What Happens When You Use a Biased Test for Admissions?

China's National College Entrance Exams provide an answer

This is the first in a series of posts with timed writing. If it takes me more than an hour to complete them, my text editor closes and what I’ve written so far gets deleted. I have not attempted this yet, and I am not attempting this blind; at the outset of writing this piece, I had an outline in my head of what I wanted to write and I have read all of the papers I mentioned in this at an earlier date.

Yale, Dartmouth, and MIT have brought standardized tests back into the admissions process. For bright-but-poor students, this is a godsend. The plain fact is that everything besides testing is useless or seriously biased, from interviews, to extracurriculars, to letters of recommendation, and practically everything else.

Some consequences of this fact were fact were recently documented in Chetty, Deming and Friedman’s paper on admissions to Ivy-Plus colleges (the Ivy League, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and Chicago).

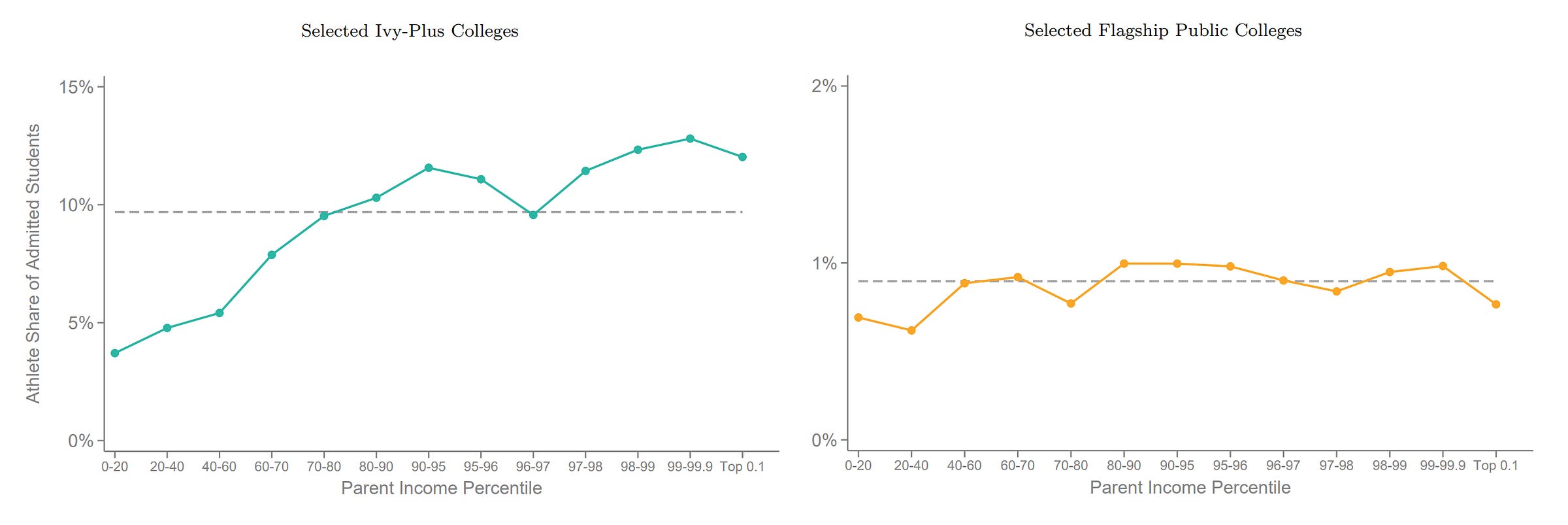

At the same levels of standardized test performance, the odds of attending an Ivy-Plus university were much higher for the students with the wealthiest backgrounds:

This reflects several things.

Firstly, the middle class know not to apply. They’re aware that selective universities discriminate, so they know to avoid the effort. They’re also aware of the costs if they’re not quite poor enough.1 This shows up in application rates (controlled for test scores):

The second factor the first graph reflects is that the odds of being admitted are vastly higher for kids from the richest families and lower for kids from the middle class:

The reason behind the advantage for rich students at Ivy-Plus institutions isn’t simply parents buying their kids admission, it’s through parents facilitating gaming the process. Rich kids are encouraged and able to obtain athletic admissions:

Rich kids benefit from legacy preferences:

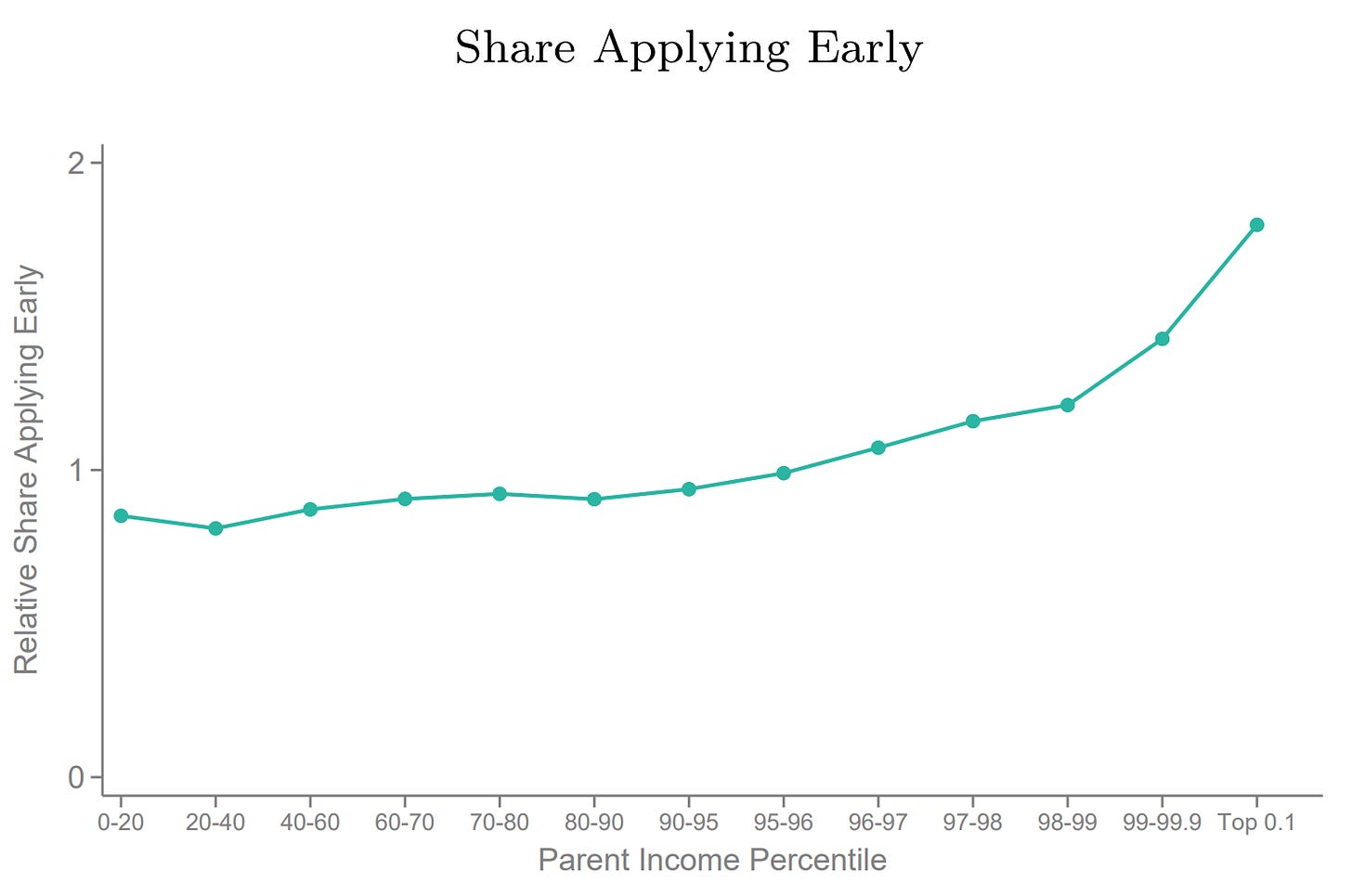

Rich kids can be more confident in their admissions and they’re aware of the advantages of applying early, so they do:

The advantage associated with income is minimal for similarly intelligent students. Wealth-related advantage accrues to the more subjective, non-academic components of applications:

That chart has a key concession: richer kids do perform better on tests. Plenty of people have argued that indicates they unfairly received more and better test preparation or better educations, but that’s hardly the case. We have plenty of datasets with class and intelligence test data. Tests like the SAT and ACT generally produce smaller class-related gaps than the gaps in latent g estimated from intelligence tests.

