The Fruits of Philosophy

Bradlaugh-Besant and Early Family Planning

Birth control is ancient.1 The earliest records of contraceptive methods are more than 3,000 years old. Genesis mentions and condemns using coitus interruptus as a means to avoid impregnation. The ancient Greek city of Cyrene was dependent on the trade of silphium, which was probably a spice, but may also have been an abortifacient, like many other plants including the wild carrot, the flowers of the Dr. Seuss tree, the herb-of-grace, and the pennyroyal.

It goes without saying that people have always been having kids, and for practically all of recorded history, they’ve tried to find ways to have fewer of them.

It also goes without saying that we’ve gotten better at preventing births.

Properly-used condoms and birth control pills are extraordinarily effective. With adequate use, they are each ≥98% effective. Even with typical, less-than-proper use, condoms and birth control pills prevent almost 90% of potential impregnations. IUDs are increasingly popular and they’re even more effective, in part because their use is just installation. If a pregnancy slips through these first lines of defense, there’s cheap Plan B2 and safe and reliable abortion as options.

An obvious question one might ask after hearing about the widespread acknowledgement and adoption of birth control methods is to what extent do they explain today’s chronically low fertility rates? A less obvious, modified, version of that question is to what extent do all forms of birth control together help to explain today’s chronically low fertility rates?

There’s plenty of research on the subject, but little of it is particularly useful for isolating the effects of birth control methods in a wholesale fashion. There are many estimates of the effect of the introduction of one or another different birth control method, but they don’t cleanly add together. In other words, we have better answers for the first question than the second one. This inferential problem can be clarified with a relevant example: La Revanche des berceaux.

The Revenge of the Cradles refers to the phenomenon of high Canadien fertility. This was important because, although English Canadians had politically dominated Canada, high Canadien fertility ensured they would not be dispossessed within Québec and it would allow them to have a constant or increasing demographic weight within Canada as a whole, giving them the power to represent themselves in the long term so they can avoid being assimilated into the culture of English Canada. The revenge refers to the 1763 La Conquête. After the English won, Francophone immigration became a non-factor in Canada’s growth and frontier expansion, so all the Canadiens could do to avoid their elimination was give birth.

But La Revanche came to an end with the Révolution tranquille. The Quiet Revolution was a reaction that transformed Québec between 1960 and 1970. Its cultural underpinnings were born in the premiership of Maurice Duplessis, who was known popularly as “Le Chef”, and among liberals as the “Grande Noirceur” or in English, the Great Darkness.

Duplessis was Catholic, and radically so. He was also anti-Communist, anti-Unionist, anti-Jehovah’s Witness, corrupt, and virulently anti-Semitic.3 He was accused of buying off voters with alcohol, food, and household amenities, and, as documented by Abella & Troper, in 1944 he delivered a rousing speech in Sainte-Claire in which he claimed the Liberal party was being funded by a Jewish organization of his own invention, one “International Zionist Brotherhood.” The alleged point of this funding was to obtain the entry of some 100,000 Jewish refugees into Québec. In part because of beliefs like this, Duplessis was popular: he played to sentiments common among the province’s staunch Catholics and he was especially popular among rural voters, whom he showed great favoritism to.

His time in office would be spun as one polarizing disaster after another. Duplessis’ favoritism to rural areas was said to come at the expense of the urban population and, relative to the rest of Canada, it resulted in underinvestment in social services and infrastructure. His support from the Catholic church waned after mismanaged union strikes, but the final straw was Bill 19, which stripped trade union accreditation from any union that had a single communist member. After this, the church flipped towards supporting union members over Duplessis’ Union Nationale. The Padlock Law he passed was an unpopular criminalization of the dissemination of communist propaganda and he appeared weak after it was overturned by the Canadian supreme court. Many events occurred which turned large swathes of the population against him. His final humiliation was when he revoked the liquor license of a Jehovah’s Witness who took him all the way to the supreme court and beat him shortly before he died.

Within a year of Duplessis’ death, his successor had also died and the people of Québec had had enough. The Liberal Party was swept into power with the promise of reform and the establishment of a Québec for French Canadians, not the English Canadians who were perceived as recently discriminating against French Canadians after the Richard Riot, and who made up the upper crust of everywhere in Canada including Québec.

The Quiet Revolution was a period of intense change in many areas: education, infrastructure, government, and certainly culture. The changes came at people fast: Hydro-Québec incorporated other large, private electricity distributors and became the main supplier of electricity in the province; cégeps became a normal part of the educational experience for young French Canadians; the Castonguay-Nepveu Report gave birth to the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec, bringing universal healthcare to the province; agencies were established to manage the province’s pensions and investments; Québécois self-identification was born and the welfare state came shortly thereafter; la Loi sur la capacité juridique de la femme mariée gave married women the right to form contracts, own personal property, and seek employment without having to go through their husbands. When the revolutionary part of this era of the Liberal Party’s rule came to an end is debated, but it’s generally considered to have coincided with Pierre Trudeau’s invocation of the War Measures Act against the Front de libération du Québec members who kidnapped Pierre Laporte and James Cross in Montreal in 1970. In other words, all those changes happened in a single decade.

Perhaps the most important change of the Quite Revolution was that religion had made its way out. The province secularized at an astounding rate. Some sociologists and historians have argued accordingly that the decline of Roman Catholic influence played a major role in the decline of Québécois fertility. This seems to be a factor whose influence can be isolated in the decline of French fertility and the historical spread of the demographic transition from France, so it’s reasonable to conclude it mattered here.

But here is the problem: there were too many changes. Consider that reforms like the implementation of universal healthcare reflected a broader trend, as it was also established throughout Canada in other places between 1968 and 1971, not just in Québec in 1969. In fact, there were too many changes globally to clearly isolate an impact that was specific to Québec! Just take a look at the fertility trends for the province, Canada as a whole, the U.S., France, and England and Wales.

