Ozempic and Alcoholism: Does It Work?

Observational studies suggest GLP-1RAs help with alcohol abuse. Experimental evidence may soon confirm, and public health may benefit.

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than two hours to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here. If you’re looking to acquire Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, Retatrutide or other GLP-1RA drugs at an extremely low price of around $15-$40 per month, see this article.

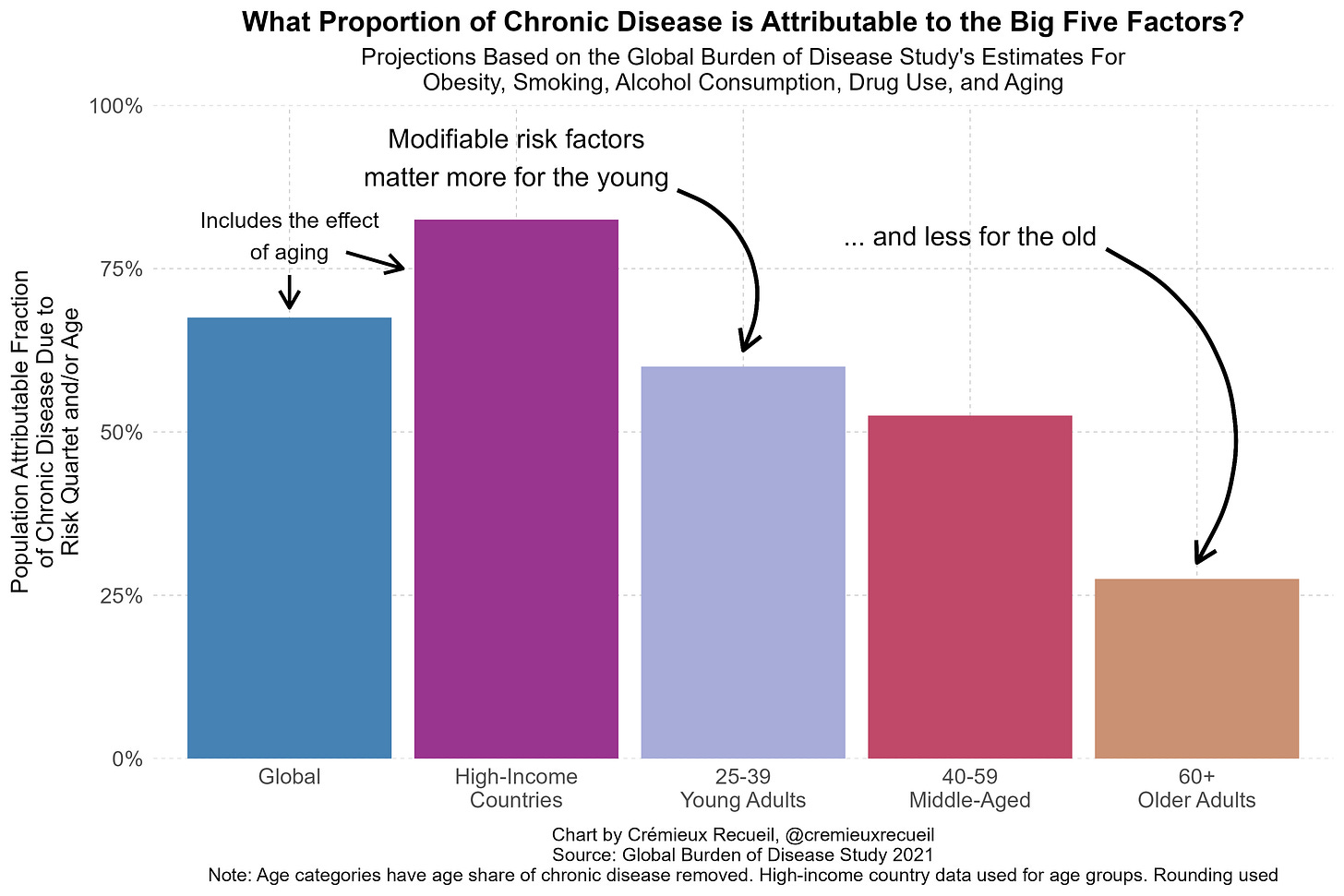

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs (GLP-1RAs) have proven to be incredibly powerful tools for weight loss. Current-generation products are strong enough to allow most Americans to achieve a healthy weight, or at least to no longer be obese. That’s a fact worth celebrating, both by the public and by health officials. With increased adoption, these drugs will result in large reductions in the burden of chronic disease in the U.S. In fact, given that some 40% of the chronic disease burden in the developed world can be attributed to obesity alone, the effects could be massive.

But fixing chronic disease won’t happen just by targeting obesity. Other factors, like illicit drug use and smoking, also play important roles in burdening the population with everything from cancer on down to cardiovascular problems. Key among these modifiable risk factors is alcohol use, which is both common and bad for you in any amount—abusive or moderate. Luckily—or miraculously—GLP-1RAs might be able to help.

Tons of Preclinical Evidence Supports GLP-1RAs For Alcohol Use and Abuse

Ample animal evidence that GLP-1RAs should help with alcohol addiction has come out since the idea was first proposed in an ADA conference presentation in 2011. GLP-1RAs impact reward feelings and signaling, they regulate alcohol-mediated responses, and may even interact beneficially with substances frequently taken alongside alcohol, like nicotine and cocaine. Researchers have replicated human-discovered genetic signals related to GLP1R in mouse models, found support for human-discovered neural signals in rodents, and noticed the more prosaically relevant finding that GLP-1RAs lead to reduced voluntary alcohol intake in rats.

