The Value of Foreign Diplomas

Is that immigrant high-skilled or do they just have a fancy degree?

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

You have two practically identical résumés sitting in front of you: same level of education, same limited experience because they’re young, same claimed technical expertise, and so on. But, there’s one key difference: Applicant A went to Harvard, and Applicant B earned their degree from DeVry University. You want to hire the best employee, so which one are you more likely to call back?

The honest answer from almost everyone will be Applicant A, and there’s good reason to make that choice: People who go to Harvard are, all else equal, likely to be more capable than people who go to lesser-ranked universities. The screening process to get into Harvard is more intense than elsewhere, so the wise employer picks up the phone and knows exactly what to do in this situation.

But somehow people seem to forget this when it comes to other comparisons. One such comparison is between America’s natives and its immigrants. Let’s look at that.

The OECD cognitively tests the adults of various nations as part of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies or PIAAC. In the latest PIAAC iteration, participants’ literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving skills were tested. The literacy questions were like this:

The questions were entirely not hard, but they’re hard enough that they manage to discriminate different ability levels reasonably well. The numeracy questions were similarly easy. For example, here’s the “Render Mix” question:

The adaptive problem solving section has less obvious content. Defined as “the capacity to achieve one’s goals in a dynamic situation, in which a method for solution is not immediately available”, adaptive problem solving is said to require participants to engage “metacognitive processes” to define and address different problems. As an example, here is the “Best Route” question:

Again, not hard.1 But if you sum up people’s correct (1) and wrong (0) answers, you get a nice bell curve of scores without much range restriction in most participant countries.2 For my purposes, I’ll be using the data from just one country though: the United States of America.

In the U.S., the tests are administered entirely in English, and in the latest wave, they’re administered in a computerized format. Given the language of the test and the nature of the comparison we’re about to embark on, an obvious question is Are the tests biased by language? Immigrants might not have enough English language experience to fully perform on the tests for reasons of experience alone. But this is no big deal for a few reasons. Substantively, English language skills matter, so deficiencies in English signal assimilation issues. Also, we can compare immigrants who’ve been in the U.S. longer to those who are more recent arrivals. But more directly, we can just see if the tests display measurement invariance. If they do, there’s no language issue and scores are directly comparable.

Since we have item-level data I used the method in this paper to compute a measure of aggregate bias (ETSSD) for items at the subscale level with at least 80% pre-imputation3 coverage in three groups: Natives with degrees, immigrants with degrees from the U.S., and immigrants with degrees from outside the U.S. I did the bias comparison between natives and immigrants as a whole because the sample size for immigrants was only a couple hundred. The result of this analysis isn’t very meaningful: Literacy was biased 0.01 d in favor of natives, numeracy was biased 0.05 d in favor of immigrants, and adaptive problem solving was biased 0.06 d in favor of natives. This might be meaningful in some other context, but the scale of the native-immigrant gaps in performance was much larger, as you’ll see.

In order to make scores meaningful, I’ve put the scores for natives with any degree, immigrants with any degree from the U.S., and immigrants with any degree from outside the U.S. into percentile terms, where the 50th percentile is defined as the median for all natives irrespective of education.

U.S.-educated immigrants do marginally better than natives as a whole, but considerably worse than natives who have any sort of degree. But more shockingly, natives without degrees who only have some college experience also manage to outperform both types of immigrant, with literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving percentile scores of 54, 53, and 59. Native college dropouts only lag on numeracy, and not significantly.

In standardized terms, U.S. natives with degrees respectively outperform immigrants with U.S. and foreign degrees by 0.30 and 0.62 Hedge’s g in literacy, 0.19 and 0.35 g in numeracy, and 0.43 and 0.53 g in adaptive problem solving. Accounting for the bias mentioned above has practically no effect on this picture.

