Wanted: More Maternal Health Research

We know much less than we ought to about the role of maternal health in child outcomes.

In 2024, I want to see more research on the womb. More specifically, I want to see more research on how maternal health, behaviors, and decisions impact the outcomes of their children. This domain is incredibly important, and yet so many research projects within it seem to crash and burn, and sometimes they gain a massive audience only to fizzle out.

If what I’ve said is true, it’s a problem.

I believe me, and I think you should believe me, but if you don’t, that’s no problem, because I have evidence.

Suffering for the Children

Childbirth is painful. Men don’t know how painful it is directly, but women have produced some comparisons.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists commissioned a survey in honor of Mother’s Day in 2018. In it, some 45% of moms compared childbirth to “extreme menstrual cramps”, 16% compared it to “bad back pain”, and 15% compared it to breaking a bone. According to urologist Mike Nguyen, a Scandinavian study from 1996 saw first-time mothers rating childbirth between a 7 and an 8 out of 10, whereas mothers with multiple births rated it 6 to 7. 287 kidney stone patients rated their pain with stones at 7.9 out of 10, which was “very similar to that of childbirth”.

In another study, women and men who had suffered through renal colic (kidney stones) reported that stones were extremely painful, with a greater than 9 out of 10 rating for both sexes. The samples were small (23 women, 36 men), but 78% of the women and 89% of the men said kidney stones were the worst pain they had ever experienced. They were also asked to compare the experience to childbirth among the women who had given childbirth, while the men just had to guess. 37% of men said kidney stones were worse than pregnancy, while 24% said it was about the same. However, among women, 63% said kidney stones were more painful and a further 16% said they were about the same. Women were more likely to say kidney stones were worse than childbirth!1

In the popular imagination, kidney stones are among the most painful experiences possible. They’re bad, and they’re apparently not that much worse than childbirth. That said, child birth is still in the same ballpark as kidney stones, so it must hurt a lot. It’s no surprise, then, that the majority of the women in the U.S. who give birth now use epidurals. In fact, many women use epidurals despite being hesitant towards them.

The most likely reason so many women use epidurals is probably that they work.

One study asked a few hundred women about the pain they felt before and after the use of various non-pharmacological and pharmacological pain relief methods and epidurals were the clear winner. Physical activity barely did anything (the typical woman recalled going from a rated pain level of 6 to 5); water immersion dropped ratings from 7 to 5; nitrous oxide brought people down from 8 to 6 and opioid analgesics dropped people from 7 to 5. Epidurals brought pain down from 8 to 3.2

But what if epidurals hurt the baby?

A 2004 study found that epidural usage was significantly associated with Asperger’s, and marginally nonsignificantly associated with autism in general. The study got little attention, but it also wasn’t debunked.

Then 2020 rolled around and the idea that epidurals might lead to autism started to gain momentum.

The idea was resurrected in a 2020 JAMA Pediatrics paper by Qiu et al. In a dataset with some 147,895 children, they observed a sizable signal: controlling for numerous covariates, there was a robust association between epidural usage during labor and the risk that a child would be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The effect was fairly large for such a one-off, with risk being elevated by 37% for the mothers who opted for an epidural. But that wasn’t all! Qiu et al. also found that the association held up excluding premature births or children with birth defects, and there was a dose-response relationship: mothers who used epidurals for longer had a greater risk of having a child diagnosed with autism!

Partly because of how much epidurals matter for pain relief, this study set off alarm bells. There was a lot of worry that this could result in a fiasco a la “vaccines cause autism”. After all, even if the study doesn’t hold up, the public might only ever learn about Qiu et al.’s results rather than their debunking.

But debunking wouldn’t be easy since the results were supported by animal models. The support offered by these animal models was tenuous, but it still existed, so it made the whole thing more plausible. The study in question compared 11 Rhesus macaques whose mothers were given an epidural drug to 8 control macaques and they found that the ones exposed to epidurals acted strangely and developed motor disturbances, among other potential issues. Since this was an experiment, it’s much harder to question than the cross-sectional evidence brought forward for humans.

