Tylenol and Autism: A Replication!

A Japanese sibling control study, probabilistic sensitivity analysis, and negative control study all-in-one paper confirms there's no link!

Last week, I reviewed a recent systematic review cited by the HHS in support of their argument that Tylenol (acetaminophen/paracetamol/APAP) is a factor involved in causing autism. That report was not credible; in fact, it was internally contradictory and its authors eschewed causal thinking and showed that they had a poor understanding of epidemiological methods. For more detail, go read my review of it:

Or, if you prefer a short-and-sweet rebuttal, go check out the earlier article I wrote on the topic:

If you would just like to understand the “autism epidemic”, as it were, then go see:

And finally, if you want to see how to end the “autism epidemic”, check out:

As luck would have it, more evidence has come out since that systematic review was published. This new evidence came online at the beginning of September and evidently everyone missed it, but it is considerable. Given what we already know—it is highly unlikely that acetaminophen has any role in autism—, it’s nothing new: it reinforces the knowledge that acetaminophen does not cause autism!

Japanese Evidence

The new study is a tour de force.

The new study takes place in Japan, far afield from the northern European countries all of the previously available causal evidence ultimately comes from. The authors’ dataset is a national administrative database linking mothers and their offspring between April 2005 and March 2022. This database contains data on a total of 16 million people covered by the Society-Managed Health Insurance System, including employees of medium-to-large companies in urban areas and their dependents. Overall, the database contains a representative slice of 13% of Japan’s total population.

The study ended up with a sample of 182,830 mothers who gave births, with a total sample of 217,602 of the resulting children. Usage of acetaminophen during pregnancy was identified from prescription dispensation records. Although acetaminophen is available over-the-counter in Japan, most usage comes from prescriptions1, and usage during pregnancy is generally found to be uncommon. The authors used any usage during pregnancy as their exposure measure and they used ADHD, autism, and intellectual disability diagnoses or corresponding treatment records as their outcomes.

These authors had a lot more covariates available to them than previous authors did. They had data on covariates ranging from maternal birth order to the results of her most recent health checkup to a wide array of different drugs they’ve used at various points in time. They used this data to do basic adjustments, to do stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), and to do propensity-score matching (PSM). Stated differently, they had more controls and better control strategies than many other papers.

The authors were also able to do three other important things related to the wonderful data they had available to them. The authors were able to computed bounding factors to assess the strength of possible selection bias required to explain their results. They were able to use their PSM approach to calculate E-values, indications of the minimum strength an unmeasured confounder needs to have to explain their observed results. They were able to also do a negative control analysis using drug usage data from before, during, and after pregnancy. Finally, they were able to assess the effect of misclassification in a probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Baseline Results

Maternal acetaminophen usage was related to teach outcome before any adjustments were made. Usage predicted a 34% greater crude risk of ADHD, a 17% greater risk of autism, and a 20% greater risk of intellectual disability—all highly statistically significant results.

Adjusted Results

After basic covariate adjustment, the results for ADHD and autism remained statistically significant, but were reduced to 22% and 8% increased risk. The result for intellectual disability dropped to 5% greater risk, but was no longer anywhere near significant.

PSM and IPTW

The PSM and IPTW results were directionally comparable to the crude and adjusted results, but significance was mixed. For the IPTW results, ADHD risk remained elevated by 32% and autism risk was marginally significantly elevated by 9%, whereas intellectual disability was not significantly elevated (+3%). For the PSM results, ADHD risk remained elevated by 22%, but the other results were rendered nonsignificant: +7% for autism and +3% for intellectual disability.

Confounders and Selection

The strengths of confounding and selection bias required to explain these results were pitifully small. The E-value computed for an overall composite neurodevelopmental outcome (+19% at baseline, +8% in PSM) based on the three diagnoses was an HR of 1.37, and the bounding factor required to explain the result for the same outcome (+9% in IPTW, +11% in IPCW) was 1.24. In the authors’ words:

an unmeasured confounder associated with both the exposure and outcome by a risk ratio of at least 1.37 could explain away the observed effect.

and

if the selection mechanism related to pregnancy loss were associated with both the maternal acetaminophen use and the composite outcome with risk ratios of approximately 1.24 each, the true association could be entirely attributable to bias.

To put these in perspective, translate them to correlations. HRs of 1.37 and 1.24 are on the order of Pearson correlations of 0.06 to 0.09. Very minimal biasing factors could explain these results, which are not unlike other published results in the systematic review, as we saw when I looked into it last time.

Negative Controls

Using NSAIDs or aspirin was associated with +8% or a nonsignificant +14% boost to composite neurodevelopmental risk. For acetaminophen use before pregnancy, there was a significant negative association with risk, -7%, whereas usage after pregnancy was marginally nonsignificantly associated with elevated risk, +5%.

In a previous study—which I’ve already discussed—done on the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort, acetaminophen usage before and after pregnancy were not significantly associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes, but they were directionally associated with elevated risk consistently before pregnancy and inconsistently after pregnancy, but always nonsignificantly. The association during pregnancy was directionally consistent, but sometimes nonsignificant or marginally significant.

In the Norwegian and Mother Child Cohort, usage before pregnancy was associated with marginally significantly elevated risk of communication problems, and no association with externalizing or internalizing symptoms. This risk elevation (+19%) was similar to the risk elevation for acetaminophen usage during all three trimesters (+18%), which was itself nonsignificant. In the Ahlqvist et al. study, there were no significant negative control associations except for one with aspirin use in their sibling comparison.

All of these results do not agree: “NSAIDs and aspirin use during pregnancy and acetaminophen use after pregnancy indicated the presence of bias away from the null, whereas acetaminophen use before pregnancy indicates the bias towards the null… These findings highlight the inherent limitations of negative control analyses, as there is no definitive standard, and the detected biases may not fully capture the true underlying bias structure.”