Everything is pretty similar, and they all converged to a similar level. This makes chalking fertility outcomes up to a revolution that took place in one place difficult—we haven’t leveraged any identifying variance, so attributing the changes in Québec to the Quiet Revolution is informal. Was it secularization? Was it women’s freedoms? Was it women’s work? The Quiet Revolution might have played a role in the province’s fertility decline. I assume it did play a role, and for many reasons. But I don’t have anything more than ‘something similar happened elsewhere’, and ‘cross-sectionally these factors are related to fertility and they changed in Québec’.

But let’s return to the original topic: do we know what effect birth control and family planning had in virtual isolation?

The Country Quack?

Based on his one surviving photograph, we know Charles Knowlton was a pretty handsome guy. He was also an oddball.

Charles Knowlton was born on May 10ᵗʰ, 1800 in Templeton, Massachusetts to a family of modest means. His grandfather was a Revolutionary War captain and a state legislator, but his father was just a farmer. As an oddball, he claimed the circumstances of his birth were simply relayed to him: “I have been informed, but whether correctly or not, I can never know—however confidently I may believe—that I, Charles Knowlton, was born in Templeton, Worcester Co., Mass, on the 10th of May, 1800.” His father did well enough to afford him the luxury of attending school, so he was literate, numerate, and even so qualified as to spend his own time teaching shortly after turning eighteen.

But Charles was a bit of an obsessive. He believed he suffered from gonorrhea dormientium, otherwise known as nocturnal emissions. Seemingly out of shame towards his condition, he became obsessed with masturbation and orgasming, and believed his nocturnal emissions were destroying his health. In his state of hypochondria, he began to self-medicate with opium, tree bark, iron, and more, to find any means to stop himself from ejaculating in his sleep.

This bout of hypochondriasis was evidently driving him into poor health, as his habits made him, a man who was very tall for the time at 5’11”, weigh in at a paltry 135 pounds and exist in a state of constant illness.

A Knowlton family friend, one Richard Stuart, came to visit the Knowlton household in 1821, and Charles apparently took quite a liking to him. Richard was a mechanic who had been experimenting with electricity and, in particular, with electrical treatments for all sorts of illness. It’s hard to say if what saved Charles was the poorly-described treatments Richard gave him or the fact that shortly after moving in with Richard, he married one of his six daughters, stopped self-medicating, and got “the ‘vital fluid’” put back into him. Interpret that on your own.

A year after moving in with Richard and being cured of his masturbation madness, Charles enrolled at Hanover Medical College (known today as Dartmouth). After a short time enrolled, Charles heard a rumor that the school would pay $50 per cadaver. So, in his desire to make a quick buck, he started robbing graves while he was traveling.

Charles dug up two corpses and brought them to the college, where he was told by his anatomy professor that there was no use for the cadaver that made it, as the warm weather had caused decay to set in. He didn’t receive the $50 he had hoped for, but he did get $20 to dispose of the body.

This grave robbing habit continued for some time, with the new purpose being to obtain valuable anatomical knowledge through dissections. Charles was eventually caught in 1824, tried for grave-robbing and disposing of bodies, and convicted of illegal dissection, for which he served two months in the county jail. In the previous year, he had received his medical degree, with his dissertation being on the importance of the need to obtain hands-on dissection experience to really understand anatomy.

After obtaining his degree, Charles skipped around with his family until he wound up in Hawley, where he had the first four of his five children while continually failing to build a practice. While in Hawley, he published a practically schizophrenic volume entitled Elements of Modern Materialism, in which he challenged religious dualism and concocted something akin to early behaviorism. The book was not popular. With a horseload of books in hand, he traveled down to New York City and failed to sell a single one, despite his contention that the book would make him as acclaimed as John Locke.

His long-term abode would end up being in Ashfield, where he finally managed to start a successful practice with a local doctor and he would continue to gain an odd reputation: on Sundays, he would play the violin around town instead of attending the church, and on his itinerant treks throughout Franklin County as its primary country doctor, he could frequently be seen bringing his carriage to a halt and lying down on the side of the road until his bouts of angina passed.

The defining moment of Knowlton’s career was when he wrote The Fruits of Philosophy, or the Private Companion of Young Married People. The book begins with a chapter entitled “Philosophical Proem”, which contended, contrary to the received wisdom of the time, that sexual desire was not in itself evil and, “When an individual gratifies any of his instincts in a temperate degree, he causes the amount of human happiness to exceed the amount of misery.” But this wasn’t what Fruits was really known for.

The second chapter was entitled “On Generation”, and it made the case that birth control ought to be used to prevent overpopulation, curb poverty, and eliminate crime, while reducing illegitimate birth rates and encouraging couples to pair off earlier because they wouldn’t have to fear getting pregnant if they began living together.

The book was full of what was, at the time, scandalous material, like a chapter on female genital anatomy with scientifically correct terminology and descriptions of function that encompassed the pleasure-generating aspects of the clitoris.4 The book also included folk remedies for infertility and impotence, described how conception occurred, and included a great deal about Charles’ personal philosophy.

But what really set people off was a chapter reviewing birth control methods, and, critically, arguing for new, easily-implemented ones, like spermicidal douching. He explicitly argued that these could be used for the purposes of pleasure-seeking, as when he said a syringe of “zinc, of alum, pearls [of potassium sulfate], or any salt that acts chemically on the semen” would cost “nearly nothing; it is sure; it requires no sacrifice of pleasure; it is in the hands of the female; it is to be used after, instead of before connexion, a weighty consideration in its favour.”

Charles did not intend for Fruits to be incendiary; he basically just wanted to help young couples, but he knew there was a risk to disseminating his work. In fact, he actively hid his book, and sold it at a relatively high price, only to select patients. He really did seem to give his best to limit the book’s circulation. But eleven copies were stolen from the secret box he kept in his office and his first edition did result in 2,500 sales in just over a year’s time, so his honest efforts might have also been hasty.