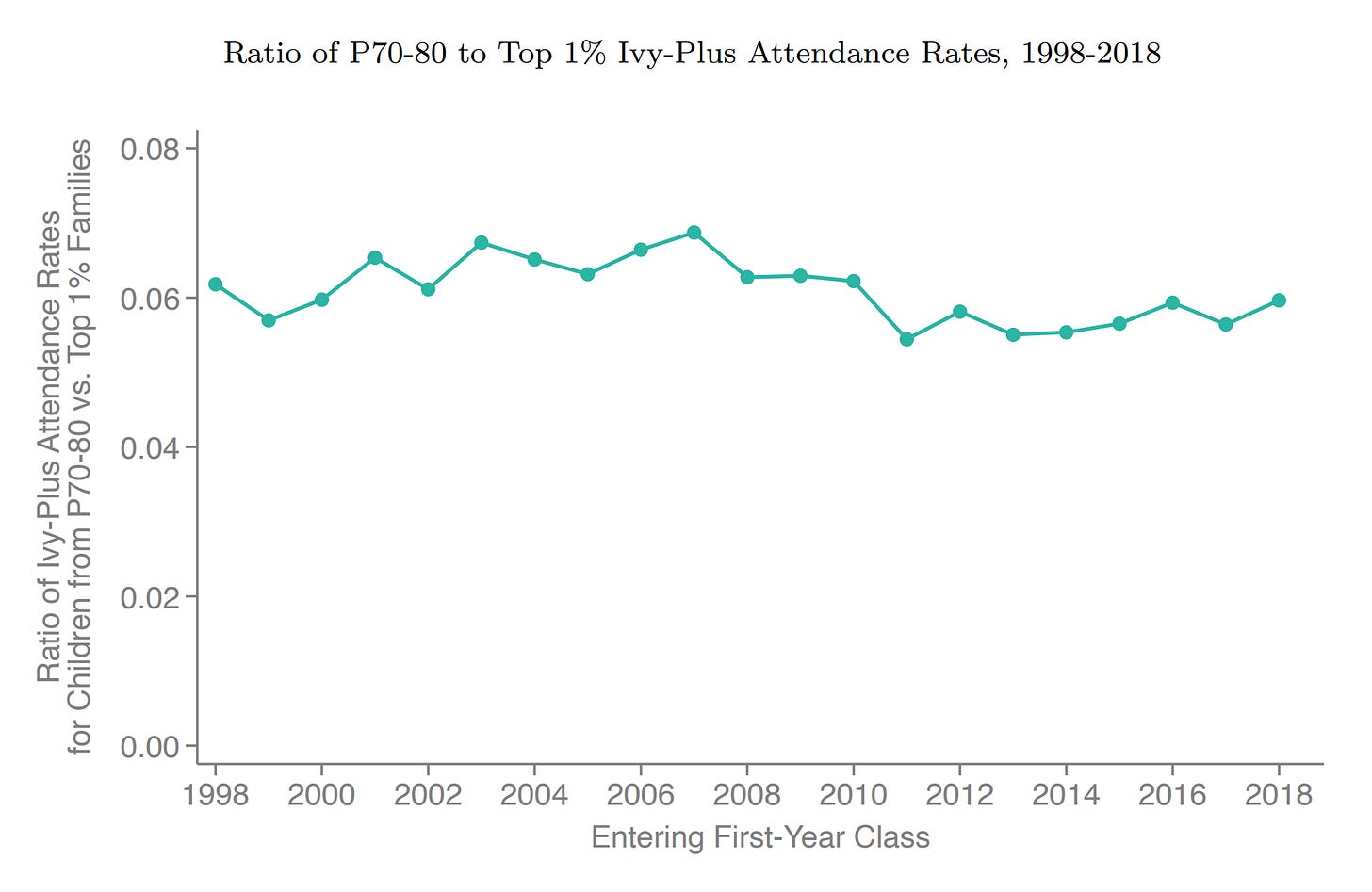

If anything, our expectation should be that education and the opportunity for preparation help those from the lower classes to catch up on the tests used in admissions.2 Consider recent years’ gaps in Ivy-Plus attendance rates for kids from the 70-80ᵗʰ percentile versus those from the 99ᵗʰ percentile. Without controlling for test scores:

The gap in Ivy-Plus attendance rates is massive before controlling for test scores. If test scores were equally able to be rigged as other aspects of the admissions process, we would expect to see equalization of test scores have little effect.3 That is not the case:

After controlling for test scores, the residual attendance rate gap in favor of the rich was ascribed to legacy preferences (30%), application rates (22%), nonacademic measures (20%), athletics (16%), and higher matriculation rates (12%).

