Ozempic and Muscle Mass

Are GLP-1 drugs causing excess muscle loss compared to non-pharmacological weight loss?

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here. If you’re looking to acquire Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, Retatrutide or other GLP-1RA drugs at an extremely low price of around $15-$40 per month, see this article.

There’s a loud minority online that hates the idea of GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs (GLP-1RAs) like Ozempic and Tirzepatide. They don’t like that they allow people to ‘cheat’ their way to weight loss, that the drugs make it ‘too easy’ to lose weight. The idea that people can inject a simple fix to their problems or that a drug can be unambiguously good just doesn’t sit well with them, so they invent and latch on to bad reasons to dislike GLP-1RAs. They make claims like:

GLP-1RAs don’t work because you have to keep on them, just like how you have to keep exercising and dieting to maintain weight loss normally.

GLP-1RAs cause thyroid cancer, even though that association doesn’t seem to be supported.

GLP-1RAs are making people blind on a staggering scale, even though that’s implausible and seemingly untrue.

Not one of the numerous alleged, major downsides of GLP-1RAs has held up to scrutiny so far, and it’s not clear why they would when the trial results so clearly show tolerability, that the drugs have been in use for long enough and with enough prescriptions for major downsides to be apparent, and that the mechanisms behind the drug are so benign and commonplace. The mechanism in question is neural GLP-1 agonism, and we know that operations that create relatively high levels of endogenous GLP-1 production—like Roux-En-Y gastric bypass—are safe, meaning that there’s a large amount of excellent, long-term data to reassure us that GLP-1RAs should be too.

One popular argument against GLP-1RAs is that they lead to excessively high muscle mass loss compared to standard, non-pharmacological weight loss. Some people have even taken this so far as to claim that GLP-1RAs lead to more muscle than fat loss. Both points are difficult to credibly support, but there is at least something intuitively sensible about the first claim even if a pharmacological mechanism is absent. A pretty apparent fact is that the people who use GLP-1RAs tend to be lazier: they tend to exercise less and eat worse than people losing weight the traditional, non-drug assisted way. That could have predictable consequences for the ratio of muscle to fat loss, or so the logic goes.

Whether the logic actually holds is another matter.

Claim #1: Do People Lose More Muscle Than Fat?

The claim here is that people cut weight with GLP-1RAs primarily by losing muscle rather than fat, thus worsening body composition after drug-assisted weight loss. This position is not supported empirically. In each trial, the opposite is true: people lose more fat than muscle, improving their body composition as they lose weight.

In a major trial of Semaglutide, the treatment group lost an average of 8.36 kilograms of fat and 5.26 kilograms of lean body mass. The placebo group lost an average of 1.37 kilograms of fat and 1.83 kilograms of lean body mass. The relative contributions of fat to weight loss were 61.4% for the GLP-1RA group and 42.8% for the group losing weight with a placebo.

In a major trial of Tirzepatide, the treatment group lost 33.9% of their total fat mass and 10.9% of their lean mass, versus 8.2% and 2.6% for the placebo group. Both outcomes were favorable, but the treated participants fared better: “The ratio of total fat mass to total lean mass decreased more with tirzepatide (from 0.93 at baseline to 0.70 at week 72) than with placebo (from 0.95 to 0.88).” Similarly, in a relatively short trial of Retatrutide (Poster-474), participants saw considerable weight loss which was two-thirds fat and one-third lean.

Similar ratios are observed in different trials and these results are entirely typical across the literature. The only net unfavorable compositional result came from a trial of a less effective, daily-dosed older generation of GLP-1RA drug, Liraglutide. That failure was a narrow one (60% lean mass loss) in a very low-power substudy which also produced the nonsensical result—which failed to replicate—that a higher dose led to less weight loss.

Claim #2: Is the Muscle Loss Ratio Unusually High?

The claim here is that GLP-1RAs cause more muscle loss than would be expected given the same amount of weight loss done without pharmacological assistance, such as through using diet, exercise, or bariatric surgery. A simple way to answer this is to plot body weight loss versus lean body mass loss across different intervention regimes conducted on similar populations. That was recently done in a paper in the journal Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

The data here contains considerable noise, but the picture is nevertheless clear: at similar levels of total body weight loss, diet, GLP-1RAs, and bariatric surgery produce clinically comparable and statistically indistinguishable reductions in lean body mass. This fact has been pointed out in GLP-1RA trials; for example:

Participants treated with tirzepatide had a percent reduction in fat mass approximately three times greater than the reduction in lean mass, resulting in an overall improvement in body composition. The ratio of fat-mass loss to lean-mass loss was similar to that reported with lifestyle-based and surgical treatments for obesity.

But this does not actually answer the claim because it’s about muscle loss. Lean mass measurements are a great proxy for muscle, but lean mass is not just muscle, as it also includes water, bone, and other tissues, in addition to fat infiltration.1 There is, however, one brand-new study that does provide an answer using MRI-based measurements from the SURPASS-3 trial of Tirzepatide and from the U.K. Biobank.

The study looked at individuals in the large and popular U.K. Biobank cohort and assessed the relationship between non-pharmacological weight loss and muscle loss so that ‘normal’ weight loss could be compared to the weight loss in a matched cohort that lost weight using GLP-1RAs. The relationships in either cohort, as it turns out, were high and statistically indistinguishable:

This, however, does not inform us enough alone about whether there was more or less muscle loss, as it could have been the case that the intercepts differed. To get to that answer, the amount of muscular volume lost at a given amount of weight loss has to be compared directly. The answer from that analysis was favorable: those on Tirzepatide lost 0.04 liters more muscular volume at the same level of weight loss, which is both clinically unimportant and was statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.22).

Claim #3: Do GLP-1RAs Produce Muscular Dysfunction?

We now know that GLP-1RAs produce more fat loss than muscle loss and that the muscle loss from GLP-1RA-induced weight loss is comparable to the muscle loss that comes with lifestyle-based weight loss and from surgery. But now we have to ask: do GLP-1RAs make people unusually weak? It’s one thing to maintain muscular volume, but it may be quite another to maintain muscular quality.

There are considerable reasons to disbelieve the claim that muscular dysfunction follows from GLP-1RA-induced weight loss. The evidence above indicated that muscular volume is maintained, and that alone is very strong evidence that this belief is unfounded, but it is not itself dispositive. In the comparison between Tirzepatide-based weight loss and weight loss in the U.K. Biobank, additional evidence came in the form of observations about fat infiltration.

