Schooling Effects Beyond Test Scores

The benefits of education aren't necessarily mediated by cognitive improvements

This is the fourth in a series of timed posts. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. Check out previous examples here, here, and here.

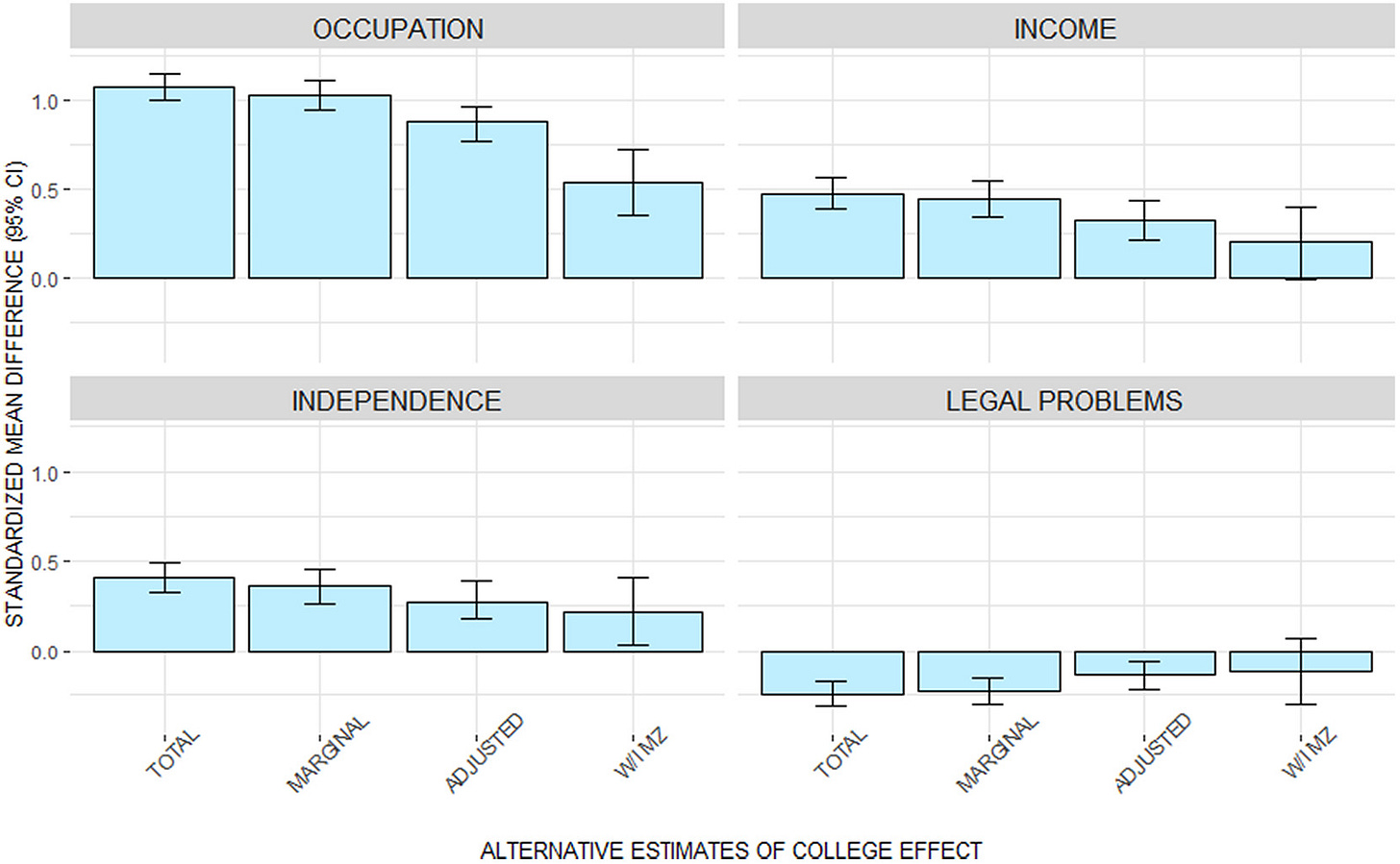

In a previous post, I remarked that a longitudinal evaluation of Vietnam war-era males found that “the income-boosting effect of education wasn’t mediated by boosting test scores, it was separate from that effect.” In another study, McGue et al. found much the same: controlling for intelligence, personality, education polygenic scores, and family socioeconomic status, educational attainment retains some association with higher socioeconomic status.