Frankly, it’s hard to take negative control results seriously in general because, as Ahlqvist et al. noticed, mothers move away from taking medications during pregnancy. That’s the smart thing to do, and it’s something we should expect to be selective, much as phenomena like SIDS and childhood obesity are selective with respect to parent knowledge and conscientiousness. The idea behind these analyses is that the bias structure will be shared before and during or during and after, or before, during, and after pregnancy, and this is just not realistic in a world where mothers shift their habits selectively when they become parents.

Misclassification Assessment

Finally, these authors found something I suggested was possible when I last wrote about this topic: that misclassification of acetaminophen use could bias results upwards. They note:

Our probabilistic bias analysis indicated that misclassification of acetaminophen exposure, particularly owing to unrecorded OTC use, may have led to an overestimation of the observed associations. This bias is reflected in the consistent attenuation of effect estimates towards the null across a range of plausible levels of OTC use. Although OTC use among pregnant women in Japan is generally low, our findings indicate that even minor misclassifications could partly explain the modest associations observed. Moreover, this limitation is not unique to prescription-based data; exposure misclassification can similarly occur in studies relying on self-reported data, where recall errors or underreporting may further obscure the true exposure status.

Wrapping Everything Together

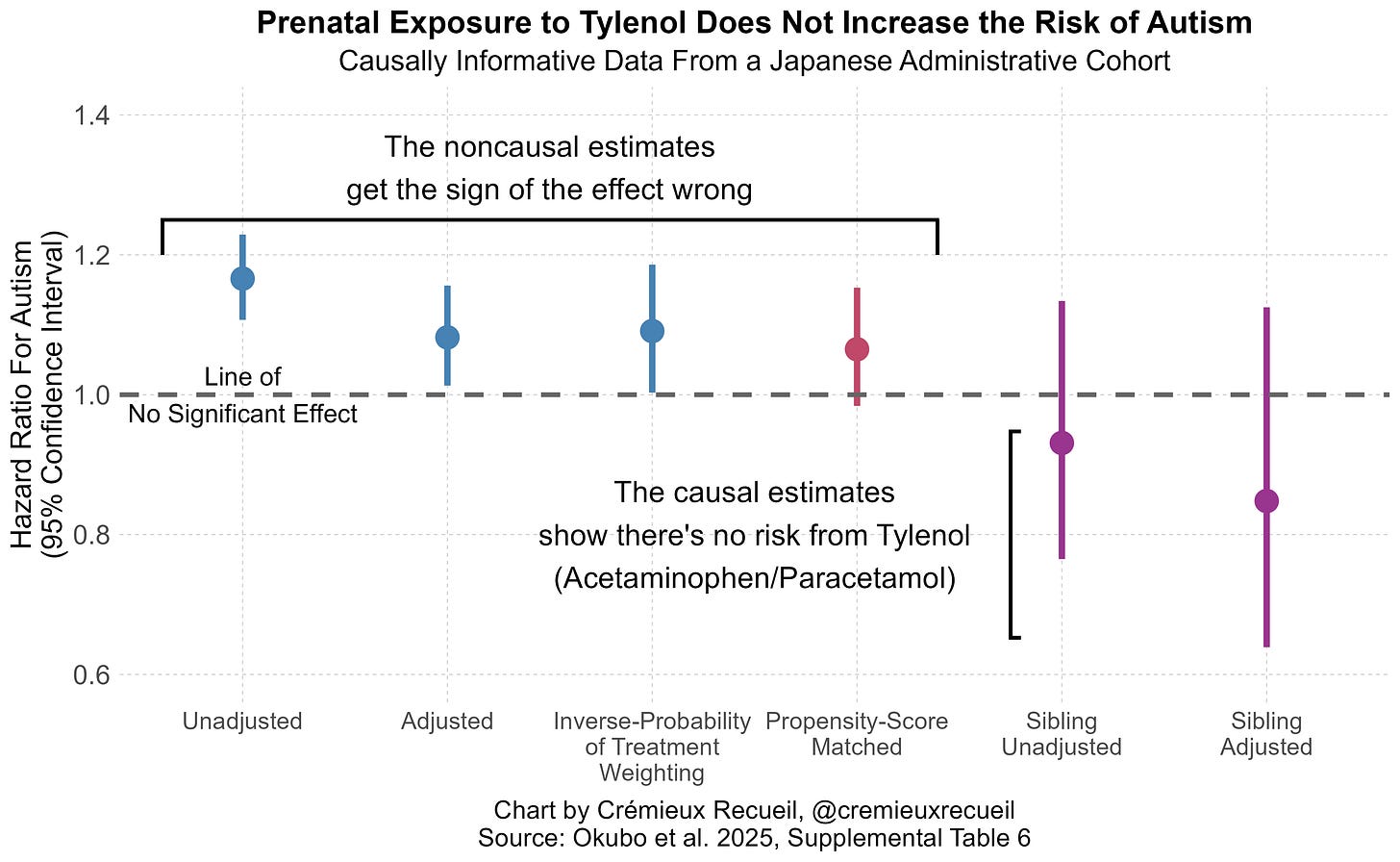

The results of these methods are in agreement: there’s not much evidence for acetaminophen risk, using the best non-causal methods cited in the systematic review, with a large, representative sample. But the authors didn’t stop there. They went on to replicate Ahlqvist et al.’s sibling control results in a sample with 23,593 children with discordant acetaminophen exposure! Their replication was fairly exact, too. Where Ahlqvist et al. saw the direction of risk nonsignificantly reverse, so did these authors. Give the results a look:

Notice the presence of two sibling estimates. One of those is not adjusted for other covariates and the other is adjusted for them, and they agree with one another.

