Pit Bulls Part I: Identification

Pit bull type dogs are readily identifiable

Pit bull proponents frequently argue themselves into the absurd position that pit bulls are a type of dog that can be straightforwardly identified for the purposes of advocacy, but which is unidentifiable for any sort of scientific analysis that makes it look bad.

What’s a Pit Bull?

Firstly, it’s spelled “pit bull”, not “pitbull”, and it refers to a type of dog rather than a breed. “Pitbull” as one word refers to a rapper.

The pit bull dog type is composed of members of several breeds, including the American Pit Bull Terrier (APBT), the American Staffordshire Terrier (AmStaff), and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier (SBT). These are the commonly agreed upon breeds that are definitely pit bulls. Sometimes additional breeds are included under the pit bull label, particularly when said breeds are derived from the most commonly recognized pit bull breeds.1

What people now call pit bull types descend from 19th-century “bull-and-terrier” crosses. The idea behind this cross was to blend the strength of the bulldog with the drive and agility terriers were known for. Prior to the passage of Britain’s Cruelty to Animals Act in 1835, the dogs were selected so they could be involved in lion-, bull-, and bear-baiting—fighting much larger animals in fighting pits, the origin of the “pit” name in “pit bull type”—but then this form of absurd bloodsport was banned and the animal fighting scene moved towards more discreet and cheaper dog-on-dog fighting.

Dogfighting was immensely popular, an overnight success that resulted in the mass proliferation of pit bull types and their mixes. The sport eventually led to the only two actual breeds of pit bull, the APBT/AmStaff and the SBT. The former is more popular in the U.S. and the latter is more popular in the U.K. and Australia, but both were bred to fight.

Early dog breed classification neglected the pit bull because the organizations behind them rightly rejected the barbarity of dogfighting and didn’t want to encourage it by recognizing breeds involved in it. Dogfighting fans responded by creating their own kennel clubs that would recognize the breed. The APBT was recognized by one of these clubs—the United Kennel Club—nine years after John P. Colby began to breed the most famous line of them in 1889.

The reasonable revulsion that people feel towards dogfighting is part of why the subject of classifying dogs as pit bulls has become so confusing. The confusion is, in some part, intentional. When mainstream kennel clubs came around to recognizing pit bulls, they asked for the breed to be recognized by a new name because of the stigma of dogfighting. Thus, the American pit bull terrier became the Staffordshire terrier, and later, the American Staffordshire terrier, but these dogs are still cross-registered across kennel clubs that use different names for the breed; anyone who’s serious knows they’re still the same thing.2

Physically, pit bull-type dogs are imposing, especially so given that they’re generally medium-sized. They run deep through the chest, strong in the shoulder, and tight in the loin, with a back that carries power rather than length. The head is broad and cleanly cut, their jaws are strong and their muzzles are firm; the pit bull neck is corded and set into a chest that looks as though it were built to take strain. Pit bull forelegs are straight and substantial, hindquarters muscled and driving. Their coats are close and plain, no frill. For a proper pit bull, movement should be quick and springy, not lumbering: they need to be a dog that can turn, drive, and recover balance without waste.

Behaviorally, pit bull type dogs tend to be keen, forward, and intensely willing. They’re marked by aggression, and more importantly by their gameness—the tendency to persist in aggressive states and to persevere while fighting. A pit bull will refuse to quit once they’re engaged. They are also remarkably easy to engage in aggression, often without any intent to enrage them.

Ohio v. Anderson described the pit bull’s behavior as such:3

Unlike dogs who bite or attack merely to protect a person or his property and then retreat once the danger has passed, pit bulls besiege their victims relentlessly, until severe injury or death results.

The case also noted that “there are certain physical characteristics which distinguish pit bulls from other dog breeds” and said that these physical characteristics were, as stated in Hearn v. Overland Park “a short, squatty body with developed chest, shoulders, and legs; a large, flat head; muscular neck and a protruding jaw.” Further:

While these physical descriptions are neither absolute nor all encompassing, the traits listed are common enough among pit bull dogs to constitute the physical representation of a dog "commonly known as a pit bull dog." As dogs commonly known as pit bulls possess these physical traits, and as these traits are readily identifiable, the vast majority of dog owners, i.e. owners of German shepherds, Siberian Huskies, cocker spaniels, and other breeds, will know… that they do not own a pit bull dog.

Pit bull advocates and apologists frequently disagree about the reality of the pit bull’s history, the breeds included under the label, that there are physical and behavioral distinctions between pit bulls and other dogs, and so on. All of their complaints ring hollow, as they’re based on some combination of intentional deception (e.g., attempting to confuse people with interchangeable breed names), ignorance (e.g., being evasive about the appearance and behaviors of pit bulls, which they were known to have been bred for), or belief in outright falsehood. There are numerous examples to fill each of these categories, but the last is perhaps the most fruitful to address.

One of the common defenses of the pit bull is the lie that they were bred to be vicious only to other dogs, and not to humans, via intentional and immediate culling of human-aggressive specimens. This would, apologists propose, lead to pit bulls that were indeed fit for combat with other animals, but wouldn’t hurt humans.

