The Making of an Elite: Japanese Christians

Why are Japanese elites so likely to be Christian when Japan is a 99% non-Christian country?

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than two hours to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

If people like the idea of articles describing elite group formation, I will continue to do more of these for different groups. You can find two of my earlier articles on this topic here and here.

Christianity in Japan is a story in two parts.

The first took place with the arrival of Jesuit missionaries in 1549 and lasted for nearly a century before the religion was banned and its adherents were forced to convert or hide their faith. In that time, Christianity reached its peak popularity, with almost 300,000 Christians in a population of 15 to 20 million. That story has been amply covered elsewhere if you’d like to go learn more about it.

My focus is on the less well known second period that’s taken place after the United States forced Japan to open up. This is the period in which Christians became one of Japan’s little-known elites.

It’s probably surprising to hear that 20% of the post-World War II Prime Ministers of Japan before the newly-elected Sanae Takaichi have been Christian. Out of those 35 Prime Ministers since 1945, Shigeru Yoshida and Tarō Asō were Catholic, and Tetsu Katayama, Ichirō Hatoyama, Masayoshi Ōhira, Shigeru Ishiba, and Yukio Hatoyama were various flavors of Protestant. How this happens in a country that’s less than 1% Christian and in which there’s significant anti-Christian discrimination is perplexing, but I think it makes sense given how today’s Japanese Christians came to be.

The most comprehensive history of this group is contained in three chapters written by sociologist Fujio Ikado, in which he details the rise of Protestant Christianity in Japan between 1859—five years after Commodore Perry opened it up—and 1918.

When Japan opened up, the country was hesitant to tolerate Christian missionaries. Accordingly, missionaries were obliged to live in cities and they were, for a while, restricted from actively proselytizing. As a result, their earliest converts were almost entirely people living in urban areas who primarily encountered Christian language and mission schools rather than preaching, helping to cement the initial stock of Japanese Christians as city-dwelling and—given the rarity of literacy—intellectual.

The next major boon for the character of early converts was the Meiji regime’s dismantling of the Tokugawa era class order. Between 1869 and 1876, the historical upper class—the samurai—lost their feudal domains, became subjects of the new central state, lost their guaranteed incomes, and were forbidden to wear swords or display status insignia like the topknot hairstyle. Newly jobless, these men and their sons had to find ways to preserve the status they had become used to, so they turned to formal, Westernized educations of the sort offered by missionaries.

This had a substantial effect on the composition of missionary schools. Via Ikado:

The first Christians were students of the language schools… and almost all such students were from among the jobless samurai.

And:

A majority of the student body of Dōshisha was comprised of those who had transferred from a Kumamoto language school established for young samurai of the Kumamoto clan.

And:

Almost all the Christian leaders who studied in the mission schools in Yokohama were the children of samurai.

And perhaps most critically:

Even though almost all of them at first gathered around the missionaries in order to receive English instruction, their enthusiasm for everything new was a sign of their intelligence. It also demonstrated their suppressed, critical, and irritated feelings. In other words, in their courageous opposition to government regulations and in their confession of Christianity, they were sustained by their wounded pride. For except in their intelligence, the samurai were no longer the superior of the common man. In many cases conversion came to those who were disappointed in both the past and the present. They were looking for a new ideal which would never betray them.

It is significant that the early Christian leaders with very few exceptions appeared among the samurai of those clans that had opposed the Imperial forces. Most of them were called “Meiji Puritans” and it is easy to understand why they got the name. Professor Saburo Ienaga has pointed out that the samurai Christian’s ethical demand was so rigid and extreme that it raised a wall between the masses and Christianity…

The conversion of many samurai undoubtedly resulted in part from their resentment against social change. Their consciousness of being “the Chosen” was to some extent an expression of a desire to assert their superiority as intellectuals over the common people. Thus, in their early history, a kind of ascetic ethics combined with a sense of superiority drove them as Christians into a state of isolation from the rest of society. As Dr. Hiromichi Kozaki pointed out, many samurai had joined Christian churches as a means of demonstrating their resentment against the new society. And, it was their resentment that caused them to move from a simple and sincere confession of sin to a defense of a pure Christian faith free from idolatry, and to oppose the government’s abuse of religion in its policy of modernization.

