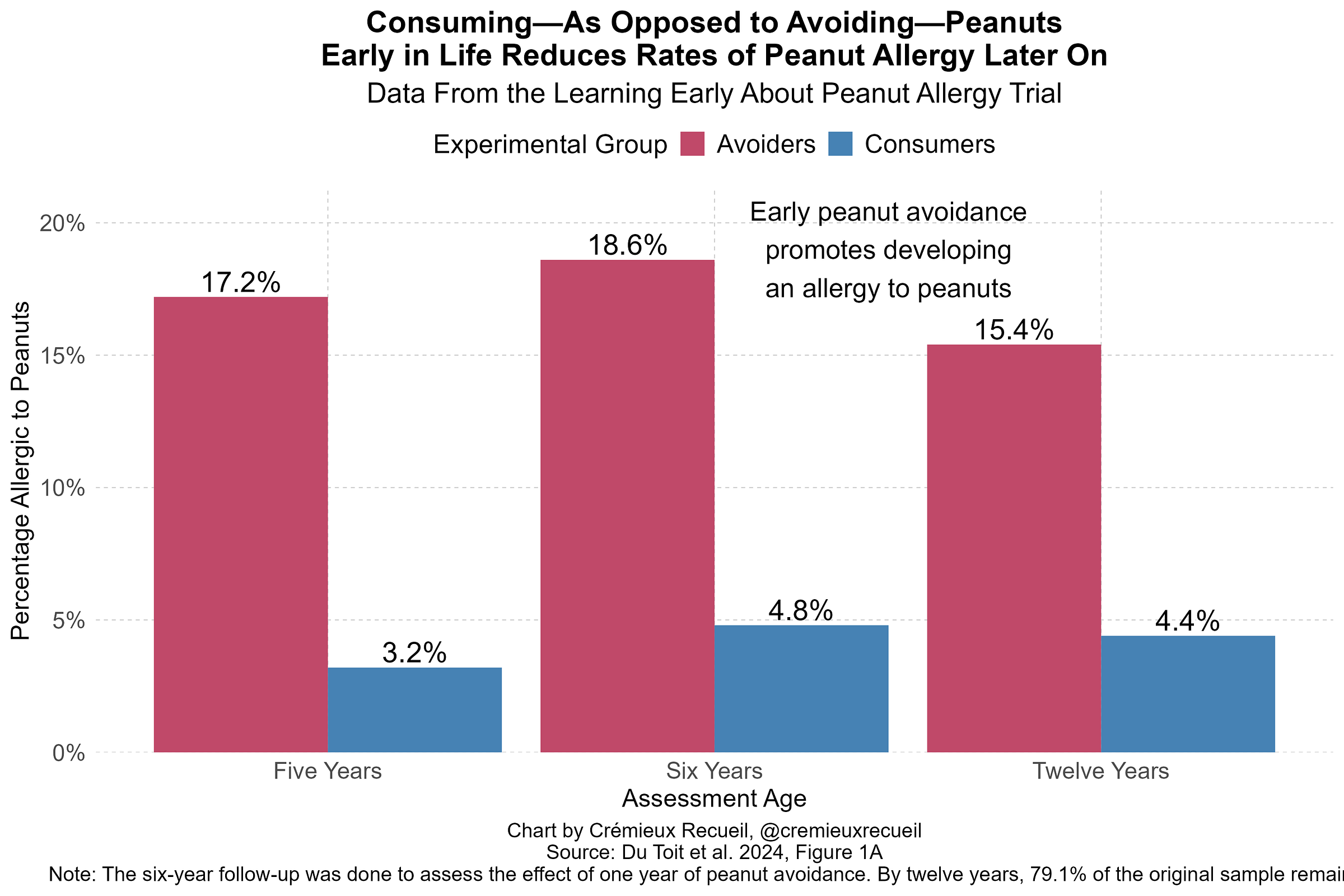

Luckily, the growing allergy problem inspired researchers to action and the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) trial kicked off. Participating families were told to either expose their young children to peanuts or to have them avoid peanuts entirely for a year. The result after five years of follow-up was clear: there was a much higher rate of peanut allergy among the kids whose parents were told to avoid the stuff. (This was not attributable to mortality.) At twelve years of follow-up, differences remained.