After a short while, a scathing critique of Fruits came out in the Boston Medical Journal, including the line “The less that is known about [Fruits] by the public at large, the better it will be for the morals of the community.” The publisher of The Boston Investigator caught word and printed a second edition that made it much more popular, but also landed Charles in legal trouble in Taunton, in which a case was built against him on the grounds that his book was "a “libel against the public morals”.

In other words, he was being tried for obscenity.

A jury of credulous strangers watched Charles defend himself against the reading of the most poorly interpreted excerpts from his book, and they ended up finding him guilty and charging him a $50 fine and the court fees of $27.79. The prosecutor felt guilty about the fines and turned over the court fees to Charles and one of the men on the jury approached Charles after the case to buy a copy of the book. This wasn’t all bad. But shortly before the guilty verdict had been rendered, another physician brought different obscenity charges against Charles. Since he was busy defending himself in the first case, he had a lawyer for this one, and the lawyer advised him to plead guilty. So shortly after losing the first case, he lost the second and was sentenced to three months of hard labor, in spite of his heart condition.

Outraged responses to the trial were printed in The Boston Investigator and disseminated throughout free-thinker circles, but that wasn’t the end of it. To compound Charles’ legal worries, his town minister, Mason Grosvenor, organized a campaign against “infidelity and licentiousness” aimed at him. A grand jury indicted Charles and his practice partner, but after seventeen tense hours of deliberation, the jury failed to reach a verdict and the men were released. Grosvenor didn’t stop, however, and he kept pushing for his congregation to “crush” Charles.

A year later, Grosvenor gave up, left town, and Charles’ life continued on, full of different troubles—with his health, with his kids’ health, with family, with work… and on and on. Charles eventually passed away, likely due to his angina, a few short months before his fiftieth birthday.

Charles was an oddball, that’s certain. Throughout his life, he felt he was underappreciated. But after his death, his legacy would grow to a level he couldn’t have dreamt of, and a level that’s critically important for this blogpost.

The Great British Test Case

Fruits of Philosophy would see its heyday after a pair of secularist activists concocted a scheme to publish and distribute it in violation of Britain’s Obscene Publication Act of 1857. The point of this effort was to provoke a test case to see if they could challenge the law, which had already been brandished against a publisher and a seller of the book.

The book was first published in England in 1834 by James Watson. But after poor sales, the text languished without provoking any controversy until it was read by Charles Watts around 1875. Charles was an activist with the National Secular Society, and he sought to promote his cause in every arena he could, from reducing the influence of the church to promoting the control of fertility. So he bought the plates for the book and began to publish and promote it.

A Bristol bookseller, Henry Cook, had provoked the ire of the local Society for the Suppression of Vice by selling the book, which they alleged contained obscene illustrations of an unclarified nature. For selling the book5 in violation of the Obscene Publication Act, he was sentenced to two years of hard labor.

Invigorated by their win, the Society pressed further against the book and targeted Watts, who crumpled immediately in response to the court case that was brought against him. He pled guilty, was ordered to pay court fees, and his sentence was commuted because he agreed to destroy the printer’s plates and his stock of Fruits. He believed it just wasn’t worth the fight.

Fellow National Secular Society members and secularist activists Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant were incensed over Watts’ lack of a spine, and they wanted redemption. They sought to use Charles’ legal acumen to remedy the wrongs they felt had been levied against Watts, Cook, and society at large through the suppression of Fruits.

So they needed a test case.

The pair set up the Freethought Publishing Company at 28 Stonecutter Street and eventually turned the company into the headquarters of the National Secular Society. But before that, their current mission was to republish Fruits. They sought the help of a Dr. George Drysdale to modernize the manuscript and began printing copies.

Next was to distribute it.

They advertised that they were going to be selling the book at the local guild hall on Saturday, March 24ᵗʰ, 1877. But before the date came about, they alerted the police that they would be there.

They really wanted to provoke a test case, and this was the optimal means to do it. Fruits did not contain any material that was unknown to doctors or which was unavailable in other publications. The difference between this and earlier works containing the same information was that they would sell Fruits for six pence, or, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, a trifling £5.67 today.

Their efforts paid off.

Within twenty minutes, they had sold five hundred copies of Fruits, including a few to policemen. People were loving it. And then, the police stepped in and Bradlaugh and Besant were arrested for violating the Obscene Publication Act. All according to plan so far.

On Thursday, April 5ᵗʰ, the charge of breaching the Obscene Publications Act was laid down and the trial could commence. Between their arrest and the trial’s start in on June 18ᵗʰ, the publicity their arrest earned them allowed their publishing company to sell no fewer than 125,000 copies.

Bradlaugh debated with the presiding Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Cockburn, that they ought to be allowed a jury for their case, and they were granted it. Cockburn might have been sympathetic, as he gave Bradlaugh and Besant considerable leeway in presenting their case.

Besant argued effectively that poor women needed the ability to obtain cheap contraception. The doctor who edited the book, Drysdale, testified that women’s attempts to induce amenorrhea through extended lactation caused their children to be deprived of proper food. Others, like H.G. Bohn testified that the group who had instigated the overuse of the law, the Society for the Suppression of Vice, was going overboard in their attempts to suppress vice, as they even wanted to ban the Greco-Roman classics!

On the prosecution’s side, the solicitor general, Sir Hardinge Giffard, alleged that through publishing Fruits, Bradlaugh and Besant published “obscene libel” that was “calculated to destroy or corrupt the morals of the people.” Per case law, any text that had the effect of corrupting people’s morals was definitionally obscene. Echoing popular prudish sentiment, Giffard stated that “This is a dirty, filthy book” and “no human being would allow that book to lie on his table; no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it.”

