Intelligence and Social Mobility

People who outclass their parents, siblings, or social class tend to move up. The outmatched tend to move down.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

A brilliant child born in a poor family tends to move up into a higher social class; a dull child born in a wealthy family tends to move down into a lower social class. These facts may seem obvious, but surprisingly many people don’t appreciate or incorporate them into their world models. To that end, simply documenting and making those facts apparent might help some people to fix up said models; it might help prompt keeping these facts in mind, avoiding errors that may arise if they forget them.

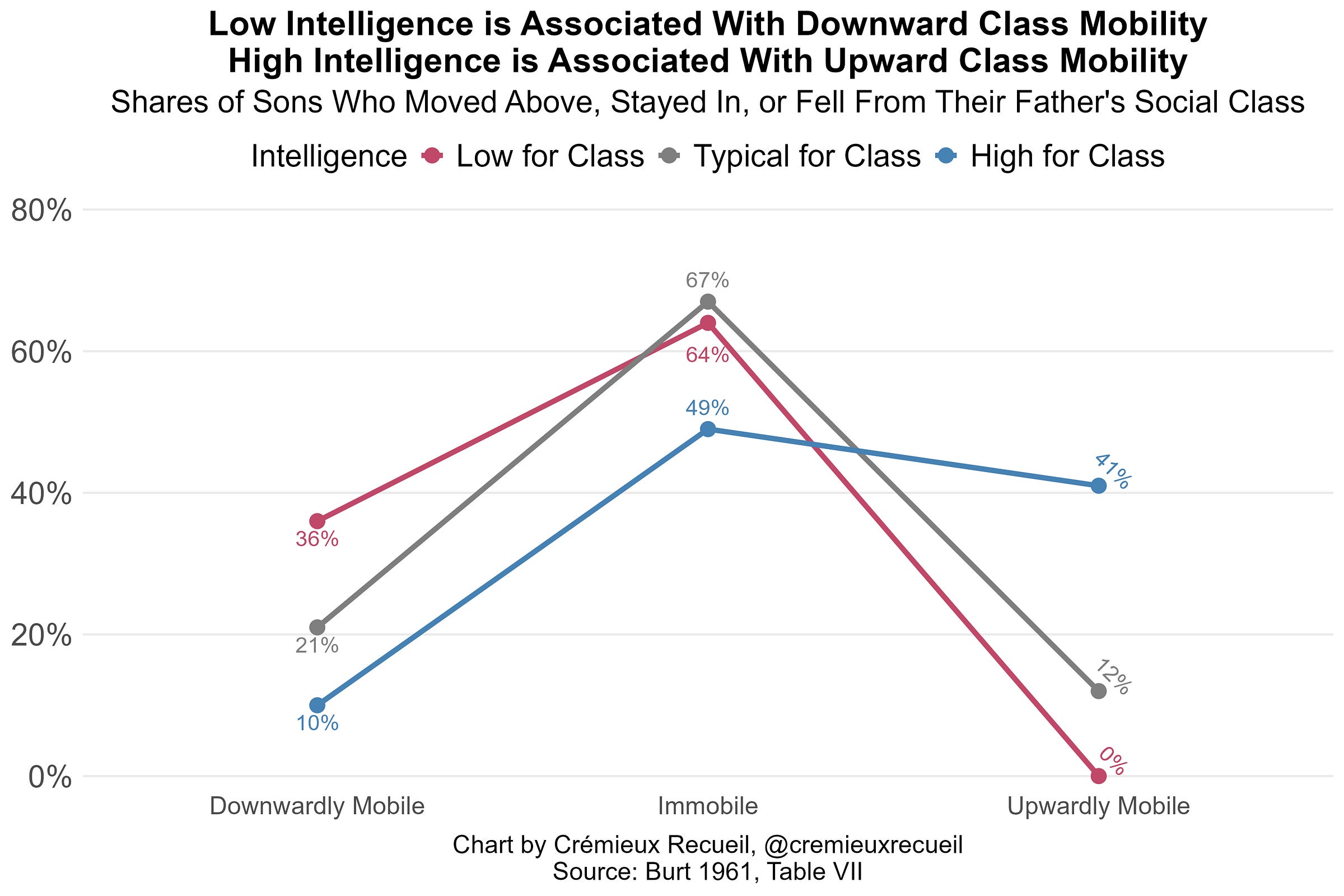

These facts have been documented for a very long time. For example, Cyril Burt (1883-1971)1 noted in 1961 that Britons who had relatively high intelligence for their social class tended to either stay in their class or move up, and those who had relatively low intelligence for their social class tended to stay where they were or move down.