Fat infiltration, or myosteatosis, refers to the condition where fat gets in and between muscle fibers. This happens to everyone to varying extents, and it’s particularly marked with age. Moreover, it is strongly related to reduced strength, and increases in it seem to cause frailty and physical weakness. More importantly, reductions are accompanied by improved physical functioning. There’s high-quality documentation of this fact based on individuals who have received Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses. Their operation did cause weight loss (-30%), did cause fat loss (-48%), and did cause both lean mass loss (-13%) and reductions in absolute strength (-9%). However, relative strength increased by a much more substantial margin (+32%), and this improvement came with significant improvements in physical performance measures, like improved walking speed and heightened physical activity levels.2

This is what is expected with any intentional weight loss efforts aimed at improving body composition and weight level. That should not come as a surprise since fat genuinely impedes muscular function. Relatedly, in individuals experiencing disease-related wasting and among those with metabolic disorders, fat infiltration tends to increase as weight declines, suggesting our eyes aren’t playing tricks on us and that those individuals are experiencing unhealthy weight loss.

Here’s the kicker: fat infiltration falls with GLP-1RA-induced weight loss, as it does with non-pharmacological weight loss. This finding holds both compared to a control drug (shown below) and compared to the weight loss in the U.K. Biobank sample (-0.42pp, p < 0.0001).3 Therefore, we should have it as our prior that this sort of weight loss is not unlikely to improve rather than degrade muscular function, given everything else we know.

We can take this reasoning several steps further by noting, for example, that there is no apparent excess reduction in metabolism after taking GLP-1RAs, indicating that the weight loss is metabolically healthful. Or, to take things to their logical conclusion, we could simply look at what participants in trials report about their physical functioning. That means reporting significantly fewer physical limitations in daily life and otherwise improved physical functioning and even quality of life.

One could reasonably say that participants are overhyping the benefits to quality of life or physical functioning, but given all the other evidence, that argument rests on unsolid ground and it would be more reasonable to claim that the changes are real and correctly being observed by patients. This is even more strongly supported by observations regarding health, like those based on the reductions in cardiovascular risk factors, improvements in lung function, and even based on reported social improvements. Social improvements, I feel, should be viewed as indications of health improvements, since if people are socializing more, are going out more, and are off their couch in general, they’re probably doing other things that are more healthful and which were more difficult when they were fatter.

All lines of evidence point to GLP-1RAs improving rather than worsening muscle quality and physical functioning. Though there is reason to be concerned about individuals who are at-risk for sarcopenia using the drugs when they should not, that is not an indictment of GLP-1RAs in general use or mechanistically.4 It is, instead, a point of caution doctors should keep in mind when making the choice to prescribe these drugs.

Strong Priors: Weight Loss is Therapeutic

On the basis of the existing evidence, we can confidently state this: GLP-1RA-induced weight loss does not appear to be unique except in as much as GLP-1RA users are self-selected. With this statement of the evidence in mind, the weight loss that people are undergoing using GLP-1RAs should be regarded as health-promoting as much as weight loss in general is.5

Concerns about induced frailty and so many other alleged side effects of GLP-1RAs run counter to the evidence and routinely lack any semblance of biological plausibility or any sort of statistical credibility. If I had to bet, that will remain true and scientifically unsupported concerns will continue to dominate the GLP-1 debate.

June 18th 2025 Update: The COURAGE and EMBRAZE Trials

Several companies are developing products to reduce the amount of lean mass loss that occurs during GLP1-RA-induced weight loss. While this effort does not seem justified based on the existence of excess GLP-1-RA-related lean mass loss, it’s still justified for the reason that it’s generally good to lose less lean mass. Furthermore, if people fear excess lean mass loss with GLP-1RAs, regardless of that fear’s reality, a company might be able to profitably sell something to address that concern, which could be good for its bottom line. It’s hard to blame companies for exploiting this fear.

Regeneron (COURAGE) and Scholar Rock (EMBRAZE) recently released preliminary phase II trial results showing the success of their myostatin inhibition-based approaches. Without inhibitors, those in Regeneron’s semaglutide weight loss group dropped 34.5% lean mass and those in Scholar Rock’s tirzepatide weight loss group saw 30.2% lean mass loss. These were, respectively, nonsignificantly better and worse than the major trials cited above. Inhibitors seemed to be tolerated well and they did reduce the percentages of weight loss that was lean. The fat-free mass loss percentages in these trials were not significantly different or clinically distinct from the traditional loss range given by the well-known “Quarter Fat-Free Mass Rule”. Given the relative laziness of these users compared to people undergoing normal weight loss, there seems to be basically nothing abnormal here, consistent with the results presented above.