Two years before these results were released, the AAP abandoned their stance, citing a lack of benefit. Critics of the academy’s recommendation also noted the sharp rise in the number of children with peanut allergies and the fact that peanut consumption was convincingly observationally associated with a lower prevalence of peanut allergy. One of the more persuasive examples compared Jews in Britain to Jews in Israel—to control for genetic background—and found that British Jews had a rate of peanut allergy that was a staggering 10 times the Israeli rate. The difference seemed likely to be that Israelis consume a lot of peanuts, in the form of treats like Bamba. The early consumption of peanuts among Israelis is high, whereas it was practically nonexistent in Britain, which many researchers immediately took to mean that explained the difference. Given the results of the LEAP trial, it soon became clear they were correct.

But despite clear results and strong theoretical reasons to believe that early exposure was protective, the medical establishment was slow to update towards affirming the value of early exposure, so the rise of peanut allergy continued. But medical authorities did eventually update, and since then, the rate of peanut allergy has been on the decline.

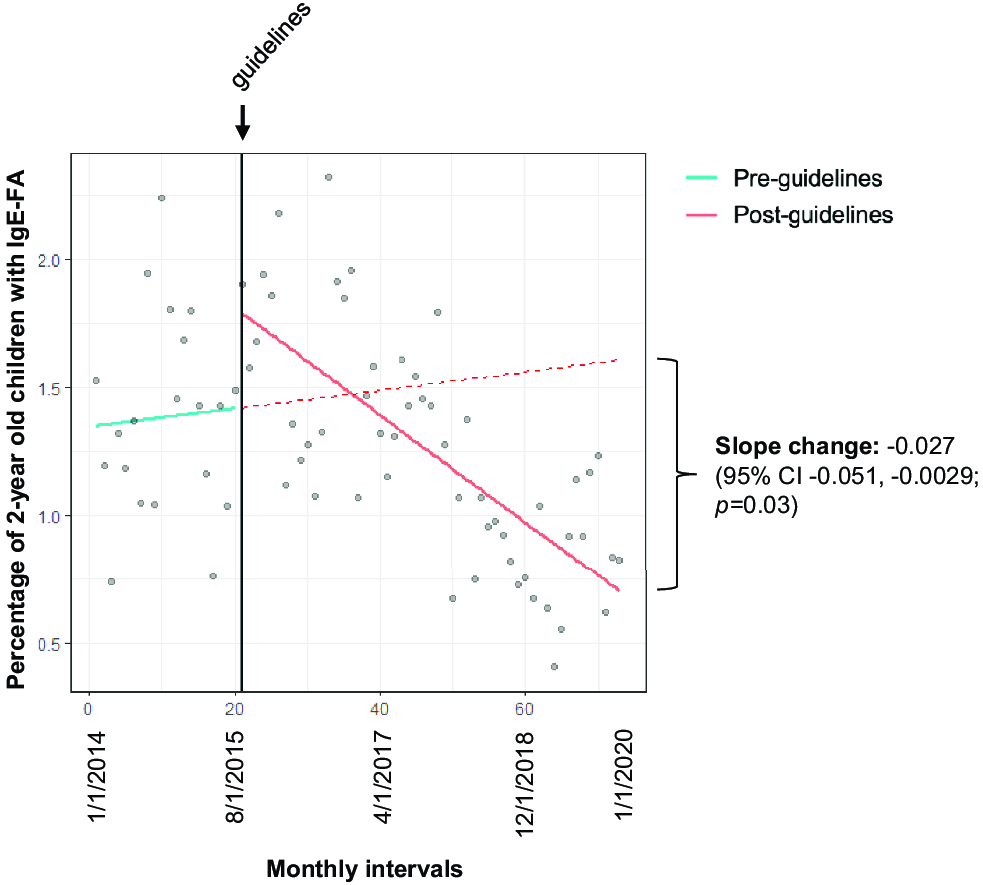