The disaffected samurai sought out foreign knowledge and encountered foreign faith. The most courageous among them adopted that faith and became more zealous adherents than the most fire and brimstone of the missionaries could have predicted, helping keep Japanese Christianity an elite affair, walling it off from the masses.

In 1872, the imperial government declared its plan for universal education. By 1880, they had reached 41% attending schools, but by 1890, they had only progressed to 49%. The problem with their goal was a lack of resources. There simply were not enough personnel available to fulfill the country’s educational demands while simultaneously expanding its bureaucracy, fostering its industry, and developing its army. This coupled with a few other facts in ways that pushed numerous would-be elites into, or at least compelled them to be favorable towards, Christians.

For one, the government required knowledge of English to attend universities. If you weren’t able to attend a government-run preparatory (middle, high) school because of the lack of slots or teachers, but you still wished to obtain one of the many new high-paying and high-status degree-gated positions the government was creating, you would likely end up going to one of the mission schools. This greatly pleased the missionaries and the university professors who were, incidentally, disproportionately foreign, Christian, and for obvious reasons, disposed to favoring Christianity.

In the heavily Christian environment students were being brought up in, the missionaries, the professors, and the zealous converts in the student body managed to turn thousands of students towards their faith. Once baptized, few converts reverted in this period, and once educated, they tended to rise through the ranks of society.

The second fact that helped the missionaries was that the state’s education drive began inadvertently funneling yet more of the country’s future cognitive elites into contact with them. The government instructed local officials across the country to begin finding their most capable students and sending them to the country’s urban areas so they could study. This meant contact with Christians at the preparatory level, and because of their overrepresentation at the higher levels of education, it obviously also meant contact there, allowing the Christians to net yet more talented converts. This was an especially good method of bringing these kids into the faith because the mission schools were in a “unique position as boarding schools.” In other words, if these talented kids from the boonies wanted to get an education, they were practically guaranteed to get a Christian one.

The third fact was not good for proselytizing efforts, but it was good for keeping Christianity elite. This fact is that the government actually started succeeding at building its own, non-Christian schools. By 1900, 82% of kids were enrolled in schools. Boarding schools became less commonly used since people traveled less for preparatory education, and in general, necessary contact with Christians declined.

The resulting decline in the pace of conversions of educational and cognitive elites was something missionaries expected, since they knew of the government’s plans to use mission schools as stepping stones while they built replacements. Nevertheless, that was good for Christians staying elite because it meant less dilution of the pool of potential converts. The kids sent from rural areas to urban centers were likely the most qualified of that pool of children, and as more and more kids would be sent, their quality would probably begin to decline for tautological reasons. Picking from the crème de la crème meant taking in those whose offspring would be less likely to regress to a low level. They would regress but they had a high level to fall from.

Thus, modern Japanese Christianity was established as a refuge for Japan’s dispossessed intellectual class and, to a smaller extent, as a welcoming faith for the first crop of distinguished and capable youths plucked from the nation’s countryside and brought to its rapidly developing urban cores in order to bolster the pace of development. This is a good start, but there’s still more to this story.

Before discussing the continued development of Japan’s Christians, I want to detour through a discussion of the samurai and the less familiar Kazoku.

I take for granted that everyone has heard of and understands what the samurai were as a class. The image of an ancient warrior-elite is accurate enough, but it should be supplemented with the knowledge that samurai were also frequently poets, civil administrators, police, regional rulers, bureaucrats, tax collectors, messengers, instructors, and so on. These jobs may not all sound distinguished, but they were far better than doing farming, which was the chief occupation for more than 90% of Japan prior to its modernization.

The Kazoku, on the other hand, were a more recently established class of elites. The Kazoku were created in 1869 and initially included 427 families, with the leaders of the Satsuma and Chōshū domains among them. The Kazoku merged daimyō (feudal lords) and kuge (court nobles) in order to create a state-managed, loyal nobility that would bridge the old feudal elites and the imperial court and legitimize the modern imperial state. With time, their order was expanded, and eventually the membership included 1,011 families who had entered by distinguishing themselves in the service of Japan.

The samurai were an ancient elite and the Kazoku were, by the time of their disestablishment, mostly recent, joined by a throng of families that had distinguished themselves in a single generation. This situation is thus analogous to comparing people who have high ability with high reliability (samurai) and people expected to regress to the mean (Kazoku) because they’re selected on the basis of an extreme observation. That is exactly what we see when we examine their descendants!