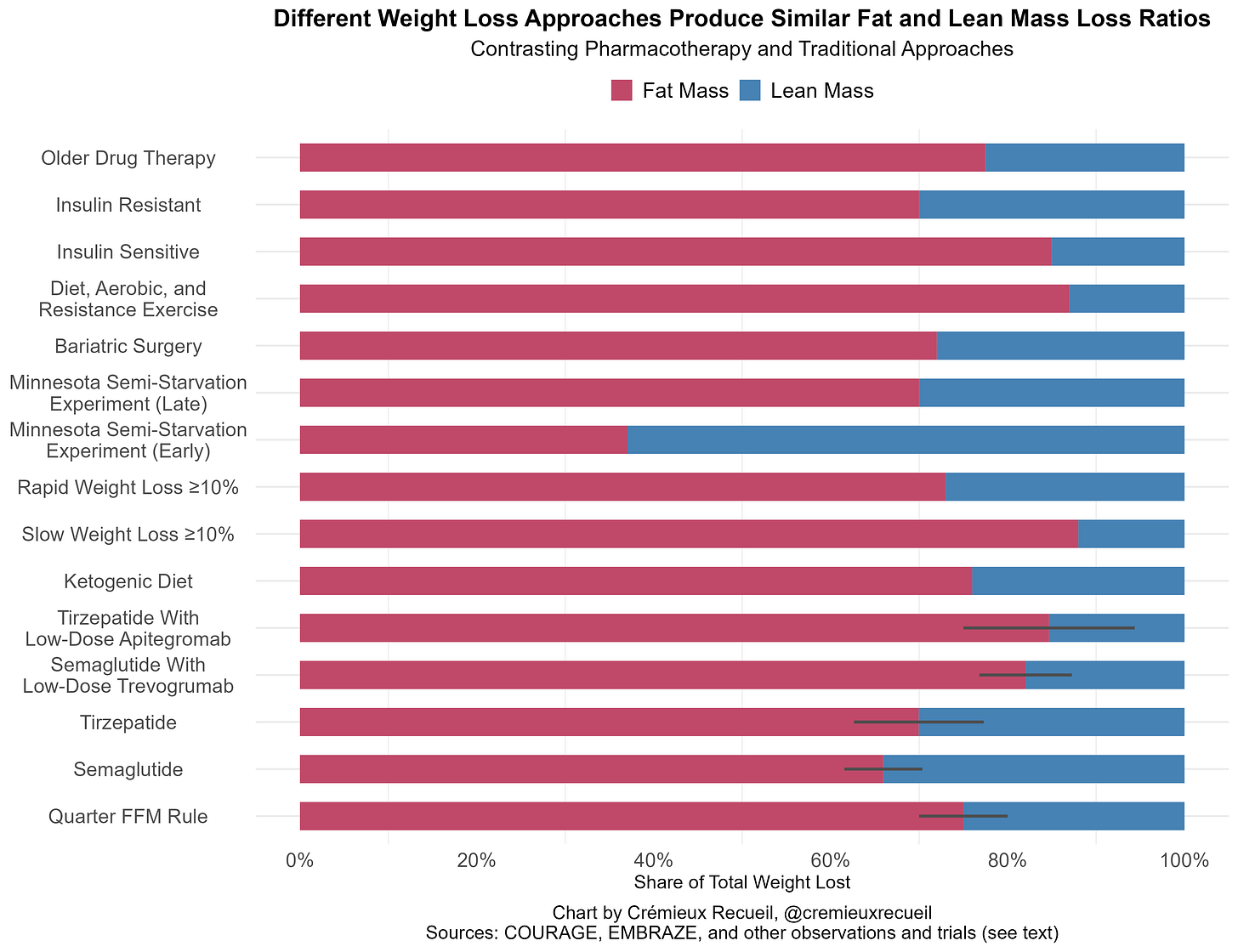

If we throw together percentages of lean mass lost with ketogenic diet, the traditional fat-free mass loss rule (25%, 20-30%), the COURAGE and EMBRAZE trials, rapid and slow “successful” weight loss, bariatric surgery, the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment results from Keys’ The Biology of Human Starvation stratified by weeks 1-12 versus 12+ (see discussion here), as well as typical values for older pharmacotherapies like orlistat and non-incretin agents, dieting in insulin-sensitive versus resistant subjects, people undergoing typical combination diet, aerobic, and resistance exercise regimes, and so on, then we’ll have some healthy comparisons. I’ve omitted values for crash diets, ‘good practice’ high-protein very-low-calorie diets, mixed diet plus aerobic and resistance exercise regimens, and things that have not held up well, like chromium picolinate supplementation, as the heterogeneity in the literature is just too much to deal with.

The usual caveats for this domain apply, as there is a lot of heterogeneity in sampling, there’s error in measurement, bias in publication, and so on, so take this all with a pinch of salt and imagine that the presented numbers are point-estimates for reasonably-wide ranges. On that point, I don’t include confidence intervals for every value, and the Quarter FFM interval is the typically-cited range. Without further ado:

For most people, there’s nothing alarming about the composition of weight loss from GLP-1RAs when compared to a sampling from the wider literature. These loss ratios seem to be fine and at a level where weight loss is certainly healthful, especially for individuals suffering from serious obesity. With that said, semaglutide may be statistically—but not typically clinically—worse than tirzepatide across the published literature, and perhaps low-dose myostatin inhibitors could make both superior to most other weight loss approaches, if not in terms of the total lean mass loss ratio itself, then in terms of that in combination with the feasibility of treatment.

Though I did not illustrate it, Regeneron’s high-dose trevogrumab and garetosmab therapy was superior in terms of lean mass loss to almost everything on this chart and it was superior to everything on this chart feasibility- and absolute loss in a given amount of time-wise, but garetosmab tolerability left something to be desired.

The results of the COURAGE and EMBRAZE trials are encouraging regardless of the validity or lack thereof of worries over excess lean mass loss with GLP-1RA-induced weight loss.

June 21st 2025 Update: A Systematic Review of GLP-1RAs

There’s a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on GLP-1RA effects on body composition and its results are worth mentioning.

Across twenty-two randomized controlled trials of varying lengths, drugs, and dosages, GLP-1RAs were associated with 3.55 kilograms of lost weight, 2.95 kilograms of lost fat mass, and 0.86 kilograms of lost lean mass. You might notice that 2.95 + 0.86 = 3.81, not 3.55, so something is amiss. You’d be right: all the estimates aren’t matched; not every study reported each outcome, so there’s a bit of noisiness. But, using these numbers, we can get a plausible range of values for the lean mass percentage. If we use the fat mass loss as a percentage of the overall body weight loss, GLP-1RAs are associated with 16.9% lean mass loss, and if we use the lean mass loss, the number is 24.2%, and if we reason from the sum of the lean and fat mass loss numbers, the lean percentage is 22.6%. Per the authors, lean mass loss generally comprised “approximately 25% of the total weight loss”, consistent with the Quarter FFM Rule.

If we look specifically at the results for top-line GLP-1RAs in use today, we see that they had reports on 15 mg weekly tirzepatide, 1 mg weekly semaglutide, and 14 mg daily oral semaglutide, in addition to reported on liraglutide given at dosages of 1.8 or 3.0 mg. Comparing the lean mass percentages for these different drugs is possible, and I’ve added a chart of this in this footnote6, but I want to advise that I don’t think simply comparing fat loss percentages without contextualization is the right approach. The reason is, different trials led to different total weight loss, and total weight loss moderates the extent of lean mass loss. If you lose enough weight, you will eventually lose both more and a higher percentage of lean mass. It’s unclear if this happens in the range seen in these studies. Indeed, one could easily argue the opposite, but for low amounts of lost weight, because the first weight to go is lean mass in the form of water weight. So, we’ll isolate our view to the endpoints of trials with significant and positive weight loss.