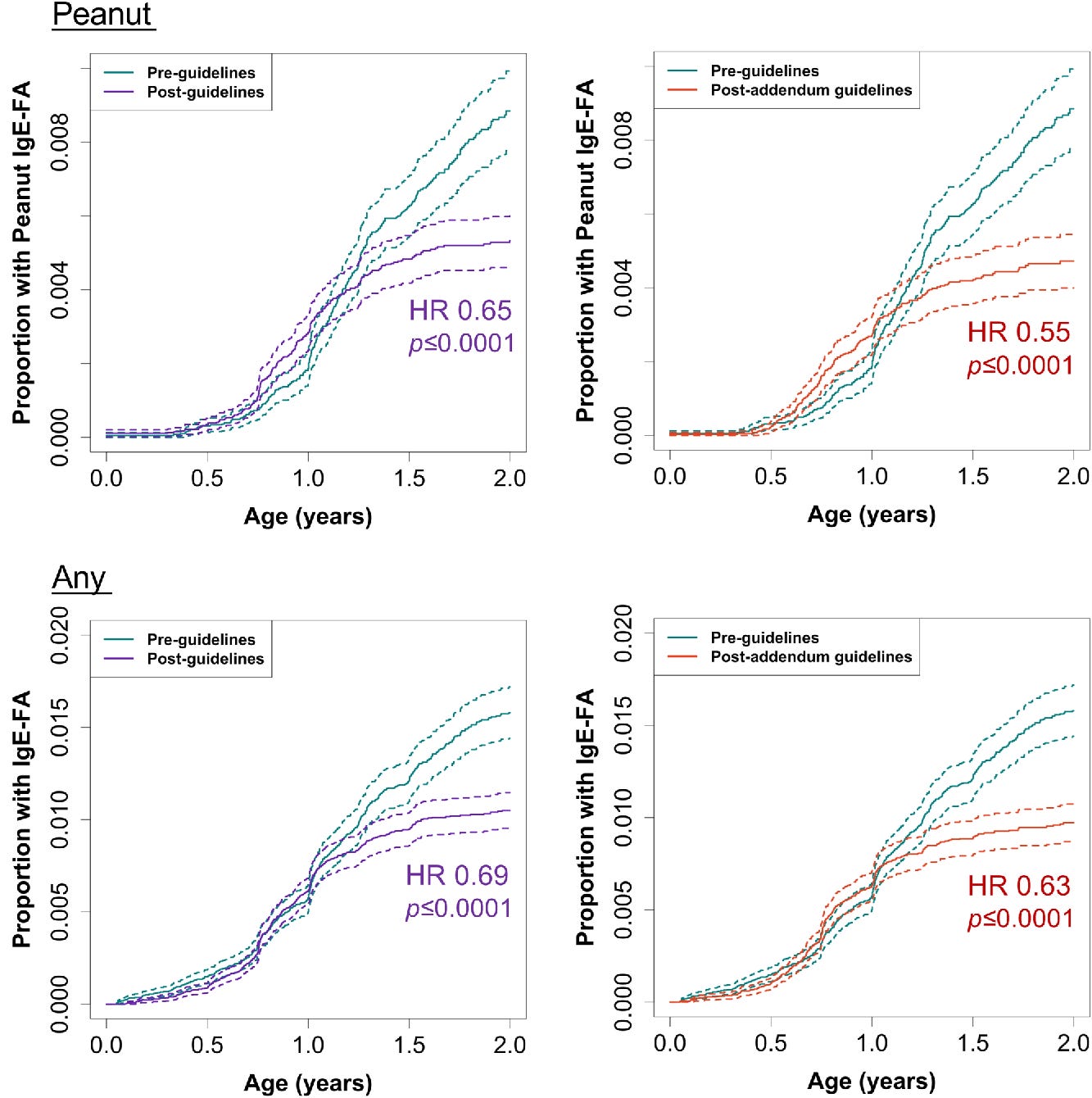

In 2015, multiple organizations updated their guidelines: introduce peanuts at 4-11 months to high-risk infants. In 2017, they added an addendum: introduce peanuts at 4-6 months to high-risk infants and at 6 months to moderate-risk infants. Then, in 2021, they updated again: introduce peanuts, eggs, and other foods at 4-6 months, and try to make sure infants have diverse diets. It took a moment, but parents apparently got the message and the portion of two-year-olds with documented peanut allergies began to fall:

Overnight, peanuts went from being the top allergen—a spot they’d consistently held for several years—to being #2, behind eggs. More convincingly, the risk of developing peanut allergies (or any allergy, for that matter) at different ages sharply fell for kids past about one year of age, which is when this should kick in.

Among children with at least a year of data, changes to the guidelines had managed to lower rates of peanut allergy by 43%. This happened practically overnight, making it readily apparent that, yes, parents do pay attention to and follow medical advice.

In one sense, this is heartening: we are finally turning a corner on peanut allergy! In another, it’s alarming. People can be convinced to follow correct advice, but they’ll also gladly follow advice that’s unfounded and incorrect if it seems to have authority behind it. We know this is definitely true for nutrition, where people will follow advice even when it likely does nothing but waste money.

Recent statements by the HHS have likely convinced pregnant mothers to avoid Tylenol, putting babies at risk from fevers. President Trump’s advice to split the MMR into separate M/M/R vaccinations spread out across more appointments will decrease total vaccination rates through the added difficulty of additional well visits and by scaring people away from vaccines more generally. A potentially forthcoming statement by the HHS about saturated fat will put Americans at risk of heart disease.

Announcements, recommendations, widely covered studies, and off-the-cuff advice might seem inconsequential, but they are not. They do impact people’s behavior in the real world. Getting public health right is a choice we can make, and if we get the public information part of it wrong, we might be sacrificing millions of people’s quality of life. The fact that we don’t have rapid and effective ways to communicate correct facts about nutrition alone could perhaps explain 20% of premature deaths.

I don’t have a solution to the very real, very impactful issue of health misinformation. I just know that I’m going to keep on calling it out when I see it. I hope you will too.

