The Vast Emptiness of Social Psychology

To be good, maybe social psychology needs to be unpopular

Anyone can be made evil by having them follow orders.

You can gather this lesson from Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, or you can see it ‘confirmed’ in the famous Milgram obedience experiment.

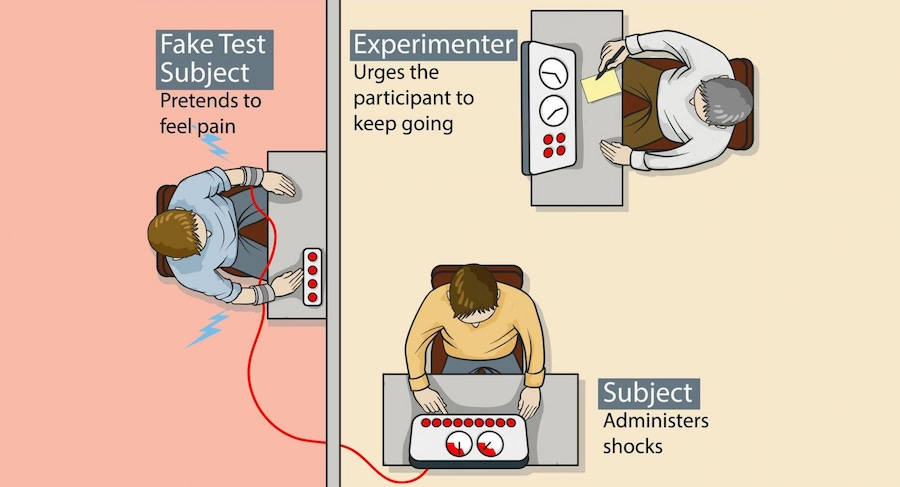

In the Milgram experiment, subjects—the “teacher”—are brought into a room and introduced to their supposed counterpart—the “learner”—and their invigilator—the “experimenter”. After meeting one another, the teacher and the learner are sat down in separate rooms with no line of sight. The teacher is sat down in front of a panel that can administer shocks to the learner, and the teacher can hear the response to the learner when that happens. The experimenter is sat behind the teacher and provides them with commands throughout the experiment, pushing them to administer more and more extreme shocks to the learner as time goes on, despite the learner’s protestations and screams.

Unbeknownst to the teacher, the learner is never actually hurt and is, in fact, a confederate of the experimenter. The teachers are only ever made aware of this fact after the experiment is through, during a debriefing with Milgram.1

Per the typical telling, this experiment illustrated that people were willing to go along with hurting others simply because they were told to do so at the behest of an authority figure, the experimenter. The example people are most aware of for this behavior operating in the real world is that of Nazis working in death camps, killing millions of people because they were ‘just following orders.’

But despite the experiment’s popularity and how well its results seem to fit with the notion that evil can be banal, it really didn’t demonstrate that. For starters, the script the experimenter was supposed to follow to keep the experiment uniform wasn’t followed; instead of using four escalating verbal prompts to keep teachers shocking learners in a clear demonstration of blind obedience to authority, the experimenter frequently deviated, and often ended up bullying the teacher into administering shocks.

The numbers from the study also don’t back up blind obedience. In Gina Perry’s Behind the Shock Machine, she noted that when analyzing only those who claimed to fully believe the experiment was real, obedience to the experimenter was just 33%. Additionally, when Milgram (1974) did the experiment without the wall between the teacher and learner, disobedience was the norm; with friends, disobedience was the rule. Reanalyzing Milgram’s data also revealed that, the more the learner was perceived to be in pain, the weaker the shocks the teacher administered and the less likely the teacher was to administer them at all. In a replication, Burger, Girgis and Manning found that participants were less likely to continue with the procedure the further along it was, with zero people who needed all the experimenters’ prompts being willing to take things further.

We live in a world where those who were more skeptical that the Milgram experiment was real were the most likely to go through with it, and where surety about its reality was related to reduced rates and extents of harm being doled out. That is not clearly a world in which the Holocaust is carried out for banal reasons, by regular people, where just anyone could be one of its perpetrators. Thus, the common interpretation of the Milgram experiments as demonstrating the banality of evil is uncalled for.2

If you give people a little power, you’ll corrupt them.