As with the overall results, there is some imprecision due to unmatched estimates, so keep that in mind. Tirzepatide (15 mg/week) led to 10.81 kilograms of lost weight, of which 8.75 were fat and 1.84 were lean. Taking the lean percentage from the sum, we get 17.4%, or from the total based on fat mass lost, we get 19.1% versus 17.0% reasoning from fat and lean mass losses, respectively. For semaglutide (1mg/week), there were 6.24 kilograms of total weight lost, of which 4.37 were fat and 1.22 were lean. The same numbers were 16.4%, 30%, and 19.6%. For oral semaglutide, total losses were 2.60 kilograms, with 2 kilograms of fat and 0.60 lean, for 23.1% lean mass losses.

If we take all the aggregated treatment effects with weight loss in this review, we can assess the slopes for fat and lean mass loss versus total weight lost straightforwardly. By contrasting these slopes, we can gather an expectation about lean mass loss as weight loss grows.7

In general, this weight loss seems to come with roughly one-fifth lean mass loss, and the slopes aren’t driven by either the tirzepatide datapoint or the estimates with nonsignificant total losses. Even removing all of them doesn’t really change the picture. The authors of the paper used the individual study point estimates when they did a meta-regression similar to this, and they found slopes of β = 0.7 and 0.09 for fat and lean mass loss, respectively. Their estimates were even more favorable towards GLP-1RAs than the estimates I made from the aggregated numbers. In both cases, linearity seemed tenable enough.

This review provided substantial and clear evidence: GLP-1RA-induced weight loss does not appear to produce meaningfully different compositional effects than typical weight loss, as represented by the Quarter FFM Rule.

June 23rd Update: The Age of Mass-Market Monoclonals?

Today, Eli Lilly gave an incredible presentation at the ADA 2025 meeting. They showed the results of treating people with their activin type-II receptor inhibitor, bimagrumab, without and without the addition of semaglutide. This trial was allocated 55-56 people per arm to a total of nine different arms, and the efficacy results were nothing short of stupendous. Going solely off of what was presented:

There are a few results to mention here. Let’s go left-to-right:

Bimagrumab on its own led to weight reductions, as seen in an earlier phase II trial.

These reductions were entirely due to the loss of fat.

Meaning, muscle was entirely preserved in bimagrumab-only treatment.

Semaglutide alone led to a proportion of fat loss not distinguishable from the Quarter FFM Rule. It did not lead to excess lean mass loss.

Combination bimagrumab and semaglutide led to compositional improvements.

Proportionally less lean mass was lost than is observed in typical weight loss.

Proportionally less lean mass was lost than is observed in weight loss with good control over exercise and diet.

The pace of weight loss was accelerated over semaglutide-based expectations.

The dosage of bimagrumab (10mg/kg in low-dose arms or 30mg/kg in high-dose arms) was unrelated to the extent of lean mass preservation, only to weight loss.8

This fits with, but, at this dosage, fails to confirm the theory that much lower dosages could still deliver substantially improved lean mass preservation.

Reassuringly, bimagrumab did not seem to produce ‘useless’ muscle, as it was at least strength-preserving, and potentially strength-enhancing.

Physical function was improved.

Grip strength was sustained or improved.

Leptin levels fell by more and adiponectin levels increased by more among the bimagrumab users.

Proxied inflammation levels fell more with bimagrumab than with semaglutide alone.

Now, onto the bad parts.

Firstly, there’s a statistical caveat here: Eli Lilly primarily presented TOT instead of ITT estimates. These are more favorable to efficacy judgments and they make comparisons with other plots in different studies more difficult. Moreover, the difference may be particularly meaningful in this case, because high-dose monoclonal antibody treatments often come with a lot of side effects. This was no exception, although it should be noted that none of the side effects were “serious”, meaning becoming life-threatening.

The side effects that were above and beyond the typical side effects seen with semaglutide were:

Muscle spasms (~50-75% of the bimagrumab samples versus ~6% for placebo and ~9-13% for semaglutide)

Acne (~34-55% of the bimagrumab samples versus ~4% for placebo and 9-11% for semaglutide)

Lipid profiles showed an atherogenic shift.

HDL levels decreased transiently in all weight loss groups, but they decreased more for bimagrumab users, and they only returned to baseline by 48 weeks for them, whereas they returned to baseline by 24 weeks for semaglutide users.

For all treatment groups, HDL levels increased above baseline to a comparable degree after the trial was through, so this is not an ongoing concern.

LDL levels experienced a sustained roughly 10% decline for the semaglutide-only groups, but they experienced a sizable increase for the bimagrumab groups, ranging between 15% for the highest-dose group to 30% for the high-dose bimagrumab-alone group.

The levels in the high-dose groups that took semaglutide moved back to baseline by 24 weeks after treatment.

Levels for the high-dose bimagrumab-only group dropped down to +18% by 24 weeks after treatment, and in both of the bimagrumab groups using low-dose semaglutide, they seemed to not move at all post-treatment, sticking around at ~13-16% above baseline.

All the caveats noted, this antibody treatment clearly has major potential and possible mass market appeal.

Acne is generally mild and manageable, and muscle spasms are also generally mild, and they’re usually transient. Both are also side effects seen with anabolic steroid usage, and you can just ask bodybuilders how they deal with those issues: they’ll usually say they’re fine, manageable, and worthwhile. (Imagine how much this will help bodybuilders with cut and bulk cycles!) Since steroid users tend to be younger and hardier, they might not even care about the muscle spasms at all, but these could be a bigger issue for the general population and especially for the elderly. The lipid issue is also something seen with anabolic steroid usage, and it is also manageable, but definitely more pesky. The atherogenic effect of LDL accumulates with time, so therapy with bimagrumab might benefit from statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, or simply not going on for a very long time. Bimagrumab definitely benefits from being paired with semaglutide to control the atherogenic risk, and it may also benefit if there are bimagrumab-related glycemic control issues down the line. This atherogenic issue might present an issue for the people who want to use bimagrumab to gain muscle, but they are neither here nor there. If there are other side effects like alopecia, those have not come up to my knowledge, and they will need to be investigated. That sort of thing may be a phase IV issue.

