A Requiem for Nutrition

Food probably isn't making people smarter or dumber

The Economist has come out with a leader entitled How to raise the world’s IQ. This special report is a welcome one: it’s a fairly explicit acknowledgment that cognitive skills matter for global productivity, innovation, success, and all the other buzzwords about doing well that we’re familiar with. The reason this is so welcome is that it’s underappreciated and taboo that cognitive skills—national IQs, learning rates, national achievement, whatever euphemism you wish to use—matter for development. But not only are cognitive skills a cause of development, they are a major cause of development, and we have causal evidence for their importance. Consider these three different instrumental variable strategies:

Cranial capacity, a proxy for evolutionary history, and numeracy in the fairly distant past are all capable of predicting growth rates today; given the large differences in national IQs between countries, this has major implications for national prosperity and, at a glance, raising national IQs definitely seems to be a good metric to prioritize.

But The Economist’s special report isn’t without problems. From the first sentence, there are errors. The first paragraphs read:

People today are much cleverer than they were in previous generations. A study of 72 countries found that average IQs rose by 2.2 points a decade between 1948 and 2020. This stunning change is known as the “Flynn effect” after James Flynn, the scientist who first noticed it. Flynn was initially baffled by his discovery. It took millions of years for the brain to evolve. How could it improve so rapidly over just a few decades?

The answer is largely that people were becoming better nourished and mentally stimulated. Just as muscles need food and exercise to grow strong, so the brain needs the right nutrients and activity to develop. Kids today are much less likely to be malnourished than they were in past decades, and more likely to go to school. Yet there is no room for complacency.

I believe James Flynn is now rolling in his grave.

If you are any bit familiar with the relevant literature, you probably know about Flynn’s antipathy for nutrition as an explanation for his eponymous effect. Flynn’s seminal study on the topic is the inspiration for this post’s title. In that study, he noted the following:

The hypothesis that enhanced nutrition is mainly responsible for massive IQ gains over time borrows plausibility from the height gains of the 20th century. However, evidence shows that the two trends are largely independent.1

And

[To] my knowledge no one has actually shown that American or British or Western European children have a better diet today than they did in 1950, indeed, the critics of junk food argue that diets are worse…. The major argument for nutrition as a post-1950 factor rests not on dietary trends, but on the pattern of IQ gains. It is assumed that the more affluent had an adequate diet in 1950 and that dietary deficiencies were concentrated mainly in the bottom half of the population. This has been stated as a hypothesis about class: Over the last 60 years, the nutritional gap between the upper and lower classes has diminished; therefore, the IQ gap between the classes should have diminished as well; therefore gains should be larger in the bottom than in the top half of the IQ curve.

With this key hypothesis noted, Flynn went on to look at what the data showed for both Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices (CPM) and Standard Progressive Matrices (SPM). For the CPM, gains circa 1947-82 averaged 0.170 points per year, with the top half of the distribution gaining 0.247 points and the bottom half gaining 0.100 points per year. 1982-2007, the average gain was 0.386 points per year with a rate of 0.519 in the top half and 0.357 in the bottom. For the SPM 1938-79, the top half gained less and the bottom gained more (“Less” and “More” are actually the ‘numbers’ Flynn provided), and 1979-2008, the top gained 0.072 points per year versus the bottom half’s gains of 0.243 points per year. Adding to this, Flynn noted that trends in Piagetian and Wechsler tests also did not strictly fit with the nutritional hypothesis. Reconciling these findings, Flynn wrote:

The totality of the evidence supports a summary conclusion. Enhanced nutrition has made us taller people and poor nutrition has made us more obese. But our diet today probably does not make us very different people from our grandparents as far as cognitive competence is concerned. Our brains have altered since 1900, and they are better brains for solving the problems of our time. But they have altered like a muscle, that is, they have altered because we use them differently than our parents and grandparents did. The causes of this are many and the effects of nutrition, at least since privation has been banished, are too weak to stand out from the crowd.

The evidence since Flynn wrote that article has been inconsistent with the Flynn effect being a well-defined pattern of gains. I’ve summarized that evidence and provided a novel analysis here.

The fact that the Flynn effect is poorly defined has complicated the search for causes, but it hasn’t made Flynn’s point about nutrition any less true. After all, the Flynn effect is generally greatly reduced in extent, eliminated, or reversed when correcting for test bias, suggesting that the phenomenon’s most major cause is something like getting better at tests rather than getting smarter. If nutrition were the Flynn effect’s major driver, there wouldn’t be so many cohorts where the biggest gains are among adults rather than children either!

In Flynn’s nutrition article and in his book What Is Intelligence? he made an even more powerful remark about nutrition. Quoting from the book:

We have noted that 20-point Dutch gain on a Raven’s-type test registered by military samples tested in 1952, 1962, 1972, and 1982. Did the Dutch 18-year-olds of 1982 really have a better diet than the 18-year-olds of 1972? The former outscored the latter by fully 8 IQ points. It is interesting that the Dutch 18-year-olds of 1962 did have a known nutritional handicap. They were either in the womb or born during the great Dutch famine of 1944—when German troops monopolized food and brought sections of the population to near starvation. Yet, they do not show up even as a blip in the pattern of Dutch IQ gains. It is as if the famine had never occurred.