It has to be conceded that, at the very least, test scores appear to be among the least class-biased parts of the admissions experience. Or as Chetty, Deming and Friedman put it:

Highly selective public colleges that use more standardized processes to evaluate applications exhibit smaller disparities in admissions rates by parental income than private colleges that use more holistic evaluations. While holistic evaluations permit broader evaluations of diverse candidates in principle, in practice they appear to create incentives and scope for students from high-income families to further differentiate themselves from others.

How Do Different Criteria Become Biased?

At most high schools, students earn a grade that reflects things like diligence in completing homework and projects, performance on quizzes and exams, classwork, and behavior—generally desirable qualities for students to have. But GPAs are usually biased. Grade inflation presents a good way to understand how that can happen. Consider this graph of the shares of underrepresented students arranged by grade inflation percentiles:

The greater the level of grade inflation, the smaller a school’s share of Black, Hispanic, and poor kids. First, with respect to race, what does that do to GPAs?

By 2016, Asians and Whites had gained an average of 0.12 GPA points, Blacks had gained 0.11, and Hispanics had gained 0.03, meaning basically no ‘progress.’ This change might seem small, but it should mean substantially greater shares of the groups experiencing >0.10 points of inflation are all-A students. A 4.0 for the most recent cohort of Asian students would be less impressive than it was 15 years prior, but for Hispanics, it would mean the same thing. But the admissions office doesn’t have the knowledge to make things right for the students who—due largely to the schools they were in—weren’t on the receiving end of grade inflation.

Later on in Hurwitz and Lee’s book chapter on this subject, they documented something similar for grade inflation by level of parental education: for those with high school dropout parents, GPAs only went up by 0.09 points, but for those whose parents had graduate degrees, grades went up by 0.15 points.

One potential reason for this is that educated parents recognize the competitiveness of modern admissions, so they send their kids to schools that hand out higher grades or they broker with schools and teachers to make sure higher grades happen. If that’s the case, admissions offices making use of grades will unduly favor those who could afford to bargain to earn their children higher GPAs.

One of the ways admissions departments can counteract this sort of inflation is to leverage students’ class ranks. If a student has a 4.0 GPA and they also have a poor class rank, that indicates they’re applying from an easy school and their GPA should be downweighted accordingly. But the biggest grade inflation offender schools seem to know this and, accordingly, they disproportionately suppress rank information. Students entering the most competitive colleges have become the least likely to have a known class rank:

The schools the kids entering the most competitive colleges from are less often public, more often independent, religious, and they’re full of smarter students and fewer poor students and minorities. Parents sent their kids to those schools, those schools gave them an easy pass, and they eliminated the information required for the admissions department to norm those kids’ GPAs!

The demise of the class rank has meant that GPAs are doubly biased—through allowing unfettered grade inflation, and through making it more difficult to objectively understand them.

These grade inflation findings replicated with respect to school-level socioeconomic and demographic composition in the ACT’s latest (2023) report on the topic. But they did not replicate in full, as there were actually no differences in the pace of grade inflation by level of family income, and Black and Hispanic students saw faster grade inflation than White ones. The results for family income may be due to using compressed family income brackets. The bins were <$36,000, $36,000-$60,000, $60,000-$100,000, and >$100,000, so any of the disproportionate benefits to those attending the wealthiest schools likely didn’t show up at the individual family level because of noise.

The ACT is important to bring up because it presents an alternative to class ranks. Standardized tests are capable of letting admissions offices norm students’ GPAs. If two schools send students with comparable grades but the SAT scores for one of them are much lower than the other, all else equal, we should consider the GPAs of the smarter students to be more impressive. If both ranks and scores are removed from the equation4 and the variance in GPAs has been reduced to the point where they can’t be used to reliably distinguish students anymore, admissions offices will be forced to rely on more biased, ‘holistic’ criteria.

Simply put, if GPAs cannot be normed, they will end up biased.

Inadvertent Bias

Sometimes, the biasing of a measure is less nefarious than wealthy parents moving kids to easier schools or pushing administrators to make unfair changes. Sometimes there’s bias with respect to a group simply because of how that group performs. For example, as the high school graduation rate has increased, it has been necessary to reduce required grades needed to pass. The way this is done isn’t by actually changing an F to an E or anything like that, but instead it’s done by raising the grades, and disproportionately doing so for the lowest performers within schools. This is a major part of why there has been so much grade compression, especially lately.

A clearer way to see this at work is to look at high school exit exams.