Remember how 20% of Japan’s post-World War II Prime Ministers before Takaichi were Christian? Shigeru Yoshida, Ichirō and Yukio Hatoyama, Tarō Asō, and Shigeru Ishiba—five of the seven—descend from samurai, some of whom could be confirmed to have been among the initial batch of Christian converts.

The exceptional Christian Prime Ministers were Masayoshi Ōhira—who converted of his own volition at sixteen after a near-death experience with typhoid fever—and Tetsu Katayama—whose father was a lawyer numbering among the white collar, second-wave converts. Those second-wave converts are the relevant ones for a discussion of the next phase in Japanese Christianity’s story.

Second-wave converts made Japanese Christianity less elite compared to when it was populated primarily by samurai, but they nevertheless maintained the religion’s significantly white collar character. The reason for the change has to do with Japanese nationalism.

The Japanese government had cultivated a sense of nationalistic pride under its “Rich Country, Strong Army” policy. They did this through educating the populace, propaganda efforts, and so on, and they succeeded in instilling an urge to show the western powers that Japan was a strong and capable nation. They also sought to redress the unequal treaties they had been subjected to, and they figured this would be a natural result of developing and distinguishing themselves as a civilized nation. As students of history, we know that this was not something the Japanese were able to achieve, and failure enraged the newly-nationalistic commoners.

The government’s response to the population’s rage was to take whatever measures they could to save their pride and sate the people. This meant doing what could be done to shake off the inferiority complex they had developed against the west and attempting to reassert their cultural uniqueness, the duties of the populace, and the capabilities and role of the government and the emperor. For example:

Thus, in promulgating the paternalistic constitution in 1889 the natural rights of man were repudiated. It was said that the Emperor graciously bestowed the franchise on the nobility and commoners but that it was not at all their right as individuals. Under this constitution freedom of thought and belief was granted on the condition that it was “not prejudical [sic]to peace and order and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects.” In other words, the Constitution was implemented to re-establish the family ethics which had been weakened in the period of Westernization.

In this environment, Christianity and its liberalism- and universalism-promoting schools were made to suffer. Education (and so much else) was to serve the state.