For one, this claim is absurd. There is no indication that the selective pressure required to elicit a change of this sort was ever present in any known breeding program for or in the general population of pit bull type dogs. The dogs were generally segregated from humans by breeders who would almost-certainly not present dogs with many opportunities to showcase human-specific aggression worth punishing. The argument that culling man-biters led to a lack of human aggression is the argument that culling based on a likely nearly-random event—notably displayed human aggression by dogs in a breeding program—was sufficient to systematically change the nature of aggression—which seems breed-general—among these dogs.4

For two, there are no records supporting this claim. It is simply proffered by pit bull apologists as a fact based on nothing, and then supported by citing other people making the same unsupported claim. The evidence base is similar to the evidence for pit bulls being “nanny dogs”—not-so-elaborate fiction.

For three, it is simply untrue, and we know it’s untrue because major dog fighters have been candid about what they were doing and how hesitant they are to throw out otherwise good dogs just because they bite people.

In Thirty Years with Fighting Dogs, we’re greeted to descriptions of several of the dogs that now find their spots in plenty of pit bull lines, and they are frequently clearly human-aggressive! For example, Rowdy “wanted to eat anyone that came near him but his owner and trainer, and even they could not get him weighed.” More prominently in the lineage of the American pit bull, the dogs provided by John P. Colby were obviously human-aggressive, as one of them killed his nephew and another broke out and mauled a little boy! Moreover, Colby’s son claimed that pit bulls were “unexcelled” as watchdogs, meaning that they were definitely not human-friendly, as they couldn’t be if they wanted to have the job! There’s a reason golden retrievers wouldn’t make good watchdogs!

There are actually ample reports of pit bulls killing and maiming people around the time of their initial registration and popularization in America. There is no reason to think aggression towards humans was ever absent or lesser compared to the dog’s other forms of aggression. There’s also only negative evidence for the idea of human-vicious pit bulls being culled after the breed became popular. Some pit bull owners seem to have noticed this, and have commented to the effect that many prominent studs and champion pit bulls were, indeed, vicious towards humans. One blogger conducted a decisively non-exhaustive search and found known human-aggressive pit bulls behind at least 1,265 puppies. It is utterly trivial to find more.5

So, what is a pit bull? It is a generally stout, strong dog marked by unrelenting gameness, bred without respect for human interaction, for the violence of pit fights. Pit bulls are easily visually recognizable, which is why we can be so confident that the nature they were bred for has resulted in their overrepresentation among vicious dogs.

Fact Number 1: Pit Bull Advocates Are Wrong

Despite the well-known origins, nature, and appearance of pit bull type dogs, their defenders often assert that pit bulls are not, in fact, able to be visually identified. At the same time, some run pit bull-only shelters, microchipping services, spay-and-neuter drives, adoption efforts, television programs and advertising campaigns, and provide training grants just for pit bulls, so they must be identifiable in some way, and when they say pit bull type dogs aren’t identifiable, they’re basically mocking us.

Pit bull advocacy pictures, videos, and other artwork, make the distinctiveness clear. Here’s a random example:

In truth, pit bull apologists only believe that pit bulls are regularly misidentified when it’s convenient—that is, when pit bulls hurt the reputation of their breed by harming another living thing or otherwise causing havoc in their communities. Even taking their position seriously, however, they are just dead wrong, and we know they are:

Pit bulls are readily visually identifiable.

Pit bull apologists like to cite a handful of studies to claim that pit bulls cannot be identified. One of them is Olson et al.’s study of shelter staff ability to identify pit bulls.6 Specifically, they like to cite this line:

Whereas DNA breed signatures identified only 25 dogs (21%) as pit bull-type, shelter staff collectively identified 62 (52%) dogs as pit bull-type.

However, the study has some major limitations. For one, only dogs that were safe to handle by shelter staff were included in the study. I expect higher pit bull ancestry to correlate with greater danger to staff and a stronger pit bull appearance, so to me, this militates against pit bulls being identifiable in the study's setting for artefactual reasons. That’s supposition, but it is reasonable supposition given the breed’s history, so it is among the issues that needs to be kept in mind.

Another issue was that the study considered a “pit bull type” as any dog with 12.5% or more of pit bull type ancestry. However, “American pit bull terrier and pit bull were not included in the 226 breed signatures.” If a dog was entirely APBT, it would likely have been classified as an AmStaff and treated as a pit bull by the authors, but this is by no means guaranteed, especially because the authors sought out mutts and not one of the pit bull type dogs used in the study was a purebred or even over 50% pit bull type,7 leaving it likely that ancestry would be misassigned fairly often. Related to that point, the authors provided examples of dog classifications, and one allegedly misclassified dog was called a boxer by two of four participants and an American Staffordshire by two others. The dog was a boxer, but it’s unclear who’s wrong here, since the boxer is a breed related to pit bulls.

