The Cultural Power of Elite Immigrants

A Slaveowner, a Nazi, a Lutheran, a Jew, and a Forty-Eighter Walk Into a Voting Booth

Richard Hanania has kicked up a lot of dust about the issue of immigration and IQ. His June post on the topic argued there’s not much value in focusing on IQ when it comes to immigration; he even remarked that diverse immigration may be good because it limits social cohesion, promoting markets in the process.

As befits such a provocative post, it inspired a handful of responses right off the bat.1

Was Hanania Right?

The title of this section actually doesn’t have much to do with Hanania’s essay aside from a single part: should we care about IQ when it comes to immigration? Sebastian Jensen said so in his response to Hanania when he wrote

I don’t think there is a good case against highly skilled or powerful immigrants who contribute resources and good genes to their destination. What I do think there is a good case against, is the policy of importing hordes of unskilled and poor immigrants who do not contribute to their destination’s gene pool. This is because an individual’s characteristics contributes to not only their own lives, but the lives of their countrymen as well.

Sebastian’s remark sounds like one of the most common takes made by people who wade into this area: high-IQ immigration is good. The people who endorse this take often don’t care about where the high-IQ people come from, they just want the immigrants to be high-IQ.

But if you had to pick between high- and low-skilled immigration and your goal was to maintain your institutions and culture, there’s a solid case for avoiding high-skilled immigration.

Allow me to begin with two important facts.

The most important reason kids’ politics resemble the politics of their parents and siblings is additive genetic influences. The variance supplied by shared sibling environments, twin-specific environments, vertical cultural transmission, and gene-environment correlation is minimal. Additive genetics, measurement error, and unique environments are the dominant sources of variance in political views, in that order.

Actually that’s wrong. But it’s also right. The truth is, most people don’t have an ideology. Their views are kind of random and they become less random when issues become popular.2 The people who do have an ideology are smart people. This is such a powerful observation that the heritability of political ideology is only really high when twins are knowledgeable. When twin pairs are low-knowledge, their family background actually seems to matter more. Since people aren’t broadly exposed to many issues—and especially those that become popular after they move away from home—through their family backgrounds, their particular views are often noise or family hearsay when they’re not that bright.3

This matters because this means the people who can bring an ideology with them are elite immigrants, and low-IQ immigrants are not going to bring an ideology with them since they probably don’t have one to bring. High-IQ immigrants, on the other hand, will often have ideologies, and they will tend to bring those ideologies wherever they go; assimilation is not the norm.

High-IQ immigrants will have major impacts on the places they end up not only because they have an ideology, but also because being a high-ability individual gives them the power to influence places so that they end up more in line with their ideology. This can, of course, be both good and bad, and opinions about what cognitively elite immigrants do will differ. But that elite immigrants have major effects is doubtless.

Let’s go through some examples.

The Nazis

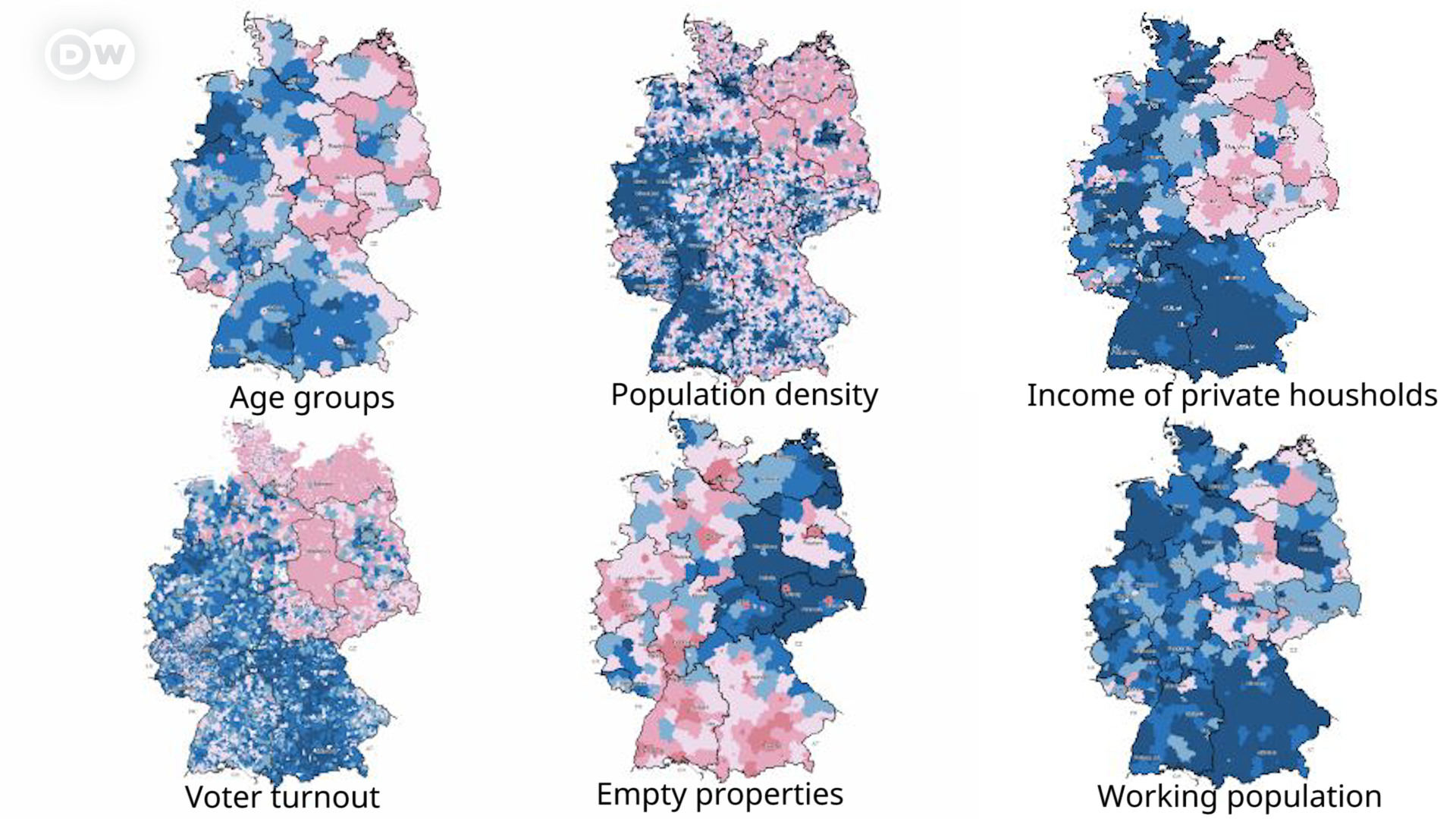

Germany today is characterized by a persistent divide in prosperity and politics between its east and its west. In fact, there’s an east-west divide on shockingly many metrics.

These divides—and many more like them—are mostly a holdover from the east’s recent communism leaving it underdeveloped and culturally crippled. It’s currently possible to produce decent measurements of GDP with nightlights. To that end, we can see the impoverishing power of communism very clearly by looking at Berlin:

But everyone knows about Germany’s east-west divide, so it’s not particularly interesting. People are substantially less likely to know that Austria was also divided between the Soviets and the liberal democratic allies. The occupation map was remarkably similar to the one for Germany:

Unlike Germany, Austria was didn’t remain split until the fall of the Soviet Union. Instead, it became free shortly after the signing of the Austrian State Treaty in 1955. Nevertheless, ten years of Soviet occupation still had an effect, and luckily for us, it had an effect that has been studied.

When the Allied occupation began in the summer of 1945, the state of Upper Austria was unexpectedly split between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. For military reasons, locations north of the Danube that were liberated by the Americans were passed into Soviet hands. Before that transition took place, rumors began circulating that the switch would happen, and people in the soon-to-be-Soviet zone began to pack their bags so they could head over to the region of U.S. control. Because the people knew about the horrors of communism, the barbarity of the Red Army, and they had been exposed to anti-Soviet propaganda for the preceding decade, the number of people who fled was substantial.4 As recorded by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services:

On 2 July 1945, a rumour circulated in Linz that the Russians were to take over the area north of the Danube. That night, people started crossing the Linz bridge into what was believed would be the future American zone […] One MP officer estimates that 25,000 persons crossed over, but [an] informant claims that 4000-5000 is a more accurate figure. Informant estimates that another 4000-5000 crossed on July 4. […] Two informants who made a trip to the area north of the Danube report that what appears to be a general exodus is in progress.

In most places, members of political parties are relatively elite compared to people who are not members of political parties. This was probably no less true in Nazi Germany than it is in, say, Communist China today. The migration south into the U.S. occupation zone was also selective—it selected for Nazi party members.

The Nazis in Upper Austria likely feared reprisals since in February of 1945, their members had hunted down and slaughtered nearly 500 Soviet POWs in the Mühlviertler Hasenjagd, the “hare hunt” following the Soviet breakout from the Mauthausen concentration camp. Accordingly, historians, political scientists, and even contemporary journalists recorded that “Nazis in particular feared being punished more severely by the Russians and escaped with their belongings to southern Upper Austria.”

This swift and selective migration was not only selective with respect to Nazi party membership, but among Nazi party members as well. The result was that the number of registered Nazis and Nazi elites varied considerably across the Danube, such that there were 53% more Nazis in general and 182% more Belastete per capita in 1947.

These numbers represent majorly selective migration, and they came with major effects. For example, by comparing the surnames of 17,000 political candidates in Upper Austrian local council elections, Ochsner & Roesel were able to identify the overrepresentation of surnames from the Soviet zone among far-right candidates in the 2015 elections that took place in the U.S. zone. Thus, these migrating elites carried their politics over the river with them and they then proceeded to maintain their potentially pernicious politics over no fewer than three generations.

This is an especially incredible finding when the Allies political consolidation of Austria is noted. Immediately after the second world war, the Allies banned the Nazi party and helped to refound the social-democratic SPÖ, the conservative ÖVP, and the communist KPÖ. They also kept 535,000 former Nazi party members from participating in the first post-war elections in 1945, and the formation of far-right parties was forbidden. But this repression began to end with the amnesties that were promulgated starting in 1947, which culminated in around 90% of registered Nazis being allowed to vote in 1949. One of their first actions was to form the Federation of Independents, or VdU, the predecessor of the modern-day FPÖ. This party was the first far-right post-war party, and it did surprisingly well before being torn apart by internal argument. Regardless of its ultimate fate, it serves as an indication of political continuity and history—with the pre-war Pan-German movement—in far-right politics in Austria.

The enduring influence of these migrating elites is extraordinary, and Ochsner & Roesel showed this with a regression discontinuity design. But before getting to that, it’s reasonable to suggest this migration didn’t have a causal effect, and the impact of migrating Nazi elites on later political outcomes was a result of, say, some other historical contingency associated with the geography of the Soviet-American split of Upper Austria. This is unlikely for many reasons.

Firstly, the U.S.-U.S.S.R border is plausibly exogenous, as the Danube was never a historical border in this region and the division was unforeseen prior to the occupation plan announcement on the 9ᵗʰ of July in 1945. The division was entirely driven by military considerations on the part of the Soviets; namely, they wished to maintain full borderline access to Czechoslovakia. Perhaps, though, the coincidence of the Soviet zone with one of Upper Austria’s historical regions, the Mühlviertel, is the driver. This also seems unlikely, as the historical regions never self-governed and the administrative boundaries of this region are only partially coincident with the Soviet occupation zone, both before and after the second world war. Even the modern-day NUTS-3 regions in Upper Austria don’t correspond with the Mühlviertel. But just in case, Ochsner & Roesel used the Innviertel as a natural border (the Traun river) for a placebo test.

Secondly, municipalities could not have manipulated assignment into the American or Soviet zones. Allied zoning didn’t consider Austrian requests, so self-selection is not a possible identification threat.

Third, several variables vary smoothly between the pre-treatment and post-treatment periods, including sociodemographic variables, economic structure, unemployment rates, tax revenues, eligibility for EU structural funds, geography, voter turnout, and referendum outcomes. The discontinuity generated by migrating Nazi elites is a unique exception.

Identification of the effects of Nazi elites on modern politics in Austria is credible. In 1930, there was no split in far-right vote shares across this boundary:

When we fast-forward to 1949, the far-right vote shares are split across the river, even though by this point, the Soviets had no time to do anything but induce Nazi migration:

And now, in the modern-day, the persistence of the effects of this migration are still pronounced:

Non-migration mechanisms are generally not plausible. For example, there was negative evidence that the apparent effect of Nazi migration was really due to migration in general—as indicated by refugee camps and municipal population growth—, that the effect was driven by denazification efforts—as indicated by the increase of the electorate in national elections in 1945 to 1949, which proxies for the relative numbers of amnestied Nazis until 1949, and lagged municipality pan-German vote shares in the last election prior to the second world war—, that the effect was driven by allied bombings—as indicated by municipality-level narrow, broad, or neighbor bombings—, or that the effect was driven by local ÖVP efforts to hinder the formation of far-right parties—indicated by 1945 ÖVP vote shares or the same year’s vote share margin between the ÖVP and the SPÖ. The most obvious potential mechanism is something that the Soviets did during their occupation, but this is unlikely because the results for Upper Austria diverge from the results for the Soviet portion of Vienna, which ought to have had the same or at least similar Soviet policies, but did not have a recorded history involving mass Nazi elite migration to other parts of the city because the Soviets occupied the entire city momentarily in July 1945. In Vienna, there just seems to be nothing; whatever unobservable policy effects the Soviets might have had just aren’t there.