Terrible Times Make For Powerful Studies

The era Flynn mentioned is more popularly known as the “Hunger Winter”, and it was a horrible time for those who went through it. But nevertheless, as Flynn noted, there was no evidence whatsoever that it made a dent in Dutch IQs, nor in their rise. Thanks to the draft, we have representative samples that speak to the lack of effect. In the diagram below, a lower score is better. Can you see the Hunger Winter?

I’ve written about this period before, including how it has replicated in different cohorts. One of those cohorts overcame the issue of confounding by survival—the confounding whereby the less intelligent might have been among the large number who were miscarried or passed away in their youth during the famine. The strategy that made an effect less likely was a sibling control, and the effect sizes ruled out with it were fairly small effects, of below about a fifth of a normative standard deviation (i.e., 15 IQ points) in size (i.e., 3 IQ points). Similar results show up in data on Holocaust survivors.

For completeness, I went ahead and replicated this result for individuals exposed to China’s Great Famine. I did this using the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a large longitudinal dataset that provides a representative sample of the Chinese population. In 2010, 2014, and 2018, participants took mathematics and language tests, which I treated as separate indicators of ability, controlled for age, wave, and sex, in order to model out trends in general intelligence over time. The latent variable model I used was the following:

g =~ Math1 + Math2 + Math3 + Lang1 + Lang2 + Lang3

Math1 ~~ Math2 + Math3

Math2 ~~ Math3

Lang1 ~~ Lang2 + Lang3

Lang2 ~~ Lang3Inspired by other studies using the CFPS, I increased my statistical power to detect bias by splitting the sample into birth cohorts with sufficiently large sample sizes to leave me well-powered, while losing granularity for trend detection. For bias correction, I followed the strategy I used in my article on Mensans, which involves adding dMACS to manifest scores to ‘even out’ the effects of measurement noninvariance in the loadings and intercepts of the factor model. dMACS does not correct biases that accrue in the residual variances, and comparisons with the earliest birth cohorts (1935-1944) each showed bias in the residual variances, which means different causes were at work in producing those cohorts’ scores, compared with later ones. Bias-corrected FSIQs and factor scores from models with freed biased parameters produced practically identical results.

What I found was, I believe, curious, as it jived with my impression from large-scale examinations given the world over: Chinese scores trended up over time, entirely due to violations of measurement invariance.2

What I’ve noticed in cases where scores in the developing world seem to rise is that the rise is due to tests becoming less biased, rather than latent ability going up. At least, this is the case whenever I’m able to obtain the data. This is supported by other data, like the results of ‘culture-free’ tests given in earlier generations. But that’s neither here nor there: what is apparent from this data is that China has been about as smart as it is now for a long time and despite the impacts of the Great Famine and Cultural Revolution, whatever they were.

Now we have to ask the obvious question: Does poor nutrition bias test scores? Unless people are starving while they’re taking tests or learning the material required to take them, my guess is no. What I think is more likely is that older generations weren’t educated as well as current ones; education didn’t make the youth any more or less intelligent, but it did allow them to perform like they should on IQ tests.

More to Flynn’s point, I’ll ask the question he can’t now: Why do manifest scores appear to linearly increase if nutrition is behind China’s rise? There should be a trend-break in the cohorts containing those affected by famines if nutrition is a strong force for change! It might be the case that less intelligent children died selectively during the famine or parents provided compensatory education for affected children or something else along those lines, but this was a famine that even removed class-biased protection against famine-related death because of the time’s hatred for the upper classes. If we narrow down the birth cohorts, nothing changes. There is simply no evidence that the Great Famine had an effect, let alone a large one, and if nutrition mattered a lot, then there should have been something.

Where’s the Convergence?

Beyond tragedy, we have to wonder about the longer term. Surely if nutrition were a primary driver of the Flynn effect—let alone intelligence—we would see it through the lens of group differences.

Focusing in on the Black-White gap, I’ve written about how it’s roughly 1 d circa 2023.

Roughly 1 d has been the size of the Black-White gap for as long as its been recorded. That was even the size of the gap among soldiers all the way back in World War I. Not to put too fine a point on it, but I’ve also written about how long the Black-White gap has been documented—consistently, well into the 19th century!

Gaps in education, nutrition, socioeconomic status writ large, and exposure to discrimination have certainly declined in recent generations. Gaps in exposure to biological-environmental variables like lead have also fallen.3

So, where’s the gap closure? If, after more than a century, 1 d has remained 1 d after major, objective improvements representing world-historic ‘catching up’ along several dimensions, then that places extreme limitations on what environmental explanations for the gap can do, and what can be expected from environmental improvements of all sorts more generally.

As I’ve shown in the case of China we can probably apply the same logic more globally. As Sebastian Jensen recently showed, even manifest national IQs are highly stable over time despite recent history’s well-known international socioeconomic convergence. Consider scores out of Sub-Saharan Africa from right after 1940 to the present day:

And to confirm what I’ve written, look at the graph Sebastian provided for China—a graph showing an ‘upward trend’ driven by a single early study and no real improvements in an era of major economic progress!

Where, exactly, does nutrition fit into a world with limited, artefactual convergence?

Nutrition On Trial

There is evidence that in utero iodine supplementation helps to boost IQs, but the iodine supplementation literature has also revealed shockingly limited impacts on adults. There is some quasi-experimental evidence that postnatal supplementation matters, but when it’s coupled with experimental evidence against postnatal impacts, it raises the question of when and whether quasi-experiments are to be preferred to experiments.