In the study’s high-dose bimagrumab and semaglutide arm, 94% of participants achieved at least a 30% reduction in fat mass, so given you can very likely just come off to get rid of the acne and muscle spasm side effects while sustaining your weight well due to the preserved muscle mass, a huge number of customers will find this to be worthwhile. When this moves to subcutaneous dosing and the price drops, I am certain we’ll see lots of people clamoring to use this product and products like it. Eli Lilly is also running a trial with tirzepatide instead of semaglutide; it’s likely that trial will see even smaller reductions in lean mass and even greater weight loss, with fewer gastrointestinal side effects.

Best of luck to Eli Lilly and to every other pharmaceutical company trying to make this a reality. What they’re doing here is nothing short of amazing. They are making weight loss an injectable, and making being—in terms of being muscular and low-fat—increasingly trivial. If companies like Eli Lilly, Regeneron, and Scholar Rock succeed, then Americans will become much more attractive, athletic, and healthy, fast.

I hope to see more work done in this area to alleviate the issue of lean mass loss with weight loss, even though this study and studies like it show that it’s not a problem that’s unique to or accentuated in GLP-1RA-induced weight loss.

Will I Keep Updating This Post?

There will be no more large edits unless something big happens. The evidence is clear enough and anyone still in denial about the fact that GLP-1RAs do not lend themselves to excess lean mass loss is fighting an uphill battle against mountains of evidence.

I will likely only be doing small edits below, largely by bullet point, as new results come along. I also may go back and edit the parts on Regeneron’s, Scholar Rock’s, and Eli Lilly’s results once the papers are published for the preliminary trial results I covered.

Short Updates

June 24, 2025: A subscriber sent me Locatelli et al.’s article arguing that adding exercise to incretin-based therapies would help to reduce the extent of lean mass loss.

The data they cite overlaps considerably with what I cite here, so not much new on that front. The conclusions they reach are about benefits from exercise also valid, and if you scroll up to the weight loss method vs. compositional change chart I made, you can see evidence for it. As public health advice, their conclusions are not very useful, because motivating people is a major part of the issue with weight in the first place. But there might be utility in telling people that exercise can offset lean mass loss, or that the lean mass loss ratio is broadly similar between GLP-1RA therapy and other forms of weight loss.July 1, 2025: Look et al. reanalyzed SURMOUNT-1 and found that individuals in the tirzepatide and placebo groups lost 21.3% and 5.3% of their body weight, respectively, while both groups lost about 24% of their weight as lean mass. The tirzepatide group lost 24.3% as lean mass and the placebo group lost 24.1% of theirs as lean mass; these amounts were not significantly different.

Sargeant et al. was one of the earliest meta-analyses of the compositional effects of GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is, and they found that the proportion of lean mass loss was “consistent with diet-induced weight loss and bariatric surgery.” The one semaglutide trial included in their meta-analysis found 22% lean mass loss and 70% fat mass loss. Results were not as good for the SGLT2is.

Chun et al. analyzed the compositional effects of semaglutide that had been compounded with vitamin B12. They found that participants in their study lost an average of 34.9% lean mass and 21.5% of skeletal muscle, more specifically. Lean mass is typically on the order of 55% muscle, so the muscle proportion of mass losses here were nonsignificantly exceptional, at 61.5% of the lean mass losses. Critically, I don’t know how much to trust this study’s results, as it didn’t use an MRI or a DXA scan, but instead, bioelectrical impedance, which is less reliable.

Dubin et al. did another review of weight loss composition with GLP-1RA-induced weight loss. For oral semaglutide, they cited a study finding that 4% of the weight loss was lean, and for injectable semaglutide, they cited four studies that found lean percentages of 22%, 40.3%, 38%, and 14.2%. For tirzepatide, they cited two studies, which found lean mass loss proportions of 14.2% and 32.6%. For other GLP-1RAs, they cited some studies with results that are definitely worth mentioning. For example, one of the liraglutide studies from 2009 found increasing lean mass loss proportions with increasing dosages, from 33.3% at 0.6 mg daily doses to 40% with 1.2 mg to 46.9% with 1.8 mg. They also cited a liraglutide study that found 3.0 mg daily without exercise came with 38.6% lean mass loss versus 24.7% with exercise, but keep in mind, the sample sizes were only 41 and 45 for those groups.

Jiao et al. did yet another meta-analysis of GLP-1RA-induced weight loss, including many unmatched studies. Their general result was that usage was associated with losing 2.25 kilograms of fat mass and 1.02 kilograms of lean body mass, for a 31.2% lean mass share. Using just semaglutide studies, the share was 24.2%, and for tirzepatide, it was 6.8%. Oddly, those numbers for tirzepatide were matched, and for semaglutide, they were mostly matched.

In meta-regressions, no factors from study duration to age to male percentage of the sample to BMI to HbA1c changes to SBP to waist or hip circumference to body weight to the lean or fat mass change differences ended up being significant moderators of the extents of fat or lean mass loss.Coskun et al. provided more complete reporting on the trial results already presented in Poster-474, mentioned above. Dirksen and Madsbad commented on those. There’s nothing new here if you were already familiar with the poster and the reporting that’s happened on it.

July 3, 2025: Anastasilakis et al. reviewed the effect of GLP-1RAs on a different type of lean mass: bone. Reviewing preclinical and clinical data on bone metabolism, they found that evidence was most consistent with protective effects of GLP-1RAs, with there being evidence for osteoblast stimulation and osteoclast inhibition.

July 22, 2025: Liu, Weeldreyer and Angadi provided a narrative review on GLP-1RA use, muscle mass losses, and cardiorespiratory fitness changes. If you’re unfamiliar with narrative reviews, they are essentially just opinion pieces published in scientific journals and they generally have as much value as statements of opinion. This is no different.