Places Nazis ended up had a greater supply of far-right party offices, and a greater demand for far-right parties too.5 The demand effect of Nazi migrants may have even been multiplicative: Ochsner & Roesel were able to use 1949 election data to calculate that losing a Nazi in northern Upper Austria came with a loss of 1.3 far-right votes, but gaining an additional Nazi in southern Upper Austria came with a gain of 2.5 far-right votes. As such, Nazis must have been capable of exerting influence beyond their own votes. In the then most recent election, Nazi descendants were able to leverage their beliefs to southern voters by a factor of 1.8.

Elites matter—they really do! The migration of Nazi extremists within Austria had a persistent impact. The authors concluded:

[Not] only [do] migrating extremists themselves but also particular institutions founded by migrating extremists… have persistent effects in the long term. Our study on local party branches shows that extremist communities can preserve ideologies even when outside conditions temporarily change. We find stronger effects in remote and larger municipalities that indicate anonymity and segregation—something that applies to many European suburbs [today]…. [Societies] might well seek to prevent the infiltration of extreme ideologists, for example, fighters returning from the so-called ‘Islamic State’, who are able to share and spread their beliefs.

These conclusions aren’t without precedent. Many ideological radicals have traveled the globe to spread their values, like Mikhail Bakunin and Che Guevara. Governments rightly fear these people and make efforts to limit their movements, inconvenience them, and monitor the things they do. Karl Marx serves as an excellent example, because he was banned from several countries before finding himself in London. The U.S. and several European countries also forbade the return of citizens who fought for International Brigades in the Spanish civil war. ISIS is simply the latest example of an ideological organization whose members governments have been seeking to cut off.

But elite influence isn’t all bad.

The German (-Americans)

The man seen above is one Carl Schurz, an American revolutionary born in 1829.

That’s not to say he was involved in the American Revolution. After all, he was born half a century after it, so how could he have been? The technicality that makes him an American revolutionary is that he was an American—the 13ᵗʰ Secretary of the Interior under Rutherford B. Hayes, in fact—and he fought in the German revolutions of 1848-49.

These abortive revolutions were part of a wave of uncoordinated revolutions by primarily liberal but also some radical elements, that swept across Europe, leading to violence in Italy, France, the German states, Denmark, the Austrian Empire, Switzerland, Poland, and Romania, with more minor uprisings and unrest elsewhere. In most places, these revolutions were at best moderately successful, resulting in a subset of their goals being reached. In the German states, a major result of their eventual failure to bring about their goal of human rights guarantees, democracy, and a unified Germany was that thousands of these political revolutionaries fled to Brazil, Chile, Australia, safer parts of Europe, and the United States.

Not only did these revolutionaries flee, they were often the subject of exile and expulsion. For example, in German lands, many death sentences and prison terms were commuted for revolutionaries who opted to leave forever. In Hesse, revolutionaries were explicitly given the choice between sentencing or going to America. In Württemberg, judges asked revolutionaries if they wanted to go to America or serve their sentences. If they chose America, the journey was subsidized.

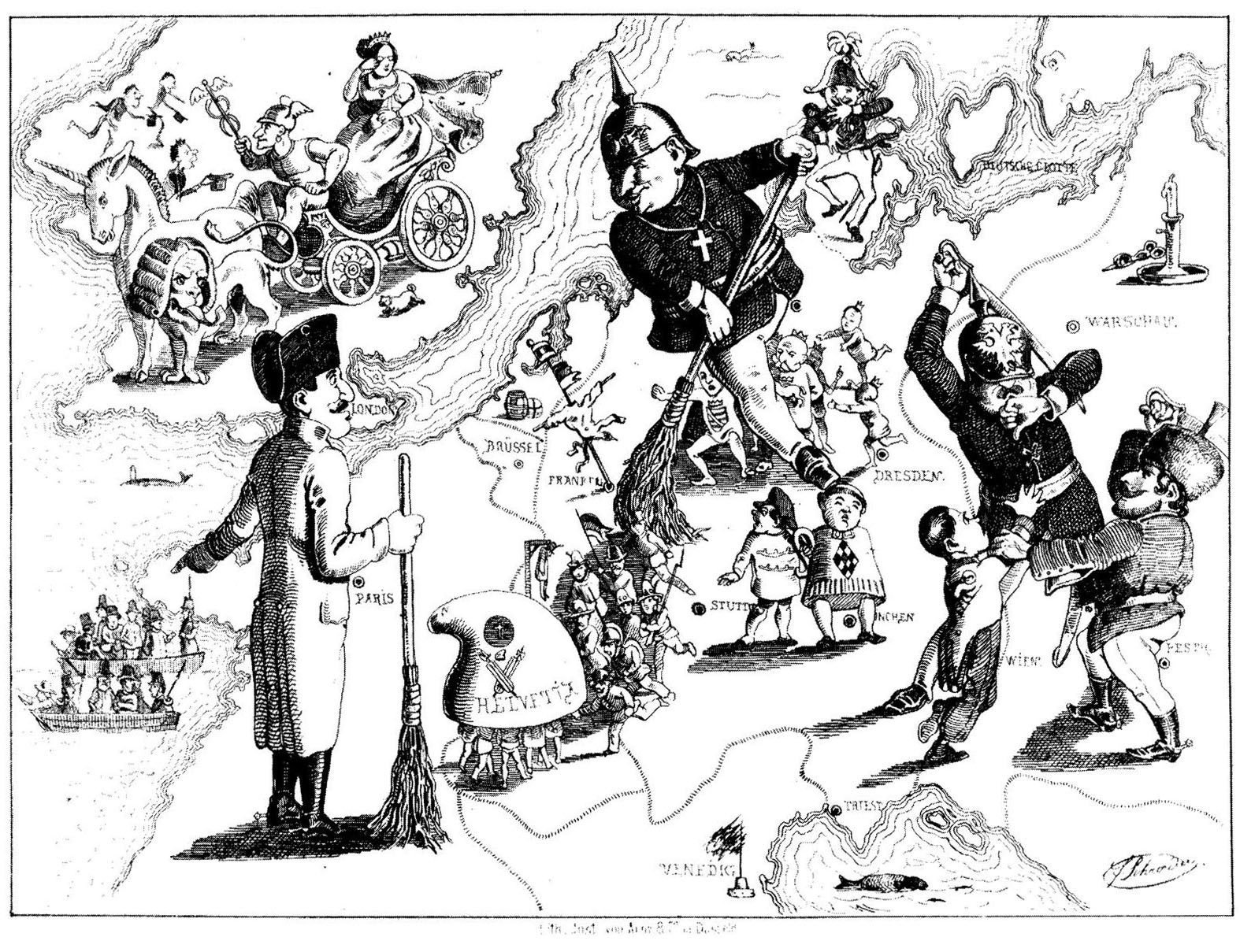

Some of the revolutionaries from Baden escaped to Switzerland after they failed, but despite being republicans with sympathy for the revolutionaries, the Swiss didn’t want to put up with the pressure to return them from the French and Germans, so the Swiss parliament passed an act expelling fourteen revolutionary leaders and their followers. This act wasn’t cruel. In fact, the Swiss negotiated on the part of these revolutionaries so they could depart from Le Havre to the U.S. with the Swiss footing the bill. The Germans also made sure return would be difficult by circulating “black lists” of the revolutionaries for the purposes of intercepting anyone who might come back. This expulsion is depicted in this political cartoon entitled “Rundgemälde von Europa im August 1849”, where absolutist rulers are shown sweeping Forty-Eighters out of Switzerland and away from European shores.

These men, known as the “Forty-Eighters”, were largely educated, ideological liberals. To be sure, they weren’t all from Germany. Czech, Hungarian, Irish, French, and Polish Forty-Eighters have numbered among America’s notables too. But the German states were the largest source of these relatively elite immigrants who would go on to constitute about 10% of the entire Union Army in the Civil War.

The German Forty-Eighters that constituted the majority of the revolutionaries who settled in the U.S. arrived and immediately began to found newspapers and social and political clubs, started to give public lectures and agitate for their values, and enlisted en masse in the military. When they arrived they had nothing, no destinations, no social networks, no family ties, nor much relevant language experience. The German Society of New York recorded their arrival as a massive “increase in requests for assistance to people totally deprived of all means, mostly political refugees flocking to America after the failure of the revolutions.”

In spite of their initial poverty, Dippel & Heblich noted that though these immigrants were initially being relegated to the same largely menial jobs other German immigrants worked, they “quickly put down their picks and shovels and started working in teaching, journalism, publishing, or the arts.” In other words, these political refugees were more elite than other German immigrants, and they realized that status shortly after arrival.

Dippel & Heblich recorded additional impacts of notable Forty-Eighters including a massive effect on Union Army enlistments. In fact, the presence of Forty-Eighters in a town increased enlistment by a staggering 66-67%. This finding was robust to a variety of controls, propensity score matching, the use of state and county fixed effects, interpolating enlistment locations, and permutation testing. More interestingly, through perusing the biographies of Forty-Eighters in the sample, Dippel & Heblich were able to ascertain that more “politically active” Forty-Eighters generated more enlistments. They also reaffirmed the selectiveness of Forty-Eighters relative to other German immigrants by showing that non-Forty-Eighters in the 1848-52 German arrival cohort didn’t affect enlistment.

To further justify the causality of the effect of Forty-Eighters, Dippel & Heblich used an instrumental variable strategy, where they leveraged the listed destinations of their co-passengers for the voyage, since other passengers are highly influential given the amount of time they spend together. This and another instrumental variable strategy leveraging Forty-Eighters’ first jobs at their port of debarkation as an instrument for their pre-Civil War locations led to similar results.

The mechanisms through which Forty-Eighters influenced enlistment were evaluated in several ways. The first method was non-causal, so it’s suggestive. This method was mediation analysis, which indicated that Forty-Eighters’ influence was mediated by the presence of German newspapers and Turner Societies (Turnverein), German gymnastics clubs. These might explain a quarter of the baseline effect of Forty-Eighters on enlistment. Causal estimates were provided through event studies. The first event study variety was based on Forty-Eighters organizing speeches, rallies, concerts, encouraging enlistment, or organizing other anti-slavery events. These proved probable mediators, as these civilian acts of leadership caused enlistments to increase by 60% the week they happened and the week after, before the effect disappeared. The other type of event study was based on personal enlistment. Young men would often enlist together in hopes of being set up as a single military unit. It just so happened that when Forty-Eighters enlisted, the groups they brought with them were much larger than normal. Before a Forty-Eighter would enlist, there was no enlistment pre-trend, but then enlistments would increase by 70% in the week they did, followed by 40% in the following week and a return to normality thereafter.

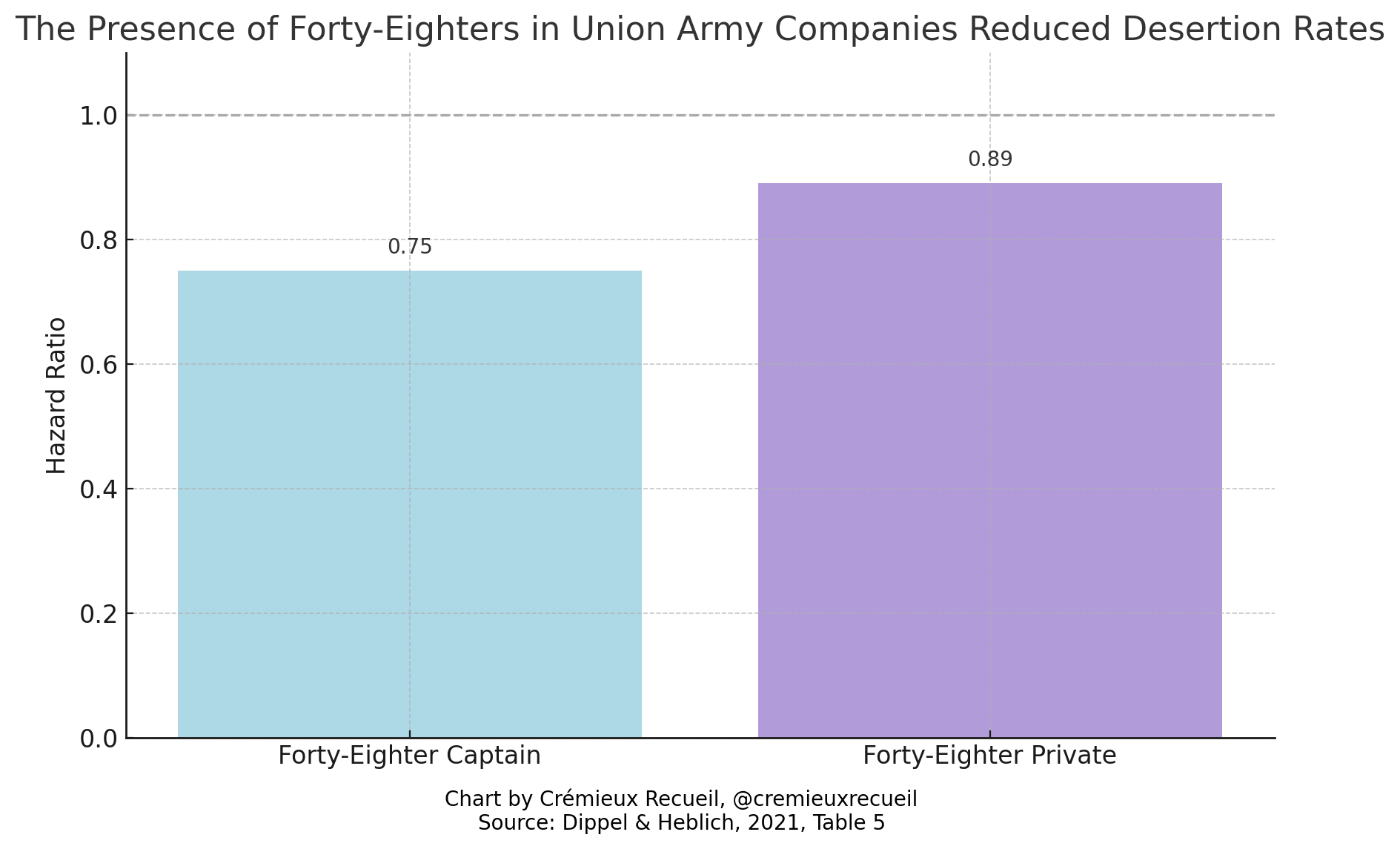

Enlistment is only one side of the coin when it comes to military participation. The other is sticking with it, and for that outcome, Forty-Eighters also mattered. In fact, having a Forty-Eighter assigned to be a company’s commanding officer significantly reduced desertion rates by somewhere between 23 and 31%, while having a Forty-Eighter as a private in a company had a quantitatively smaller but still significant influence, reducing desertion rates between 11 and 17%.