The general thrust of the animal evidence on GLP-1RAs is that they’re expected to reduce alcohol intake without causing changes to other activity levels, aside from reduced eating. The research suggests GLP-1RAs don’t have this salubrious effect through inducing lethargy, and they seem to reduce cue reactivity for alcohol without affecting cue reactivity more generally. An added thing they’ve provided suggestive evidence for is that GLP-1RAs may help with the prevention of relapsing by attenuating withdrawal symptoms. More curiously, if there are benefits, they’re seemingly not obtained through mere glucose regulation.

The animal evidence is substantial and interesting, but it’s rare for that sort of evidence to translate perfectly to studies about us humans. Luckily, the preclinical human evidence is also very substantial and, I’d argue, even more interesting. I’m only going to mention some examples, because these days, these studies are coming out all the time. If I had to guess why that is, I’d peg a major factor being so many companies are trying to get GLP-1RAs indicated for alcohol abuse. I’ll return to this below.

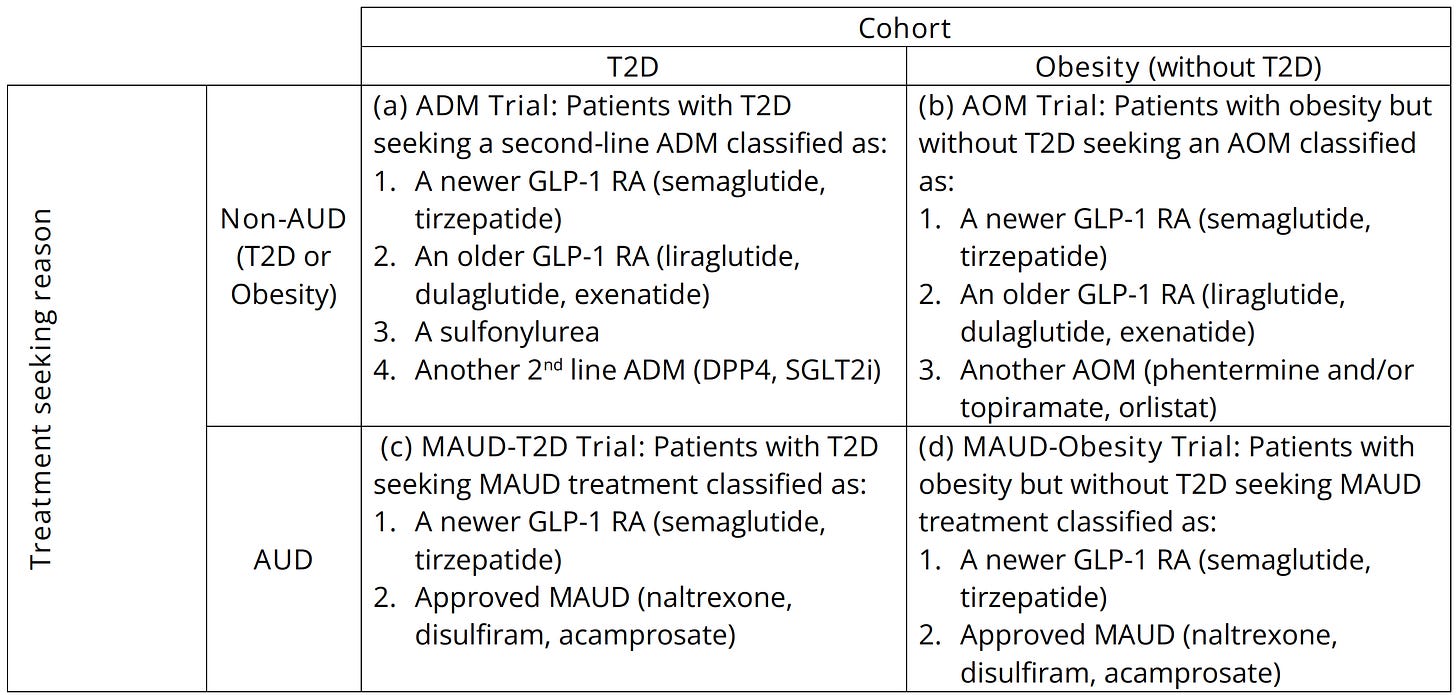

One study that I found particularly compelling involved target trial emulation for four different trials. These trials involved people with or without diabetes seeking anti-diabetes medications (ADMs) or anti-obesity medications (AOMs), and with or without the reason for seeking treatment being alcohol use disorder (AUD), as indicated by intent to pursue a medication for AUD (MAUD). The trials were classified as such:

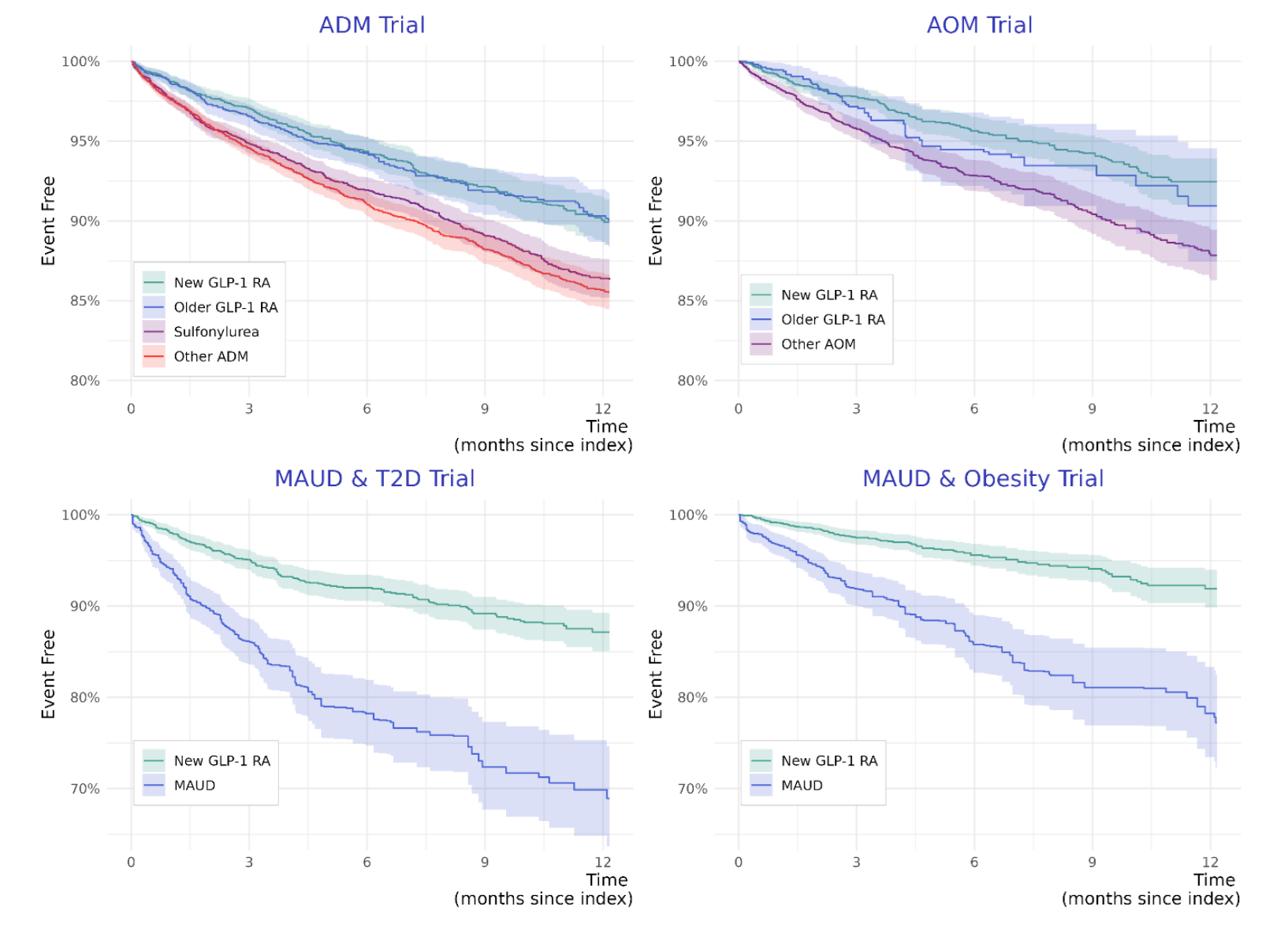

After twelve months of treatment, individuals who were on GLP-1RAs were found to be significantly and substantially less likely to have been hospitalized for alcohol-related reasons. Among those seeking MAUDs, the result was even stronger, but, a note of caution that this comparison likely leaves behind more residual confounding you’d find in the other two trials. But, I suspect those results are still basically fine, as they are substantially replicable. For example, another target trial emulation study found that GLP-1RAs lowered the risk of liver-related outcomes and death among individuals with a history of alcohol abuse, in addition to helping participants to achieve AUD remission. Those findings were themselves replicated in another retrospective cohort study, which found lower risks of death, hepatic decompensation, and developing an alcohol-related liver disease.

Most results end up being basically like this—they’re heartening and optimistic.1 I’ll briefly summarize a few of these:

Xie, Choi and Al-Aly analyzed Veterans Affairs data to compare diabetic GLP-1RA initiators to people who started using other diabetes medications and create an atlas of GLP-1RA associations with their data. GLP-1RAs helped with many outcomes and were clearly beneficial on net, but notably for this article, they were associated with reduced risks of substance use.

Wang et al. used electronic health records for obesity patients and found that semaglutide use was associated with ~53% lower risk of incident and recurrent alcohol use over a 12-month period. The same group of researchers has found that this finding holds for cannabis use and suicidal ideation. Since alcohol use is related to both cannabis use and suicides, it may be the case that these findings are linked, but more work is needed to know for sure.

Lähteenvuo et al. used data from a Swedish population register and found that AUD patients prescribed GLP-1RAs ended up with far lower risk of hospitalization than AUD patients prescribed something besides GLP-1RAs. That means that, not only were GLP-1RAs effective, they were seemingly more effective than medications intended specifically for AUD.

Qeadan, McCunn and Tingey used Cerner-provisioned electronic health records to assess the impacts of a GLP-1RA prescription on the risk of alcohol intoxication and opioid overdose. They found that GLP-1RAs were related to a greatly reduced incidence of both conditions.