Come 2021, Wall-Wieler et al. had written up and published a contradictory study in the same publication. They had data from 123,175 newborns from Manitoba and with that data, they were able to observe a replication: the use of epidurals was related to 25% higher risk of autism in an uncontrolled model. Adding in more and more controls, the association shrank, until it reached a marginally nonsignificant 8% greater risk, all else accounted for. But the authors also had results from a subset of the population including 80,459 siblings. With all of their controls in place, the odds ratio dropped to 0.97 and was certainly nonsignificant.

This study wasn’t a final resolution. It didn’t have the statistical power that it needed to be one, and their result relied on using a lot of adjustments that other researchers might find questionable. These researchers evidently didn’t know that too many adjustments might make a result less plausible. If they had found there wasn’t an unadjusted association within sibling pairs, that would have been one thing, but they didn’t show that result so the possibility epidurals cause autism remained on the table.

Later that year, a JAMA publication by Hanley et al. came out, and it was accompanied by a publication in the same journal by Mikkelsen et al. Hanley et al. found a small association between epidural use and autism risk in a sample of 388,254 kids births in British Columbia. With controls and, again, using discordant siblings, the association was still there, but it was no longer significant. This wasn’t enough, however, as the estimates across specifications were very similar, the standard errors had just become large in the sibling analysis. Mikkelsen et al. found a nonsignificant 5% increase in risk with a sample of 479,178 Danish births. But, before adjustment, the effect seemed to be a 29% increase in risk. Mikkelsen et al. could reject their unadjusted estimates were the same as their adjusted ones, but that, again, might be down to questionable methods, so these two papers weren’t decisive either.

Even later that year, the British Journal of Anaesthesia published a study by Ren et al., where they were able to examine the association in a sample of 624,952 Danish births including 80,862 siblings. Ren et al. found an 11% greater risk of autism in the full cohort, but only a nonsignificant 3% higher risk between siblings. As in earlier studies, these risks weren’t distinguishable, so the debate could rage on.

The next year, JAMA published another piece, this time by Murphy et al. Using a sample of 650,373 births from Ontario, they found an unadjusted 30% increase in the risk of autism for mothers who used epidurals and an adjusted 14% increased risk. All of their results were directionally consistent and at least nominally significant, so this paper added to the case that epidurals cause autism.

The question was puzzling: by then several studies had been conducted and they all had fairly large samples, but there was still no especially strong evidence against the idea that epidural usage and autism rates were related. On their face, the results may have even been strong enough to motivate doctors to recommend women forego epidurals.

It’s lucky that we now we know the answer.

In late 2022, Hegvik et al. published a study two years in the making in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Their sample was large enough to resolve the question, and their team was more than qualified to know what methods had to be used to deliver a satisfactory and reasonably final answer. They had data from 4,498,462 births in Finland, Norway, and Sweden, and they knew not to do any questionable adjustments, preferring instead to stick to the basic and acceptable ones including sex, birth year, birth order, and controlling for unobserved familial confounders through the use of sibling comparisons.

The paper included documentation of the increase in epidural use, which could be argued to have contributed to increased autism and ADHD rates:

The paper established the plausibility of the link between epidural use and other outcomes that had trended up in the same time period, and then it tested them:

They weren’t there: siblings who were exposed were no more or less likely to develop ADHD or autism than their sibling who wasn’t exposed to an epidural.

There’s a lesson in here about the need for data to be open so that large analyses are possible and so the people with access to data can be the ones who know what methods to use, but there’s also a lesson about plausibility.

The original paper from 2004 found what it did, but it was small, and it showed that epidural usage was selective:

[Cases] had significantly older parents and were more likely to be firstborn. Case mothers had greater frequencies of threatened abortion, epidural caudal anesthesia use, labor induction, and a labor duration of less than 1 hour. Cases were more likely to have experienced fetal distress, been delivered by an elective or emergency cesarean section, and had an Apgar score of less than 6 at 1 minute. Cases with a diagnosis of autism had more complications than those with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified or Asperger syndrome. Nonaffected siblings of cases were more similar to cases than control subjects in their profile of complications.

Other studies have shown that epidural acceptance is related to things like “education, income, and parity”, and several of the studies that came along before Hegvik et al.’s had noticed selectiveness too.

But, you may say, there was experimental evidence from monkeys!

Alas, that evidence wasn’t very good. The monkey epidural drug study was small, and the dosage used in the study was atypical for human births, despite the study suggesting otherwise.