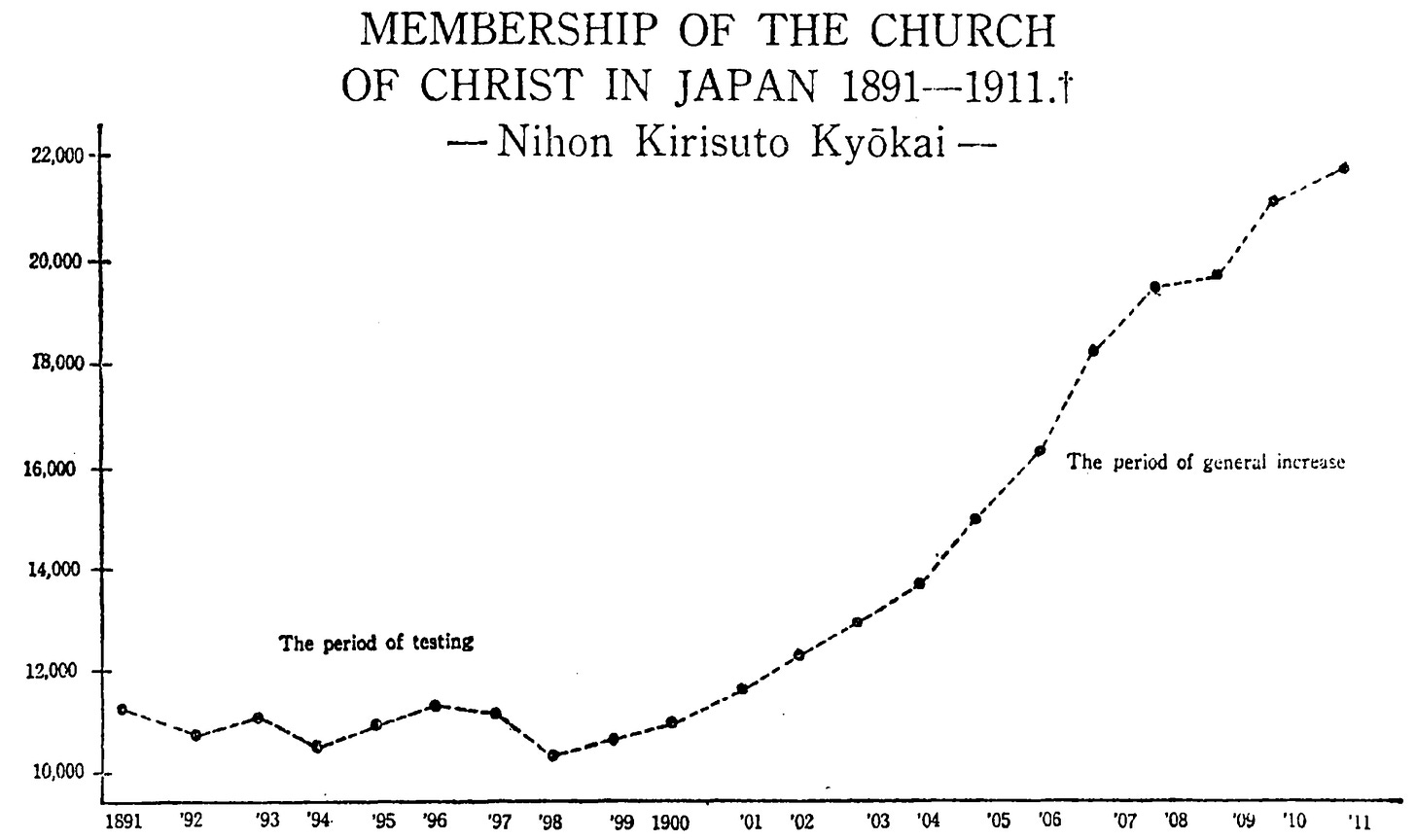

As the state pushed students away from Christian schools and towards its own, the primary source of new converts dwindled. Moreover, the most capable students stopped seeing Christian schools and the acquisition of faculty with English as means to obtain a high-status career. The priests and other missionary staff failed to adapt to this new normal and in the “period of testing” church membership barely grew. But slowly and surely, the church did adapt, and membership numbers lurched upwards as priests ascertained that the Japanese still had an interest in some of their services. Namely, the Japanese wanted kindergartens, Sunday schools, and extracurricular opportunities like the ones offered by the YMCA, Christian Student Association, and Christian summer schools.

The nature of the white collar class that was exposed to the church through these efforts was distinctly different from the earlier samurai converts. These people had no reason to resent the government, and they were a far more docile group as a whole than the warriors who came before them. They obtained educations and partook in Christian ceremony out of interest, curiosity, and in general, with far less purpose.

To actually gain membership, the church recognized that it has to keep working at its strategy. This meant hiring Japanese to run schools now that such people were available, and it also meant attempting to conform to the government’s rules. Many schools did come into compliance with the government’s regulations and they were recognized, but while this worked for a while, it left the government incensed as they did know the ultimate purpose behind the actions of the missionaries. So, after they had enough, in a fit of anti-Christian and anti-samurai furor, they issued Order No. 12 and banned religious practices in the schools, once again curtailing Christianity’s rise.

It was only some time after achieving a revision of the unequal treaties and showing that it could best Russia that the Japanese decided they were confident enough in their culture and their government and their rising power, that they could take their foot off the necks of the missionaries. But though the schools could proselytize again, they didn’t find much success in doing so. Instead, they looked for ways to engage youths in government schools in extracurricular programs: student movements, clubs, and so on. These attracted many Christians and non-Christians alike, and in time Christianity’s numbers were blooming, but church attendance on the other hand was meager by comparison. This batch of converts was effectively just nominally Christian.

As Japan grew wealthier, the new middle class growing in the urban districts began to use their money to attend Christian schools because they still offered superior instruction, and many kids converted during their time there. But, by the end of their educations, missionaries often found that they could not contact those kids again because they had simply become bored by Christianity. They had their fill in school. Or, stated differently, as Christian numbers grew, religious fervor declined in tandem, and attachment to the church followed with it:

[W]hile Christianity had helped modern education create the people called the white-collar class, in the process Christian activities had been narrowed to the limits of the social character of the salaried people who formed the core of the modern Christian community… Dr. Pieters summed up the situation as follows: “the results of Christian education are disappointing in the following particulars: in the fewness of graduates, considering the number and equipment of the schools and the length of the time they have been at work; in the failure to influence to a deep religious conviction such a large portion of the students; in the unsatisfactory character of so many who profess conversion, and in the fewness of candidates for the ministry.”