Some other variables had notable influences on the desertion rate, like the year of enlistment—the earliest enlistments were the least likely to desert, reflecting their enthusiasm to sign up—, ancestry—Americans abandoned least, followed by Germans, then Scandinavians, then Irishmen, then other immigrants—, and ancestry fragmentation in a company—ethnically diverse units had more abandonments, presumably because of something like that camaraderie is easier with people like yourself, especially when there are language barriers.

The differences in commitment to the war were actually very obvious, in part because of the overrepresentation of Forty-Eighters in the Union Army. Forty-Eighters were ideologically committed to the view that America was the greatest hope for republican government, so they were willing to fight for it. That’s why the desertion rate for Germans—all of whom were not Forty-Eighters—was ‘only’ 20% higher than the norm for Americans, which seems good when it’s realized that the rate was 47% higher for Scandinavians, 68% higher for Irishmen, and 99% higher for other immigrants. Or, visually:

Some effect of Forty-Eighters was permanent. For example, consider the NAACP. After its founding on Lincoln’s 100ᵗʰ birthday, it was, for a long time, the only national political organization whose goal was to advance the equality of Blacks. Because February 12, 1909 is substantially later than the arrival of the Forty-Eighters, the fact that towns that had Forty-Eighters were 22-23% more likely to have NAACP chapters suggests that the impacts of these elite immigrants carried on into future generations.

The Forty-Eighters weren’t the first great Germans, nor the last. In fact, many of the Forty-Eighters were Protestants, like another great German, Martin Luther.

Luther’s Disciples and the English Scientific Revolution

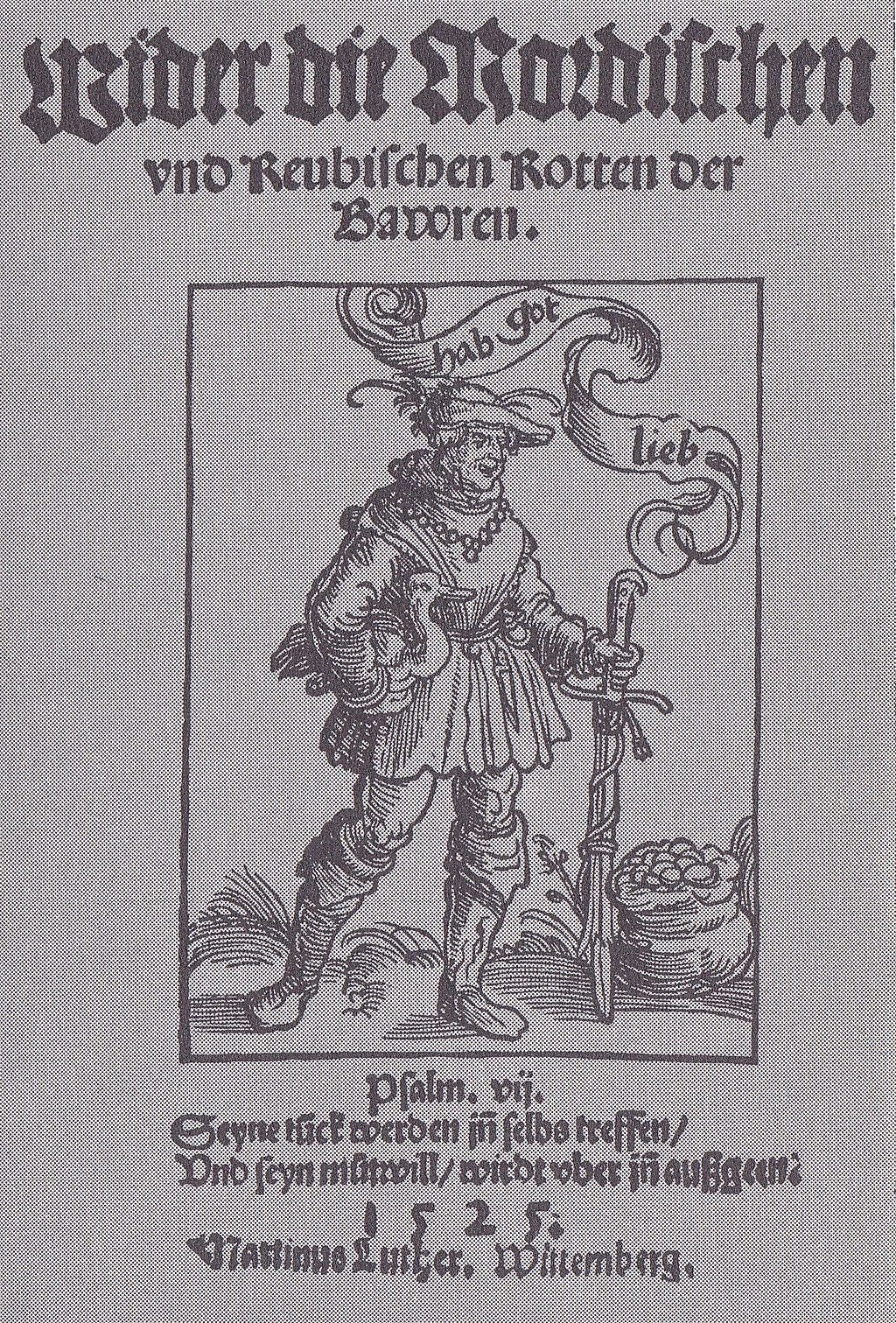

Allow me to show you my favorite piece of Martin Luther’s writings:

This is what I consider to be Luther’s most cynical writing. In English, its title is “Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants”. This tract condemns the peasants participating in the Deutscher Bauernkrieg, a popular peasant uprising that was likely incidentally fomented by Martin Luther himself, as he was considered an icon of upheaval by the mass of peasants, given his own repudiation of Catholic doctrine. Since Luther was reliant on the patronage of lords and ladies, he likely wrote this text to cover his own backside. If he didn’t, he might have been seen as siding with the peasants, spelling his doom if one of his benefactors was affected.

Regardless of your thoughts on the man, it’s fair to say he was a genius in the particular sense that he had inspiring and meaningfully novel thoughts that led others to take action. This much is obvious if you live in the real world and you’re aware that Protestants still exist and they’re very important. Luther’s travels and communications are so well-evidenced that we know he inspired others directly, too. Like any visionary worth recording, he must have influenced people in some indirect sense, but Luther’s brilliance was greater because he not only promulgated an idea and set a change in motion, he also had a hand directing his reformation.

