The Worst Argument Against Ozempic

Unfortunately, being skinny might require effort

If you’re looking to acquire Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, Retatrutide or other GLP-1RA drugs at an extremely low price of around $15-$40 per month, see this article.

GLP-1 receptor agonists (henceforth, GLP-1RAs) are proving to be miracle drugs, but as with any miracle, they have their doubters. The doubters have developed many arguments against GLP-1RAs and the arguments vary in sophistication, but they far fail to overturn the GLP-1 value proposition. I want to briefly mention what I consider to be the worst argument against GLP-1RAs, because it is an argument that is both popular and weak.

The arguments that GLP-1RAs are bad because of a litany of side effects that lack strong empirical support, because they have side effects that are indistinguishable from the effects of weight loss more generally, or because they cause transient delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis) are among the most common, and they’re unimpressive, but neither is the argument that I consider to be the worst.

The worst genuine argument is one that commonly accompanies this chart:

Care to guess the argument? The Economist put it in words:

A… drawback, however, is that those who start taking [GLP-1RAs] are likely to depend on them for life. Stop, and the weight piles back on, just as with most conventional diets. In the first year after stopping a 2.4mg dose of semaglutide, people regain two-thirds of the weight they lost. And, as with dieting, some people even put on more weight than they started with.

The argument is that GLP-1RAs are bad… because you regain weight when you stop them? By the same logic, diet and exercise are bad because, when you cut them out, you’ll also tend to regain weight. Weight rebound after giving up exercise programs and dieting is universal, so to the extent that’s a problem for GLP-1RAs, why isn’t it also stated as a problem for everything else?

There’s a more sophisticated argument that accepts people who need GLP-1RAs might need to use them forever in order to maintain their reduced weight, but that this is dangerous for reasons. After all, the proponents of this argument claim, we don’t know about the potential long-term harms of GLP-1RAs. We know about effects since they’ve been approved (circa 2017) but that’s it, and what if being on them much longer has unexpected side effects?

This argument at least facially makes sense and it’s fine to humor it, but we have to do so in a calibrated way.

What might the long-term harms actually be? No one has provided a mechanism to guide the search and the primary mechanism of GLP-1-induced weight loss (agonism of brainstem GLP-1 neurons involved in appetite) doesn’t seem likely to be directly harmful. Why would the harms have not shown up over the past near-decade of use? They must be so unpredictable as to evade detection over a reasonably long period of time. And most importantly, what’s the counterfactual?

Every other day, a new story comes out about something that GLP-1RAs help to address, from chronic kidney disease to infertility. Given GLP-1RAs are so universally helpful, I believe we should update against them being mysteriously harmful. Additionally, we should weight the benefits versus the hypothetical costs. We know the benefits to living a life without obesity are enormous, and if I had to bet, I would say that the people taking GLP-1RAs for weight management long-term will have longer, happier, healthier lives thanks to these drugs, unless the unexpected happens and there really is a lurking harm to GLP-1RAs—a harm that has, so far, evaded detection and prediction.

In any case, the argument that GLP-1RAs are bad because you have to keep using them is hard to distinguish from the argument that exercise and dieting are bad for the same reason. It’s not an argument I humor; it’s the worst genuine argument against GLP-1RAs.

June 4th 2025 Update: Real-World Rebound Evidence

Weight regain after weight loss is, as one recent editorial put it, the “‘Achilles heel’ of lifestyle therapy in people with obesity” and “most people who lose weight subsequently regain most or all of their lost weight.” I noted above that we see this problem crop up both when people cease to engage in standard dieting and exercise as well as when people stop using pharmacotherapies from 2,4-DNP to Orlistat to modern GLP-1RAs.

The composition of regained weight tends to be like the composition of lost weight, and this holds true regardless of the speed at which the weight is lost. An additional finding is that the amount of weight lost predicts the amount of weight regained, but the proportionate regain following different levels of weight loss is similar, and the pace of weight loss fails to consistently relate to the extent of regain.

I recently noted that GLP-1RA-induced weight loss does not seem to produce exceptional muscle mass loss compared to other means of weight loss. In that sense, GLP-1RA-induced weight loss is like normal weight loss, but is it like it in turns of regain? Using the data cited out of The Economist, above, and Anderson et al.’s meta-analysis of weight loss maintenance (see here as well), let’s compare.