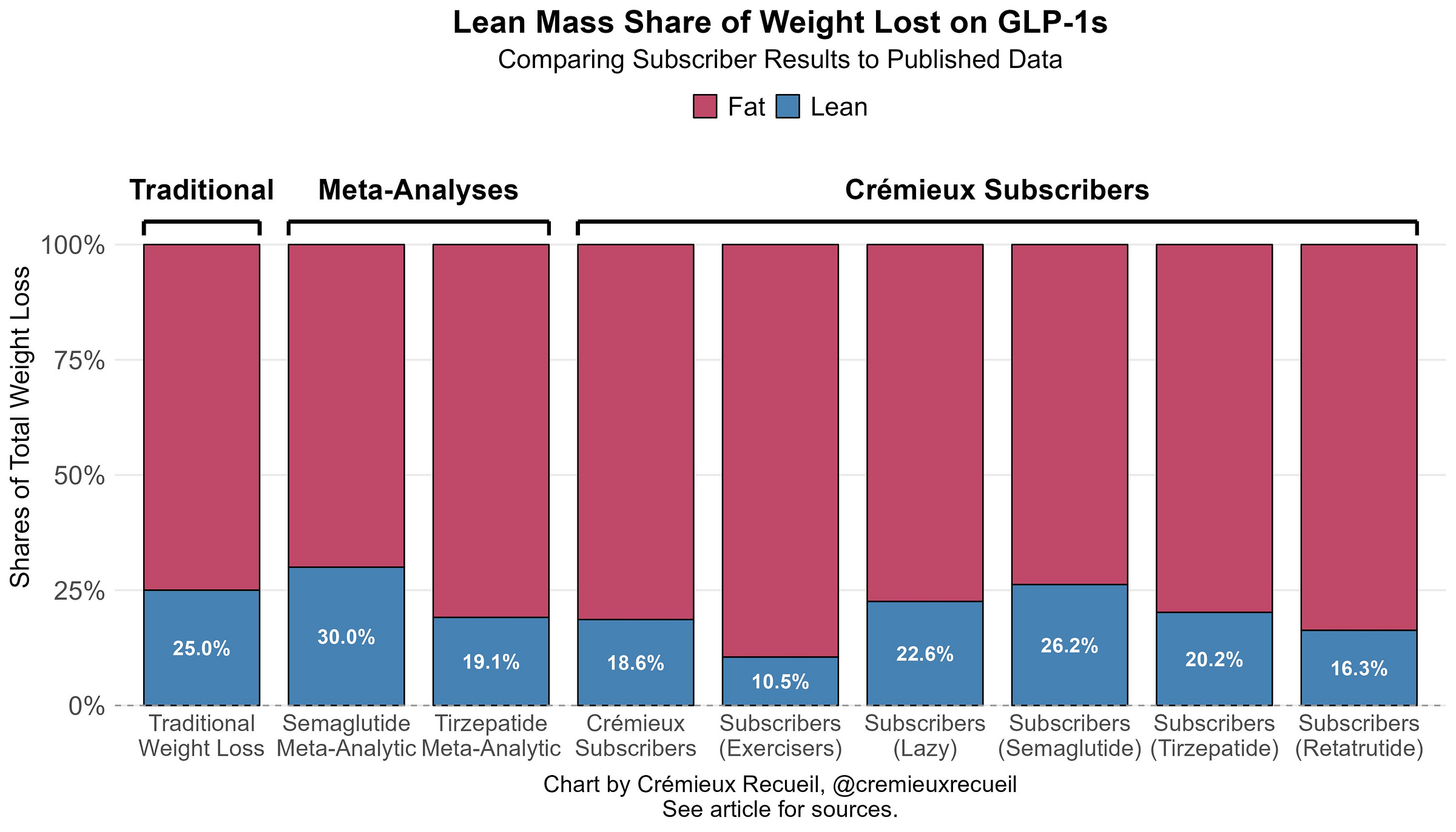

The authors did not review anything not already reviewed here, and they argued that, though there were a wide array of improvements seen with GLP-1RA use, benefits to certain measures of cardiorespiratory fitness have not yet been shown. While debatably true, it’s also true that people haven’t shown GLP-1RAs cause people to sprout rabbit ears yet. Nevertheless, benefits to things related to cardiorespiratory fitness have definitely been demonstrated. For example, heart failure patients can walk further in six minutes after using GLP-1RAs.October 25, 2025: 440 of my subscribers provided me with composition data. Here’s how it looks:

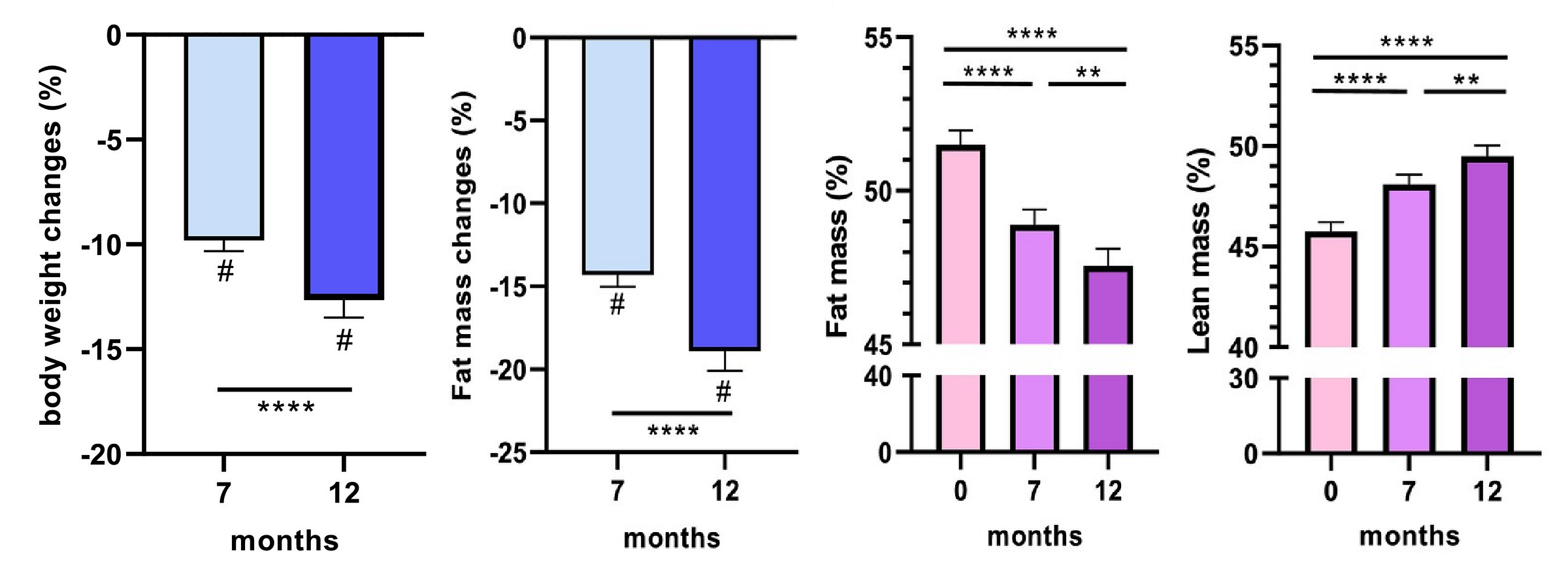

Alissou et al. presented the results of the one-year SEMALEAN study, which aimed to assess the effects of semaglutide on the body composition and physical functioning of severely obese patients. Over twelve months, these patients lost significant amounts of weight, of which 22% was lean and 78% was fat. Additionally, people became slightly more hydrated, as water’s share of lean mass increased a bit. You can see the total, fat, and lean mass changes here:

In terms of modifiers, this study fit well within the rest of the literature. Diabetics also lost a bit less weight overall, and a slightly higher share of lean mass (just over 24% for diabetics and just under 23% for non-diabetics). Women also lost a larger percentage of body weight overall, but they lost just under 24% as lean versus 21% as lean for men. People who had previously had bariatric surgery lost significantly more weight than people who had not.

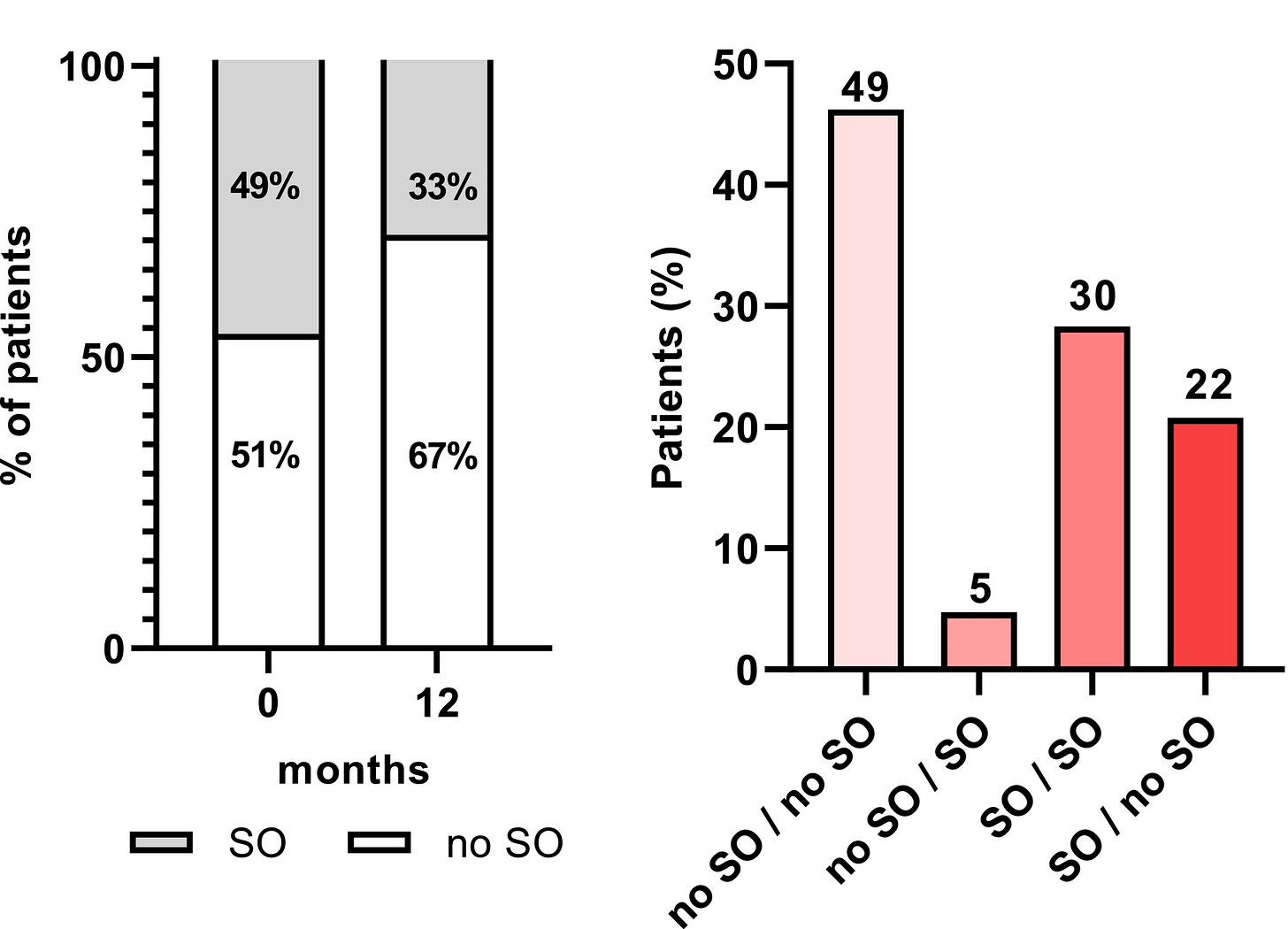

In terms of functional outcomes, handgrip strength significantly increased! In fact, the authors defined sarcopenic obesity (SO) as low muscular function—<27 kg for men and <16 kg for women—and low appendicular skeletal muscle mass as a percentage of bodyweight—<25.7% for men and <19.4% for women—and this improved substantially. That is, sarcopenia became less common after using semaglutide for a year!Overall, the portion with sarcopenia improved from 49% at baseline to just 33% twelve months later. Some 22% who were sarcopenic at baseline were no longer sarcopenic a year later, and 49% of patients maintained their non-sarcopenic status, while just 5% became sarcopenic.

This is a very reassuring set of findings, and it fits well with the rest of the existing literature, although this study lacked a placebo group, making inferences based on it a tad less certain than what we see in some of the other trials. On that note, earlier findings about metabolism being preserved were also replicated. This study found that resting energy expenditures significantly declined by seven months in, by about 244 calories per day. But after twelve months, bodies had adjusted and metabolism was restored, increasing by 140 calories so that it was then minimally changed (dropping about 4.8% overall) despite a much larger decrease in body weight.

In other words, semaglutide reduced body weight substantially, about four-fifths of that weight loss was fat, people became stronger rather than weaker over time (but there was no placebo group), and metabolism was substantially preserved (perhaps explaining how people tend to keep this weight off after treatment cessation).November 17, 2025: Shah and Ayala found much the same that I’ve found above by using mouse models.