But the state was not as clever as Bradlaugh and Besant. Bradlaugh had planned for Besant to throw a wrench into Victorian gender norms. Besant was not a jurist like Bradlaugh, but Bradlaugh wanted to let her represent herself to stir up the papers, as this could be a high-profile example of a woman representing herself. Or at least, appearing to.

Victorian law, like most law until the last few generations, subsumed the civic and legal identity of the wife into that of her husband. Besant’s apparent self-representation made the papers fly off the presses, as thousands across the country kept trying to find more details on the case. It certainly helped that Besant had the voice of a reformer, arguing that she undertook the case for “hundreds of the poor… it is they for whom I defend this case!”

Besant provided a Malthusian explanation of poverty. She described how in the “savage nations”, population was checked by nature, but in Europe, she argued, they had thrown off the reins of nature. Now, people were cleaner and better-fed, but this made the overpopulation risk all the more palpable. She attributed the economic downturn they were in to this supposed overpopulation, which managed to make her claims very popular among the large, disaffected public.

Ultimately, Bradlaugh and Besant would lose their trial. After four days, they received a guilty verdict. But, Bradlaugh was not content, for he had spotted a loophole: when they were convicted, the prosecution had failed to provide the exact wording that made their publication of Fruits obscene. Cockburn referred the case to the Court of Error who agreed that Bradlaugh had found a technicality, and they summarily set aside the judgment.

Bradlaugh and Besant were free and more than 250,000 of their extremely cheap guides to family planning and birth control were sold over the next three years. Against Comstock’s wishes, the popularity of this text had grown to such a degree that, by the 1890s, a dozen different editions were circulating in the U.S.

The population learned about birth control immediately, and a genre of very popular books on the topic had been borne. This is the event we will use to assess the impacts of sudden, society-wide mass awareness of birth control methods.

Where Are All the Babies, Guv?

In England particularly… the drop appears suddenly about 1878. The coincidence of this change with the propaganda called forth by the Bradlaugh-Besant trial is too significant to be ignored. The deeper causes of birth restrictions… were latent in general social conditions…. But the ill-starred prosecution gave to slow-gathering forces instant and overwhelming effect. - Field (1931, p. 244)

You don’t need glasses to see when the Bradlaugh-Besant trial happened.

After the trial took place, fertility immediately fell. But as in Québec, are we certain that was it?

In this case, probably, since this was a much sharper and more sudden downturn than the one that may have resulted from the Quiet Revolution. The Bradlaugh-Besant trial happened in one year and the effect was an immediate and largely unabated decline in the birth rate.

The best evidence that the cultural change inspired by this trial was what caused Britain’s birth rate to plummet was provided in a 2019 paper from Beach & Hanlon.

Their first chart painted a telling picture of fertility trends following the Bradlaugh-Besant trial.

In this close-up view, the enormous effect on fertility rates is unquestionable.

The trial clearly had its effects on public knowledge. The campaign to make the public aware of family planning methods by Bradlaugh and Besant was a successful one and all you need to do to see that is to look at the number of articles mentioning them, Fruits, or the “population question” by month and year:

Thankfully for us, this upsurge in articles was not uniform: there was regionally differential exposure to newspaper articles on the trial! The map on the left depicts the number of articles published within 25 kilometers of each district of England and Wales. As the chart on the right shows, places with relatively greater exposure saw their fertility fall more.

What’s more, these regional differences eliminate several alternative hypotheses! For example, we know this was not a regionally socioeconomically stratified phenomenon. The decline was due to exposure, not the socioeconomic characteristics of exposed regions: whether the region was rich or poor; if it specialized in textiles, mining, metals, or farming; if it was urban, rural, or non-Welsh6—regardless, the effects were comparably driven by exposure.

And this result was robust to the use of alternative measures of exposure as well: distance from London; the number of articles published within twice as great a distance; exposure to the writings of women’s activist Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon in the 1860s (whose name is conveniently unique enough to serve as a control for local liberal biases); whether the article’s focus was Bradlaugh & Besant or something else in addition to them; whether there was direct reporting on the trial; whether the articles were long or short—regardless, there we have it!

The results by region and level of population density were similarly consistent:

The Bradlaugh-Besant trial is an unambiguous case of what the effects of the sudden, generally novel, society-wide diffusion of knowledge about birth control and family planning can do. But Beach & Hanlon weren’t finished yet. They had much more to show.

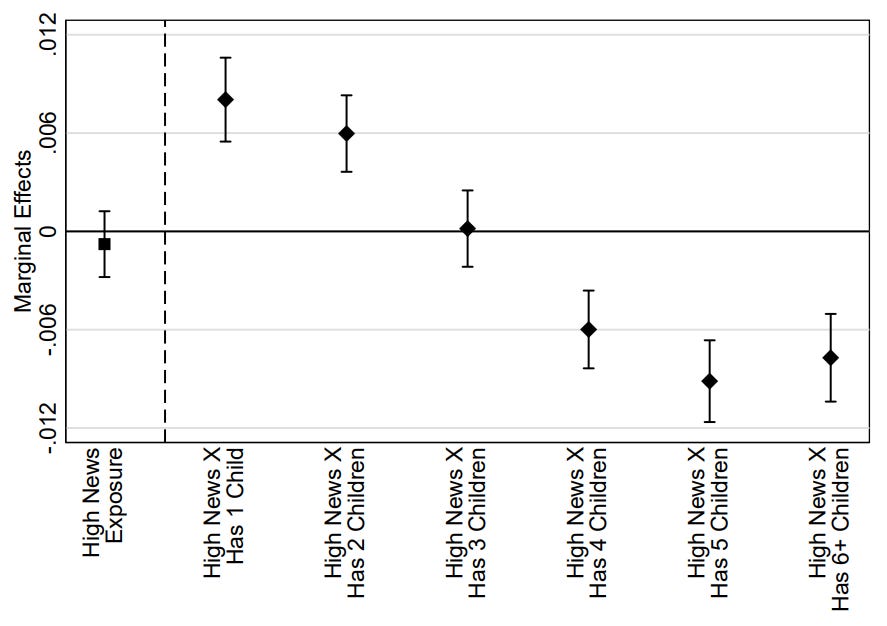

Firstly, they qualified the result: Bradlaugh-Besant was about birth control, not birth reduction only. To show why this matters, they provided this result: post-trial (1878–81) fertility patterns among households with kids in highly-exposed districts.