In a word, “yes”, there’s similar absolute regain two years after natural weight loss and coming off of Ozempic. That is also what the sum of the prior literature would predict. IF there are differences, they are very likely to be minor. But we’re missing something: real-world evidence on Ozempic rebound. In the real world, people stop and start using GLP-1RAs for various reasons, not just because people are taking off of the drug or randomized to a placebo after a GLP-1RA lead-in. This difference has been noticed in the literature.

Thankfully, Epic has now looked into this. The research team at the electronic health record company pulled together two reasonably large, observational samples of individuals who stopped taking either semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) or liraglutide (Victoza) and then showed how their weights changed over the course of a year. The results aren’t granular, but they’re still very uplifting:1

A year after quitting semaglutide, 20% of people maintained their achieved weight. But, some 44% regained weight. Of that 44%, most (59% of them) still had improved weight: their weights had not fully rebounded to their pre-semaglutide level! Possibly even more importantly, the remaining 36% continued losing weight, either mildly (47%) or majorly (53%). In short, people tended to keep the weight off, and 82% of people had improved weight a year after coming off of semaglutide. The situation for liraglutide was highly similar.

This finding should reassure everyone that ‘the worst argument Ozempic’ holds very little water as usage is still durably health-improving after people come off of the drugs. In real world settings where people choose to stop using the drugs, people might just keep the weight loss off better than after trials, and that’s wonderful because it suggests the possibility for versatile uses of the drugs.

My read is that a summation of the prior literature would lead to predicting these conclusions. With that in mind, I think we can move along to the more important conclusion for public health: how much credence should we give ‘the worst argument against Ozempic’ as a reason to preference alternative means of dropping weight? The answer depends on what you think about adherence and about how healthy it is to use these drugs long-term.

The long-term health effects seem fine and concerns with regards to those can be brushed aside barring some shocking new development. With more than a decade of safety data on various GLP-1RAs, nothing alarming has cropped up, and indeed, based on generalizing from surgical obesity interventions, understanding the underlying mechanisms of the drug, and looking at the results of trial after trial, the broad health impacts are almost-certainly positive. So let’s talk adherence.

It is much easier to get people to lose weight with GLP-1RAs than with prescribing changes to exercise and diet. It is just a fact that most people are bad at starting healthy new habits, let alone sticking to intense diet and exercise plans. To cite a well-known example, most people stop their New Year’s Resolution diets before six weeks; most people never even use their New Year’s Resolution gym memberships, and half of them expire within three months.

The standard citation on this matter defined successful weight loss as such: “Intentionally losing ≥ 10% of initial weight and keeping it off for ≥ 1 year.” Given this, rates of successful long-term weight loss are very poor: “based on this definition, approximately a quarter of overweight individuals report successfully maintaining weight loss.”

This is no surprise. Rates of attrition and nonadherence in exercise and diet studies are very high. It may even be the case that when we define adherence less by ‘showing up’ or ‘reporting in’ for interventions, but instead by monitored activity levels, adherence to exercise plans is even worse. Even people whose lives are on the line don’t have great diet adherence. Practically the only way to get good adherence is to actively put in an effort to keep people motivated while providing them with all their food. Simply put, plans may be more involved, more interactive, and many other things that could help to sustain interest, but no one has found a reliable way to achieve mass weight loss in light of people’s natural resistance to committing themselves to doing more or resisting their dietary urges, or to their proclivity for seeking dietary variety.

The weight regain prognosis for non-GLP-1RA weight loss is even worse than the success rate following semaglutide cessation observationally and in trials, and only partly because semaglutide tends to lead to larger weight loss than typical non-GLP-1RA weight loss. If we add in that people tend to struggle to achieve an initial ≥ 10% weight loss at all with non-GLP-1RA methods, then the situation without them looks all the more dire.2

So, to round this off, we have to talk about why people quit exercising and dieting, why they choose to quit semaglutide, and what can be done to serve the interests of public health. I believe I’ve alluded to the first thing, but it’s simple: people are lazy. People really do not want to stop eating or to get up and go doing strenuous exercise, for a variety of reasons. Laziness may be because obesity has made it hard to exercise, so the effort doesn’t feel worth it; laziness might be down to a psychiatric condition potentially comorbid with obesity. Whatever the cause, it’s real, and we see evidence of it in many forms. One particularly informative form is how many people elect to do more to get GLP-1RAs. There are articles aplenty out there reporting the anecdote that people are taking up second jobs to be able to pay for GLP-1RA drugs. Working another low-intensity job is evidently psychologically easier than putting down the fork or running on the treadmill.