The study authors also gathered data on the breeds that dogs were assigned at intake, where only 19 of the 120 dogs in the study were initially classified as pit bulls. This compares to 31 who were classified as pit bulls when it came time to assign breeds for the study, suggesting that shelter staff are deliberately mislabeling these dogs for identification to the public. This interpretation is bolstered by the findings from another, similar study, by Hoffman et al. In that study, 41% of shelter workers affected by breed-specific laws—laws that generally ban pit bulls and other aggressive breeds—said that they would intentionally mislabel dogs from restricted breeds, “presumably to increase the dog's adoption chances.”8

If you want to try your hand at classifying the dogs in this study, you can do so at my website, www.pitguesser.com. Keep in mind that you’ll be seeing 100 of the 120 dogs in the study, including 23 or 24 (depending on the definition of a pit bull) of the 25 pit bull type dogs the authors used, since that’s the data we have available. I’ll come back to this later.

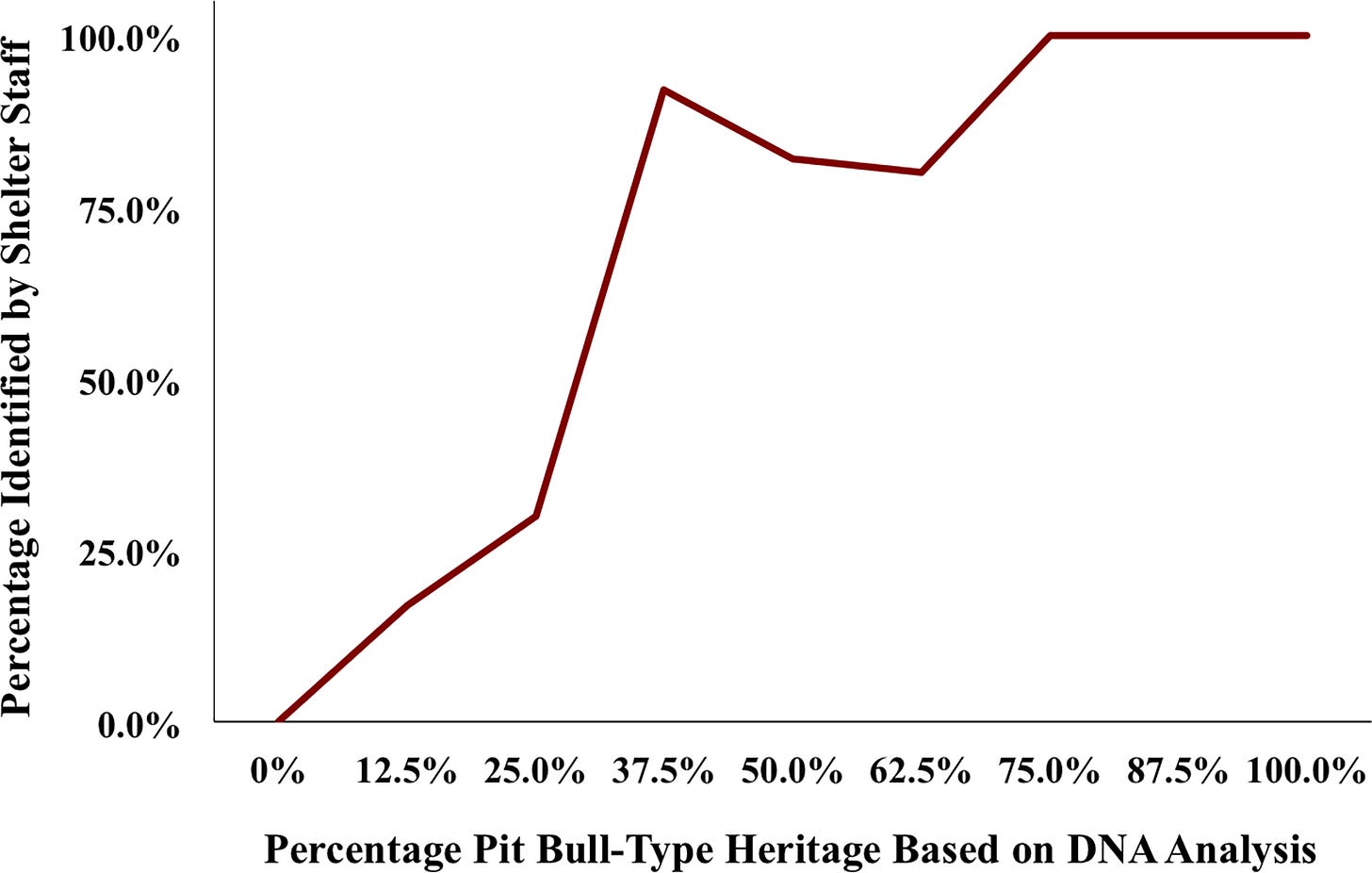

The other study that pit bull apologists commonly cite to make their point is Gunter, Barber and Wynne. These authors found that shelter breed assignments rarely matched DNA test results, with staff only being able to match one of the breeds for a given dog in 67.7% of cases, and only being able to match more than one of the breeds in 10.4% of cases. To some extent, that is unsurprising. When dogs are heavily mixed—as they so often are in shelters given how many of them are taken off the streets—it should be hard to identify all of the specific breeds since the appearances get blended.