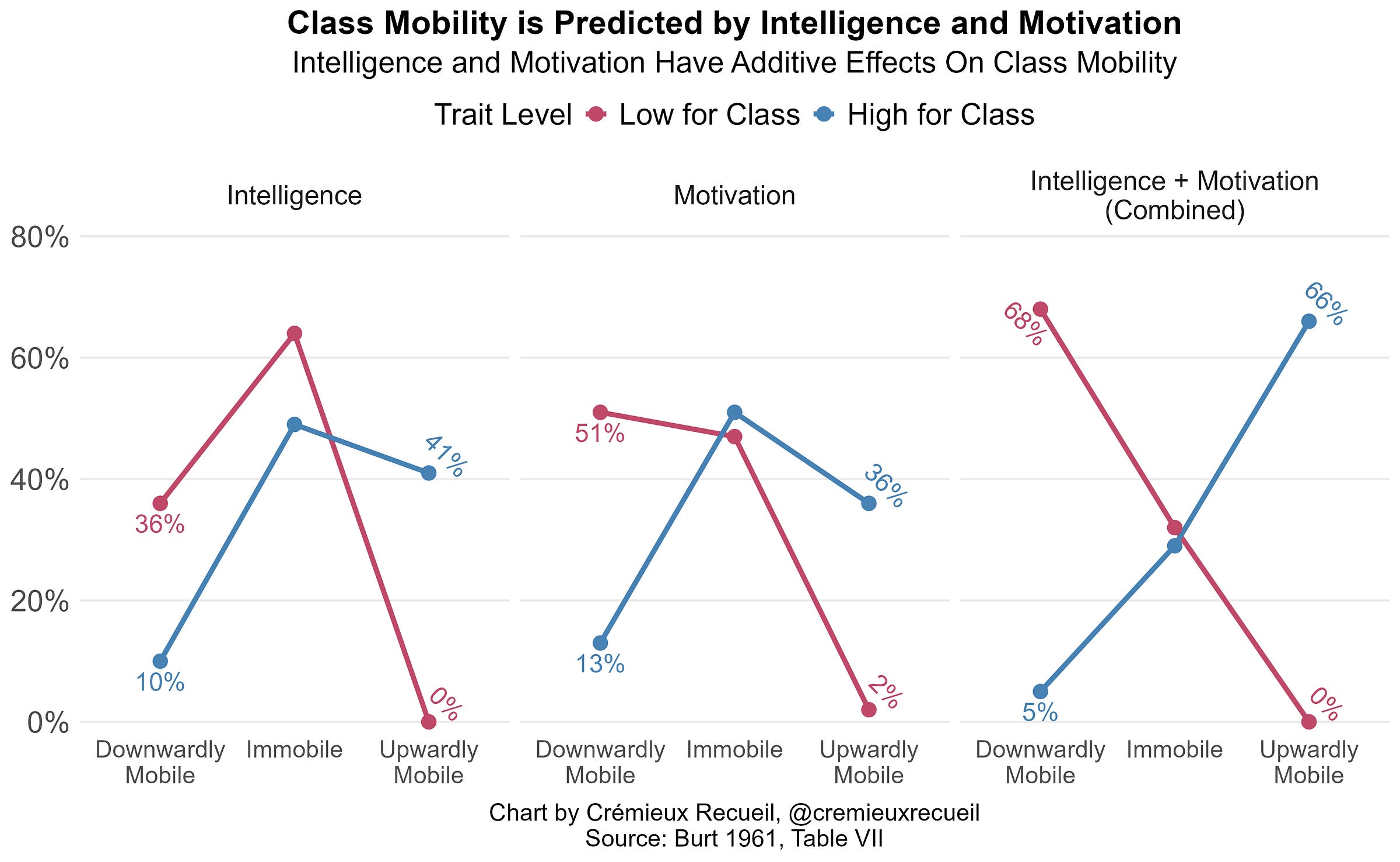

Burt didn’t neglect other factors like home background, educational achievement, or motivation. In fact, he documented a number of facts related to the simultaneous influence of these factors. For example, he noted that taking both intelligence and one’s motivation to succeed into account, about two-thirds of those high on both moved up, and two-thirds of those low on both moved down in social class.2