The reasons people quit GLP-1RAs are different. Though strict adherence to diet and exercise plans is abnormal, some 70-80% of diabetics who take GLP-1RAs or SGLT2 inhibitors continue to use them on an ongoing basis over a five-year period of follow-up. This ongoing use happens despite nearly half of the individuals prescribed these drugs discontinuing them at some point. Plainly, they get off and then about half of them get back on.3

Patients with diabetes are both less likely to discontinue GLP-1RA usage and more likely to reinitiate usage compared to patients without diabetes. Among the predictors of discontinuation in both groups are being old, being Black (relative to being White), and having a lower income. Among the shared predictors of not discontinuing, we have being Asian and weight loss. Both race associations presumably reflect a considerable—but perhaps not total—degree of socioeconomic confounding, with Blacks being generally less able to pay for the drugs, and Asians being more able.

Serious side effects only predict disuse for those with diabetes, who tend to transition instead to other equivalent drugs for the purposes of diabetes management. Individuals without diabetes instead tend to ignore serious side effects at a greater rate, with their discontinuation only being linked to gastrointestinal adverse events, which tend to be transient (like GLP-1RA-related gastroparesis) and non-severe.4 For both groups, serious side effects did not predict reinitiation either way, but gastrointestinal side effects predicted less reinitiation. More importantly, weight regain predicted reinitiation. That is, if people gained too much, they sought out the drugs again and continued their weight loss journeys.

The situation observed with GLP-1RA discontinuation is one where people reach their goals, or their insurance coverage lapses, or they don’t want to pay for the drugs because they’re too expensive, or they’re among the limited few for whom the side effects are too rough and they’d prefer doing something else. The situation with reinitiation is one where people regain the ability to afford the drugs, they want to maintain their prior weight loss easily like they did when they were using, or they’re playing around with diabetes management medication.

Luckily, newer drugs like tirzepatide and retatrutide present with fewer and less severe gastrointestinal side effects and lower rates of mild side effect-related discontinuation. High drug prices should not be an issue anyway. (Need help with that? Click here.) If drug prices fall for whatever reason, then more people will begin to use the drugs continuously in the pursuit of their weight loss goals, and more people will yo-yo with their usage, jumping on the drugs to lose weight, getting off when they’re happy, and getting back on for their easy, once-weekly shots if they’re not maintaining weight loss well enough. When effective oral medication becomes readily available, usage will likely skyrocket, as many patients are afraid of needles, and the hassle of injection is a top reason for discontinuing the usage of not just GLP-1RAs, but any injectable drugs. Versions with a longer half-life are also being worked on to alleviate this problem

Now to muse about agency health policy positions and ‘the worst argument.’

If you understand what I wrote above, you can grasp the critical difference between a public health focus on exercise and diet versus GLP-1RAs as a response to the obesity crisis. The difference has to do with success rates: GLP-1RAs will cause virtually everyone to reach successful weight loss.

As we have now seen, GLP-1RAs will also allow people to maintain successful weight loss in the majority of cases. If cycling of usage is accessible and allowable, then society-wide weight loss is also readily sustainable, people merely have to get back on the drugs, likely for a short period of time before hitting their goal weight again and discontinuing, without any likely harms to their health. With generic versions of GLP-1RAs and additional price competition through the introduction of new competitors, all of this can quickly go from being fiscally burdensome to think about to fiscally lifesaving, providing potentially trillions of dollars in indirect financial benefits to the government and to businesses over reasonable timeframes.

A focus on exercise and diet, on the other hand, will almost-certainly fail. These things have been the focus of almost every health agency for ages, and they have done virtually nothing to stall the rise of obesity. Recreating the food supply from the ground up is a potentially viable alternative to mass GLP-1RA usage, but it’s strictly inferior for reasons like:

Confusion: the food supply is not tainted by toxins, but this motivation is common.

Liberty: taking away people’s choices may reduce obesity, but it’s un-American.

Cost: this would be far more expensive than simply buying out the patent for a drug like tirzepatide or semaglutide and allowing generics to be sold.

Political Feasibility: it’s very likely that whatever limited changes could happen would be met with massive resistance from across the aisle, from companies, and from the population at-large. No one wants to deal with the fallout of recreating the food supply to quash obesity, and realistically, no health authority can do this without causing major problems and unintended side effects that outweigh the benefits of their actions.