As time went on, the country modernized, and Christianity blended more and more into the background of Japanese society and white-collar life. Eventually, the church began to work with the government alongside leaders of other religions, in order to promote nationalistic control over religious and secular liberal movements. The church, through the change in its membership with the second wave converts, had become inhabited by a tendency to conform rather than the zeal, heroism, and ethical stalwartness displayed by its earlier samurai members.

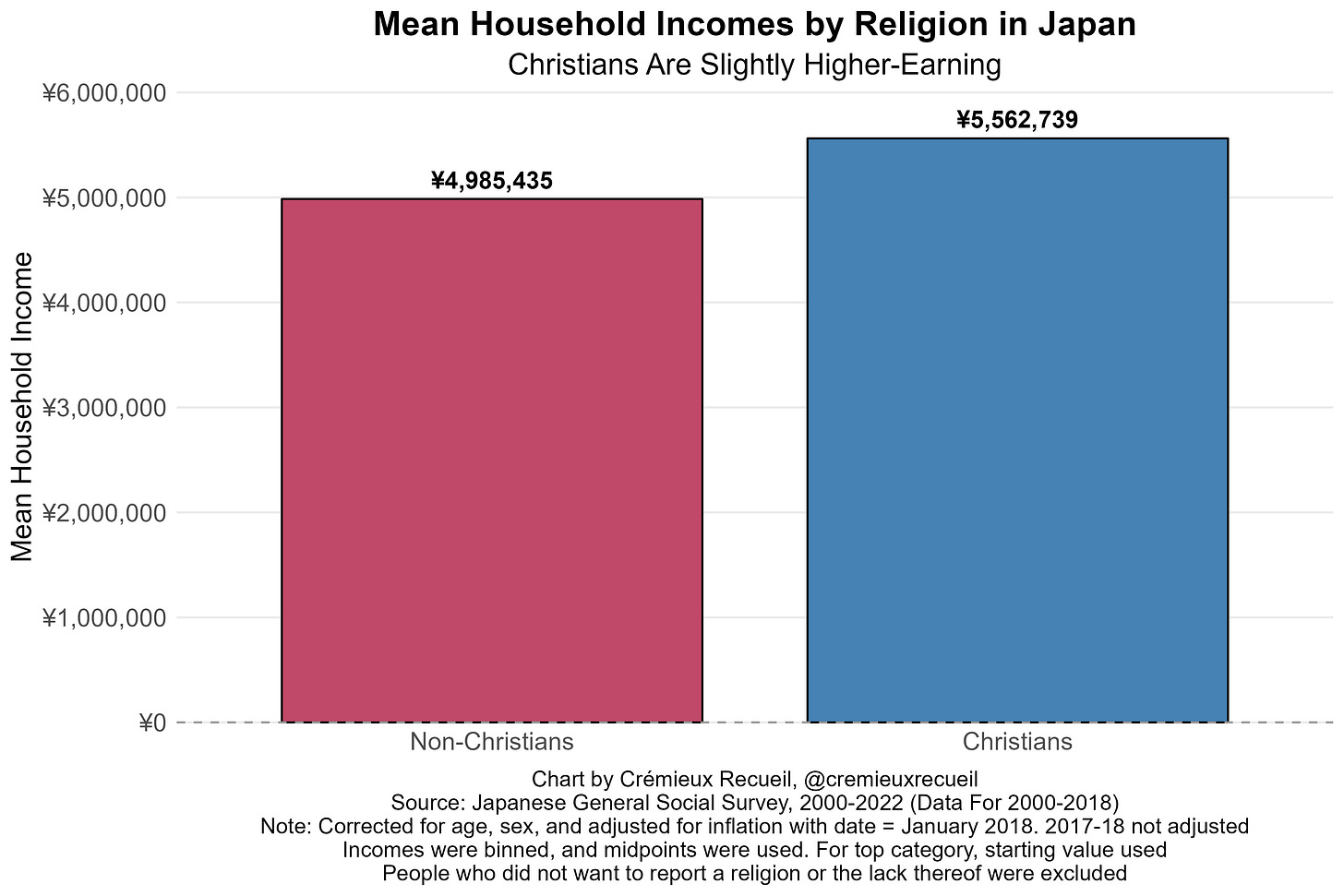

Today’s Japanese Christians have carried forward the urban and educated character that marked their early modern days. Their success is reflected in somewhat higher earnings compared to their non-Christian peers, even though Japanese society still significantly discriminates against them and several newer and distinctly non-elite Christian denominations have cropped up in more recent years.

