Brief Notes on Scientific Critique

You actually have to think to do it well

One of the most common article requests I get is for a guide to doing good scientific criticism. I don’t think it’s possible to make a full-fledged guide—the topic is just too expansive—but I do think I can provide some helpful tips for comporting yourself. As a bonus, those tips will also give curious people more insight into how I think about this topic, because a lot of this is going to be my opinions.

Scientific Criticisms Should Be…

The first and most important thing a scientific criticism should be is correct. If you’ve read a paper and you think you’ve found a fault, you have a duty to yourself and to others to identify if that fault is real before voicing your criticism. Just ensuring that would eliminate virtually all lay scientific criticisms that are ever voiced in the public square. This speaks to how bad most criticisms are: it speaks to the fact that criticisms are generally not correct, and frequently Not Even Wrong.

A related heuristic is Henderson’s First Law of Econometrics. It’s a tongue-in-cheek ‘law’ that reads:

When you read an econometric study done after 2005, the probability that the researcher has failed to take account of an objection that a non-economist will think of is close to zero.

This point is not literally true, but it is directionally true. People want to get ahead of criticisms of their work and researchers tend to be smart people who can think up most of the critical flaws that are worth getting ahead of. Accordingly, the bar for a criticism to be correct is going to be higher than lay people are used to because they’re just not accustomed to people being circumspect. This is a major part of why simply being correct that there even is something to criticize can1 be such a high bar.

A big part of ‘coming correct’ with scientific criticism is checking yourself when you can. You can’t always definitively know if a criticism is correct—sometimes there’s just not enough information available. When that’s the case, you need to go far as far as you can, establishing that something is ostensibly correct based on all the available facts. But in some cases, you can go all the way, because there’s plenty of information available, and if you fail to do that, then you might be making a fraudulent critique.2

I’ve noted several dozen instances of this in the past. One of them became an article, which you can go read here. I’ll use that article to explain this concept.

Here’s the gist: Eric Turkheimer and his then-graduate student Evan Giangrande decided to critique some empirical work that clearly made them extremely upset, but they committed fraud to do so. The nature of the fraud is that these men had every tool and bit of required data available to them to check if several—and, indeed, when it comes to criticisms that could be important, all—of their criticisms were correct, but they did not. They simply made their critiques without checking for correctness. As it turns out, they were incorrect on all counts. They committed fraud because they should have known better and they are competent enough to know better. They had every opportunity to avoid levying incorrect criticism, and they elected not to. Instead, they proved they can never be trusted again.

Another major criteria for good scientific criticism is meaningfulness. I feel like this is good to mention right after correctness because of the example I just used. Turkheimer and Giangrande engaged in a form of criticism that’s known in their field as “pseudo-analysis”. Thomas Bouchard gave the name to this form of criticism decades ago in a volume that contained a lot of debate between the field’s guiding lights. The problem was named, but it didn’t go away.

The idea behind pseudo-analysis is to come forth with a bunch of potential problems for a paper, design, result, whatever, without showing that they’re real problems. When you’ve tallied up enough possible issues, you then declare victory.3

Even if not one of the criticisms has any merit, readers might wind up convinced that there actually are major issues and that the work is worthless. They might even become convinced that the people being critiqued have bad character—after all, why would they miss so many problems? How could a person with integrity be so wrong?

But pseudo-analytic critique is not meaningful. The highlighted issues usually have no value because they don’t affect the results being critiqued.4 You can say ‘What if the result is confounded by X?’ and while this might feel like a critique, it’s not, it’s just an empty assertion, and it’s also not meaningful without showing that X can matter. Unfortunately, if it turns out X does not matter, the pseudo-critic usually doesn’t drop the issue, because meaningfulness is not something that matters to them.

Sometimes criticisms are so empty that, even if they’re entirely correct, the maximum change they could elicit in the results is still nearly nothing. Sometimes they’re even correct, but the effect on the results is directionally backwards, and if the critique is accepted, the results become stronger in a way the critic might not have expected! If you want to do critique well, try to figure out if your lines of attack matter, and only focus on the ones that can. That might mean putting in work at quantifying the strength of a potential confounder or the sensitivity of a set of results to measurement error, or any other of a number of things, but it always means you have to think.