Ergo, there we have it! Every line of defense for the prior literature, and every reason cited to dismiss Ahlqvist et al. fails. Both their significant cross-sectional effect and their directionally opposite, nonsignificant sibling control results replicated outside of Sweden, in distant, high base rate, Japan; misclassification issues likely pushed results in the wrong direction for the literature to support an acetaminophen-autism link, and; the sibling result was not attributable to prior covariate adjustments.

Professional societies have responded appropriately to HHS’ announcement about the link between acetaminophen and autism, by rejecting it. With luck, providers will heed that advice and eventually the U.S. government will follow suit. That is how things should be, and this new causal evidence supplies us with ample reason to think the field’s earlier conclusions were correct: acetaminophen does not cause autism.

October 8 2025 Update: Organoids!

The FDA has recently made calls for more organoid-based drug evaluations. An organoid is, simply, a 3D miniaturized organ-like structure grown in vitro using stem cells, in order to mimic the structure, function, and development of human organs, for study. One of the goals of shifting towards organoid-based testing is to reduce the amount of animal cruelty involved in producing preclinical safety and efficacy data. If the FDA succeeds, it will have genuinely made medicine a less cruel enterprise. That is laudable.

A group of researchers at UC San Diego has taken the FDA up on this call for more organoid-based research and tested whether reasonable doses of acetaminophen can plausibly affect neural development. Their efforts are impressive and their results are important, so let’s review.

Firstly, what exactly does doing organoid research offer us here? Think about how inconsistent this literature is.

In what trimesters is fever related to autism risk? Primarily the second, and possibly the first (though it seems unlikely this is causal). When does acetaminophen usage during pregnancy have its largest correlations with autism? In the Japanese study above, the answer was the third trimester, with no risk elevation for ASD, ADHD, or intellectual disability in trimesters 1-2; in the fraudulent review, their answer was 2-3. This should immediately set off alarm bells, since acetaminophen is the treatment for fever!

In what trimester do we get the commonly-noted autism-related neuronal wiring issues? The third and after birth, with other more transient changes happening earlier on.2 System-level analyses of autism risk genes show convergence in deep-layer cortical projection neurons during the mid-fetal period. Prenatal brain growth associated with autism may be detectable by ultrasound starting at 20 weeks (also MRI!)—in the second trimester. With less crude methods, we’d likely see distinguishing development earlier, but in any case, we see developments that are more or less critical to autism happening all over the place and a mixture of in- and out-of-line with supposedly elevated exposure-related risks.

These findings overlap, but not reliably. The unreliability suggests our signals for autism are muddled and clarifying tools would be nice to have.

Organoids could be just such a clarifying tool, and they wouldn’t force us to rely on non-human evidence or tenuous chains of mechanistic reasoning. As the authors of this new organoid study succinctly noted: “Animal studies have raised additional concerns, reporting long-term behavioral and synaptic changes after developmental APAP exposure, with proposed mechanisms including oxidative stress, apoptosis, and endocannabinoid disruption. Yet many of these studies used supra-therapeutic doses, and species differences in brain development complicate translation.”

Organoid studies let us test all of these possibilities in a human model!3

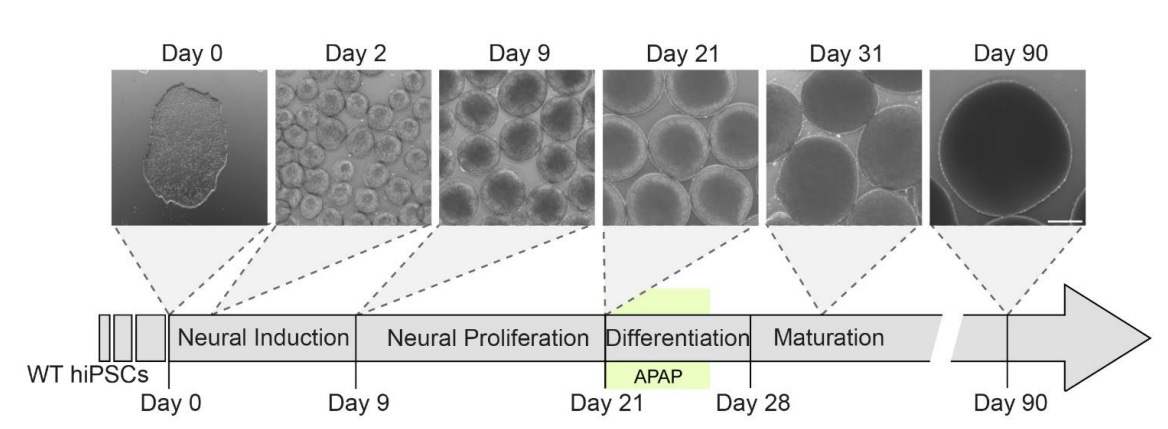

These authors used human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical organoids, which are able to model fetal development and have already been successfully put to that purpose for modeling the effects of genetic variations and alcohol and pesticide exposures. After getting everything set up for a physiologically-relevant test of the effects of acetaminophen exposure during fetal development, they hit the cells with it around twenty-one days in. Here’s the timeline:

The dosages selected by the authors were extremely reasonable. The authors used data from in silico models of acetaminophen exposure across the umbilical cord which provided an estimated mean fetal arterial drug concentration of 25 μM, and they put that as their lowest dosage. They went up to 100 μM because in vivo studies of adults found that to be the peak maternal plasma concentration. This means that they’re exposing the organoids to doses that range from obviously physiologically-relevant (typical, at least the mean) to extreme but possible (peak).