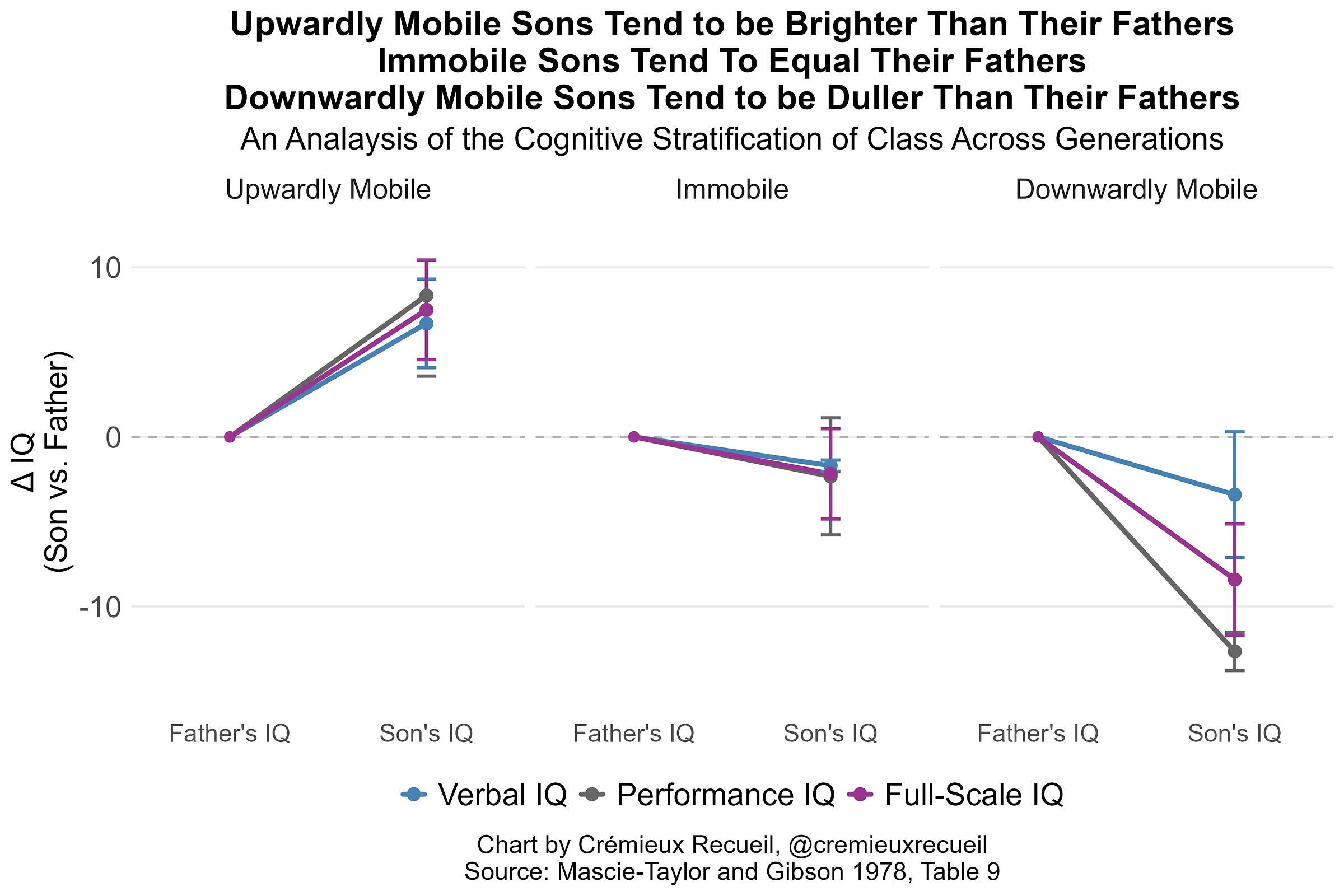

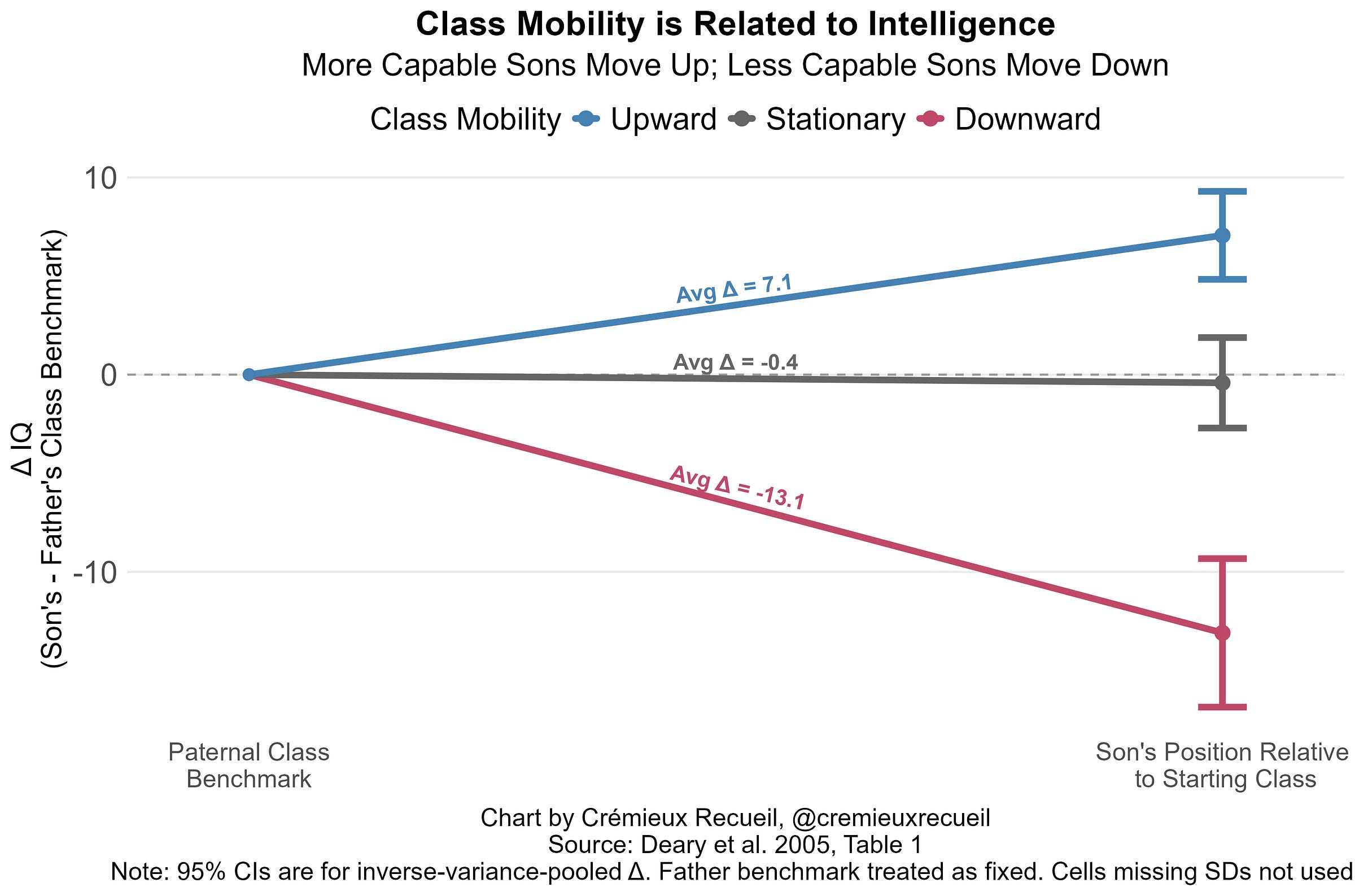

Mascie-Taylor and Gibson replicated this result with other British data, showing, for example, that individuals who were upwardly mobile tended to have higher IQs than their fathers, whereas those who were downwardly mobile tended to be less intelligent than their dads.3 As you might expect, those who remained in their dad’s social class were about as smart as their fathers.