Criticism ought to also be relevant. This has to do with your relationship with the thing you’re critiquing. A criticism can be irrelevant for many reasons, not least of which is that you’re focused on something that isn’t germane to the authors’ points. If your aim is to take on the conclusions made by some authors, you need to attack those points.5 But criticisms often have nothing to do with the points made by the authors.

If you’re going to critique something in a paper aside from the main points of the authors, that is completely fine. But you need to be explicit about doing that. If you cannot focus on the right things, or even say what you’re focused on, then why are you attempting to engage in critique in the first place? It takes very little effort to get to the point, so you should. Just as well, however, it’s important to try to understand where a critique is coming from if you’re on the other end. Sometimes someone is making a benign observation; reacting too harshly isn’t conducive to discussion.

A similar criteria for good criticism is that it should be contextualized whenever appropriate. One of the most common poorly contextualized criticisms that I see is that a given effect size is small. But what is a small effect size? There is no objective criteria for determining that an effect is small, much less ignorable, so the way we arrive at that conclusion is to establish some sort of baseline to compare against.

To explain what I mean, I’ve used examples like pygmy height and social media effects, among many other things. In the pygmy example, I noted that for genetics to fully explain why they’re so much shorter than their neighbors, the correlation between admixture and height would need to be a ‘mere’ 0.34. To some, this is unacceptably low, but in this context, it explains 100% of a very visible group difference! Likewise, I noted that all it would take to raise the diagnosed or diagnosable depression rate by about 50% from a given baseline would be a ‘small’, 0.16 correlation between social media use and depression.

A related example where context is required, but frequently absent, is complaints about statistical power. There is no such thing as ‘low power’ in any objective sense. Power is always a function of the features of the thing being studied, so if your goal is to show that something exists, providing one example is enough. A study with an n of 1 has just enough power for that! An n of 200 could be a huge study when it comes to studying a group difference of 1 d or it could be a pitifully small study when it comes to determining if the latest cancer drug leads to improved overall survival over a year.

Getting context right requires both statistical and theoretical thinking. I’m going to use power analysis as an example for this, but try to think more broadly than that.

You have to develop some level of domain expertise to determine that there’s low power—even if it’s just the amount you’d get from a five-second Google search—because you won’t know a priori what effect size is realistic or important for some domain unless you’re already an expert in it. You also need to know what type of power analysis to set up. The functional form of the relationships being questioned affects the results. You may have lots of power to detect a group difference, d, but little to detect a relationship, r.

Criticism also ought to be kind. If you’re not able to be generous, then you mustn’t criticize. People who do not abide by the principle of charity when engaging in critique frequently generate irrelevant criticisms, and I personally find it hard to imagine a world in which they engage substantively while doing so without charity.

One of the most common ways the need for charity rears its head has to do with misinterpreting people’s statements. Someone might say one thing and then an uncharitable person will come along and interpret it a way that doesn’t match the authors’ intent at all. The author has no obligation to defend such an interpretation, but the fact that the faux-criticism has been voiced might force them to go on the defensive because otherwise they’d have to deal with the blowback from people thinking—wrongly—that they said what they’re being criticized for.

Another common way the lack of generosity shows itself is when people don’t appropriately interact with authors. For example, someone might have put up a preprint and they might have made an error that still has time to be corrected. In that case, it’s better to contact the author directly—privately. (This is easily ~99% of my interactions with researchers. I even frequently praise or post about something they found while privately contacting them to address other errors, strengthen certain results, correct tables or text, test alternative explanations, etc.) Similarly, if someone is showing off a simulation, has made a blogpost, or in some other place done some analysis that includes a potentially impermanent mistake that they have room to correct, go to them. If you can’t do that, then you’re poisoning the commons and encouraging extreme reactions to criticism and extreme reluctance to produce knowledge. You are being anti-humanist and you’re militating against progress.6

To be generous means to act in good faith, and that has to dot all of your interactions. You have to ask people for clarification and assume good faith in them until they’ve demonstrated otherwise. You have to take people at their word until they’ve abrogated it. You have to do little acts of kindness that might not be reciprocated. And, unfortunately, if you’re a normal person, that will feel bad because everyone won’t stick to the same high standard. I’m sorry, but you just have to live with it.