Actual Feasibility: With the options for reform of the food supply on the table, it is unlikely that obesity can be tackled by health authorities. They cannot meaningfully eliminate available dietary diversity or limit the sizes of the dishes people eat, and if they raise prices substantially to reduce consumption, then we return to political feasibility concerns, as they’ll swiftly find themselves on the way out of their positions in government, with their party taking a hit for it too.

In short, ‘there will be weight regain after stopping Ozempic’ remains the worst argument against Ozempic and other GLP-1RAs because the same argument strongly applies to every other form of weight loss, and perhaps it applies more extremely. The argument will likely continue to be the worst common argument against GLP-1RAs so long as people are unwilling to acknowledge that they are safe and effective or that there is no world accessible to us in which diet and exercise-based policy turns on its head and begins to actually work. We either have GLP-1RAs and drugs like them incorporated into health policy, or we carry on with the obesity crisis.

The ‘worst argument’ is baseless, it is counterproductive for moving the needle towards meaningful changes in health agency policy positions, and for altogether too many who make it, it is nothing more than a coping device that masks malformed anti-pharmaceutical conviction.

June 20th 2025 Update: A Review of Trials

On June 9th—five days after my last update—a new systematic review and nonlinear meta-regression of weight regain after quitting GLP-1RAs in trials came out. Their result was as follows:

The findings of this review indicate that there is significant weight regain following cessation of GLP-1RAs. The meta-regression shows that after 1 year of treatment withdrawal, participants regain 60% of the weight they lost during treatment. The trajectory of regain is nonlinear and decelerating in nature, with an initial rapid recovery followed by a gradual tapering off and eventual plateauing. Notably, the estimated plateau is below the pre-treatment baseline weight, indicating that some beneficial effects may persist at the population level [emphasis mine] beyond 1 year after cessation, potentially indefinitely based on model extrapolation.

Or, graphically:

In brief, this review (see also: here, here, here, and here) supports the magnitude I estimated above—although this not terribly impressive given the partially overlapping data—and the sustainability of a considerable degree of post-discontinuation weight loss. The fact that weight loss after GLP-1RA pharmacotherapy seems to be durable at a smaller scale than the maximal achieved weight loss is still quite heartening given the physiological benefits of even modest amounts of weight loss. Given how achievable weight loss seems to be for the overwhelming majority of people who are prescribed GLP-1RAs, this means that those benefits can be realistically achieved society-wide.

Hurrah!