Contrary to how pit bull apologists cite this study, it actually supports substantial identifiability for pit bull type dogs specifically. In fact, the authors showed that when a dog had 75% or more pit bull ancestry, it was correctly identified as a pit bull in 92% of cases! At the 80% threshold, every dog was correctly identified as a pit bull:

There certainly is something going on with pit bull appearance. Since the only other dogs that look like pit bulls are derived from the same stock and are also historically fighting dogs, this means clear identification of a dog as a pit bull is likely a good signal of substantial pit bull or pit bull-related ancestry! But I digress.9

Before moving on, I want to note a result from the ASPCA that I have not seen pit bull apologists mention. The ASPCA found that, of 91 shelter dogs visually classified as bullies—used synonymously with ‘pit bull’ here—, 96% were pit bull or pit bull mixes, defined by at least 25% pit bull ancestry. The purpose of this study was to increase adoptability, so the staff assigned to selecting the sample on the basis of their identification of the dogs as pit bulls or pit bull mixes were likely willing to play along and guess as well as they could. And, they did! They guessed extremely well and were clearly able to identify pit bull ancestry in dogs for recruitment into the study sample. Or, they got lucky because all the dogs available to them were pit bulls. While possible, I doubt that’s explanatory.

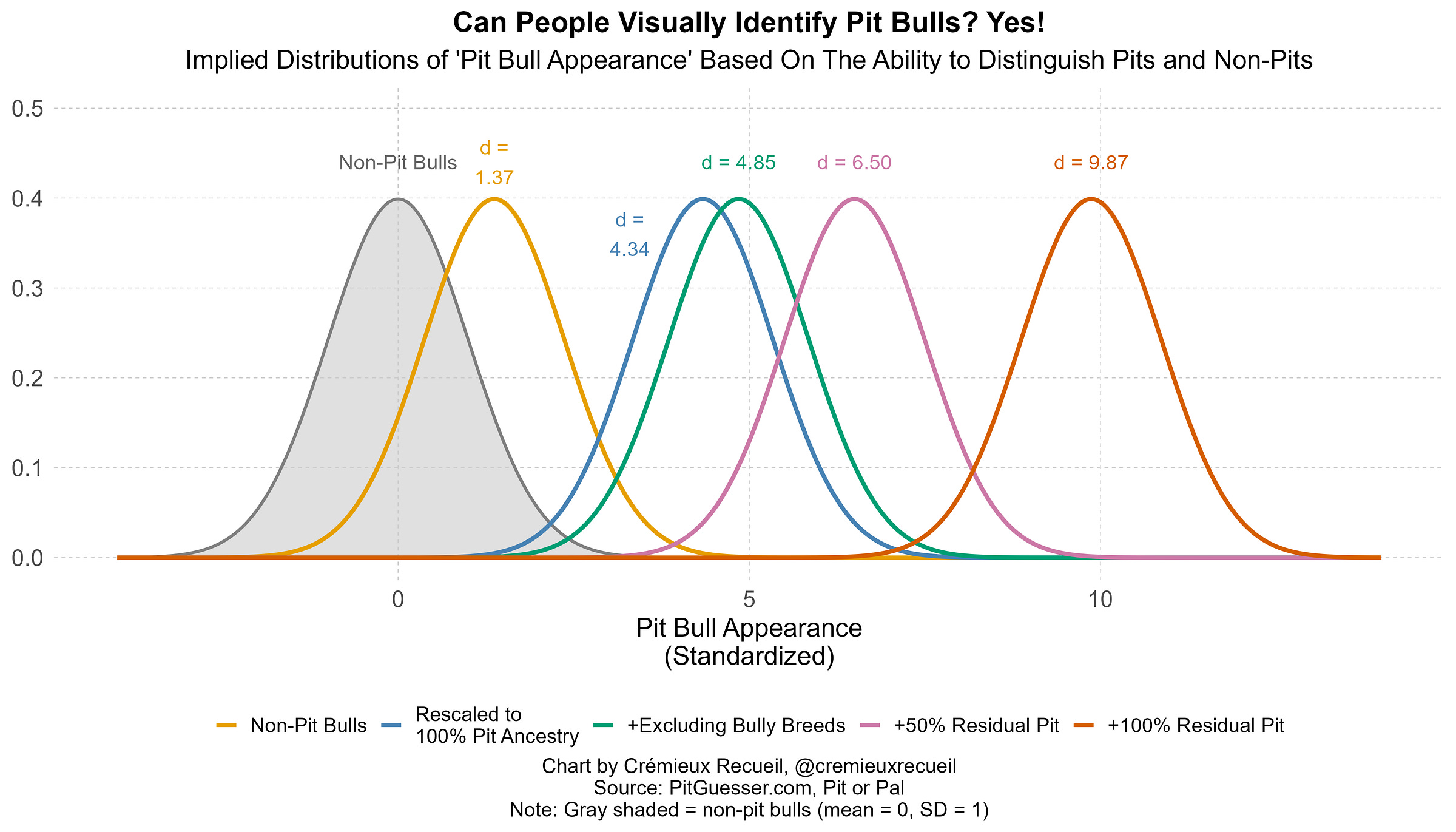

Now I’m going to return to the data generated by pitguesser.10 This data allows us to qualify and quantify how well pit bulls can be visually identified with a greater degree of clarity than we see in the rest of the literature. The images on the pitguesser website come from the Olson et al. authors, but the participants in that study got to actually meet a subset of the sample of dogs in-person, so their ability to ‘figure them out’ should’ve been greater than what we can get from pictures. Nevertheless, in the simplest game mode—Pit or Pal—, where two different dogs are compared and the user has to pick which is the pit bull, people achieved incredible accuracy.