Good Criticism Is Not Routine

There are no ‘general-purpose’ criticisms. No legitimate problems apply to all studies, so there’s no way to get to good critique through rote memorization and repetition. You cannot be a credible critic with criticisms amounting to repeating lines like…

‘It’s a meta-analysis. Those are all bad.’

‘That study was small. Next!’

‘Correlation not causation.’

‘Ever heard of the replication crisis?’

‘A 0.4 correlation is too small to matter.’

‘Those authors worked for [company]. We can ignore what they have to say.’

Five of these can be good criticisms given the right context, but it is incumbent on you as a critic to supply that context.7 For example, just saying that meta-analyses are bad is not sufficient to critique a given meta-analysis. Because meta-analyses are not inherently bad, you will need to go the extra distance and explain specific faults. Likewise, you need to able to justify the claim that a study is small. You should be able to answer questions like ‘Small for what?’ And you should also be able to explain why a given conflict of interest is actually one—having received a study grant for Pfizer doesn’t make someone a shill for Diet Coke!

I suspect that simple, rote criticisms actually make the public less capable of engaging in any sort of scientific critique. It is too easy to regurgitate a simple criticism that sounds scientific but actually lacks substance, so there’s a sort of Gresham’s law that comes into play. Since the substance in a critique always comes from the specifics of the case, just avoid rote criticisms and one-liners; keep your mouth shut if you’re unwilling to put in the effort to do a good job.

But, just because you should avoid repetitious lines does not mean that there aren’t plenty of good and simple heuristics for critique. For example, a small sample size can be a clue that a result is unreliable. It’s not definitive and you still have to justify that a given sample size is small, but it can nonetheless be a stepping stone to substantive critique.

One useful heuristic I’ve pointed out is when there’s an excess of p-values in an article that are just significant—meaning that they’re right below the significance threshold—that makes a result suspect. Another is that authors talk about interaction tests—a difference in a coefficient between groups—without actually running the test. This is such a frequent issue that there are many articles in different fields about exactly this problem. My favorite comes from neuroscience, but the definitive article on the case is Andy Gelman’s.

In any case, you cannot apply these heuristics blindly. If the p-values are suspicious, show it; if the interactions aren’t tested show it if it matters; for any other heuristics you may want to apply… think and justify!

Noticing!

Let’s walk through some examples of bad science critiqued fairly. The idea here is to help you to think about how you would notice errors in studies. I’ll mostly reference my own writing for this. I’m going to start with gas stoves based on an article from before I started an account on Twitter/X. If you haven’t seen it, you can find it here:

The major claim made by the paper is that gas stoves are responsible for more than 10% of childhood asthma cases in the U.S. The authors reached this conclusion by calculating the Population Attributable Fraction (PAF) of asthma cases with an effect size scrounged up from a meta-analysis. That meta-analysis, as it turns out, was poorly done, and correcting its numerous errors reduced the amount of asthma attributable to gas stoves by more than half. That meta-analysis was also superseded by a study that was larger than the entire literature up to that point, and that study found no effect whatsoever, resulting in a PAF of zero.

That explains the majority of the substance of my critique of the paper. But I also brought up that the effect sizes are not from causally-informative studies—meaning that causal inference is tenuous and the results should only be acted on only with an extreme of caution—and that the authors had a notable conflict of interest with regards to their conclusions. This isn’t like saying that a person had a conflict of interest because they once received a grant from Pfizer and now they’re writing about the unrelated benefits of aspartame, it’s saying that these people have a specific conflict of interest because they work for a company that’s committed to retrofitting buildings to ensure they don’t have gas stoves—the very thing they were attacking! This isn’t totally damning, since people with conflicts of interests can be working on their topics of interest because they really believe in what they’re doing, but it definitely looks worse when you notice that the authors failed to declare that this was a conflict of interest at all.8

You only notice these sorts of issues by actually reading. There’s no canned way to end up finding all of this.