All the evidence was selective or poor, but access and analytic limitations meant it still took years to quash this potentially worrisome finding.

Sharing Is… Divisive?

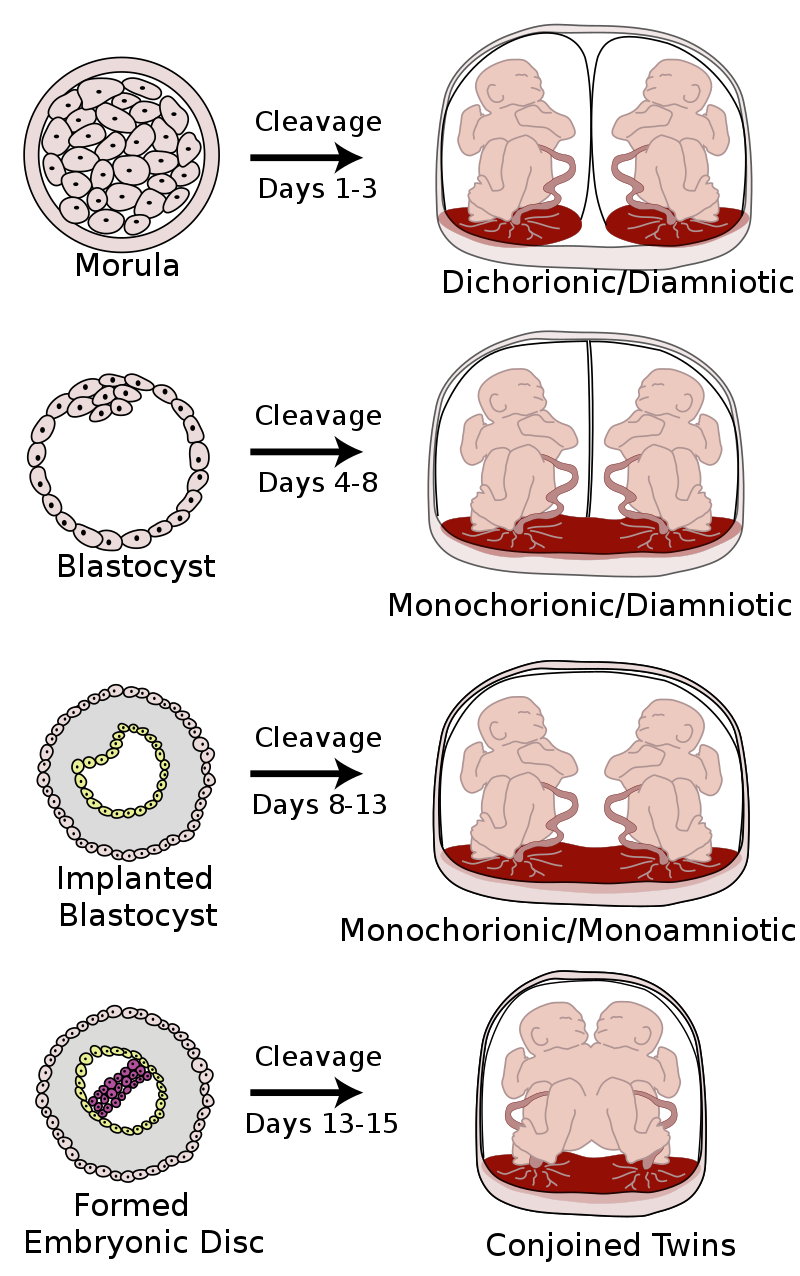

Twins share a greater or a lesser proportion of their prenatal environments depending on when the fertilized egg divides:

It’s reasonable to expect that if the prenatal environment is more shared, twins should be more similar. Luckily for us, plenty of people have had this idea, so this has been investigated!

A 2015 study used data from the Netherlands Twin Register and showed the trait correlations for monochorionic and dichorionic sets of identical twins. The difference between the two sets of correlations across all the observed traits averaged out to 0.003.

The notable exceptions to the finding of practically no effect were when monochorionic twins were found to be more similar for blood supply-related traits. The study’s authors concluded that “the influence on the MZ twin correlation of the intra-uterine prenatal environment, as measured by sharing a chorion type, is small and limited to a few phenotypes.”