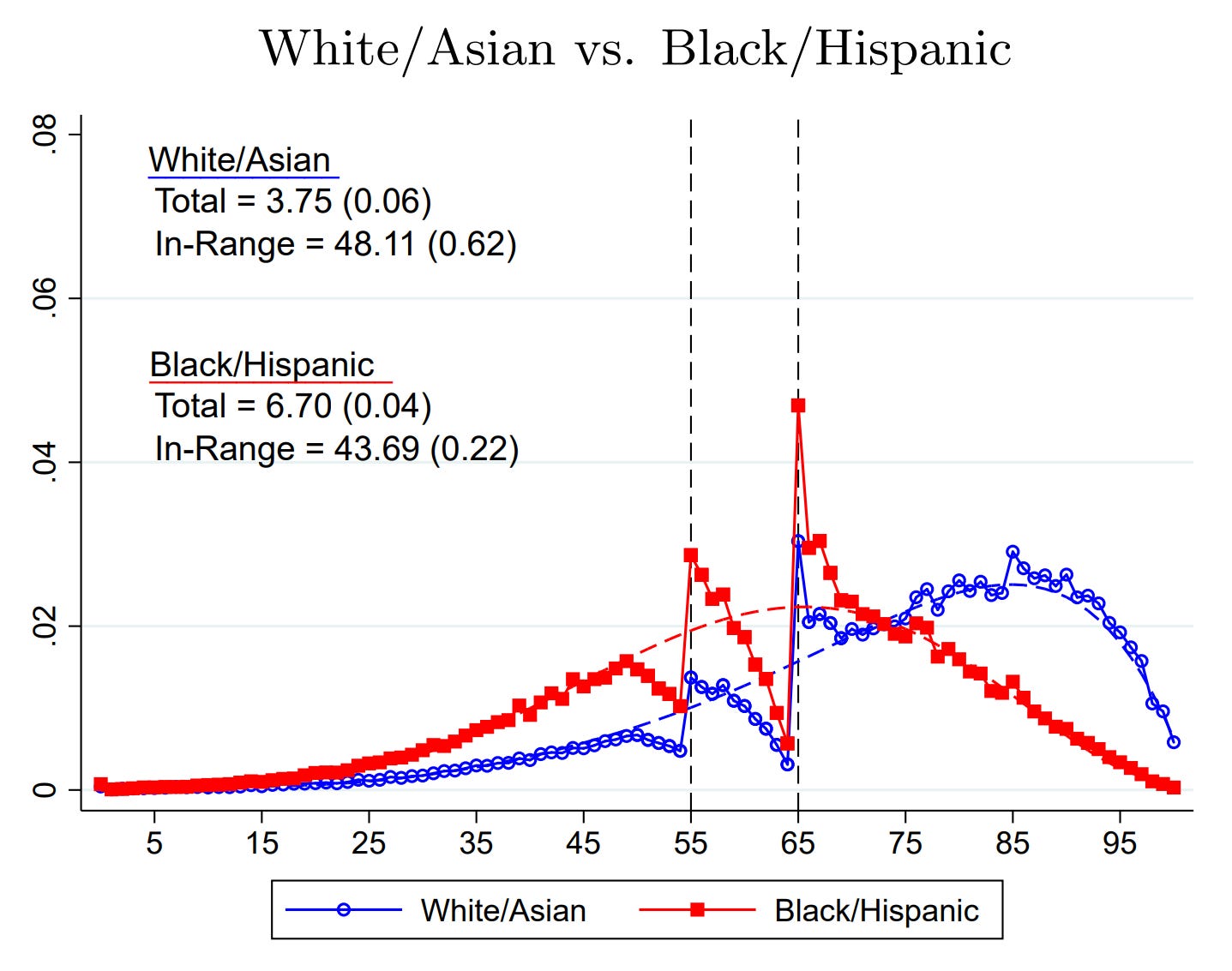

In New York, seniors take the Regents Examinations in order to graduate. When teachers became the graders instead of having a centralized state-level authority doing the grading, they very clearly cheated so more students would pass. To obtain a low-level “local diploma,” students had to score 55 on the exams; to obtain the prestigious “Regents Diploma,” they had to score 65. Scores in years where teachers weren’t doing the grading were nearly normally distributed; when the teachers took the wheel, there were an excess of scores at either cutoff:

When the scores are split by race, we see this:

This cheating behavior led to the tests being biased in favor of Blacks and Hispanics over Whites and Asians, but the reason doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with racial discrimination by teachers in favor of Blacks and Hispanics.5 Instead, it has to do with Blacks and Hispanics scoring worse, and potentially with the fact that they tend to go to schools with more low-scorers, which might offer further incentives for teachers to round up. As a result, their mean scores clearly became incomparable to those of Whites and Asians, but the bias was because so many more of them were in need of teachers’ help cheating the grading system so they could pass.