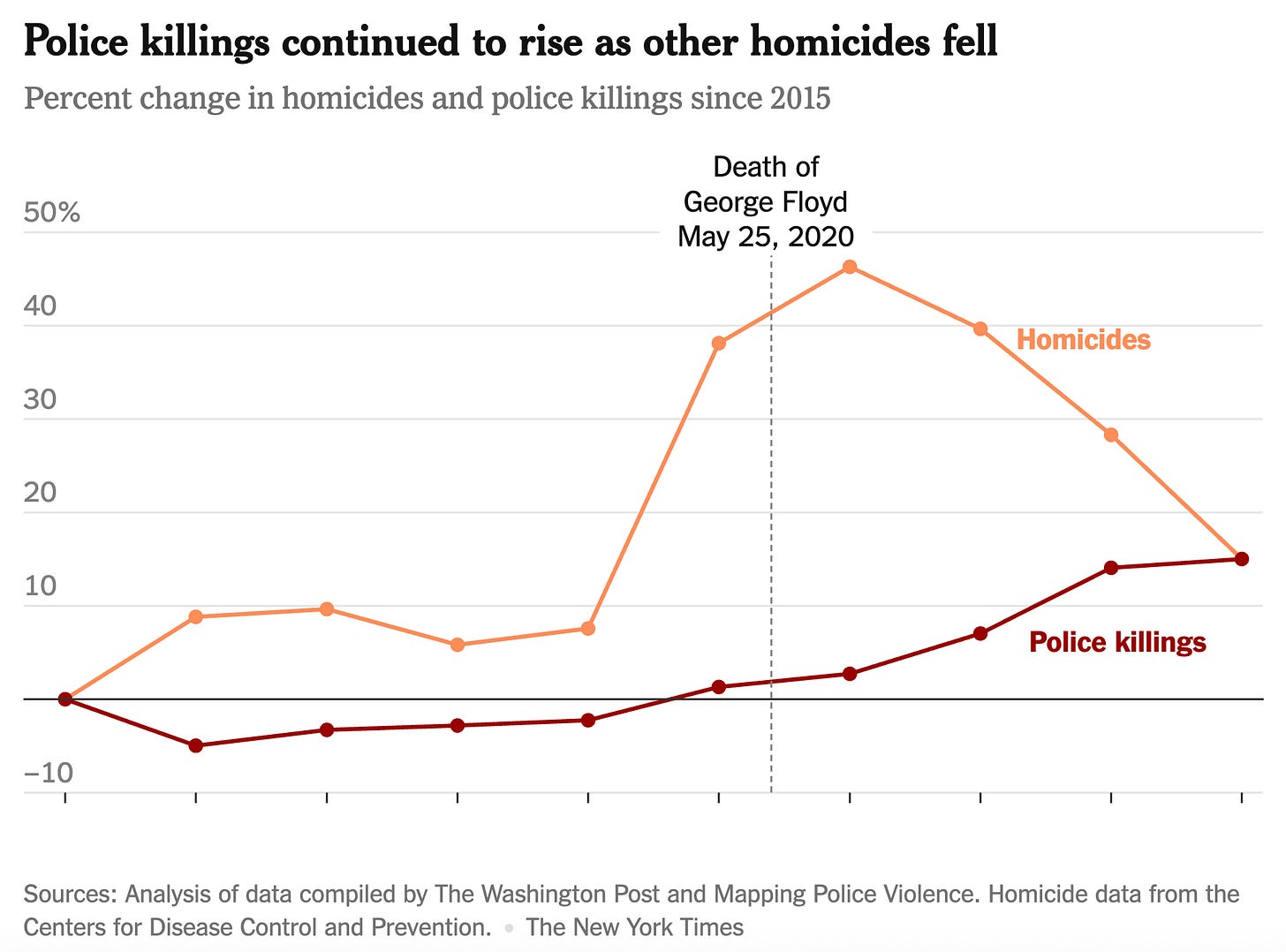

Here’s a figure from the New York Times. Can you tell what’s wrong with it?