I’m not the first person to notice this. Just a few years ago, Jason Richwine analyzed an earlier wave of PIAAC data and he observed the same pattern. I’m effectively replicating this:

Unfortunately, then and now, the amount of data isn’t enough to really pick apart every little category of immigrant. We can split the data up, but the results beyond the big picture quickly become extremely statistically uncertain. If we want more certain answers about exactly how skilled different immigrant national, occupational, and educational groups are, the easiest way would be for the U.S. to restart the New Immigrant Survey.4

We do have a decent amount of power to break apart the native group. We know, for example, that natives with bachelor’s degrees alone score better than immigrants with U.S. degrees of any sort, those with bachelor’s degrees, and even those with advanced degrees. Natives with advanced degrees score even more highly. We also know more heavily-replicated facts, like that White natives score about 1 g above Black natives, and that they score higher at the same levels of education, that male and female natives score similarly highly, and so on. But let’s focus back on immigrants by talking about potential immigrants.

What About Offshoring?

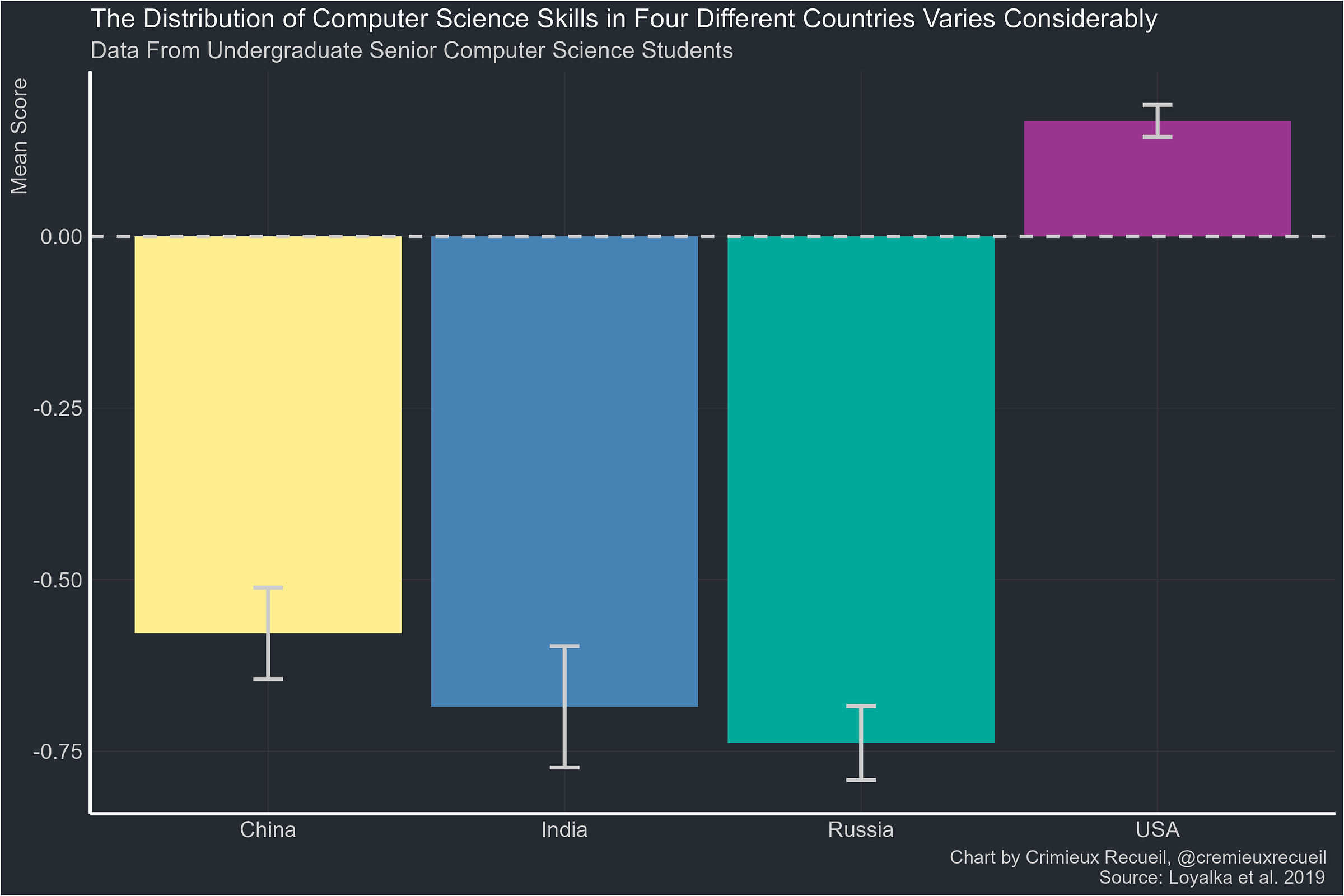

Foreigners are often sought after for the educational credentials they hold in different countries—offshoring services! This is common for a few fields, but a notably high-skilled one is computer science. A revealing 2019 study by Loyalka et al. showed that the educations of foreign computer science students aren’t comparable to U.S. educations.5

Loyalka et al. used an expertly translated and psychometrically vetted test of computer science skills and gave it out to thousands of final-year computer science undergraduates across China, India, Russia, and the U.S. Americans far and away outperformed the seniors in ostensibly similar programs in any of the comparison countries:

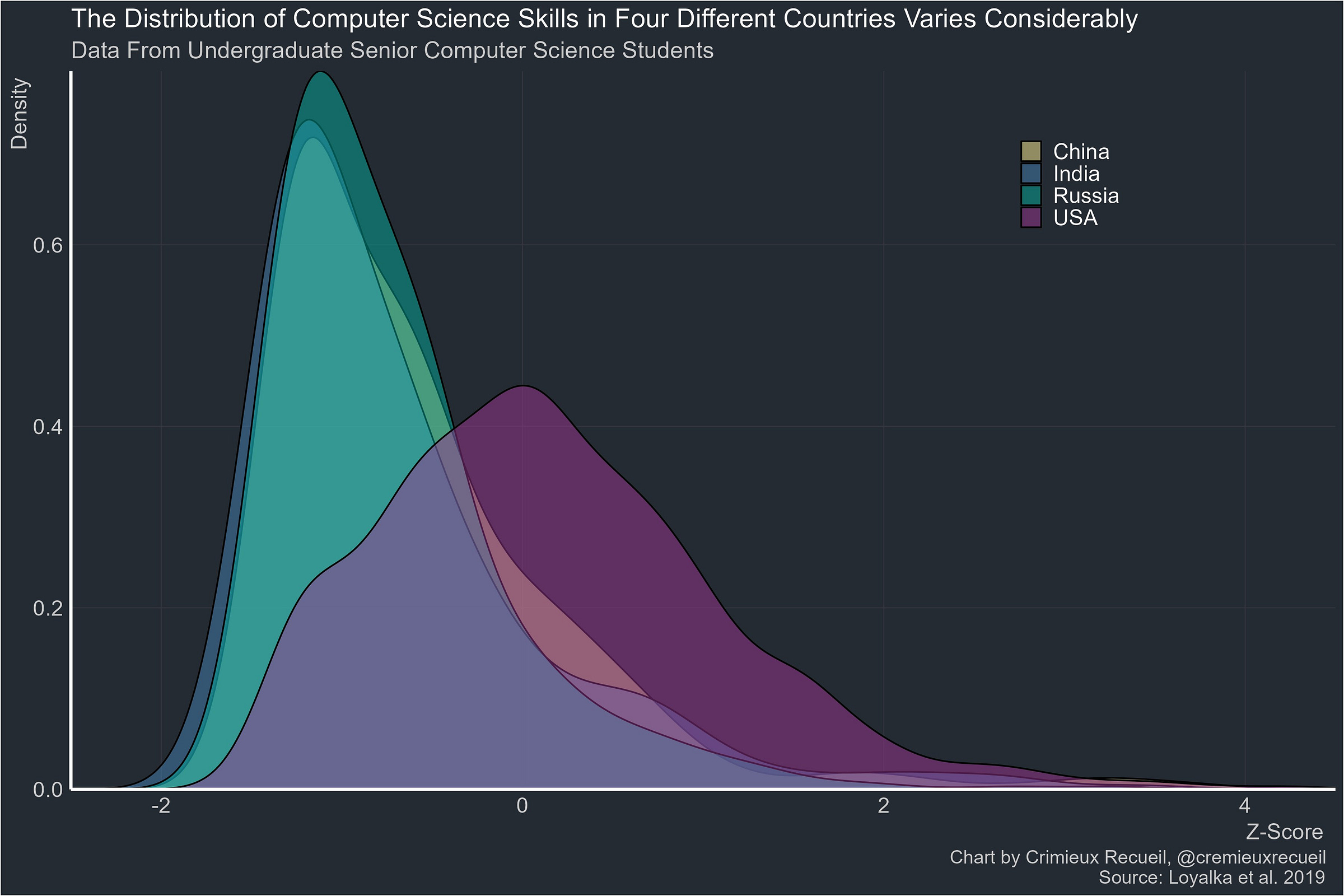

This skill delta in favor of the U.S. couldn’t be attributed to a high number of international students—if anything, America’s non-international students performed somewhat better—nor could it be attributed to an overrepresentation of elite school attendees in the American sample.6 At the end of the day, American students just tended to be more skilled, and there’s not even a saving grace in the form of higher variance in China, India, and Russia.7 In fact, the opposite is true:

But, though American natives are quite skilled relative to both immigrants and their foreign peers who their work might be outsourced to, there’s still another group that needs to be discussed: people who choose to pursue skill development because they want to go to America!

What About Brain Gain?

Some economists have recently begun to argue that brain drain—where smart or skilled people leave for another country—isn’t a problem. This argument is a matter of degree. Plenty of people now say it doesn’t exist full-stop and others argue there are offsets, so its harms have to be considerably qualified. The reason brain drain effects need to be qualified is that when skill-based ways to migrate open up, people in sending countries start training, getting educated, and working on their skills so they can become eligible to move. Those countries thus experience “brain gain”.

As an example, the U.S. once opened up more visa slots for nurses and people in the Philippines started to move into nursing to take advantage of these visas. Then when the slots closed, nursing program enrollment declined:

The argument is that the brain drain possibility (and reality) led to people training more, increasing skills in aggregate—that human capital increased in the sending country a result of the possibility of brain drain! But it’s not clear that’s what happened. I’m not sure of any instance where brain drain actually leads to “brain gain” in the sense of actually counteracting brain drain effects on a population’s average level of ability, even if it leads to more people having training. The proof is in the pass rates: we can see that the people who decided to go into nursing passed less over time.8 Given equal variances, going from 60% passing to 40% passing is like losing half a standard deviation in ability!

That the new nurses aren’t as smart as the old nurses is probably a tautological finding because the number of people in nursing greatly increased over time.9 Similar things have happened elsewhere. For example, I’ve noted before that when Denmark increased the number of PhD program slots, the average ability of students fell. Likewise, increased college participation seems to explain why officers in the U.S. Marines Corps are less competent today than they used to be. The increase in college participation rates also explains the more general decline in the ability level of college students.

Beyond “brain gain” not having been shown to result in a more intelligent and capable population, but rather just one that’s trained differently, another issue with claims of brain gain is that it can have broad effects. Consider the Philippines’ example, where nursing seemed to take a bite out of the growth of other majors. Who’s to say the skills prioritized to emigrate are those the country needs? Who’s to say they’re the most cognitively demanding or enhancing? This style of brain gain can also disrupt training internationally. A recent example of this comes from the H-1B visa, which seemingly promotes people in India majoring in computer science to leverage the visa—brain gain—while reducing the odds U.S. natives major in computer science—brain… what? loss? Non-specialization? I’m unsure! But one thing is clear: the issue of brain drain hasn’t been eliminated.