The famous Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated that if you give regular people a little bit of power, they’ll inevitably abuse it in horrible ways. In essence, the experiment showed that violent, malicious, authoritarian behavior is down to the situation, not to the man. This is lead author Philip Zimbardo’s description:

To show that normal people could behave in pathological ways even without the external pressure of an experimenter-authority, my colleagues and I put college students in a simulated prison setting and observed the power of roles, rules, and expectations. Young men selected because they were normal on all the psychological dimensions we measured (many of them were avowed pacifists) became hostile and sadistic, verbally and physically abusing others—if they enacted the randomly assigned role of all-powerful mock guards. Those randomly assigned to be mock prisoners suffered emotional breakdowns, irrational thinking, and behaved self-destructively—despite their constitutional stability and normalcy. This planned 2-week simulation had to be ended after 6 days because the inhumanity of the “evil situation” had totally dominated the humanity of the “good” participants.

Above and beyond Milgram’s display that ‘just following rules’ can lead to tragic behavior, Zimbardo demonstrated that ‘just being given the authority to hand down rules’ corrupts horrifically.

The guards in the experiment were coached; the prisoners were coached. Both groups of participants treated the most dramatic moments from the experiment like opportunities to practice their improv, and they did so in exactly the ways Zimbardo wanted, because he instructed them to meet his predetermined conclusions. There’s nothing more to this experiment; because it was fake, it reveals nothing about the world for us, and it’s not surprising replication has been unsuccessful.

The psychiatric establishment conspires to invent illness to perpetuate itself, harming patients.

Throughout the 1970s, numerous prominent academics voiced strong negative views towards psychiatry and the institutionalization of the mentally ill. Among them, Stanford’s David Rosenhan espoused the belief that the contemporary psychiatric establishment was institutionalizing the completely normal and fabricating the reasons for doing so after the fact. To prove this, he set out on a nifty experiment, now known as the “Thud” experiment.

Rosenhan recruited seven mentally healthy accomplices to visit psychiatric hospitals and to provide the hospital staff with the details that they were hearing voices in their heads pronouncing the words “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud,” absent any other symptoms. Per Rosenhan, everyone was admitted to a hospital and they received stays ranging in length between one and about seven weeks, and all but one admission received at least a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

But, as with the case of the Stanford Prison Experiment, it was made up.

Rosenhan’s purported evidence that psychiatry had produced corrupt institutions that invented diagnoses and pushed people to identify with life-long, incurable mental illness they needed to be medicated for was based on improper descriptions of the experiment, fabricated quotations, and other forms of lying about what took place, if anything took place at all.

Incidentally, when a replication was attempted in 2004, it also turned out to have never taken place. The best replication for a fraudulent study is a fraudulent study, after all!

In nature and tribes, cooperation breaks down and good people do evil.

Everyone who’s read Lord of the Flies is familiar with the notion that people will act tribally, with deadly consequences. Muzafer Sherif’s famous Robber’s Cave experiment also proves it. Sort of.

Far from demonstrating that tribalism would lead to conflict, the Robber’s Cave experiment really only showed that in unrealistic cases, tribalism can come with conflict. The lack of realism extends from the fact that the aggravating incidents in the experiment were prompted by researchers rather than by the kids’ natural interactions. One particularly indicting case is when the Eagles burned the Rattlers’ flag. The idea and means to do that didn’t come out of nowhere; both the notion and the matches came from the researchers.

Even the climactic, unifying ending of the experiment was something researchers had to concoct. It just wasn’t real, and so it doesn’t really speak to what kids (or people of any age) will do when tribal lines are drawn and the chips are down. To make matters worse, Robber’s Cave was a replication attempt.

Before Robber’s Cave, there was Middle Grove. Sherif’s set-up was similar in basically every respect in this earlier experiment, except the researchers involved weren’t trying as hard to antagonize the kids. They were still trying to antagonize them, to rile them up to take sides, but they weren’t successful. They took kids’ clothing, messed up their tents, and so on, but the aggrieved boys simply had members of the opposing tribe swear on a Bible that they didn’t do the acts, and the conflicts dissolved. In fact, the attempts by the researchers to get the kids to fight were so transparent that the participants ended up skeptical of the researchers’ intent, and aligned against them instead!

Since the results failed to conform to Sherif’s whims, he punched one of his graduate students in a fit of rage and buried the results, electing to only publish his later Robber’s Cave results while Middle Grove languished until it was uncovered much later.