A 2016 meta-analysis supported their conclusion. It found that “the evidence for bias due to chorionicity was mixed or null for many outcomes”, but “heritability estimates are underestimated for measures of birth weight and early growth when chorionicity is not taken into account.” All reasonable enough, and even consistent with Price’s review of primary biases in twin studies all the way back in 1950!3

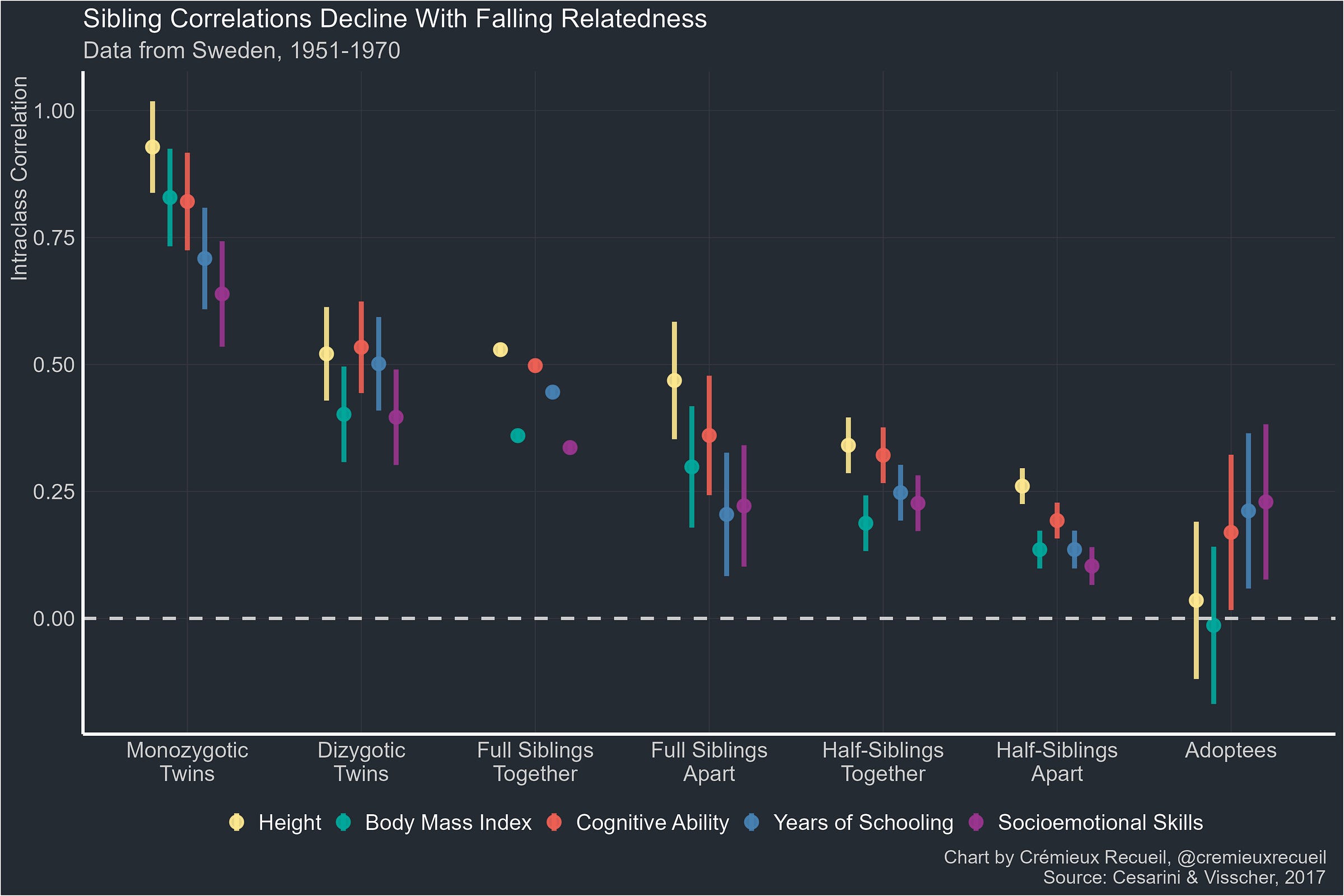

Large-scale Swedish register data also shows us that full sibling pairs and dizygotic twin pairs are equally correlated with one another in adulthood despite the dizygotic twins sharing the womb.