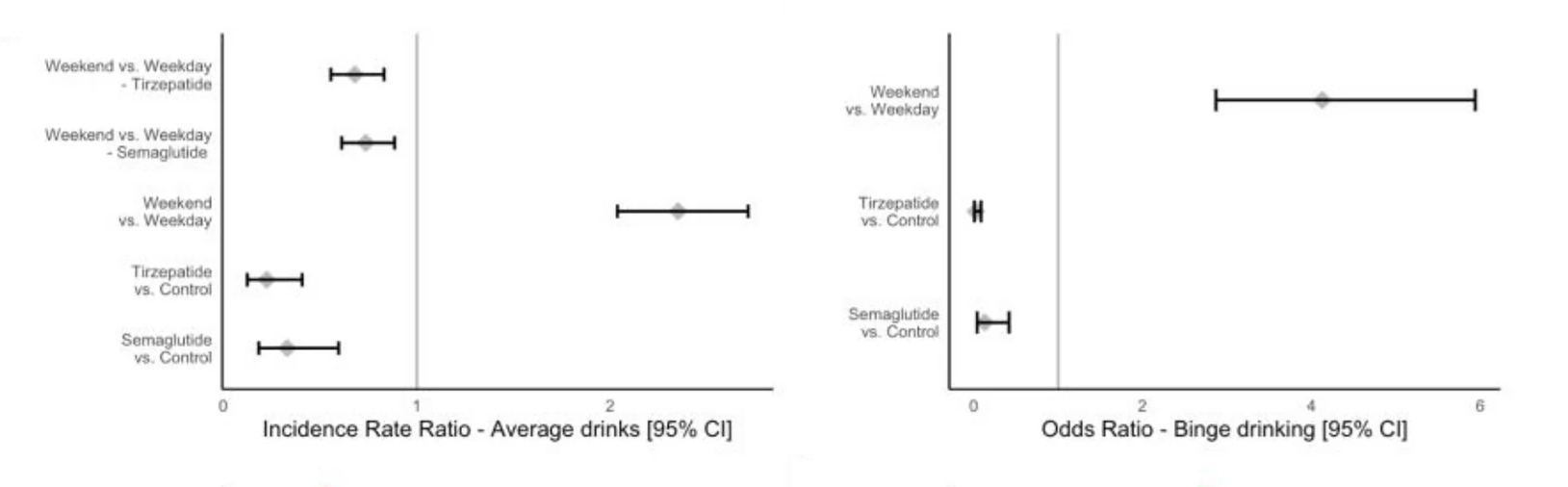

One powerful source of real-world evidence is user testimony, and thankfully, people like to testify to the benefits and side effects of GLP-1RAs online. One study leveraged thousands of posts about GLP-1RAs on Reddit and found that commenters frequently noted reduced cravings and alcohol intake, as well as negative side effects related to drinking, like increased nausea and vomiting. The same study also recruited people from social media platforms to document their alcohol usage before and after using the GLP-1RAs semaglutide or tirzepatide. Use of the drugs was associated with reduced odds of binge drinking, reduced total drinking, reduced feelings of sedating or stimulating effects, and reduced scores on an AUD questionnaire.

And There’s Some Causal Evidence

The strongest preclinical causal evidence I’m aware of was obtained with Danish register data. The study’s within-person analysis showed that GLP-1RAs led to reduced rates of alcohol-related events within the first three months of treatment. But at nine months and beyond, there were no apparent benefits. This suggests that alcohol-related benefits may be fleeting. To me, that also sounds like a point in favor of the view that if these benefits exist, they may be related to nausea. Fortunately—or maybe unfortunately in this case—nausea tends to disappear with time on treatment.2

Other causal evidence comes in the form of Mendelian Randomization (MR) studies. This method can be used to assess drug effects by leveraging genetic variation matching the way drugs work. For example, variation in the gene GLP1R plausibly mimics the effects of taking GLP-1RA drugs. So far, these studies have not been very powerful, so I’ll only mention them briefly.

One MR study found evidence of a protective effect against schizophrenia, and basically nothing else. They looked at several different mental illnesses, like ADHD, anorexia, and bipolar disorder, but none of them were meaningfully and significantly impacted by the variants the study used. I think the study wasn’t equipped to answer questions about mental health, however, as the variants it used only barely and marginally significantly related to things they should have been related to, like BMI.

Another MR study contrasted the effects of BMI-reducing variants that operate through GLP-1R agonism versus other routes. It showed promising effects via GLP-1R agonism for substance use disorders as a general category, but less promising results for other BMI-reducing variants. The effects on alcohol dependence were clinically significant, but statistically nonsignificant. When I sought to replicate this like I did for colorectal cancer, I got a significant, but small, 11% reduction in AUD.

In terms of more debatably causal evidence, researchers performed a secondary analyses of a dulaglutide trial. That provided some evidence of an effect on alcohol intake (-29%), but this wasn’t very strong by any means (p = 0.04).

Experimental Evidence!

The first RCT of GLP-1RAs for alcohol abuse came out in 2022. The drug used in the RCT was exenatide, and the results were disappointing.

127 patients seeking treatment for AUD were recruited for 26 weeks of using once-weekly Bydureon, which is just a long-lasting version of exenatide. The study used self-reported heavy drinking days as its primary outcome, and by that outcome, exenatide failed—it did not reduce the number of heavy drinking days compared to placebo. Reanalysis of a subset of the data suggested that exenatide didn’t fail, however, because it really did lead to a reduction in alcohol consumption, albeit with a delay from treatment start and with the possibility of attrition-related randomization issues.

I’m not sure how far to take this initial study’s results as a disconfirmation of the benefits of GLP-1RAs for AUD. As I noted, the study used exenatide. Exenatide generates less than half the weight loss semaglutide does, and for weight loss, semaglutide is considerably less effective than tirzepatide and retatrutide. For other outcomes, semaglutide underperforms compared to tirzepatide and retatrutide. In this study, the reduction in body weight was marginally nonsignificant (p = 0.07), so the drug was clearly not ‘powerful’ in the sense GLP-1RAs are thought to be powerful. To the extent exenatide does worse than more modern GLP-1RAs in weight loss, glucose control, and other outcomes we now expect them to modulate effectively, I expect it to do worse in AUD control, too. I don’t have any strong reason to believe this, I just take it for granted since it has turned out to be true for many outcomes when comparing liraglutide to semaglutide, semaglutide to tirzepatide, etc.