Since the quasi-experimental evidence sometimes rests on hard-to-justify assumptions, I’ll ignore it right now in favor of reviewing some trials. I’ll start with a well-conducted, large, randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Nepal.

Dulal et al. (2018): 1,069 Nepalese children’s mothers were enrolled in a double-blinded RCT of multiple micronutrient supplementation versus iron and folic acid supplementation only. Pregnant women were given supplements that tasted and smelled identical and were to be taken daily from the twelfth week of gestation through the end of pregnancy. The multiple micronutrient supplement contained vitamins A, C, D5, E, B1, B2, B6, B12, niacin, folic acid, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and iodine, and it resulted in a 77 gram increase in children’s birth weights, with gains still observable at the 2.5 year follow-up, but lost by 8.5 years in. The follow-up of kids’ cognitive function occurred at twelve years of age, and involved 813 of the original 1,069 children, and delivered null results. Using the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT), the fullscale IQs were minimally differentiated (IQ = 76.4 in control and 77.6 in intervention, p = 0.18), and the memory (p = 0.14), reasoning (p = 0.22), symbolic quotient (p = 0.25), non-symbolic quotient (p = 0.17), and the interference (p = 0.18) and facilitation (p = 0.51 and the wrong sign) sections of a Stroop test looked to be similar. Overall, the magnitudes and significance of the differences were not meaningful.

In their first supplementary table, Dulal et al. provided a review of prenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation trial effects on children’s cognitive outcomes, conducted in areas with poor nutrition and thus high expected returns to nutritional supplementation. These studies targeted at-risk people at the most critical developmental juncture, so the effects should be very sizable.

McGrath (2006): A sample of 327 in Tanzania was split to receive vitamin A or the multiple micronutrient supplement plus vitamin A or a placebo, and there was no practically or statistically significant effect on Bayley Scales of Infant Development II scores at six, twelve, or eighteen months of age.

Tofall (2008): A sample of 2,853 Bangladeshis were given early food plus iron 30 or 60 or a multiple micronutrient supplement versus usual food plus iron 30 or 60 or a multiple micronutrient supplement. When assessed at seven months of age, there were no differences in performance on problem-solving tests, the Bayley Scales, or behavior ratings, but there might have been an interaction effect such that the children of undernourished (“usual”) mothers performed better on problem solving tasks than the children of mothers who received early food supplementation (p = 0.04). This was not meaningful in size, was marginal, and it would not stand up to a correction for multiple comparisons.

Li (2009): 1,305 in rural areas of Western China were given either daily iron and folic acid or a multiple micronutrient supplement versus folic acid alone, and at twelve months, the multiple micronutrient supplement group had marginally higher performance on the Bayley Scales compared to the iron and folic acid (p = 0.02) and folic acid only (p = 0.02 also!) groups.

Christian (2010): 676 in Nepal were given daily iron and folic acid versus iron and folic acid plus zinc versus a multiple micronutrient supplement versus just vitamin A, and they were assessed at seven to nine years of age. The iron and folic acid supplementation group scored better on two out of four tests, but only marginally (p = 0.01 for the UNIT and 0.02 for backward digit span), while the other groups weren’t differentiated.

Prado (2012): 487 Indonesians were given daily iron and folic acid versus multiple micronutrient supplementation and nothing was observed except an interaction such that visuospatial ability was boosted in the children of undernourished and anemic mothers (p’s = 0.004 and 0.03) at 42 months of age. Only the former effect would hold up to correction for multiple comparisons, as many tests were given.

Hanieh (2013): 1,258 Vietnamese were assigned to twice-weekly iron and folic acid supplementation or twice-weekly multiple micronutrient supplementation versus daily iron and folic acid supplementation. The twice-weekly group had significantly greater scores on the Bayley Scales at six months of age, but the effect was marginal (p = 0.03), and given the daily group didn’t see an improvement, this seems like an unlikely outcome.

Li (2015): 1,744 in rural areas of Western China were followed up at seven to ten years after their mothers were assigned to daily iron and folic acid or multiple micronutrient supplementation versus just folic acid. There were no practically or statistically significant effects on Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) IQs or any of the index scores like verbal comprehension, working memory. perceptual reasoning, or processing speed.

Prado (2017): 3,068 Indonesians were assigned to a daily regimen of either multiple micronutrient supplementation or iron and folic acid, and at nine to twelve years of age, the kids took a large battery of tests including an information test, speeded picture naming, block design, the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, the Serial Reaction Time Task, the Adapted Visual Search Task, forward and backward digit span, Stroop numbers, the Dimensional Change, the Card Sort Test, and they were provided an NIH Toolbox composite score. Multiple micronutrient supplementation was associated with marginally higher procedural memory (p = 0.03) and there was a significant interaction such that the children of anemic mothers in the multiple micronutrient supplementation group scored higher in general intellectual ability (p = 0.01). None of this would survive correction for multiple comparisons.

