Storks Take Orders From the State

Pronatal benefits and economic booms lead to greater numbers of births

Many people are very critical of the government’s ability to pay people to have children. The skeptical position is so common that, when fertility benefits are mentioned, one invariably earns a retort along the lines of ‘They’ve been tried and they don’t do anything.’

But that is not true. I believe there are at least two key errors supporting the belief.

Fertility Benefit Skeptics Make Causal Inference Missteps

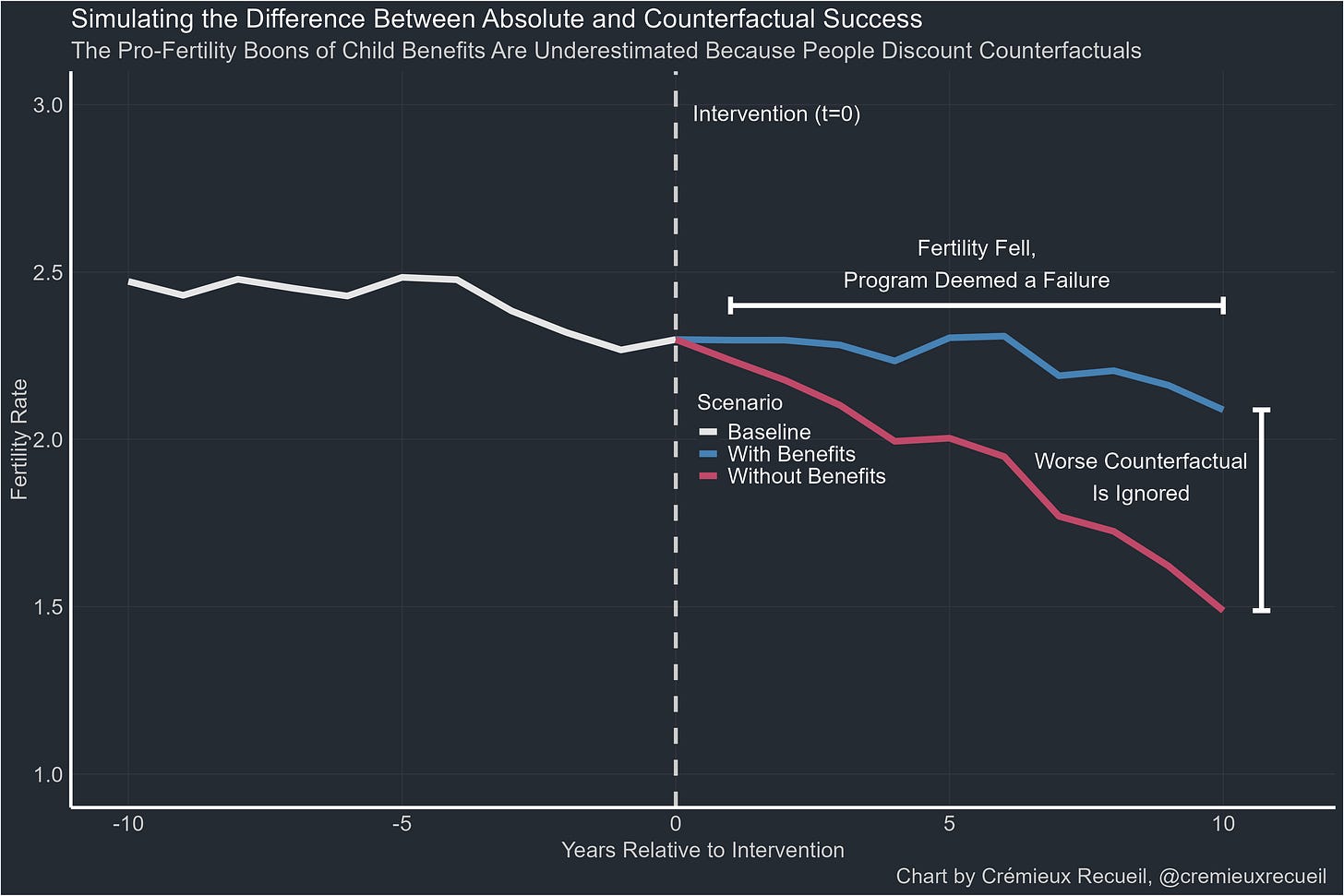

One form of mistake is to consider the wrong estimates of fertility benefit effectiveness. Consider the simulated country with the following data:

The divergent series represent different outcomes for the country if it does or does not implement fertility benefits in year zero. The fertility benefit skeptic sees the series where benefits were implemented and declares “A-ha! They’ve failed!” because the series continued to decline after the benefits were implemented.