Exenatide also has peculiar pharmacokinetics when taken in the long-lasting Bydureon form. Quote: “the release profiles of Bydureon microspheres show a ‘lag phase’… after a common initial burst in the first 2 days due to the loosely bound exenatide on the surface, the drug is not released until 2 weeks later, and it takes up to 7 weeks for complete release.” This is unlike what we see with modern long-lasting GLP-1RAs which have extended half-lives due to structural modifications like Fc and albumin fusion, peptide lipidation, and various sequence changes. The unusual microsphere-based delivery lends itself to “poor pharmacokinetics and efficacy”.

New Experimental Evidence!

Not to worry: there’s a new trial, and its results are interesting!

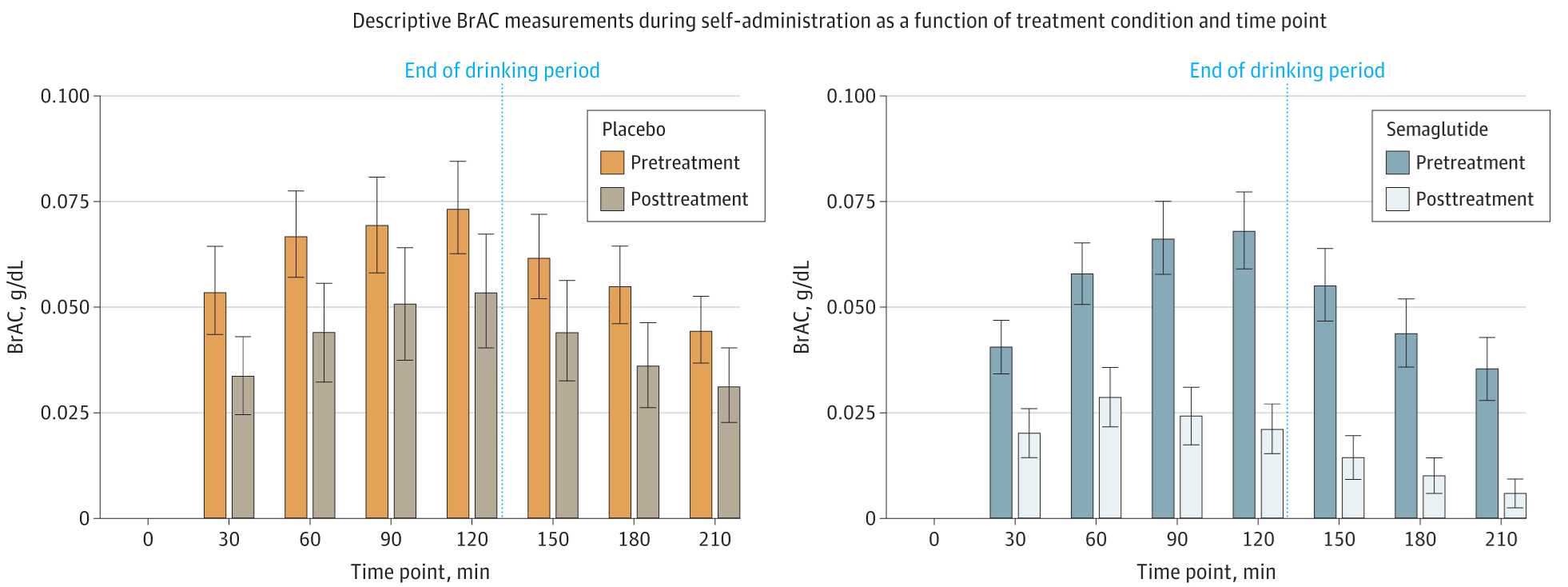

This trial saw forty-eight alcoholic participants who weren’t seeking treatment split between either a once-weekly semaglutide injection or a placebo injection. Before randomization, participants were sat down in a laboratory setting with their preferred type of alcoholic beverage, and asked to delay drinking said beverage for up to 50 minutes for a small cash reward, seemingly of around $10. After 50 minutes, participants were then told to consume as much alcohol as they wanted for two hours. Their breath alcohol concentrations (BrAC) were then measured and tracked over time.

This experimental setup is not unusual; many studies have used it, and it appears to be a valid setup for assessing alcohol intake, pharmacotherapy effects, and so on. The problem with the setup in this study has to do with attrition. In the pre-treatment laboratory setting, two participants from the eventual placebo and eventual treatment groups elected not to take part in consuming any alcohol. This isn’t inferentially problematic, as it happened prior to randomization, but what is problematic is that, in a follow-up after nine weeks where this procedure was repeated, seven placebo and nine semaglutide group participants elected not to consume alcohol. How selective is this? We don’t know! There aren’t even enough participants to credibly figure out if this is selective with respect to treatment assignment, and it might even be the case that it should be selective with respect to treatment assignment. All of this is to say, the study’s focal laboratory-based result might have been affected by randomization coming undone. Or this might be what’s expected if the treatment works. Not partaking in alcohol is a goal of giving these substances, so the meaning of this result is really unclear.