The association of education and some dimensions of success even works out within pairs of identical twins controlled for intelligence and personality:

For many people, this is remarkably unintuitive. It’s common to believe that the benefits of education and educational interventions are down to cognitive improvements that show up in test scores and that, if test scores changed, the improvements that led to those changes mediated other benefits that followed particular educational interventions or experiences.

I’ve never held this belief for one simple reason: the effects of educational interventions on test scores generally aren’t “real.” Many things increase scores, but the most most common reason for score increases is test bias, followed by very narrow skill improvements.

There aren’t many reasons why test bias should have predictive validity. Briefly, if a test becomes biased, that means that individuals whom the bias favors (disfavors) perform better (worse) than expected given their true ability level. One scenario that comes to mind where bias could be helpful is one in which the reason for the bias is the acquisition of a specific, job-relevant skill that’s assessed on a test, or some permutation of that scenario.1

There’s not much reason to think that narrow skill improvements will have much predictive power either. The sorts of skills required to do well on a test are just not usually the sorts of things that allow you to do better in the real world. It’s not surprising, then, that when people look at which aspects of tests predict things, they generally find that specific skills have limited predictive validity net of g.

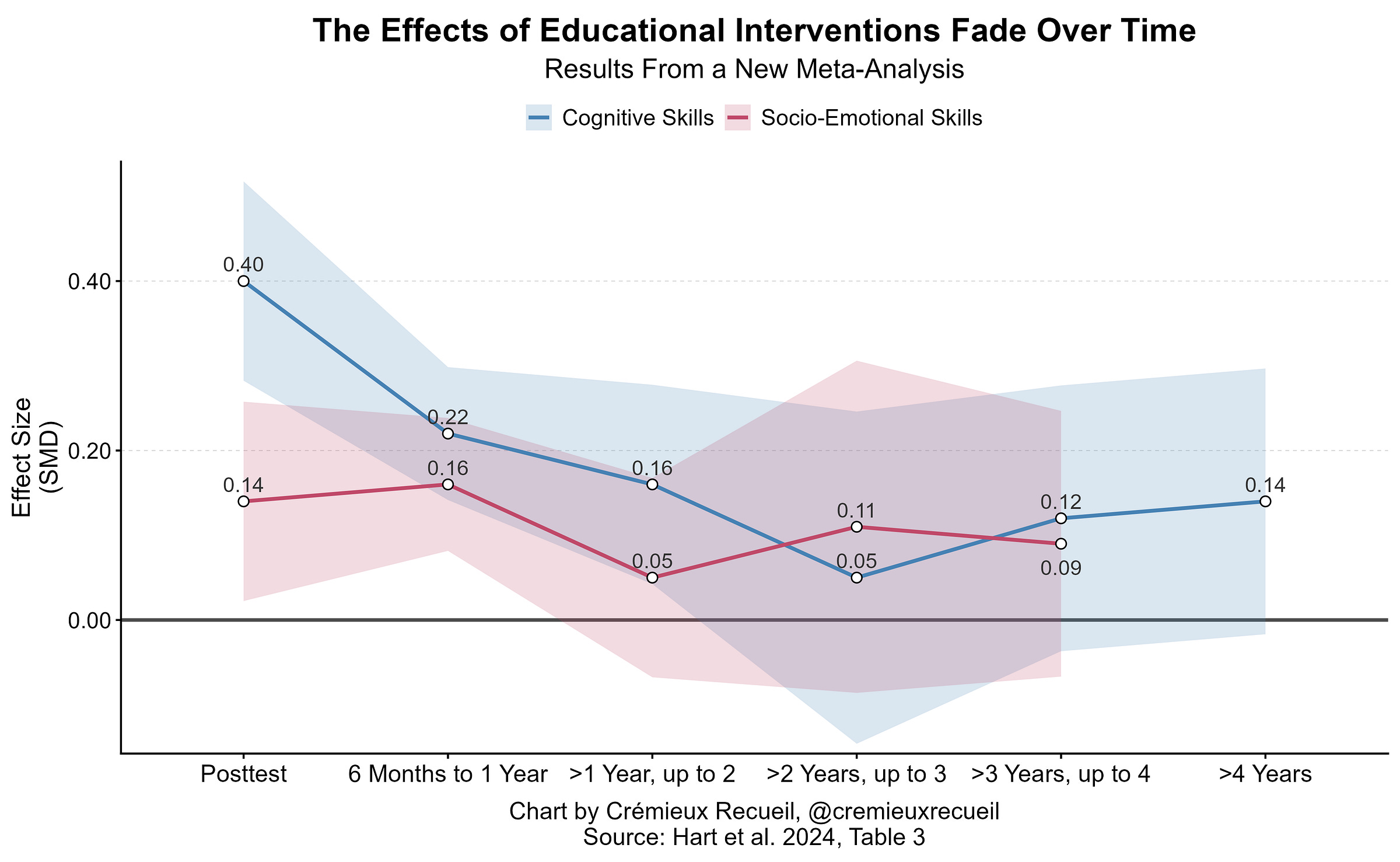

A final major knock against the practical significance of test score improvements is that they tend to fade out over time.

A primarily biasing, generally narrow, and transitory test score improvement does not sound particularly helpful.

Despite weak theoretical foundations for why we should value test score improvements on their own, people still do. Maybe they want people to get higher scores so they can pass hurdles like mandatory end of course exams or so that they can reach hiring criteria for test score-gated jobs. Or perhaps they really think that improved scores imply people have gotten smarter and thus they expect the improvements to predict the downstream things differences in test scores do in the general population. If they believe the latter of those things, then they’re wrongheaded, and we don’t need to look at psychometric research to see why.

Why Do Quality Schools Matter?

Meta-analyzing the test score benefits of public secondary schools estimated by admission lottery and score cutoff studies, we see that they don’t really do much for test scores, whether they’re preferred schools or they’re simply elite.