After screening out repeaters, people who clicked too rapidly, people who completed fewer than twelve rounds, people who came from a pro-pit bull forum, and people who had previously seen the images in another game mode, we ended up with hundreds of thousands of players with valid responses in each game mode. People were correct at identifying which of two dogs was a pit bull in 83.4% of cases.11

The chance rate here is 50%, so, naïvely, the pit bull-non-pit bull difference in a sort of latent ‘pit appearance’ variable is given by

With P_c = 0.834, \Phi^{-1}(0.834)\approx (0.9701), so Cohen’s d = \sqrt{2}\times (0.9701) or \approx 1.37, which implies about 49% overlap between these distributions, with 91.5% of pit bulls having a more ‘pit bull-like’ appearance than the non-pit bulls and an 83.4% chance that a randomly-chosen pit bull will be higher on ‘pit appearance’ than a randomly-chosen non-pit bull.

This result is already substantial and it proves definitively that pit bulls can be visually identified, but it undersells the result: recall, all the pit bulls in this study were mixed breed dogs; notice that some near-pit bull breeds were included; and observe that we only have access to the top four breeds of each of these mixed dogs by ancestry and some of their ancestry totals do not sum to 100%. The gap in ‘pitness’ must therefore be even larger than the observed gap.

Let’s take this in order. Hypothetically, if pit bull appearance scales linearly with ancestry—something directionally supported by Gunter, Barber and Wynne, common sense, and in this data—, then we can rescale d to what it would be if the pit bull ancestry in the pit bull group was 100% per dog by dividing by the observed ancestry percentage of 31.6%. That brings us to a d of about 4.34, or just 3% overlap, meaning that essentially all pure pit bull type dogs look more like a pit bull than all non-pit bull type dogs.

So-called bully breeds—American bulldogs, boxers, English bulldogs, and bull terriers—were also included, and these are related to the pit bull and were also used in fighting, so can be easily confused for them.12 They constitute about 7.77% of the overall sample ancestry and 6.9% of the ancestry among those without pit bull ancestry. All the comparisons were random, and sometimes comparisons were easier, such as when persons were served a pit bull and a husky, but other times they were harder, like when a person was served a pit bull and a boxer. Without these, accuracy rises by three percentage points to 86.1%, leading to a 4.85 d gap, or just 1.5% overlap.

The last issue is one we can’t empirically address very thoroughly. Recall that ancestries don’t sum to 100% for all of the dogs. For the overall sample, we only see an average of 83.7% ancestry, with 83.2% among the pit bulls and 83.9% among the non-pit bulls. Some portion of this residual ancestry will very likely be pit bull, meaning that there’s going to be attenuation of accuracy because, in some cases, the non-pit bulls will be partially pit bull, drawing the groups closer together and perhaps causing classification errors.

One way to get at this is to look at when pit bulls were paired with purebreds. In those few cases, they were basically always correctly distinguished. Another way to deal with this is to model the effect of non-pit bulls being up to 16.1% pit bull and half-way between our existing estimate for 0% pit bull and that, 8.05%. In the 0% scenario, we have our 4.85 d. To rescale, we just take 8.05% out of 31.6% and then we take 16.1% out of 31.6%. With 8.05%, the d rises to 6.50, and with 16.1%, to 9.87. These values are so extreme that there is virtually no overlap in pit appearance between pit bulls and non-pit bulls. If we add in random measurement error to the DNA test and the responses, both values grow further, but we don’t even need to touch on this because the values we’re at are already incredible.13

People have no problem identifying pit bulls from non-pit bulls, even when the non-pit bulls are barely pit bulls. If we plot that, we see:

The other simple game mode is Pit or Not, and it permits conclusions that are much the same: people are able to identify pit bulls very reliably (>75% of the time if they did at least 25 rounds), and even more reliably if you cut out other bully breeds from the sample. Again, pit bulls are extremely identifiable. The third game mode—Guess Breed—, however, is quite complex, as it requires people to pick out specific breeds among mutts. People are good at distinguishing purebreds from mixed breed dogs, but they are really bad—as was found in the study this data came from!—at identifying specific breeds beyond the top breed a dog had, even with a constrained list of possible breeds.

The first design is simple and it shows definitively that pit bulls are identifiable from non-pit bulls. Whether this is possible is the key question that the literature fails to answer. The second design is also simple and it shows definitively that pit bulls are identifiable in general. The third design is complex and does not show that pit bulls cannot be reliably identified, because it is not designed to do that. It is designed to show how well people can identify specific breeds in samples that are largely composed of mutts, and people cannot do that very well, irrespective of their very clearly demonstrated ability to identify pit bulls. But the literature has concluded pit bulls cannot be identified on that errant basis. One can only wonder why.