But the scenario without benefits has substantially lower fertility than the scenario with them.1

The plain fact is that both series trended down, but one was worse than the other for fertility, and it was the scenario without benefits. The superiority of scenarios with benefits to those without is something you may only be able to see clearly if you’re looking at causally-informative results. Understandably, if you are looking only at cross-sectional data, it can be easy to discount the effectiveness of benefits, because you’ll only see one or the other series, and it’s true that both went down.

This is something fertility benefit skeptics frequently do: they ignore worse counterfactual outcomes to fertility benefits being implemented.

Fertility Benefit Skeptics Don’t Consider Magnitudes

Sometimes fertility benefit skeptics do cite parts of the empirical literature, and if they’re not being selective with their citations, they’ll likely still manage to claim that fertility benefits do not work because the effects are ‘small’, and therefore ‘not worth the cost’. This conclusion is in error for two reasons that have to do with magnitudes.

The first discounted magnitude is the magnitude of the fertility benefits. Lyman Stone has already produced an informative graph that directly addresses the misinterpretation of this magnitude, so I’ll just share it for you all here.

Lyman’s graph shows France, with and without its pronatal child benefits. In the scenario with them, the total fertility rate is elevated by 0.1 to 0.2 points. It’s conceivable that people would view that amount as “small”, but it’s harder to maintain that view after reframing it in terms of existing French lives. Put differently, 5 to 10 million Frenchmen (~7-15% of the total 2023 French population) resulting from these policies is definitely not small.

The second discounted magnitude is the magnitude of the lifetime tax revenues of children. Fertility benefit skeptics seem to believe that child benefits are very costly and children do not provide much in the way of returns to the state after they’ve become adults. This is far from true.

The lifetime tax returns of the typical American are in the hundreds of thousands, while the cost of fertility benefits is a pittance. If someone directly returns $200,0002 to the state while only costing, say, $2,500 per year of childhood (i.e., $45,000), then their existence passes a cost-benefit test with flying colors. Throw in the indirect fiscal benefits of these policy-derived children, and benefits undoubtedly pass muster.

One might argue that the wrong sorts of people—those with low total lifetime tax contributions—would reproduce the most in response to fertility benefits. Fair enough, I’ll accept this point even though I place a high value on human life itself. If the point is true and worrying, simply adjust the benefits so that they’re disbursed through non-refundable tax credits, made available as direct tax reductions, provided with means-testing, provided in-kind as subsidized IVF (which only responsible parents should seek), or so on and so forth. My preferred child benefit setup provides massive inducements to be fertile and multiply without a preference for low-tax births.

Now that we’re equipped with the cognitive tools to keep us counterfactually-minded and aware of the magnitudes that matter, let’s look at and qualify empirical estimates of the effects of fertility benefits.