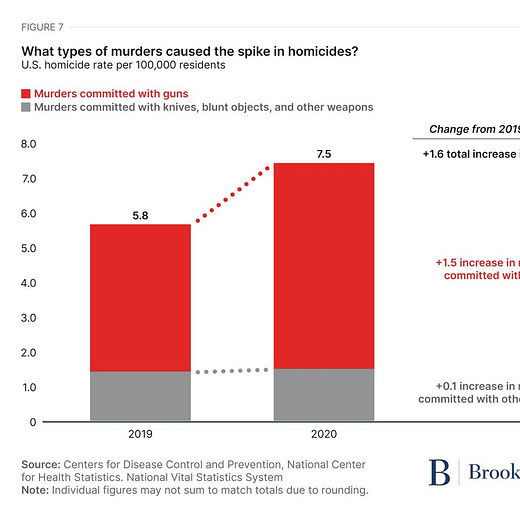

The issue here is that it looks like the rise in homicides happened when 2020 started, rather than during 2020. This is entirely due to the annual-level aggregation the authors chose. As it happens, the rise occurred on the day George Floyd died—hence why the rise in homicides has come to be known as the “Floyd effect.” But because all of 2020 is bundled together in the NYT’s chart, it appears as though Floyd’s death was irrelevant. This is a very misleading chart, and the sort of error that should be noticed and pointed out, even though astute readers shouldn’t be fooled by it. The reason this should be pointed out has to do with the fact that astute readers also can’t be informed by it: they cannot help but notice that the Floyd line is uninformative, but they also can’t be informed about the timing of the homicide hike within 2020. It is a chart that will mislead many, and it can’t inform people who it doesn’t fool either! That it puts police killings (rare) and homicides (less rare) on the same scale doesn’t help and might be notable, but isn’t a crucial weakness, so I wouldn’t critique that aspect.

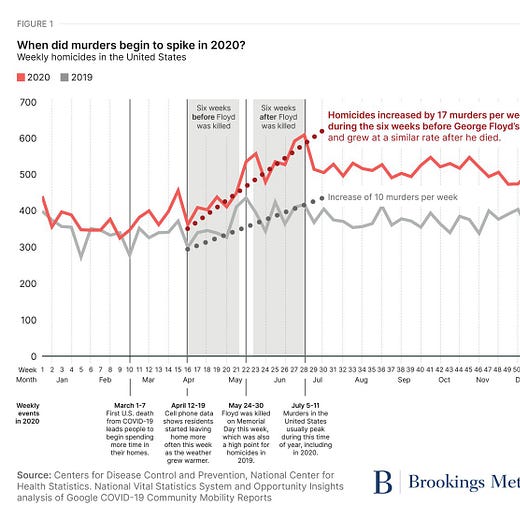

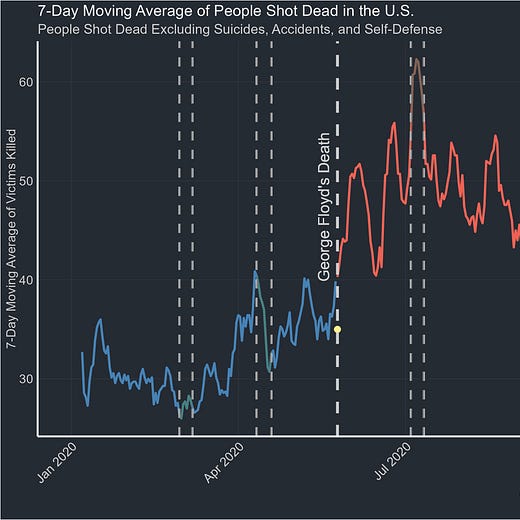

On the subject of the Floyd effect, many have engaged in valiant attempts to deny that it had anything to do with George Floyd’s death—to deny that there’s even a Floyd effect to speak of! The most popular example came from Brookings, and it was embarrassingly bad and worth of retraction.