What About Reform?

One of the common defenses of the diversity lottery—where the U.S. randomly hands out visas to 50,000 applicants from countries with low immigrant numbers in the U.S.—is that the winners often have a bachelor’s degrees, so they must therefore be elite. After all, they’re ‘educated.’ But degrees are not equal and we all recognize this fact when we compare a degree from Harvard to one from DeVry, but seemingly few people recognize it when they’re talking about the degrees held by natives versus the degrees held by foreigners, aliens, and immigrants.

This is a problem. There’s no direct immigrant screening by ability, but degrees do help with getting in, and degrees, as we’ve seen, are not all equivalent. An obvious solution to the ‘degree is not a degree’ problem in immigration is to test immigrants and to only let high-ability immigrants through. This has an added benefit in that degrees can be deprioritized in general and bias due to degrees being harder to earn in different countries can be eliminated. This means more Ramanujans and fewer fake Nigerian doctors. The effect of this would be, in some ways, analogous to the effect of using standardized tests for university entry in the U.S. in that the tests would remove bias from the system and help to ensure a better output.

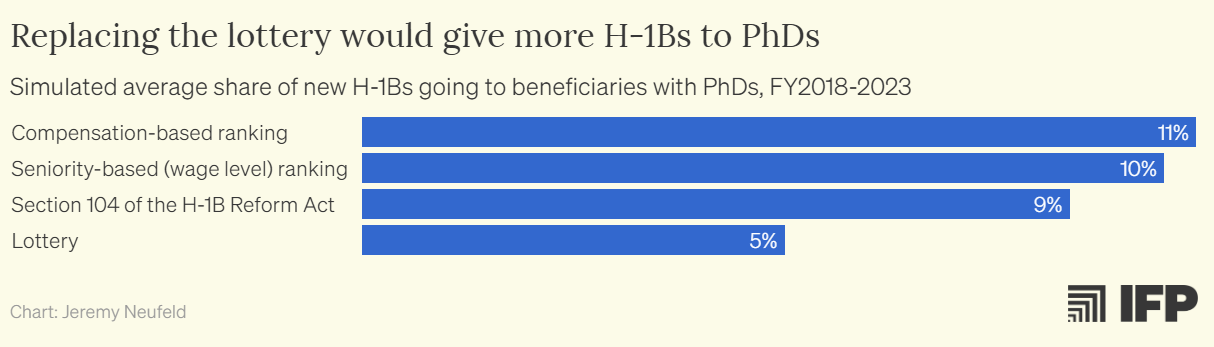

Testing is easy, often already done by institutions like India’s IITs (JEE) or College Board (SAT), and it seems like a no-brainer for certain visas, but definitely not all of them. For people coming to the U.S. as workers, a simple way to ensure a higher quality of immigrant with better effects for American natives is to change visas like the H-1B from being based on a lottery to being based on employee seniority or, better, compensation.

This has been proposed by the Institute for Progress (IFP) in a report that estimated that seniority-based ranking would increase the economic value of the existing H-1B crop by 48% over ten years, whereas compensation-based ranking would increase it by 88% over the same timeframe. And note, that boost is without expanding the cap by a single person. All it does it make the group that comes over more deserving by virtue of being more highly skilled and beneficial to Americans.

The IFP also estimated that reallocating H-1Bs based on educational credentials and in favor of graduates from American universities as in Section 104 of the H-1B Reform Act would boost the value of the program by a smaller amount, by just 35%. Also, reform based on that act’s explicit focus on education would lead to a less PhD-filled crop of H-1B earners compared to both seniority and compensation-based rankings. Clearly the better option is to focus on a more direct measure of skill, to do compensation-based ranking. And if the goal is to maximally enrich the American public, the annual cap should also be lifted considerably, but consider that a discussion for another time.