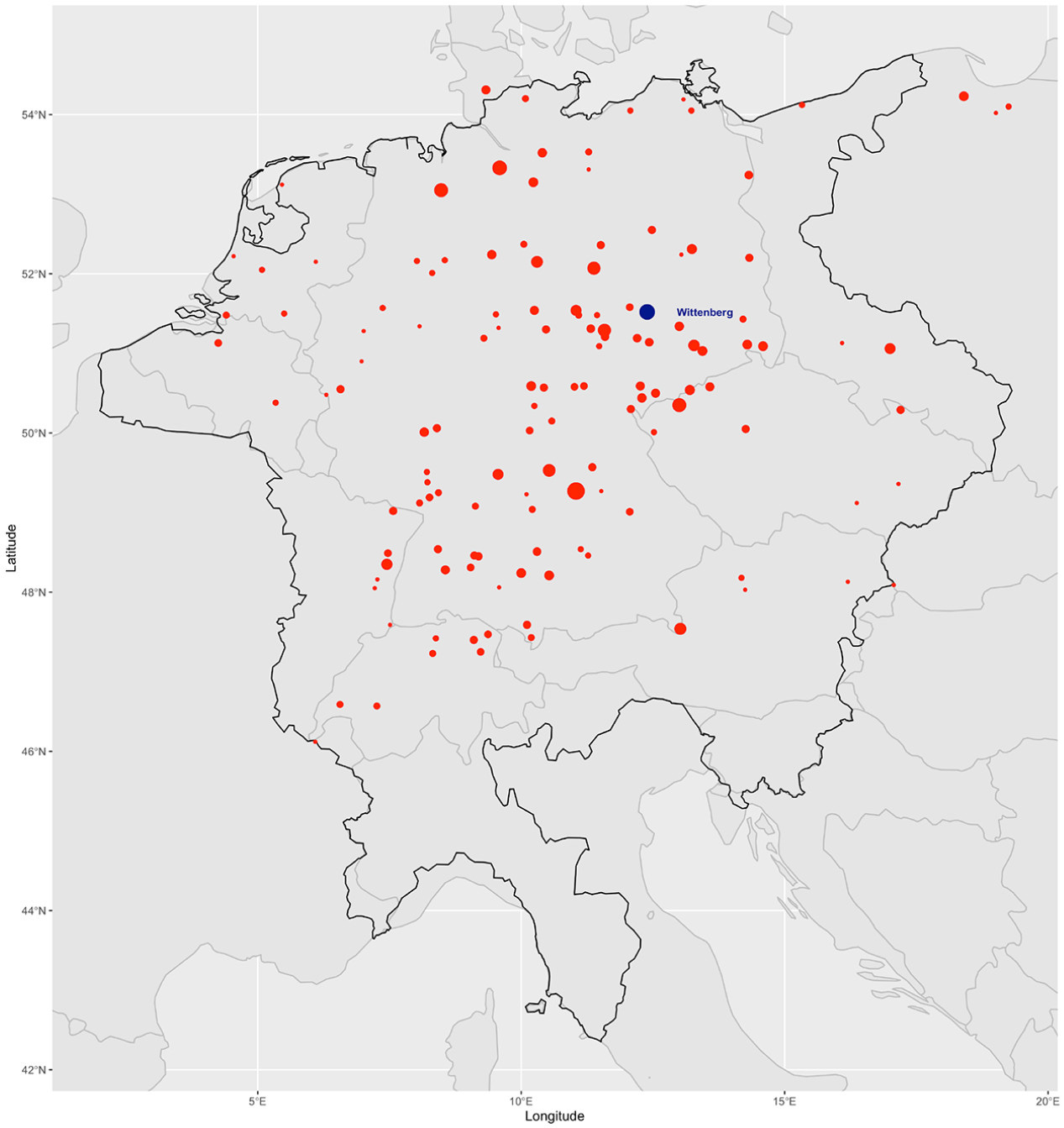

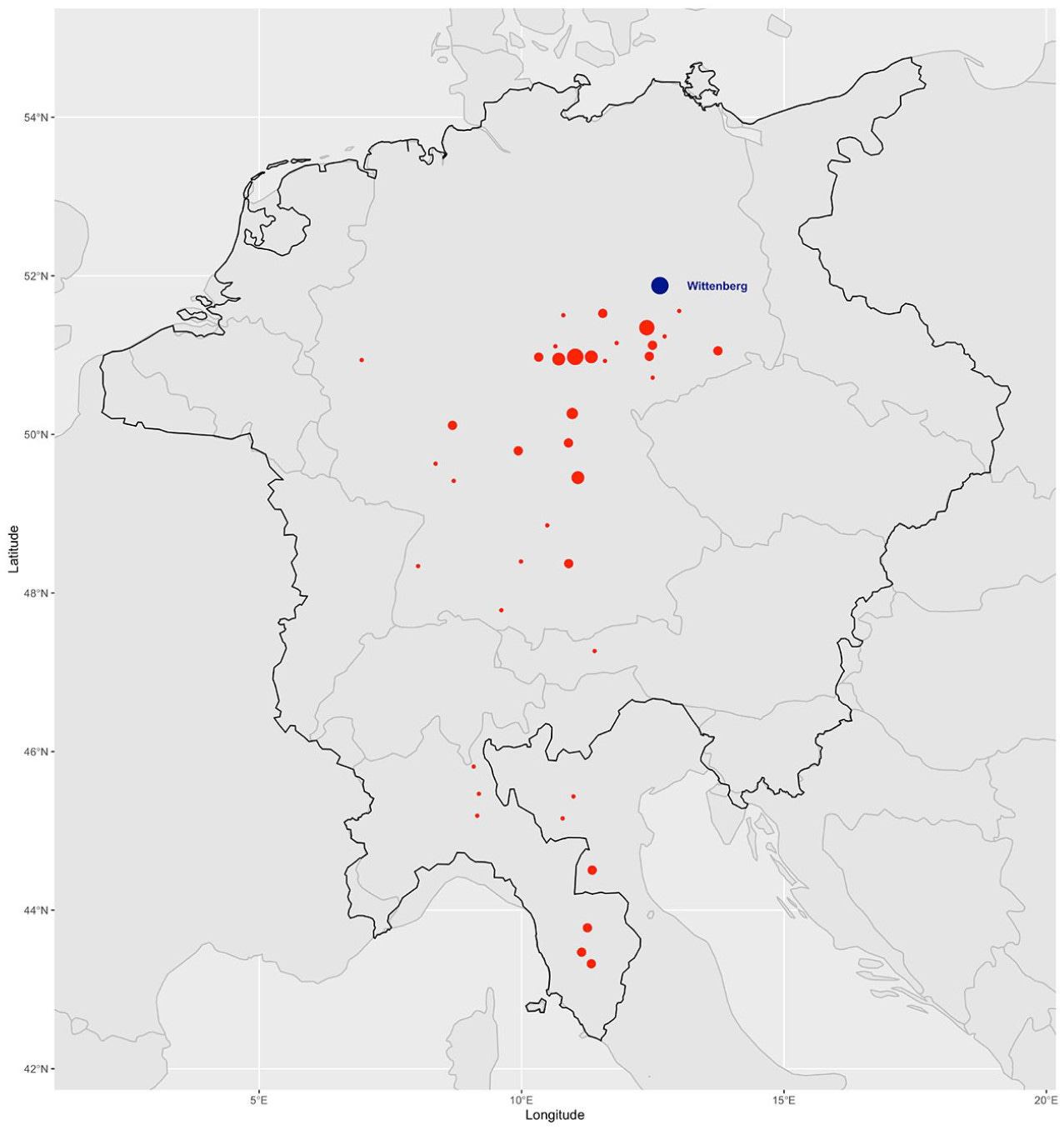

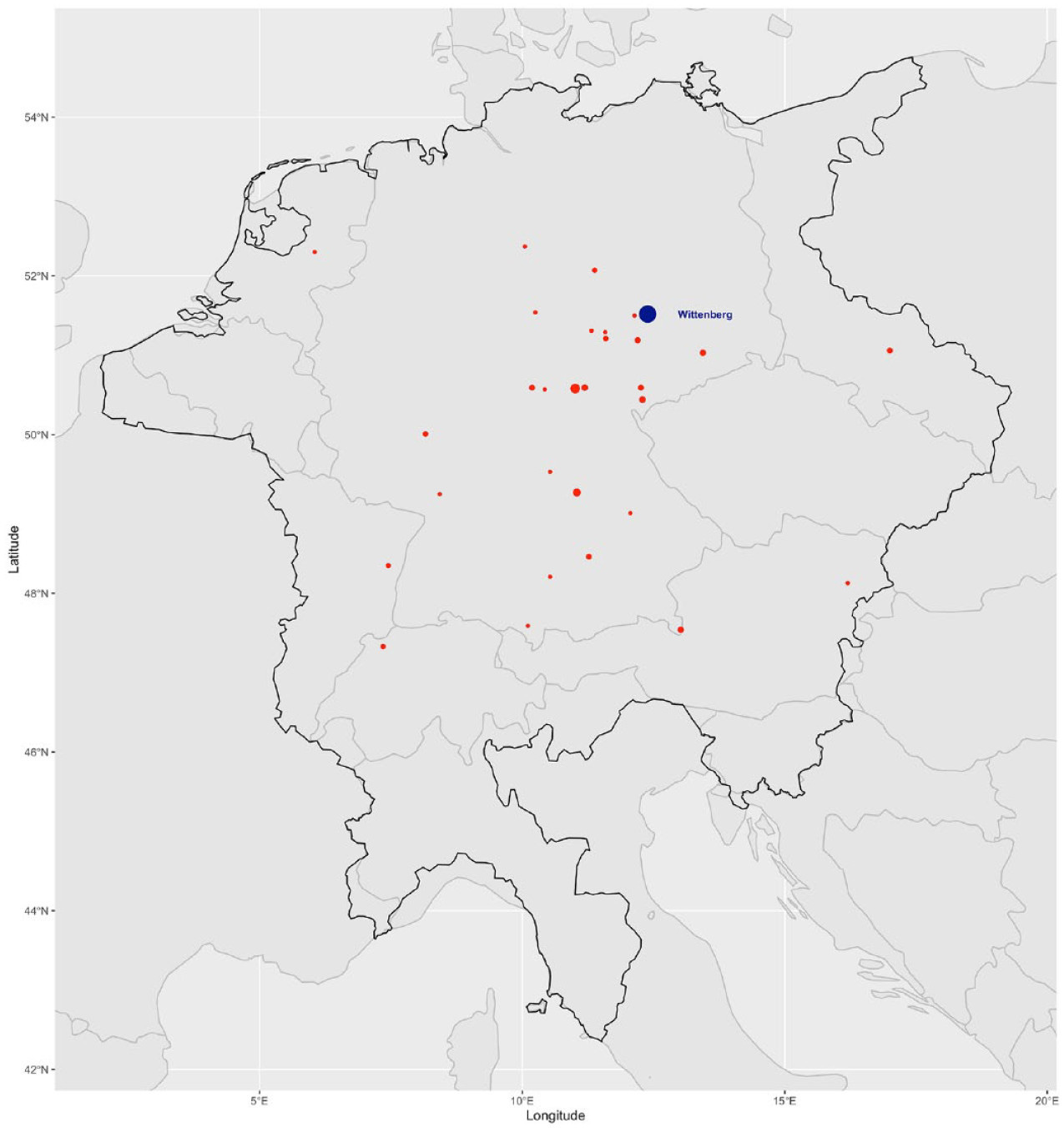

This fact was impressively documented by Becker et al. This group of sociologists took data like this, locations where Luther’s students resided:

Or places where Luther himself visited:

And even the places he just sent letters:

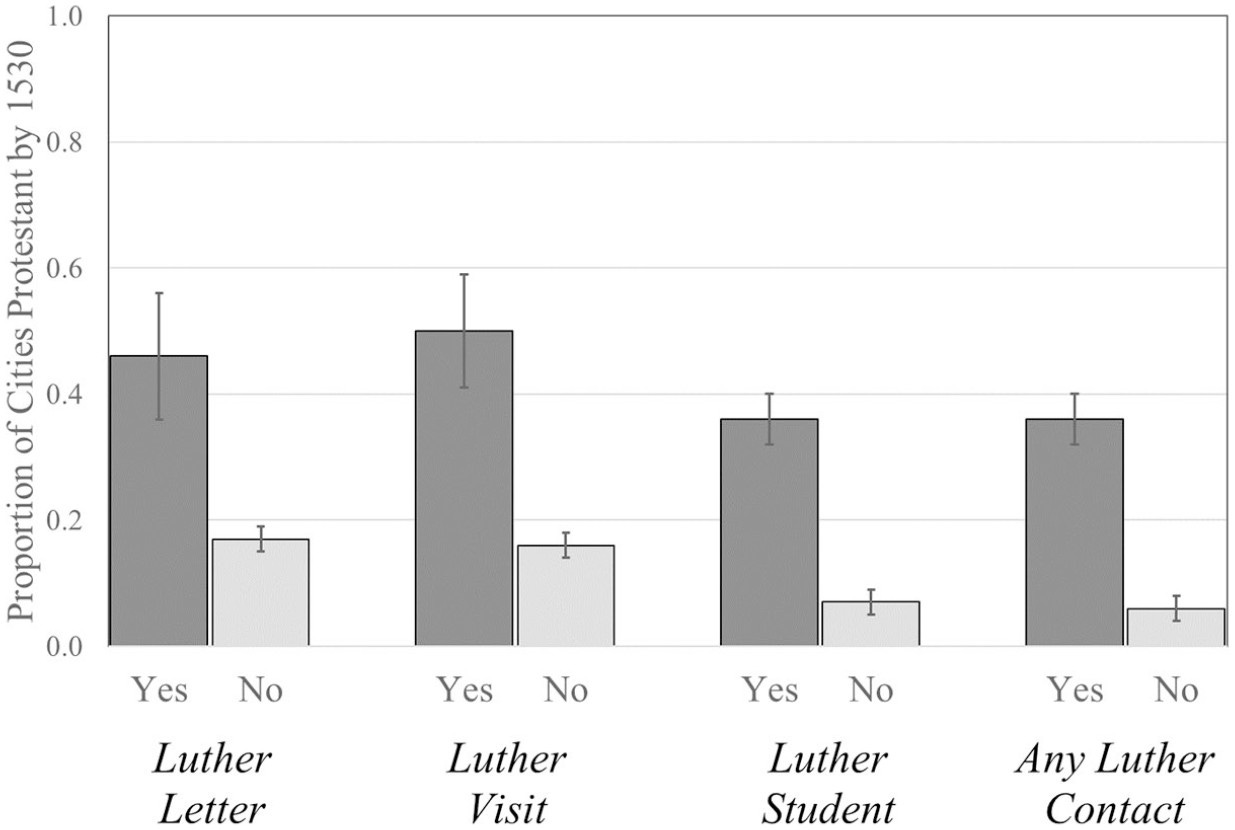

and they showed that these contacts led to greatly increased odds that those locations would adopt Protestantism:

While one might expect the places that Luther sends letters to, visits, or his students end up are selected in some fashion, that doesn’t matter at the end of the day. The fact is that Luther invented the creed that people would come to adopt, and if he hadn’t come along, either they’d have stayed the faith, or someone else would have led a movement in the same way. Either way, the world would not move without the actions of a spiritual elite.

Nevertheless, we have more details. For example, Luther’s apparent effect was robust to the inclusion of several city-level controls. But more convincingly, we have data on the road networks within the Holy Roman Empire. With this data, Becker et al. found that Luther’s effects were largely robust to controls for the connectedness of a city. Since travel was harsh, roads were poor, and trade was accordingly rare, this is meaningful, since it suggests that the diffusion of Protestant ideas through natural means alone is unlikely to explain the influence we see from Luther, because his ideas did not just take root where they were likely to as a result of geographic realities.

The authors’ simulations strengthened the case for Luther’s influence somewhat, but it’s still left open. After all, there are no means to assess the counterfactual here. But this isn’t the case for all historical examples of teaching effects. For example, a very impressive job market paper by Julius Koschnick used data on the expulsions of fellows following the English Civil War to instrument for students’ choice of college based on where they were from.

The data underlying Koschnick’s paper is highly impressive. It includes all 111,242 students and teachers at Oxford and Cambridge between 1600 and 1800. Koschnick used NLP to generate text-specific embeddings to capture similarities between texts. With this data, he leveraged students’ home locations to instrument for their exposure to particular scientists because, as it turned out, where you went to school was very non-random based on where you were from:

With this instrumental variable strategy, he found that contact with teachers led students to generate embeddings that were more similar to those teachers’ own, indicating that they worked on the topics those teachers were involved in. Because scientific revolutions require building up and exploring certain ideas, this has major importance, since it implies that changing the composition of teachers can change the direction of scientific progress through shifting students’ research trajectories. Or in other words, bad teachers mean bad ideas will be explored, wasting time and effort, but good teachers mean good ideas will be explored, making society’s efforts more worthwhile.

This idea might not sound like it needs to be said, but it does, because empirical evidence that research trajectories are sensitive to teachers’ interests means we cannot rely on progress making itself. Because it suggests that in the domain of research—which is critical for social progress—the elites who are involved in its production are sensitive to others’ interests, making sure the wrong people have less say and the right people have more can make all the difference between ending up with an English Scientific Revolution or a cargo cult.

Teacher-directed belief and activity trajectories are important even if they’re limited to affecting other elites precisely because it is elites who have outsized influences on society at large. Even though there may not be, say, large and persistent peer effects on individual politics in real-world environments, if an elite can be prompted to act out his heretical impulses in pursuit of a particular religion or to act out his desire to research on a particular research objective, this matters a lot.

If we don’t take mind of the importance of the edification of elites, we may end up like the Chinese, Muslims, or Italians.

In the Chinese case, their system of civil service examinations incentivized compliance, deference, and the observance of tradition over innovation. They created a system that could only ossify as knowledge was lost and the skeleton of knowledge-building infrastructure remained.6 The Chinese calendar may be an instructive example.

In the Muslim case, their golden age was built on the backs of ephemeral groups that failed to institutionalize their goals, leaving the Islamic world in a position where it could only slide into backwater status as a focus on religion quashed its alternatives over the generations. The failure to institutionalize scientific thinking and learnedness ensured improvements, refinements, and incremental, basic science-style progress couldn’t come about, so any attempt at an Islamic scientific revolution would always be abortive. The situation at Italian academies was similar; small groups made major advances, but did not work to create environments that would carry forward their goals, so after their members died off, the learning stopped. Worse than that, because the learning was so often embedded in people who had only limited means to put thought to word, that learning was often lost if it never made its way into a new student’s head.

This has been investigated in other areas, too. For example, Waldinger used exogenous variation in the quality of mathematics professors using expulsions by the Nazi party to show that mathematical instruction mattered for PhD student quality. In another case, Borowiecki found plausible indications that music teachers influenced music students’ skills, views of music, and the sorts of work they make. Acemoglu, He & le Maire leveraged business manager retirements and deaths in addition to estimates of role model effects on college major choice in an elaborate paper that showed that non-business managers share profits with their workers, while business managers don’t and that the difference in their values seems to be a practice induced by business education rather than selection of individuals with particular values into business education.