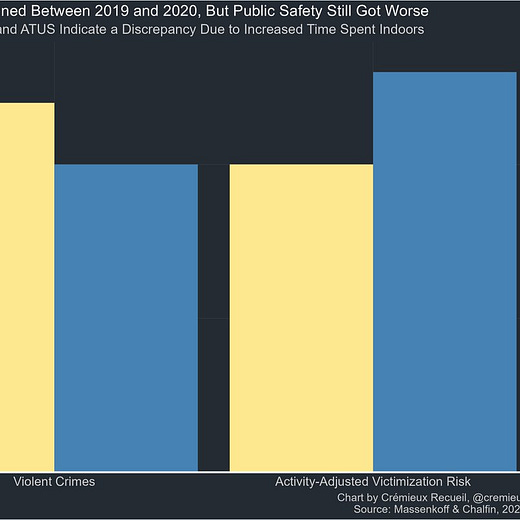

The nature of the argument in Brookings is that the Floyd effect was actually just going to happen anyway due to COVID lockdowns and typical seasonality. But the authors didn’t notice that such a thing occurred only in America, only among Blacks, not in any way related to lockdown timing, and that the seasonality their argument relied on did not, in fact, exist in data from any year in the preceding decade. Moreover, when you drop down to a lower level of timing granularity—that is, you go from weekly to daily data—their argument totally falls apart because their claimed timings aren’t replicated. The Brookings piece also tried to explain away the U.S.-specificity of the homicide hike by arguing that there was something to do with America’s guns, but this argument falls apart when the broader increase in non-gun violence adjusted for time outside is noted.

Their argument was a farce and clearly based on elaborate cherrypicking of the sort most readers would not notice without a lot of prior information.

Speaking of Brookings, they have published many errant reports. Another that I’ve critiqued before was on laptop versus longhand note taking. To be fair to Brookings, they weren’t alone in picking up these results, nor were they alone in their credulity.

The essence of the issue here is that the attack on laptop-based note taking is based on obvious untested interactions. The interactions were so obvious that the authors of the papers knew to test them, but didn’t when it wasn’t convenient. Additionally, they likely engaged in p-hacking, as evidenced by the incredible excess of p-values that were dubious and the fact that such an excess did not show up for the tests they needed to, but did not run. Then, to top it all off, the result didn’t replicate.

One of the worst meta-analyses I’ve seen in recent years helped to popularize the statistically unreliable result that dancing was among the most effective treatments for depression. At the time, I thought it should be retracted. Now, I still do.

This meta-analysis had practically everything wrong with it: low power, results driven by poor quality studies, citations to fraudulent and nonexistent studies, and, ultimately, the result can’t even be recovered. Due to the design of the study, the different interventions cannot be credibly compared—a problem that excludes most arm-based meta-analyses from being valid! The samples, designs, and measurements just differ far too much, and there’s lots of evidence of incomparability in different places throughout the study. It’s just shot-through, and obviously so if you dig in at all, but it still became immensely popular in the meantime.

One of the most annoying studies I’ve come into contact with was one that news outlets ate up for inexplicable reasons. Its authors claimed that the rooms test-takers took tests in had an impact on their scores: rooms with high ceilings resulted in lower performance! But, if you read the study for event a moment, you’ll notice that conclusion is the opposite of what they found. The authors ignored their own result!

I’ve produced a public record including critiques of over a thousand studies across dozens of fields from psychology to physics. All of those critiques have been substantive and have noted real issues that matter, in no small part because I won’t put anything out there that doesn’t matter. I also tend to ignore studies as targets for critique if I notice others have already dissected them, if they’re totally inconsequential, or if I think it’s better to provide elaboration to build off of them instead.

In the time I’ve produced those critiques, I’ve learned that there really is no alternative to simply knowing the area for the would-be critic. For example, some researchers detected massive amounts of fraud because they observed that images generated by scanning electron microscopes were mislabeled. Most people don’t know the first thing about microscope models, so they’d never be the wiser!