Fact Number 2: Pit Bull Advocates Are Innumerate (Or Liars; Likely Both)

If pit bulls could not be readily visually identified, the implied effect on their representation among dogs that bite and dogs that cause fatalities is likely to be understated, not overstated.

Pit bull apologists argue that pit bulls can’t be visually identified despite all the media they put out depicting said pit bulls’ distinct breed appearance. They have a specific goal in mind: they want to claim that identified biters belong to some other breed.

To be fair to this perspective, the idea that bad dogs might be misidentified as pit bulls because there’s a stereotype that pit bulls are bad dogs makes at least some sense. But it’s incorrect because pit bulls are so visually distinct that the stigma against them is not because of misidentification, but because we can see that they’re bad dogs, unless all observers including owners are horrendously biased. Exaggeration is a possibility, but pit bull overrepresentation in violence is directionally clearly real.

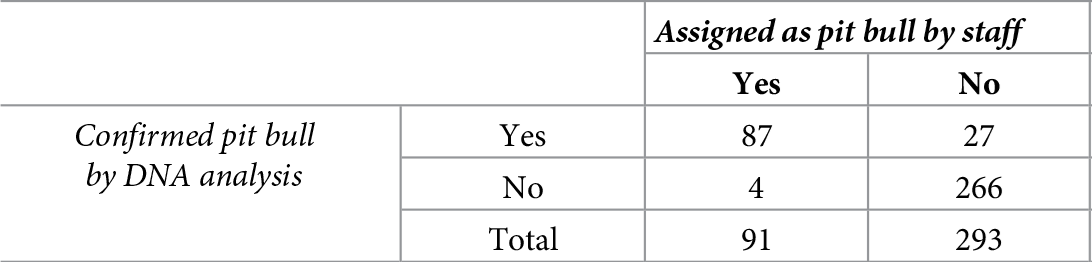

Let’s look back at the Gunter, Barber and Wynne study from earlier. If we look at their confusion matrix, we notice that there were 27 false-negatives, where shelter staff failed to identify pit bulls, and 4 false-positives, where shelter staff identified non-pit bulls as pit bulls. Of the 27 false-negatives, “20 (74.1%) were only one-quarter pit bull-type.” Furthermore, they were generally classified as mixed dogs. The false-positives were “either Boxer or Rottweiler mixes.” See Footnote 12.

The shelter staff were evidently quite good at identifying pit bulls, and their errors were likely explicable through some combination of poor reference panel quality, the common and reasonable practice of classifying bully breeds as pit bulls, and other ancestry predominating in the case of pit bull type dogs that only had a minority share of pit bull ancestry. But let’s just assume these errors were naïve to be generous to pit bull apologists.

First, notice that almost no dogs were wrongly classified as pit bulls. This alone militates strongly against the argument that other dogs could be getting classified as pit bulls when they act violently. The same pattern emerges in the pitguesser Pit or Not? data, and it becomes stronger when bully breeds are cut out, perhaps for the same reasons we would see if we treated the errors in Gunter, Barber and Wynne as benign (as we should).

So, second, what happens to the relative risk (RR) of biting a human, a dog, killing someone, or whatever else under such a scenario? The sensitivity in the study was 0.763 and the specificity was 0.985. The prevalence of true pit bull heritage dogs among all the dogs was 29.7%. With a PPV of 0.956 and a P(true pit | staff not pit) of 0.092, if non-pit bulls have baseline risk r_0 and true pits have r_1 = 10r_0, then the risk among staff-”pit” is about 9.6r_0 and the risk among staff-”not pit” is 1.829r_0. So, if the true RR is 10, the observed RR would be 9.604/1.829 = 5.251. Alternatively, we can invert this and use the same parameters with an observed RR of 10, to back out that the true RR would be 251.

Under error like we see in the Gunter, Barber and Wynne study, pit bull relative risk is clearly substantially deflated, perhaps to an unreasonably large degree. Reverse the sensitivity and specificity—Why?—and you still get evidence that the risk attributed to pit bulls will be significantly deflated by misidentification. With a true RR of 10, the observed RR would be 6.27, and with an observed RR of 10, the true RR would be 17.2. The exaggeration isn’t as large, but it’s still substantial, and now we’ve covered the most realistic error patterns, so there’s nothing plausible left for pit bull apologists to rely on to dismiss the elevated risk associated with pit bull type dogs.

For pit bull risk to be overestimated empirically, we need a different pattern of misclassification. The most plausible form of this is differential misclassification by outcome, such that among cases, non-pit bull dogs are more likely to be labeled pit bull type than among non-cases. In other words, you need to push cases into the pit-labeled bucket. Since we often have pictures of the dogs involved in assaults and fatalities, this isn’t a realistic risk unless identified dogs also wrongly appear to be pit bulls at excessive rates, which is something that’s implausible, as I’ve now shown.

Alternatively, pit bulls could be under-called in non-cases, meaning that among non-cases, true pit bulls are labeled something else. This could happen through licensing and adoption records softening labels, while bite reports remain the same. Similarly, pit bulls could be undercounted in the denominator in general, and overcounted in the numerator in general, for various other reasons. We know this isn’t a risk because we can just use the breed at registration for both counts, as is done in several countries with veterinarian or local authorities doing classification sometimes, and owners—who usually know their dog’s breed—doing it at others. Moreover, we can just use balanced samples, and even if this was a problem, it would have to be huge—generally too huge to be realistic!—for pit bull risk to be driven down to an RR of 1.