September 15 2025 Update: Two-Year Rebound Evidence

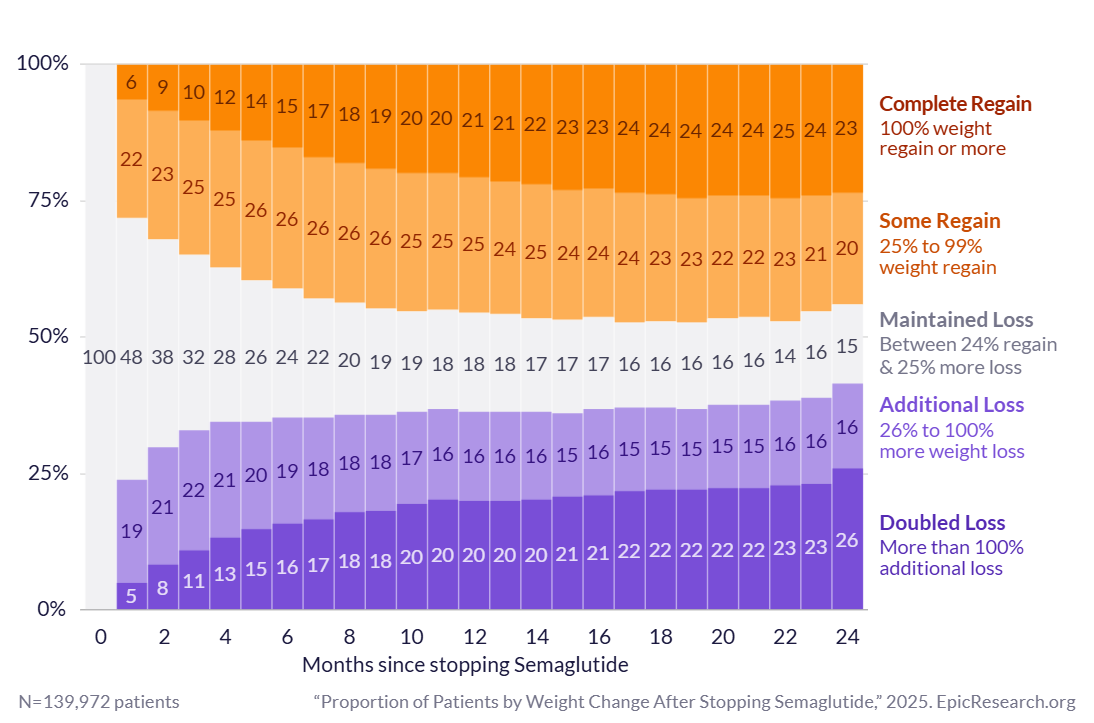

Epic has updated their analyses of weight regain. Their analysis for semaglutide now has a 6.9-times larger sample and goes to two years instead of stopping at one year. That result is even more reassuring about the lack of an issue with weight regain after stopping semaglutide. Why? Because regain practically stopped at one year and the whole sample stabilized! Compare this to the chart above; it’s a heartening result:

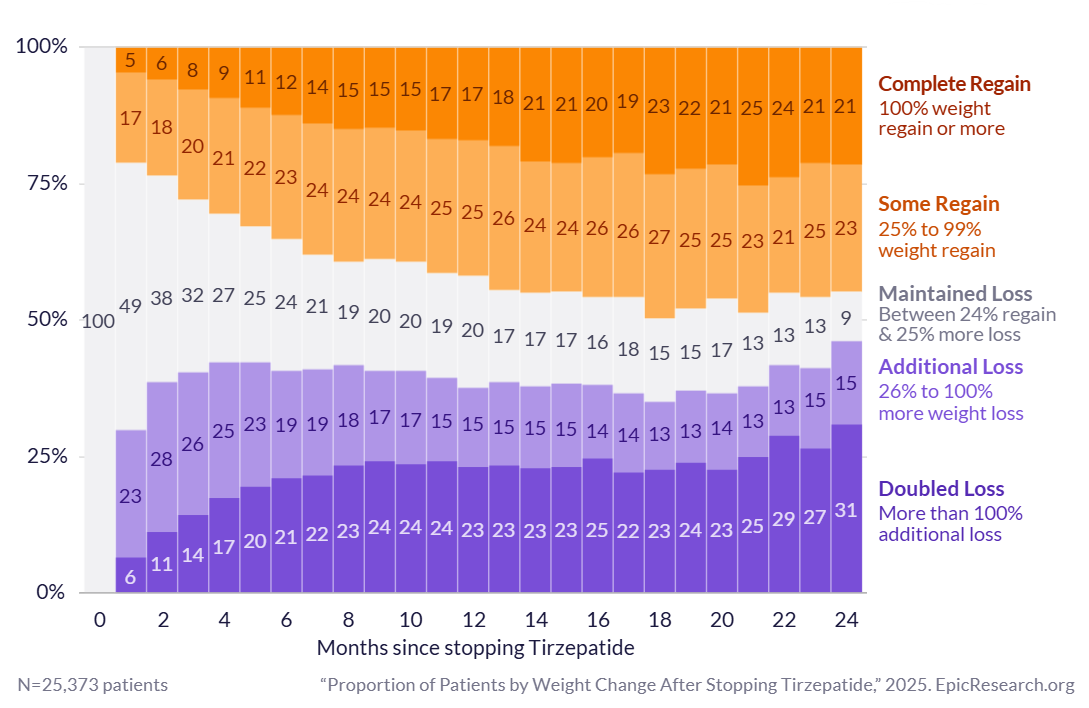

The other thing this update adds is results for tirzepatide, the more powerful approved GLP-1RA. The sample for this is much smaller than the new semaglutide sample, but it is still about 25% larger than the earlier semaglutide sample, so it’s nevertheless quite large. The results for tirzepatide are similar: people mostly kept the weight off; moreover, a marginally smaller percentage had only some regain instead of complete regain. More interestingly, the trajectories of regain seemed to stabilize later. For tirzepatide, there was stabilization around fourteen rather than twelve months, but at the same time, there sort of wasn’t. Look at the increasing rates of weight loss after a year:

In short, what we have here is what we had before: evidence that GLP-1RA-based weight loss is defensible. In fact, in both trial and real-world examples, people seem to, respectively, approach an asymptote, and definitely hit one. Perhaps as we get longer-term data from trials, we’ll see these results fully converge and the Worst Argument Against Ozempic (and other GLP-1RAs!) can finally die off.