I kind of doubt this is a big issue, but I still felt it needed to be mentioned. In any case, here’s the result:

Notice what’s going on here. Prior to randomization, both groups had a similarly-shaped and similarly-sized increase in BrAC, with declines after alcohol administration ended. That’s pretty much exactly what you’d expect from this design, so nothing problematic there. But after a bit over two months of semaglutide or placebo treatment, the shapes of the distributions diverged. For the placebo group, the shape remained the same, but the amount of drinking declined. For the treatment group, the shape of the distribution changed radically, with a peak half-way through alcohol administration rather than near the end of the administration period. Moreover, the magnitude of intake fell considerably.3

In a laboratory setting, GLP-1RA users really showed that they had lower alcohol intake! The missingness of the data notwithstanding, this is a reassuring and hopeful result. It’s also complimented by some other results that I think are worth briefly mentioning. The first of these is that the drugs definitely worked as they normally do. We know this because the sample taking semaglutide lost a lot of weight, where the placebo group did not. Secondly, the treatment group reported less alcohol craving, but only after about four weeks in; before then, differences were mostly directionally consistent, but statistically tenuous. Finally, people’s self-reported alcohol intake did appear to decline more in the treatment group than in the placebo group.

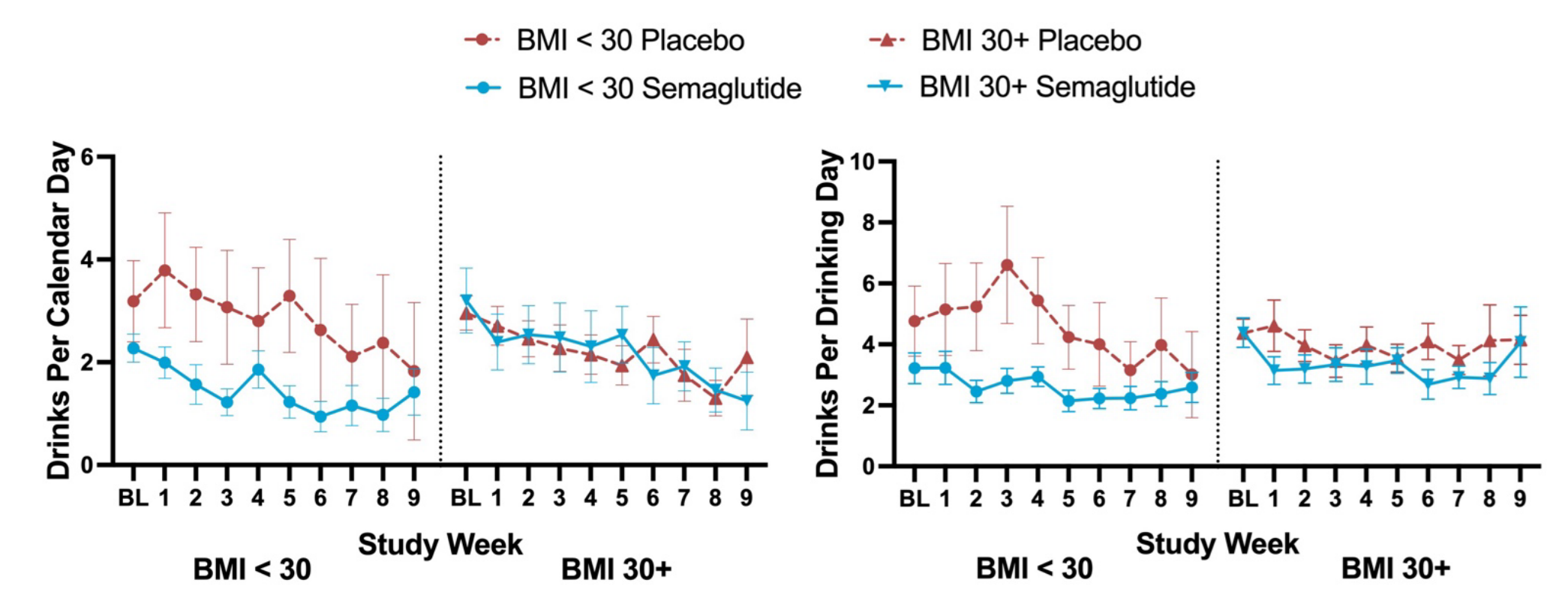

These last two outcomes appear to support the laboratory results, but they need to be caveated. Firstly, the appearance of the craving benefit after a month could be driven by attrition. If the data was made available, we could check this empirically. Secondly, and more alarmingly, the apparent benefits for self-reported alcohol intake were plausibly just due to a randomization failure from the start. In the supplementary material, we’re greeted to a few graphs that show that differences in intake over time were BMI-related and present from the start of the experiment:

What this experiment shows is, therefore, ambiguous. While the authors might be correct that AUD can be treated with GLP-1RAs, they ultimately only provided a small amount of evidence in favor of their position.

Newer Experimental Evidence!