Benefits = Babies

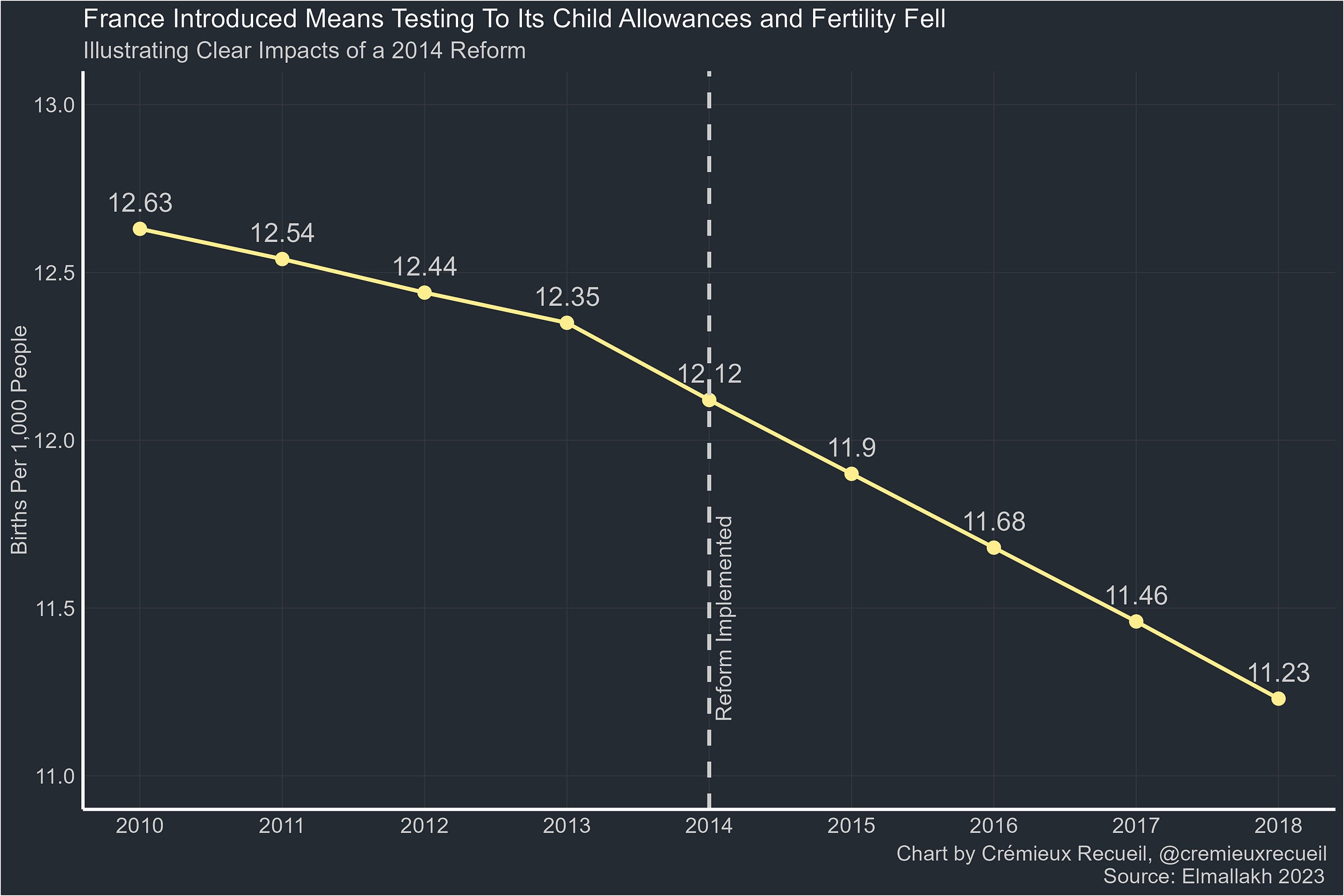

When France introduced means testing to its child allowances, fertility abruptly fell as the rate of decline in the fertility rate increased. This change is unambiguous, and all it took was reducing access to a combination birth or adoption premium, basic allowances, and allowances to support personal and professional life reconciliation.

The nature of this decrease was to change the program from providing unconditional access to the basic allowances (about 180 Euros a month) to only being available in full to the poorest households, with half of the benefit amount being provided to middle-income households and none for the wealthiest French. This wasn’t a big benefit, but it was enough that repeal brought the annual birth rate decrement from -0.76 points to -1.80, then -1.84 the next year, then -1.87 after that, -1.91 in 2017, and finally, -1.94 in 2018.

Similarly impactful reforms have taken place in many locations. For example, in Germany, the government cut child-related welfare benefits to the tune of 18% of welfare recipients’ household incomes in the first year after a baby’s birth.3 The aggregate fertility reduction resulting from this policy was a staggering 6.8% that was immediately felt between the two red lines in this graph, starting in January (first month the reform announcement could affect the birth rate due to abortions) and ending in April (the first month the reform could affect the birth rate through contraceptive use and abstinence).