Zhu et al. (2018): 2,118 in rural areas of Western China were followed up at fourteen years of age after being randomized to either multiple micronutrient supplementation, folic acid supplementation, or folic acid plus iron. The overall effects on the WISC IQ and index scores were generally nonsignificant, always small, and excepting one case before multiple comparisons correction, marginal. The benefit of multiple micronutrient supplementation over folic acid only was 1.13 IQ points (p = 0.02), and it was 2.03 IQ points for the verbal comprehension index (p = 0.01), with no significant effects on working memory, perceptual reasoning, or processing speed. The benefit over folic acid plus iron was 1.37 points for fullscale IQs (p = 0.0045, the not-quite-marginal effect) and 1.71 points for verbal comprehension (p = 0.02). The authors tried to salvage these results by interacting them with maternal enrollment timing, but the result was yet more small, marginal, and sometimes directionally strange results:

A later systematic review of prenatal supplementation found no effect whatsoever of multiple micronutrient supplementation on general intelligence compared to iron and folic acid supplementation (d = 0.00, 95% CI: -0.06 to 0.07), nor any effect on verbal comprehension and language (d = 0.02, -0.13 to 0.16) or motor function (d = -0.02, -0.17 to 0.13). But, there was a marginally significant effect on executive function scores (d = 0.09, 0.01 to 0.17, p = 0.03). All of these effects were reasonably precisely estimated, and the intervention in question boosted birth weight somewhat while marginally reducing rates of stillbirth and small for gestational age, and reducing the risk of diarrhea, among some other potential benefits. Other reviews note effects on birth weights as well.

A review of associations between malnutrition in pregnancy plus depression and child behavior and cognitive ability showed limited—usually marginal or nonsignificant—evidence that either quantity made a meaningful difference in cognition assessed at various ages, not just in trials, but also in confounded cross-sectional associations.

In light of generally disappointing results from large trials with high-quality treatments and measurements, Devakumar et al. pronounced that a “large body of available empirical evidence has not shown that antenatal [multiple micronutrient supplementation] leads to health benefits in childhood, including for cognitive development. Although such benefits may be more subtle and may subsequently come to light, theoretical future benefits should not supersede empirical evidence. This lack of long-term benefits should [be] of concern for debates about scale up.”

Protzko reviewed the impacts of multivitamins, iodine, and iron supplementation in school-aged children, finding effects of 0.097 d (0.006 to 0.187; marginal), 0.531 d (0.394 to 0.668; very large), 0.032 d (-0.048 to 0.111; nonsignificant), respectively. The review also contained effect sizes for cognitive and musical training, and those yielded effect sizes of 0.151 d (-0.044 to 0.346) and 0.421 d (0.196 to 0.646), but the former should be expected to fade out and the latter hasn’t held up. For that matter, neither has the former.

Treating infectious disease also generally leads to similarly minuscule and marginal outcomes in both older and more recent studies. Even hookworm eradication in the American South only had dubious effects on schooling and earnings. In a recent review on the effects of developmental neurotoxin exposure, the meta-analytic effect of lead, mercury, organophosphate pesticides, polybromide diphenyl ethers, etc., was -0.38 d for males and 0.14 d for females; the result for males was marginally significant (p = 0.03) and the result for females was not significant (p = 0.33). A review on meta-analyses of prenatal iodine supplementation in pregnancy cited a meta-analysis of two trials that collectively found no effect on kids’ neurodevelopment.

I could go on listing trials and reviewing results for supplementation and dietary changes taking place at various ages, assessed different numbers of years out, in different parts of the world, but I think my point is clear enough. Where people are not affected by goiter or severe anemia or similar conditions, you should not expect nutritional interventions to have large effects. These conditions are bad, so it’s fortunate that they’re rare; unfortunately, their rarity means easy nutritional intervention isn’t likely to have a large effect on IQs.4

Allah Reveals the Power of Nutrition?

Islam has provided us with a piece of quasi-experimental evidence on the effects of nutrition that I think is worth mentioning5: Ramadan might lower IQs by up to about one point.

The evidence for this proposition comes from comparisons of school performance among huge samples of Pakistani and White British students in Britain, stratified by the month of their pregnancy that Ramadan took place in. Among the White British students, the month of pregnancy Ramadan took place in wasn’t related to test scores, and among Caribbeans, the same thing was true. But, for Muslims, scores were lower if their mother was pregnant during Ramadan, and maybe lowest at two to three months in.

During the month of Ramadan, people eat the pre-dawn meal Suhur, fast without food or water (sawm), and when evening hits, they eat the fast-breaking evening meal, Iftar. The idea behind this study’s apparently harmful effect is that sawm, meal irregularity, the unhealthy food people consume during Ramadan, some other factor, or a combination materially harms neural development through some route like malnourishment or stress.

The plausibility of this argument is not clear to me.

For one, the malnutrition angle seems hard to support. In this study, non-fasting mothers gained 11.26 kilos during pregnancy, compared to 11.25 among those who fasted 1-10 days, 11.21 for 11-20-day fasters, and 10.8 among 21-29-day fasters. These differences were only marginally significant (p = 0.04). This study found an increase in weight among both male and female fasters over Ramadan, meaning there was a positive shift in caloric balance. In this study, caloric intake increased by about 150 calories, while weights declined marginally (-0.3 kg). This study found a 20-calorie difference in total daily caloric consumption after starting Ramadan.

That last study had another interesting find: measurements of cortisol circadian rhythms were not very strongly affected by fasting.