Recap

One of the most important things to note from this article is that Americans are not dumb. If anything, Americans are some of the smartest people in the world (I think that should be better-recognized). Degree-holding immigrants don’t tend to outmatch degree-holding natives, and Americans have plenty of room to specialize and train in currently immigrant-dominated fields.

People overestimate the smarts of immigrants coming to the U.S. I recently ran some polls on this topic on X/Twitter, and people tended to rank immigrants with U.S. degrees above American natives, who they ranked above immigrants with non-U.S. degrees. These people were wrong, and the reality is that immigrants are heavily selected, but the selection doesn’t result in them being particularly high-IQ on the whole. Instead, it results in them being near the American mean in terms of IQ, but also selected in other ways, like for occupation, for income, for gumption, and for other achievements. Given that IQ and different aspects of socioeconomic status are very imperfectly correlated and they can be differently related in different groups—like immigrants and natives, men and women, etc.—, it makes sense that there’s room for this to happen.

I think this result was at least somewhat predictable. We can think of immigrants as people who ‘made it’ to some achievement from groups that generally have lower IQs than Americans. This result is thus analogous to when groups like initially lower-class people make it to some level of achievement like getting an elite job or earning a PhD, and they still lag in terms of income, IQ, and other things behind initially higher-class people. The main difference is that immigrants also have considerable compensating factors in those positions because they’ve been selected multiple times in different ways thanks to the immigration system, the systems in their own countries, and so on, whereas the routes to particular kinds of success tend to be more similar for high- and low-class people from the same country. It’s a simple model.

In a sense, immigrants might not be enhancing America’s cognitive ability all that much across generations, since we should expect regression to the mean from a level that’s already not generally that high. Current immigration might boost the level a bit and it has beneficial economic effects, but it can be better.10 But if we want a different picture where immigrants definitely boost the quality of America’s human capital in a large and durable way, there are simple ways forward such as making visas like the H-1B more elite through things like compensation ranking and dropping skill-agnostic routes like the diversity visa. I can only assume everyone would be happier if the slots from less selective visas were re-routed to more selective visas like the H-1B, and doubly so if the H-1B was made less random and more selective.11

I hope we get an opportunity to put that hypothesis to the test.

But that’s just how tests are: no one makes tests with hard questions because hard questions would probably be invalid questions for large numbers of people. You can reasonably ask preschoolers to identify the silhouettes of cats and dogs, but not about the silhouette of an okapi.

If you use factor scores, the situation is even closer to ideal.

I used iterative robust model-based imputation with default settings from the VIM R package.

Restarting surveys like this and the various national freshman surveys is worth doing so that we can be better informed about immigrant and student performance, not just in terms of IQ, but much else. If we don’t have surveys like these, we’ll continue to live in the realm of speculation rather than being sure about various facts about immigrants and other groups.

Incomparable educations across countries is also supported in PIAAC, where people in countries like Japan and Norway substantially outscore those in countries like Spain and Turkey.

Do note that, while my charts show approximately the same values the article does, the precise numbers are somewhat different, and I’m not sure why. I recomputed the values from their provided data, so I’m unsure what’s behind the discrepancy.

Additionally, CodeSignal rankings seem to corroborate this result, with a larger share of top-ranked universities being American as opposed to international, but, caution, as this could be driven by differential participation.

It may be that nursing program quality degraded. This is irrelevant, as it implies the brain gain is still illusory—the training is worse and produces worse outcomes—and it still means the results don’t show increases in population ability.

It is noteworthy that the trend kept up after the U.S. closed the visa slots, suggesting selection out of nursing, or a continued general decline in student ability in the country. Unfortunately, we can’t tell the exact cause from this data.