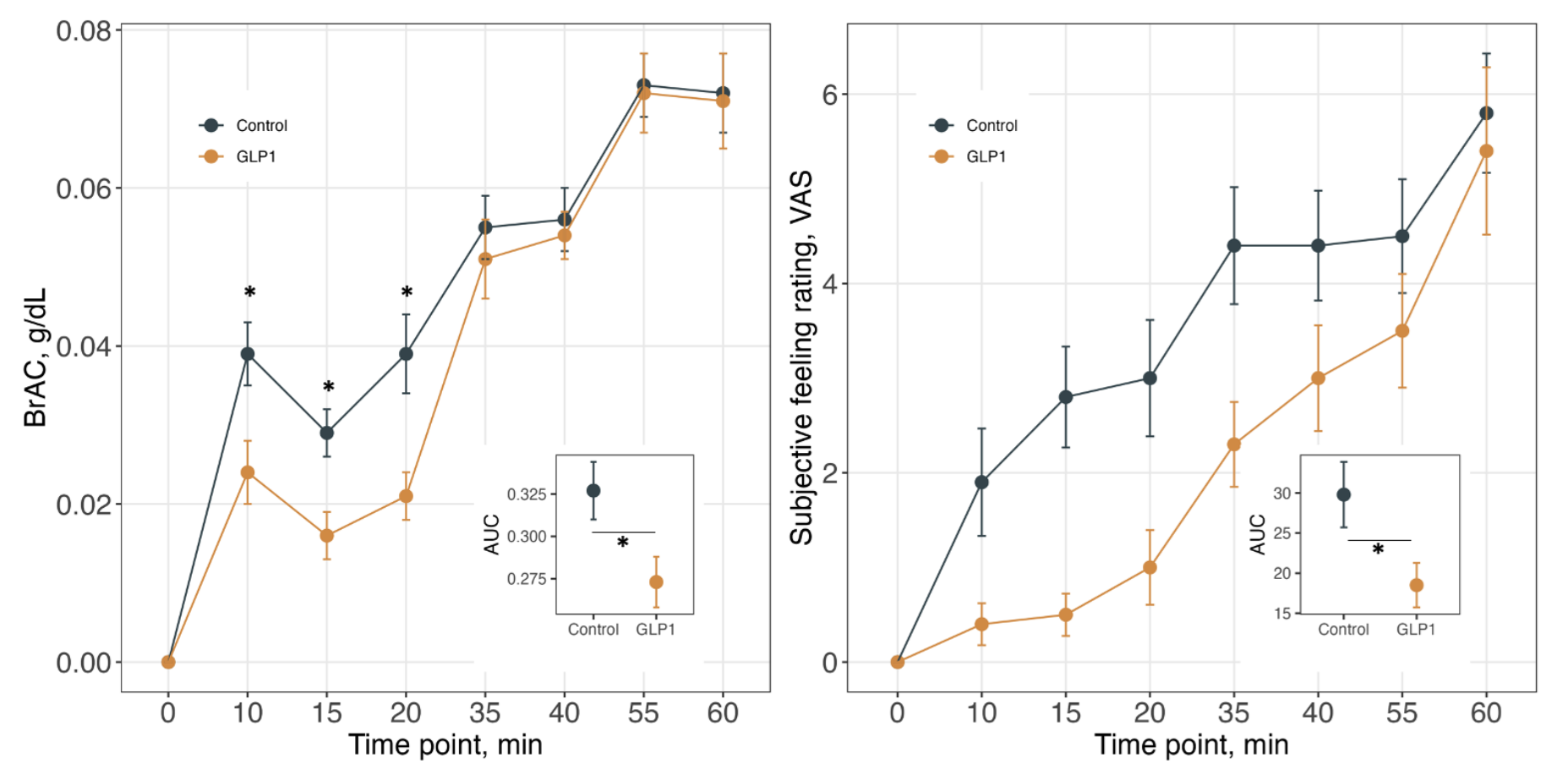

After that experiment’s results came out in February, another experiment’s results were published in April. This experiment is not an RCT, but it is still worth remarking on. The experiment involved the recruitment of a small obese treatment group who were people taking a maintenance dose of GLP-1RAs and an obese control group whose members were not taking GLP-1RAs, and then putting them in a lab with alcohol and recording people’s objective and subjective feelings of intoxication after consumption.

The results of this lab experiment lined up with animal experiments. In terms of BrAC, GLP-1RA users had a lagged increased, possibly due to gastroparesis. This lagged increased was followed by a lagged increase in subjective feelings of intoxication. This could be great for helping with AUD, since it suggests GLP-1RAs might stall the onset of the mood benefits AUD sufferers gain from alcohol. If that happens, they might be more aversive towards and less desiring of alcohol. But, let’s be clear: this is just a potential mechanism. Whether this translates to actual benefits treating AUD remains to be seen, but it is still very cool!

The Near-Future of GLP-1RAs For Alcohol Abuse

My read of the evidence on GLP-1RAs for alcohol abuse is that there’s good reason to think they’ll be effective for a sizable subset of the population, but there’s reason to doubt they’ll have a miraculous effect. The preclinical evidence is a home-run, the anecdotal benefits are extensive and likely warrant off-label usage regardless of what trials show us about AUD, the existing causal preclinical evidence is suggestive, and the clinical evidence is poor.

I give GLP-1RAs for alcohol abuse a decently high probability of success (~60%).

There are, at this very moment, more than a dozen ongoing alcohol-related GLP-1RA trials. There are trials that use mazdutide (NCT06817356), cagrilintide (NCT06409130), frequently tirzepatide (e.g., NCT06727331, NCT06994338, NCT06939088), and most often semaglutide (e.g., NCT05895643, NCT06546384, NCT05892432, and many more). All the trials I’m aware of are running through 2028 at the latest. There are so many of these trials, and they are altogether so large, that they will establish definitively whether GLP-1RAs are effective for alcohol abuse, we just have to give it time.

Despite the reasonably high probability of success at treating AUD and the large amount of industry support for GLP-1RAs for alcohol-related indications, I give the probability of approval in the U.S. lower odds than the probability that they work for this condition overall (~35%). My reasoning is simple: I believe that the current FDA is more hesitant to approve GLP-1RAs for adventurous indications.4

The Biden FDA approved GLP-1RAs for several indications beyond obesity and diabetes management. They issued approvals to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke (March 2024), for sleep apnea (December 2024), and holdovers approved it for chronic kidney disease on January 28, 2025. To be fair, the FDA under Trump I approved liraglutide (August 2017), semaglutide (January 2020), and dulaglutide (February 2020) for cardiovascular risk reduction among diabetics, but the FDA under Trump II is radically different.