One of the most interesting of these papers was by Ottinger & Rosenberger. They used exogenous variation in the deployment of French troops to America, provided by logistical difficulties, to show that combatants exposed to the American Revolution went on to support the later French Revolution, while those who weren’t exposed were no more likely to show their support. The effects soldiers and officers had differed. For example, the soldiers contributed to anti-feudal revolts, while the officers did not seem to. At the same time, the officers founded political societies and the soldiers didn’t seem to. The officers significantly improved recruitment into the voluntary army, but the soldiers had no significant effect on that outcome. The most marked difference between the officers and the soldiers was the one in which they had directionally opposite effects: officer exposure led to nonsignificantly fewer expelled elite landowners, whereas exposed soldiers clearly sought to expel landowning elites. This contrast in the effects of a major exposure are important: they suggest that, at least in this instance, it may be bad to expose non-elites to revolutionary sentiment, whereas the effect on the more elite group—the officers— seemed to be good.

Martin Luther illustrated the importance of elites—and their education—not only in his time, but also nearly half a millennia later, again, in Nazi Germany.

The Nazis Again?

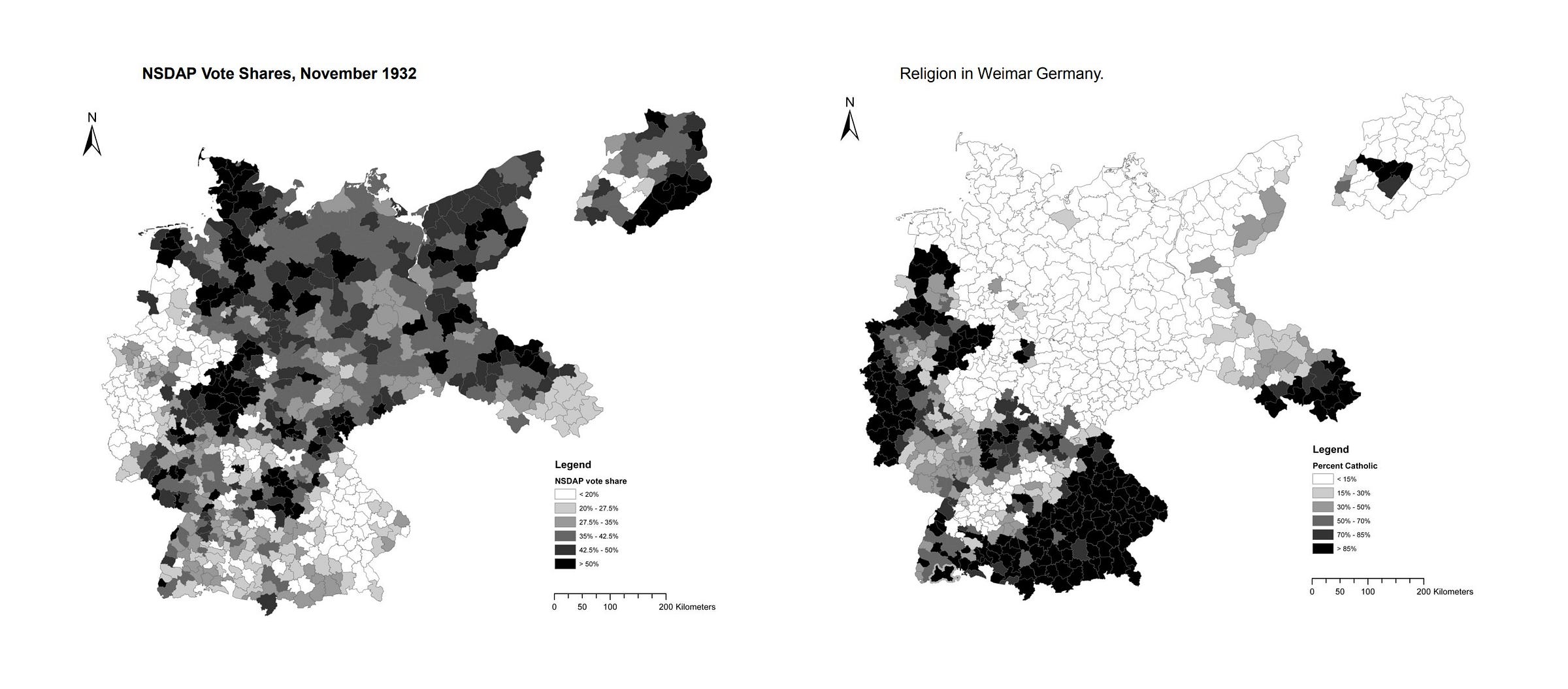

It’s well-known that the Nazis failed to win the Catholic vote. This phenomenon is so marked that if you’re not familiar, all it takes to understand it is two maps:

Some people—in my experience, mostly Catholics—attribute this to the moral rectitude of Catholics. More reasonable people attribute it to the existence of the Catholic Zentrum party, because, of course the Catholics didn’t vote Nazi, they had their own party! But this explanation is not as good as it seems.

Consider, for starters, that the Catholic church warned parishioners to avoid both communism and Nazism, but nevertheless, Catholicism had an asymmetrical effect, where support for the Nazis was reduced, but support for the communists wasn’t:

Catholics were warned against both extremes, but they only acted against the far-right, not the far-left. The truth is that the “Catholic effect” on far-right vote shares was small, at best, and Catholics only became poised against the Nazis after the church began to actively campaign against them. The efforts of the church were the determining factor here. But those efforts by the church didn’t always work. Consider this man, one Alois Hudal.

Hudal was a Catholic, but he was also a Nazi supporter, a combination that would come to be dubbed a “Brown Priest”. When the local Catholic priest was a Nazi supporter like Hudal, the difference in Nazi support between Catholics and Protestants was reduced by 32-41%! Not only that, but this support was critically timed, so they only mitigated the Catholic-Protestant difference after the church began its campaign against the Nazis:

The Catholic opposition to Nazis was not a principled matter, it was an elite thing! They didn’t support the Nazis because the church campaigned against them, and the church’s efforts could be undone by the presence of a local elite contravening the church’s orders.

All of this changed on March 28ᵗʰ, 1933, when Bishop Bertram called “general prescription and warnings of National Socialism [for Catholics] no longer necessary.” With the end of the church’s official proscription of the Nazis, the public immediately believed in" the “episcopacy’s approval of the Third Reich and its Führer”. As a result, the Catholic-Protestant difference in signing up for the party disappeared immediately:

Importantly, Nazi support has deep roots, among supporters and party members. This was shown quite convincingly in a preprint by Becker & Voth7. Their paper includes an interesting stanza from a song sung by some members of the Hitlerjugend:

We are the happy Hitler Youth;

We have no need for Christian virtue;

For Adolf Hitler is out intercessor

And our redeemer

No priest, no evil one

Can keep us

From feeling like Hitler’s children.

Not Christ do we follow, but Horst Wessel!

Away with incense and holy water pots …

This verse has obvious religious significance. Though it sounds clichéd, it supports the idea that the Nazi movement was a religious one. Or, at least, quasi-religious.

Among the Nazis’ propaganda efforts was an movement to gather Germans’ essays about their views on the Nazi party for dissemination. The essays are, in many cases, deranged, but they are, overall, incredibly highly religious. This one that Becker & Voth presented, from Anges Mosler-Sturm of Berlin-Spandau, is representative:

a revelation illuminated us—he [Hitler] is the Germany’s savior! […] civil war broke out, everything high and holy was trampled into the mud by the animalistic, Jewish-Marxist,… masses. With […] most holy indignation we fight for Hitler and his idea […] a single scream of redemption: Adolf Hitler is chancellor […] new hope, new faith, new power emerges from the German people like an enormous stream […] a great, good, and strong people stand up courageously, to follow its only god-given Führer and savior—Adolf Hitler…

The quasi-religious nature of Nazi support is obvious. The opposition to Nazism from Christianity is also obvious, but not all Christians have the deep beliefs whose bearers would end up opposing Nazism. For many, their beliefs were so shallow that Nazism could easily replace them. Recall the words of C.S. Lewis:

Where men are forbidden to honour a king they honour millionaires, athletes, or film-stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.

One way to represent the strength of belief in Christianity is by looking at how often people give their children Christian names. In the least Nazi-supporting parts of Germany, that happened often. Another way is to look at how much people believe in clairvoyance, a decidedly un-Christian belief. If we’re talking about the religiosity of an area, those places that produced notable men of faith should also be more deeply Christian given persistent elite effects. Becker & Voth charted each of these things:

For a clearer picture, when these things are combined into an index of the shallowness of an area’s Christian beliefs, that looks like this:

Christian names appear as a particularly strong indicator of the strength of Christian belief. Using that, Becker & Voth showed that, among Nazi party members, Christian names were less common. This between-areas phenomenon was also a between-individuals one:

The deep roots of Nazism appear when their instrumental variable strategy comes into play. They used the distance to pagan worship sites and the distance to medieval monasteries to predict shallow Christian beliefs, finding that, in both cases, they operate as expected: people closer to pagan sites were shallower Christians, and people closer to monasteries were more strongly Christian.

With these two papers, we now have a story: for reasons of historical contingency, some people have weaker Christian beliefs than others. These people were more likely to adopt Protestantism, but differences in the shallowness of one’s Christianity are also present among Catholics. The people with strong beliefs were naturally insulated against Nazism, as it went against their creed. But for many others, their shallow beliefs were easily replaced by Nazism when it came along. Catholics were not especially pious or righteous, they were simply buoyed against the Nazis because they had coordinated elites who stood in opposition to them. When those elites failed to stand against the Nazis, the shallowness of parishioners’ beliefs revealed itself, and they too joined up with the Nazi party.

Elite coordination within institutions is necessary for ‘elite cultures’ to survive, whether religious or scientific. This is why Protestants were so much more vulnerable to the Nazis than their Catholic peers: as smaller, less centralized religions, they had weaker elite networks, and an accordingly more limited ability to combat the new, totalitarian state religion that Nazism represented.

Nazism had major, pernicious impacts on world affairs, but, I’ll contend, because of the high human capital of Ashkenazi Jews, its most important impact on research productivity was from the Holocaust.

(Ashkenazi) Jews!

Everyone knows Jews are a high-achieving group. All you have to do to see that is to read pieces like this Tablet Mag article lamenting the decline of Jewish influence. In the process of describing a decline, the article necessarily also describes a peak and a still-impressive current state.

Due to their high achievement, the presence of Jews is a demographic dividend for the nations they reside in. Consider Nazi Germany. When the Nazis came into power, they dismissed scientists who were Jewish or “politically unreliable”. Waldinger documented that the dismissal of these scientists had major, persistent negative impacts on the number of scientific publications produced by affected departments. But by contrast, the effects of literally bombing those departments and destroying their physical capital alone were small and transient.

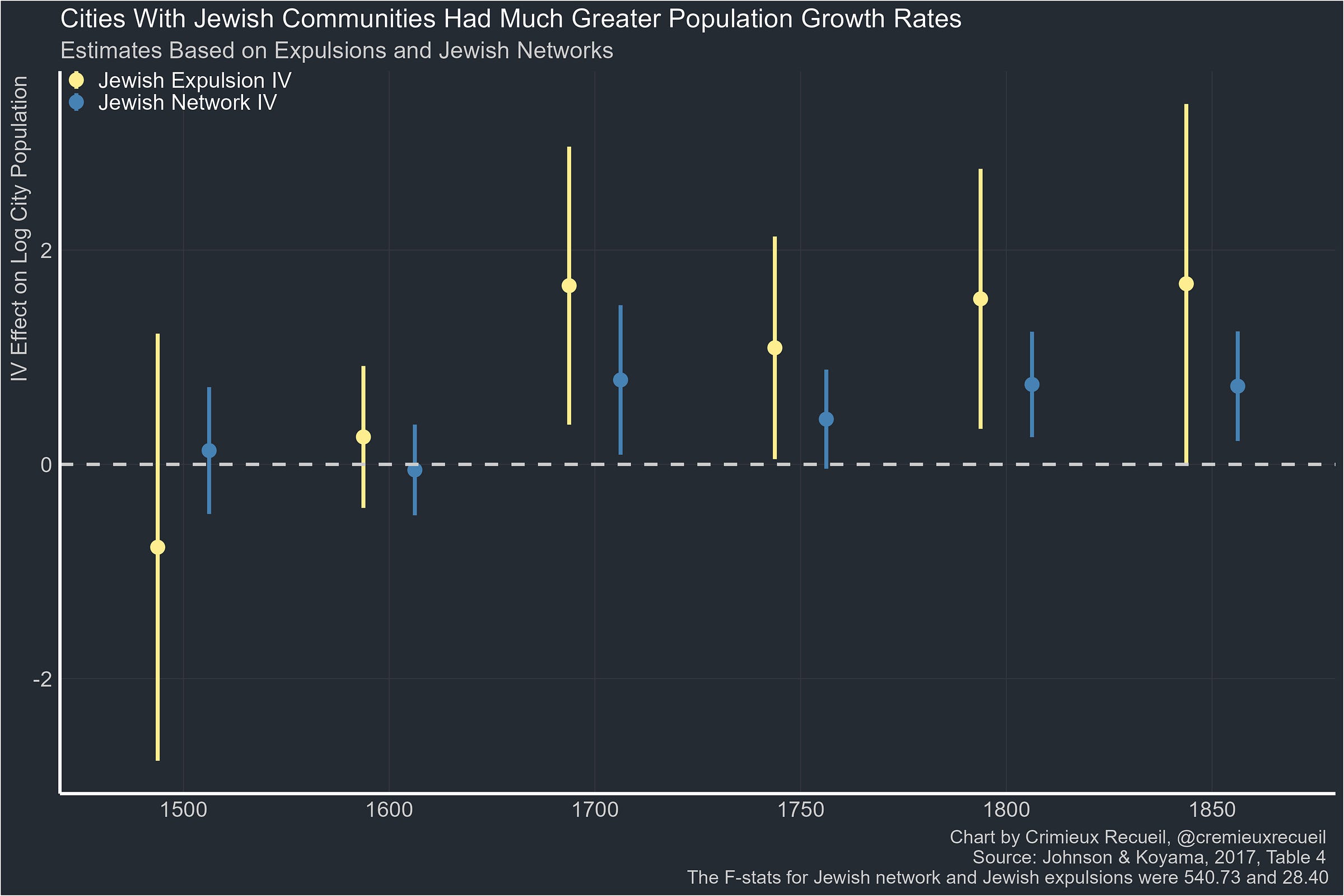

But was this always the case? One way to see this is to look directly at the Jewish demographic effect—in other words, how Jews affect population growth. As it turns out, Jewish communities have not always been beneficial in this respect. In a brilliant paper, Johnson & Koyama instead recorded this:

In the period 1500-1850, Jews didn’t seem to be beneficial (or harmful) prior to 1700. To understand why, we have to understand more about recent Jewish history.