People will go along with the crowd, even when the crowd is wrong

The Asch Conformity Study involved arranging participants between experimenter confederates, and lying to see what people would take. Participants would all look at a target line and a set of lines that might or might not represent the target, and they would have to pick which one matched. The experimenter confederates would all pick a wrong line and, per Asch, many experimental subjects would conform with the incorrect judgments of the people they believed were co-subjects.3

Per the results of the actual experiment, however, two-thirds of people didn’t conform with the experimental confederates, only 5% of subjects conformed consistently, and more of that consistent conformity was explained in rational, understandable ways, such as ‘It’s more likely I have bad vision than that a handful of other people are all seeing the wrong thing.’ After all, how often are a bunch of people going to be wrong about something totally trivial?

This experiment also seems to be strongly affected by individual differences. Some people never fall into the erroneous conformity effect, and in some cases, it seems practically no one in reasonably large samples does so at all.

So to the question of whether people erroneously misjudge matters of fact because they go along with crowds despite having readily available ways to verify the crowd is wrong… it doesn’t seem like there’s much to it, and there’s certainly nothing worrying about the tendency as demonstrated by Asch and those who have sought to replicate his work.

Life outcomes are readily predictable from simple behaviors shown early in life.

Place a marshmallow in front of a child and tell them they can either have it now, or wait for a period of time, and have two, and their response will tell you all you need to know about that kid’s future. The waiters will be winners, and the immediate takers, losers. Or so the common understanding of the Stanford marshmallow experiment goes.

The experiment shows that kids who can delay gratification do better in life, earning higher SAT scores, achieving higher levels of educational attainment, living with lower BMIs, and so on. But the result has had its stature greatly reduced, and what remains is a small correlation. It makes sense that this would happen, since the experiment and most common variations on it don’t provide kids with particularly compelling reasons to delay gratification, and it was always likely that the impact of being a little more patient wouldn’t be huge, even if it would be something.

The more important reason that strong stories like the one from the original marshmallow experiment shouldn’t be believed is that there’s simply no way they could be true. A strong example of why they cannot be true comes from the Fragile Families Challenge.