It Can Be Hard To Tell

Some of the class advantage in admissions is direct—for instance, legacy preferences directly favor the wealthy6—but a major component of them is indirect —for instance, via the aforementioned choice to send kids to schools where class ranks are suppressed, which might simply be done because of something like social pressure from friends who have also sent their kids to those places. Bias with respect to schools is hard to decipher though, because it could be both direct and indirect. For example, teacher and guidance counselor ratings are class-biased: rich kids go to schools that work to get kids great ones! But we don’t know how or why that happens.

Something is certainly happening—after all, high school origin seemingly matters more for the rich—but we don’t know if this is a direct or indirect effect, and it’s most likely a mixture of both.

Biases emerge in complex ways. In the past three sections, I’ve noted that it can be hard to figure out why something is biased; bias can emerge for various reasons, and; rankings and test scores can help to eliminate the bias in other instruments, because they are either locally (ranks)7 or generally (tests) unbiased. This is why standardized testing is a tool that helps to bring about real equality across levels of socioeconomic status, wealth, education, etc.

So what happens to admissions if we use a biased test?

The Gaokao

The Gaokao is China’s National College Entrance Exam (NCEE). Since 1952, it has helped studious kids to get ahead in spite of their backgrounds. There have been cheating scandals but, in general, the prestige accorded to the exam and the ability to majorly benefit from doing well on it are something to be lauded.

But prestige and importance come with downsides. The fact that the exam matters so much has meant that it is highly competitive; even small score improvements can make or break a student’s attempt, and the stresses that come with that fact can be immense.

Exam takers all take Chinese, mathematics, and English examinations that each account for 150 points. From there, they choose different tracks, like STEM and humanities, which have their own three special subject tests worth a total of 300 points. Grading is done at the province level, so scores can only be compared within the same track and province. Due to changes over the years, they can also only be compared within cohorts.

English was first introduced to the exam in 1978 and at the time it only included a basic reading comprehension and essay section. But 21 years later, the Ministry of Education deemed the subject of such great importance that the exam was set to incorporate a listening section in each province’s version of the test by no later than 2003. Students sitting the exam all gather up in a room and are played conversations in English over loudspeakers and then they’re asked questions about what was said.

The issue with adding listening to the English exam grade is that there are extremely large province-level differences in the opportunity to learn English well enough to comprehend a listening exam in it. From the top:

Teachers in rural areas are less proficient in English themselves, so the quality of English listening instruction is poorer for their students.

Rural teachers, being less qualified than urban ones, would have had more trouble adapting to the instruction required to facilitate students’ English listening skills.

Rural schools in China lack digital devices in ample enough quantity and of high enough quality so that students can receive English listening instruction that way.

Extracurricular English exposure is more limited for rural students as compared to urban ones. This includes through sources like

Foreigners

Parents educated in English

English movies and television

The cultural relevance of English learning material is often less for those in rural environs, since they have less reason or intent focus on international affairs and media.

The rewards to knowing English are less in the rural Chinese labor market.

It’s apparent: the introduction of an English listening test should disadvantage rural Chinese test-takers because, at the same levels of ability, they’re less able to obtain the educations required to do well on the exams.

A brilliant new preprint by Li et al. has documented what happened when this biased test was administered against everyone’s better judgment.

The first thing to note is that the bias in the process was apparent early on. Look at the dates and ways different provinces introduced the English listening requirement:

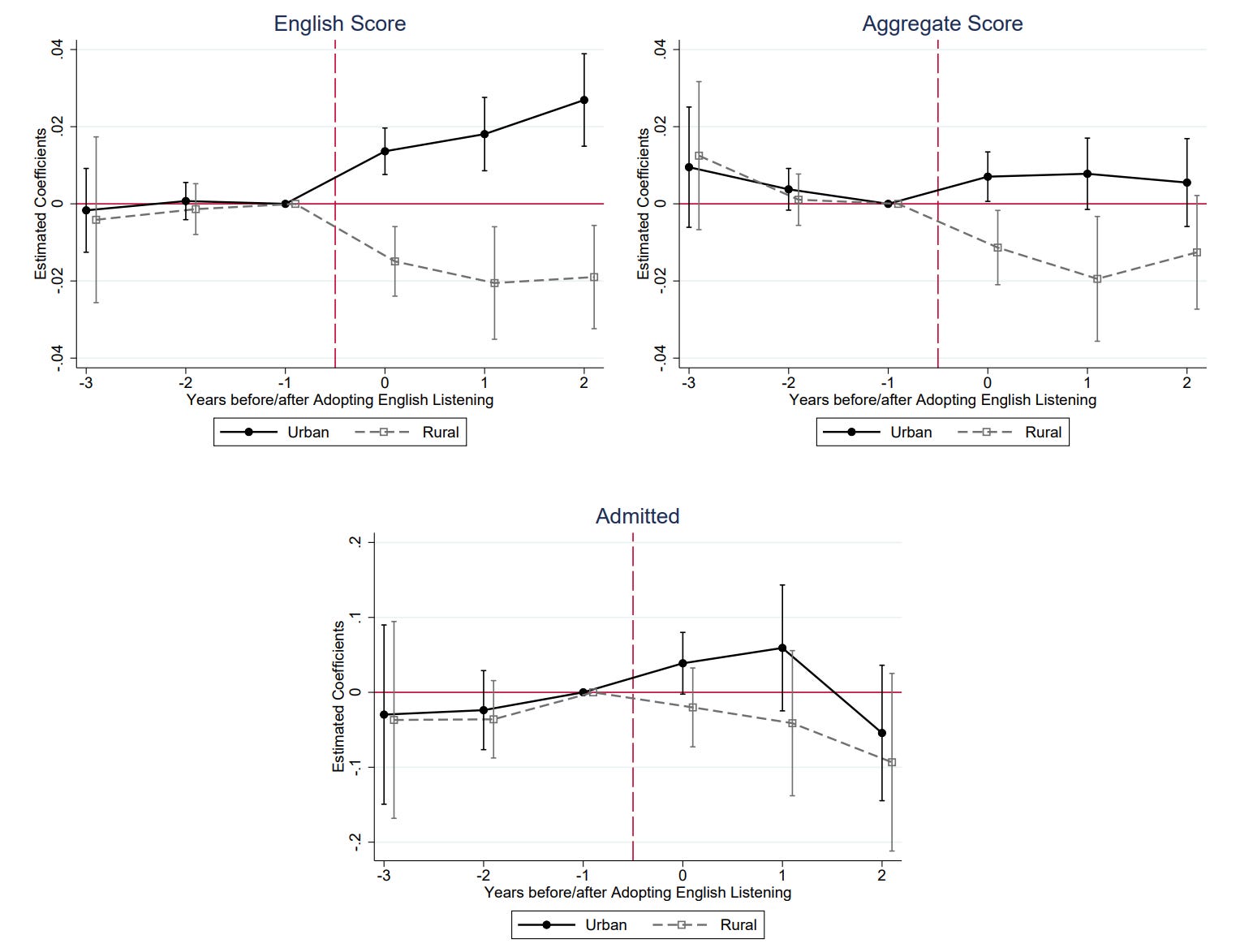

What happened in the pilots? Rural scores dropped. What happened when the exam was adopted anyway? Rural scores dropped, as predicted and as shown:

The predicted concentration of the anti-rural effect of the listening exam on the English language test is visible. The competitiveness of the Gaokao is visible too because, even though rural test takers only lost a small amount overall because the listening test was a modest part of their English grades, they were admitted to colleges considerably less.

The anti-provincial bias of these exams passes Berkson’s Inter-Ocular Trauma Test:

In 2005, only two short years after the exam was foisted on each province nationwide, the Ministry of Education issued a follow-up so that provinces could choose whether they were going to administer the listening exam or not. More than half of the provinces got rid of the test within the decade.

Should China Keep the English Listening Exam?

An unfortunate part of the English listening exam debacle is that it’s a justifiable test. Think about medical exams. When they’re found to have biased items, committees look at the questions and then they often make the decision to keep those items in the tests. The reason to keep biased items is that they ask about important topics. For example, women’s health is important to many doctors, but questions about it will almost always favor women. That’s almost unavoidable, but if the questions are out, men might never learn about the content. We end up with good reasons to keep the questions in, unless we want to segregate doctor-patient pairs on the basis of sex.

Adopting the English listening exam was criticized for its anti-rural bias; dropping the exam has been criticized for promoting “dumb English.”