More relevant to maternal health, this study found greater—and sometimes excessive—postprandial glucose levels among pregnant Muslim women who broke their fasts. That could be a source of stress. The study on pregnant women’s weight gain also reported a marginal reduction in gestational diabetes, but otherwise, nothing differed: not preterm birth, preeclampsia, birth weight, head circumference, Apgar score, etc. In this study, Ramadan wasn’t related to Muslims’ risk of preterm birth in general, but it was marginally related to the risk of “very” (28-31 week) preterm birth (RR = 1.33) for mothers who fasted at 15-21 weeks, and considerably related to very preterm birth (RR = 1.53) for mothers who fasted at 22-27 weeks (the wrong weeks to line up with months 2-3). For some reason, “extreme” (22-27 week) and “late” (32-36 week) birth rates weren’t affected.

A review of the effects of Ramadan fasting on pregnancy and offspring health outcomes reported that associations between Ramadan fasting and offspring health outcomes are not based on strong evidence. Another review concluded similarly, that Ramadan fasting doesn’t seem like it does a whole lot with regards to nutrition.

I couldn’t find anything specifically dealing with physiological stress during Ramadan fasting by pregnant women, but the lack of evidence just leaves the reasons to think that Ramadan will lead to extra physiological stress or nutritional inadequacy in the domain of intuition rather than empirical evidence.

One of the odd details about this whole thing is that the choice to fast is selective. Pregnant women are not required to fast, but as this and this study noted, many women aren’t aware of their exemption. Women exert some degree of control over the times they get pregnant, and there are cases of women trying to avoid holidays, so what if the apparent negative impact of Ramadan is due to pregnancy during Ramadan being selective?

In the Born in Bradford study, 128 out of 300 women fasted during pregnancy. The choice to fast was, evidently, selective. The choice to fast was related to obesity, being a mother who had never held a job, being less educated, and being in a consanguineous (inbred) marriage. In other words, there’s room for selection to explain this result.

If we take Born in Bradford as the ground truth regarding rates of Ramadan fasting among pregnant women in the U.K., then we’ll need to adjust the effect sizes from the study of Ramadan’s negative effect on test scores since identification of the effect was based on students being Pakistani, not surveying their mothers about their fasting habits. If 42% of women fast, the largest negative effect size (-1.05 IQ point-equivalents) goes up to 2.50 points, and that’s what we have to explain. If there’s a spousal correlation of 0.4 in IQs, at a heritability of 10%, we would need fasting mothers to have 35.71-point lower IQs to explain away the effect via selection. At 50% heritability, they would need to have 7.14-point lower IQs. That number seems downright reasonable given the observed educational and occupational deficits among fasting mothers. If we use the less extreme estimated effects, then the amount the mothers need to be selected by declines to be even more reasonable.

But there’s an argument against selection too. The differences in the effects of Ramadan by the month of the pregnancy might speak to something real, like a larger fasting effect during a relatively earlier, more critical period of development, or mothers being less aware of their pregnancy two to three months in compared to later, when they’d be less likely to fast. These are on the table, and if women really do have little control over pregnancy timing or desire to avoid Ramadan during it, then selection just doesn’t work as an explanation.

But on the other hand, the heterogeneity by month of exposure argument is statistically shaky. After all, the most extreme difference in the size of the effects between Ramadan-exposed months was not significant. There wasn’t really a statistical reason to think that Ramadan exposure in the second or third month of pregnancy is worse than exposure in the fifth, sixth, or seventh months.

If the downside of Ramadan is theoretically confined to a vaguely-defined effect of time spent fasting that isn’t due to effects on caloric intake, that makes the finding irrelevant to this article.6 Even if we wanted to humor the idea that Ramadan was bad due to malnutrition, we would run into the fact that malnutrition-derived intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is mostly of the asymmetric variety.