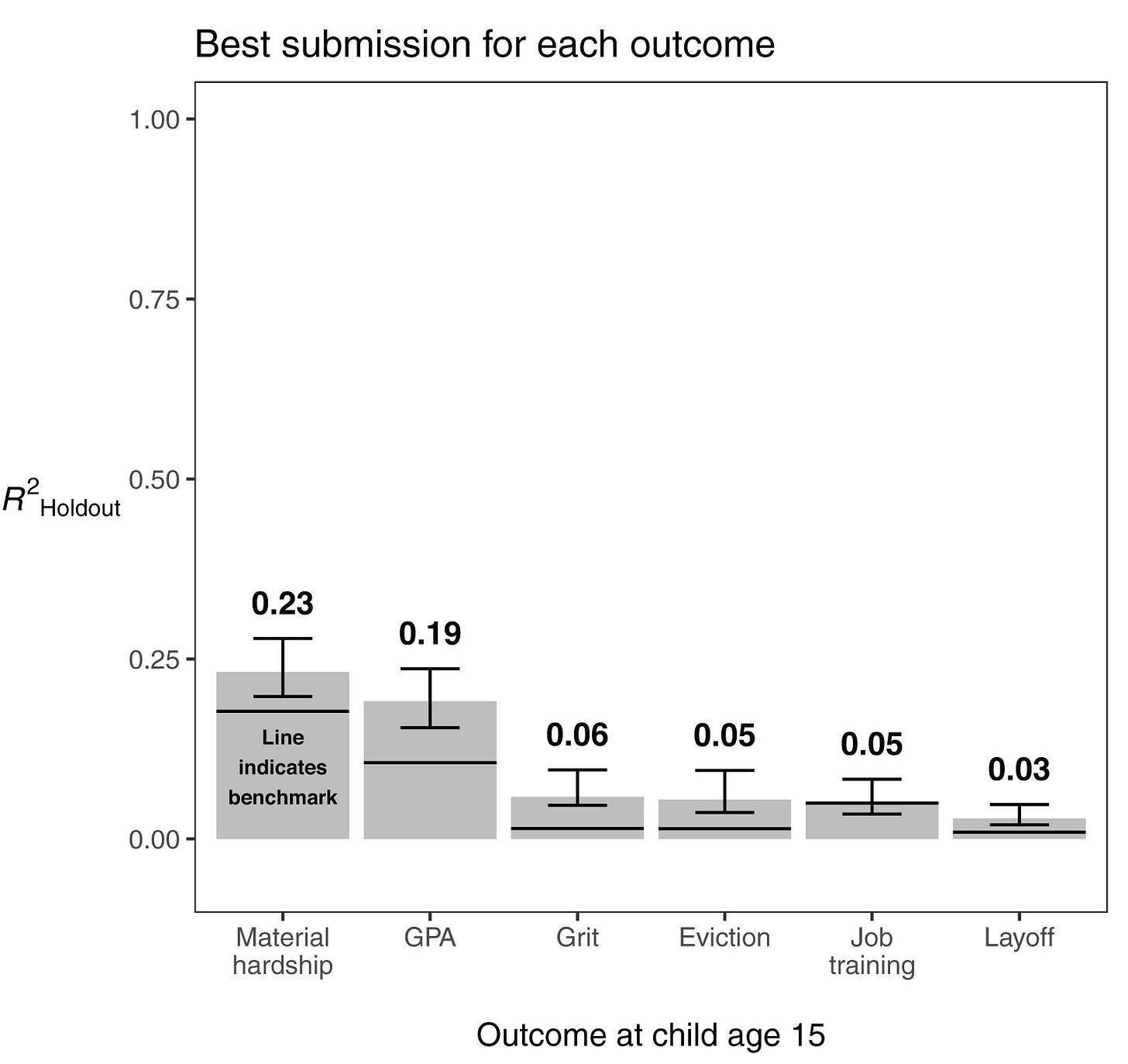

The Fragile Families Challenge tasked 160 different teams of researchers with producing the best possible models to predict six different outcomes for kids aged fifteen, using data gathered between birth and nine years of age.

The outcomes researchers were tasked with predicting were child GPAs and grit, household eviction, material hardship, primary caregiver layoff, and primary caregiver job training participation. The number of variables was substantial, the sample was reasonably large, and all the researchers had to do was at least beat a simple benchmark model based on linear or logistic regression with four expert-selected variables out of the nearly 13,000 available to participants: child’s race, parental marital status and education, and a measure or proxy of the predicted variable from age nine.

The best models in the bunch were marginal improvements over the benchmark model.

The end result here is just no good for ‘marshmallow theory’. The best model was for predicting material hardship and it only amounted to something like a correlation of 0.48—not unimpressive, but nothing to brag about. If this is as good as we can get from competitive efforts to make the best predictive models, then the hopes of predicting substantive life outcomes with singular behaviors like those observed in the course of the marshmallow experiment are just not there and we shouldn’t get our hopes up.

The world might be too complex for social psychology to offer actionable insights

If it seems like someone was trying to tell a story and they came up with an experiment that did, it’s probably fake. If a set of findings matched up too perfectly with received wisdom or popular-but-unsupported beliefs, then it’s not too much of a stretch to think someone wanted it that way, and found a way to show it. That is—unfortunately—much of what classic social psychology amounted to.

Milgram ‘showed’ that people will commit to horrors to go along with authority; Zimbardo ‘showed’ that giving people authority will result in horrors; Rosenhan ‘showed’ that psychiatry had produced horrible, abusive institutions; Sherif ‘showed’ that tribalism inevitably results in horrors; Asch ‘showed’ that minds can be warped into committing avoidable errors through group-think.4

All of these examples featured researchers who profited immensely from their work, and they seemed to show that humans are extraordinarily socially malleable, that people ultimately lack moral stability and agency, and that it’s an inconceivable miracle that we’ve ended up with the peaceful, prosperous society we live in. But that isn’t the case; at best, what we’ve been given is political wish-casting, and the methods and reputation of social psychology were laundered to that end.

The era of simple stories and powerful, flashy univariate predictions that make researchers popular successes should be behind us, and the simpler and more important someone tries to make a social psychological finding seem, the less we should believe it.

Where social psychology has been used to portray humans as dumb pieces of clay to be molded, it’s probably wrong. Where social psychology has been used to unduly indict groups that researchers dislike, it’s probably wrong. Where social psychology has been used to provide convenient experimental confirmation of bits of popular wisdom (“power corrupts”, “evil is banal”, etc.), it’s probably wrong. Where social psychology has been used to contraindicate views researchers call “narratives” but which are really ‘views researchers dislike’, it’s probably wrong. Where social psychology has been used to affirm the singular importance of small, unreliable aspects of human behavior, it’s probably wrong.

Much of social psychology has been guided by the desires of researchers to affirm this or that, rather than to discover things, but to fully come into its own, it should stop putting the cart before the horse. And maybe that means making the field unpopular.