If there really is little incentive for test-takers to improve their English language skills in a way that matters (i.e., by being able to understand and speak it), then the English language test section is trivialized in its importance. Many students won’t need English, but if the goal was to promote learning it because of its usefulness, dropping the most useful form of it because of bias could end up being as big a mistake as dropping women’s health questions from medical exams.8

The fact that tests are generally unbiased is an important one. The fact that some important9 tests are biased is also an important fact. Truthfully, there will always be some subgroup for whom a given test item, section, or subject is biased. So while tests can easily be put to use to take the bias out of admissions processes and hiring, that may not always be what we want.

At the same time, universities like Harvard and Yale engage in the practice of recruiting to reject. This leads to relatively many applications from the poorest families and from poorer groups in order to reduce the appearance of discrimination by giving those groups higher rejection rates, like the rates experienced by everyone else.

Rich students may retake tests more often. Two problems for this are

One could argue better educations mean higher test scores for the rich. Three problems for this are

Schools have limited ability to impact kids’ cognitive ability, the main driver of test scoring.

Gaps are established early on, prior to most education taking place. We can also see this at the level of latent g in the CNLSY, where the 90-10 and 75-25 gaps are stable across ages. In the same dataset, this stability across different ages is even visible at the observed score level.

This would lead to biased scores if the rich had educational resources that were not available to the poor.

One could argue the rich have access to more and better test preparation. The problems for this are

If, instead, the rich have access to better preparation, that would be biasing.

Since we do not observe bias, they must either not receive better preparation, or

That better preparation is not used differentially enough, or

The effect of said better preparation is too small to matter, given bias is not found in extremely large samples

Whatever way you slice it, the argument that the rich are privileged when it comes to test scores is weak. The argument that they are privileged when it comes to other aspects of admissions portfolio preparation on the other hand, is very strong.

Parental education is generally more predictive of kids’ intelligence than parental wealth, lottery and adoption studies show muted evidence of effects of wealth on cognitive ability, genetic correlations between socioeconomic status and intelligence are very high and environmental ones are low and often go in the wrong direction, Moving to Opportunity generated no apparent effects on kids’ test scores, impacts of changes in family structure are small, etc. We don’t need to belabor the point that the evidence for causal effects of wealth on ability is not great, the effects that are supported are, at best, small, and what we know of the effects suggest they are not general.

Since there is substantially more overlap between rich and poor in terms of ability than in terms of many admissions-relevant aspects of class privilege, this follows.

Ranks can be removed or trivialized by sending kids to smaller schools too.

Similarly, I once noted in an earlier piece that an item from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III was once found to be biased somewhat in favor of Blacks, but it turned out the bias was just a bias in favor of low performers, who were disproportionately Black.

In theory. In practice, ranks are usually just an improvement over GPAs alone and they remain biased for different reasons. For example, two students from the same school might take easier and harder classes and the one in the easier classes might end up with the higher GPA and thus the higher rank in that school. The utility of ranks is greater for fixing the variance reduction that has happened for GPAs than it is for establishing a high-quality rank order within a particular school. That’s why class details ought to be used as well, but those are also often suppressed. Some high schools attempt to obviate the issue with differences in difficulty by giving kids an extra 20% to their grade if they take AP courses or they’re enrolled in IB. This procedure might help, but it’s still not as good as simply using test scores. This is one reason why ranks are not a completely viable alternative to test scores.

This is not guaranteed by any means, hence the operative word being “could.” One can easily imagine a scenario where a person gets admitted on the basis of good written English language test performance and then moves to a university environment where they have more English exposure and that lets them learn the language well, where they might not have been able to before. The relative weight given to this sort of possibility versus the incentivization of English listening skills prior to test-taking needs to be considered carefully.

Because they assess meaningful abilities or incentivize studying to build meaningful skills.

The Ivy-Plus is well worth studying, but it has a separate problem: Maxing out on test scores and grades. When, hypothetically, all your applicants are 97th-99th percentile, the info is not as useful as 70th-80th percentile like for a worse school. So you need to use other things. I saw that problem in economics PhD applications from China, and it is a problem for PhD applications generally. A special test designed for people in the SAT 95th percentile plus (instead of the 50th percentile) is needed. Someone could make money creating and running it (an Ivy-plus consortium could do it).

So if I understand from a quick reading, bringing back some form of standardized testing for admission would help the students at the lower-middle end of the admissions spectrum, but “punish” those now at the higher end? That begs the question of whether the Ivy’s really want this. Much to be had from wealthy students and their families in this league—regardless of their current virtue signaling.