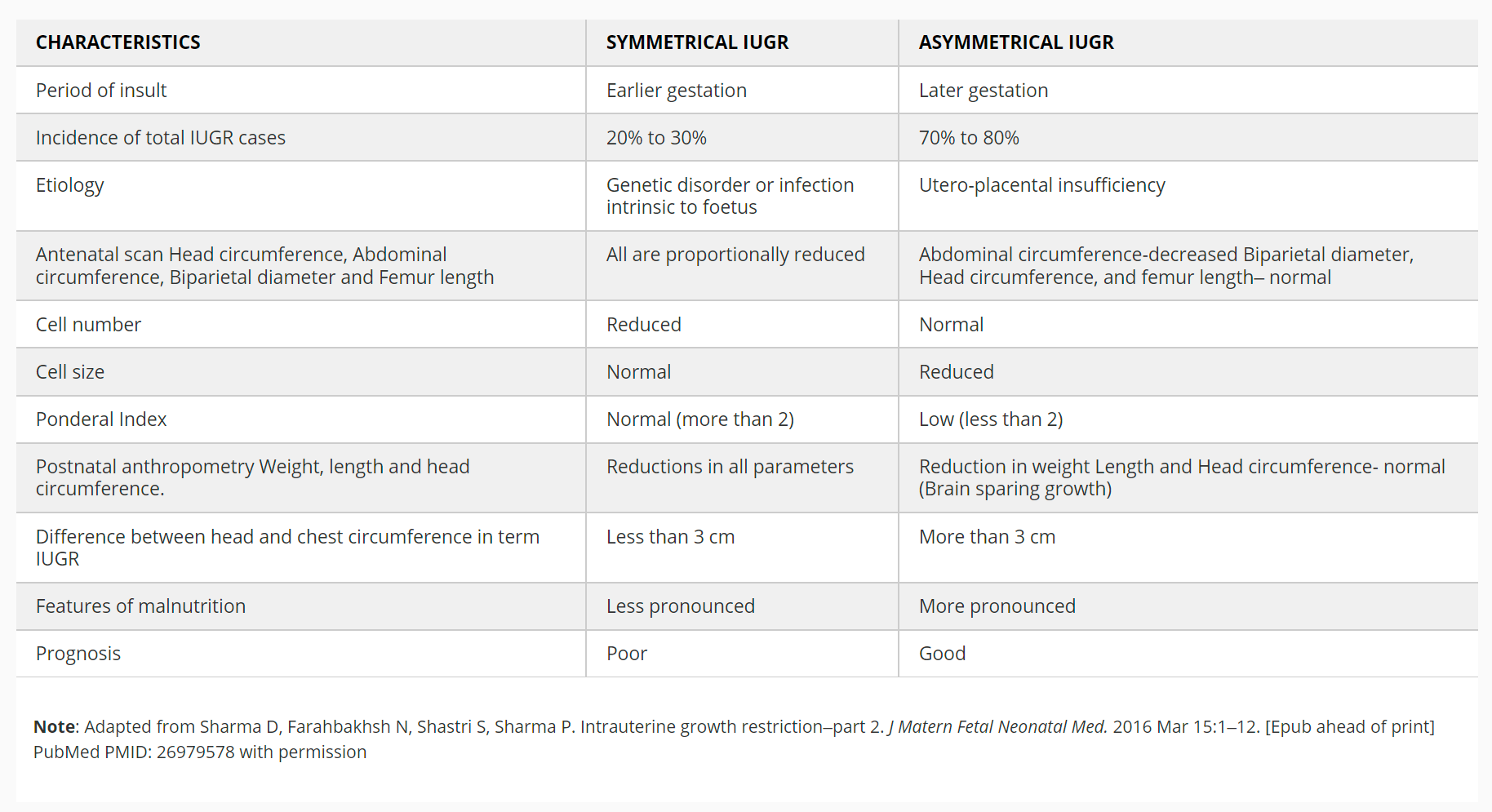

The three main types of IUGR are asymmetrical, symmetrical, and mixed. Asymmetrical IUGR is the most common variety, accounting for about three-quarters of all IUGR cases. Combined with mixed IUGR, symmetrical IUGR accounts for the remainder. The difference between the types of IUGR is in their causes and consequences. Asymmetrical IUGR tends to occur due to malnutrition, and it results in babies with smaller bodies, but normal-sized heads, because the body wants to spare the brain. Symmetrical IUGR tends to occur due to genetic issues or infections, and it comes with shrinkage of the body and the brain.

The type of IUGR that should be induced by Ramadan—if any—is the asymmetrical type that spares the brain. If it does that, then it’s not clear why it should have an effect on test scores down the line. Perhaps asymmetrical IUGR isn’t totally brain-sparing; if so, then presumably trials of prenatal nutritional supplementation should show IQ gains. But they tend not to. Presumably they should also show larger effects on height and weight. One of the only sibling control studies of this provided evidence on height and weight effects, showing basically nothing but noise, with the largest effect apparently being for Ramadan exposure for non-Muslims—a nonsensical result. If those variables are at best minimally affected, IUGR that impacts cognitive ability seems even less likely.

Presumably the already small effect I’m trying to explain would decline with a sibling control from its already minuscule size of less than 1 IQ point-equivalent outside of the most extreme results on the plot (-1.05 IQ point-equivalent).7

Since this study has produced a confusing result that we can’t be sure is real, I suggest testing it again. Since experimentally asking mothers to fast probably wouldn’t be able to slip by an ethics board, I suggest replicating the result at older ages, using a sibling control, and instrumenting with local Imam opinions on fasting desirability and knowledge of the pregnancy exemption. Comparing outcomes for different Muslim groups based on their adherence levels could also be a viable way to get an answer and a replication. Another method would be to track the kids of non-Muslim surrogate mothers to Muslim families—a group I believe will be vanishingly small.

So does Ramadan hurt kids? It’s not at all clear, but I have doubts.

Incredible Studies Versus Macro-Data

If you read old Krugman articles, you’ll notice he had a lot of reasoning tips, one of which was to reason with sanity checks. Someone would say something extreme, and he would go and check some basic statistic to see if what they were saying could even potentially be true. Take the time he fact checked Michael Lind’s writing on trade in Harper’s. Lind wrote:

Many advocates of free trade claim that higher productivity growth in the united States will offset any downward pressure on wages caused by the global sweatshop economy, but the appealing theory falls victim to an unpleasant facts. Productivity has been going up, without resulting wage gains for American workers. Between 1977 and 1992, the average productivity of American workers increased by more than 30 percent, while the average real wage fell by 13 percent. The logic is inescapable. No matter how much productivity increases, wages will fall if there is an abundance of workers competing for a scarcity of jobs—an abundance of the sort created by the globalization of the labor pool for U.S.-based corporations.