The wonderful thing about this German study is that it estimated an elasticity for fertility, and it provided a brief literature review covering some other elasticity estimates. Their estimate was 0.38, which was considerable, but much smaller than the 1.3 (Brewer, Ratcliffe and dSmith, 2012), 3.9 (Milligan, 2005), 0.7 (González, 2013), and 2.9 (Cohen, Dehejia and Romanov, 2013) that they cited.

The Brewer paper exploited the U.K.’s 1999 low-income-targeted reforms that increased per-child spending by 50% with a difference-in-differences approach to show that births rose by about 15% among coupled—not single—women. Milligan’s paper leveraged the rollout of Quebec’s broad, pronatalist child benefits of up to C$8,000 to families of newborn children, finding that “the fertility of those eligible… is estimated to have increased by 12% on average, and by 25% for those eligible for the maximum benefit” as well as that an extra C$1,000 of benefits generates a 16.9% increase in fertility. González found that Spain’s universal child benefits led to a considerable 6% increase in fertility in response to an 8.3% increase in income, driven by reduced numbers of abortions. The Cohen paper observed that reducing Israel’s child subsidies by the equivalent of 3.3% of income reduced fertility by 9.6%.

In a study of the fertility impacts of a universal child transfer in northern Norway, the state covering 58% of the expenses of a child’s first year of life (12% more than normal) increased the odds of a child among those in their 20s by five percentage points. There was also an increase in the percentage of those with three kids of 1.4 percentage points.4 The effect pushed up fertility among those who were unmarried, but it didn’t seem to increase poverty.

In South Korea, municipality-level childbirth grants and allowances have clear positive effects on fertility. A 10 million won—or about $8,000 at the time—increase in family benefits comes with a 3.5% increase in total fertility. The authors projected that, to return Korea to a fertility rate of 1.5 children per woman (from about 1 per woman) would therefore require subsidies of about 44 million won per child. This is very large and likely unworkable, so they should do something else, but at least it’s apparent that Koreans are not immune to fertility incentives.

The Argentinian government initiated monthly roughly $50 cash transfers to households without workers in the formal sector, leading to about two percentage points higher fertility among those with a child already, and no impact on the childless. Comparing mothers who were eligible to those who were ineligible, the result of the program looks fairly dramatic:

The implementation of Quebec’s Parental Insurance Plan gave the province a more generous version of the Canadian federal Employment Insurance program and led to a considerable bump in fertility. For those without secondary education, fertility increased by 17%; for those who completed it, the jump was 46%; for those with university diplomas, there was a 27% increase in fertility. The effects are quite dramatic and shifted Quebec’s fertility above Ontario’s:

Across different countries and contexts, we see consistent evidence that transfers generate increases in fertility that are sizable in magnitude. In a 2021 review of various pronatal policies, the section on transfers repeated much the same: “Overall, there is quite solid evidence that increases in transfers have an immediate effect on fertility” and this effect was generally sizable. Similarly, Lyman Stone estimated an elasticity of fertility to a 1% increase in income of between 0.04 and 0.30.

Leveraging Lyman’s estimates, the elasticity to the private value of having a child—defined here—would be $287,800/$80,610 (inflation-adjusted ages 0-18 cost of childrearing5/household income) in 2023 = 3.57 * 0.04-0.30 = 0.14-1.07 (median = 0.47), thus justifying massive spending for even well-below median performing pronatal programs.6

But even this heartening level of efficacy should be qualified as being unduly pessimistic for a simple reason: relatively effective and ineffective policies are being lumped together to produce those elasticity estimates. Family leave policy, for instance, tends to be less efficacious for promoting fertility than transfers. Pessimists towards pronatal policy tend to gloss over or exploit ignorance about this distinction.

In the piece whose title prompted this one’s, the author wrote “The amount of money required to trigger even these small effects is enormous… ‘one extra percentage point of GDP spending’ on early childhood education and child care programs was ‘associated with 0.2 extra children per woman.’ In the U.S., where the 2022 GDP was $25.46 trillion, that would mean spending more than $250 billion.” Sadly, this conflation of relatively more and less efficacious programs was not addressed in that now well-cited article.