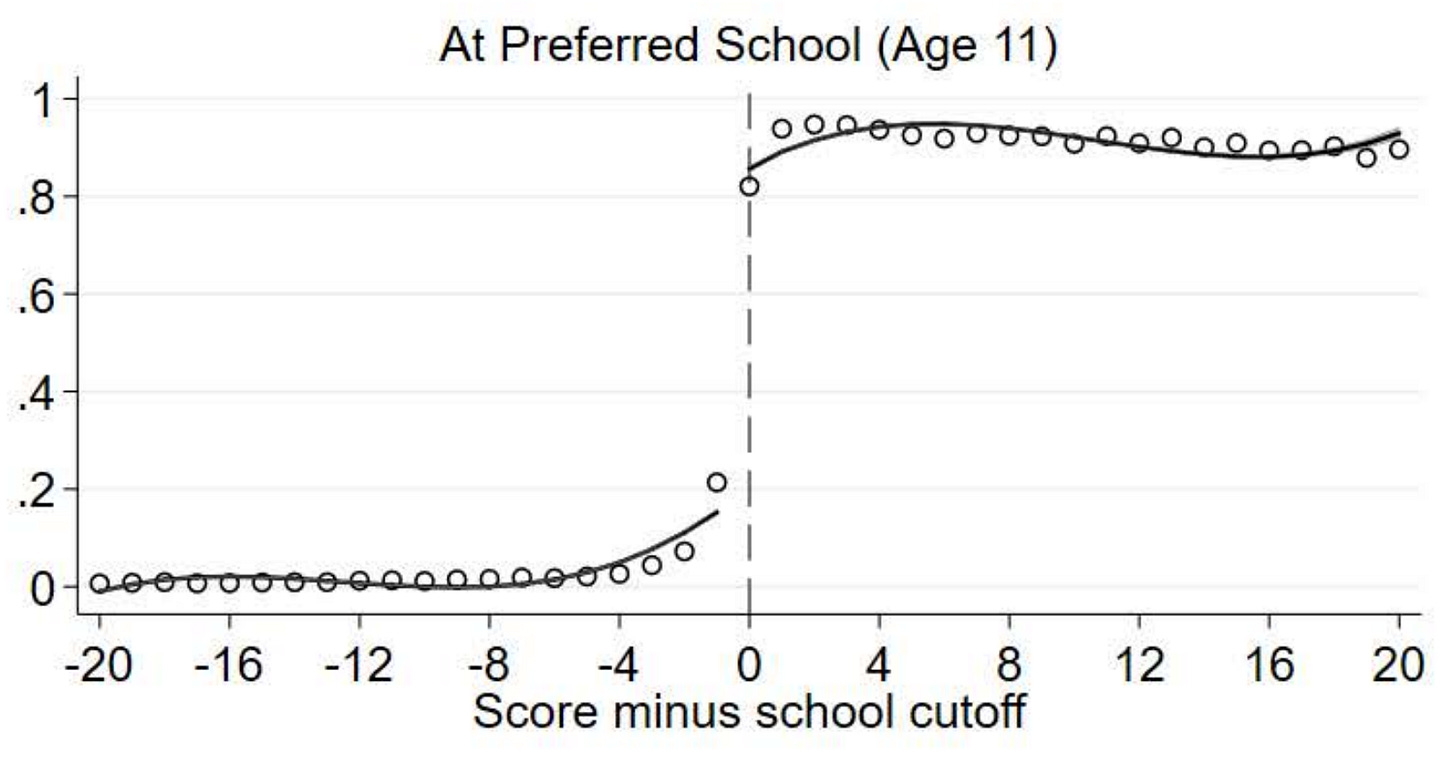

At the end of primary school, Barbadian students sit the Barbados Secondary School Entrance Examination, or BSSEE. When they sit the exam, they also submit a list of secondary schools they’d like to attend, and each school is assigned a test score cut-off for entrance. Crack the cutoff, get into the school you wish to attend. Those who are right at the cutoff are plausibly no different in skill than those below, making this a good design to see how well-matched students perform when the difference is just getting to attend their preferred schools.

To show the design works, almost every kid who reached the test score cutoff went to the school they wanted to go to.

Preferred schools are better off in many respects. Going to a preferred school is causally associated with having “higher-achieving peers, more academically homogeneous peers, and smaller cohorts”, but despite the peer and teacher benefits, going to that preferred school doesn’t seem to matter for later test scores.

Secondary school exam pass rates might not be enhanced, but preferred school attendance is associated with certain aspects of educational attainment. Students attending their preferred schools go on to take more of the elective Caribbean Advanced Proficiency Examinations (CAPEs) needed to carry on with tertiary education domestically. If students pass seven CAPE units, they get a CAPE Associate’s Degree, and the kids who narrowly made it into their preferred schools went after more of them.