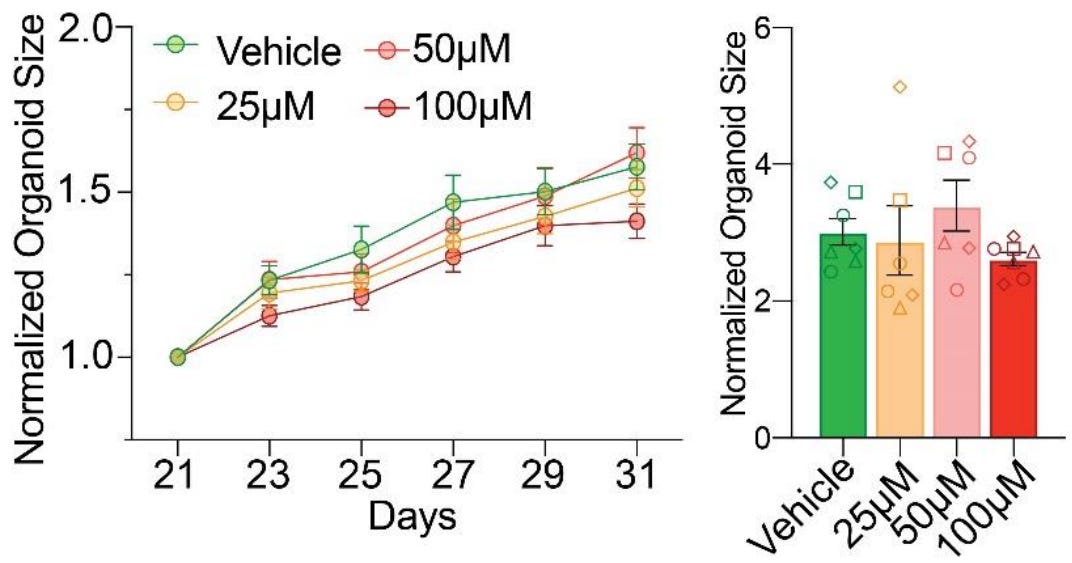

First finding: acetaminophen does not effect abnormal growth trajectories. This is pretty simple. Organoids displayed “remarkably consistent growth patterns” across all dosages during exposure (left) and reached practically identical, statistically indistinguishable organoid sizes three months out (right).

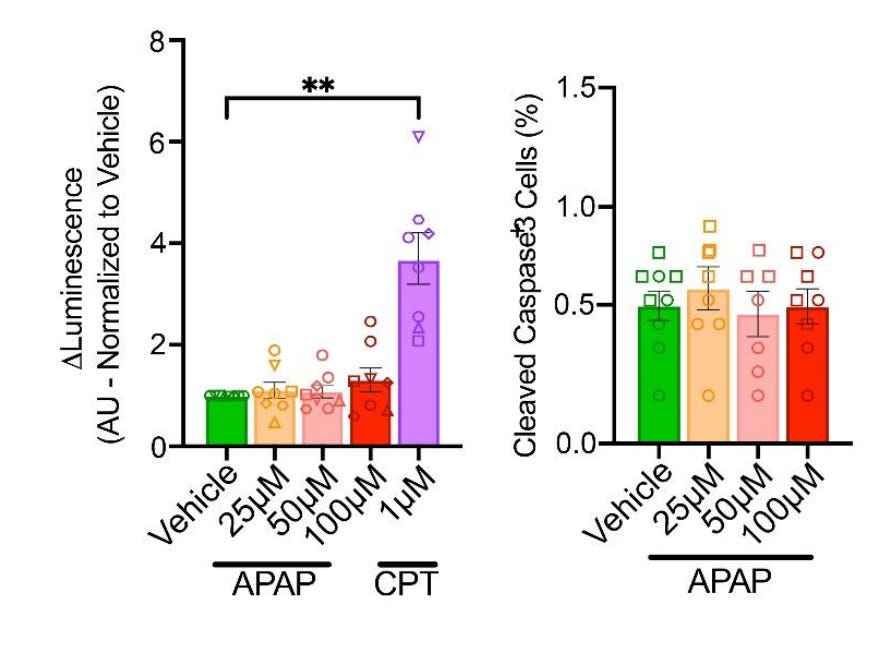

Second finding: acetaminophen does not cause cytotoxicity. This is less simple. The authors assessed this possibility in two complementary ways.

The first cytotoxicity assessment (left) was done by measuring caspase 3/7 activity via luminescence assays five days after initial exposure, after the exposure on day 26. Caspase 3/7 activity is a marker for apoptosis, which is one of the mechanisms by which acetaminophen has been proposed to disrupt neural development. The authors compared acetaminophen’s effects on caspase 3/7 activity to the effect of camptothecin (CPT), which is well-known to cause apoptosis. Unlike acetaminophen, CPT did cause apoptosis.

The second method (right) was to stain organoid slices for caspase-3, which is another apoptosis marker. The authors found that apoptotic cells were less than 1% of the total cell population and there were no statistically significant differences in apoptotic proportions between acetaminophen-treated slices and control slices.