The issue of endogeneity when doing cross-country comparisons was also not dealt with at all in that article. That is to say, the author seemed to notice that different countries had different policies and that they were ending up with different fertility levels, but was much less interested in evaluating where their fertility situations would be with different sets of policies. As the bulk of the evidence in the literature indicates, however, pronatal policy definitely works. Each country implements different policies, in different ways, in different pre-existing fertility regimes, so we should expect those places to function—in a word—differently, preventing simple, cross-sectional pooh-poohing of the policies implemented in different countries.

Someone who is serious about whether pronatal policies work would not ignore this issue. Instead, they would cast aside simple claims like ‘Hungary does a lot of pronatal policy and their fertility is poor, so it must not work!’ The reality, described here, is that Hungary’s pronatal policy is gimmicky and excessively targeted, making it predictably ineffective because the policies do not correspond to anything like best practices. Hungary may appear to be ‘all-in’ on pronatal policy and struggling, but that hardly means a thing when going ‘all-in’ looks so different from what a competent planner would recommend. To get an example of what implementing empirically well-supported policy does, look no further than Mongolia. Mongolia was able to adopt simple fixes corresponding to a best practice from the literature and they saw a sizable and sustained bump in births.

This is not to say that transfers are the only things that should be part of effective pronatal policy.7 Family leave policies do still tend to work,8 childcare policies do still tend to work, and healthcare policies do still tend to work. The efficacy may be more limited for these measures, but it’s unlikely that anywhere currently struggling with sub-replacement fertility will get their fertility rates up to acceptable levels without engaging in many measures like these, in addition to becoming more pro-housing9 and pro-growth, because growth, as it turns out, matters.

Booms = Babies

I have seen way too many people conclude that this graph shows that income barely matters for fertility.

But… why? If we increased the incomes of anyone along these ranks, their fertility might increase. Just as endogeneity plagues international comparisons, so too does it act as a bugbear for comparisons like these. But, as a simple test, when men win the lottery their fertility tends to increase. In that case, men was italicized with reason: lottery wins had no effect on fertility for women, seemingly because they had greater rates of divorce after they won. Contrarily, men had significantly lower rates of divorce and higher rates of marriage, presumably mediating their increased fertility.10

This finding holds up in natural experimental settings.11

As we know, women tend to want more kids than they have, and indeed in many places with sub-replacement fertility, they want more than enough to beat the replacement level.12 So, are women lying? Consider the paper’s first result: comparing similarly-educated women living in similarly-expensive locations, completed fertility was positively correlated with husband’s income:

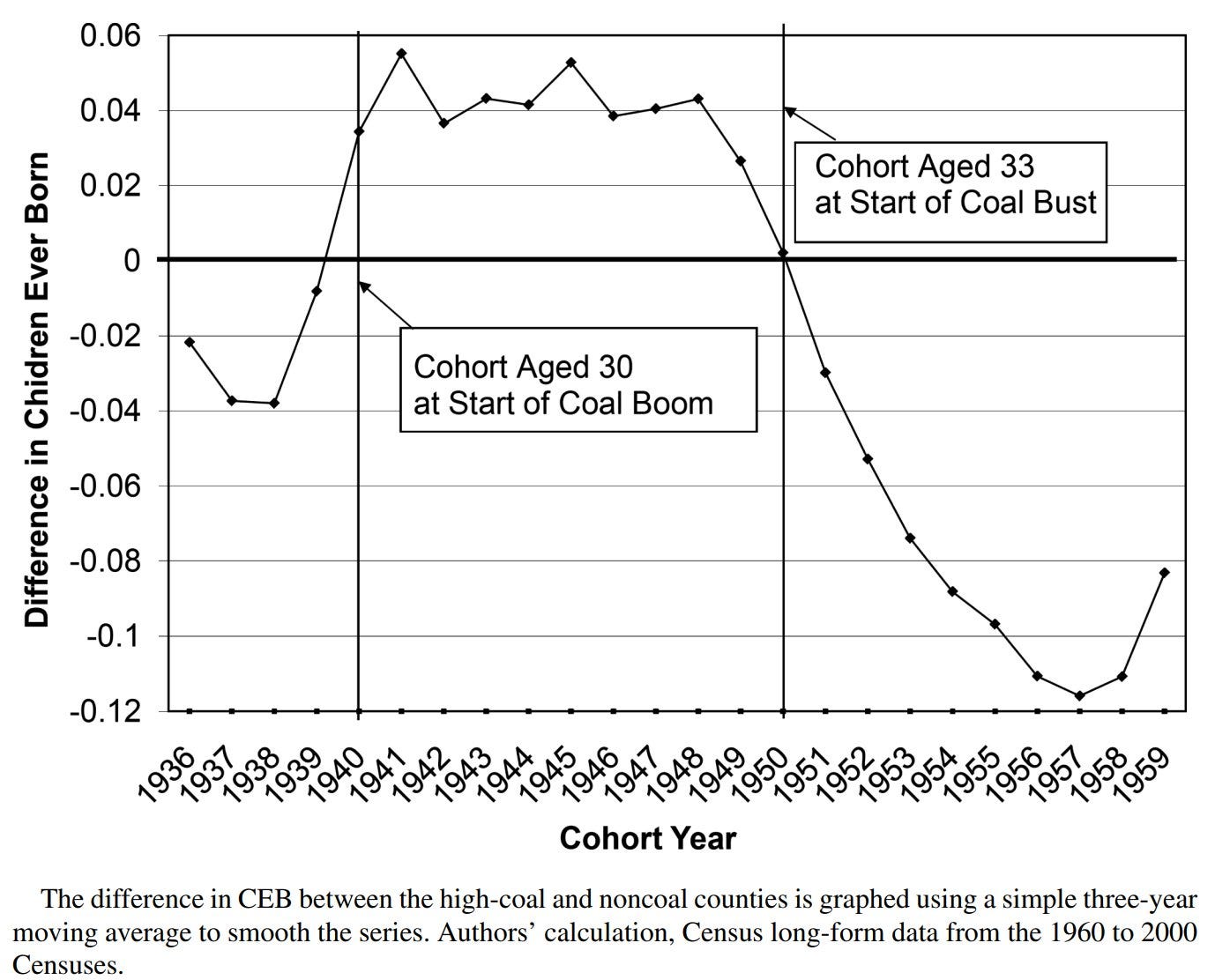

This finding might be down to selection into marriages. So, how could we address this? With a shock! And specifically, a shock that should predominantly have its impacts on women's socioeconomic outcomes through their husbands. Luckily, we have OPEC. Or more specifically, we have the coincidence of the U.S. having burdensome domestic regulations and OPEC embargoing it, causing the price of an alternative energy source—coal—to explosively increase after holding steady throughout the 1960s.

The Appalachian coal boom clearly favored the employability of males, as women weren’t going to be heading into the mines. So, as the crisis set in and coal prices spiked 44% between 1973-74 before stabilizing at twice their price throughout the 1960s, the status of men rose. But after the boom came the bust in the 1980s, as other energy sources were secured, and by 1990, the price of coal had returned to the level it was at in 1970. The boom, the peak, and the bust had clear effects on worker earnings and employment:

Relieving the economic constraints felt by these workers turns out to have been very good for fertility. Adding them back turns out to have been very bad for it. Those males who experienced the boom had greater fertility, and those who experienced the bust had much worse fertility:

This finding speaks to the fact that women are not lying when they say they want more kids than they have right now. Their fertility is just mediated in complex ways that lifting economic constraints might help to remedy. Focus on growth—but perhaps not on redistribution to women—and we may just lift them and get more babies in the process.

Others have investigated this thesis and variously found that higher economic growth comes with greater fertility rates; that major sources of economic disruption like Brexit and the COVID pandemic are likely to harm fertility rates; that the ebb and flow of the business cycle and the harms of major recessions affect fertility predictably; etc. And these things are sensible, because raising incomes leads to higher fertility.

Social Multiplication

Everything I’ve said thus far is liable to undersell the benefits of fertility policy because people are social. For instance, in China, ethnic minorities exposed to exogenously lowered Han fertility reduced their own fertility. If this were reversed, and fertility rates went up, the general desire for kids would probably go in the other direction, increasing instead of decreasing, by some margin.