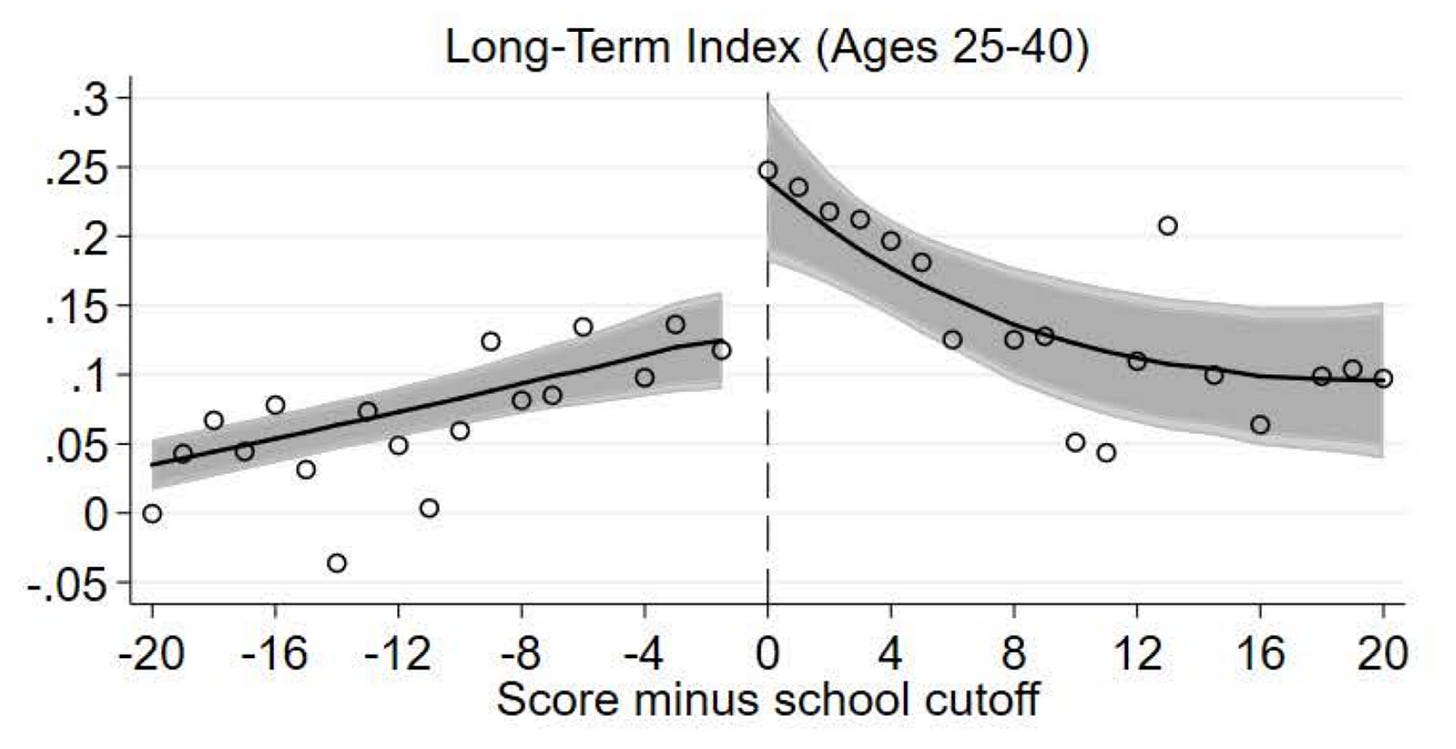

There’s additional evidence that preferred school attendance helps other outcomes in the form of effects on a “long-term index” of said outcomes. This result looks visually convincing at the threshold, but it takes on a baffling form thereafter and unlike with the CAPE Associate’s Degrees, I can’t think of a good reason why.

The long-term index is composed of measures of educational attainment, occupational status, wages, and health behaviors and outcomes and, on inspection, it seems the only robust, non-marginal effects were on the health part. Specifically, preferred school attendance was related to going to the gym on a weekly basis and being a normal weight rather than being obese.

These long-term impacts aren’t huge, they aren’t pervasive, and they might not be the most impressive things out there, but they could be something, and they’re impacted despite the much better evidence for no effects on test scores in the sample. The fact that at least one form of educational attainment (CAPE Associate’s) was clearly impacted speaks to at least some form of test score-independent impact on a valued outcome due to improved school quality—it speaks to multidimensional schooling effects.