First thing’s first, we should begin with the Sephardim. This group of Jews was expelled from Spain in 1492 following the issuance of the Alhambra Decree. from there, they traveled to Israel, the Ottoman empire, the Papal States, the Maghreb and Egypt, the Netherlands, England, Wales, Lithuania, Germany, France, Austria, Silesia, Crimea, and more destinations. The expulsion of these “Spanish Jews” led to the creation of a tightly-interconnected long-distance network that fostered trade between the places they ended up, like Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Livorno, and London.

The second thing we need to understand is the Hebrew Press. Just fourteen years after Gutenberg’s 1455 invention of the printing press, a Pentateuch commentary was printed in Rome. Due to their highly literate culture, Jews were among the first and most willing to embrace the practice of printing. Incidentally, this interacts with the presence of Sephardim in an area, because Sephardim picked up printing in 1476, and sixteen years later, they took their presses with them on their voyages throughout Europe. Hebrew Presses ended up in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and even the Ottoman empire as a result.

The third thing to understand are Port Jews. Port Jews are very simple to explain: they were Jews who lived in port cities. These cities often recognized that Jews had major utility for facilitating trade and commerce, so they tended to afford them extensive religious freedoms. This recognition of the value of Jews for commerce has also led, historically, to numerous instances where rulers have tried to welcome Jews into their realms. For instance, Frederick the Great tried to settle Jews on his borders in hopes that they would act as trade promoters. The utility of Port Jews is obvious.

So with these things in mind, do they explain the Jewish demographic dividend? The answer seems to be no. In the whole period 1500-1850, Sephardim were positively related to city growth, but in the period 1750-1850, they were negatively related to it. Moreover, the Hebrew Press was only ever marginally related, but in the wrong direction, too, and Port Jews just never seemed to matter for growth at all.

So with these factors out of the way, we’re left wondering about the answer. But we do have it. The reason cities’ Jewish populations began to be associated with their growth is because of emancipation, the era in which Jews gained equal rights with their non-Jewish peers.

Emancipation kicked off in the 17ᵗʰ century in two major places: Britain and the Netherlands. After 1654, Jews were free to live throughout England, and the limitation of Jewish life to moneylending pursuits in the Dutch Republic came to an end. By 1700, those places’ Jews had become free. But progress still had to be made elsewhere, and the Enlightenment was a likely source.

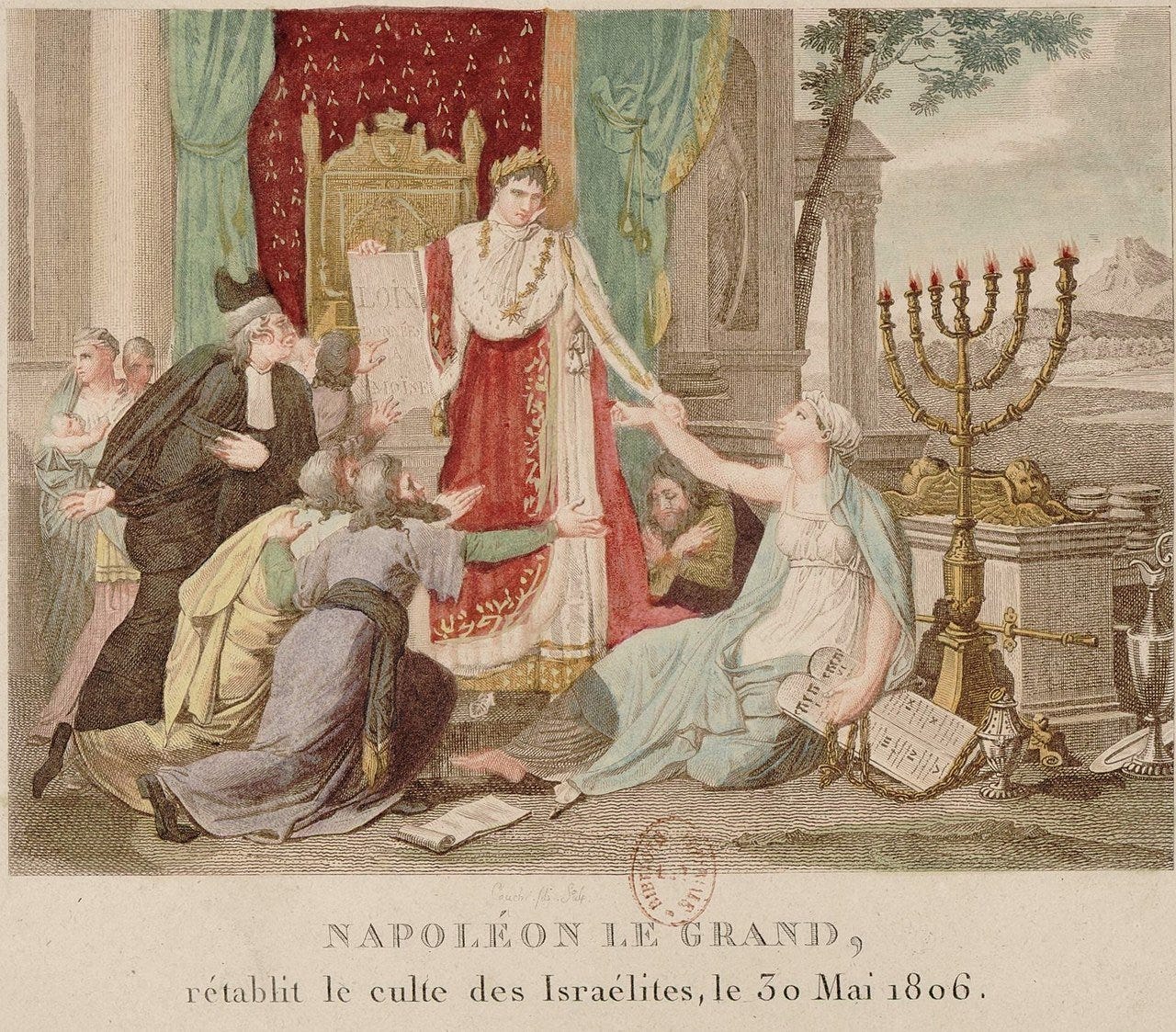

In 1782, Holy Roman emperor Joseph II laid out the Edict of Tolerance, giving freedom to many religious minorities throughout his lands. This didn’t provide full equality with Catholics, but it was a major step in that direction. The biggest change came through the provision of formal equality to Jews in France in 1791. The revolutionary zeal that sprang forth a few years prior had brought about a lust for equality, and naturally, a Jewish countryman was to be considered no less a countryman because of his heritage and faith, which is why pictures of Napoleon adorn the homes of so many Jews.

Napoleon was regarded by Jews as the great emancipator. Where he went, he brought emancipation with him. As he was pushed back, many places reimposed their restrictions. But freedom, once felt, can not long be denied, so Prussia gave Jews rights in 1812, Denmark gave them rights in 1814, and so on, until even places like Poland had to recognize Jews’ rights.8 After Germany’s unification, those rights would follow throughout the realm.

To understand why this matters, understand what it means: for the first time, Jews were full members of the marketplace. Before this point in time, Jewish reproduction was slant towards scholarship and success in the domains they were allowed to inhabit. The most scholarly Jews were substantially more fertile than their peers, and those who couldn’t pass muster left the faith. As a result, Europe’s Jews were like a kettle getting ready to boil over. When emancipation finally occurred, boil over it did: a population with extraordinarily high human capital entered the world en masse and the effect was nothing short of enormous:

Cities with larger Jewish populations grew much faster than those without them, but only once Jews were free to work. Before that, Jews, of course, couldn’t make their mark on city growth to the same extent. How could they? They were plenty smart, but unless they’re working, those smarts go to waste. Freedom changed the situation, allowing everyone to benefit from what was likely the most sudden and impactful blossoming forth of human capital in the history of mankind. Nowhere else has an extremely gifted and persecuted population been freed like this, and we’re all lucky that it happened.

But disproportionate Jewish influence isn’t only an early modern phenomenon. It’s major in the modern day, and depending on your own politics, you might consider that to be a good thing.

In a study from the late-1980s, Lerner, Nagai & Rothman recorded something curious: America’s elites weren’t very ideologically divided from wider society. Or this would be true, if Jews weren’t included in the sample. This split is very cleanly visible:

The non-Jewish public leaned somewhat conservative. To be sure, members of the Jewish public also leaned more conservative than Jewish elites, but they were substantially less conservative than society as a whole. When it came to elites, the typical non-Jewish elite still leaned somewhat conservative. The split among non-Jews was only 17 points in net conservatism, but among Jews, it was an incredible 48-point split.

Because of the disproportionate influence of Jews in politics, media, and academia, this means a lot. Richard Lynn’s The Chosen People includes some quantification to this effect. For example, he noted on pages 308-9 that Jews constituted 26% of the “media elite” (as recorded in The Left, the Right and the Jews) in 1975. In a study published by Forbes in 1982, Jews were found to be 30% of the media elite, 66% of Hollywood movie stars, and 46% of Hollywood TV stars. In a Vanity Fair article published in 1994, the “new establishment” was found to be 48% Jewish. Similar statistics apply to groups like Nobel laureates, law school faculty, sociology professors, economists, physicists, political scientists, historians, philosophers, mathematicians, top intellectuals, social scientists, and humanities academics, and so on for virtually every category of elite. The corresponding influence of Jewish elites in the political realm can be inferred from these statistics.

Jews have been welcomed and they’ve also been expelled, time and again, by various groups, in part because of their disproportionate influence. But they’re not alone in this. Other highly-successful groups have also faced persecution.

Huguenots

Immigrants affect everything, from politics to technological progress, and they are more capable of eliciting these changes when they are skilled. As noted based on the Jewish experience, rulers were aware of this fact. Joel Mokyr provided several more examples in The Lever of Riches. In that book, he documented how European rulers sought to facilitate the diffusion of technologies through attracting skilled foreign laborers. Other scholars have agreed that this was common in the early modern period, and also, that host countries benefitted from these efforts, so rulers were not acting against interest.

It is generally agreed that one of the clearest examples of rulers trying to facilitate the diffusion of technology has to do with Calvinists. The Calvinist Huguenots have received an enormous amount of attention after their exodus from France and their resettlement in the German state of Brandenburg-Prussia. This event is actually a wonderful example of both push and pull factors in migration, as religious persecution in France pushed Huguenots to leave, while the Edict of Potsdam pulled them to Prussia by offering them religious freedom and settlement opportunities. Because the barriers to migration were reduced, the barriers to transmitting any technologies the Huguenots might have been familiar with were also reduced. An additional factor contributing to Huguenot migrations from France to Germany was that Germany in the late-17ᵗʰ century was technologically backwards, giving the Huguenots a niche to ply their knowledge in their new home.

The Huguenots who fled to neighboring England and the Netherlands were well-to-do, whereas the Huguenots who ended up in Brandenburg were poor on arrival due to the hardships they faced, but they were nevertheless representative of the whole of the society they came from, albeit the urbanized part of it. Wilke’s Zur Geschichte der französischen Kolonie included estimates that Huguenots who arrived to Prussia were 5% noblemen, 7% mid-level functionaries, 8% trade and manufacturing bourgeoisie, 20% workers and apprentices, 15% farmers, and 45% small artisans and craftsmen. At all levels, Huguenots were well-educated, in part because their creed demanded Bible reading, and also because it encouraged people to embrace a hardy Protestant work ethic, while the penalties applied to them encouraged people to leave the faith and to avoid joining it in the first place unless they could bear them. The arrivals were even better educated than Huguenots as a whole, because Frederick William’s welcome changed from being open to all of them prior to 1686 to denying the entry of the unskilled thereafter.

Thus, Prussia acquired a foreign elite.

Prussia had good reason to welcome the Huguenots like they did, too. For one, Frederick William rose to power in 1640, some eight years before the close of the Thirty Years’ War. This war brought about major population devastation directly and through reintroducing the Black Death, leaving the country majorly depopulated. Frederick William and his successors acknowledged this problem and sought to remedy it through the Peuplierung—a repopulation policy where births and migration were encouraged. This policy was a success, but it would take time. In fact, a full recovery to pre-war levels would only happen long after Frederick’s death, some time in the middle of the eighteenth century.