In total, there was a nonsignificant reduction in the number of additional children in households more exposed to the trial in the immediate post-trial period. The thing that really stands out is that the effect was parity-dependent: average families didn’t change their fertility, small families had more kids, and large families constrained their fertility. Over the generations, typical households would constrain their fertility more, but that was not the immediate impact for those who already had kids. However, to obtain immediate declines in fertility, what did happen was a decline in first births. As evidence of that, the ages of mothers increased after the trial.

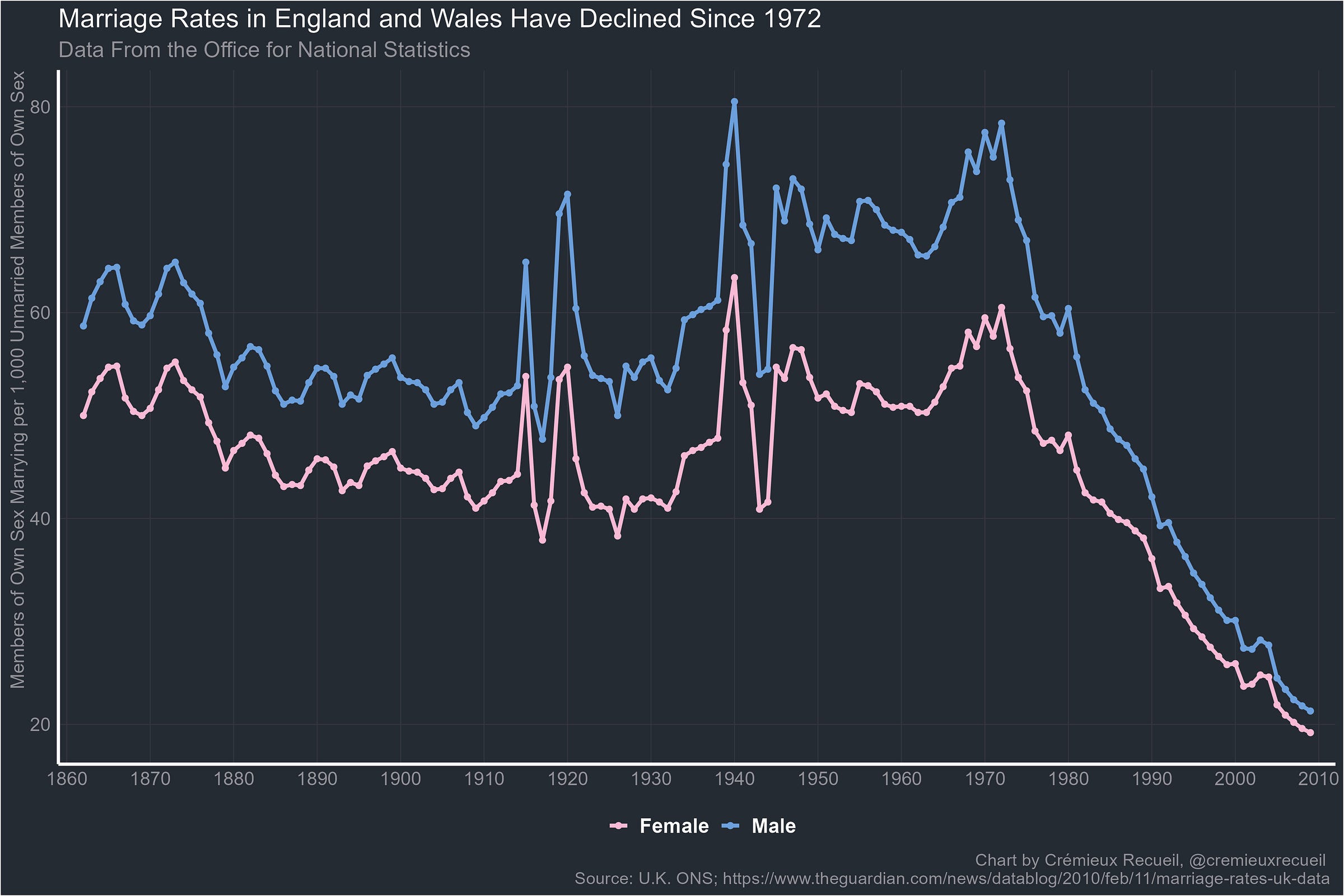

Before showing Beach & Hanlon’s other results, I wish to add something to their analysis. Using British Vital Statistics, family formation via marriage did not markedly decline in a way that could explain these results. In fact, the major decline in British marriage rates occurred after the legalization of no-fault divorce with the passage of the Divorce Reform Act 1969.

And now comes the international evidence!

Firstly, no other country mirrored the English and Welsh pattern, except Scotland. That makes this a truly British result.

Next, although it should be considered more preliminary, linguistic proximity to Britain predicted fertility effects in other countries: the closer the country, the more its fertility fell too. This analysis was extended in the study, but without charts. The extensions featured the use of different measures of linguistic proximity, measures of religious proximity, genetic proximity, different time windows, additional controls, the addition of other parts of the Anglosphere, subsetting to Europe only, and comparisons with placebo regressions. The results were robust, even if this chart looks somewhat unconvincing.