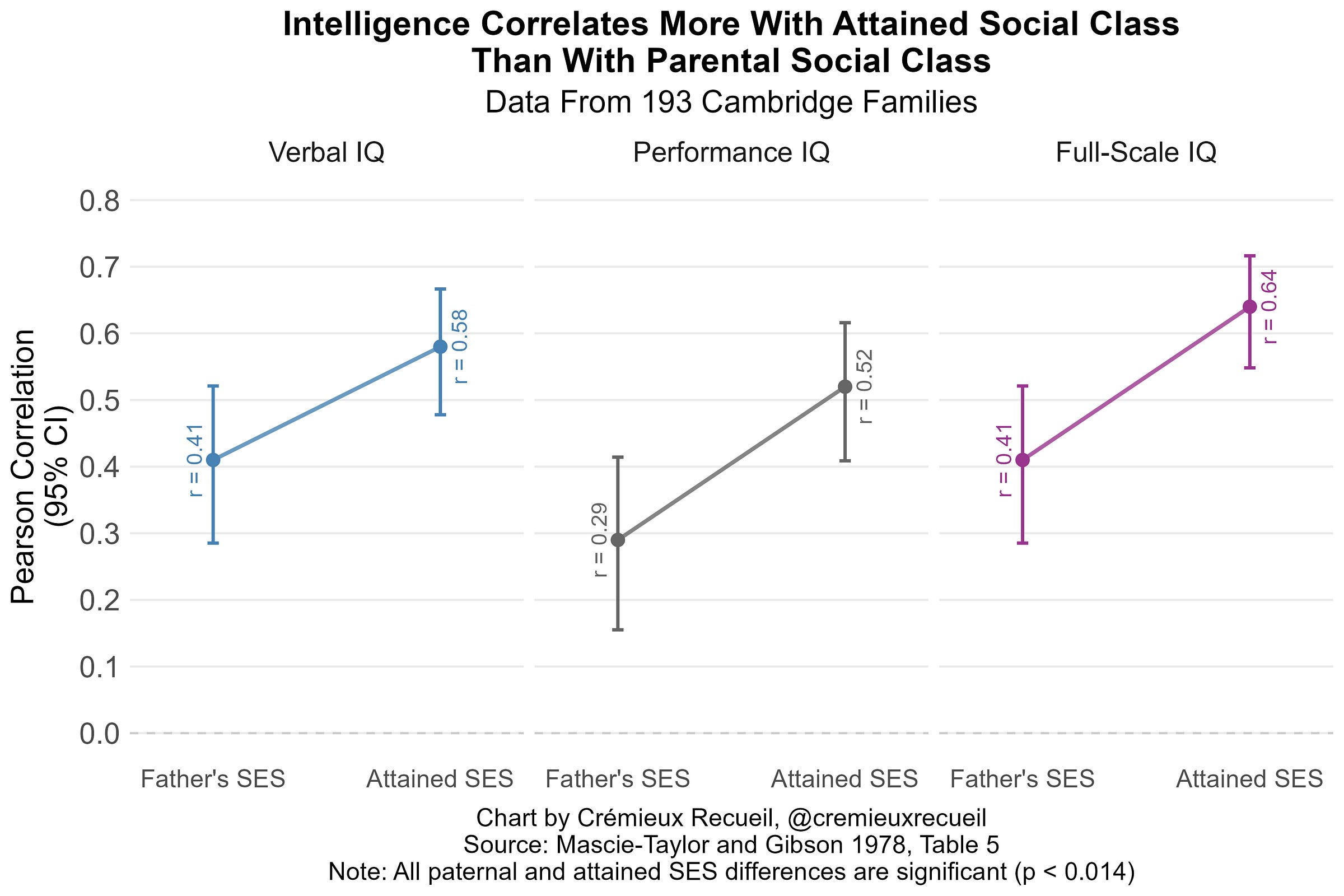

A corollary of these findings is that, as Arthur Jensen noted in The g Factor, individuals’ attained (i.e., earned, final, present, etc.) socioeconomic status is more strongly correlated with their IQ than is the socioeconomic status of the household they grew up in. Mascie-Taylor and Gibson found support for this notion:

In more recent data, Deary et al. observed that these findings have held up. For example, they noted that the upwardly mobile tend to outmatch the people in their social class of origin, whereas those who are downwardly mobile tend to do worse, and those who don’t move tend to be about where their origin class is, intellectually.

These results replicate in non-British cohorts and with other types of relationships than fathers versus sons, too. When IQ predicts mobility within sibling pairs, for instance, that means the more gifted sibling tends to move above the less gifted one, and the less gifted siblings tend to end up in a lesser position than more gifted ones. Therefore, whenever you see the IQ-success relationship in a sibling control study, you’re seeing a replication. We see this in studies like the Kalamazoo Brothers Study (Olneck 1977), in large-scale Swedish register data (Sandewall, Cesarini and Johannesson 2014), in large-scale Danish register data (Hegelund et al. 2019), in the National Longitudinal Surveys from 1979 and 19974, in Minnesota (Willoughby 2020)5, and in virtually all other large, high-quality samples from the developed world.