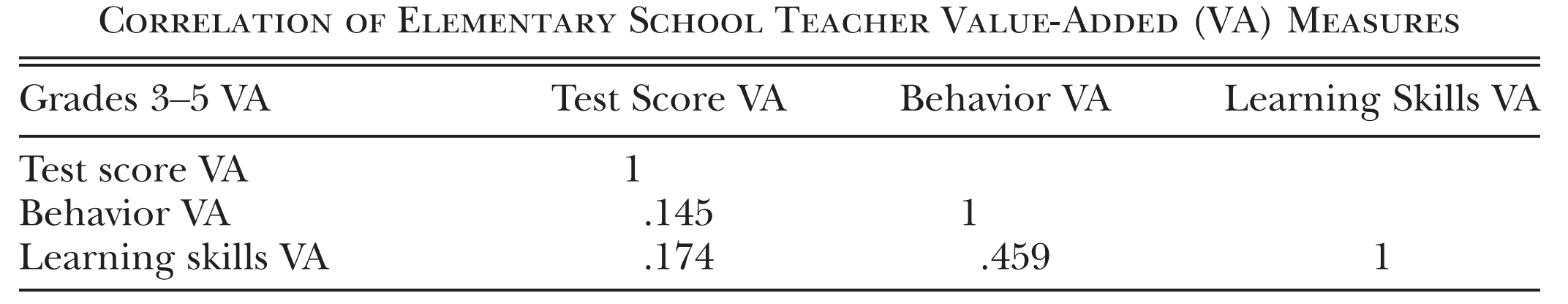

Using data from the Los Angeles Unified School District, Petek and Pope produced some pretty standard estimations of teacher’s value-added to students.2 The twist is that they deviated from common practice since the 1970s: they looked at test scores and other outcomes. The other outcomes beyond student mathematics and English test scores were a composite behavioral index (GPAs, suspensions, absences, being held back) and a learning skills index (effort GPA, work and study habits GPA, and learning and social skills GPA).3

For the third- to fifth-grade students in the study, the indices were substantially, but not spectacularly intercorrelated.

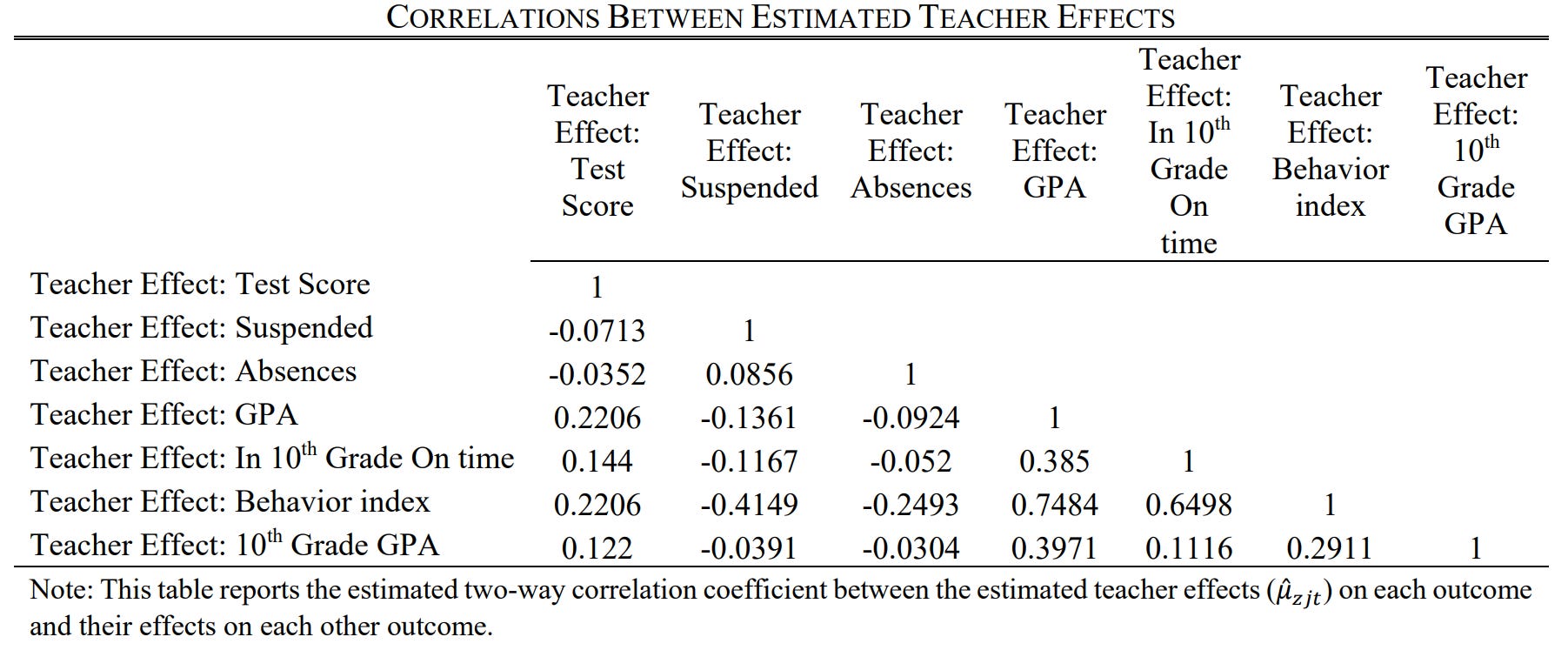

But on the other hand, teacher value-added to the different measures was much further from being highly intercorrelated.