First quote: “In both semaglutide-treated and pair-fed mice, once body weights returned to pretreatment levels, lean and fat mass rebounded, and grip strength was restored. This suggests that muscle mass and function can recover as weight is regained.” This is similar to what’s observed in humans undergoing yo-yo weight loss. Outside of some experiments in the elderly, yo-yoing doesn’t seem to lead to more fat than lean mass regain.

Second quote: “[This study] suggests that the loss of muscle function and mass during treatment is not unique to GLP-1RA pharmacology but rather reflects the biology of caloric restriction, and these deficits can be reversed upon weight regain.”December 3, 2025: Ravussin et al. showed that tirzepatide increased fat oxidation while preserving metabolism. Weight loss on these drugs appeared to clearly work as the mainstream suspects: by reducing caloric intake.

As of the latest update on December 3 2025, these results do not change the overall picture generated in the earlier sections of this post.

The most common means of measuring lean body mass is dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, or DXA. When DXA is used, it “sees”:

Bone mineral (minerals in bone)

Fat mass (soft-tissue pixels whose X-ray attenuation matches adipose tissue, like subcutaneous, visceral, or large seams of inter- and intra-muscular fat large enough to dominate a pixel)

Lean soft-tissue mass (everything else, including water, muscle fibers, organs, connective tissue, plus any fat or fibrous tissue interspersed within muscle but too fine-grained for DXA to resolve)

DXA classifies each 1-5mm pixel into one of these categories based on the ratio of low- and high-energy X-ray attenuation. If a pixel contains mostly fat, it lands in the “fat” bin, but small droplets and marbling of fat inside a muscle fiber bundle typically share the pixel with far more water-rich tissue, so the algorithm tags the whole pixel as “lean”. This also applies to fibrous scar tissue and edema in that DXA cannot distinguish them from contractile muscle.

This is known in the literature using DXA.

In studies using DXA in Duchenne Muscle Dystrophy (DMD), we see notes like: “Accumulation of fibrous tissue in boys with DMD can also affect lean body mass measures because DXA does not differentiate between healthy muscle and fibrous tissue and, therefore, measures of functional muscle mass could be overestimated. As DMD progresses, the percentage of total muscle volume decreases as muscle is replaced by fat and fibrous tissue. DXA does not differentiate fat infiltration from intermuscular or subcutaneous fat, and therefore cannot provide a completely accurate interpretation of fat distribution. In some cases, increases in fat mass measures could be a function of background therapy with glucocorticoids rather than a true representation of disease progression.”

Researchers studying adipose tissue depots in HIV patients have noted: “Compared with MRI and CT, DXA cannot separate visceral fat from subcutaneous trunk fat and cannot discern organ fatty infiltration.”

In a tremendous review specifically to compare DXA and MRI body composition measurements cross-sectionally and longitudinally, the authors wrote: “We found that over the relatively short period of 2.5 years, both muscle and lean mass, as measured by MRI, decreased by 4% to 5% in both android and gynoid regions… The apparent lack of change observed by DXA may reflect its inability to differentiate between these compartments.” And, though DXA and MRI tend to agree, “several interventional studies have suggested that compared with MRI and other gold standard methods, DXA is unable to accurately detect longitudinal changes in lean muscle.”

Results tend to speak to a systematic overestimation of lean mass that grows as intramuscular fat rises.

Though this is clinically meaningful in extent and unlikely to purely reflect confounding, I suspect this delta is significantly impacted by residual confounding and that the aging-related nature of so much weight loss in the U.K. Biobank sample explains why their weight loss was so inferior in this sense.

Regarding the mechanistic evidence and the impacts of GLP-1RAs on daily life, we now have genetic evidence that GLP-1 agonism is compositionally beneficial in the general population. A quick-and-dirty MR of my own in the U.K. Biobank indicates that genetically-heightened GLP-1 agonism is significantly related to improved health in many areas. Using the data from that study, we see that genetically-heightened levels of GLP-1 receptor agonism are related to lower weight due to lower fat mass and lower fat-free mass, but the effect on fat mass is relatively greater:

As an aside, these results are such that we can say that some (operative word) number of obese people are obese because they are GLP-1 deficient. As such, GLP-1RAs or other means of stimulating GLP-1 levels could mask their deficiency. This reality invites discussion of what it means to treat conditions like obesity versus “root causes”, as for some, the root cause really is being GLP-1 deficient.

As an aside, the efforts to identify and promote lean mass preserving GLP-1RAs or complementary drugs to be taken alongside GLP-1RAs seem to be efforts to solve a problem that doesn’t exist. This logic applies equally well to efforts to promote exercise and diet alongside GLP-1RAs as, again, there is no real reason to believe there’s a problem. Additionally, it should be noted that because muscle mass is easier to regain than to gain, this problem is rapidly amenable to remedies if it ever turns out to be a real one.

People may have their concerns—as is their right—but they have no legitimate reasons to transform them into worries for others.

The estimated slopes are not affected by removing the numbers for metformin and sitagliptin.

Additionally, if we contrast the reports for Healio and the numbers shown on available conference presentation slides, we can see that combination bimagrumab and semaglutide pharmacotherapy might’ve led to continued weight loss after 24 post-treatment weeks, with the semaglutide-alone groups regaining some weight. Importantly, we do not know if this is a correct inference yet, because the consistency of the estimands for these numbers is unknown. I suspect this possible result is actually due to an error in reporting to Healio, as some of their reported “72-week results” are identical to 48-week results. But some differ, so there’s a question of what’s right.

A bit of carelessness in their reporting might have happened, but that’ll likely be ironed out when the papers eventually drop.

Exercise is independently beneficial, though. Strength training is particularly good for older people to maintain the ability to stand up unassisted, to recover if one starts to fall, etc. I’m not saying one should start juicing at 57, but a few barbells don’t hurt.

Great article, laying out the use, abuse, and outcome of using GLP-1s.

"A pretty apparent fact is that the people who use GLP-1RAs tend to be lazier: they tend to exercise less and eat worse than people losing weight the traditional, non-drug assisted way."

That may or may not be true of those who use them for obesity management, not for people like me who use Ozempic due to being type 2 diabetic.