Where civilization is concerned, ability-driven social mobility is the rule.

Some studies make efforts to quantify the degree to which initial social class modifies opportunities for mobility. In both the U.S. and Britain, researchers have found that there’s “no evidence that those from underprivileged backgrounds have to be disproportionately able in order to reach the professional classes.” Various studies have suggested the existence of a glass floor. This floor makes it so that downward mobility from high classes is attenuated. This has not been universally supported, however; as that U.S. study noted: “parents’ education level did not moderate the association of offspring skill with social mobility.”

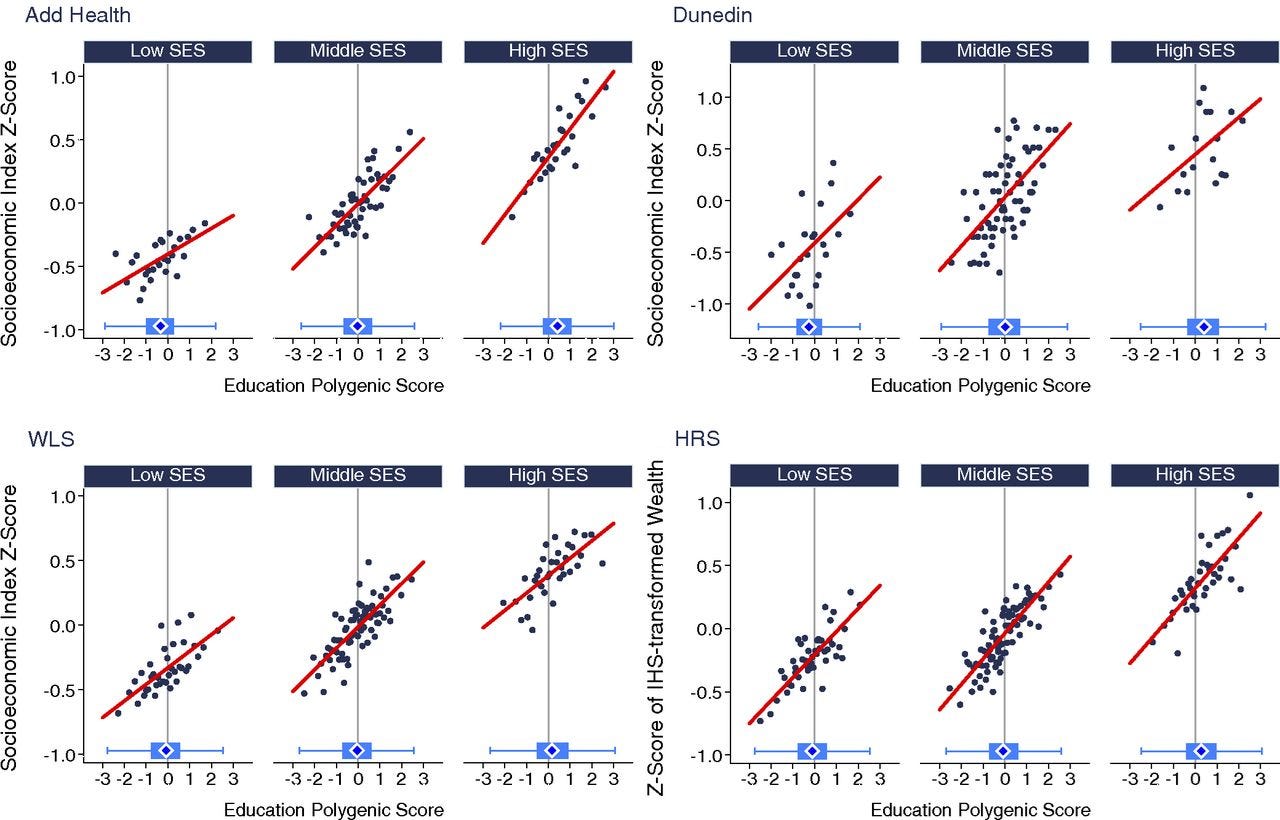

The social part of the transmission of cognitive and noncognitive phenotypes across generations has been found to be limited. The same has been observed for the resulting socioeconomic measures as well. In contrast, it’s frequently noted that there is a substantial genetic element to society’s stratification. We can directly view that by looking at polygenic scores in different studies. Consider this result, and take note that it holds up between siblings, and it holds up such that kids who have higher polygenic scores than their parents tend to move up.