January 6, 2026 Update: Microdosing Peanuts

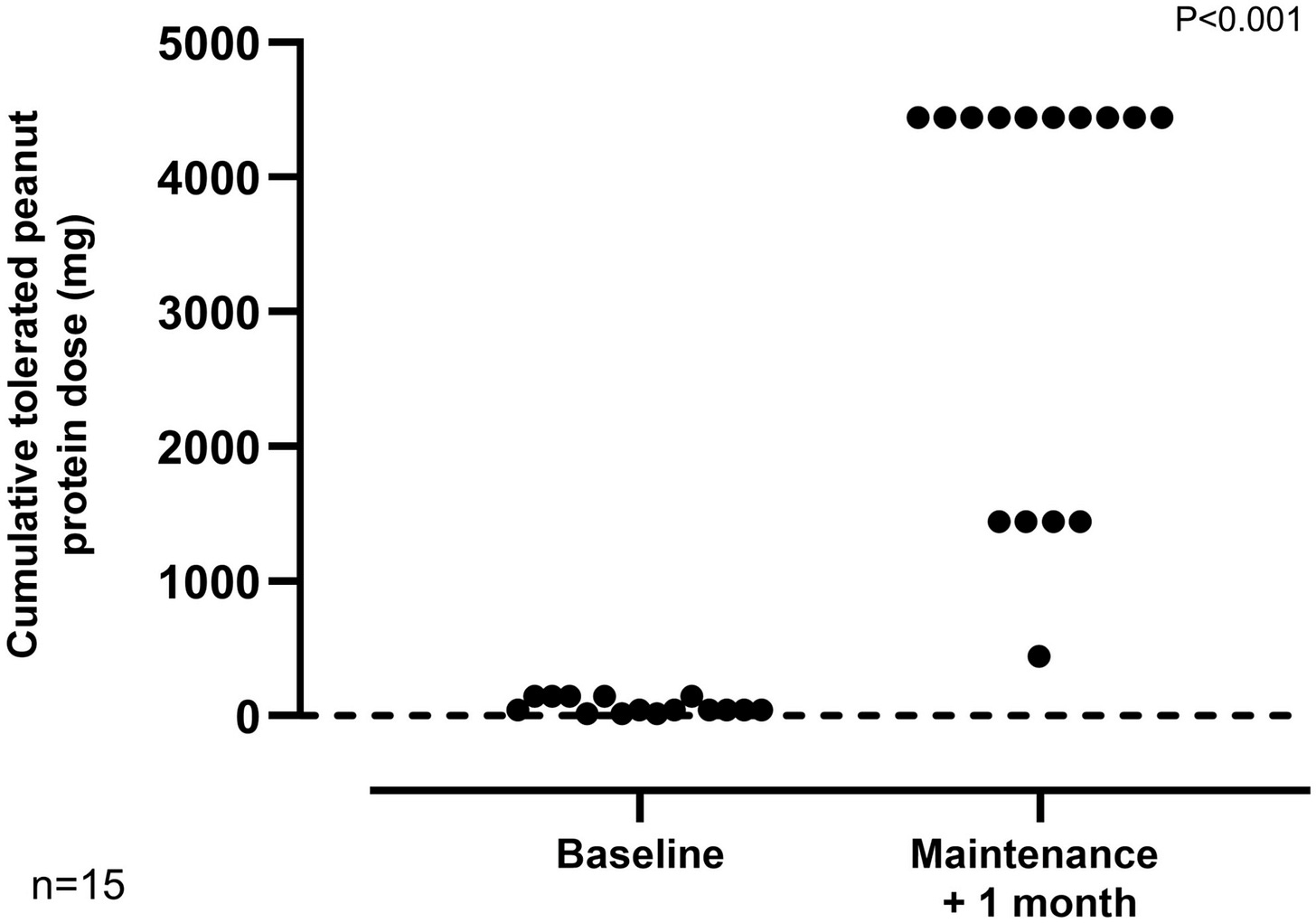

A small, new trial has provided some hope for peanut allergy suffering adults. The trial featured 21 participants titrating up from a peanut microdose each day until they reached a daily dose of 1,000 milligrams of peanut, after which they would maintain that dose.

There was some variability in the speed participants could titrate upwards, but most still reached the point where they could tolerate relatively large amounts of peanut. “The median tolerated dose increased from 30 mg (equivalent to approximately 1/8th of a peanut) to 3000 mg (12 peanuts) at the exit challenge, representing a 100-fold increase (p < 0.0001)” in tolerability, and a far cry from being subject to random, fatal allergic reaction.

This trial is hopeful. If it’s replicated and extended, it might represent a way to not just prevent future peanut allergy—as in the LEAP trial—but to fix existing peanut allergy. Perhaps public health authorities will eventually recommend this sort of therapy, and undo the damage they’ve visited unto millions of people.

I am reminded a bit of this by Scott Alexander https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/webmd-and-the-tragedy-of-legible

But it is also just depressing, authorities are making basic easily avoidable mistakes and medical authorities are clearly the smartest, most accountable and most competent "experts". Everyone in crime and education policy is far worse.

Thanks for the excellent article. We are in an age where a concerted effort to eschew modern medicine is all the rage. Ignorance is endemic, and many people have no interest in rational thought.