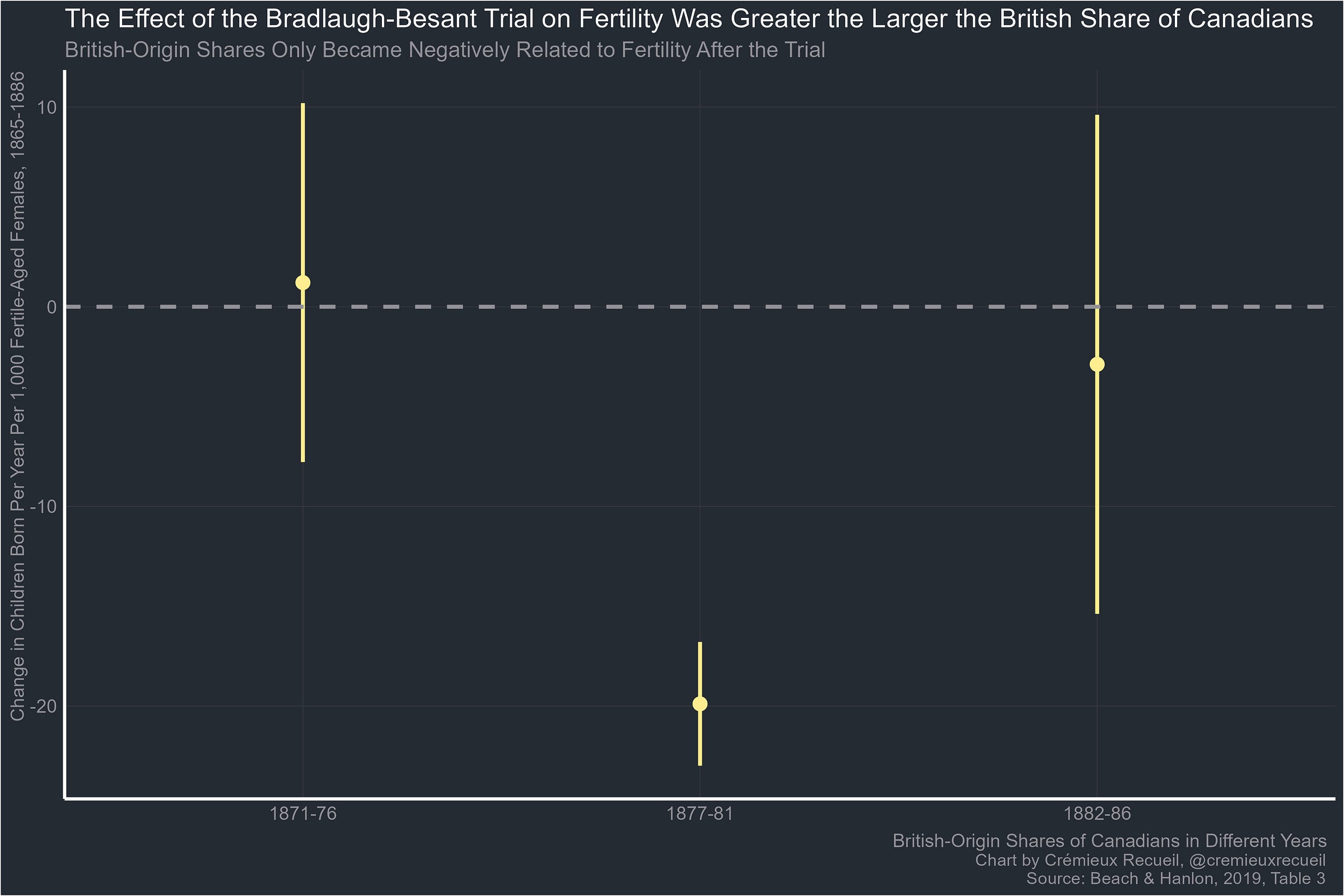

Results for Canada followed.

Remember the Revenge of the Cradles? As it just so happens, that might be attributable to the Bradlaugh-Besant trial. At least between 1846 and the trial, Nova Scotia and Ontario had comparable or higher fertility than Québec; after the trial, Québec enjoyed a sizable fertility advantage.

Across Canada as a whole, British-origin shares of the population were not at all associated with fertility prior to the trial. But shares immediately after the trial strongly predicted declines in the fertility rate. Shares later on didn’t have an independent effect.

As robustness tests, the Beach & Hanlon also showed that this finding held up within Québec, controlling for the shared of children in school, and the share of illiterate adults, among English, Scottish, and Irish7 immigrants, and without weighting. But most critically, they showed that all other immigrants were unaffected: their effect on fertility was positive, nonsignificant (p = 0.57), and significantly different from the British effect (p = 0.01), so the evidence that the trial had a cultural impact that was uniquely British is well-supported.

The trial’s effect pictured above also held up with alternative measures of British shares. For example, simply using the non-French share, the non-Catholic share, or the share of attendees of the churches of England and Scotland replicated that result.

The aggregate post-trial fertility pattern among British households in Canada is a bit different from the high-exposure post-trial fertility pattern in Britain mentioned earlier. This one was almost strictly negative. But, unlike in Britain, there was not evidence of a delayed first birth effect. In fact, the opposite was observed: after the trial, British households featured younger mothers and fathers.

The analysis didn’t stop there: next up was South Africa.

In the Cape Colony, there were two primary co-resident European ethnic groups represented among the White population: the British and the Dutch Afrikaners. The Afrikaners largely arrived to the Cape in the 17ᵗʰ and 18ᵗʰ centuries, whereas the British arrived en masse in the latter part of the 19ᵗʰ century. The Afrikaners were in the majority and mostly did not speak English.

The results in the Cape Colony replicated the ones from Canada: the more the British share, the greater the decline in fertility, even controlled for literacy and other immigrants shares which, incidentally, were not related to fertility. Moreover, the share of non-Dutch Reform churchgoers also predicted reduced fertility.8

Replication also followed in America.