Now, at a glance, Lind’s argument might sound specious. As Krugman immediately noted, it was, and not only was it specious, it obviously was. He wrote:

Now what should Lind have done before publishing this passage? He should have had an internal monologue–something like this: “Hmm, do these numbers make sense? Well, historically, compensation of workers has been around 70 percent of national income. So let’s say that initially, output per worker is 100, and the wage is 70. Now if productivity is up 30 percent, that means that output is 130, while if wages are down 13 percent, that brings the wage down to around 61, which is less than half of 130–wow, that means that the share of labor in national income must have fallen more than 20 percentage points. Let me check that out in the Statistical Abstract. …”

Looking at the Statistical Abstract, the share of compensation in national income did not decline by 20 percentage points. In fact, it was virtually identical (about 73%) in both 1992 and 1977. Krugman continued:

How could Lind have failed to go through this little monologue? Well, I have had several conversations with impressive, highly articulate men, who believe themselves sophisticated about economic matters, but who simply do not understand that if productivity is up and wages are down, this must mean that labor’s share in income has fallen. These conversations are not pleasant: They want to discuss deep global issues, and end up being given a lesson in elementary arithmetic. But that is precisely the point: All too many people think that they can do economics by learning some impressive phrases and reciting some gee-whiz statistics, and do not realize that you need to think algebraically about how the story fits together.

Back to nutrition.

Researchers constantly make amazing claims about their ability to make the world follow their whims. In The Economist’s article on using nutrition to boost IQs, they featured several such claims. For example:

Dr Tania Barham of the University of Colorado, Boulder looked at the results of a programme of vaccination in the 1980s against diseases such as tuberculosis, which can affect nutrition and development. By comparing men who were eligible to be jabbed as babies with similar ones who missed out, she found that they were 30% likelier to have professional or semi-professional jobs at the age of 24-30.

Without a baseline, I’m not particularly impressed by this claim; with the paper in front of me, I’m even less impressed. The “30% likelier” has a p-value of 0.048. The treatment effect on men aged 31-34 for working in agriculture was an even more shocking increase of 80%, but somehow such a large increase only came with a p-value of 0.222. A composite measure of reading, writing, and mathematics skills supposedly increased by 31% (p = 0.089), self-employment went up by 38% (p = 0.073), and being a business self-starter increased by 48% (p = 0.048). There were more effects, all like this somehow—all just under the economists’ significance threshold of 10% or the standard 5% threshold. In other words, the evidence was entirely unconvincing, and all the more so because the treatment was more than what The Economist let on: it was not just vaccination, it was intensive child health services, family planning, and so on.

The Economist featured other unlikely claims too. Consider these:

If a fetus’s weight is below the tenth percentile, the child can expect to score half a standard deviation worse on all neuro-developmental measures—the rough equivalent of seven IQ points…. A study in Bangladesh found that the combination of malnutrition and inadequate stimulation common in poor families was associated with an IQ gap of a whole standard deviation (about 15 points) by the age of five.

Sorry, but which of these is true? How does malnutrition sufficient to render a diagnosis of fetal growth restriction (i.e., <10th percentile fetal weight) only cut IQs by seven points while mere malnutrition and “inadequate stimulation” during a less critical developmental period cuts them by twice as much? The scales of these effects don’t match up, and they’re not consistent with what we know about IUGR.

You might say the inconsistency doesn’t matter because the latter sentence contained the word “associated with” rather than “causes”, but these statements were preceded by the sentence “How much of a cognitive boost would the world get from feeding babies better?” That sentence means the ones following it should be interpreted causally. Fix the food, educate the mothers, and pump up those babies and you’ll gain 7? 15? Why not 30? IQ points.

If you believed even a tenth of the claims researchers made, you would be continually embarrassed by reality’s reluctance to conform with the research. The macro data simply does not comport with these studies.

Consider the article’s diagram on rates of stunting. In it, we see stunting in China go from about 20% to approaching 0%; we see Bangladesh fall from over 50% to just over 20%; we see Uganda somehow beating the Philippines to become a country with a bit less stunting; and we see Libya going from less than 20% stunted to over 50%!

If stunting is associated with very large IQ deficits, then where are all the new geniuses? Why haven’t most places’ IQs skyrocketed? Why aren’t we hearing about the Libyan mental retardation epidemic? Where’s post-Deng China II? With all the global progress, where are all the missing IQ points and why hasn’t the Flynn effect become real?8

The answer is that the magnitudes of the effects The Economist provided estimates for are simply wrong. The studies estimating them might be self-serving—everyone wants to boost IQs, eliminate suffering, and show that they were the ones to figure out how to do it—and they are certainly exaggerated. If you want to argue otherwise, then conduct a very large, wholly preregistered and independently analyzed trial. I have a feeling making that the standard will make outrageous claims untenable and discussion much more sane.

What Should An Issue On IQ Boosting Look Like?

The first thing a good issue on boosting global IQs should do is acknowledge the past. We do not need to set ourselves up to rediscover that phenomena like the Flynn effect are not signals of intelligence improvement, or that nutrition doesn’t explain the Flynn effect, or that trends in standardized test scores over time are usually artefactual. Having to rehash these facts impedes progress in discovering new ones that may be of actual use to us in boosting IQs.

The second thing is that it should be a call for research. By that I do not mean the same sorts of trials we’ve been running; what I mean are large, properly analyzed, theoretically motivated trials built off of solid literatures and powerful theories rather than rubbish about how passing out multivitamins will turn slums into von Neumann factories.