People raised with more kids in the family also tend to want additional children of their own. Raise the average size of families, and you’ll raise expectations and resulting rates in lockstep. Even signing people up to take care of infant simulators seems to increase pregnancy rates:13

These effects are only sometimes contained in estimates of the benefits of different pieces of pronatal policy. If they were encapsulated in all such examples, effects would likely be even larger across the board. In short, what I’m saying is that the more we raise fertility, the more it’s liable to rise and self-sustain due to these sorts of knock-on effects. The amount of intervention required for a given boost or level target might fall with time, or it might become more effective as the willingness to have children in response to some stimulus falls. Who’s to say? We can only know if we try.

Governments Should Be Willing To Do and Pay A Lot

I’ve briefly summarized a great deal of evidence, but I hope I’ve made it clear that the fertility rate is plastic in response to efforts to raise and lower it. If countries go all-in on credible on pronatal efforts, they can raise fertility rates by substantial margins. This evidence is so strong that, using the median elasticity above, it’s likely that the U.S. could raise its fertility rate above replacement while spending around 3% of its GDP, and it would still economically benefit substantially because the returns would exceed the costs almost three times over, and that’s not even accounting for the benefits from society becoming younger and more dynamic.

If the U.S. focused on economic growth in a more extensive, pro-family way, the required spending on fertility programs would be even lower, while the returns would be even higher given growth means socially raised productivity.

There is simply no need to be pessimistic about fertility policy, and yet, pessimism is the norm. I believe there’s no good reason for that. The reasons are variations on a theme of poor inference and poor grappling with the evidence. But with a clear mind and given all the evidence, the conclusion is clear: If we try, we can easily succeed.14

The real number is above $500,000, which can easily cover things like the cost of schooling and public services consumed as children.

Sandner and Wiynck, the authors of the German study, concluded by noting that the fertility response “found among welfare recipients… seems to be weaker than that of general populations.” Similarly, Reader, Portes and Patrick found that the U.K.’s limitation of means-tested child benefits to the first two children in a family led to perhaps a meager 0.7% lower fertility rate, or a 10% decline in relative terms, with perhaps a 16% reduction in the odds of having a third child. Why the small effect? Perhaps because there was poor awareness of the policy.

A related fact may be that fertility policy will tend to be less effective for the very poor in general, as their kids are more often unintended. Healthcare policy, as it turns out, may help to remedy this by increasing the number of intentional births and reducing the numbers of unintentional ones.

There is very little reason to believe that fertility policy will be ‘dysgenic’ as it were.

Notably, if the benefit is IVF—the costs of which are relatively modest—, then we probably overestimate costs and underestimate benefits right now due to age-related changes in the success of IVF. Specifically, IVF works better for younger couples, meaning that if IVF is subsidized when it’s relatively more expensive in people’s lives, we should see greater success rates and lower spending on it and attendant procedures. If financial support is provided shortly after infertility diagnoses, the costs could be shrunken relative to the benefits even more greatly with a public subsidy for assisted reproductive technologies. Ben Podgursky is the one who pointed this out to me.

It is worth noting, but not very relevant here, that the evidence that transfers work in already high-fertility environments is generally negative. Although they may still be effective at relatively high, but still much lower, levels of fertility.

Emil O. W. Kirkegaard recently compiled some studies on this topic, but came away with different conclusions. I believe this is due to a different reading. See also, this.

This replicated a finding from the U.S.

Notably, ‘ideal fertility’ numbers are plastic and change in response to income changes, numbers of children people have already, numbers of children people are exposed to in the community and family, etc.

And because immigration is not a sustainable way to growth the population given falling global fertility, it must be pursued.

The fundamental problem is that one party has become the pro-birth party and the other has become the anti-birth party. This is because married middle class people (especially with 3+ kids) have become solidly republican, while the Democratic Party is the party of poor single moms, non-straight people, and low fertility professional urban women. With some additional support from people employed in the Eds and Meds racket.

So the lefts fertility policy usually amounts to means tested giveaways to poor single moms and additional funding for Baumol's cost disease Eds and Meds rackets that don't return much value.

The right in theory should be pushing huge tax breaks for middle class married couples with multiple kids, but it can't seem to get the message.

I'm skeptical we will get bi-partisanship on this because of the policy differences, but I'll take whatever tax breaks I can get.

I know this is just an anecdote, but at my church everyone has kids. And so all the newlyweds start having kids right away. I suspect from this experience that childbirth is surprisingly sensitive to peer pressure.