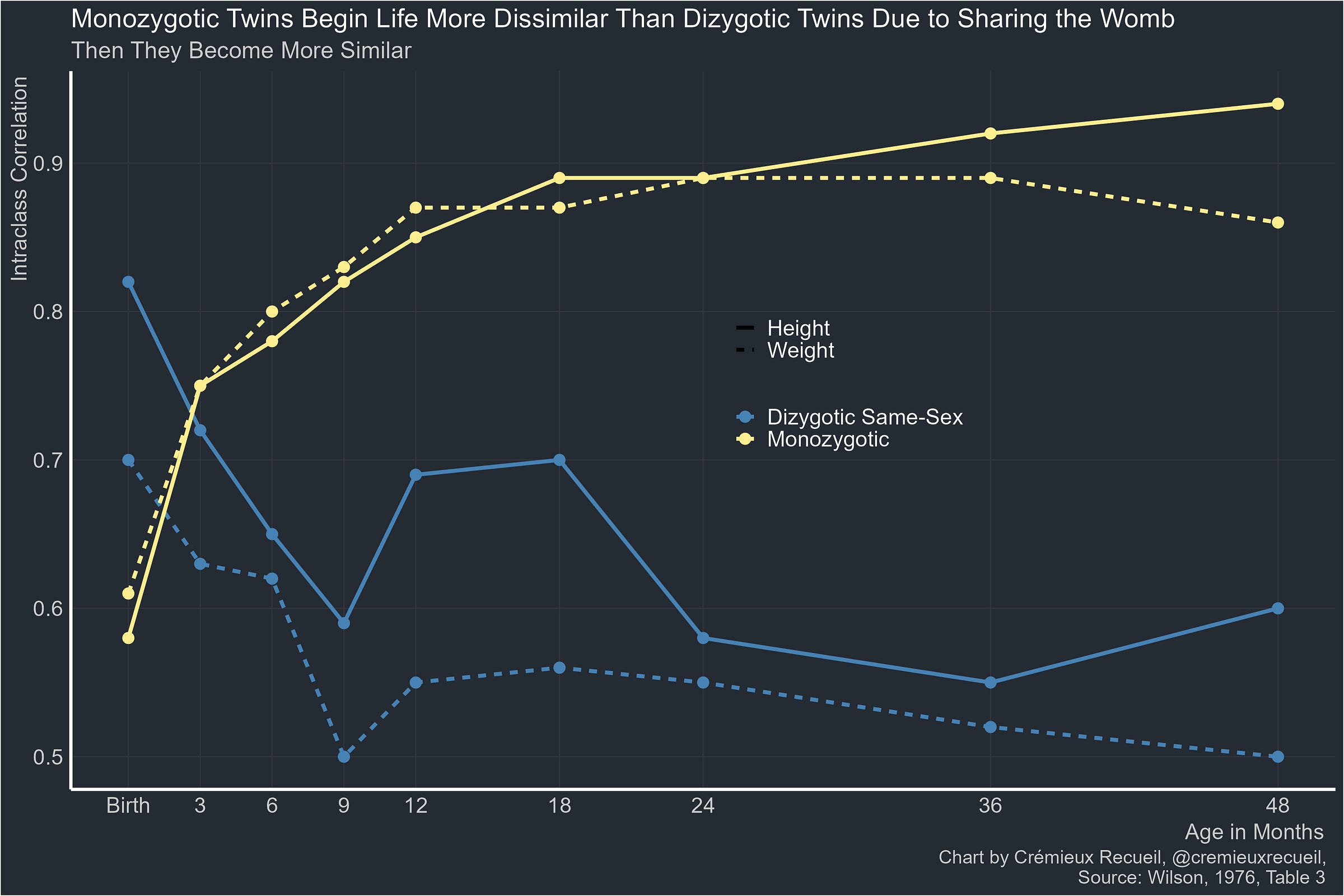

All of this is to say, the womb might not do what we intuitively think it does. In fact, it might do the exact opposite. Martin, Boomsma & Machin provided what I still consider to be the best illustration of what really happens back in 1997:

The reality is that twins become less similar thanks to sharing the prenatal environment. Because identical twins usually share more than fraternal twins, they’re born, in many ways, less similar to one another than fraternal twins are. And yet, over time, they become stereotypically similar.