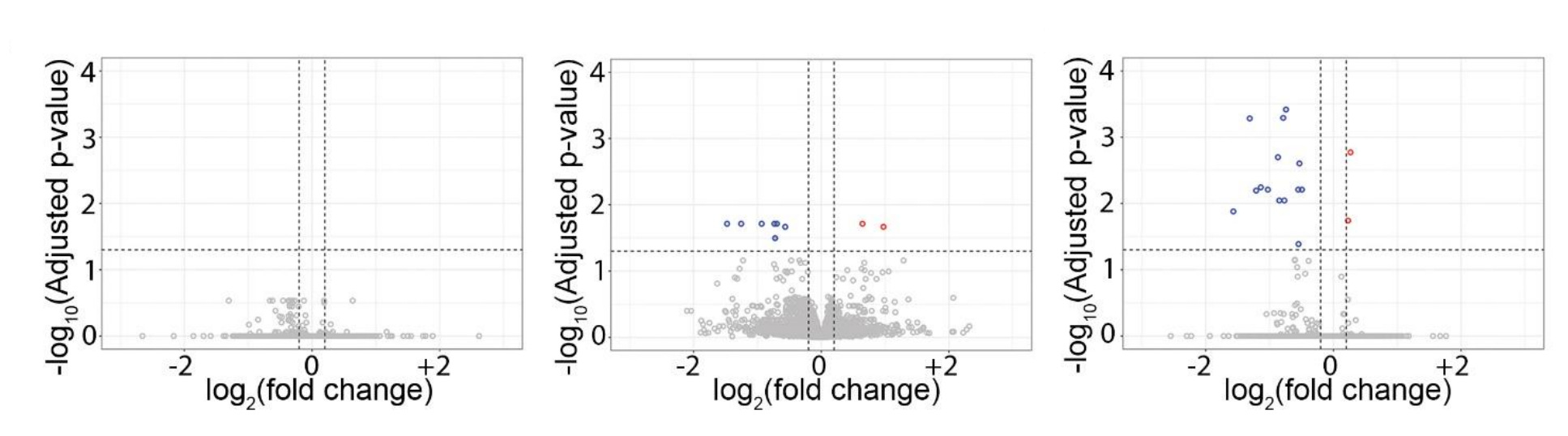

Third finding: acetaminophen exposure impacts the expression of a small number of genes, but does not disrupt transcriptional architecture or gene co-regulation patterns. The authors found enrichment on a few genes at double the average dosage (i.e., 50 μM, middle) and at four-times the average dosage (100 μM, right), but these were absent at typical exposure (25 μM, left) and inconsistent between 50 and 100 μM. Because there was no consistent dose-related pattern to this result, it’s doubtful expression changes were meaningful. This inference is supported by the next finding.

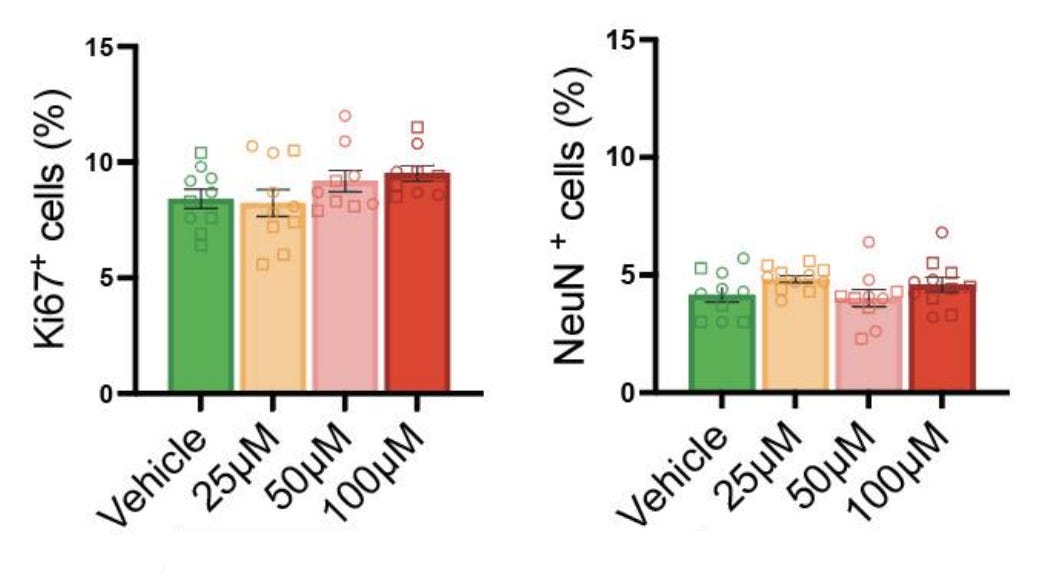

Fourth finding: acetaminophen exposure does not effect changes in the balance between neural progenitors and mature neurons. The authors found that a proliferative progenitor marker (Ki67) and a neuronal marker (NeuN) were found in the same proportions in exposed and unexposed organoids, so neuronal differentiation was unaffected.