Some of the findings mentioned in this piece were predetermined by motivated researchers looking to confirm something popularly believed and to make a name in doing so. If it wasn’t possible to abuse the field to do those sorts of studies popularly, or if it was impossible to make a killing doing it, then maybe so much fraud wouldn’t have happened. So maybe what social psychology needs to make it a field that helps us understand the complexities of the social world is for its researchers to be cordoned away from it.5

Later investigations have revealed that the debriefings were often too short.

Frankly, I think the belief that evil is banal is also uncalled for, but we can leave it where it is—unsupported.

Levari et al.’s work with prevalence-induced concept change in human judgments seems relevant and worth mentioning here, but it is, instead, about a problem of individual psychology.

One thing these examples also showed is that the replication crisis for classical findings that appear prominently in textbooks has a major element of fraud to it. The issues with those studies were not simply questionable research practices, but were instead fabrication, intentional omission, and other forms of deceptive behavior on the parts of researchers.

It might be wise to consider there to be two replication crises: one of fraud and one of bad science and publication incentives. There’s also a strong case for not splitting though. Take Francesca Gino’s fraudulent research. It inspired lots of often very expensive replication studies, extensions, model development, and wasted brainpower more generally, most of which turned up fruitless, but was honestly undertaken by independent researchers. The fraudulent studies clearly created honestly conducted studies that were bad because they were conducted due to previous fraudulent work, and no doubt there were studies that affirmed Gino’s fraudulent work by chance and got published because they had significant results or what-have-you.

Postscript: The title of this piece refers to the field’s classical findings. There’s plenty of work ongoing in the field, but I still question whether much of it merits consideration given the field’s general lack of theory development, coherent testing, and other issues that have been discussed amply elsewhere.

The original Marshmallow Test in Trinidad was a test of racial stereotypes. Walter Mischel wrote:

I spent one summer living near a small village in the southern tip of Trinidad.

The inhabitants in this part of the island were of either African or East Indian descent, their ancestors having arrived as either slaves or indentured servants. Each group lived peacefully in its own enclave, on different sides of the same long dirt road that divided their homes.… I discovered a recurrent theme in how they characterized each other. According to the East Indians, the Africans were just pleasure-bent, impulsive, and eager to have a good time and live in the moment, while never planning or thinking ahead about the future. The Africans saw their East Indian neighbors as always working and slaving for the future, stuffing their money under the mattress without ever enjoying life”

“To check if the perceptions about the differences between the ethnic groups were accurate, I walked down the long dirt road to the local school, which was attended by children from both groups.” “I tested boys and girls between the ages of 11 and 14. I asked the children who lived in their home, gauged their trust that promises made would be promises kept, and assessed their achievement motivation, social responsibility, and intelligence. At the end of each of these sessions, I gave them choices between little treats: either one tiny chocolate that they could have immediately or a much bigger one that they could get the following week”

“The young adolescents in Trinidad who most frequently chose the immediate smaller rewards, in contrast to those who chose the delayed larger ones, were more often in trouble and, in the language of the time, judged to be “juvenile delinquents.” Consistently, they were seen as less socially responsible, and they had often already had serious issues with authorities and the police. They also scored much lower on a standard test of achievement motivation and showed less ambition in the goals they had for themselves for the future.

Consistent with the stereotypes I heard from their parents, the African Trinidadian kids generally preferred the immediate rewards, and those from East Indian families chose the delayed ones much more often. But surely there was more to the story. Perhaps those who came from homes with absent fathers—a common occurrence at that time in the African families in Trinidad, while very rare for the East Indians—had fewer experiences with men who kept their promises. If so, they would have less trust that the stranger—me—would ever really show up later with the promised delayed reward. There’s no good reason for anyone to forgo the “now” unless there is trust that the “later” will materialize. In fact, when I compared the two ethnic groups by looking only at children who had a man living in the household, the differences between the groups disappeared.”

https://www.unz.com/isteve/the-origin-of-the-marshmallow-test/

Informative and fascinating. What stands out to me about this article is how the researchers seem to uniformly seek confirmation of beastliness in human nature. A couple of years back, it dawned on me that The Lord of the Flies was bullshit in its depiction of British, Christian boys descending into tribalism and savagery. Maybe it's a narrative that found its way into the worldview of researchers, despite a plenitude of counterexamples involving European, Christian folk who go into savage places and turn them into admirable civilizations. Somehow, they possessed the character to bring order into the wild instead of allowing the wild to overcome their character. Perhaps the social scientists should investigate the interesting phenomena of human fortitude, cooperation, and vision.