More evocatively, the success of Japanese Christians is reflected in their overrepresentation in elite positions (like Prime Ministers) and at elite schools and universities. All of this seems to be the case less because Christians are distinct from the rest of the Japanese these days in terms of how they act—they now largely attend the same schools and whatnot—and more so because of how the group was formed.

The core of modern Japanese Christianity was an assemblage of the nation’s ancient warrior scholars. These individuals, whose descendants remain the most prominent among today’s Christians, joined the Christian faith because they were seeking to maintain social status they had lost, and to improve on the situations they found themselves in after a bout of persecution and disenfranchisement. This makes the samurai Christians much like historical Jews.

Briefly, Jews living under early Islamic leaders also sought to advance their status, as all healthy people are wont to do. The path available to the Jews was not unlike the path available to the samurai: by plying literacy to enter into skilled trades and professional work, and by moving up the ranks of whatever governments they could because they were able, they achieved a high station in early Muslim society. With this status achieved, they were generally easily able to pay for their sons to be educated, with plenty left over for the jizya and relatively comfortable urban lifestyles.

This is a common thread tying together different elite groups: they are formed by people who want something more, and who have—or can acquire—the means to achieve it, while being or becoming distinct. These people seek out different ways of maintaining, recovering, or attaining status, and the ability to distinguish them combines with humanity’s natural penchant for homogamy so that they might maintain or grow their distinctiveness in subsequent generations. And sometimes, elite groups even do these things while losing their distinctiveness or without continued recognition that they’re part of an elite group at all.

For example, former slaveowners in the American south and former Mandarins after the rise of the communists both managed to benefit from kin who weren’t so disenfranchised. They leveraged the kindness of those who would show it to them and that helped them to get back on their feet. That wasn’t the whole story, but it helped. In succeeding generations, descendants of slaveowners were disproportionately likely to become merchants, tax collectors, and so on, whereas Mandarin descendants were disproportionately represented among educated elites. Each found paths to succeed based on what their societies made available to them, and they went down those paths.

Elite groups more generally will form through gravitating towards whatever pathways are available to achieve success. That is the story of Indians leaving Fiji as much as it’s the story of Poles fleeing Kresy or Huguenots escaping persecution in France. Fijians saw Australia open up to people with educations and they pursued education. Poles saw they couldn’t keep their possessions, so they invested in intangibles that could go with them. Huguenots learned that Germans would pay them to take up residence near factories to teach Germans to run them, so they went. But crucially, only some go.

Groups become elite not just because they strive, but because, as I mentioned a paragraph ago that they can. That means that those among them who cannot, do not. In the process of elite formation, the incapable oftentimes fall out of the elite groups that their more capable peers come to compose. This is more the case for Huguenots than for Japanese Christians, but it is nevertheless frequently the case. But I digress.1

The story of Japanese Christians as an elite group is one of transformation. It is the story of the transmutation of part of Japan’s ancient scholarly warrior class into an educated and skilled urban elite that would become accompanied by the upwardly mobile and capable that would go on to be capitalists and bureaucrats after Japan’s modernization. It’s the story behind a small but influential part of Japan’s elite, and it’s one that, if I had to estimate, we haven’t seen the end of just yet.

And I may return to this topic later to provide a more comprehensive outline, but I’m on a timer right now, so I can’t elaborate, distinguish, or clarify more here.

When I lived in Japan in the 1960s I knew a third generation Christian missionary who spoke, read and wrote Japanese better than 90% of Japanese. I was seated at a state function beside a translator who had been assigned to him by authorities unaware of his linguistic skills. After a few minutes listening to his flawless delivery she turned to me distressed, "It creeps me out to hear a gaijin talking Nihongo like that!"

Singapore is a similar case of elite Christianity.