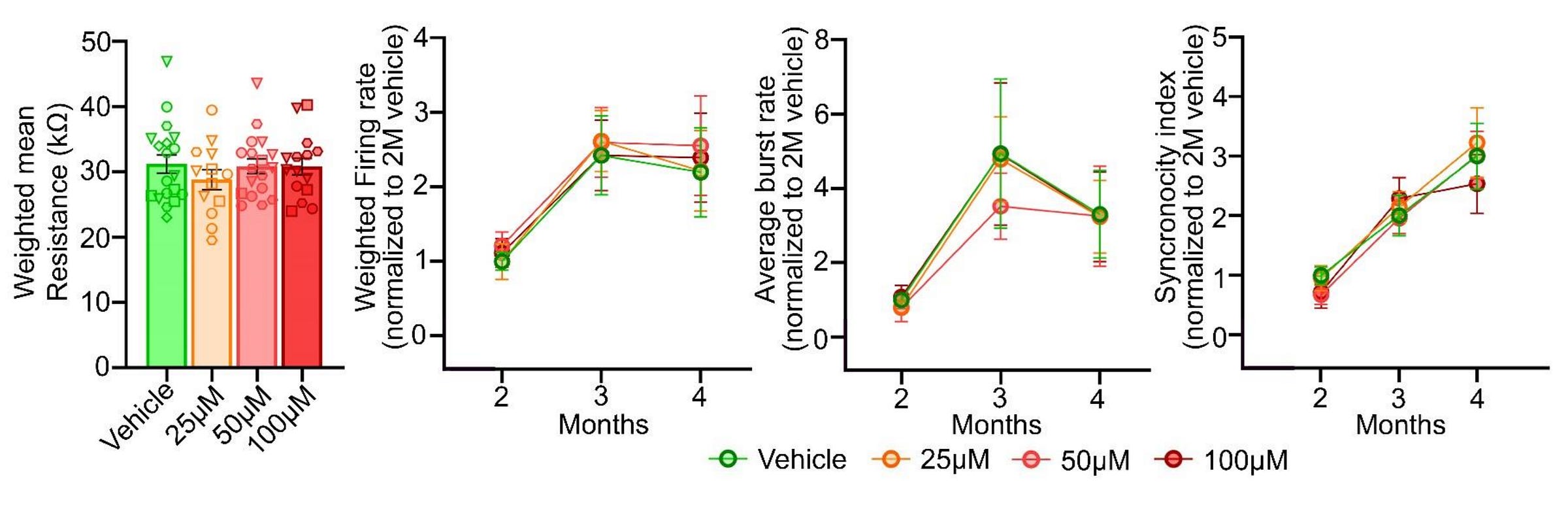

Fifth finding: acetaminophen exposure does not affect electrophysiological properties or connectivity. Exposure to acetaminophen didn’t alter resistivity at four months and it didn’t affect the development or end results for the firing rate, burst generation, or coordination of firing across electrodes.

In organoids, acetaminophen exposure does not affect cytoarchitecture, does not induce apoptosis, does not affect transcriptional architectures or gene co-regulation patterns, does not affect progenitor or mature neuron proportions, and does not affect anything to do with the electrical properties of neurons. Autism is related to all of these things. This result is, thus, in agreement with sibling-controlled results, Mendelian randomization, and an event-study from Denmark, placing it squarely alongside all other causal evidence. Because this method is able to ascertain causal effects in agreement with these epidemiological and econometric methods for other exposure types, it seems doubtful this result was due to the methods being insensitive.

My interpretation of these results is that this this signals acetaminophen exposure genuinely doesn’t directly do what it should do were it a potential cause of autism. Acetaminophen certainly does not operate on at least two of the mechanistic pathways that have been so far proposed to explain a connection with autism: not oxidative stress and not apoptosis.

To save the acetaminophen-autism connection now, there would need to be extensive downstream interactions, and adding an interaction effect to save a theory naturally means a conjunction penalty and a more fragile hypothesis. Thankfully, the other causal results already make it clear: we don’t have to think about more expansive explanations, because there’s not any reason to think there’s a causal effect to explain!4

Japan’s 2024 OTC analgesics market was valued at $350.1M. A representative OTC APAP price from Daiichi Sankyo’s new Calonal-A (300 mg) is 36 tabs for ¥1,518 → ¥42.2/tab → ¥140.6 per gram of APAP. Set $1 to ¥150, that’s ~$0.94 per gram. Japan’s largest APAP brand, Ayumi, ramped up production of prescription Calonal (not Calonal-A) to 2.88 billion 200mg equivalent tablets per year, or 576 metric tons of API capacity per year and they’re responsible for 85-90% of prescription acetaminophen in Japan. Convert OTC APAP value to grams using the retail price-per-gram, as (OTC analgesics market * APAP share)/($/g) and if APAP is 30%, of OTC analgesics versus an assumed 500 metric ton Rx share, you get that 18% is OTC. If it’s half of the OTC analgesics market, you get 27%. If it’s 70%, then you get 34%.

With reasonable assumptions, the majority of acetaminophen in Japan must be prescription.

As I’ve noted before, animal-based results often totally fail to generalize to humans. Here are some examples:

Dozens of agents that looked great in rodent stroke models crashed in human trials.

Anti-TNF strategies and numerous other sepsis targets have repeatedly failed in humans RCTs despite incredibly encouraging mouse data. Some authors have suggested that this could be due to mismatched inflammatory responses. Other authors replied that gene expression patterns are similar between humans and mice if we subset to those genes showing significant changes in both humans and mice, but there are a few obvious problems with this. Namely, there’s ascertainment, but more importantly, their measure of agreement was sign agreement with correlations between 0.43 and 0.68, which aren’t altogether great, and come with large disagreements in magnitudes. I think the translational failure records speaks for itself.

In 2006, a CD28-specific monoclonal antibody looked promising for the treatment of cancer. But its usage led to a massive cytokine storm in humans. Clearly, the non-human primate toxicity studies that preceded human usage had failed. But why? As it turns out, cynomolgus monkeys lack activity for the target molecule on their T-cells.

Fialuridine was once considered a promising target for treating hepatitis B infections. It looked great preclinically, and it was clearly safe enough for humans by traditional metrics. But when it came time for clinical testing, five out of fifteen patients ended up dead from liver failure and another two had to have liver transplants. Several animal models failed to predict these effects, and the only suitable ‘off the shelf’ model turned out to be woodchucks. It took some pretty special mice to detect this issue.

Thalidomide’s profound limb defects observed in humans were not reproduced in common lab species under similar conditions, and sensitivity to the drug varies sharply across species and strains. Relatedly, as I noted in that earlier article, some things cause and some things cure cancer in other species with no corresponding effects for us humans.

The repeated successes treating Alzheimer’s disease in APP/PSA1-type mouse models failed to translate to human benefits across numerous trials.