Pit bull risk can also be overestimated even if breed labeling is perfect if pit bull incidents are more likely to enter datasets. This is almost-certainly true, because pit bull gameness means their bites are more severe and more likely to lead to serious injury, which is likelier to be reported or otherwise noticed. But this is not a real problem for a few reasons. For bites that aren’t fatal, we care more about more severe bites, and we don’t care to punish ones that aren’t severe enough to enter the dataset. For bites that are fatal, we very likely capture all incidents, so this isn’t a real problem.

In Conclusion…

Firstly, pit bulls are readily visually identifiable. Statements otherwise are tantamount to gaslighting and you can disprove them to yourself by playing pitguesser. Secondly, if pit bulls are misidentified, the likeliest patterns of misidentification mean that the risk attributed to them has been underestimated, not overestimated.

Pit bull apologists can try to argue with these points, but they’ll never disprove them.

What’s Next?

This is the first in a series of four posts. It lays the ground work for the other pieces:

Part II: Pit Bulls Bite

Part III: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Pit Bull

Part IV: Policy Solutions to the Pit Bull Problem

Bonus Post: Wound Healing Advice Your Grandmother Didn’t Tell You

If you want to see these posts happen sooner, and especially if you’d like to see some action on the pit bull problem, consider subscribing. I appreciate the support!

By common derivation, the American Bully is a pit bull. This breed was explicitly developed from pit bull stock. The United Kennel Club (UKC) breed history describes the American Bully as “a natural extension of the American Pit Bull Terrier,” recognized as a distinct breed after a particular APBT “type” was developed. Per the UKC, the American Bully’s “appearance reflects a strong American Pit Bull Terrier foundation, blended with stock from other bull breeds.” The dog genetics company Embark likewise notes that the APBT was a foundational breed to develop the American Bully, which is a reason why the two often show very close genetic relationships.

The Bull Terrier and pit bull breeds share the 19th-century bull-and-terrier cross background, but Bull Terriers became their own standardized line with additional inputs and a different selection path. The American Kennel Club’s (AKC’s) Bull Terrier history explicitly frames the bull-and-terrier as a “starting point” for several breeds “including the dogs that today we call ‘pitbulls’,” and says Bull Terriers also descended from those crosses, then were molded into a distinct breed including odd influences like Dalmatians. Common derivation exists between the Bull Terrier and modern pit bulls at the bull-and-terrier level, but when Bull Terriers are called pit bulls today, it’s often an umbrella misuse due to people lumping ‘bully-looking’ dogs together, not because the Bull Terrier is part of the modern pit bull cluster in the same way the APBT/AmStaff/SBT are.

The American Bulldog is generally described as being descended from Old English Bulldogs and was historically bred as a farm utility dog. They’re also considered to have been bred as catch dogs for wild boar. That lineage is a bulldog working-dog lineage, not the classic bull-and-terrier to APBT/AmStaff/SBT line that’s been quite so behaviorally marred by a breeder focus on violent capabilities. You do see some American Bulldogs pulled into pit bull type in some popular, loose definitions because they’re blocky, muscular, and “bully” in appearance and because policies and media prefer broad buckets. You also occasionally see pit bulls mislabeled as American Bulldogs, when that is not what they are.

Boxers are usually not included under the pit bull type because of common derivation, and when they are included, it’s almost entirely due to visual misclassification due to inexperience. Boxers mostly come from a different branch of the bulldog family than pit bull type dogs. Their primary ancestry is the Bullenbeisser, which is a German hunting mastiff-type dog, then crossed with Old English bulldogs—themselves a predecessor to the other members of the pit bull type, which were bred for bull-baiting. The goals for the boxer were fighting, hunting, guarding, and later and to a lesser extent in working roles. But, crucially, there was no bull-and-terrier phase for boxers, which is the defining ancestral pathway for the APBT, AmStaff, and SBT.

The attempts to obscure the breed name of different pit bull type dogs are explicit and done in order to sow confusion.

Perhaps more importantly, dog fighters have historically been quick to attest that gameness can appear at a late age. In the above, Bronwen Dickey writes:

It is true that a lot of the Colby dogs are slow to ‘start’ or to ‘come on’, sometimes taking two to three years to fully mature. However, this is not uncommon with the breed as a whole. Also, when the Colby dogs did mature, they were well worth waiting on, being some of the gamest dogs the world has ever seen.

In Thirty Years with Fighting Dogs, George Armitage writes:

Some dogs go to fighting when they are still young pups. Others I have had do not show a desire to fight until 3 and even 4 years of age. When a pup gets to be 8 or 10 months old and shows a desire to want to fight, that is the time to begin to school him.

In The American Pit Bull Terrier, Joseph Colby writes:

One of the gamest dogs that ever crossed a pit, roamed the streets until he was three years old and until that time never had a fight. This dog fought in the hands of three different prominent dogmen and never lost a fight. He proved himself game and beat the best dogs in the country at that time.