The man usually credited with discovering this was one Ronald Wilson. In a 1976 study, he showed how this looks:

The Wilson Effect—the age-related increase in the heritability of intelligence—is named for him because of this and another discovery, made later in 1983: with age, fraternal twins become less similar to one another, approaching the similarity level of normal full siblings, while identical twins’ resemblance rises to almost the level of the same person taking a test twice.4

My point in presenting this information is that no one predicts it. If you told me you believed sharing the prenatal environment caused children to less similar to each other and you didn’t say that on the basis of empirical evidence like what I’ve shown here, I just wouldn’t believe you held that belief. It is incredibly intuitive that sharing the prenatal environment would make people more rather than less similar, and given how important early development is believed to be, it makes very little sense that its effects generally seem to wash out, but that’s what the comparison of fraternal twins and full siblings shows us happens.

This definitely can’t be your intuition if you believe older brothers spoil the womb and make their younger brothers gay. That’s the Fraternal Birth Order Effect hypothesis. The current meta-analytic evidence for it is consistent with no effect, while the current best evidence from a single study (which was larger than the combined sample from the meta-analysis) is that the effect is present but small. The most popular proposed explanation for the effect is that mothers’ immune systems become more sensitive to male fetuses if they have multiple sons. One explanation is that they develop more antibodies for the male protein NLGN4Y, causing problems for later-born sons’ development because the maternal immune system attacks the growing baby, somehow making them more likely to be homosexuals.

This explanation looked plausible enough based on the finding that antibodies to this protein were more common in the mothers of gay sons and potentially in mothers with more sons in general. But it turned out that intuitive theory-building wasn’t workable in this case, and the largest study out there now supports a slightly reduced effect for women, too. Because the various studies that came before the current best one didn’t have the power, they couldn’t detect the effect that’s now clearly-evidenced in women. Because early work lacked the power, researchers may have wasted time looking for male-specific explanations for an effect that doesn’t discriminate.

We can’t necessarily follow our intuition—whether it’s for initial studies, or for later studies of a phenomenon—or we might end up with little more than navel gazing. And to think! With more open data, years of hypothesizing and researching could have been obviated.

Misinterpreted Immunological Assumptions

The Maternal Immune Activation (MIA) hypothesis suggests that when a pregnant woman's immune system is activated, for instance, due to an infection, stress, or other environmental factors, this activation impacts the development of the fetal brain. This effect is particularly significant because the fetal brain is believed to be in a critical stage of development in which it is particularly sensitive to external influences.

The proposed impacts on the brain can include alterations in the growth and connectivity of neurons, changes in the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, and disruptions in the formation of synaptic networks. Some researchers believe MIA has especial relevance for neuropsychiatric disorders, such as autism and schizophrenia.

In Google Scholar, searching for [“maternal immune activation”] produces 11,000 hits since 2010. The amount of money and time spent studying MIA is substantial. It only takes a quick search to find numerous instances where grants—which are sometimes very large for such a niche topic—have been handed out. The dominant research modality used in these studies has been described by Brown & Meyer:

With a few exceptions, epidemiologic studies of maternal immune activation generally aim to establish associations between infectious, inflammatory, or other immune exposures and risk of certain neuropsychiatric disorders, the latter of which are defined by the current nosologic system. On the other hand, most animal models of maternal immune activation are single-factor models, in which the isolated effects of maternal immune activation-related exposures are investigated with respect to behavioral, cognitive, neuroimaging, and neurophysiologic phenotypes in the offspring.

The research using these methods has brought forward substantial and seemingly replicable evidence from animal models showing that MIA is correct and outlining multiple mechanisms that explain why maternal infections during pregnancy have major impacts on children. There’s even human evidence that prenatal maternal psychological distress impacts children’s future neurodevelopment and that maternal cytokine and chemokine levels are associated with the risk of autism coupled with intellectual disability.5

Intuitively, MIA makes a lot of sense. It feels right given common knowledge about how neural development happens and how critical fetal development is in particular. We also have evidence that speaks to it from animals and humans, and it’s obviously a lot of people’s research priority. Since pregnant women can choose to stay indoors, if MIA is true, mothers who get sick during pregnancy will likely have to accept some responsibility if their children turn out badly.