Ideally, what an issue on boosting global IQs should start with is what’s proven, and unfortunately, very little is. If we’re being technical and we mean intelligence rather than scores on IQ tests, then nothing is proven. That is the biggest problem for an issue on boosting IQs. Inevitably, because there’s nothing there yet, it’ll be an issue for what feels like it should be there; it’ll wind up being a venue for people to launder their hopes into other people’s policy motivations.9

It’s believed nutrition will have huge effects on not only intelligence, but practically every outcome, because it feels like it should. The feeling makes sense: nutrition is something many people have given a lot of thought to at some point or another, and many of those people have come to strong—typically poorly-supported—opinions on what works, how it works, and how more people should realize what they’ve figured out. But nutrition is messy, and what we can expect to gain from improving it probably isn’t so world-changing that it deserves a special report in The Economist.

Despite its lack of promise to enlarge our minds, we should do something about malnutrition in the developing world. Poor nutrition causes people to be born with preventable birth defects, it causes babies to die in the womb and in their mothers’ arms, and if it goes on long enough, people can die from what should be trivial diseases like the flu and diarrhea. We should improve nutrition because people suffering through starvation, hunger, and the illnesses of malnourishment is something bad that we can—and I think should—prevent.

In What Is Intelligence? Flynn also noted that

[Nutrition] is viable as a causal factor in only three nations post-1950. Even in those nations, it has merely escaped falsification….

Some take the fact that height has increased in the twentieth century as a substitute for direct evidence. After all, better nutrition must have caused height gains and if it increased height, why not IQ? However, the notion that height gains show that IQ was being raised by better nutrition is easily falsified. All we need is a period during which height gains occurred and during which IQ gains were not concentrated in the lower half of the IQ distribution. Martorell shows that height gains persisted in the Netherlands until children born about 1965. Yet, children born between 1934 and 1964 show massive Raven’s-type gains throughout the whole range of IQs. French children gained in height until at least those born in 1965. Yet, children born between 1931 and 1956 show massive Raven’s gains that were uniform up through the 90th percentile.

Norway has been cited as a nation in which the nutrition hypothesis is viable, thanks to greater gains in the lower half of the IQ distribution. Actually, it provides a decisive piece of evidence against the posited connection between height gains and IQ gains. Height gains have been larger in the upper half of the height distribution than in the lower half. This combination, greater height gains in the upper half of the distribution, greater IQ gain in the lower, falsifies the posited causal hypothesis: greater nutritional gains among the less affluent as a common cause of both greater height and IQ gains. US data are equally damning. Height gains occurred until children born about 1952. Fortunately, a combination of Wechsler and Stanford-Binet data gives the rate of IQ gains before and after that data, that is, from about 1931 to 1952 and from 1952 to 2002. The rate of gain is virtually constant (at 0.325 points per year) throughout the whole period—the cessation of the height gains makes no difference whatsoever. It is worth noting that there is no evidence that the ratio of brain size to height increased in the twentieth century.

Finally, the twin studies pose a dilemma for those who believe that early childhood nutrition has sizable effects on IQ. The differences in nutrition would be primarily between middle-class and poor families. Children who went to school with a better brain due to good nutrition would have the same advantage as those with a better brain due to good genes. By adulthood, the impact of their better nutrition would be multiplied so that it accounted for a significant proportion of IQ differences or variance. Yet, the twin studies show that family environment fades away to virtually nothing by adulthood. I can see no solution to this dilemma.

In the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth, there is also evidence that is shockingly inconsistent with the nutritional thesis. But also note: the gains on the test used in this study were substantially reduced correcting for test bias.

One thing Flynn said might be wrong in here though: brain size-to-height could be up, slightly, and seemingly not in some of the latest cohorts (at least at early ages), but not to a degree that would vindicate nutrition as a major source of Flynn effect gains. He became aware of that later.

If I had to guess, the earliest birth cohorts were undercorrected due to a lack of granularity in my measures and statistical power. I can’t fix that or provide anything like definitive evidence that it’s the cause, but it’s my suspicion, which I’ll also say should be coupled with potential cognitive decline among the very old as a source of discrepancy.

I think the failures of these interventions should help us to rein in claims about the IQ boosting effects of practices like breastfeeding and breastmilk use too. The relationship between breastfeeding and IQ is substantially driven by genetic confounding. Experiments and quasi-experiments tend to fail to support it having a meaningful effect.

The article’s findings could also be driven by something to do with seasonality, but I don’t believe that was really the reason.

There is a sibling control study on this topic, but it doesn’t include the information required to interpret it. Apparently exposed children did 7.4% lower on cognitive tests, 8.4% lower on mathematics tests, and were worked 4.7% fewer hours per week as adults, and they were somewhat more likely to be self-employed (which apparently might be considered bad in the study’s country, Indonesia).

“Real” meaning principally about gains to intelligence rather than psychometric bias.

I believe that, inevitably, such an issue will also end up being one on things that boost measured IQs through debiasing tests rather than through boosting people’s intelligence. The reason I think this will happen is that there are studies suggesting variables like education and air conditioning improve test scores, and that’s all we have, even though none of those studies show that anyone was actually made any smarter.

Some of the smartest people i know have the pickiest insane babies that practically malnourish themselves from birth despite every sound intervention. Stubborn infants. They don’t seem to be the worse for it long term.

Also, down with most nutritional “science” lawl.

In countries with universal conscription, there should be, buried away somewhere in the Ministry of War, decades of data on hat/helmet sizes. Granted, the correlation between IQ and external head size is quite low, but it would be interesting to know whether heads are getting bigger.

Also, did the introduction of Caesarean baby deliveries lead to more people with bigger heads?