The Demise of the Flynn Effect

Massive changes in IQ scores over time are much less meaningful than people think

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

Are we getting smarter? Are we getting dumber? Headlines and anecdotes are bisexual about these questions. The mainstream view is that we’ve been getting smarter and dumber at different times:

Prior to the 1990s, the 2000s, or the 2010s—depending on who you ask—people were getting smarter all the time: the Flynn Effect, as commonly1 understood.

After the 1990s, the 2000s, or the 2010s, people have been getting dumber and dumber, the kids can’t sit down in class and don’t want to work, and colleges are full of dimwits who can’t pass muster in weeders: the “Reverse Flynn Effect”2 so many have now heard about.

There’s something to this mainstream view. Take, for example, the mean IQs over time in this Norwegian conscript data for the years 1957 to 2008:

Adults closer to today are much smarter than they used to be, but not quite as smart as they were back in the early 1990s. Right? Not quite. Notice how it’s not every test that’s affected:

To get an idea of what each of these tasks represents, look at these example questions:

Now that you understand what the different tests are getting at, ask yourself: Why might performance on figural matrices tasks have increased so much over time while performance in mathematics stagnated? While we’re at it, why did people only get somewhat better at word similarity tasks? If people were just getting smarter, then all of these scores should have gone up, and to degrees predictable from each tests’ relationship with the general factor of intelligence, g (or “GMA” for general mental ability), so that can’t be it.

This article is not going to give you a satisfying answer to those questions, it’s just going to tell you the psychometric rather than the substantive answers. The psychometric answer to each of those questions is the same, and it’s one word: bias.

One of the most important studies on the Flynn effect was just published in the latest issue of the journal Intelligence. This study is so important because it has a few qualities every other study in the literature lacks. It’s not unique in having a large sample or covering a large period of time; the uniqueness of this study comes from the fact that the same test was given to generations of successive population-representative birth cohorts coupled with the fact that the authors had the perspective to choose to analyze the data in a psychometrically appropriate way.

If you’re unfamiliar with the psychometric methods I’m about to describe, go read my explainer article on this topic, here:

What these authors found was that the Flynn effect is a phenomenon necessarily undergirded by psychometric bias, meaning that what the tests measure changed over time. For example, how different cohorts understood the tests was different, as indicated by the fact that the relationships of the tests with g were not constant over the years:

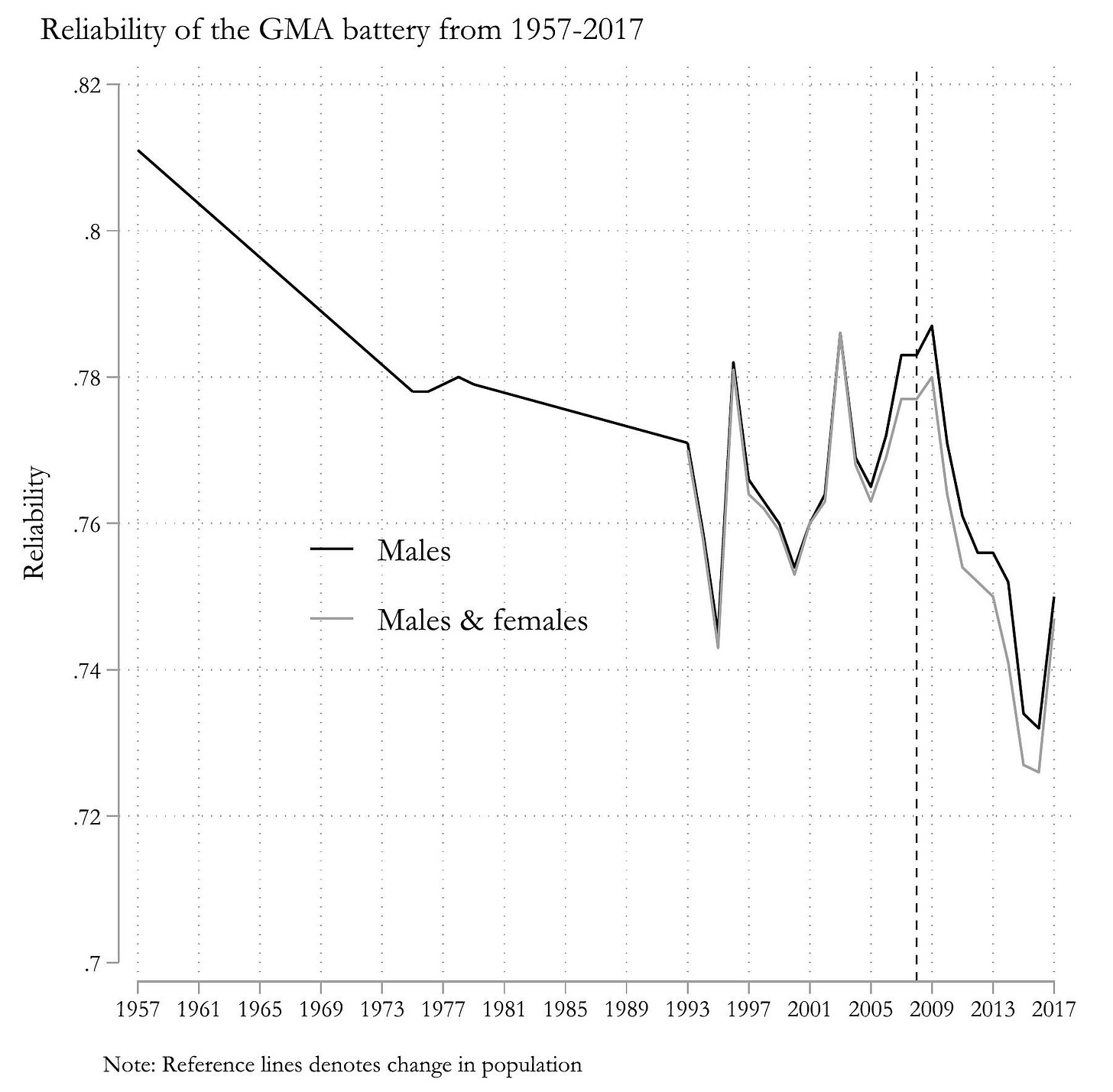

The levels of test-takers’ scores were also not comparable over the years. Every time the authors of this analysis tried to restrain the regression intercepts on g to be equal across cohorts, the model became unacceptably poorly-fitting. Beyond that, there were very likely to be different influences on test scores over time, as indicated by trends in test reliability, so it would have been impossible to find strict factorial invariance in this data.

The authors provided a description of these results in laity-friendly terms:

Overall, the Flynn effect, and the Flynn reversal argued for with these data reflect an increase in the test-specific ability of figure matrices reasoning, not the variance explained by the GMA factor, and the Flynn reversal reflects reductions in test specific abilities in the word similarities and the math tests.

Or, even more to the point:

Observed increases and subsequent decreases in intelligence scores do not reflect changes in latent intelligence.

Against Lay Thinking About Empirical Topics

Tons of earlier studies have shown that the Flynn Effect is essentially a problem of test scores becoming incomparable over time, rather than population intelligence changing. After accounting for incomparability, the Flynn Effect and its reversal both tend to disappear, leaving behind no changes in intelligence and meager score changes after they’re fully corrected for changes in how people understand the tests.

Why the understanding of tests changes is an interesting topic that’s worthy of investigation in its own right,3 but it is boring and academic, and that’s why it won’t receive the attention it should have. But, that’s also how the Flynn Effect ought to be: boring and academic, precisely because people are prone to abusing findings that become too exciting.

People want to think that population intelligence shifts up and down, and that people become smarter and dumber all the time,4 but the reality is that the population practically hasn’t changed any more than you’d predict from shifts in demographics. People want explanations, and they often think they have them, even though most common explanations—education, technology exposure, family size, hybrid vigor, blood lead levels, genomic imprinting, pathogen levels, nutrition, IQ variability, social multipliers, etc.—cannot be compatible with the boring and academic psychometric reality of the results.

I take for granted that the public wants to explain things in real terms. They do not think about methodology when it comes to any topic, and the Flynn Effect is essentially a methodological phenomenon. Because of that fact, the Flynn Effect as understood by the lay public is dead and discourse on it should stop. Simply put, laymen are not equipped to and do not need to understand it.

And incorrectly.

Not the Anti-Flynn Effect or “Woodley Effect”, which refers to increasing specific skills and declines in general intelligence.

Some people believe that the interpretation of test scores has changed because people play more games now, and those games are like the content traditionally on IQ tests. This makes the most sense for tests like the figural matrices, which are commonly employed in videogame, children’s books, and so on. But this is all neither here nor there.

People also want answers to questions like “Why do children seem to be struggling more today in schools?” They usually fail to support the thing they’re wondering about before jumping to explaining it in terms of, say, a Reverse Flynn Effect, but if they were circumspect, they would verify problems exist before attempting to explain them.

Thanks for this post. I always found the Flynn Effect very suspicious, but didn’t have a good place to hang my skepticism.

OTOH, as someone who was a Norwegian conscript in 1994, it’s too early to tell to whether vanity will win out over confirmation bias in how this gets filed in my long-term memory. 😉

Unique opportunity to name an effect after what is discussed in the post 😄