On arrival, Huguenots had certain expectations placed on them. Firstly, they were expected to eventually, but not immediately, become taxpayers. Secondly, they were expected to use their knowledge and skills to set up and to supervise factories so that Prussia could produce the “domestic” goods that it presently had to import. The Prussians were under the influence of mercantilist economic doctrines, so they believed these immigrants would benefit them if they contributed to a positive balance of trade. Accordingly, this act of religious tolerance was also an active part of Prussian economic policy.

With the Edict of Potsdam that Frederick William passed right after the Sun King revoked the Edict of Nantes, Frederick gave the Huguenots safety and the ability to take any abandoned houses and lands they found, whilst also enjoying tariff exemptions and exemptions from taxes and other impositions excluding the one on consumption, for some fifteen years. The Huguenots were also not subject to guild coercion for ten (later fifteen) years, and if they wished to contribute to setting up factories, they were provided loans to do so.

Some 25.7% of the Huguenot craftsmen who arrived in Prussia were occupied producing cloth, and 32% were involved in the production of other textiles. In other words, over half were involved in the textile trade that stands as most people’s go-to example of early industrial progress. Because of these skills, this group revolutionized production in Prussia. In fact, because they brought in knowledge that centralized manufacturing and added more hierarchy to work organization, they were effectively the bedrock of Prussia’s division of labor, allowing them to jumpstart their way into the industrial revolution.

In fewer words, the Edict of Nantes built Germany. As Frederich List put it in his 1841 The National System of Political Economy, “Germany owes her first progress in manufactures to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and to the numerous refugees driven by that insane measure into almost every part of Germany.” France threw away an early lead in several industries and gave it away to the Netherlands, England, and Prussia.

But we don’t need to rely on historians; we have quantitative evidence of Huguenots’ effects. Hornung has produced what is the go-to paper on the impacts of these immigrants. One need only look at his charts to see how Prussian textile manufacturing in 1802 and Huguenot colonies (founded post-1685) overlapped.

Quantitatively, the effects on manufacturing output were large and significant.

This effect also held up to a variety of checks, including assessing impacts on non-relevant industries and the use of alternative measures of Huguenot influence, including a “horse race” control that showed that it was the first generation of Huguenots who had their unique influence on technological diffusion, as you might expect when a technology is diffused from some population immediately rather than over generations. Furthermore, this effect showed up in instrumental variable analyses, in which the share of population losses during the Thirty Years’ War was the instrument. This is clever, because the Peuplierung meant allocating and the Edict of Potsdam meant encouraging Huguenots to go to places that were depopulated.

The Huguenots encouraged agglomeration in Prussia, leading to more large firms, specialization in textiles, wool, linens, cottons, and silk, and effects specific to what they knew, which was not non-textile industry, leather, metal, tobacco, or mills, but which did also include soap. Through this evidence and more, Hornung showed with high certainty that this elite-biased migration led to technological diffusion in a way that greatly benefitted Prussian development, and these immigrants’ impacts were felt for many generations.

Many influential migrations happen from abroad, like with the Huguenots, but in other cases, they’re more internal.9

The Fall of the Norf

In many countries, the north is more successful than the south. This often has to do with socioeconomic status, matters of historical contingency favoring the north, and it also often ends up showing up in measured smarts. For example, northern Italians are more intelligent than southern Italians, even when they migrate within Italy. But England is different: in England, the north is a failure, and we probably know why.

In a wonderful paper by Clark & Cummins, they documented major and selective migration out of the north of England, towards its south—the Great British Brain Drain. Over time, this phenomenon has led to divergences in quantities like gross value-added per person, life expectancy at birth, Oxbridge attendance, home values, and public sector employment rates, all of which favor the South-East over northern England and Wales. This is clearly visible in the statistics on output per person, where the South-East has taken off ahead of the other regions:

Likewise, we see something curious when we look at probate rates by region of death: they’re clearly less common in the north!

At the same time, probate rates by the region of one’s ancestry do not differ. This suggests that whatever leads the north to lag does not lead northerners dispersed throughout the rest of England to lag.

When this sorting was much stronger than today, we see that probate rates dramatically varied between northerners who stayed in the north and the ones who went south. In fact, the southerners who went north were more like the northerners who stayed in the north than the northerners who sent south:

This difference in similarity was even more true when it came to mean wealth at death:

The implication of status symmetry between northerners and southerners in the same regions suggests something else worth noting: northerners don’t suffer disadvantages in the English economy. They don’t perform poorly because of, say, discrimination by place of origin, northern ancestry, etc. But more importantly, they also don’t perform poorly because of a locational disadvantage unique to the north. The extent of the northern disadvantage is so minimal, that, it’s equivalent to just a single point on a 0-100 scale for occupational status.

The exodus of skill from the north implied by these statistics (in addition to the movement of low-skill southerners going north) is pretty major. Clark & Cummins placed this in different terms to make the point more explicit: as the high-skilled filtered out of the north, surnames associated with the north, with and without a history of Oxbridge attendance, were now being born elsewhere increasingly often, and this was more true for the most elite surnames than for the least or the moderately elite.

There’s more data in the paper, but I believe this summarizes it well enough:

Holders of surnames concentrated in the North in the early nineteenth century were not disadvantaged in recent years in terms of education, occupation, political power, or wealth compared to the holders of surnames concentrated in the South. Since the holders of such ancestral Northern surnames are even now disproportionately located in the North, any geographic disadvantage of that area would have reduced the average social status of Northern surnames. Further holders of Northern surnames dying in the South were wealthier than holders of Southern surnames dying in the South. And there is sign that migration to the North was that of less advantaged Southerners. Holders of Southern surnames dying in the North were poorer that Northern surname holders dying in the North. These Northern surnames dying in the North were an adversely selected group, so the Southern migrants must also be adversely selected. When we look at surnames that ancestrally are of Scottish or Irish origin we find again that holders of the surnames located in the North are an adversely selected group. Their house values in the North are at or below those of the adversely selected native English population there. But in the South their house values exceed those of the positively selected native population. Thus the pattern of external migration into England has also contributed to regional disparities.

The reasons could be economic—the south may have better opportunities for high-skilled labor and the north might have better opportunities for low-skilled labor, like in coal mines—but it might also be amenity-based—the south is warmer and it has cultural amenities that middle- and upper-class families enjoy. Whatever the reason, there’s clear evidence that the failings of northern England are attributable to historical migrations. This perspective is supported in other ways, too.

In a brilliant paper by Abdellaoui et al., it was shown that educational polygenic scores—whose efforts are substantially, but not wholly causal—are affected by sorting. In other words we have positive evidence that the genetics underlying status attainment were regionally stratified thanks to migration. This is very visible when comparing coal regions with non-coal regions.

In panel a, we see that polygenic scores for educational attainment in general are down across the board.10 In panel b, we see that people have been filtering out of coal regions, and doing so in a way that’s likely selective. In panel c, we see evidence for this position: moving away from the coal fields is selective with respect to status genetics.

This finding recently replicated in Estonia,11 where it was shown that migration in Estonia intensified regional differences, and also amplified the effects of polygenic scores like it has in Britain. This sort of finding really ought to be the default hypothesis. After all, phenotypes reflect genotypes in realistic scenarios, so when there’s skill-biased migration, we can be reasonably sure that it’s also biased with respect to the genetics underlying observed skills.

If we take this for granted, it puts a new face on migration-related findings like

The mass migration of tyender—servants—from Denmark between 1868 and 1908 resulted in the regions they left being wealthier today.12

The descendants of Germans who migrated from central Europe to the areas of modern-day Hungary, Serbia, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia have supplemented the human capital in those places, because they brought higher numeracy skills with them. Moreover, because they were not selected among Germans, this also suggests that, in general, Germans have higher human capital than Eastern Europeans.

The late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century arrival (1888-1920) arrival of German, Japanese, and Italian migrants in Brazil supplemented their human capital, as their presence in an area in 1920 predicts current human capital. The same is not true of the more basal population of Portuguese and Spanish, even though, for example, Portuguese and Spanish migrants were positively-selected. Score differences across Brazilian regions and races are also still present, but the same is not true in Puerto Rico, presumably because of how intermarriage patterns differ between these places.

America has tended to receive far more inventor immigrants than the number of inventor emigrants it produces. A finding that feels related is that America receives lots of Indian Institute of Technology graduates as immigrants. In fact, the better graduates did on the Joint Entrance Exam, the more likely they were to leave India in general, with 360 of the top 1,000 leaving, 62 of the top 100 leaving, and 9 of the top 10 leaving. Overall, 65% of these migrants went to the United States.

During the 1870-1910 African American migration, the migrants who left were more literate and healthier than those who stayed behind, a finding that replicated with later cohorts. This finding is selective in a few other ways. For example, Great Migration migrants increased murder and incarceration rates in their destinations, and at the same time, those who left the American south were less African in ancestry than those who stayed behind, but they were also more African than the Blacks who were already in the north.

Arrivals to America showed declining skill over time, and return migration from America was also negatively selective, such that migrants with lower skills were more likely to leave America. The first effect made America’s received migrants less skilled over time, but the latter left America with higher skilled migrants. In total, America’s migration was likely to be at least somewhat selective with respect to origin countries.

One particularly interesting example regards Scandinavian migrants to the U.S. Knudsen found that those who left Scandinavia behind were more individualistic than those who stayed, leading to permanent decreases in individualism in the sending countries. As Gwern has documented, Knudsen’s cultural attribution of this effect may be hasty, because what she observed was also consistent with a genetic explanation: with realistic heritabilities and truncation, the expected effect on individualism is about what Knudsen observed.

Whatever the reason, migration matters, receiving or taking. To show this more clearly, let’s bring this back to the American south which, in some form or another, is going to rise again.

The South Rose Again, Sort Of

In a stunning paper Bazzi et al. documented that post-Confederate Southern White migrants made the places they went to outside of the south more conservative. This was so interesting that it was covered by The Economist. The impacts are highly-visible. For example, each percentage point increase in the share of a district that was occupied by southern-born Whites in 1940 was associated with the following effects:

More generally, southern Whites just increase the support Republicans receive:

In effect, southern Whites’ mass migration from the south managed to blur the lines between regions politically. A substantial part of America’s cultural and economic conservativism is linked to this migration—no wonder they covered it!