Social context can readily modify the heritable part of mobility. For example, greater equality of opportunity means higher heritability for educational attainment and higher single-generation social mobility might be related to higher educational attainment heritability too. More interestingly, there’s evidence that social systems like communism can suppress the heritability of socioeconomic class, and that the fall of communism is associated with an increased role for genetics.

An even more interesting finding is that environmental sources of success can lead to genetic stratification. In this brilliant paper, the authors used biobank data from Britain and Norway and found that birth order effects—which are environmental in origin—are transmitted genetically. The way this happens is through helping people to get a higher-quality spouse, who will tend to have better genes:

It is known that earlier-born children receive more parental care and have better life outcomes, including measures of SES such as educational attainment and occupational status. On the other hand, all full siblings have the same ex ante expected genetic endowment from their parents, irrespective of their birth order. This is guaranteed by the biological mechanism of meiosis, which ensures that any gene is transmitted from either the mother or the father to the child, with independent 50% probability ... We can therefore use birth order as a ‘shock’ to social status.

And

Our empirical analysis shows that in Great Britain and Norway, two contemporary developed countries, earlier-born siblings had spouses with higher [polygenic scores for educational attainment]. We also provide evidence that these effects are mediated by socio-economic status, specifically income and education.

What this means is that, because they end up higher class due to the environmentally-mediated benefits of being born earlier in the birth order and people sort into marriages by class, older siblings are able to obtain a genetically higher-quality spouse, a spouse that has higher-quality genes so that they end up in the same class position. The reverse can be true too. Or, in other words, people can environmentally compensate (be faulted) for (despite) a bad (good) roll of the genetic dice, and their kids can end up with better (worse) genes as a result.

Social mobility is related to individual abilities—meritocracy!—, and it has existed in many societies, for a very long time. Given that it should be present because being smart and hard-working is generally advantageous, it is no surprise that when we have good data, it is. Keep these facts in mind when reasoning about the world:

Meritocracy is real. Talented people move up and dullards move down.

Existing meritocracy is good in the developed world, but it’s also imperfect.6

Skills correlate more with where people end up than where they’re from.7

Some societies foster meritocracy more than others.

Meritocratic skill stratification has a substantial genetic basis.8

With freedom, meritocracy is ubiquitous. It is likely to some degree inescapable.

If you naïvely deattenuate by a reliability of 0.80 for both measures (the real reliability coefficients are likely somewhat lower for both measures, so this is conservative), the gaps get about 1/sqrt(0.80) = 1.118 times larger.

Thus, for intelligence, low for class goes down 37% of the time and is immobile 63% of the time whereas high for class goes down 8% of the time and up 43% of the time. For motivation, low for class goes down 53% of the time and is immobile 47% of it, whereas high for class move down 11% of the time and go up 39% of it. For their combination, those who are low for class go down 69% of the time and are immobile 31% of it, and those who are high for class go down 1% of the time, are immobile 29% of it, and go up 70% of the time.

As in other studies, this study also showed that the larger the difference, the greater the relative mobility. That is to say, people with somewhat higher (lower) IQs than their fathers move up (down) less than people with much higher (lower) IQs than their fathers.

Because the raw data from these studies is available, they’re the most readily available evidence for the noteworthy position that measurement error attenuates results like these. Using latent variable models in the NLSYs makes within-sibling relationships stronger, enhances the apparent cognitive stratification of socioeconomic status by ability, etc.

A good example of meritocracy being very good is that Blacks and Whites, matched for intelligence, end up with the same socioeconomic status in the U.S. For more on this, see here.

I added this link on December 2, 2025.

And where equality of opportunity is higher, class tends to be more heritable. This would not be true with equality of outcome for the obvious reason that it means outcome variance compression. Variance compression also means that meritocracy produces relatively less extensive stratification, but it may do nothing to the rate of mobility in relative terms.

I'd love to see a post sometime on how you do the timed posts - do you start with an idea? some preliminary research? all the research? What topics have failed to make the time limit? Do you ever revisit them? Etc. The process sounds fascinating. It could even be a "meta-timed post" as in a timed post about timed posting.

Excellent article. I especially liked the section on meritocracy. I am a firm believer in meritocracy.