This might even be enough to get people to agree to significantly raising the total number of slots.

In college I was friends with a lot of international students, and now in my work I deal with a lot of people who were international students, that then ended up on the H1-B track.

From my anecdotal experience, there's two classes of international students. The first class fits the stereotype of "brain gain". They are extremely intelligent, driven people, often with an ideological affinity to the United States, specifically its focus on individual excellence, hard work, freedom, and large rewards in return for great performance. These are the international students who create Startups in college, have 4.0 GPAs, and end up working at top US Banks, Law Firms or Tech Companies. When Elon Musk refers to the H1-B top 1%, these are the type of people he's familiar with in his work running elite Startups (including at one point himself).

The second class are the children of rich foreigners (or desperate parents willing to throw all their money to give their child success) who have "failed" within their own countries education system. This is particularly true in China, where the GaoCao is the final metric. No amount of studying will put you in an elite Chinese university if your IQ isn't meaningfully above average, as the GaoCao is effectively an IQ + studying test. Like the LSAT or the SAT, studying definitely gives you a leg up, but for most people there's a limit beyond which no amount of practice or studying will help you.

Having not been in the top 1% or 5%, parents throw huge amounts of money at gaming the US admission system to get into a high US university. Since Chinese eduction is so memorization-based and intense compared to the US, even average Chinese students are decently prepared to create an impressive application. Combine this with outright fraud with admission's essays, reference letters, and hiring lookalikes to sit-in on important tests (all stories I've heard from people who claimed they did this), and these underperformers get in to the US.

Some of the second class have super-rich parents, so they just live in luxury off their allowance in the US. Others, specifically those of middle class parents, have an all-or-nothing approach, where they need to get a job in order to survive, but are often woefully underprepared compared to what their credentials might suggest.

The first class of international students are the "Elite Human Capital" the H1-B system is partially designed to attract. We WANT these people, ideally all of them, from around the world, as they're the ones running the trillion-dollar tech companies that have made the US so wealthy in the past few decades. A few thousand of these people could honestly be the difference between US dominance in AI, Battery Technology, Self Driving Cars, and any other transformational technology you can imagine.

The second class of people are more difficult to deal with. The children of wealthy parents are great since they spend so much on luxury that they effectively act as a wealth transfer tool back to the US. Luxury products are usually very high margin, low labor to produce, and if a $300 meal in New York balances out a literal ton of steel from China, I think the US is getting the better end of the deal.

The mediocre students from the second class are the problem. They give all H1-B students a bad name, and generally end up underperforming everywhere they go. The ideal outcome for them is to be a below average worker in a large corporate machine that's too incompetent to fire them. They are (maybe) net-drains on the economy, but their real damage is done when they apply for H1-B on equal footing as the elite students I mention before. It's an absolute travesty that our system is giving an equal playing field to incompetent and competent people.

Whether my experience is representative, I don't know. If it is, I think a better system would be to give every high-performing student a fast-track to a Visa. Whether that's a reformed H1-B or a new category I don't know. Maybe make it conditional on any of the following;

- 2 SD above US mean in IQ

- 2 SD above US mean in starting salary

- 2 SD above US mean in educational attainment

1) any metric you establish the immigrant has a very strong incentive to game. So while these are improvements, I expect people will adjust in time to exploit the system in new ways. This is what’s happened in the anglosphere as regards Indian immigration.

2) instead of having beuracrats try to come up with formulas for what such a such a position should pay, let’s just charge a bunch of money for a visa. If you’re productive enough to cough up the money, you’re in. No guessing games, simple and pure.

Another added benefit is that it raises revenue that can compensate natives for any perceived externalities.

3) the real issue is always going to be family re-unification and birthright citizenship. Bryan Caplan told a story of a Nigerian doctor that chain migrated 150 family members.

This is another way in which “make them pay” works. If you have to pay a large sum to re-unify each family member this will put a damper on the importation of less able chain migration