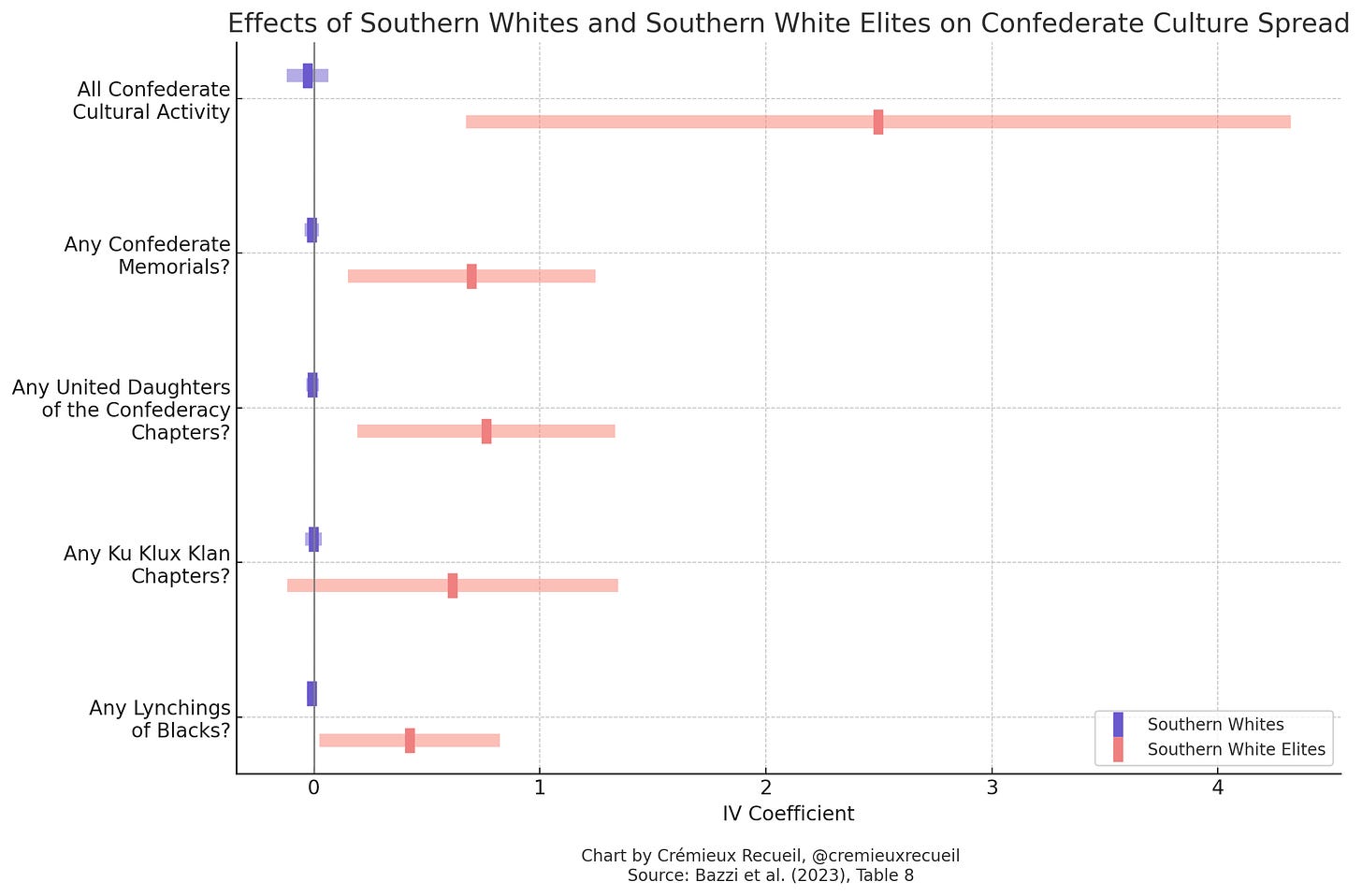

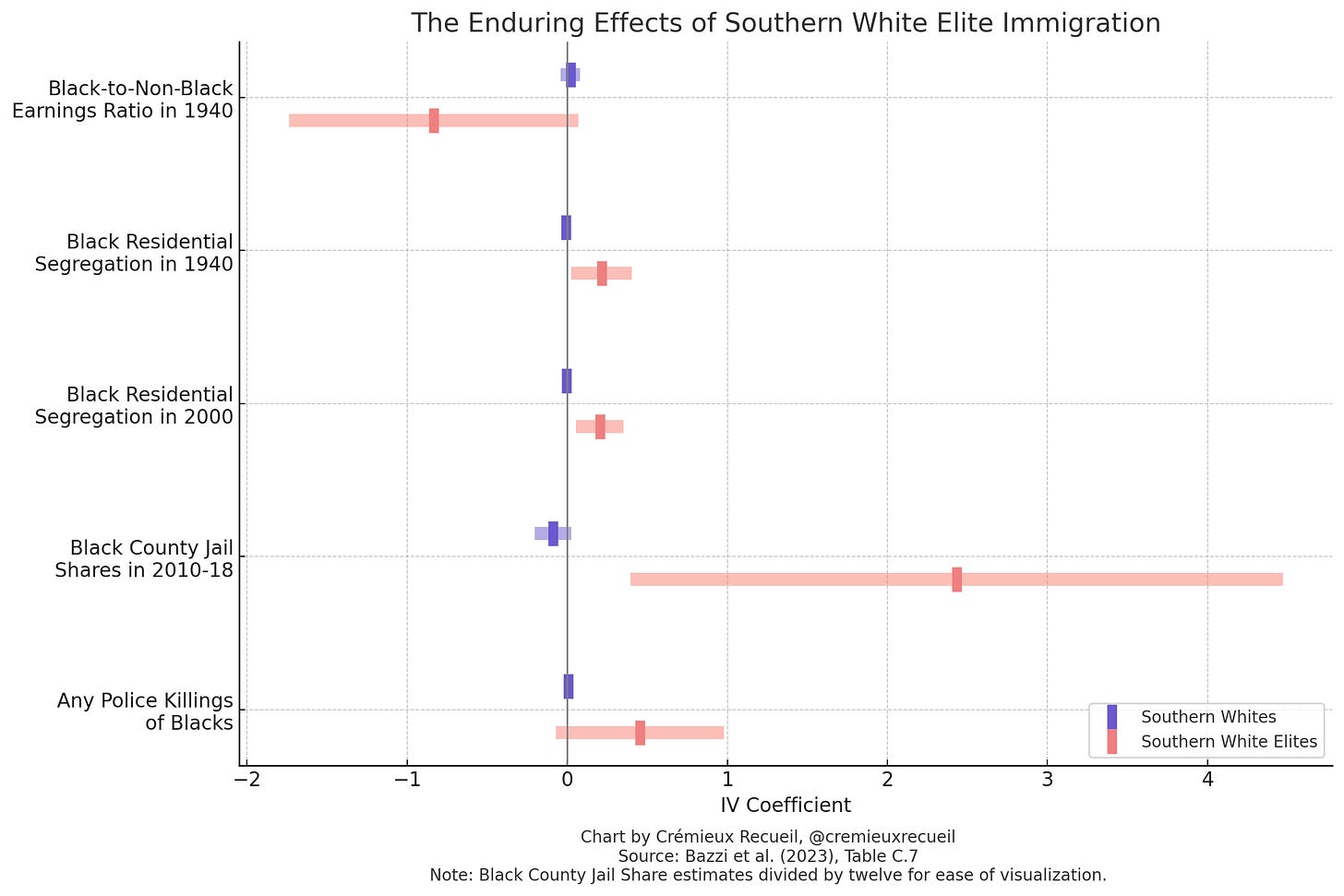

But Bazzi et al. didn’t stop there. Even more recently, they’ve brought forward a preprint showing that the spread of southern culture across the U.S. that came with southern migrants was not due to southern Whites in general. No, instead, it was attributable to southern White former slaveholders: the prototypical planter elite.

In terms of cultural impacts, the effects that we might ascribe to southern Whites in general are entirely attributable to the elites. So, where southern Whites went, it is not proper to say they brought Confederate culture. It would be more accurate to say that Confederate culture accompanied the elites.

Using a different set of outcomes, results are more ambiguous, but they are nevertheless directionally consistent with enduring impacts of the migration of southern White elites.

This all makes sense. It fits with the rest of the thesis. The people who matter for outcomes are generally not the everymen except insofar as elites leverage them for, say, votes and mobs. It’s elites that determine the direction of world events, and this is no less true in the southern example.

Regarding how these elites did it, the first thing to note is that losing their wealth in slaves did not eliminate their elite status. In fact, their sons regained most of this lost socioeconomic status within a generation, and their grandsons entirely recovered it. The second thing to note is that the finding that they maintained their status is affirmed in this data, too: former slaveholders were able to disproportionately obtain positions of authority, to become lawyers, judges, and public administrators, but not to enter lower-status, less influential occupations, like law enforcement, religious work, or educating. The former slaveholder sample ended up with higher occupational income scores and much lower odds of working in agriculture.

Eliteness is sticky, and the persistence of Confederate culture and southern preference realization in policy is an elite-led phenomenon.

The Circulation of Elites

Eliteness is persistent within lineages, but elites are not static. As Vilfredo Pareto documented, elite positions in society are continuously emptied and filled with other elites, hence the circulation of elites. Another way to express this is as the iron law that holds that all elite changes are due to the actions of another elite.

Today, we live in a world where our elites are rotten. Borrowing a quote from James Lee:

[The] abilities posited to underlie the attainment of status are just that—abilities useful in getting to the top. There is no implication that the mix of relevant characteristics includes virtue, which even in ancient times (aretḗ) was recognized as distinct from mere status. When we examine what the people at the top have wrought in our country today, we see clear signs of their inadequacies. We need a new elite. Let us hope that the surprisingly lawlike behavior of movement in and out of elite status that [Gregory] Clark [has] reveal[ed] does not preclude a badly needed renewal.

A well-known example of a tool that promoted elite circulation was the SAT. By allowing qualified non-WASPs to compete and earn elite educations, the SAT reshuffled America’s elite and effectively ended the long era of WASP domination. In line with the latter part of Lee’s quote, at the same time, the SAT revealed that people who come from humble means rarely have what it takes to fill a society’s elite roles. Standardized tests promote mobility for the deserving, but they also reveal that most people are already appropriately positioned and elites tend to enjoy their positions thanks to their abilities. We can see this with wealth.

In a sample with stronger than average wealth persistence, Clark & Cummins found that at maximum 43% of the capital stock in a given generation was derived from inheritance, with at least 57% created de novo. In other words, wealth creation de novo accounts for most wealth. The reason wealthy families’ wealth persists is not because of its direct transmission, but because of the transmission of the tendencies that underlie wealth creation:

[Wealth] correlates strongly across generations mainly because of the inheritance of educational and occupational status, and not because of wealth transfers themselves. Changes in inheritance caused by largely random shocks to sibling numbers in the nineteenth century were substantially offset by changes in the savings behavior of children. Increased taxation of inheritances in this case may be ineffective in reducing wealth inequality.

This result is, of course, consistent with others results, like those concerning slaveholders, Mandarins, Jews and other scholars victimized by the Nazis, “Enemies of the People” sent to Gulags, people who win lotteries, and more. So when elites circulate, it is just that, and not, in general, the demise of eliteness. People can lose everything, but so long as they have their abilities and beliefs and they can transmit those abilities and beliefs to their children. Through persecution and separation, eliteness will persist. And it does persist.

So to understand why circulation happens, and why elites are able to have an influence when they go somewhere despite there being preexisting elites, consider the case of the University of Toronto Medical School and its Jews.

As you can see, Jews are highly overrepresented among medical students, and they are currently the most overrepresented group. But, they used to be overrepresented to a more extreme degree. This is the case despite the fact that the University of Toronto imposed a quota limiting Jewish admissions in 1942, which remained in effect until 1959.

The reasons for the Jewish decline are not to be found in substituting medical educations for other doctorates, as Jewish representation among PhDs has also declined in more recent cohorts. As such, we have to consider the possibility that it was the increase in other relatively elite immigrant groups that explains this. In plainer terms, Jews were displaced by highly-motivated and capable13 East Asians, South Asians, and Middle Easterners. With more elites, Jews (and other groups!) have had to compete more vigorously, so they’re no longer able to attain their peak level of eliteness.14

Say we want to intentionally circulate out elites. We want a group that’s as capable as our current elites, but which has different interests that are more desirable to us.

The means to accomplish this is immigration.15

Immigration allows a nation to choose its future, because the elites it imports will make that choice for it as they go about living their lives in their new home.

If a nation imports a million Ashkenazim, it will soon see Ashkenazi dominance of its politics. It’ll also find that the imported elites dominate both sides either de facto or just in some capacity, like as thought leaders. The nation may also find that the imported group disproportionately favors one or another side of the aisle. That is the ever-present gambit that immigration-based elite circulation offers: you will get elites, but if you’re careless, you may end up with more of a type you don’t want than another, even if you can find plenty of gems among the imports.

A nation that leverages immigration to benefit from importing elites can readily expand its smart fraction, and it can even improve its politics too. But there’s risk: because elites matter so much, there’s hope to make things better, and there’s also the opportunity to ruin everything. Instead of improving a nation through obtaining a thousand Amjad Masads, careless immigration policy may end up damning it to experience a thousand Timnit Gebrus.

The first response I read came from Sebastian Jensen. Jensen took issue with several of Hanania’s points. Firstly, he argued that Hanania was wrong to use the example of unclear GDP per capita calculus. The error, per Jensen, was that this was too narrow a focus, and there are many externalities to low IQs that Hanania neglected. This is similar to Cofnas’ concern he left stated on Twitter. The second issue was that invoking dysgenic change as a reason to be unconcerned with low immigrant IQs is a non sequitur. This seems apt. Hanania’s case was effectively “Who cares if we get shot if we’ve already been stabbed?” and Jensen’s reply was that Hanania is a defeatist.

The second response I read came from Joseph Bronski. Bronski focused on four negative externalities of specifically non-White immigration that he alleged Hanania neglected. The first was crime, the second was fiscal impacts, the third was impacting politics such that there’s increased redistribution to non-White people, and the fourth was that non-White immigration will reduce freedom. Let’s go point-by-point.

His point on crime seems fine. He noted that Hispanics have an age-controlled violent crime rate that’s about 50% higher than the White rate. Since most Hispanics are part of a fairly recent émigré, this seems alright to note. Bronski does not fall for Unz’s error of double-adjusting for age or conflating reduced per capita rates of crime with absolutely reduced levels of crime perpetration.

His point on fiscal impacts is dead wrong. The fiscal benefits of immigration are often noted by economists and they’re certainly not faking them. You cannot compare tax revenues to benefits receipt by race to obtain the actual fiscal impacts of different racial groups for the simple reason that we live in market economies where we all work together. Because of this, it may naïvely appear that one racial group has a substantial and negative net fiscal impact, while actually, they can be completely positive because the benefits are enjoyed by members of other races. If a Hispanic immigrant works a job that enables a White person to work a better one, but they themselves use welfare and their individual contribution appears to be negative, that estimate is wrong: you have to factor in the benefit to the tax revenue generated by the White person they allowed to move up. Despite their poor aggregated showing, Hispanic immigrants actually do have positive fiscal effects for this reason.

The point that non-Whites like big government is fine. It’s clearly not wrong, but it’s less clear how much this matters. Much of government action is constrained locally, and thanks to spatial heterogeneity in births and migrant destinations, most of the U.S. is likely to remain majority White for a very long time even after the country becomes majority non-White. There’s also the point that non-White groups often have very low levels of political participation. Some groups have discovered that methods like ballot harvesting and busing can reduce the political participation gap, and perhaps more importantly, that the gap is smaller for members of later generations of non-Whites and for immigrants who are given English language training. It’s also abundantly clear that left-leaning Whites, among others, will lobby on behalf of non-Whites. To the extent those efforts can take off, they can matter. Some Republicans have tried to cope with this by arguing that non-Whites can be won on the issues. But they do not want that in all reality, since to win on the issues means to move left and to enable additional leftward movement by the Democratic party. Some people cite places like Florida, where Hispanics have allegedly flipped Republican, but they don’t know that this was compositional in the most recent (2022) election, and it really reflected a Democratic failure to maintain motivation in their base rather than a change in allegiance from blue to red.

Hanania makes the point that diversity actually undermines welfare state support. It’s hard to imagine the welfare state as something that, in its modern form, would be possible without non-White support, but there is something to this that I’ll return to below.

The point that non-Whites are less supportive of Constitutionally-enshrined freedoms is also fine. Again, it’s clearly not wrong, but as above, it’s unclear how much it matters. No one can predict the medium-to-long-run with a great degree of accuracy, but there have been many recent wins on the 2nd Amendment front, although the 1st Amendment might have already been run through with scissors. If it’s true that immigration will lead to more votes against these freedoms, then yes, it is, of course, rational not to support it.