The ability to get approvals like the ones issued with the Trump I and Biden administrations is not as certain because the staff of the FDA now are much more conservative about approvals. Or at least, many industry leaders believe they are, and that’s more than sufficient to warrant terminating trials. The conservative attitude towards approvals has to do with concepts like avoiding medical reversal, but also with the choice of more conservative staff for reviews and approval decisions (e.g., Vinay Prasad), perceived ideological opposition to the ‘overprescription’ (so to speak) of and population dependence on drugs like Ozempic, as well as the perception of trial lawyering (see: talc, synthetic dyes, and the leaked food additive reconsideration list). That last point is actually key, because it means that manufacturers will have to take ignorable safety signals much more seriously,5 possibly adding considerable R&D and compliance costs and putting them in a position to reconsider more of the things that they want to do.

Whether these beliefs have merit or not, they are still driving decision-making processes at different pharmaceutical manufacturers. These considerations are likely the most serious factors that will determine what happens with GLP-1RAs for alcohol use and abuse, and that’s not good! This means that, even if it turns out GLP-1RAs are successful drug targets for this indication, they might not make it to consumers, at least on-label.

But let’s hope everything works out, and let’s hope the effects look like they do in the the preclinical human studies. If that’s the case, then we might be able to use GLP-1RAs to, say, halve the fairly substantial chronic disease contribution of alcohol consumption. Add this to the part of chronic disease attributable to obesity—which these drugs already treat—and they’ll probably at least halve chronic disease burdens in developed countries like the United States. That’s a lot to look forward to.

November 19 2025 Update: A New Review!

A new systematic review on this topic just came out. If you’ve read the article above, you basically already know what’s in this review, in addition to more qualifications on the results and reasons to feel like there’s hype to be wary of.

As far as I’ve seen, the studies that say otherwise are studies in which the comparison groups for GLP-1RA users are faulty. For example, this study compared GLP-1RA users and non-users and found that GLP-1RA users were at a greater risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior. The issue is that GLP-1RA users are not random, and the propensity-score matching used in this study didn’t do enough to overcome this issue. If they had matched, say, samples of diabetics prescribed a GLP-1RA or a non-GLP-1RA, or people prescribed a GLP-1RA for obesity versus another drug for obesity, then they likely would’ve produced a result more in line with the rest of the literature, which is to say, it likely would’ve been positive towards GLP-1RAs.

Side effects can also be reduced in severity and prevalence with slower titration.

This result is based on BrAC measurements, so one complaint might be that gastroparesis drives it. That would lead to a detectable, delayed rise that we don’t see, so that doesn’t explain this.

And without approvals in America, many companies just give up on seeking approval. The American market is worth that much.

This is a very unfortunate fact because of how common false or misleading safety signals are.

Consider NAION, which a clearly unrepresentative, small, and absurd study suggested was a genuine thing for GLP-1RA users to fear. If the study was correct about the scale of the safety issue it identified with NAION, then the drugs would need to be pulled immediately because millions of Americans would already have gone blind. There’s no mass blindness epidemic due to GLP-1RAs, so clearly there’s something wrong with the study. The best follow-ups failed to support it any risk elevation, and other work has suggested that NAION and problems like it might be specific to certain identifiable subgroups.

Manufacturers can end up having to warn patients about this side effect, even if it’s not real, and this can happen for tons of different side effects. For example, pancreatitis does not appear to actually be a side effect of using GLP-1RAs, but some studies with poor comparison groups suggested that it is, and some people have ascribed their pancreatitis to taking the drugs, and some providers have supported these concerns as well. Accordingly, manufacturers have to warn about pancreatitis risk. More pressingly, they have to worry about their drugs being pulled if the safety signals are serious enough. Unnecessary withdrawal has happened to drugs like phenylpropanolamine, so it is a real concern.

One area I’ve had my eye on for false safety signals is mental health. Several drugs have been pulled for links to suicidal behavior, disinhibition, depression, and so on. Generally, GLP-1RAs are found to be related to a lower risk of depression, lower risk for a variety of mental health problems, and at the very least, no worsening in mental health. As noted earlier, there are also indications of benefits for other psychiatric conditions and suicide risk. Moreover, we have mechanistic evidence to suggest that neural insulin resistance is linked to depression and anhedonia, and we know that GLP-1RAs help with insulin resistance and preclinical evidence suggests they should help with it in the brain as well. There’s suggestive evidence that people tend to be more active after time on GLP-1RAs, but, despite all of that, GLP-1RAs could still plausibly lead to anhedonia and other depressive issues via pathways like those implicated in its effects on reward behavior. Even if such a symptom only manifests in a very small subset of users, that can be more than enough to limit the drugs or to outright ban them. Similar things have happened before.

I doubt a ban will happen because the drugs are so commonly used, the safety profile is so well understood, and there’s no real replacement, but the odds of a ban feel higher than in previous administrations because of the known ideological shift that came with the introduction of the MAHA faction to the HHS. As noted above, whether that perception is accurate or not remains to be seen, but its truth is ultimately immaterial because the added worry among manufacturers is now going to be there regardless.

I would encourage skepticism of the retrospective studies that include GLP-1s other than semaglutide and tirzepatide. The strength of craving reduction in these vs previous generation GLP-1s is big, so broadly lumping everything together as "GLP-1RAs" is very diluting, but several patient health record studies have done so. Our organization CASPR.org works on this issue and is creating a spinout to seek FDA approval for AUD.

Anecdotally my experience with zepbound was that it had a very strong inhibitory effect on alcohol consumption for the first few months, but that effect waned over time even as the effect on appetite (and weight loss) continued.