There are even many examples of species-specific drug-drug interaction behaviors. For example, rifampin—a potent inducer of human CYP3A via human PXR—has little effect in mice. Mice instead respond strongly to PCN—a rodent-specific PXR agonist that does not activate human PXR. So, drug-drug interactions observed in PCN-treated mice via PXR induction don’t occur in humans and, conversely, rifampin-triggered drug-drug interactions in humans won’t show up in normal mice. Researchers consider this so well-established that they use PXR-humanized mice to model human drug-drug interactions! Here’s a relevant citation on acetaminophen toxicity.

In short, we need to be generally skeptical that animal model results will translate to humans. They usually do not. In fact, stated more strongly, virtually all drugs have what appears to be strong preclinical safety and efficacy evidence, and yet the overwhelming majority fail when it comes time to put them through human clinical trials. Remembering this fact will help to avoid confused mechanistic reasoning based on animal models.

Whether the reason is pathophysiology mismatches, immune/cell surface biology differences, ADME and regulatory receptor differences, or something about genetics, timing for teratology, or whatever else, animals are not humans. And anything I’ve said about animal evidence being insufficient applies multiple times more to purely mechanistic reasoning, which is generally even more tenuous since it relies on complicated chains of events taking place, when they have usually not been reliably demonstrated to do so. This type of evidence also nearly always fails to translate into clinical success.

You can reason to this conclusion pretty easily just by noticing all the trial failures and the times when mechanistic reasoning predicts an epidemiological finding and that doesn’t happen, but if you’re having trouble, think through these:

Pathways are often redundant and homeostatic; block A and B and C can compensate. A mechanism that’s there in vitro or at supraphysiological doses can vanish or reverse at human tissue levels, a different pH, oxygen tension, redox state, or protein binding. Absorption, first-pass metabolism, distribution into relevant compartments, receptor occupancy over time, and active metabolites dominate medical outcomes and perfect inhibitors that never reach the site of action don’t help patients. Small upstream nudges can be buffered, small downstream nudges can cascade, and additive expectations can fail (e.g., two QT-prolongers can give more or less than their sum depending on heart rate, electrolytes, autonomic tone, etc.). Fixing a biomarker (PVCs, HDL, amyloid plaques, CRP, tumor shrinkage, etc.) doesn’t guarantee improved survival or function, and surrogates may be correlated with—or even defined based on!—disease, but not actually indicative of being treated. Great target engagement for a target that isn’t actually on the causal path for a clinical endpoint in humans is common (sometimes you even have different drives in treated subgroups; disease heterogeneity is not fun!). Off-target effects, immune modulation, drug-drug and drug-microbiome interactions can erase benefits or create net harm from medicines when they reach clinical evaluation. Average mechanistic stories rarely match patient genetic differences, comorbidities, comedications, age, sex, environments, care pathways, etc., and true effects can be narrow-band and disappear in heterogeneous populations. Acute and chronic dosing, circadian biology, disease stage, and treatment timing can change results and a drug that helps at some point might hurt at another or vice-versa. Regression to the mean, confounding by indication, immortal time bias, publication bias, and flexible analyses (“researcher degrees of freedom”) often inflate perceived mechanistic success probabilities before trials fix the noise (consider the fraudulent Italian GMO studies or the too-limited Italian glyphosate mouse studies).

We have lots of examples here. Antiarrhythmics, for example, successfully suppressed ventricular ectopy (mechanism), yet increased mortality. HDL-raising drugs significantly raise HDL, but provide zero cardiovascular benefits because HDL elevation wasn’t a causal lever. Antioxidants have an obvious redox rationale, but they offer no prevention benefit, possibly harm in smokers, and, as Derek Lowe has been saying for years, they might even be more broadly harmful. Protein binding drug-drug interactions predict big free-drug spikes, but in vivo clearance adjusts within minutes and net effects are usually trivial. Lots of cancer-targeted agents have great IC₅₀s, but deliver zero clinical impact when tumors use bypass mechanisms or evolve resistance.

Attempting to ‘logic’ to some conclusion through mechanistic evidence often sounds like ‘It chelates X, so it will…’ when ligands outcompete this, and distribution barriers prevent meaningful complex formation in vivo. Frankly, to me, mechanistic reasoning is often just being ‘lab-brained’. You cannot use Henderson-Hasselbalch intuitions in tissues; receptor occupancy doesn’t translate to efficacy because of biased downstream signaling, desensitized or scaffolded by different isoforms; and many toxicities are nonlinear. And we so rarely know how to deal with any of this, so mechanistic reasoning is just yammering. In fact, it’s so bad that, even though we know it works, we don’t even know the mechanisms behind acetaminophen! (Which reminds me of some of my favorite papers on ‘mechanisms’ and the apparently Millian take that causal empiricism should be about identifying the effects of causes rather than the causes of effects.)

If people want me to take mechanistic reasoning seriously, they should:

Show that moving chemical/biological targets causally moves the patient-relevant outcome rather than some biomarker or whatever lab value.

Verify unbound concentrations at the site of action over time match those needed for effect.

Replicate across models that vary the compensatory circuits and show effects survive plausible co-medications, comorbid states, and physiologic ranges.

Prespecify subgroups heterogeneity should be found in based on competent causal reasoning and avoid garden-of-forking paths voyages.

Align evidence from orthogonal methods like Mendelian randomization, natural experiments, high-quality observational designs, and early randomized tests with hard outcomes or validated surrogates. (Like I’ve done with acetaminophen.)

Demonstrate monotonicity or theoretically expected dose-response and time-response curves in humans, not just in cells and animal models.

State what data would refute the mechanism or mechanistic story then actively try to break it, pursue data that shows it’s wrong, etc. One of my biggest gripes is that people do not comprehensively assess the evidence for or against mechanistic stories, preferring instead to just talk about how their story should work, even when existing evidence suggests it’s nonsensical.