Gameness must be bred in them and not put into them.

And, I’ll add, Colby also noted some pit bulls were chickens against stronger opponents, even if they were savage towards weaker ones:

I also know of a dog that won a contest lasting over one hour, apparently showing gameness. A few weeks later this same dog quit cold in seven minutes against a dog a few pounds heavier.

In Pit Bull Gazette, Richard Stratton writes:

Quite a flap was caused in my town when a local veterinarian advised a client that when he bought his Pit Bull pup, he had in effect acquired a loaded gun that could “go off” at any time-probably when he least expected it! Well, an amalgamation of Bull Terrier, Staf, Stafford, and Pit Bull devotees were all ready to tar and feather the good doctor and ride him out of town on a rail.

Our vet... did not want his client to be misled into letting his dog run loose. The problem is that the urge to fight comes to different Pit Bulls at different ages and when it does come, it can come so suddenly and without warning.

In The Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Phil Drabble writes:

But once he (or she, for bitches will fight) has tried fighting there is nothing they would rather do. And that is why I advise no one but a real enthusiast to embark upon the ownership of one of these dogs. The man who wants a dog for a household pet, but who expects it to run loose and look after itself will soon regret his choice. I have known them run loose in the streets and play with other dogs for two or three years. But sooner or later they either get hurt playing or mixed up in someone else's quarrel and suddenly realise what fun they have missed. From that time forth they need no second invitation and they fight to kill. Neither water nor any of the usual remedies will part them and I have seen a dog fighting a collie twice his size in a canal, where the owner of the collie had thrown them to part them. But the terrier could not loose and they both very nearly drowned before we could get them out. And owners who are not enthusiastic are often averse to getting sufficiently mixed up in the bother to choke their dog off, which is the only effective way.

These publications are all old, demonstrating a long-time awareness of this issue. Drabble’s writing, for example, was from 1948, and it featured mention of several of the prominent features of pit bulls today, including gameness, bloodlust, and the only effective remedy for their biting being to choke them. Others also noted high arousal, persistence, pain tolerance, and low threat signaling: observations clearly consistent with modern ones!

A dog can easily already have been bred or sold off before gameness developed or misbehavior took place. This makes the argument that their issues were detected and then acted on in breeding programs that much less persuasive.

All it took for pit bulls to be aggressive was for the trait to be bred in. After it was bred in—as it was in its predecessor, the Old English Bulldog—then only an intentional effort to breed it out or fantastic luck would make a dent, and merely not breeding for more aggression would almost-certainly allow the trait to persist for a very long time, and possibly forever.

This study was paid for by the pro-pit bull group Maddie’s Fund.

Olson et al.’s chosen DNA test also had an “unknown sensitivity and specificity” and, in general, DNA tests for dog breed are not admissible in court because they are not very reliable, and their reference panels are often very incomplete. Most legal definitions of pit bulls use specific breed information and physical traits to identify breed.

The Hoffman et al. study is also frequently cited by pit bull apologists to suggest that shelter worker labeling practices are inconsistent, but it too suffers from major flaws. For example, no dogs were shown to study participants, only a handful of inconsistent pictures. For that matter, only twenty photos were used, participants were all volunteers, and there was the aforementioned admission of a willingness to engage in lying. For two, the study compares U.S. and U.K. samples, and the U.K. participants are likelier to be less familiar with certain breeds shown and they also cross-classified pit bulls as a breed that is a pit bull breed—the Staffordshire bull terrier, which the authors incorrectly treated as a discrepancy in classification.

Another study cited by pit bull apologists who intend to muddy the waters is Voith et al. In this small study, the authors found zero cases of owners of shelter dogs identifying their dogs as pit bulls, even though two of the twenty had 25% AmStaff ancestry. This study is almost too small to be worth noting, but it suggests, if anything, that pit bulls are being underidentified if we use a substantial minority ancestry definition.

Note: Selection into playing the game is irrelevant here. The point is to discern if pit bulls are able to be differentiated from non-pit bulls, so if the best pit-identifier in the world were the only person in the sample, we could still end up answering in the affirmative.

Members of the pro-pit bull forum who met the other criteria for being in the sample achieved worse-than-chance accuracy, suggesting that they were trying to contaminate the data, unaware that I know where they clicked the link from. If their results are inverted, they identified pit bulls correctly in just under 80% of cases. Good job!

This is arguably a more appropriate adjustment than I’ve stated for a simple reason: the Wisdom Panel DNA test is well-known to misassign pit bull DNA to breeds such as the Rottweiler, boxer, and Boston terrier, among others. You can see the effect of their reference panel updates by visiting the /r/DoggyDNA subreddit and noticing the effects of the update on user results.

If we go the other way and say that pit ancestry is understated in our pit sample somehow—not so likely!—then the effect should be attenuated, but even being generous, the appearance gap is still enormous.

Pitbull is no doubt tired of being falsely accused of biting people. I'm sure he'd be thankful for your clarification here.

Looking forward to next in series!

Another interesting question is: what kind of person typically owns pit bulls? They must have different personalities from owners of other breeds. I’d bet many Dark Triad types prefer pit bulls.