The value-adds by teachers for test scores and the other composites were overwhelmingly independent. That’s somewhat shocking since it’s hard to imagine an environment that fosters higher test scores but doesn’t also foster noncognitive skills and improvements to some of the independently valuable outcomes in the other indices.

That result was based on very large data, so for many purposes, it’s probably good enough. But lucky for us, it also replicates. Using data from every public school attending-ninth grader in North Carolina between 2005 and 2012, Jackson arrived at a substantially similar result.

This exercise was repeated two years later by Jackson et al. with data from high schoolers attending Chicago’s public schools. The independence of the dimensions of value-added isn’t what I want to focus on with this study.4 What I want to focus on is the predictive power of the other dimensions versus the test score one. In this case, the dimensions I’m referring to beyond test score value-added are social value-added (a measure of interpersonal skills and school connectedness) and hard work value-added (a measure of academic effort, perseverative attitudes, and academic engagement).

For predicting high school graduation and immediate four-year college enrollment, those dimensions of school-level value-added outperformed the test score dimension5

But the buck doesn’t stop there. The same result shows up for ever receiving a school-based arrest, which is a very substantial outcome that impacts life down the line in obvious ways. That outcome may be more confounded with the sources of school-level hard work and social value-added, but it’s still worth mentioning. A big reason why it’s so worth mentioning comes from a later publication that used this data again for a series of heterogeneity analyses. That publication showed suggestive evidence that—at least for some outcomes, including school-based arrest—less-educationally advantaged students benefit more from non-test score school value-added.

All of this is to say, schools and teachers provide multidimensional value-add that goes beyond effects on test scores alone, and this value-add matters. Some estimates are dubious, and most are small, but so are the effects on test scores, so if you value those, you should value both.

Parents do value both, which dissolves a common argument about parental school choices. Because it has been standard for so long to conceptualize school and teacher value-added in terms of effects on test scores, it has also come to be assumed that when parents select schools and leave test score value-added on the table, they’re showcasing choice inefficiency. For one, there’s lots of evidence that parents are responsive to that sort of academic quality, albeit very imperfectly.6 For two, as we just saw, there’s more than test scores to consider.7

Evidence that parents do consider those dimensions has recently become available.

Using data from Trinidad and Tobago, Beuermann et al. found that schools contributed to test scores, but also to teen motherhood, and both participation in the labor market and crime. Because there’s sufficient relevant exogenous variance in school assignment and parents provided lists of the schools they wanted their kids to attend, this analysis ends up being a causal one where choice can be meaningfully inferred and broken down.

[Parents] choose schools that have larger impacts on high-stakes tests and also those that decrease crime and increase labour market participation. These patterns persist even conditional on average school outcomes and peer quality. These results suggest parents may use reasonable measures of school quality when making investment decisions for their children—a requirement for the potential benefits of school choice. The fact that parents do not only choose schools that improve academics but also those that improve non-academic and longer-run outcomes suggests that the benefits to school choice may extend to a wide range of outcomes (not just test scores).

In other words, the multidimensionality of school impacts does seem to be met by the multidimensionality of parental choice.

High-achieving students’ choices are more strongly related to schools’ estimated impacts on high-stakes exams than on non-academic outcomes, while the choices of low-achieving students are more strongly related to schools’ impacts on non-academic outcomes than those on high-stakes exams.

Pity the Poor Teacher

We misevaluate teachers, schools, and interventions when we focus too much on test scores. We misevaluate interventions specifically when we attribute their positive impacts to what they’ve done (or not done in altogether too many cases) to student test scores. But most of all, we create bad policy when all we care about is test scores.

No Child Left Behind and its numerous incarnations, like Britain’s League Tables, are policy catastrophes. They were ideas predicated on the view that schools that raise test scores are the best schools, full-stop. But because school quality is multidimensional, we know that won’t always be the case. It may be the case on average because, as we did see, positive dimensions of school quality are correlated. But in some cases, the best school for a given group of students—say, low-achieving ones—might be the school that’s far from the top in terms of test score value-added. Those kids might benefit more—end up with higher wages, avoid prisons and gangs, go to college, etc.—from a school that ranks high on other, neglected dimensions. It might even be the case that efforts to improve those schools’ test score value-added could jeopardize those other dimensions. Teachers don’t have all the time in the world.