And this is difficult, but model off-target pathways, transporter interactions, immune consequences, and microbiome effects that might be relevant, measure them prospectively.

Ultimately, we clearly do not even need mechanistic evidence for drugs to work and to understand at a ‘human level’ how they work (acetaminophen makes this incredibly clear), so these are really just standards for the people who, for some reason, insist on avoiding standard epidemiological tools and trials.

So say it with me: (practically) the only clinically-relevant evidence is clinical evidence!

To add on to Footnote 3, consider what the authors had to say about why their results differ from recent animal results. They wrote: “A key difference may lie in drug metabolism. In rodents, neurotoxicity has been attributed to the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), generated through cytochrome P450-mediated oxidation. However, in humans, fetal CYP2E1 expression is minimal until last gestation and increases primarily after birth, with detoxification in early development handled mainly by sulfation pathways. Because cortical organoids lack hepatic metabolism, our results likely reflect direct effects of the parent compound, approximating the in utero environment, where fetal exposure to NAPQI is negligible.”

In other words, the organoid approach is more realistic for two reasons: being directly human, and lacking a form of environmental interference. This is a predictable result based on the Mendelian randomization results I previously detailed.

Thanks for the conformation and clarification.

Oh god, Cremiuex, you get so into the statistical weeds here! I had a pretty solid education in basic social science stats, but it did not cover a number of things you talk about here: E-value, propensity weighting, probabilistic sensitivity analysis, negative control analysis,"stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting. I could look up each of these terms and follow your train of thought, but life's too short. I asked GPT to summarize your train of thought without the use of arcane statistical terms, and the result is here: https://chatgpt.com/share/68e5b82a-9be4-8008-81f5-a158ee07131a

The text of what it wrote is below. It also included a nice graph at the end of the decline of the estimate of autism risk from tylenol step by step, starting with the baseline results and declining step by step to 0 as you applied de-confounding stats one by one. You should maybe check the text to see whether you think it's correct. If it is, maybe consider including something like this if a post is very technical.

***************

1. Study Basics

Researchers in Japan studied over 180,000 mothers and more than 200,000 of their children.

They looked at whether acetaminophen (Tylenol) use during pregnancy was linked to later autism diagnoses in the children.

Acetaminophen use was identified from prescription records, which in Japan cover most use since pregnant women rarely take over-the-counter (OTC) medications.

2. Initial (“Crude”) Results

At first glance—without adjusting for anything—mothers who used Tylenol during pregnancy seemed more likely to have children later diagnosed with:

ADHD: +34% risk

Autism: +17% risk

Intellectual disability: +20% risk

All these differences were statistically significant at that first step.

3. Adjusting for Confounding Factors

Once the researchers took into account other differences between mothers who did and did not use Tylenol—such as their health history, medication habits, and pregnancy characteristics—the apparent effect shrank sharply:

Autism: only +8% increased risk, and still statistically significant but small.

In other words, after accounting for known background differences, most of the earlier apparent risk diminished.

4. Deeper Control Methods

The authors then applied two stronger statistical balancing methods:

Propensity-score matching (PSM)

This method pairs each Tylenol-using mother with a very similar non-user (same age, health profile, etc.), as if creating “twins” in different exposure groups.

Result: autism risk only +7%, not statistically significant.

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)

This technique gives more weight to people who are under-represented in either group so that, overall, the exposed and unexposed groups become balanced on all measured characteristics.

Result: autism risk +9%, barely significant.

So across these methods, the autism link kept weakening and usually lost statistical significance.

5. Checking Whether Small Biases Could Explain Everything

The authors then tested how strong any unmeasured confounding would have to be to create a false appearance of risk.

They found that:

Even a very small hidden bias (roughly a correlation of 0.06–0.09 between Tylenol use and autism) could fully explain the tiny remaining effect.

That means the apparent link could easily vanish if even a minor unnoticed factor (such as cautious mothers avoiding all drugs, or doctors’ differing prescribing habits) were accounted for.

6. “Negative Control” Checks

They compared autism risk when mothers used similar drugs:

Before pregnancy: Tylenol use was actually linked to lower autism risk (–7%).

After pregnancy: slightly higher risk (+5%), not significant.

Other pain relievers (NSAIDs, aspirin): small or inconsistent increases.

Because these patterns didn’t make biological sense (Tylenol before pregnancy couldn’t cause autism), they suggested that the remaining differences were due to bias, not causation—probably differences in which mothers take or avoid medications at various times.

7. Misclassification of Exposure

They also noted that many small errors in measuring Tylenol use could falsely inflate the apparent risk.

For instance, some pregnant women might take OTC Tylenol without it appearing in prescription data, blurring the line between “users” and “non-users.”

Simulations showed that even modest amounts of such misclassification would make the risk seem higher than it really is.

8. Sibling Comparisons

Finally, they compared siblings—children from the same mother, where one was exposed to Tylenol in utero and the other was not.

This design cancels out all family-level factors (genes, home environment).

Result: the autism link disappeared or reversed direction, confirming no real effect of Tylenol itself.

9. Overall Reasoning and Conclusion

All methods converged on the same picture:

Stage of Analysis Apparent Autism Risk Interpretation

Crude comparison +17% Looked risky, but unadjusted

Adjusted for basic factors +8% Small, borderline

Matched/weighted samples +7–9% Not statistically significant

Sibling comparison 0% or reversed No causal link

Because:

even tiny hidden biases could erase the effect,

results were inconsistent across timing and control drugs,

and sibling comparisons showed nothing,

the author concludes that Tylenol use during pregnancy does not increase autism risk at all—and earlier studies suggesting otherwise were probably misled by small biases and measurement errors.