Though the hypothesis, if true, matters, and it’s been the subject of research for more than a decade, there are scant few large, causally informative analyses of it that have been conducted in humans. That’s not all that surprising given how hard it is to access registry data, biobanks, or many other big datasets. So we’re lucky that on January 11, 2024, a large-scale analysis of 410,461 children from 297,426 British mothers was published.6 The article’s first author is appropriately named.

Hope et al. sought to test the causal association between maternal infection and ADHD, ASD, cerebral palsy (CP), epilepsy (EP), intellectual disability (ID), and any neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD).

Their first test used a negative control, where they looked at the effect of infection during pregnancy, infection a year prior to pregnancy, and infection two years prior to pregnancy. They did the same thing for episodes of mental illness. The effects of both variables at each timepoint were consistent, despite MIA suggesting it should be effects during pregnancy that matter:

The second test involved checking for a critical window during pregnancy in which the effects of common maternal mental illness (CM) and infection seemed to matter most.

Since the first trimester is when neuronal development, multiplication, and migration kick off, and the second tends to be when they branch and form synapses, those should be especially critical if MIA is going to have an effect. Perhaps, however, the apoptosis, myelination, and mass reorganization that occur in the third trimester mean it should be especially critical. This is unlikely, however, as most babies born at 28 to 30 weeks survive without complications, and that many weeks is about when myelination and the third trimester neural growth spurt usually start.7 Regardless of the possibilities, in this very large dataset, there doesn’t seem to be a critical trimester:

So far, these results seem consistent with selection into both mothers who would confer greater neurodevelopmental risk being mothers at a disproportionate risk of becoming infected, during and prior to pregnancy. But selection as an explanation for this association could have been supported much more strongly by assessing the effects of paternal mental illness and by looking at post-pregnancy infections. Hope et al. didn’t check those things, but an earlier study of 1,206,600 Danish children did.

In that study, there were significant effects of maternal and paternal infections, and the estimated effects of either parent having hospital contact on children’s mental illness risk weren’t distinguishable.8 Post-pregnancy effects were also observed, further strengthening the argument that selection might play a role in the association between infection and child mental illness.

There was evidence of selection in Hope et al.’s study and in the prior literature, but Hope et al. also wanted to estimate the causal effect of an infection during pregnancy.

Their final analysis involved checking the effects of maternal mental illness and infection during pregnancy between siblings and the result was clear: a fully-attenuated effect, before and after adjusting for a litany of control variables.

This evidence is strong enough to eliminate many of the proposed mechanisms that explain MIA. In fact, it’s strong enough to say that, as it’s typically specified, MIA just doesn’t seem to be true for humans. If animal models of MIA are capturing something real—and they very well might be!—then they’re either modeling the wrong mechanism or there’s a problem translating that mechanism to humans.

Why Not Something Else?

MIA is heavily and expensively researched, intuitively plausible, and it sounds fancy and technical because it’s at the intersection of neuroscience, animal studies, immunology, neurodevelopment, and women’s health. But clearly much of the research on MIA has been a waste. In this article, I believe I’ve shown what I believe to be the problems that led to so much waste on MIA.

Small, intuitively compelling studies seed the growth of many lines of misdirected and potentially pointless research, including so much of the research on MIA. Small studies are inherently problematic because of their imprecision, their susceptibility to the Winner’s Curse, and so on.

But small studies can inspire explanations, and in the case of MIA, they did, leading to multiple apparently-supported mechanistic proposals. But this sort of work is misguided when it provides explanations for things that are not real. This happens all the time, so it’s not uncommon to see examples where there are “well-supported mechanisms” underlying phenomena that don’t exist.

At some point in the process of research, intuition can take over. Earlier findings said this or that and they had such and such evidence. The evidence mounts, the pile of papers grows to a staggering height, and the evidence in favor of a hypothesis becomes so great that it fundamentally cannot be questioned. The only thing left to do is to explain the findings, and to provide explanations that comport with the assumptions and methods of the research programme.9

To borrow from Lakatos, the intuitive appeal of the basis and between the parts of a research programme allows it to become degenerate, to only make meta-progress that ends up ultimately telling us nothing about the real world.