Because of this (and more), I have no doubt that policies like No Child Left Behind have hurt people. Because so many schools that didn’t make Adequate Yearly Progress were closed, so many more had their leadership disrupted, and so many others simply had to deal with the onerous burdens that followed a failure to make AYP, I have no doubt that many among them were penalized despite providing plenty of value, and because test scores are so resistant to serious change, I have no doubt that the penalties often ran against teachers’ best efforts to teach to the test.

In some domains, testing is the best thing around. But that’s far from universal.

October 25, 2025 Update: A Newer Fadeout Meta-Analysis

I noted above that intervention effects on test scores tend to fade with time. A newer meta-analysis of the fadeout effect confirms the same: “intervention impacts on… skills demonstrated fadeout, especially for interventions that produced larger initial effects.” What makes this interesting is that the authors of that meta-analysis explicitly noted what I did above:

Although some educational programs produce life-altering benefits in the long-term, our review suggests that these long-term impacts are unlikely to be explained by fully persistent effects on targeted cognitive or social–emotional skills during childhood.

The result looks like this:

The authors found the impacts were, in aggregate, nonsignificant beyond a year or two. Of course, one has to be careful when aggregating across studies like this, but I don’t think we need to be worried about underestimating effects.

For one, when large, credible educational interventions with mandatory preregistration, reporting, and analysis by unaffiliated persons are conducted, effect sizes tend to be extremely marginal, and that’s immediately posttest. For two, the key signature of publication bias shows up in these results: larger studies returned smaller effects.

Given all of the prior literature on this subject—which shows that, where publication bias is impossible there is no such relationship—we can be reasonably confident that this is due to publication bias, although it is theoretically possible that the pattern shows up because smaller interventions are more intensive. A hint that it’s publication bias and not smaller interventions being more intensive was given when the authors looked at intensity as measured by the length of an intervention, finding no moderation (posttest d = 0.48 for <200-hour interventions and 0.50 for <100-hour interventions). Additionally, if the correlation between effect sizes and standard errors was due to intensity, then it should be unaffected adjusting for p-hacking to get right under significance thresholds. Using a selection model that adjusts for some of the impact of p-hacking right under a threshold, the authors found adjusted effect sizes were 40% smaller at posttest, 36% smaller at 6-12 months, and 32% smaller at 1-2 years (see Table S8). Recall that publication bias adjustments tend to still come with inflated effects compared to large preregistered replication studies, and it should be plenty clear that the estimates above are, if anything, optimistic.

With those qualifications out of the way, I think the authors’ point is still strong and worth reiterating in broader terms: the benefits of education and educational interventions go beyond test scores; if those are the only things we focus on, then we will be misled into subjecting people to poorer-quality educations because we have the wrong target.

In the cross-section, bias-induced gains might also have predictive power due to their facultative relationship with predictive group membership or a scoring criteria, like passing an examination or meeting a cutoff score for a job interview.

I am aware that value-added measures are frequently overestimates and that they have been used to overstate the causal impacts of schools and teachers on students’ life outcomes. The effects noted here are generally small but real.

I am aware of and have frequently spoken about the issues with these composites, but as the coverage of the Barbadian study shows, I will note when the composites look to be problematic.

The data from this study shows a further problem with estimates of value-added: they are not themselves stable:

The reason is not greater variation in the non-test score value-added dimensions.

It has also been documented that parental beliefs about returns to education differ meaningfully, perhaps explaining some of the ‘inefficiency.’

Price, location, ability to get kids to school, etc. are already details that credible studies effectively ‘factor in,’ so they don’t need to be mentioned.

I was constantly having to translate your prose into dumdum. Why say “value added “ when you can just say “better”? I realize this kind of critique for a totally free service is churlish, but the info is fascinating and important and could reach more people if the prose style was just a hair dopier.

Great post. In your opinion, what is the mechanism by which quality education improves outcomes? Why does this happen? Is it signaling, selection, or some kind of genuine human capital accumulation? If the latter, it would presumably be through the formation of non-cognitive skills.