State-side, British household fertility followed something like the high-exposure pattern from Britain after the trial.

Based on all of this cross-national evidence, the fact that the trial made it legal to use the British mail system to send information about contraception and family planning, and the appearance of effects on immigrants and existing British households with more limited impacts on non-British populations, we can see that the Bradlaugh-Besant had an unambiguous impact that was culture-specific. In other words, it really was the perfect case-study of what happens when you rapidly introduce and normalize birth control and family planning.

Connecting Cultural Dots

The unambiguous impact of the Bradlaugh-Besant trial had an antecedent a century prior. In a recent paper by Guillaume Blanc (summarized on Twitter), he provided this graph:

This clearly shows that the decline in fertility in France took place long before the British one. Blanc’s powerfully-argued and cleverly-conducted work also showed that this decline was due statistically to the rise of secularism.

The effect of secularism on fertility is not as simple as ‘lose belief in g-d, stop having sex’. It’s a tapestry of interwoven changes in customs and moors around many topics, not least of which is fertility. Several of the changes experienced in France were actually articulated by Annie Besant during and after the trial.

Besant explicitly cited French teachings and credited the state’s rising secularism and the weakening of religious beliefs with the decline in French fertility and what she perceived to be the superiority of economic conditions in France. In an issue of The Malthusian9, she argued that her arguments had showed “how absolutely necessary it was to limit families as the French did” as “the Laws of England are still tainted with that spirit of bigotry and intolerance, which has been left as a legacy to us from the times of our barbarous ancestors… whilst in France it has been found necessary for the families to abstain from denunciations addressed against conjugal prudence, the misguided jurors of England still prefer starvation and famine to thoughtful and praiseworthy regulation of families.”

Given this, one has to ask: why didn’t fertility in Québec collapse like British fertility did after Bradlaugh-Besant? The answer might be La Conquête, which happened not long after or slightly before the fertility decline in France proper was set in motion.

As a result of becoming a part of the British Empire, the cultural evolution of Québec was cut off for a long time from France, and, of course, French Canadians did not want to emulate the British. So, they kept their faith longer than the denizens of France, making the Revanche something that can be credited to the British at least two times over.

This also supports the Quiet Revolution’s impacts on fertility. Enough time had passed to reduce ethnic tensions, and institutional convergence between Québec and the rest of Canada—and thus the Anglosphere—visibly occurred. Institutional convergence is part of the means through which cultural convergence can occur or be reflected, and since we know that convergence happened, it’s not a stretch to think the other one did too. In fact, it seems hard to imagine institutional convergence without some degree of cultural convergence.

A final piece of evidence for this theory requires considering the case of… everyone.

The demographic transition began in and spread from France.

As cogently argued by Spolaore & Wacziarg, the secular fertility-constraining behavior that emerged in France diffused to regions with greater linguistic proximity to France. If a place was nearer to the French cultural frontier, they adopted family planning practices like theirs earlier and their demographic transition would set in accordingly.

Britain and its possessions had a cultural barrier to these practices. Institutions like the Society for the Suppression of Vice were commonplace and frequently mounted vicious attacks against those who wished to promote practices like the ones that had become routine in France. The Bradlaugh-Besant trial tore down that barrier. But as the practices adopted by the British were seen as, well, British, their uptake would take some time to happen in Québec. But when they did set in, there went the birth rate.

A problem with this example is that Québec also adopted new laws around the same time that this could happen which reduced rates of marriage, increased divorce, and overall negatively impacted family formation. Because that channel is important for births, that almost-certainly had a birth rate impact as well. But, I think the fact that this channel was accentuated by the British around the same time speaks to the wholesale adoption of all of the above fertility-constraining factors by Québec, rather than a simple effect of reduced family formation alone. If it were just that, then one would expect the more British areas of Canada where family formation followed similar trajectories to have even stronger reductions in fertility; but no, what happened was convergence.

Can Fertility and Family Planning Coexist?

This post has described a major cause of an important part of world history: the demographic transition. It has not, however, argued that fertility and birth control methods are incompatible.