I think the tendency to end up like this is only natural. After all, we are intuitive animals: when something jives, we believe it and when something doesn’t we don’t. For academics, things frequently jive together that are completely constructed and which all might be false: “X et al. found Z to be true, which suggests hypothesis Q will be true but not W. We should pursue Q, since it follows naturally and logically from Z”, where Z may not be be false. If a study manages to affirm Q, which may also be false but could be verified through some consequence of Z alone, they may move on to Y, and so on and so forth, with every step and every inference potentially being another one that’s underwritten by shoddy work that might be irrelevant to the initial observations inspiring it.

There’s no way around this problem for some hypotheses, but for many others, there is.

The answers for questions like “do epidurals cause autism?”, “does the womb make siblings more or less similar?”, and “do maternal infections during pregnancy cause children to become mentally ill?” should have their first answer come in the form of a massive design-based test. All of these questions can be answered with data that’s already collected or that will soon be collected. But most of the required data isn’t accessible, and this is only a feasible suggestion if data is available. No one would have had to wonder about any of these questions for any amount of time if registers were open, if biobanks were free, and if researchers shared the data they often dishonestly say they’ll make available upon request.10

Making data radically more open could prevent small study effects and limit the mistakes we make and the mistakes other people make based on the mistakes we made (and the mistakes we make based on the ones they made!). Radical openness won’t eliminate the rot in science, but it is an inevitable component of getting there.

Not significant.

The differences in starting and endpoints may indicate selection in various ways. For example, the women who opt for non-pharmacological means of pain relief might be selected for thinking less of pain, or the women who are experiencing the most pain might opt for pharmacological pain relievers.

The studies in the meta-analysis also lets us check the specific claim—sometimes made—that sharing the chorion is relevant for kids’ IQs. In a √N-weighted, inverse variance meta-analysis of the studies between 1978 and 2016 with the Sidik-Jonkman estimator for τ² and Fisher’s z transformation for the correlations, the fixed effects meta-analytic outcome is a correlation of 0.0196 (-0.0908-0.1295), and the random effects correlation is 0.0200 (-0.0920-0.1316). These correspond to Z-values of 0.35 (p = 0.73).

In other words, the test-retest reliability.

The former study is a small fMRI study without a design that could account for unmeasured confounding. The fMRI literature suffers from low power because fMRI results are unreliable and samples are small and it is plagued by publication bias. It is not good evidence.

The latter study is a retrospective case-control study and is thus highly susceptible to recall bias. Like the former study, it didn’t have a means to address unmeasured confounding.

An earlier, similarly large study from 2022 by Brynge et al. used data from Sweden and had similar designs, but had a substantially lower reported infection rate, limiting their power compared to Hope et al.’s study. Nevertheless, they found that there was considerable evidence of confounding in the relationship between infection during pregnancy and the risk of child autism and intellectual disability, with ambiguous but nonsignificant results for the latter.

In 2018 Ginsberg et al. also found total attenuation of the association between infection during pregnancy and ADHD in a sample of just over a million Swedes. They adjusted for covariates, then used a cousin control, and finally a sibling control, and the effect was reduced from an unadjusted hazard ratio of 2.31 all the way down to 1.03.

These things can take place after an early birth, though some room for this being selective and these things starting earlier in the babies born that early, facilitating them merely continuing after birth remains. A large amount of data would be needed to figure out the possibility of selectiveness and whether this is really a viable alternative explanation and, if so, to what degree.

But the paternal effect estimate was consistently smaller and often nonsignificant on its own after adjustments. This could speak to bad controls, fathers being less likely to be recorded than mothers (e.g., in single motherhood), and the consistently observed phenomena of men being more hesitant to engage with the medical system, resulting in fewer recorded infections out of the total number of times they were actually ill and, substantively, attenuated estimates. These possibilities are made more plausible in the Danish data through the observation of very different maternal and paternal sample sizes.

This is especially common when there’s a “mechanism” to explain things, because mechanisms—real or otherwise—are attractive.

This matters because, just as with “vaccines cause autism” and potentially with “epidurals cause autism”, false discoveries often have consequences.

Thank you for dispassionately looking at all available studies, reporting sample sizes, and discussing confounding variables. Few people do this.

It's nice to have things we don't need to worry about, but are there studies that point to things mothers or aspiring mothers *can* do? It's all very well if genetics is 90% of the game, but we still have to make choices about the other 10%.