So, how do you notice more errors? I suspect the answer is mostly about a combination of actually reading things, getting more experience noticing these things, and thinking through if you should say anything at all.

As an example of the last thing, say someone says human growth hormone helps to make children taller and someone objects that Lionel Messi used it and he’s still short. That objection might feel right in the moment, but it’s obviously nonsensical because a likely counterfactual is a world in which Messi is somewhat shorter than he is because he didn’t take growth hormone. Simply recognizing that intuitive remarks like that need to be inspected and thought about is itself an aid to noticing errors.

If I had to summarize my thoughts on scientific critique9 I would say this:

You have to try your best to be correct, you have to be generous, you have to keep criticisms relevant, and you should only critique what matters, when it matters. You also have to try to know specific things so that you can recognize when specific other things are ‘off’, and you have to learn to know when you don’t know something so you can ask questions instead of providing comments. You’ll also need to avoid the temptation of rote criticism. If you do all of that, you can provide something valuable to the world. If you can’t do all of that, then, frankly, I think you shouldn’t even try.

“Can” is an obviously key word. Key words are important and part of ‘coming correct’. Oftentimes, people will read something a researcher has said as if it’s false, when the researcher actually used a key word that makes their statements, findings, or whatever else technically correct. If your criticism amounts to ignoring that sort of key word, then you have not come correct.

I am also partial to the view that lying about a person, events, results, or whatever in ways you cannot justify is a form of fraud. Even if you can do that in theory, then stand down if you aren’t prepared when you make the claims, or you’ll quickly find yourself telling lies out of a lack of preparedness.

This is very common among academics trying to establish consensus against people (the essence of ‘cancel culture’). Sometimes, you can even catch them proving to themselves that they’re doing this (here’s a recent example), but good luck convincing them that what they’re doing is wrong.

Similar to the Gish gallop.

Here’s another contemporary example, that really might not be applicably called contemporary because it’s about decades-old, already-addressed complaints.

A very lazy but unfortunately common way of doing this is to attack an authors’ choice of range on a graph the author produced. There is no objectively correct way to display data, so this line of attack is always about matters of opinion and is therefore scientifically fruitless.

In other words, when engaging in critique, you ought to think about the commons!

#4 is the odd one out.

Another example of conflicts of interest that matter comes from the growth mindset literature. In that literature, we can see that conflicts of interest that have to do with growth mindset (i.e., directly relevant ones) do actually materially impact the nature of reported results: authors with financial conflicts of interest report large, positive effects, and those without them find nothing!

Scientific critique, as distinct from ethical critique, like that applied to studies that are conducted in an unethical manner, include plagiarism or AI-generated text, involve stealing analyses or ideas, or suggesting harm to others, etc.

Regarding scientific research, I think that a helpful starting point is knowing that most of it is wrong, and that a lot of lay beliefs about science (e.g. trauma, mouse utopia, climate) are too. Knowing that and internalising it is the first step. The second is figuring out what can be known at all beyond that, which is ultimately a philosophical question. Personally, I gravitate towards appearance > reality and that there is no truth, but perspective.

Helpful resources, from most to least:

replication crisis -- https://gwern.net/replication

regression to the mean fallacies --https://gwern.net/doc/statistics/bayes/regression-to-mean/index

made up statistics are worth it -- https://slatestarcodex.com/2013/05/02/if-its-worth-doing-its-worth-doing-with-made-up-statistics/

convenience samples work --https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1808083115

comments on statistical fudging -- https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/01/02/two-dark-side-statistics-papers/

examples of criticism of scientific researchhttps://gwern.net/research-criticism

problems with scientific research -- https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/04/28/the-control-group-is-out-of-control/

isolated demands for rigror -- https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/08/14/beware-isolated-demands-for-rigor/

correlation is common -- https://gwern.net/everything

Philosophy:

Beyond Good and Evil

Twilight of the Idols

Best Nietzsche youtuber: https://www.youtube.com/@untimelyreflections