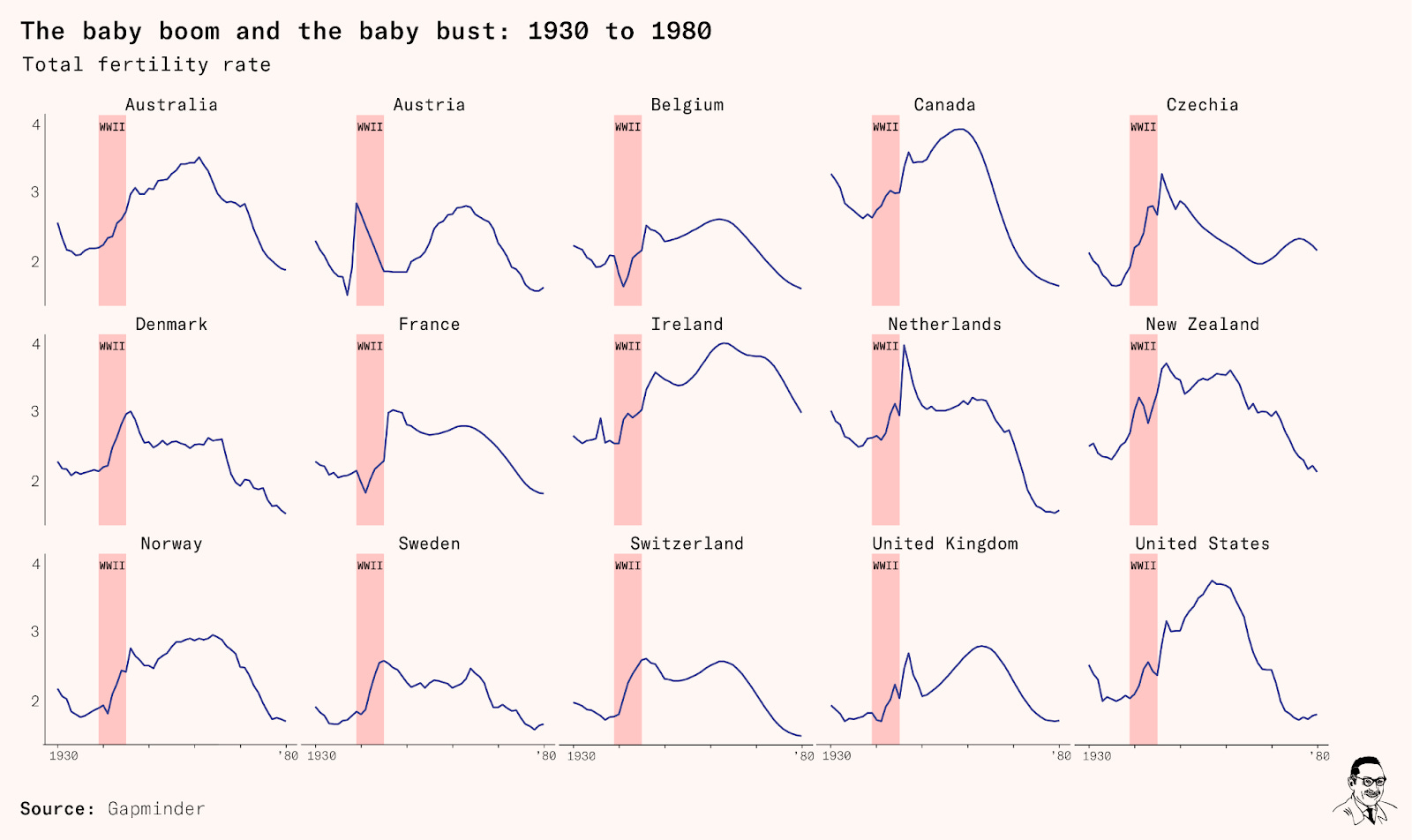

A recent article by Works in Progress described history’s most notable deviation from the near-monotonic demographic dégringolade derived from France: the Baby Boom.

I thoroughly recommend reading that article. It shows that the Baby Boom began before the return from the frontlines, across diverse countries that were differently affected by the second World War. But what really stood out to me was their second plot. Specifically, the bottom row and fourth column: fertility in Britain.

What seems to have happened in Britain is that they had an entering war downturn followed by a larger uptick, a return from war uptick, and a later end of austerity uptick. To me, this seems like a perfect opportunity for someone to better figure out how a more modern population’s fertility can be boosted.

The methods to do this involve exploiting differences between countries and regions in the apparent fertility effects of different policies, events, and practices. For example, using the timing of when war-time austerity measures ended is a simple matter to see the impacts of plausibly exogenous boosts in living standards on fertility. Another method is to see how much antibiotics and other medical improvements mattered through leveraging data on maternal mortality for invention-relevant reasons. Albanesi & Olivetti gave hints to how this could be done when they showed that there were different trends in maternal mortality by “Toxemias”, “Hemorrhage”, “Sepsis”, and “Traumatic Accidents of Labor”. The differences in timings and the relationships with inventions and their introduction could be leveraged to great effect. The numbers of troops from areas who survived and who died are known for the U.S., and probably other countries as well; returning soldier shares could be used to estimate the impact of plausibly exogenous changes in area sex ratios, populations, etc. on fertility. Housing data can be augmented with G.I. bill reward receipt and soldier return data for yet more plausibly exogenous variance in things like housing and local economic performance more generally. Leveraging soldier deaths, one could even leverage synthetic controls very effectively, to estimate the impacts of the receipt of additional benefits by an area had more or fewer soldiers returned from war.

There are certainly more possibilities for investigating why the Baby Boom happened and if it can be replicated. I believe that it might be a fruitful means of understanding what are hopes are for fertility in the future. If all it takes to bring fertility back to sustainable levels is cheap housing and energy, fixing the healthcare system, and reducing the time spent in education, then the future is becoming ever cheaper and the dividends for pursuing it are growing ever larger.

I occasionally use the term “birth control” interchangeably with “family planning”, so it does not only refer to “contraceptive methods.”

And Plan B is certainly better than even relatively recent abortifacients like the Motex and Cote pills introduced in the 1930s, which the FTC said were “not effective as competent and reliable treatments or remedies for delay in functioning of the menses” and “Further, said products do not form absolutely safe or harmless treatments if taken according to directions and are not recommended by famous physicians or generally by physicians, are not always effective as abortifacients, will not prevent conception, and might cause serious injury physically if so used.”

This has been disputed in the book Duplesisis. The alternative explanation for Duplessis’ documented anti-Semitic remarks was that he knew anti-Semitism was very popular in Québec at the time, so he merely chose to play to the voter’s beliefs to great effect.

A section on male anatomy was added in the fourth edition.

As a pamphlet focused on contraception, which I will continue to dub a book for simplicity’s sake since it went by the same name as the original book.

Perhaps. This had a p-value below 0.10, not 0.05. Treating the other sources as bases for a prior, a one-tailed test is justifiable. This is especially justifiable given we know why Welsh results were constrained based on the map: range restriction!

Irish immigrants to Canada at the time were largely Protestants and from Ulster, and, per Beach & Hanlon, “Ireland had much lower fertility rates than England & Wales in the decades after the Great Famine, which may have meant that the Irish-born were more open to changes in social norms surrounding fertility behavior.”

There was less power for this analysis and the results were more sensitive to weighting than the Canadian ones due to the geographic concentration of British arrivals. The result with a control for other immigrant shares was also only p < 0.10.

Quoted by Spolaore & Wacziarg (2019).